Examining Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Ever Breastfed Children, NHANES 1999–2020

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Breastfeeding Health Benefits and Risk Reduction for Mothers and Infants

1.2. Ever Breastfed Rates in the United States

1.3. Sociodemographic Factors and Breastfeeding

2. Methods

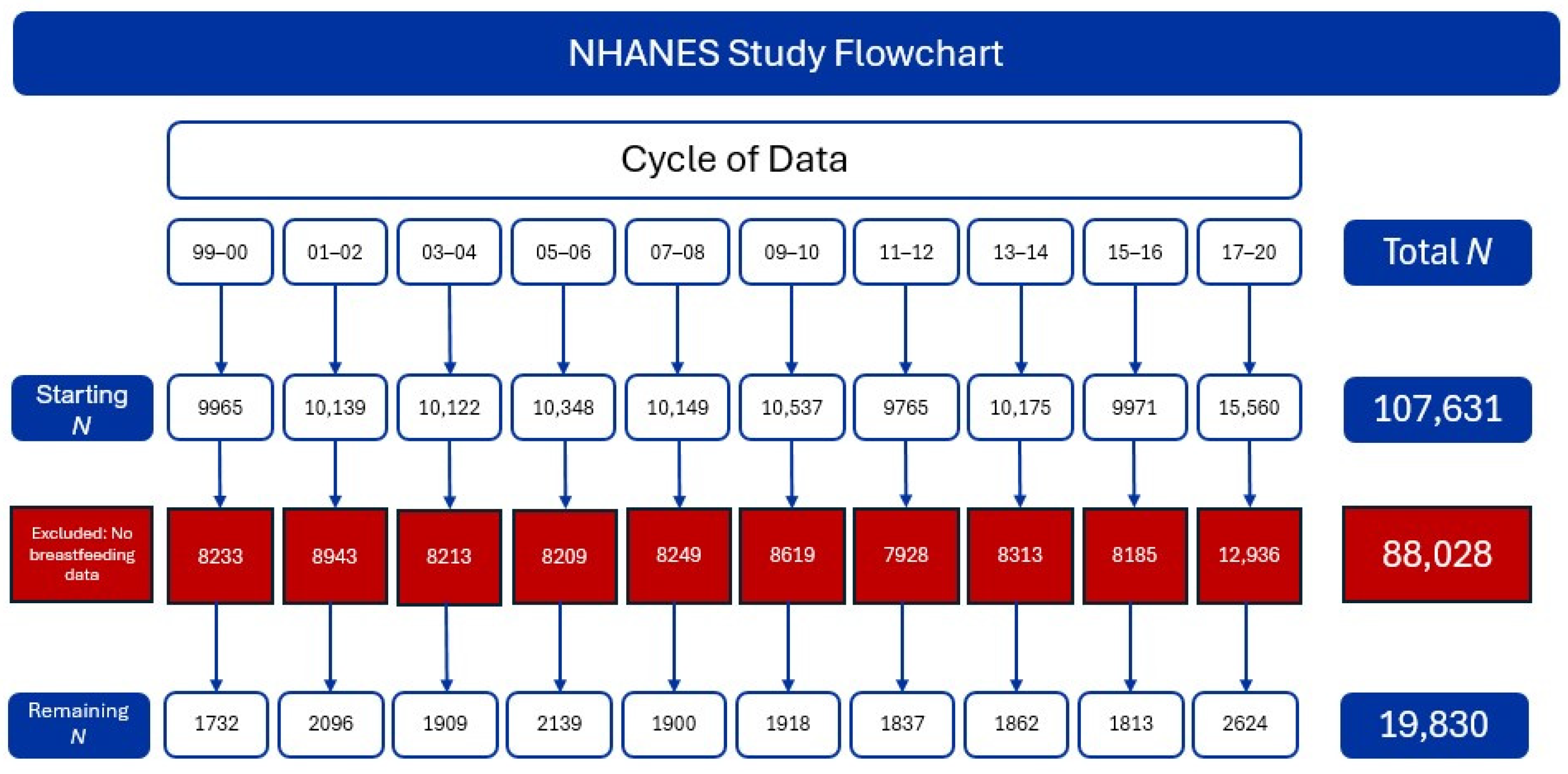

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Setting and Relevant Context

2.1.2. Sample

2.1.3. Measurement

2.1.4. Data Collection

2.1.5. Data Analysis

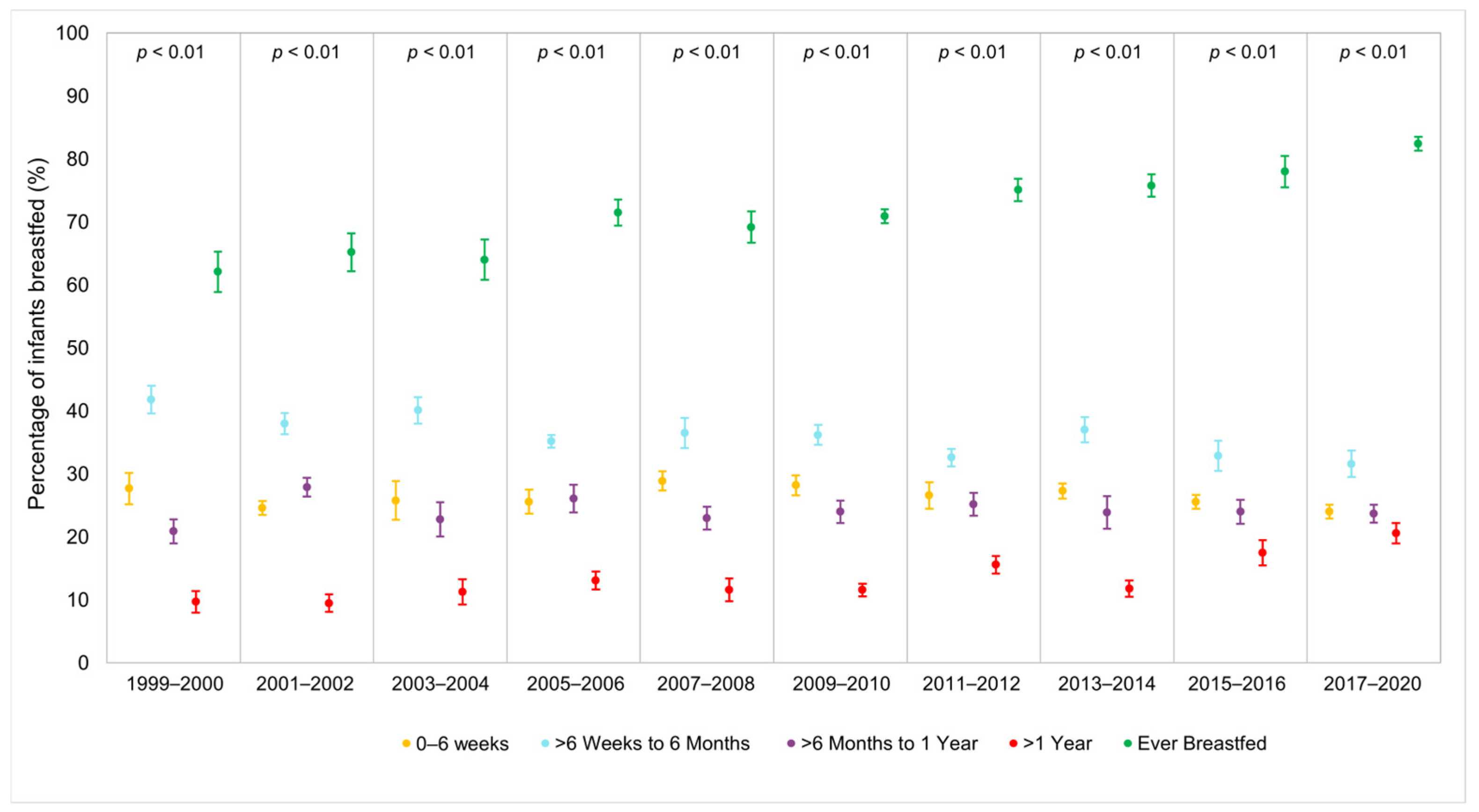

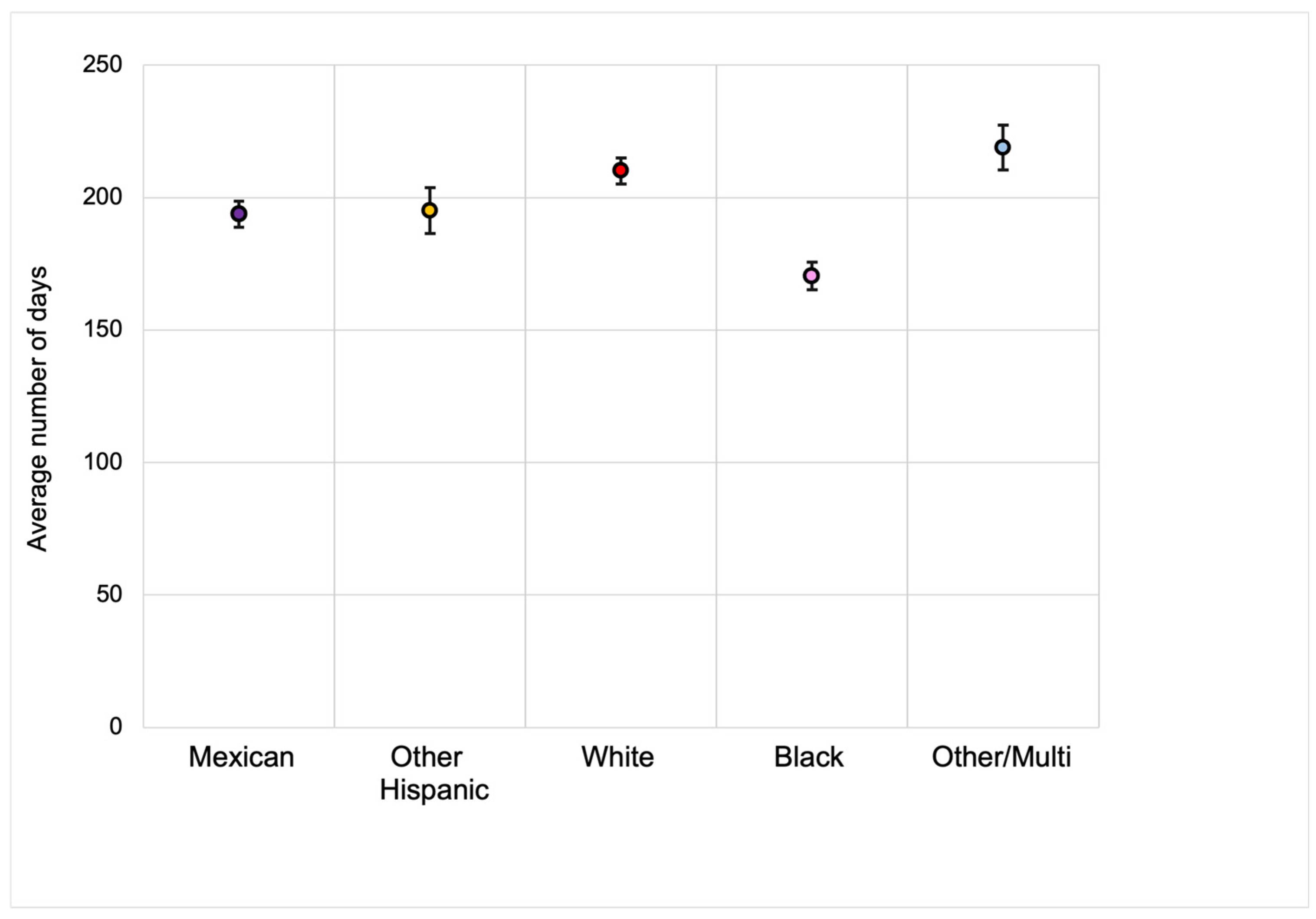

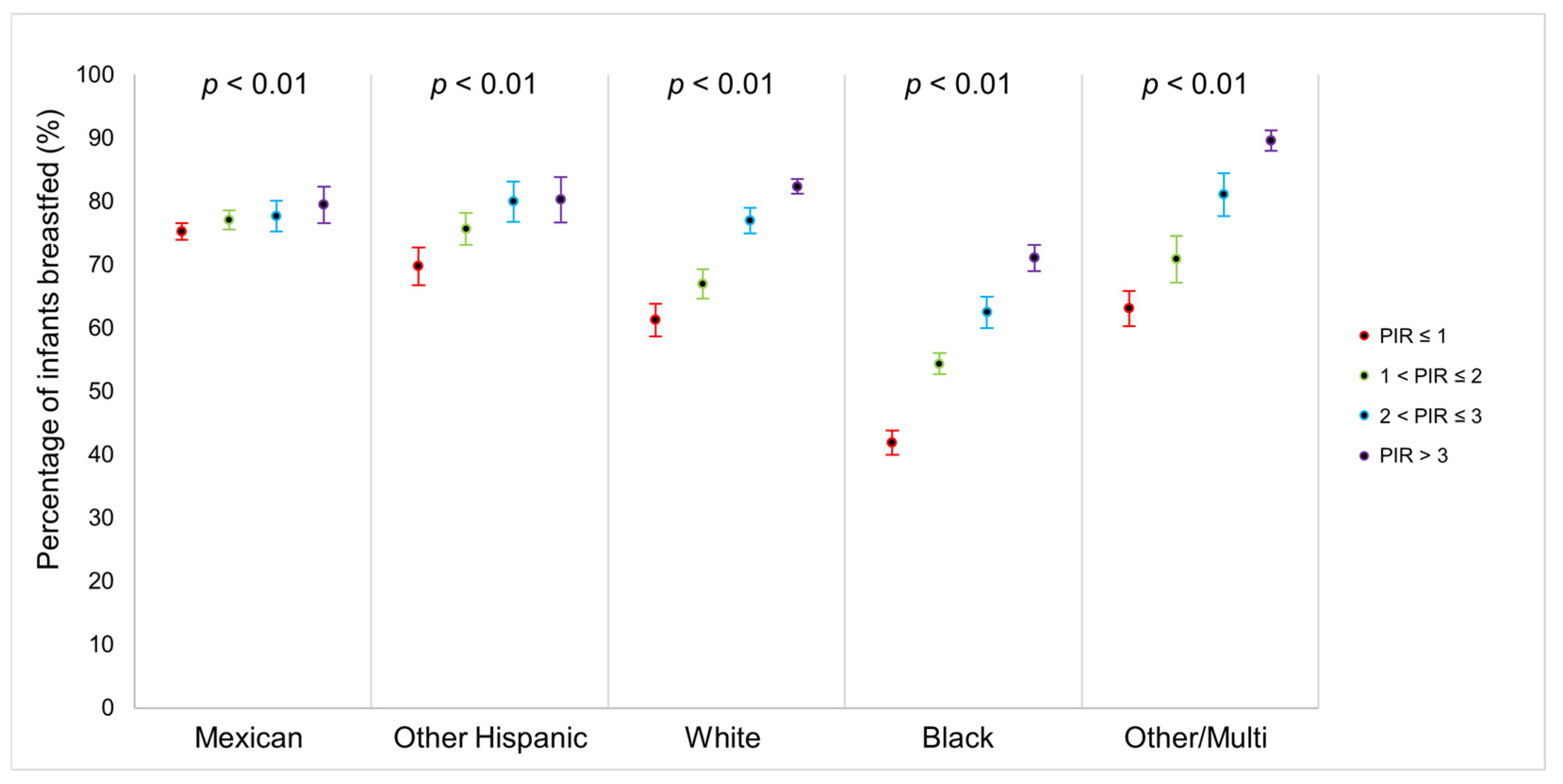

3. Results

Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shimizu, Y. Breastfeeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/Health-Topics/Breastfeeding#Tab=Tab_2 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Scott, J.; Ahwong, E.; Devenish, G.; Ha, D.; Do, L. Determinants of Continued Breastfeeding at 12 and 24 Months: Results of an Australian Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, N.F. Infant Feeding Matters. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Ware, J.; Chen, A.; Nelson, J.M.; Kmet, J.M.; Parks, S.E.; Morrow, A.L.; Chen, J.; Perrine, C.G. Breastfeeding and Post-Perinatal Infant Deaths in the United States, A National Prospective Cohort Analysis. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022, 5, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaniol, A.M.; Da Costa, T.H.M.; Bortolini, G.A.; Gubert, M.B. Breastfeeding Reduces Ultra-Processed Foods and Sweetened Beverages Consumption Among Children Under Two Years Old. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.S.; Grassley, J.S. African American Women And Breastfeeding: An Integrative Literature Review. Health Care Women Int. 2013, 34, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Benefits Both Baby and Mom. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/Breastfeeding/Features/Breastfeeding-Benefits.Html (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Quesada, J.A.; Méndez, I.; Martín-Gil, R. The Economic Benefits of Increasing Breastfeeding Rates in Spain. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nis-Child Data Results. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/Breastfeeding-Data/Survey/Results.Html (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Healthy People 2030. Increase The Proportion of Infants Who Are Breastfed Exclusively Through Age 6 Months—Mich-15. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/Healthypeople/Objectives-And-Data/Browse-Objectives/Infants/Increase-Proportion-Infants-Who-Are-Breastfed-Exclusively-Through-Age-6-Months-Mich-15 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Marks, K.J.; Nakayama, J.Y.; Chiang, K.V.; Grap, M.E.; Anstey, E.H.; Boundy, E.O.; Hamner, H.C.; Li, R. Disaggregation of Breastfeeding Initiation Rates by Race and Ethnicity-United States, 2020–2021. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, E114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.V.; Li, R.; Anstey, E.H.; Perrine, C.G. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Breastfeeding Initiation─United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, J.L.; Hamner, H.C.; Chen, J.; Avila-Rodriguez, W.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Perrine, C.G. Racial Disparities in Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration Among U.S. Infants Born in 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, J.; Echeverria, S.E.; Armah, S.M.; Dharod, J.M. Household Food Insecurity, Breastfeeding, and Related Feeding Practices in Us Infants and Toddlers: Results from Nhanes 2009–2014. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.E.; Li, X.; Adams-Huet, B.; Sandon, L. Infant Feeding Practices and Dietary Consumption of Us Infants and Toddlers: National Health AND Nutrition Examination Survey (Nhanes) 2003–2012. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odar Stough, C.; Khalsa, A.S.; Nabors, L.A.; Merianos, A.L.; Peugh, J. Predictors of Exclusive Breastfeeding for 6 Months in A National Sample of Us Children. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, M.V.; Diaz, V.A.; Mainous, A.G., 3rd; Geesey, M.E. Prevalence of Breastfeeding and Acculturation in Hispanics: Results from Nhanes 1999–2000 Study. Birth 2005, 32, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, A.; Spatz, D.L.; Jefferson, U.T.; Lucas, R.; O’neill, B.; Henderson, W.A. Breastfeeding Social Support Among African American Women in the United States: A Meta-Ethnography. Adv. Neonatal Care 2023, 23, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wunderlich, S.M.; Fly, A.D. Predicting Intentions to Continue Exclusive Breastfeeding For 6 Months: A Comparison Among Racial/Ethnic Groups. Matern. Child. Health J. 2011, 15, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Perrine, C.G.; Anstey, E.H.; Chen, J.; Macgowan, C.A.; Elam-Evans, L.D. Breastfeeding Trends by Race/Ethnicity Among Us Children Born from 2009 to 2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, E193319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleszar, L.G.; Bryant, A.S.; Johnson, C.O.; Blacker, B.F.; Aravkin, A.; Baumann, M.; Dwyer-Lindgren, L.; Kelly, Y.O.; Maass, K.; Zheng, P.; et al. Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States. JAMA 2023, 330, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria, K.; Fleszar-Pavlović, S.; Hua, J.; Ramirez Loyola, M.; Reuschel, H.; Song, A.V. How Socioeconomic Status and Acculturation Relate to Dietary Behaviors Within Latino Populations. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckinney, C.O.; Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Chase-Lansdale, P.L.; Ramey, S.L.; Krohn, J.; Reed-Vance, M.; Raju, T.N.; Shalowitz, M.U. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20152388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiodu, I.V.; Bugg, K.; Palmquist, A.E.L. Achieving Breastfeeding Equity and Justice in Black Communities: Past, Present, and Future. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/Nhanescitation.Aspx (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2012, 129, E827–E841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shargorodsky, J.; Curhan, S.G.; Curhan, G.C.; Eavey, R. Change in Prevalence of Hearing Loss in Us Adolescents. JAMA 2010, 304, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, S.S.; Dow-Fleisner, S.; Noble, A. Breastfeeding and the Affordable Care Act. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 62, 1071–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, M.A.; Hamulka, J. Reasons for Non-Exclusive Breast-Feeding in the First 6 Months. Pediatr. Int. 2018, 60, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, E.J. Breastfeeding and Postpartum Depression: A Review of Relationships and Potential Mechanisms. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P. Management of Mastitis in Breastfeeding Women. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 78, 727–731. [Google Scholar]

- Green, V.L.; Killings, N.L.; Clare, C.A. The Historical, Psychosocial, and Cultural Context of Breastfeeding in the African American Community. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramling, J. The African American Breastfeeding Alliance of Dane County Celebrates 20 Years of Service: Fighting an Uphill Battle for Healthy Babies. Available online: https://www.capitalcityhues.com/02052024aaba1/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Black Mamas Matter Alliance Inc. (BMMA). Black Mamas Matter Alliance Collective Statement on the Infant Formula Shortage. 2022. Available online: https://blackmamasmatter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Infant-Formula-Press-Statement-2.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Dogan, J.; Hargons, C.; Stevens-Watkins, D. “Don’t Feel Like You Have to Do This All on Your Own”: Exploring Perceived Partner Support of Breastfeeding Among Black Women in Kentucky. J. Hum. Lact. 2023, 39, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, C.O.; Gross, T.T.; Story, C.R.; McElderry, C.G.; Stone, K.W. Social Media Usage as a Form of Breastfeeding Support Among Black Mothers: A Scoping Review of the Literature. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2023, 68, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubitt, J.; Hodges, A.; Galiwango, G.; Van Lierde, K. Malnutrition in Cleft Lip and Palate Children in Uganda. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2012, 35, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, G.T. Galactosemia: When Is It a Newborn Screening Emergency? Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 106, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radke, S.M. Common Complications of Breastfeeding and Lactation: An Overview for Clinicians. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 65, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, M.D.; Ro, A.; Palma, A. Work, Race and Breastfeeding Outcomes for Mothers in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, E0251125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrine, C.G.; Chiang, K.V.; Anstey, E.H.; Grossniklaus, D.A.; Boundy, E.O.; Sauber-Schatz, E.K.; Nelson, J.M. Implementation of Hospital Practices Supportive of Breastfeeding in the Context of Covid-19-United States, July 15-August 20, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1767–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Patel, S. The Effectiveness of Lactation Consultants and Lactation Counselors on Breastfeeding Outcomes. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, E.C.; Damio, G.; Laplant, H.W.; Trymbulak, W.; Crummett, C.; Surprenant, R.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Promoting Equity in Breastfeeding Through Peer Counseling: The Us Breastfeeding Heritage and Pride Program. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinour, L.M.; Bai, Y.K. Breastfeeding: The Illusion of Choice. Womens Health Issues 2016, 26, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ever Breastfed (N = 13,762) | Never Breastfed (N = 6068) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presented as N (Weighted %) or Mean (SD) | |||

| Child sex at birth (n = 19,830) | |||

| Female | 6754 (48.6) | 2953 (48.9) | 0.5233 |

| Male | 7008 (51.4) | 3115 (51.1) | |

| Child Race/Ethnicity (n = 19,830) | |||

| Mexican | 4053 (16.7) | 1244 (13.1) | <0.0001 |

| Other Hispanic | 1364 (8.6) | 449 (7.2) | |

| NHW | 4395 (55.4) | 1644 (49.5) | |

| NHB | 2435 (9.9) | 2278 (23.4) | |

| Other or Multiracial | 1515 (9.4) | 453 (6.8) | |

| Child Birth Weight (n = 19,624) | 7.34 ± 0.02 | 7.05 ± 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Length of Time Breastfed (n = 13,505) | |||

| 0–6 Weeks | 4387 (25.9) | – | – |

| >6 Weeks to 6 Months | 4885 (35.2) | – | – |

| >6 Months to 1 Year | 2773 (23.9) | – | – |

| >1 Year | 1460 (13.8) | – | |

| Missing | 257 (1.3) | – | |

| Mother’s Age When Born (n = 19,758) | 28.4 ± 0.11 | 26.0 ± 0.15 | <0.0001 |

| Mother Smoked While Pregnant (n = 19,768) | |||

| Yes | 1161 (9.2) | 1266 (23.6) | <0.0001 |

| No | 12,581 (90.7) | 4760 (75.4) | |

| Missing | 20 (0.1) | 42 (1.0) | |

| Mother’s US Citizenship (n = 17,195) | |||

| Yes | 11,430 (81.7) | 5474 (90.2) | <0.0001 |

| No | 257 (1.5) | 34 (0.5) | |

| Missing | 2075 (16.8) | 560 (9.3) | |

| Family Income to Poverty Ratio (n = 18,137) | 2.52 ± 0.04 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | <0.0001 |

| Mother’s Insurance Coverage (n = 19,714) | |||

| Yes | 12,453 (92.0) | 5542 (91.4) | 0.11 |

| No | 1240 (7.5) | 479 (7.6) | |

| Missing | 69 (0.51) | 47 (0.97) | |

| Household Food Security (n = 19,265) | |||

| Full Food Security | 8225 (68.3) | 3332 (61.4) | <0.0001 |

| Marginal Food Security | 1885 (11.1) | 961 (13.2) | |

| Low Food Security | 2390 (12.8) | 1134 (16.0) | |

| Very Low Food Security | 870 (4.8) | 468 (6.4) | |

| Missing | 392 (3.0) | 173 (3.0) | |

| Mother’s General Health Condition (n = 19,828) | |||

| Excellent | 7779 (60.0) | 3142 (52.0) | <0.0001 |

| Very Good | 3195 (23.4) | 1431 (25.1) | |

| Good | 2290 (13.7) | 1203 (18.5) | |

| Fair | 470 (2.7) | 258 (3.8) | |

| Poor | 27 (0.2) | 33 (0.6) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | |

| Mother Seen Mental Health Professional in Past Year (n = 6571) | |||

| Yes | 169 (1.7) | 119 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| No | 4142 (39.9) | 2141 (44.0) | |

| Missing | 9451 (58.4) | 3808 (53.3) | |

| No. Breastfed (Weighted %) | Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race-Ethnicity | |||||

| NHW | 4395 (74.3) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| NHB | 2435 (52.3) | 0.80 (0.79–0.82) | 0.84 (0.82–0.85) | 0.87 (0.85–0.88) | 0.84 (0.82–0.86) |

| Mexican | 4053 (76.6) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | 1.10 (1.08–1.12) | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) |

| Other Hispanic | 1364 (75.3) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) |

| Other/Multi | 1515 (78.1) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) |

| Mother’s Age at Birth | |||||

| 20 and under | 1888 (55.0) | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | 0.80 (0.77–0.82) | 0.84 (0.81–0.86) | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) |

| 21–25 | 3453 (65.9) | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) | 0.88 (0.86–0.90) | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) |

| 26–30 | 3892 (77.5) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

| 31–35 | 3005 (79.7) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| 36 and older | 1510 (79.2) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) |

| Poverty-to-Income Ratio | |||||

| <1 | 4217 (61.5) | 0.81 (0.80–0.83) | – | 0.86 (0.84–0.88) | 0.88 (0.86–0.91) |

| 1–2 | 3287 (68.2) | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) | – | 0.90 (0.88–0.92) | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) |

| 2–3 | 1734 (76.0) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | – | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) |

| 3+ | 3349 (61.5) | 1.00 (Referent) | – | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Mother’s Insurance Coverage | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | ||||

| Yes | 12,453 (72.2) | 1.00 (Referent) | – | – | 1.00 (Referent) |

| No | 1240 (71.7) | 0.99 (0.97–1.03) | – | – | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) |

| Mother’s US Citizenship | |||||

| US Citizenship | 11,430 (70.0) | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) | – | – | 0.86 (0.81–0.91) |

| Non-US Citizenship | 257 (87.7) | 1.00 (Referent) | – | – | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Food Security | |||||

| Full | 8225 (74.1) | 1.00 (Referent) | – | – | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Marginal | 1885 (68.3) | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | – | – | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) |

| Low | 2390 (67.4) | 0.93 (0.91–0.96) | – | – | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) |

| Very Low | 870 (65.7) | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | – | – | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) |

| Mother Smoked While Pregnant | |||||

| No | 12,581 (75.6) | 1.00 (Referent) | – | – | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Yes | 1161 (50.2) | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | – | – | 0.82 (0.79–0.84) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amezcua, J.; West, L.M.; Malkami, C.; Vernon, M.; Pollard, E.; Moore, J.X. Examining Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Ever Breastfed Children, NHANES 1999–2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030428

Amezcua J, West LM, Malkami C, Vernon M, Pollard E, Moore JX. Examining Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Ever Breastfed Children, NHANES 1999–2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):428. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030428

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmezcua, Jessica, Lindsey M. West, Camelia Malkami, Marlo Vernon, Elinita Pollard, and Justin X. Moore. 2025. "Examining Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Ever Breastfed Children, NHANES 1999–2020" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030428

APA StyleAmezcua, J., West, L. M., Malkami, C., Vernon, M., Pollard, E., & Moore, J. X. (2025). Examining Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Ever Breastfed Children, NHANES 1999–2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030428