The Beneficial Interaction Between Human Well-Being and Natural Healthy Ecosystems: An Integrative Narrative Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

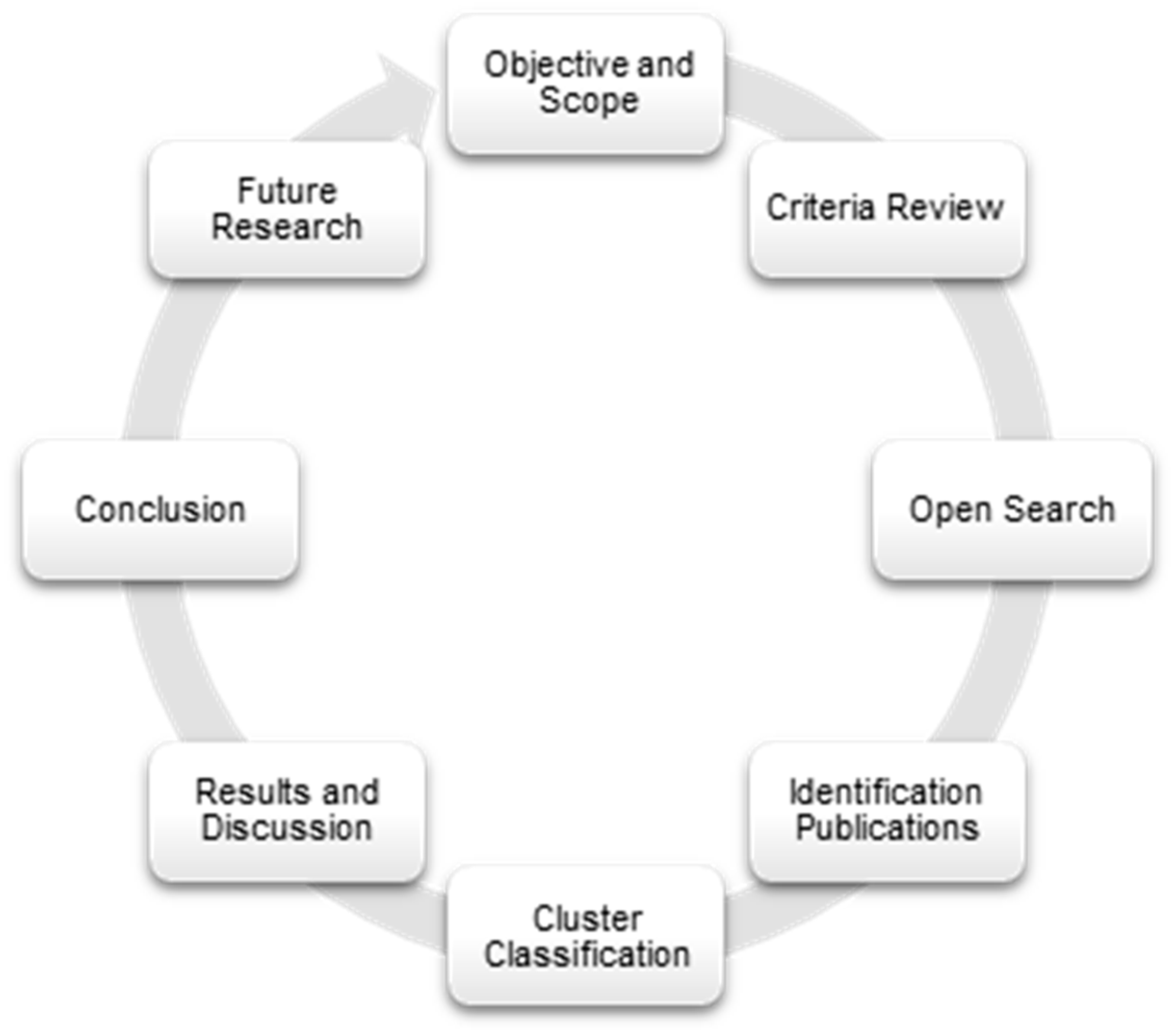

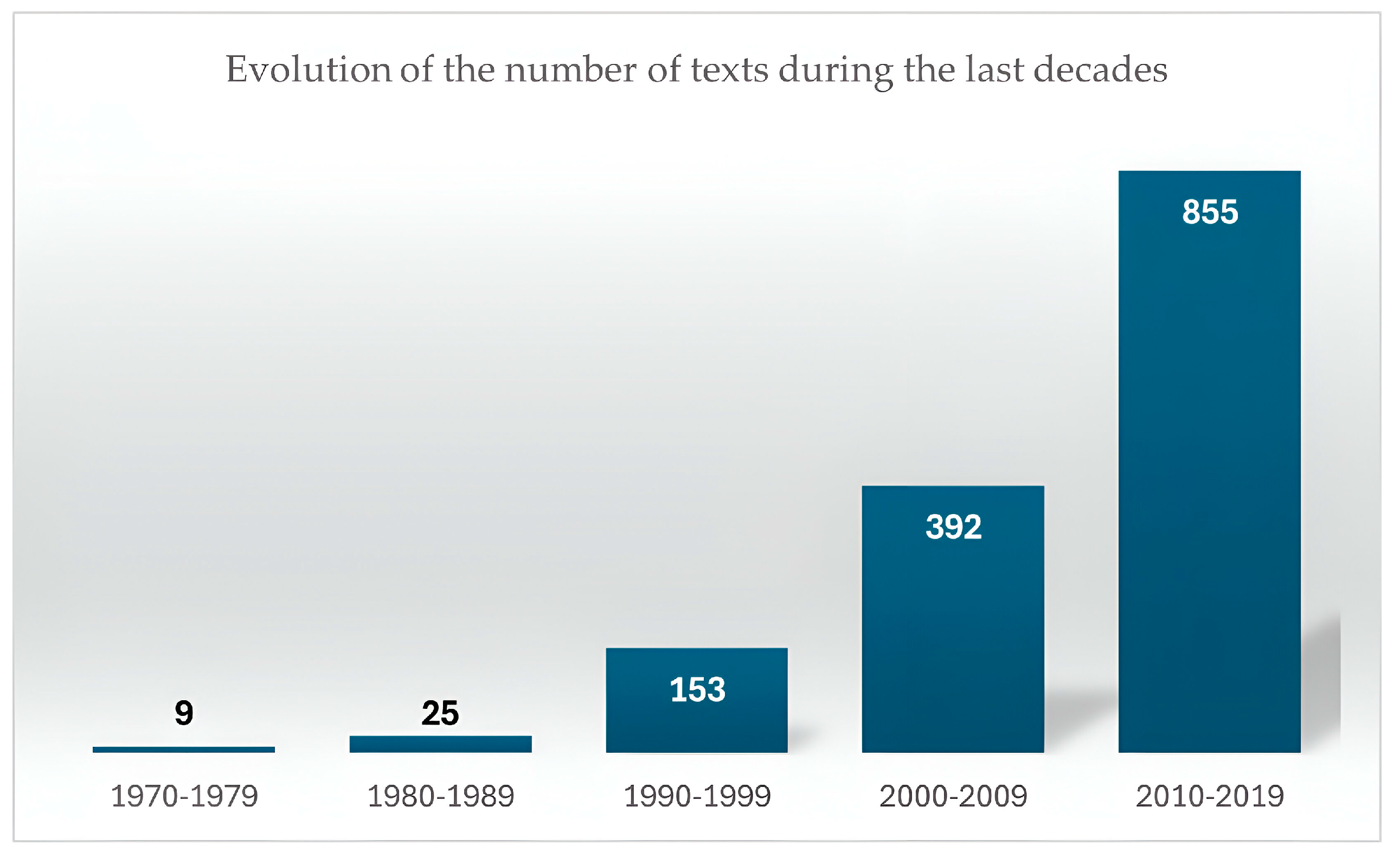

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Criteria Review

2.2. Open Search

2.3. Identification of Relevant Publications

2.4. Cluster Classification

- ❖

- The benefits of nature;

- ❖

- The attitude toward nature;

- ❖

- The states of mind;

- ❖

- The sociodemographic aspects;

- ❖

- The methods used.

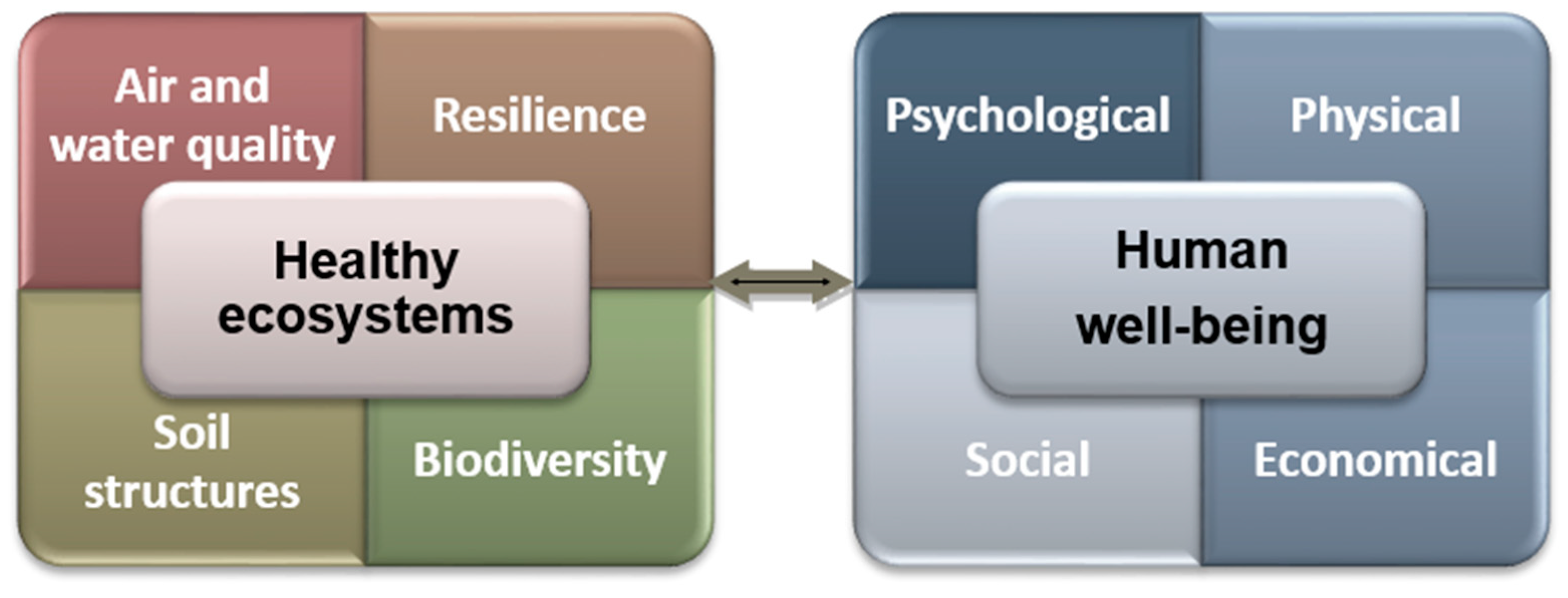

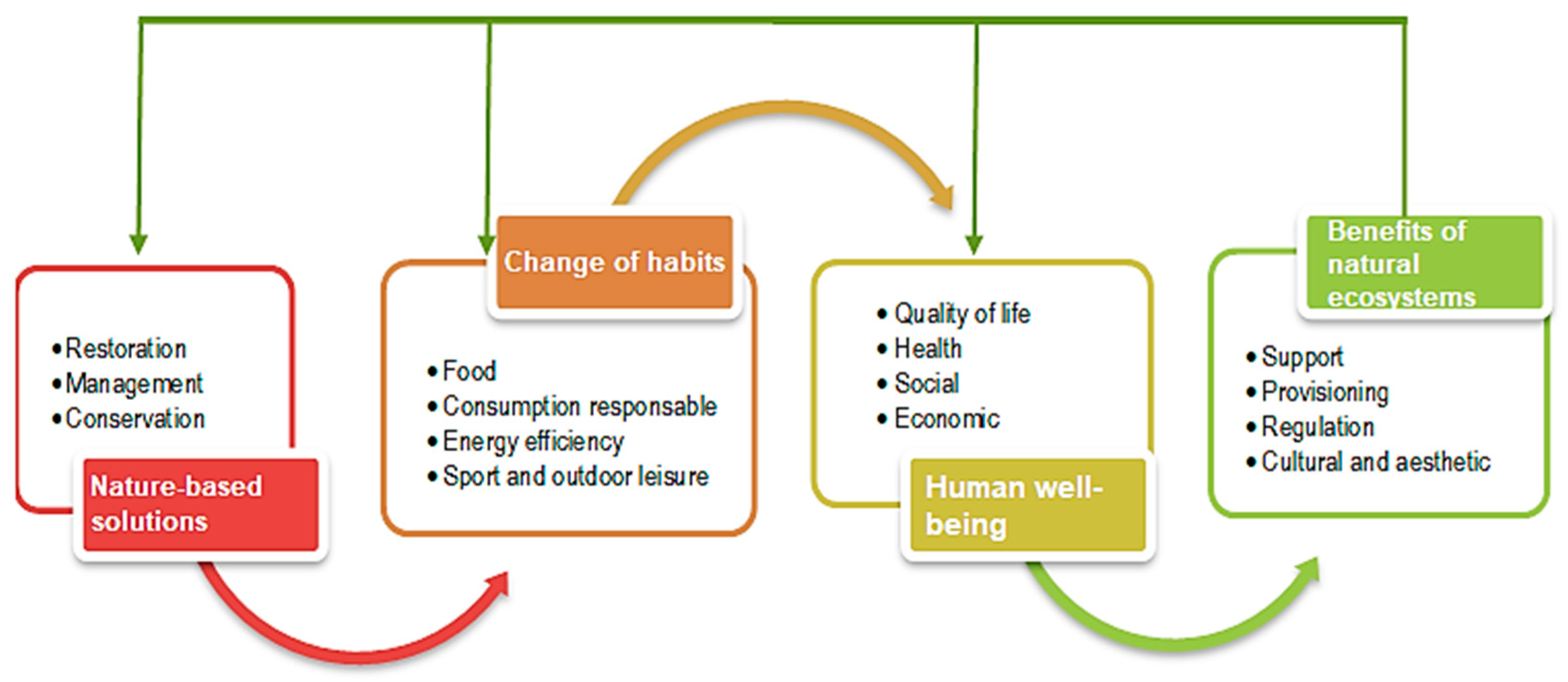

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. From the Point of View of the Assessment of the Benefits of Nature

- Promotes self-esteem, autonomy, and a sense of responsibility [31];

- Favors reflection, concentration, and emotional intelligence [32];

- Is a source of stimulation for creativity [33];

- Influences positive emotions and emotional balance [34];

- Aids recovery from emotional fatigue, depression, states of anxiety, and stress [35];

- Restores attention [36].

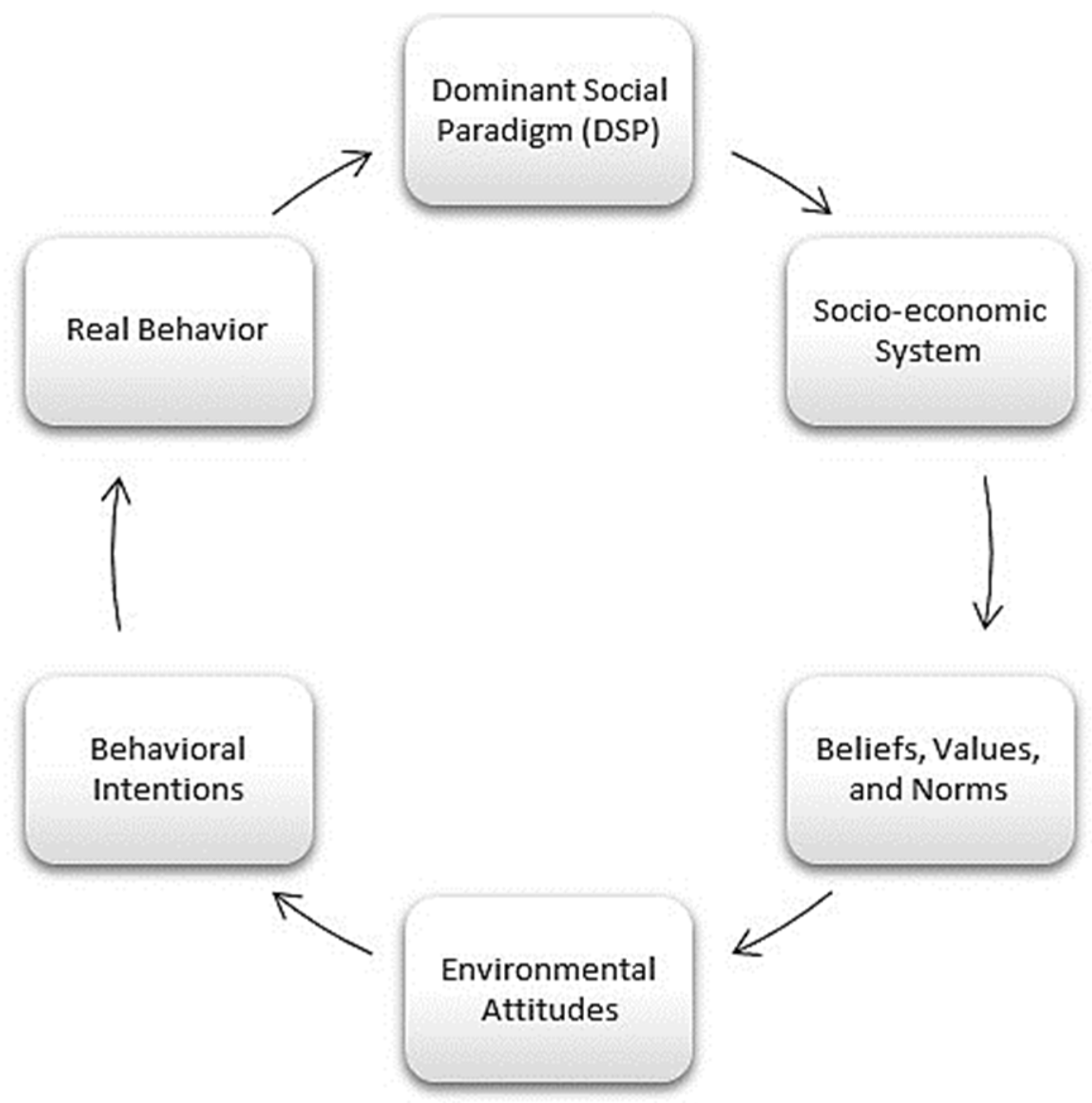

3.2. From the Point of View of Man’s Attitude Toward Nature

- The despot: We manage nature for our own enjoyment;

- Enlightened ruler: We are guides and we collaborate with it;

- Nature’s steward: We care for nature, which belongs to its Creator;

- Partners with nature: We have equal conditions with it;

- Participants in nature: We are part of it;

- The mystic union between us and nature as one.

- Ecocentrism is the belief in the intrinsic importance of nature, which is positively correlated with nature conservation and environmental organizations and negatively related with environmental apathy; this represents the most advanced level of environmental concern and the highest level of moral reasoning. It is positively related with Kohlberg’s moral principle based on the concepts of justice, equity, rights, and obligations [79]. It is associated with the value–basis theory of environmental attitudes and the new ecological paradigm (NEP) [80] and negatively associated with the values of power and tradition [81];

- Knowledge and environmental awareness;

- Social and personal norms;

- Incentives associated with environmental actions;

- Legislation and economic costs;

- Personal values.

3.3. From the Point of View of States of Mind

3.4. From a Sociodemographic Point of View

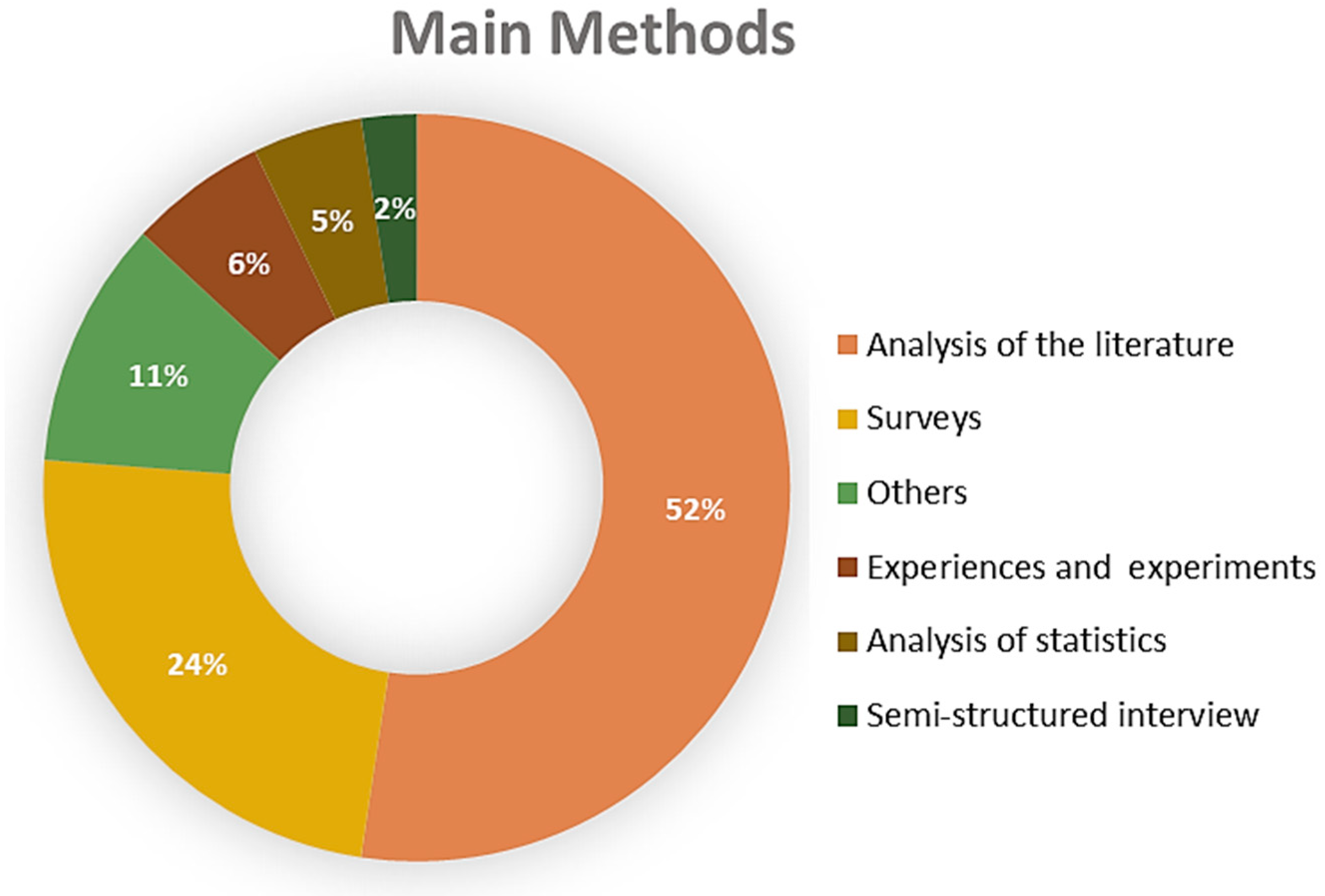

3.5. From the Point of View of the Assessment of the Methods Used

3.6. Results with COVID-19

3.7. The Main Gaps

- There is a paucity of research examining the integration of individual nature-related factors such as connection to nature and time spent in nature. Furthermore, studies often fail to take into account the manner in which these elements interact to influence well-being [143];

- We need to better understand how human–nature relationships, such as cultural ecosystem services, contribute to well-being. Future research must focus on identifying the mechanisms that make people aware of the natural environment and connect them to it [144];

- New research is needed into how the restorative physiological mechanisms of natural environments are impacted by socio-economic factors. The effects of nature on mental health in diverse populations, including clinical groups, ethnically diverse communities, and low- and middle-income countries, have not been researched enough to date [133];

- Further research is required on the relationship between a connection with nature, well-being, pro-environmental behaviors, and life satisfaction. The mechanisms through which nature influences well-being and behaviors are not yet fully elucidated. Further research is necessary to clarify these pathways [96,145];

- There is a need for more robust, long-term studies to compare the effectiveness of NbS with non-NbS alternatives. The current literature shows biases towards urban environments and lacks comprehensive studies on the full range of well-being benefits from NbS [146];

- In order to establish a connection between environmental knowledge and awareness, it is crucial to consider proximity to the natural environment and availability of accessibly located resources for the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors. There is a need to integrate various theories to better understand the complex interplay factors [147];

- More research is required for the development of methodological tools, more sophisticated models, and frameworks that incorporate complex dynamics, social–cultural dimensions, and diverse environmental contexts. Causal inference methods and integrating quantitative and qualitative methods must be improved to enhance the effectiveness of strategies for managing human–environment interactions and promoting sustainability [148].

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gould, R.K.; Merrylees, E.; Hackenburg, D.; Marquina, T. “My place in the grand scheme of things”: Perspective from nature and sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 1755–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; White, M.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. El papel de la naturaleza en el cambio climático. Nat. Y Biodivers. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, C.M.L.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.J.; Krettenauer, T. Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behaviour from Early Adolescence to Adulthood: A Comparison of Urban and Rural Canada. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.J.; Gibson, R.B. A Novel Framework for Inner-Outer Sustainability Assessment. Challenges 2022, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgorn, E.; Ullerup, H. Invoking ‘Empathy for the Planet’through participatory ecological storytelling: From human-centered to planet-centered design. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, L.S.; Scheuermann, A.; Prestele, E.; Reese, G. Cultivating connectedness: Effects of an app-based compassion meditation course on changes in global identity, nature connectedness, and pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, J.; Warber, S.; Robinson, J.M.; Logan, A.C.; Prescott, S.L. Nature Connection: Providing a Pathway from Personal to Planetary Health. Challenges 2023, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. Impact of the Natural Environment on Individuals’ Psychological Well-being. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 26, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buceta-Albillos, N.; Ayuga-Téllez, E. The State of the Art in the Biophilic Construction of Healthy Spaces for People. Buildings 2024, 14, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Hernández, L.F.; Sotelo-Castillo, M.A.; Echeverría-Castro, S.B.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.O. Connectedness to nature: Its impact on sustainable behaviors and happiness in children. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voltmer, K.; von Salisch, M. Promoting Subjective Well-Being and a Sustainable Lifestyle in Children and Youth by Strengthening Their Personal Psychological Resources. Sustainability 2024, 16, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A. Adaptación al cambio climático basada en ecosistemas. In Cambio Climático en un Paisaje Vivo: Vulnerabilidad y Adaptación en la Cordillera Real Oriental de Colombia, Ecuador y Perú; Naranjo, G., Ed.; WWF—Fundación Natura: Cali, Colombia, 2010; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- King, S.; Kostewicz, D.; Enders, O.; Burch, T.; Chitiyo, A.; Taylor, J.; DeMaria, S.; Reid, M. Search and Selection Procedures of Literature Reviews in Behavior Analysis. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 2020, 43, 725–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theile, C.; Beall, A. Narrative Reviews of the Literature: An overview. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 98, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Legese, G. Ecosystem services research in mountainous regions: A systematic literature review on current knowledge and research gaps. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wei, H.; Dong, X.; Wang, X.-C.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Y. Integrating Land Use, Ecosystem Service, and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A.; Da Cunha Pinto, J.; De Castro Medeiros, L. Recognizing Patterns of Nature Contact Associated with Well-Being: An Exploratory Cluster Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Mundial del Medio Ambiente. Nuestro Futuro Común; Ed. Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. A Guide to the Healthy Parks Healthy People. Approach and Current Practices; IUCN World Parks Congress: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumann, K.; Gärling, T.; Stormark, K.M. Selective attention and heart rate responses to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamosiunas, A.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Luksiene, D.; Dedele, A.; Reklaitiene, R.; Baceviciene, M.; Vencloviene, J.; Bernotiene, G.; Radisauskas, R.; Malinauskiene, V.; et al. Accessibility and use of urban green spaces, and cardiovascular health: Findings from a Kaunas cohort study. Environ. Health 2014, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Li, Q.; Kagawa, T.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Effects of viewing forest landscape on middle-aged hypertensive men. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 21, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollick, M.F. Vitamine D: Important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseas-es, and some cancers. South. Med. Assoc. 2005, 98, 1024–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Effets des Forêts et des Bains de Forêt (Shinrin-Yoku) Sur la Santé Humaine: Une Revue de la Littérature; S.F.S.P. Santé Publique: Laxou, France, 2019; pp. 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, N.M.; Lekies, K.S. Nature and the life course: Pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism. Child. Youth Environ. 2006, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: The role of mindfulness in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, D. Beyond Ecophobia: Reclaiming the Heart in Nature Education; The Orion Society and the Myrin Institute: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hueso, K.; Camina, E. La educación temprana en la naturaleza: Una inversión en calidad de vida, sostenibilidad y salud. In Boletín Carpeta Informativa 2015; CENEAM: Valsaín (Segovia), Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. Happiness is in our nature: Exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, F.; Palma-Oliveira, J.M. Urban neighbourhoods and intergroup relations: The importance of place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xiao, Y.; Van Koppen, C.; Ouyang, Z. Local perceptions of ecosystem services and protection of culturally protected forests in southeast China. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2018, 4, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutton, O.T.; Townsend, N.; Rutter, H.; Foster, C. Green space and physical activity: An observational study using the Health Survey for England data. Health Place 2012, 18, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, Q.; Craig, W.; Janssen, I.; Pickett, W. Exposure to public natural space as a protective factor for emotional well-being among young people in Canada. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J.S.; Kremers, S.P.; Droomers, M.; Hoefnagels, C.; Stronks, K.; Hosman, C.; de Vries, S. The impact of greenery on physical activity and mental health of adolescent and adult residents of deprived neighborhoods: A longitudinal study. Health Place 2016, 40, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.A.; Flouri, E.; Kokosi, T. The role of the physical environment in adolescent mental health. Health Place 2019, 58, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury-Bahi, G.; Galharret, J.M.; Lemée, C.; Wittenberg, I.; Olivos, P.; Loureiro, A.; Jeuken, Y.; Laïlle, P.; Navarro, O. Nature and well-being in seven European cities: The moderating effect of connectedness to nature. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2023, 15, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.; Reyers, B. Disentangling the complexity of human–nature interactions. People Nat. 2024, 6, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ecosistemas y Bienestar Humano: Síntesis Sobre Salud; Un informe de la Evaluación de los Ecosistemas del Milenio (EM): Ginebra, Suiza, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- López Vega, A. Gregorio Marañón, radiografía de un liberal; Ed. Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Louv, R. The Nature Principle: Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2012; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, V. Nature, self, and gender: Feminism, environmental philosophy, and the critique of rationalism. Hypatia 1991, 6, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailwood, S. Alienations and natures. Environ. Politics 2012, 21, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K. Extinction of experience: The loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Bioscience: Washington, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tidball, K.G. Urgent biophilia: Human-nature interactions and biological attractions in disaster resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, J.M.; Dopko, R.L.; Capaldi, C.A. Cooperation is in our nature: Nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiero, G.; Berto, R. From biophilia to naturalist intelligence passing through perceived restorativeness and connection to nature. Ann. Rev. Res. 2018, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) Defined by IUCN. 2018. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/our-work/nature-based-solutions (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S.; Walters, G. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscha, M.; Sangc, O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health—A systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Lee, K.; O’Riordan, T. The importance of an integrating framework for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: The example of health and well-being. BMJ Glob. Health 2016, 1, e000068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotsa, D.; Lilli, A.; Lilli, M.; Nikolaidis, N. On the impact of nature-based solutions on citizens’ health & well being. Energy Build. 2020, 229, 110527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welden, E.; Chausson, A.; Melanidis, M. Leveraging Nature-based Solutions for transformation: Reconnecting people and nature. People Nat. 2021, 3, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L., Jr. The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. Science 1967, 155, 1203–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. THE 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SGD). Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- FOREST EUROPE. Human Health and Sustainable Forest Management. Policy Recommendations of the Forest Europe; Expert Group on Human Health and Well-Being: Zvolen, Slovak Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment; Clayton, S., Opotow, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Corraliza, J.A.; Bethelmy, L. Vinculación a la naturaleza y orientación por la sostenibilidad. Rev. De Psicol. Soc. 2011, 26, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, E.A. Towards ecological self: Deep ecology meets constructionist self-theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Howell, R.T.; Iyerc, R. Engagement with natural beauty moderates the positive relation between connectedness with nature and psychological well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, P.S.; Fogarty, M.J.; Murawski, S.A.; Fluharty, D. Integrated Ecosystem Assessments: Developing the Scientific Basis for Ecosystem-Based Management of the Ocean. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslow, S.J.; Allen, M.; Holstein, D.; Sojka, B.; Barnea, R.; Basurto, X.; Carothers, C.; Charnley, S.; Coulthard, S.; Dolšak, N.; et al. Evaluating indicators of human well-being for ecosystem based Management. J. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2017, 3, 1411767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; CE; FAO; FMI. System of Environmental Economic Accounting. 2014. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/767283?v=pdf&ln=ar (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Diessner, R.; Solom, R.D.; Frost, N.K.; Parsons, L.; Davidson, J. Engagement with beauty: Appreciating natural, artistic, and moral beauty. J. Psychol. 2008, 142, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweers, W. Participating with Nature: Outline for an Ecologization of Our World View; International Books, Cop.: Oakland, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. Ecology, Community, and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S.C.; Barton, M. Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1994, 14, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. The Philosophy of Moral Development: Moral Stages and the Idea of Justice; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. The New Ecological Paradigm in social-psychological context. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L. Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: Evidence for consistency across 14 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P.; Lee, S.L.; Chao, M.M. Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism enhances connectedness to and protectiveness toward nature. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Morewedge, C.K.; Epley, N.; Monteleone, G.; Gao, J.-H.; Cacioppo, J.T. Making sense by making sentient: Effectance motivation increases anthropomorphism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 410–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crutzen, P.J. Geology of mankind: The Anthropocene. Nature 2002, 415, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiak, C.P.; Baril, G.L. Moral reasoning and concern for the environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K. The new environmental paradigm: A proposed measuring instrument and preliminary results. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirages, D.; Ehrlich, P. Ark II: Social Response to Environmental Imperatives; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, W.; Beckmann, S. Rationality and the reconciliation of the DSP with the NEP. In Environmental Regulation and Rationality: Multidisciplinary Perspectives; Beckmann, S., Madsen, E., Eds.; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus, Denmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, W. Dominant Social Paradigm. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.; Brown, S.; Lewis, B.; Luce, C.; Neuberg, S. Reinterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Maes, J. Sustainable development and emotions. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, W.P., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.; Collado, S. Experiences in Nature and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Setting the Ground for Future Research. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliegenschnee, M.; Schelakovsky, A. Umweltpsychologie und Umweltbildung: Eine Einführung aus humanökologischer Sicht; Facultas Universitäts Verlag: Viena, Austria, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, N.; Baror, S.; Bar, M. Overarching States of Mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollberger, S.; Bernauer, T.; Ehlert, U. Predictors of visual attention to climate change images: An eyetracking study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella-Brodrick, D.A.; Gilowska, K. Effects of nature (greenspace) on cognitive functioning in school children and adolescents: A systematic review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 1217–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Olvera-Alvarez, H.A.; Gross, J.J. The affective benefits of nature exposure. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2021, 15, e12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, P.; Wu, W.; Huo, C. Crucial to me and my society: How collectivist culture influences individual pro-environmental behavior through environmental values. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 454, 142211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Human Behavior and Environment: Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 6, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Un Pequeño Empujón; Editorial Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kohls, N.; Sauer, S.; Walach, H. Facets of mindfulness. Results of an online study investigating the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giluk, T.L. Mindfulness, Big Five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspy, D.J.; Proeve, M. Mindfulness and loving-kindness Meditation: Effects on connectedness to humanity and to the natural world. Psychol. Rep. 2017, 120, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.; Holder, M.D. Noticing nature: Individual and social benefits of a two-week intervention. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 12, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.D.; Eickhoff, S.; Pheasant, R.; Douglas, M.; Watts, G.; Farrow, T.; Hyland, D.; Kang, J.; Wilkinson, I.; Horoshenkov, K.; et al. The state of tranquility: Subjective perception is shaped by contextual modulation of auditory connectivity. NeuroImage 2010, 53, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Fu, E.-K.; Ma, J.; Sun, L.-X.; Huang, Z.; Cai, S.-Z.; Jia, Y. Empirical study of landscape types, landscape elements and landscape components of the urban park promoting physiological and psychological restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.; Hamilton, J.; Daily, G. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1249, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, J.R.; Pensini, P. Grounded by mother nature’s revenge. Exp. Psychol. 2023, 69, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Han, B.; Liu, P. The Trajectory of Anthropomorphism and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Serial Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P. Dispositional empathy with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, M. Two avenues for encouraging conservation behaviors. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2003, 10, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Guergachi, A.; Ngenyama, O.; Magness, V.; Hakim, J. Empathy: A unifying approach to address the dilemma of environment versus economy. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 5–8 July 2010; Volume 30, pp. 298–340. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, M.L. Empathy and prosocial behavior. In Handbook of Emotions; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Barrett, L.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 440–455. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Miller, P.A. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 1987, 101, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen, W.G.; Finlay, K. The role of empathy in improving intergroup relations. J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Empathizing with nature: The effect of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Betz, N.; Helmuth, B.; Coley, J. Conceptualizing Human-Nature Relationships: Implications of Human Exceptionalist Thinking for Sustainability and Conservation. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2023, 15, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, T.E.; Cousins, L.R. Environmental dispositions among school-age children: A preliminary investigation. Environ. Behav. 1985, 17, 725–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, E.; Breakwell, G.M. Factors predicting environmental concern and indifference in 13- to 16-year-olds. Environ. Behav. 1994, 26, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behaviour: A meta analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1986, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassinia, S.; Revonsuoa, A.; Castellottia, S.; Petrizzoa, I.; Benedettia, V.; Koivistoa, M. Processing of natural scenery is associated with lower attentional and cognitive load compared with urban ones. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waylen, K.A.; Fischer, A.; Mcgowan, P.J.K.; Thirgood, S.J.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Efect of Local Cultural Context on the Success of Community-Based Conservation Interventions. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Fazey, I.; Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C.; Robinson, G.M.; Evely, A.C. Integrating Local and Scientific Knowledge for Environmental Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1766–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corraliza, J.A.; Martín, R. Estilos de vida, actitudes y comportamientos ambientales. Medio Ambiente Y Comport. Hum. 2000, 1, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lomax, T.; Butler, J.; Cipriani, A.; Singh, I. Effect of nature on the mental health and well-being of children and adoles-cents: Meta-review. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2024, 225, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, M.; Gołos, P.; Stefan, F.; Taczanowska, K. Unveiling the Essential Role of Green Spaces during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Forests 2024, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, S.M.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A.; Helbich, M.; James, P. Nature’s contributions in coping with a pandemic in the 21st century: A narrative review of evidence during COVID-19. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, M.M.; Bardhan, M.; Safia Disha, A.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Parkinson, C.E.M.; Browning, M.H.; Labib, S.; Larson, L.R.; Haque, Z.; Rahman, A.; et al. Nature exposure and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A navigation guide systematic review with meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 356, 124284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, S.; Borja, Á.; Fleming, L.E.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; White, M.P.; Uyarra, M.C. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Lercher, P.; Browning, M.M.; Stoyanov, D.; Petrova, N.; Novakov, S.; Dimitrova, D.D. Does greenery experienced indoors and outdoors provide an escape and support mental health during the COVID-19 quarantine? Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Evans, M.J.; Tsuchiya, K.; Fukano, Y. A room with a green view: The importance of nearby nature for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ecol. Appl. 2023, 31, e2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spano, G.; D’este, M.; Giannico, V.; Elia, M.; Cassibba, R.; Lafortezza, R.; Sanesi, G. Association between indoor-outdoor green features and psychological health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: A cross-sectional nationwide study. Urban For. Urban Green 2021, 62, 127156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, M.M.; Bardhan, M.; İnan, H.E.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Disha, A.S.; Haque, Z.; Helmy, M.; Ashraf, S.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Shuvo, F.K.; et al. to urban green spaces and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from two low and lower-middle-income countries. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1334425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.; Neale, C.; Roe, J. Urban green space access, social cohesion, and mental health outcomes before and during COVID-19. Cities 2024, 152, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Passmore, H.; Lumber, R.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship. Int. J. Wellbeing 2021, 11, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.; Gasparatos, A.; Su, J.; Lam, D.; Grant, E.; Fukushi, K. Linking the nonmaterial dimensions of human-nature relations and human well-being through cultural ecosystem services. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S.; Colléony, A.; Conversy, P.; Maclouf, E.; Martin, L.; Torres, A.C.; Truong, M.X.; Prévot, A.C. Transformation of experience: Toward a new relationship with nature. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.; Robertson, N.; Lightfoot, C.; Smith, A.; Jones, C. Nature-Based Interventions for Psychological Wellbeing in Long-Term Conditions: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, X. Pro-Environmental Behavior Research: Theoretical Progress and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahbakhsh, I.; Bauch, C.; Anand, M. Modelling coupled human–environment complexity for the future of the biosphere: Strengths, gaps and promising directions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377, 20210382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ranking of Journals Consulted | Distribution (%) |

|---|---|

| Others | 52% |

| Journal of Environmental Psychology | 21% |

| Revista Investigaciones Geográficas | 10% |

| Sustainability | 8% |

| Ecosistemas. Revista Científica de Ecología y Medioambiente | 5% |

| Journal of Ecosystem Health and Sustainability | 4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buceta-Albillos, N.; Ayuga-Téllez, E. The Beneficial Interaction Between Human Well-Being and Natural Healthy Ecosystems: An Integrative Narrative Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030427

Buceta-Albillos N, Ayuga-Téllez E. The Beneficial Interaction Between Human Well-Being and Natural Healthy Ecosystems: An Integrative Narrative Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030427

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuceta-Albillos, Natividad, and Esperanza Ayuga-Téllez. 2025. "The Beneficial Interaction Between Human Well-Being and Natural Healthy Ecosystems: An Integrative Narrative Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030427

APA StyleBuceta-Albillos, N., & Ayuga-Téllez, E. (2025). The Beneficial Interaction Between Human Well-Being and Natural Healthy Ecosystems: An Integrative Narrative Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030427