Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge and Perspectives on Behavioral Risk Factors Contributing to Non-Communicable Diseases: A Qualitative Study in Bushbuckridge, Ehlanzeni District, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Population and Sampling

Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Measures to Ensure Trustworthiness

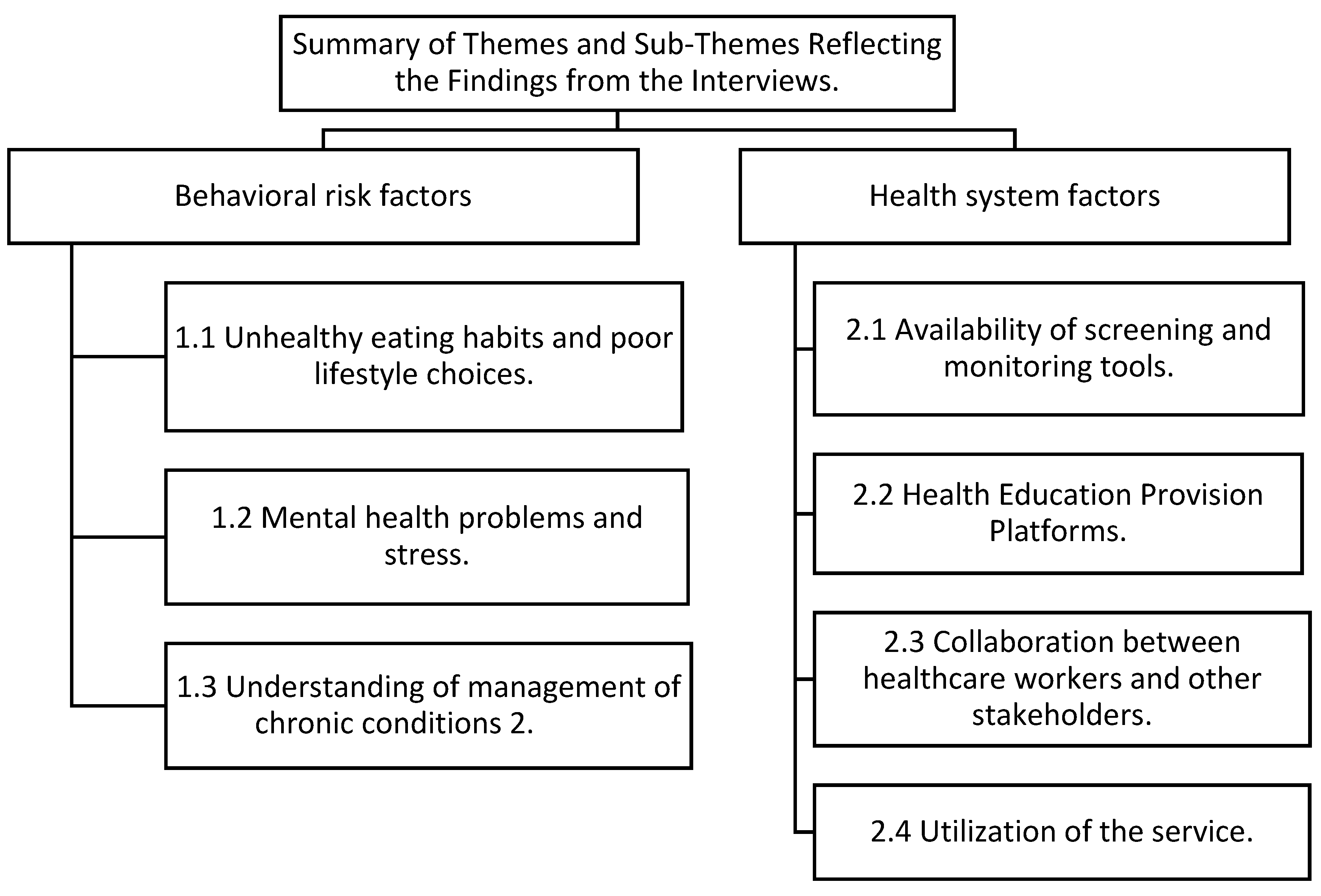

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Behavioral Risk Factors

3.1.1. Subtheme 1.1 Unhealthy Eating Habits and Poor Lifestyle Choices

“…mostly I think here could be diet and “yah”, I think I could diet because they eat everything and I think alcohol because here everyone drinks from grandmother, mother even children…”(HCW 4, female, aged 56)

Additionally, alcohol consumption appears to be prevalent across all age groups, raising further concerns about overall dietary and lifestyle habits.

3.1.2. Subtheme 1.2 Mental Health Problems and Stress

“Err” when I see to the side of female is stress, they are having stress, they think too much than males…”(HCW 3, female, aged, 37)

“You mean hypertension only” “ooh” both, it is lifestyle, you find that a person has stress and he/she does not have a person to share with like if a person has lost a child or husband through death, this person thinks too much…”(HCW 5, female, aged 45)

3.1.3. Subtheme 1.3 Understanding of Management of Chronic Conditions

… “Err, in many cases visiting Doctors are the one teaching us in relation to hypertension and Diabetes prevention and management, but no workshop was done, even if the workshop is done, the teaching is not mainly on Diabetes and hypertension.”(HCW 1, male, aged 37)

… “Mm, as for me I have not attended any workshop about prevention and management of hypertension and diabetes. I only have little information from the previous hospital where I was working before, I came here. Apart from training we depend on visiting doctors for in-service education regarding the management of hypertension and diabetes when they visit our facility every Tuesday.”(HCW 2, female, aged 37)

… “No, as for me I have not attended any training regarding behavioral risk factors for hypertension and Diabetes, I just know how to manager patient because I just read the books and working alongside with doctors, we hear them, and they teach.”(HCW 3, female, aged 37)

3.2. Theme 2: Health System Factors

3.2.1. Sub-Theme 2.1: Availability of Screening and Monitoring Tools

The participants highlighted that they lack screening and monitoring equipment to assist them in caring for the patients that are having chronic conditions. The lack of working equipment can hinder the quality of care of patients with hypertension and Diabetes.

… “Err, when coming to Hypertension and Diabetes, our health program is integrated with other stakeholders such as community health workers, we work together with community healthcare workers who help us to trace patients who defaulted their treatment and to add on that they go door to door with a machine that they use to test sugar and if they detect abnormal sugar level they refer them to the clinic for further management however currently they do not have a machine to test hypertension.”(HCW 1, male, aged 37)

… “Home base carers, we work with them in this way, when they do home visits, they give health education about lifestyle in the villages, and we also offered them machines to check blood sugar within the villages, but we did not give them a machine to check hypertension…”(HCW 3, female, aged 37)

3.2.2. Sub-Theme 2.2: Health Education Provision Platforms

… “Mm”, we give them health education, teaching them about eating of healthy diet, encouraging them to exercise, avoid stressful situation although it is not easy, and we also give them treatment and encourage them to take it as prescribed”….(HCW 2, female, aged 44)

… “Ok, err that one is through health education, each morning before we start working…in all the patient whether children or whatsoever, we teach them about hypertension, diabetes, HIV, we teach them, I think that one will assist”…(HCW 6, male, aged 36)

… “Err, in the morning we give health education and it depend on what health education is given that day, when you come to the consultation room I give one on one health education, all the information is given, if the BP is OK we do praise the patient wow this BP is nice you should keep it like that and we give information to prevent, yah to prevent. There is a specific day for health education not every day” …(HCW 4, females, aged 45)

3.2.3. Sub-Theme 2.3: Collaboration Between Healthcare Workers and Other Stakeholders

… “Err, when coming to Hypertension and Diabetes, our health program is integrated with other stakeholders such as community health workers, we work together with community healthcare workers who help us to trace patients who defaulted their treatment and to add on that they go door to door with a machine that they use to test sugar and if they detect abnormal sugar level they refer them to the clinic for further management however currently they do not have a machine to test hypertension”…(HCW 1, male, aged 37)

…“Err, we call them CHW, they work there in the field, they check chronic patient in their home, they bath those who are unable to bath, they collect medication for patients who are unable to come and collect and some here as you saw them on the table and since we do not have help desk nurses, they work as our help desk nurses and they also give patient sputum bottles”…(HCW 8, male, aged 53)

3.2.4. Sub-Theme 2.4: Utilization of the Service

… “Err, the community do utilize our services and we work together with them however in most cases they do not comply to our instructions such as return dates given to them but some of the community members do comply to our instructions”…(HCW 1, male, aged 37)

… “Mmm, according to me I see the community using our services effectively because when they are sick, they come to our clinic for consultation”……(HCW 2, female, aged 44)

… “Yes, they use our service in place effective just because they hypertension is controlled, diabetes is controlled since we have doctor “For” visiting and teach the patient about lifestyle”…(HCW 3, female, aged 37)

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. World Health Organization Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2022; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Owopetu, O.F.; Adebayo, A.M.; Popoola, O.A. Behavioural risk factors for non-communicable diseases among undergraduates in South-west Nigeria: Knowledge, prevalence and correlates: A comparative cross-sectional study. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2020, 61, E568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamkuemah, M. The epidemiology of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDS) and NCD Risk Factors in Adolescents & Youth Living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa. 2021. Available online: https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/35558 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Sharma, M.; Gaidhane, A.; Choudhari, S.G. A Comprehensive Review on Trends and Patterns of Non-communicable Disease Risk Factors in India. Cureus 2024, 16, e57027. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11046362/ (accessed on 7 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Abbass, M.M. Unhealthy dietary habits and obesity: The major risk factors beyond non-communicable diseases in the eastern mediterranean region. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 817808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budreviciute, A.; Damiati, S.; Sabir, D.K.; Onder, K.; Schuller-Goetzburg, P.; Plakys, G.; Katileviciute, A.; Khoja, S.; Kodzius, R. Management and prevention strategies for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 574111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganju, A.; Goulart, A.C.; Ray, A.; Majumdar, A.; Jeffers, B.W.; Llamosa, G.; Cañizares, H.; Ramos-Cañizares, I.J.; Fadhil, I.; Subramaniam, K.; et al. Systemic Solutions for Addressing Non-Communicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, M.Y.; Chisholm, D.; Watts, R.; Waqanivalu, T.; Prasad, V.; Varghese, C. Cost-effectiveness of population level and individual level interventions to combat non-communicable disease in Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: A WHO-CHOICE analysis. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, J.F.; Elborn, J.S.; Lansberg, P.; Javed, A.; Tesfaye, S.; Rugo, H.; Duddi, S.R.D.; Jithoo, N.; Huang, P.H.; Subramaniam, K.; et al. Bridging the “Know-Do” Gaps in Five Non-Communicable Diseases Using a Common Framework Driven by Implementation Science. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2023, 15, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkomy, S.; Jackson, T. WHO non-communicable diseases Global Monitoring Framework: Pandemic resilience in sub-Saharan Africa and Low-income Countries. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 95, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoli, P.; Mayige, M.; Kagaruki, G.; Mori, A.; Macha, E.; Mutagaywa, R.; Momba, A.; Peter, H.; Willilo, R.; Chillo, P.; et al. Mid-level healthcare workers knowledge on non-communicable diseases in Tanzania: A district-level pre-and post-training assessment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onagbiye, S.O.; Tsolekile, L.P.; Puoane, T. Knowledge of Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors among Community Health Workers in South Africa. Open Public Health J. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.; Nagar, B.; Thomas, G.; Badri, M.; Ntusi, N.B.A. Health practitioners’ state of knowledge and challenges to effective management of hypertension at primary level: Cardiovascular topics. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2011, 22, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yenit, M.K.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Gelaye, K.A.; Gezie, L.D.; Tesema, G.A.; Abebe, S.M.; Azale, T.; Shitu, K.; Gyawali, P. An Evaluation of Community Health Workers’ knowledge, attitude and personal lifestyle Behaviour in Non-communicable Disease Health Promotion and Their Association with self-efficacy and NCD-Risk perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melariri, H.I.; Kalinda, C.; Chimbari, M.J. Training, Attitudes, and Practice (TAP) among healthcare professionals in the Nelson Mandela Bay municipality, South Africa: A health promotion and disease prevention perspective. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, C.; Guetterman, T.C. Mixed methods in accounting: A field based analysis. Meditari. Account. Res. 2019, 27, 921–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati-Sarcheshme, M.; Mahdizdeh, M.; Tehrani, H.; Jamali, J.; Vahedian-Shahroodi, M. Women’s perception of barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer Pap smear screening: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e072954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A.; Soltani, S.; Abdolshahi, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. Healthy and unhealthy dietary patterns and the risk of chronic disease: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, K.R.; Shipherd, J.C.; Collins, K.M.; Gunn, H.A.; Rubin, R.O.; Rood, B.A.; Pantalone, D.W. Coping, resilience, and social support among transgender and gender diverse individuals experiencing gender-related stress. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2022, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.; Kgatla, N.; Sodi, T.; Musinguzi, G.; Mothiba, T.; Skaal, L.; Makgahlela, M.; Bastiaens, H. Facilitators and barriers in prevention of cardiovascular disease in Limpopo, South Africa: A qualitative study conducted with primary health care managers. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Wallace, E.; Clyne, B.; Boland, F.; Fortin, M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community setting: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otieno, C.O.; Makara, M.W.K.; James, N.N.; Liyai, G.M. Towards an Effective Communication in the Care of Patients with Long Term Disease in Kenya via Cybernetic—A Systematic Review. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2094–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, L.; Lawrenson, J.G.; Cartwright, M.; Crosby-Nwaobi, R.; Burr, J.M.; Gardner, P.; Anderson, J.; Presseau, J.; Ivers, N.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. Barriers and enablers to diabetic eye screening attendance: An interview study with young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2022, 39, e14751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melariri, H.I.; Kalinda, C.; Chimbari, M.J. Patients’ views on health promotion and disease prevention services provided by healthcare workers in a South African tertiary hospital. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, L.A.; Wolever, R.Q.; Bechard, E.M.; Snyderman, R. Patient engagement as a risk factor in personalized health care: A systematic review of the literature on chronic disease. Genome Med. 2014, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gu, D.; Li, S. Effectiveness of Person-Centered Health Education in the General Practice of Geriatric Chronic Disease Care. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2024, 30, 349. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=10786791&AN=180309166&h=QZPFVHu%2B%2BdgUTfqacRZtn8rG3zafAUq7h1LPkAl4pdH4IS%2FMyxqROShmQHzCHbSSTPkJ9ohsMmpGmx2Xq1AZZg%3D%3D&crl=c (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Williamson, T.M.; Moran, C.; McLennan, A.; Seidel, S.; Ma, P.P.; Koerner, M.L.; Campbell, T.S. Promoting adherence to physical activity among individuals with cardiovascular disease using behavioral counseling: A theory and research-based primer for health care professionals. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 64, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.B.; Fernandes, S.; Domingos, J.; Castro, C.; Romão, A.; Graúdo, S.; Rosa, G.; Franco, T.; Ferreira, A.P.; Chambino, C. Motivational strategies used by health care professionals in stroke survivors in rehabilitation: A scoping review of experimental studies. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1384414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Golin, C.E.; Jones, C.D.; Ashok, M.; Blalock, S.J.; Wines, R.C.M.; Coker-Schwimmer, E.J.; Rosen, D.L.; Sista, P.; Lohr, K.N. Interventions to Improve Adherence to Self-administered Medications for Chronic Diseases in the United States: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pseudo Names | Age | Gender | Level of Education | Marital Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCW 1 | 37 | Male | Tertiary | Married |

| HCW 2 | 44 | Female | Tertiary | Married |

| HCW 3 | 37 | Female | Tertiary | Married |

| HCW 4 | 56 | Female | Tertiary | Single |

| HCW 5 | 43 | Female | Tertiary | Widowed |

| HCW 6 | 36 | Male | Tertiary | Married |

| HCW 7 | 53 | Male | Tertiary | Married |

| HCW 8 | 53 | Male | Tertiary | Single |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pilusa, T.D.; Ntimana, C.B.; Maphakela, M.P.; Maimela, E. Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge and Perspectives on Behavioral Risk Factors Contributing to Non-Communicable Diseases: A Qualitative Study in Bushbuckridge, Ehlanzeni District, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030343

Pilusa TD, Ntimana CB, Maphakela MP, Maimela E. Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge and Perspectives on Behavioral Risk Factors Contributing to Non-Communicable Diseases: A Qualitative Study in Bushbuckridge, Ehlanzeni District, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030343

Chicago/Turabian StylePilusa, Thabo D., Cairo B. Ntimana, Mahlodi P. Maphakela, and Eric Maimela. 2025. "Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge and Perspectives on Behavioral Risk Factors Contributing to Non-Communicable Diseases: A Qualitative Study in Bushbuckridge, Ehlanzeni District, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030343

APA StylePilusa, T. D., Ntimana, C. B., Maphakela, M. P., & Maimela, E. (2025). Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge and Perspectives on Behavioral Risk Factors Contributing to Non-Communicable Diseases: A Qualitative Study in Bushbuckridge, Ehlanzeni District, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030343