Pilot Study Exploring the Perspectives of Canadian Clients Who Received Digitally Delivered Psychotherapies Utilized for Trauma-Affected Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participant Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Tools and Measures

2.3.1. Survey Based on the Alberta Quality Matrix for Health Survey

2.3.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Survey

- Effort Expectancy: the degree of ease associated with using the technology. If participants perceived psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations to have low Effort Expectancy, it would be expected that they would be more likely to use it.

- Performance Expectancy: assesses whether the participant believed that the technology would improve the performance of the job they were trying to complete. If belief in psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations was high, participants would be more likely to use the technology.

- Behavioral Intention: the degree to which participants had a conscious plan to utilize technology. This construct, in turn, predicts Use Behavior and technology acceptance.

- Social Influence: the extent to which individuals surrounding the participant perceived the usefulness of psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations and how much these important others influenced the participant’s use of psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations.

- Facilitating Conditions: the extent to which conditions, such as organizational and technical infrastructure, surrounding the participant support the use of psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations.

- Use Behavior: the extent to which participants used psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations.

2.3.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Client Participant Demographics

3.2. Survey Results

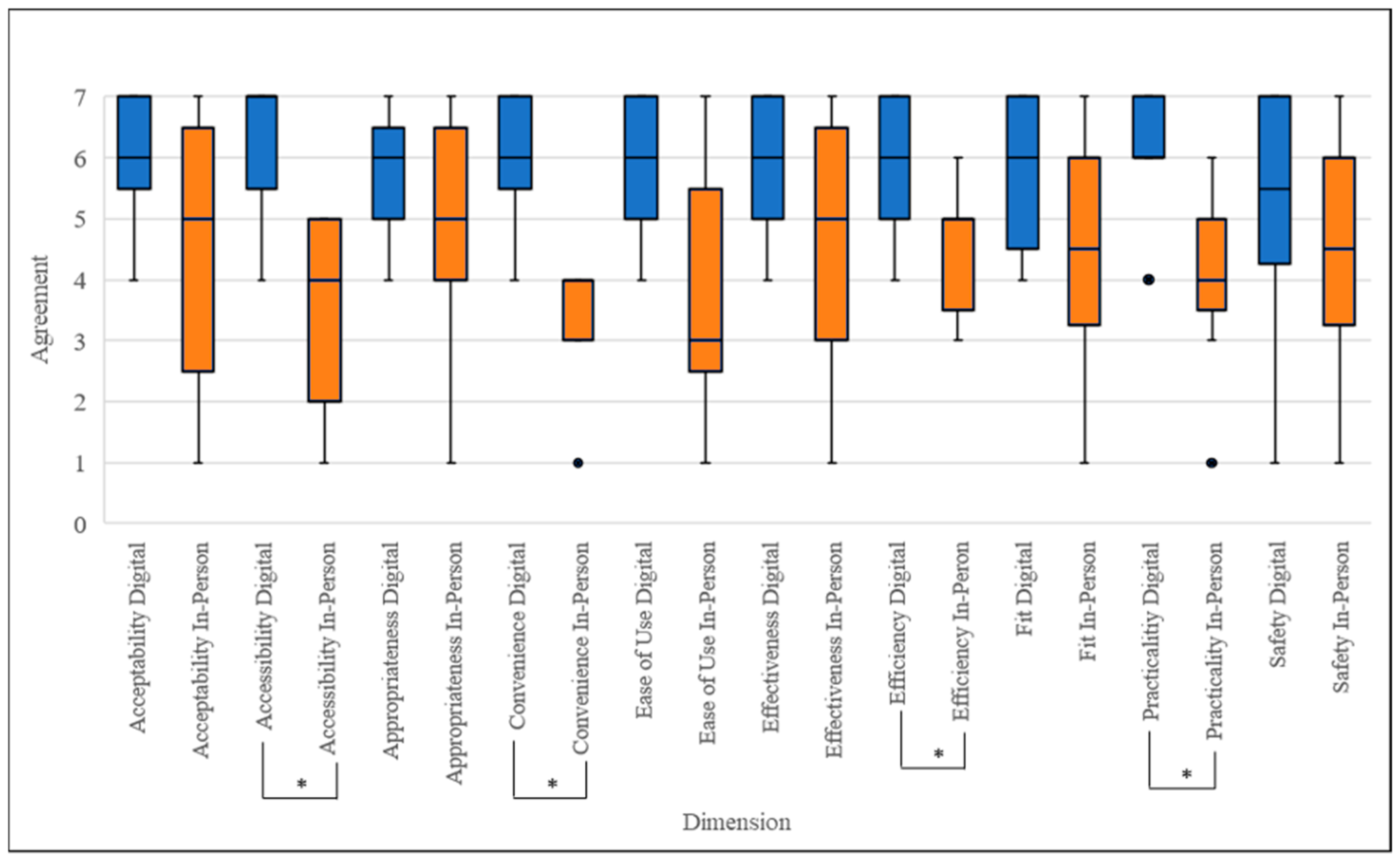

3.2.1. Survey Based on Alberta Quality Matrix for Health Results

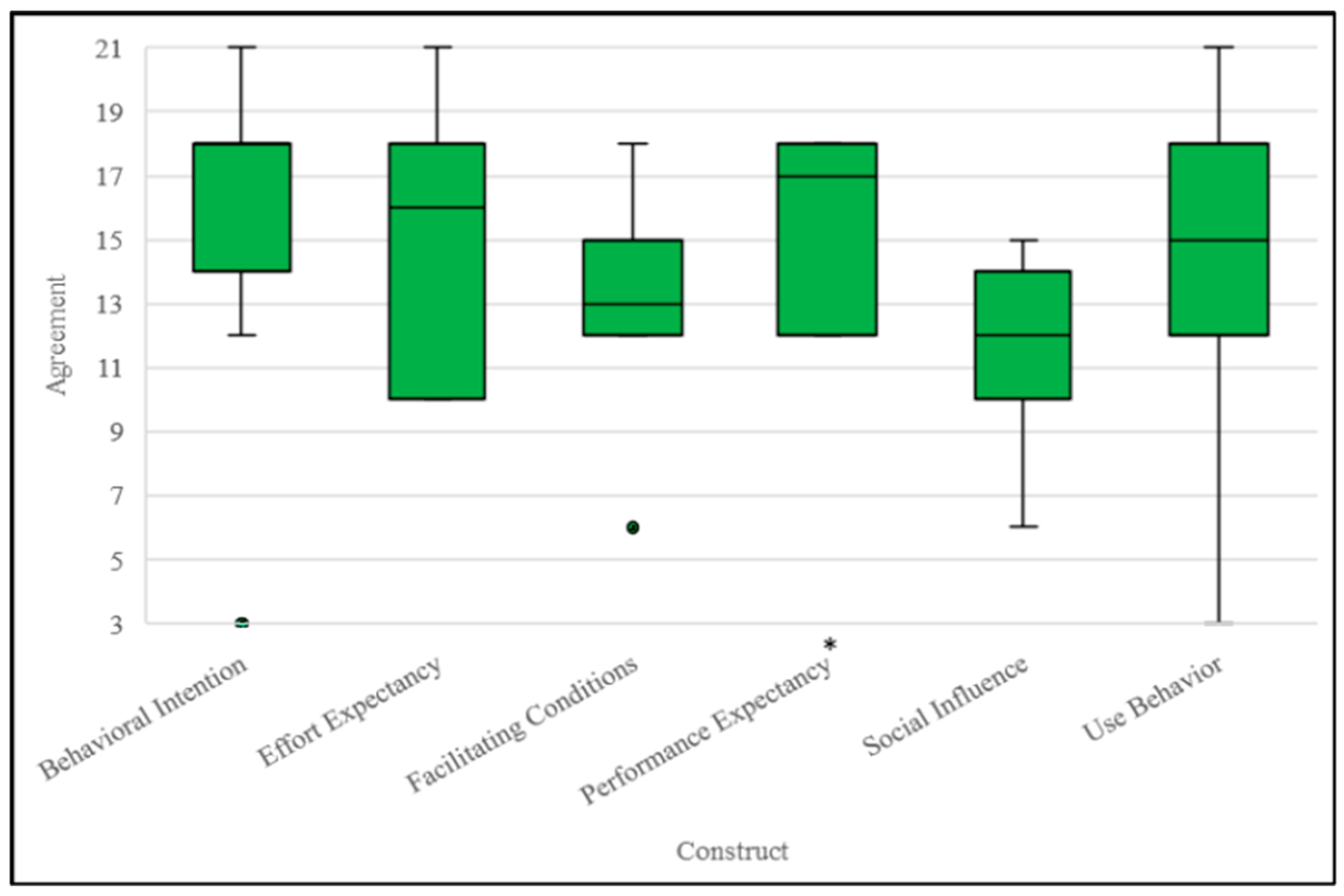

3.2.2. Survey Based on Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Results

3.3. Interview Results

3.3.1. Theme 1: Creating Connection While Online

“I didn’t because I had used it. I’ve been using it since the beginning of COVID with my work that I was doing. I felt just as close to the virtual therapist as the in-person one. I did feel a real sense of of bonding with them and feeling as if I could disclose things and talk to them[.] I didn’t find it different in that sense[.] I made a very strong connection with the therapist very quickly. She was excellent. Very experienced, and I felt very comfortable with her.”[Client participant 4]

3.3.2. Theme 2: Improved Access to Care

“I did find it much easier to schedule, schedule around where I was, where [my therapist was]. And it was also easy for adjustments too if I needed to postpone or change or if he needed some extra time from something else. It was a lot easier to communicate [and] arrange schedules that way, which made for less [absences or appointments] missed.”[Client participant 1]

“I mean, if you’re a, let’s say you’re a single mother with two kids and you know you can’t make it downtown or you can’t make it to wherever right to go and do your sessions, then you know you have to skip this one, skip that one and then eventually you’re just like, I’m not even going to bother phoning them anymore. Versus, oh, it’s 1:00 I should turn on my computer and have a quick little chat with somebody here who can help me through a lot. I think it would help a lot of people[.]”[Client participant 3]

3.3.3. Theme 3: Differing Experiences Working Digitally

“For some reason I didn’t get as emotional as [I] knew I probably would have if I’d been in person.”[Client participant 4]

“[It added] more stress [for] me going into therapy back then at the [Occupational Stress Injury] clinic, [being] over medicated [and] driving back and forth, not understanding what was going on in my head[...]”[Client participant 2]

3.3.4. Theme 4: Difficulties with Digital Delivery

“He had to be able to talk to me through[,] to talk me through [going] on the Jane chat thing that we, right? He had to talk me through it over the phone, right, because I’m not[,] I’m not into all this stuff so[...] [I was frustrated because] I hate computers, data, and I was just like, “I don’t know how to operate it.””[Client participant 3]

“Yes, so that was a little awkward because, you know, if somebody was in my house and I had to go to a different room, there was always the thought of “Can they hear me? Are they listening?” I mean, generally I was not in a house of somebody I couldn’t trust anyways. But, you know, those are private sessions that you want to keep to yourself.”[Client participant 1]

“There [are] certain things about [my] experiences that I would prefer my family not to know about[,] that I keep to myself, right? You know, [my] five year old is sitting on the couch right now while we’re doing this. So, you know, that’s a little bit of a negative.”[Client participant 3]

3.3.5. Theme 5: Continuing to Improve Accessibility of Care

“Yeah, I think maybe something like you’re offering them both and if people are selecting virtual because they can get in quicker, letting them know that it could be transitioned [by] agreement or in particular what the therapist thinks would be best if you could transition into in-person somewhere down the road during the therapy. If that’s [what] looks [to be] needed. You wouldn’t get absolutely stuck with one if [you] chose it. Similarly, you could switch from in-person to virtual, maybe as you’re coming to the end of your therapy.”[Client participant 4]

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health (SCMH) [Internet]. Statistics Canada; 2021. Available online: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5330 (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; text rev.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; 1120p. [Google Scholar]

- Heber, A.; Testa, V.; Groll, D.; Ritchie, K.; Tam-Seto, L.; Mulligan, A.; Sullo, E.; Schick, A.; Bose, E.; Jabbari, Y.; et al. Glossary of terms: A shared understanding of the common terms used to describe psychological trauma, version 3.0. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2023, 43, S1–S999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; Macphee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental disorder symptoms among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, H.C.; Landry, C.A.; Ogunade, A.; Carleton, R.N.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D. Why do public safety personnel seek tailored internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy? An observational study of treatment-seekers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Til, L.; Sweet, J.; Poirier, A.; McKinnon, K.; Sudom, K.; Dursun, S. Well-Being of Canadian Regular Force Veterans: Findings from LASS 2016 Survey; Technical Report; Veterans Affairs Canada Research Directorate: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2017; 41p. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Martínez-González, M.B.; Benitez-Agudelo, J.C.; Navarro-Jimenez, E.; Beltran-Velasco, A.I.; Ruisoto, P.; Arroyo, E.D.; Laborde-Cárdenas, C.C.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental disorders. A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Cycle 2: Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) During the COVID-19 Pandemic [Internet]. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2021. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/cycle-2-symptoms-posttraumatic-stress-disorder-covid-19-pandemic.html (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Torous, J.; Keshavan, M. Covid-19, mobile health and serious mental illness. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 218, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2022. Available online: www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Philippe, T.J.; Sikder, N.; Jackson, A.; Koblanski, M.E.; Liow, E.; Pilarinos, A.; Vasarhelyi, K. Digital health interventions for delivery of mental health care: Systematic and comprehensive meta-review. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e35159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-MacDonald, L.; Jones, C.; Sevigny, P.; White, A.; Laidlaw, A.; Voth, M.; Mikolas, C.; Heber, A.; Greenshaw, A.; Brémault-Phillips, S. The experience of key stakeholders during the implementation and use of trauma therapy via digital health for military, veteran, and public safety personnel: Qualitative thematic analysis. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e26369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, J.; Schueller, S.M. Digital mental health deserves investment but the questions are which interventions and where? AJOB Neurosci. 2022, 13, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.; Miguel-Cruz, A.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Cruikshank, E.; Baghoori, D.; Chohan, A.K.; Laidlaw, A.; White, A.; Cao, B.; Agyapong, V.; et al. Virtual trauma-focused therapy for military members, veterans, and public safety personnel with posttraumatic stress injury: Systematic scoping review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e22079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, R.L.; Castelli, P.; La Rosa, C.; Zucchi, T.; Onofri, A. COVID-19, isolation, quarantine: On the efficacy of internet-based eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for ongoing trauma. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. What You Need to Know Before Choosing Online Therapy [Internet]. American Psychological Association. 2015. Available online: www.apa.org/topics/telehealth/online-therapy (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Titov, N.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Nielssen, O.; Mohr, D.C.; Andresson, G.; Dear, B.F. From research to practice: Ten lessons in delivering digital mental health services. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattie, E.G.; Stiles-Shields, C.; Graham, A.K. An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuty, K.; Almond, M.K. Remote access therapy for veterans with psychological problems: Current state of the art. Mil. Med. 2020, 185, e1046–e1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beahm, J.D.; McCall, H.C.; Carleton, R.N.; Titov, N.; Dear, B.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D. Insights into internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for public safety personnel: Exploration of client experiences during and after treatment. Internet Interv. 2021, 26, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, G.; Basu, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Craske, M.G.; McEvoy, P.; English, C.L.; Newby, J.M. Computer Therapy for the Anxiety and Depression Disorders is Effective, Acceptable and Practical Health Care: An Updated Meta-Analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 55, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G.; Cuijpers, P.; Riper, H.; Hedman-Lagerlof, E. Internet-Based vs. Face-to-Face Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Psychiatric and Somatic Disorders, An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018, 47, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spytska, L. The use of virtual reality in the treatment of mental disorders such as phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder. SSM Ment. Health 2024, 6, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triscari, S.; Casu, M.; Uccelli, E.; Vitale, N.M.; Rapisarda, V.; Fakhrou, A.; Caponnetto, P. Virtual Reality Neurofeedback Training combined with Trauma-Informed Motivational Interviewing for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Preprints 2024, 2024101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. Healthcare Quality and Safety Management: A Framework for Alberta; Health Quality Council of Alberta: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2017; 52p. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.; Allen, R.R.; Aquin, C.R.; Bright, K.S.; Brown, M.R.G.; Burback, L.; Winkler, O.; Jones, C.; Hayward, J.; Wells, K.; et al. Current and future implementation of digitally delivered psychotherapies: An exploratory mixed-methods investigation of client, clinician, and community partner perspectives. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, S.; Schlundt, D.; Smith, P. Community-engaged research perspectives: Then and now. Acad. Pediatr. 2013, 13, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, L.; Moore, E.; Rein, A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: Moving from theory to practice. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2015, 4, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patridge, E.F.; Bardyn, T.P. Research electronic data capture (REDCap). J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliot, V.; Fernandex, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2001; 360p.

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using Zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 28.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, K.A.; Peluchette, J.V.; Aghakhani, N. Virtual work meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic: The good, bad, and ugly. Small Group Res. 2022, 53, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Stadnick, N.A.; Ceballos-Corro, E.; Castro Jr, J.; Mallard-Swanson, K.; Palomares, K.J.; Eikey, E.; Schneider, M.; Zheng, K.; Mukamel, D.B.; et al. Facilitators of and barriers to integrating digital mental health into county mental health services: Qualitative interview analyses. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e45718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.M.; Skidmore, S.T.; Akay-Sullivan, S. The influence of trauma symptoms on the therapeutic alliance across treatment. J. Couns. Dev. 2020, 98, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinckrodt, B.; Tekie, Y.T. Revision of the Working Alliance Inventory and Development of a Brief Revised Version Guided by Item Response Theory; Department of Psychology, University of Tennessee: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Källström, M.; Nousiainen, N.; Jern, P.; Nickull, S.; Gunst, A. Mental health among sexual and gender minorities: A Finnish population-based study of anxiety and depression discrepancies between individuals of diverse sexual orientations and gender minorities and the majority population. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matouk, K.M.; Schulman, J.K.; Case, J.A.C. Mental health disparities in sexual minority and transgender women: Implications and considerations for treatment. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 46, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Alvarez, K.; Fillbrunn, M.; Green, J.G.; Jackson, J.S.; Kessler, R.C.; Sadikova, E.; Sampson, N.A.; Vilsaint, C.L.; Williams, D.R.; et al. Racial/ethnic variation in trauma-related psychopathology in the United States: A population-based study. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 2215–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, C.; Ramirez, M.; Mata-Greve, F.; Diaz, A.; Duran, M.C.; Johnson, M.; Grote, N.; Areán, P.A. Acceptability of virtual therapy for postpartum women during COVID-19: A national mixed methods study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 893073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, S.; Lo Coco, G.; Leszcz, M.; Marmarosh, C.L.; Miles, J.R.; Shechtman, Z.; Weber, R.; Tasca, G.A. Therapists’ perceptions of online group therapeutic relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey-based study. Group Dyn-Theor. Res. Pract. 2022, 26, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Batty, G.D.; Pentti, J.; Shipley, M.J.; Sipilä, P.N.; Nyberg, S.T.; Suominen, S.B.; Oksanen, T.; Stenholm, S.; Virtanen, M.; et al. Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: A multi-cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e140–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AQMH Dimension | p-Value | z-Score | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of Use | 0.201 | −1.279 | −0.386 |

| Convenience | 0.011 * | −2.536 | −0.765 |

| Acceptability | 0.109 | −1.604 | −0.484 |

| Practicality | 0.011 * | −2.539 | −0.767 |

| Accessibility | 0.012 * | −2.527 | −0.762 |

| Appropriateness | 0.131 | −1.511 | −0.456 |

| Effectiveness | 0.18 | −1.342 | −0.405 |

| Efficiency | 0.014 * | −2.546 | −0.768 |

| Safety | 0.44 | −0.679 | −0.205 |

| Fit | 0.109 | −1.342 | −0.405 |

| UTAUT Dimension | p-Value | z-Score | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | 0.011 * | 2.546 | 0.768 |

| Effort Expectancy | 0.032 | 2.140 | 0.645 |

| Social Influence | 0.67 | −0.426 | −0.128 |

| Facilitating Conditions | 0.368 | 0.900 | 0.271 |

| Behavioral Intention | 0.057 | 1.904 | 0.574 |

| Use Behavior | 0.182 | 1.335 | 0.403 |

| Theme | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| Creating Connection While Online | Feeling ready to engage with digitally delivered psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations aided in developing a strong therapeutic alliance with their clinician, improving participants’ therapeutic experience. |

| Improved Access to Care | Client participants agreed that the most crucial benefit of digital delivery was that it increased the accessibility of psychotherapies utilized for trauma-affected populations. |

| Differing Experiences Working Digitally | Some participants felt that receiving digitally delivered care made them less anxious than receiving in-person care, while others felt that receiving digitally delivered care made it more difficult to engage with therapy. |

| Difficulties with Working Digitally | Participants raised concerns regarding accessing resources required to attend digitally delivered sessions and worries about their security and privacy while using DMHI. |

| Continuing to Improve Access to Care | Participants provided several recommendations for integrating digital delivery into psychotherapy care for trauma-affected populations, including the expansion of hybrid care. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yap, S.; Allen, R.R.; Bright, K.S.; Brown, M.R.G.; Burback, L.; Hayward, J.; Winkler, O.; Wells, K.; Jones, C.; Sevigny, P.R.; et al. Pilot Study Exploring the Perspectives of Canadian Clients Who Received Digitally Delivered Psychotherapies Utilized for Trauma-Affected Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020220

Yap S, Allen RR, Bright KS, Brown MRG, Burback L, Hayward J, Winkler O, Wells K, Jones C, Sevigny PR, et al. Pilot Study Exploring the Perspectives of Canadian Clients Who Received Digitally Delivered Psychotherapies Utilized for Trauma-Affected Populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020220

Chicago/Turabian StyleYap, Sidney, Rashell R. Allen, Katherine S. Bright, Matthew R. G. Brown, Lisa Burback, Jake Hayward, Olga Winkler, Kristopher Wells, Chelsea Jones, Phillip R. Sevigny, and et al. 2025. "Pilot Study Exploring the Perspectives of Canadian Clients Who Received Digitally Delivered Psychotherapies Utilized for Trauma-Affected Populations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020220

APA StyleYap, S., Allen, R. R., Bright, K. S., Brown, M. R. G., Burback, L., Hayward, J., Winkler, O., Wells, K., Jones, C., Sevigny, P. R., McElheran, M., Zukiwski, K., Greenshaw, A. J., & Brémault-Phillips, S. (2025). Pilot Study Exploring the Perspectives of Canadian Clients Who Received Digitally Delivered Psychotherapies Utilized for Trauma-Affected Populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020220