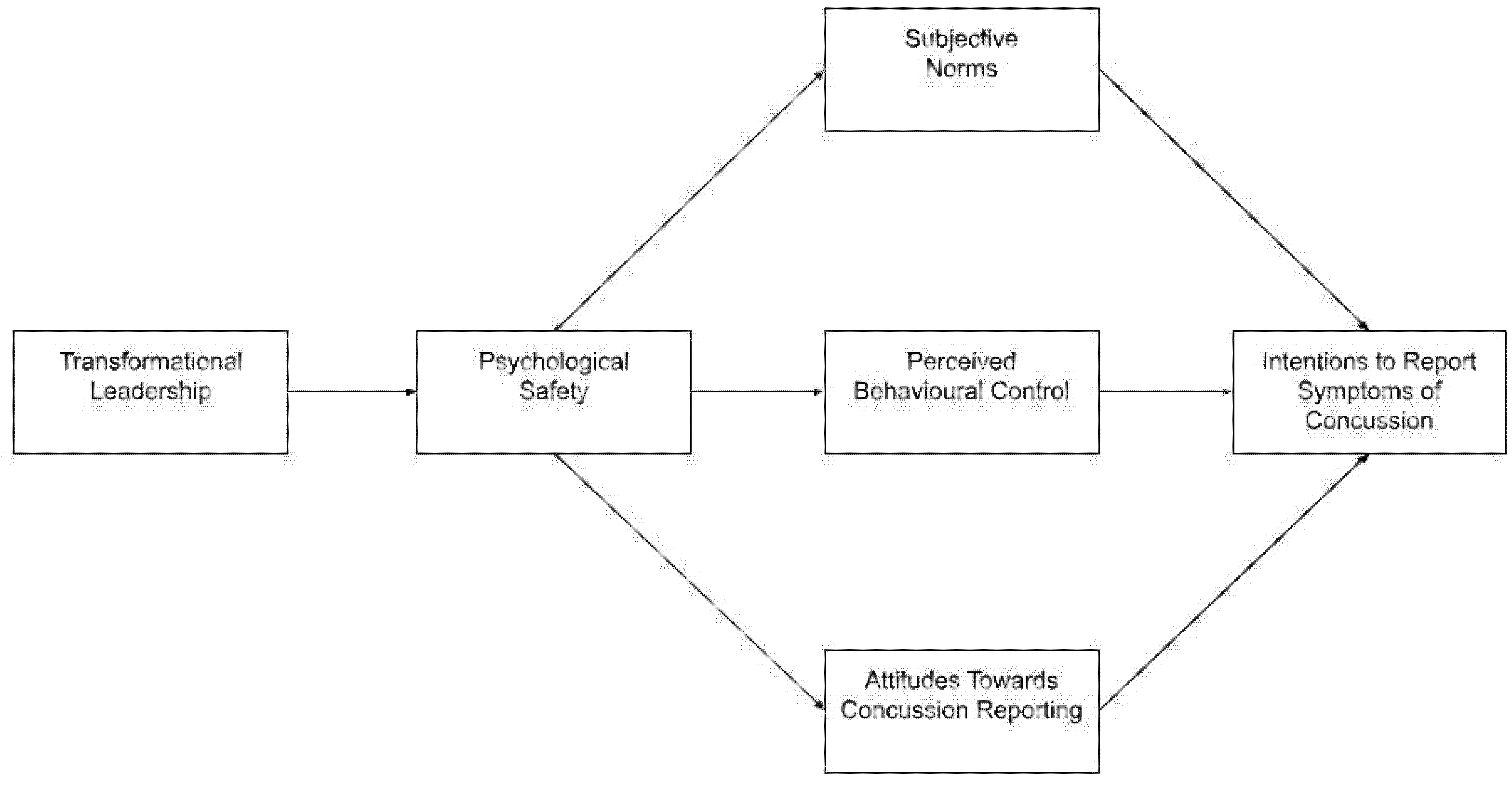

Transformational Leadership, Psychological Safety, and Concussion Reporting Intentions in Team-Sport Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Quantitative Measures

2.4.1. Transformational Leadership

2.4.2. Psychological Safety

2.4.3. Concussion Reporting Intentions

2.5. Qualitative Data Collection

Shona McCallin [international field hockey player and Olympic gold medallist] said that when she got a concussion in 2018, she was angry about being taken out of the game because she believed she was fine. However, later when she went to warm down with her teammates, she couldn’t run or co-ordinate herself and found it hard to talk.

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Analysis of Quantitative Data

2.6.2. Analysis of Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pearce, A.J.; Young, J.A.; Parrington, L.; Aimers, N. Do as I say: Contradicting beliefs and attitudes towards sports concussion in Australia. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimou, S.; Lagopoulos, J. Toward objective markers of concussion in sport: A review of white matter and neurometabolic changes in the brain after sports-related concussion. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, G.A.; Patricios, J.; Schneider, K.J.; Iverson, G.L.; Silverberg, N.D. Definition of sport-related concussion: The 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broglio, S.P.; Cantu, R.C.; Gioia, G.A.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Kutcher, J.; Palm, M.; McLeod, T.C.V. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: Management of sport concussion. J. Athl. Train. 2014, 49, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrea, M.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Marshall, S.W.; Barr, W.; Randolph, C.; Cantu, R.C.; Onate, J.A.; Yang, J.; Kelly, J.P. Acute effects and recovery time following concussion in collegiate football players. JAMA 2003, 290, 2556–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrave, M.; Williams, S. The epidemiology of concussion in professional rugby union in Ireland. Phys. Ther. Sport 2019, 35, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, R.; Finch, C.F.; Samra, D.; Baquie, P.; Cardoso, T.; Hope, D.; Orchard, J.W. Injuries in Australian Rules Football: An overview of injury rates, patterns, and mechanisms across all levels of play. Sports Health 2018, 10, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Alvarez, V.E.; Stein, T.D. The neuropathology of sport. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, 127, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.J.; Hoy, K.; Rogers, M.A.; Corp, D.T.; Maller, J.J.; Drury, H.G.K.; Fitzgerald, P.B. The long-term effects of sports concussion on retired Australian football players: A study using transcranial magnetic stimulation. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.H.; Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, W. Chronic neuropathologies of single and repetitive TBI: Substrates of dementia? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowinski, C.J.; Bureau, S.C.; Buckland, M.E.; Curtis, M.A.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Faull, R.L.M.; Grinberg, L.T.; Hill-Yardin, E.L.; Murray, H.C.; Pearce, A.J.; et al. Applying the Bradford Hill Criteria for causation to repetitive head impacts and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Frontiers in Neurology. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 938163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, A.C.; Cairns, N.J.; Dickson, D.W.; Folkerth, R.D.; Dirk Keene, C.; Litvan, I.; Perl, D.P.; Stein, T.D.; Vonsattel, J.-P.; Stewart, W.; et al. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, K.G.; Clugston, J.R.; Dec, K.; Hainline, B.; Herring, S.; Kane, S.F.; Kontos, A.P.; Leddy, J.J.; McCrea, M.; Poddar, S.K.; et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement on concussion in sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennon, M.J.; Brooker, H.; Creese, B.; Thayanandan, T.; Rigney, G.; Aarsland, D.; Hampshire, A.; Ballard, C.; Corbett, A.; Raymont, V. Lifetime traumatic brain injury and cognitive domain deficits in late life: The PROTECT-TBI cohort study. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corman, S.R.; Adame, B.J.; Tsai, J.Y.; Ruston, S.W.; Beaumont, J.S.; Kamrath, J.K.; Liu, Y.; Posteher, K.A.; Tremblay, R.; van Raalte, L.J. Socioecological influences on concussion reporting by NCAA Division 1 athletes in high-risk sports. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, J.S.; Caron, J.G.; Correa, J.A.; Bloom, G.A. Why Professional football players chose not to reveal their concussion symptoms during a practice or game. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2018, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraas, M.R.; Coughlan, G.F.; Hart, E.C.; McCarthy, C. Concussion history and reporting rates in elite Irish rugby union players. Phys. Ther. Sport 2014, 15, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, Z.Y.; Register-Mihalik, J.K.; Marshall, S.W.; Evenson, K.R.; Mihalik, J.P.; Guskiewicz, K.M. Disclosure and non-disclosure of concussion and concussion symptoms in athletes: Review and application of the socio-ecological framework. Brain Inj. 2014, 28, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.; Warrington, G.; Whelan, G.; McGoldrick, A.; Cullen, S. Concussion history, reporting behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge in jockeys. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2020, 30, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Register-Mihalik, J.; Baugh, C.; Kroshus, E.; YKerr, Z.; Valovich McLeod, T.C. A multifactorial approach to sport-related concussion prevention and education: Application of the Socioecological Framework. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Register-Mihalik, J.K.; Linnan, L.A.; Marshall, S.W.; McLeod, T.C.V.; Mueller, F.O.; Guskiewicz, K.M. Using theory to understand high school aged athletes’ intentions to report sport-related concussion: Implications for concussion education initiatives. Brain Inj. 2013, 27, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, D.M.; Galetta, K.M.; Phillips, H.W.; Dziemianowicz, E.M.S.; Wilson, J.A.; Dorman, E.S.; Torres, D.M.; Galetta, K.M.; Phillips, H.W.; Dziemianowicz, E.M.S.; et al. Sports-related concussion. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2013, 3, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroshus, E.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Goldman, R.E.; Austin, S.B. Norms, Athletic identity, and concussion symptom under-reporting among male collegiate ice hockey players: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, J.J.; Wyrick, D.L.; Rulison, K.L.; Sanders, L.; Mendenhall, B. Using the Integrated Behavioral Model to determine sport-related concussion reporting intentions among collegiate athletes. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pender, N.J.; Pender, A.R. Attitudes, subjective norms, and intentions to engage In health behaviors. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Brueller, D.; Dutton, J.E. Learning behaviours in the workplace: The role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2009, 26, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Donohue, R.; Eva, N. Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.C.; Fry, M.D.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Breske, M.P. Motivational climate and athletes’ likelihood of reporting concussions in a youth competitive soccer league. J. Sport Behav. 2019, 42, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, M.; Cohen, N.A.; Klein, K.J. The coevolution of network ties and perceptions of team psychological safety. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Sheaffer, Z.; Binyamin, G.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Shimoni, T. Transformational leadership and creative problem-solving: The mediating role of psychological safety and reflexivity. J. Creat. Behav. 2014, 48, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, M.L.; Fainshmidt, S.; Klinger, R.L.; Pezeshkan, A.; Vracheva, V. Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 70, 113–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ma, Z.; Yu, H.; Jia, M.; Liao, G. Transformational leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Explore the mediating roles of psychological safety and team efficacy. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Pan, W. A Cross-Level Examination of the process linking transformational leadership and creativity: The role of psychological safety Climate. Hum. Perform. 2015, 28, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Zi, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Gao, Y.; Tong, Y.; Song, L.; Liu, Y. Linking Esports to health risks and benefits: Current knowledge and future research needs. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosai, J.; Jowett, S.; Nascimento-Júnior, J.R.A.D. When leadership, relationships and psychological safety promote flourishing in sport and life. Sports Coach. Rev. 2023, 12, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, J.E.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Matkin, G.S. Applying mixed methods to leadership research: A review of current practices. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Mixed methods research: Contemporary issues in an emerging field. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2011; pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.; Plano-Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Method Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Callow, N.; Smith, M.J.; Hardy, L.; Arthur, C.A.; Hardy, J. Measurement of transformational leadership and its relationship with Team cohesion and performance level. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2009, 21, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Register-Mihalik, J.K.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; McLeod, T.C.V.; Linnan, L.A.; Mueller, F.O.; Marshall, S.W. Knowledge, attitude, and concussion-reporting behaviors among high school athletes: A preliminary study. J. Athl. Train. 2013, 48, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.; Arnold, R. A qualitative study of performance leadership and management in elite sport. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2011, 23, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; 265p. [Google Scholar]

- McCrow, J.; Beattie, E.; Sullivan, K.; Fick, D.M. Development and review of vignettes representing older people with cognitive impairment. Geriatr. Nurs. 2013, 34, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barter, C.; Renold, E. “I wanna tell you a story”: Exploring the application of vignettes in qualitative research with children and young people. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2000, 3, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szedlak, C.; Smith, M.; Day, M.; Callary, B. Using vignettes to analyze potential influences of effective strength and conditioning coaching on athlete development. Sport Psychol. 2018, 32, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Set Correlation and contingency tables. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 12, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.; McGannon, K.R. Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Y.-L.; Chan, Z.C.Y.; Chien, W.-T. Undertaking qualitative research that involves native Chinese people. Nurse Res. 2013, 21, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterill, S.T.; Fransen, K. Athlete leadership in sport teams: Current understanding and future directions. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 9, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedimyer, A.K.; Chandran, A.; Kossman, M.K.; Gildner, P.; Register-Mihalik, J.K.; Kerr, Z.Y. Concussion knowledge, attitudes, and norms: How do they relate? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, C.; Schoeman, M.; Brandt, C.; Patricios, J.; Van Rooyen, C. Concussion knowledge and attitudes among amateur South African rugby players. S. Afr. J. Sports Med. 2017, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarrie, K.L.; Gianotti, S.M.; Hopkins, W.G.; Hume, P.A. Effect of nationwide injury prevention programme on serious spinal injuries in New Zealand rugby union: Ecological study. Bmj 2007, 334, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.J.; DParry, K.; Humphries, C.; Phelan, S.; Batten, J.; Magrath, R. Duty of Karius: Media framing of concussion following the 2018 UEFA Champions League Final. Commun. Sport 2022, 10, 541–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liston, K.; McDowell, M.; Malcolm, D.; Scott-Bell, A.; Waddington, I. On being ‘head strong’: The pain zone and concussion in non-elite rugby union. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2018, 53, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderick, M. Adding insult to injury: Workplace injury in English professional football. Sociol. Health Illn. 2006, 28, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, H.; Welman, K.; Kraak, W. Concussion knowledge and attitudes amongst community club rugby stakeholders. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2020, 15, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Langdon, J.L.; McMillan, J.L.; Buckley, T.A. English professional football players concussion knowledge and attitude. J. Sport Health Sci. 2016, 5, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvinen-Barrow, M.; Pack, S.; Scheadler, T.R. Social support in sport injury and rehabilitaiton. In The Psychology of Sport Injury and Rehabilitation; Arvinen-Barrow, M., Clement, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 258–272. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, T.; Pfister, K.; Hagel, B.; Ghali, W.A.; Ronksley, P.E. The incidence of concussion in youth sports: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marar, M.; McIlvain, N.M.; Fields, S.K.; Comstock, R.D. Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am. J. Sports Med. 2012, 40, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berz, K.; Divine, J.; Foss, K.B.; Heyl, R.; Ford, K.R.; Myer, G.D. Sex-specific differences in the severity of symptoms and recovery rate following sports-related concussion in young athletes. Phys. Sportsmed. 2013, 41, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covassin, T.; Swanik, C.B.; Sachs, M.L. Epidemiological considerations of concussions among intercollegiate athletes. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2003, 10, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss-Farzanegan, S.J.; Chapman, B.; Wong, T.M.; Wu, J.; Bazarian, J.J. The relationship between gender and postconcussion symptoms after sport-related mild traumatic brain injury. PM&R 2009, 1, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.A.; Ganderton, C.; White, A.J.; Batten, J.; Howarth, N.; Downie, C.; Pearce, A.J. The times are they a-changing? Evolving attitudes in Australian exercise science students’ attitudes towards sports concussion. J. Sport Exerc. Sci. 2021, 5, 236–245. Available online: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/155468 (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- King, D.; Hume, P.; Gissane, C.; Clark, T. Semi-professional Rugby League players have higher concussion risk than professional or amateur participants: A pooled analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Main Theme | Sub-Theme | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Be accepting and non-judgemental | ‘… there’s no real, like no judgement among us. Overall, we’re pretty close. We have a laugh, it’s pretty good’. |

| ‘They [their teammates] can pretty much talk to me about anything and I can pretty much talk to them about anything’. | ||

| I think it’s about fostering a culture in which they are inclusive of all different people and inclusive of all different kinds of situations, and … the fact that they can come up to me or come up to anyone and speak about their issues. | ||

| Develop personal relationships | The majority of us have been together for the last 3 years. 3 or 4 years, so we are quite comfortable with one another, and new girls that come in, we welcome them quite well I feel’. | |

| ‘…because of our shared interest and passion for the game, I think we definitely get along…’ | ||

| ‘There is a lot of comradery and a lot of friendships … [and you] … hold each other accountable’. | ||

| Constantly talking to them and making sure that they are feeling welcome at every training session at every game. When they come to every training session, we will all go into the changing rooms so making sure I say hi to them each time and asking them how they are going and just acknowledging them all the time. | ||

| … lots of conversations were asking me about like you know where I’ve come from, how long I’ve been playing for and just talking about like other interests outside of basketball. I think that also really helps to build relationships. | ||

| … after games and training we might have a small snack together or sit outside like in the car park before we go home and talk and just sort of do these things. I think they are really important as it creates that sort of bond away from the pitch. | ||

| Encourage accountability | ‘He does that by showing up early to training. Calling upon people to be accountable for themselves’ |

| ‘I think the sort of expectation of being there on time and making sure we have the right equipment, the right kit and all that’. | ||

| Share personal experiences | … sometimes they would use their own personal experiences, which is motivating for a lot of us because if this person knows what it feels like to be in our position, then they feel like they understand the pressure of games and competitions. | |

| “Now we’re talking about concussion, I’m gonna give you my personal experience of how I got a concussion” and people will start to realise. OK, I haven’t suffered that just on my own. My coach suffered the same thing. | ||

| Be friendly and approachable | ‘You don’t always want them to be like an authority figure. You need to be able to have some sort of friendly relationship with them, almost like a friend that you can talk to’. | |

| My relationship with them I’d say is really, really good. He is quite laid back I’d say, he is also super approachable. He is super approachable, like legit going up to him and talking to him about how I’m feeling with footie and how I’m feeling off the field … he is very supportive … | ||

| He’s been really good with um injuries, like you know, if you have an injury or something is wrong, he’s always been saying, you know, “just tell me, I understand I’ll be here for you”. So even from the start he’s been really open he doesn’t care what it is like he’s like “I don’t care if you broke up with your boyfriend. If you’ve had a really bad day at school or work” like he’s been really good about us trying to make us feel comfortable to go, talk to him. | ||

| Provide personalised support | ‘… one to one talk with you … like sometimes our coaches call us in like a room and then we have this private talk’ | |

| ‘… coaches being able to say “you know what you can tell me anything. I’m here to listen, I understand” and that’. | ||

| Bring the group together | Partially, like it’s through the coach, sometimes we will do some drills that are more fun … as well as that it requires off the field stuff like sometimes, we might have a day we all just hang out and go to someone’s house, or, we will just have a chat. Or there is, in the warm down, someone might tell a story for example, that happened to them through the week. Erm, you know, it’s building that bit of chemistry off field, erm, or at training… | |

| Hiding symptoms | ‘She did keep a lot of her symptoms a secret from the coach, even though a lot of the girls knew’ |

| ‘Sometimes they hide it. Sometimes you see it’. | ||

| Barriers to reporting | If a player can get away with playing a game despite putting themselves at risk of being concussed further and injuring themselves further and damaging the brain further, I think a lot of players would take that risk purely for the game time of not being dropped or losing their positions or worrying about someone playing in their position and performing better. | |

| … if you’ve got a mild concussion symptom like maybe it’s just, they’re just feeling a little bit nauseous. Like maybe that could be seen as also a weak thing as well so you can. You should still be able to do this. | ||

| Those who haven’t had a concussion don’t understand what the person is going through so I feel like they don’t want to talk about it cause they just feel the other person will not understand. | ||

| Education and awareness | Having a coach that has the knowledge about concussions specifically, probably can help prevent more concussions in the future, because that allows them to understand what players are going through as such. | |

| Workshops and lots of discussions about the impacts of it and both long term and short term … It should be done from a grassroots level all the way through the professional athlete programmes just to make sure that people are really aware of the side effects. And you know the difficulties that come with having short-term and long-term concussion. | ||

| In Australian Aussie rules, they have just put in a rule that players need to have 12 days off if they’ve been concussed so they can’t play or train during that time. And I felt like because she had just had a concussion and this news … had just come out, I thought it was really poor that she was just able to like to play only like a few days after she did it. And she was feeling like, you know, quite dizzy during those games too. | ||

| I think if professional athletes spoke up more it would. Like signal to other athletes like so whatever level you’re playing that, yeah, it’s OK [to talk about concussion]. | ||

| I would feel comfortable like being able to talk about it [concussion] because of that comfortable open environment and being able to talk about it with them and like just ‘cause it’s like another injury, they’ll feel like it’s another injury. | |

| … it’s about creating a good culture at the start of the season … and actually addressing the issue. … having a nice overview of the plan just as, not only as a team but also for you individually … If someone does feel the need to come speak out, then they can speak to a couple of people or speak to the coach or erm, you know, if they feel they are at risk of a concussion they can actually come up to the coach and they can feel like, I don’t feel safe playing … It’s about fostering a culture from early on before the season starts, that there is a safe environment where someone can come up and say whatever they please. | ||

| … I think we would be quite open about it because we understand that people have their own lives outside of soccer and having a concussion in soccer has to be dealt with in a quite cautious manner. Because if something else goes bad, then their whole life could be impacted. | ||

| ‘… they would certainly talk to me and say I really have this bad headache like I’m starting to feel dizzy … so I will actually inform … coaches to actually do something about it’. | |

| I wouldn’t go up to the coach and say directly what’s wrong because I feel like that would be my teammates responsibility. But I might go up to the coach and say I don’t think so and so is doing so well, he just seems a bit off today or doesn’t seem like himself. | ||

| It’s a very sensitive thing for me. Very sensitive because some of them tell it to me and then, they tell me not to tell the coach, not to tell anyone, and if I tell someone that makes me feel like I just betrayed them, so yeah, it’s a very sensitive thing, but I know they need help … I consider my relationship to them and also like my responsibilities. | ||

| If their wish was to keep it a bit more private or a bit more reserved, then I would keep it that way … But I think if the problem was getting really bad and was becoming an issue … then I would talk to the coach about it. … I think I would tell the coach only if the person told me to, I’d only ever tell the coach if they couldn’t talk to the coach and really wanted to talk about it. Or erm, I think or, I’d just not talk to the coach at all, and make sure, and constantly check up on the person themselves. | ||

| Be supportive and empathetic | In the past, whenever someone’s been injured or whenever someone’s had a concussion injury, everyone has been super, super supportive. Asking if they are alright or I think with concussion they really know the severity. And concussion is a big factor in Aussie Rules Football. I think the whole game usually stops and especially in a team we are quite caring to the fact we know they can’t come back for the rest of the game and that they will have to deal with those issues. So yeah, we are quite knowledgeable about someone getting a concussion and really just do our best to erm, just get around him and do our best to make sure he feels alright considering. |

| ‘If another one of the players had a concussion before and if the coach is showing that he can support those players, then they’ll feel more comfortable and able to tell [and talk to] the coach’ | ||

| ‘Allowing that coach to talk to the players. And say I understand what you’re going through, we will work through it with you, erm, and you will be back on the pitch in no time’ … and … ‘going to see the player who has just been concussed and encouraging that in the future they will be able to play again. | ||

| Outline plans for returning to play | … a plan in place to get you back to playing in a safe manner and also like give you opportunities and you don’t have to feel like that you have to go back early or you have to go back for a period of time just because you have to make sure that you want to keep your spot like I think we need to give like athletes confidence that they’re going to, you know, come back. | |

| Remove concussed players | She just wanted to play … but she wasn’t thinking about the effects of what concussion can actually do to her in the short and the long term. And like the coaches just let it happen even though they knew that she was concussed. So, I think that was a really poor thing by them. | |

| ‘That kind of signals to me that the coach doesn’t have as much trust in other point guards in the team’ … and … ‘That was disappointing to see from that aspect of like you know, he’s wanting a concussed player to play instead of like a fully fit player’. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batten, J.; Smith, M.J.; Young, J.; Braim, A.; Jull, R.; Samuels, C.; Pearce, A.J.; White, A.J. Transformational Leadership, Psychological Safety, and Concussion Reporting Intentions in Team-Sport Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030393

Batten J, Smith MJ, Young J, Braim A, Jull R, Samuels C, Pearce AJ, White AJ. Transformational Leadership, Psychological Safety, and Concussion Reporting Intentions in Team-Sport Athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030393

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatten, John, Matthew J. Smith, Janet Young, Abi Braim, Rebecca Jull, Callum Samuels, Alan J. Pearce, and Adam J. White. 2025. "Transformational Leadership, Psychological Safety, and Concussion Reporting Intentions in Team-Sport Athletes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030393

APA StyleBatten, J., Smith, M. J., Young, J., Braim, A., Jull, R., Samuels, C., Pearce, A. J., & White, A. J. (2025). Transformational Leadership, Psychological Safety, and Concussion Reporting Intentions in Team-Sport Athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030393