Surveys of Knowledge and Awareness of Plastic Pollution and Risk Reduction Behavior in the General Population: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Identify validated and generalizable survey instruments;

- -

- Analyze the content of the questions used by these surveys, categorize them into themes, and highlight any shortcomings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Study Eligibility

2.1.2. Population Eligibility

2.2. Search Strategy and Literature Selection

2.3. Thematic Areas

2.3.1. Level of Knowledge About Different Types of Plastics

2.3.2. Level of Knowledge of the Risks Associated with Plastic Pollution

2.3.3. Awareness of Actions to Reduce Potential Harm

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.4.1. Quality Evaluation Tool

2.4.2. Critical Appraisal of Study Quality

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Data Synthesis

3. Results

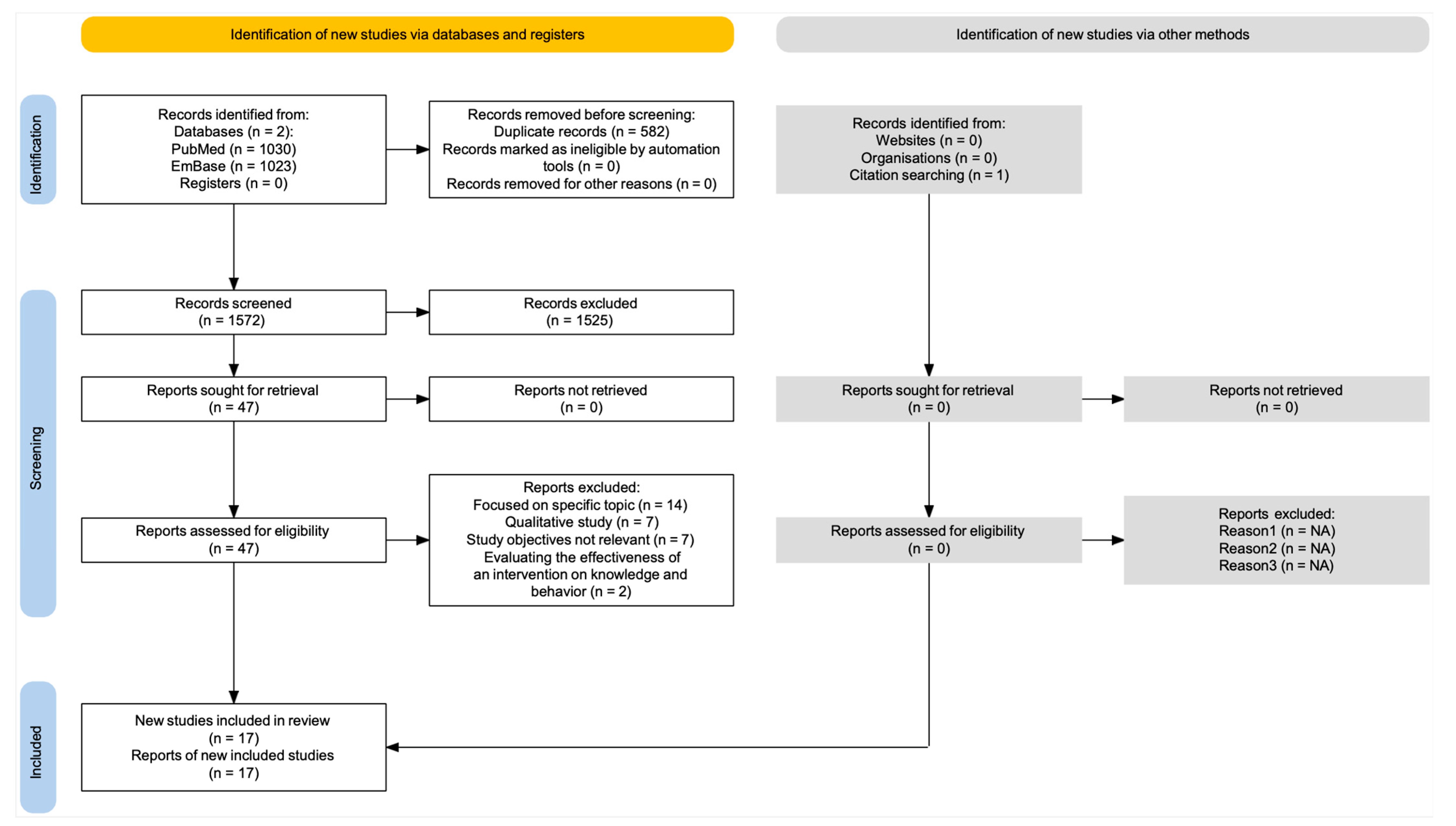

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Design and Participant Characteristics

3.3. Main Thematic Areas

3.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millican, J.M.; Agarwal, S. Plastic Pollution: A Material Problem? Macromolecules 2021, 54, 4455–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, K.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Negrei, C.; Moroșan, E.; Drăgănescu, D.; Preda, O.-T. Microplastics: A Real Global Threat for Environment and Food Safety: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rist, S.; Almroth, B.C.; Hartmann, N.B.; Karlsson, T.M. A critical perspective on early communications concerning human health aspects of microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seewoo, B.J.; Goodes, L.M.; Thomas, K.V.; Rauert, C.; Elagali, A.; Ponsonby, A.-L.; Symeonides, C.; Dunlop, S.A. How do plastics, including microplastics and plastic-associated chemicals, affect human health? Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3036–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.A. Five Misperceptions Surrounding the Environmental Impacts of Single-Use Plastic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14143–14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Raps, H.; Cropper, M.; Bald, C.; Brunner, M.; Canonizado, E.M.; Charles, D.; Chiles, T.C.; Donohue, M.J.; Enck, J.; et al. The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health. Ann. Glob. Health 2023, 89, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. Key Human Rights Considerations for the Negotiations to Develop an International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution. Published online 30 November 2022. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/climatechange/2022-12-01/OHCHR-inputs-INC1.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Hoang, T.C. Plastic pollution: Where are we regarding research and risk assessment in support of management and regulation? Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2022, 18, 851–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewika, M.; Markandan, K.; Ruwaida, J.N.; Sara, Y.; Deb, A.; Irfan, N.A.; Khalid, M. Integrating the quintuple helix approach into atmospheric microplastics management policies for planetary health preservation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felipe-Rodriguez, M.; Böhm, G.; Doran, R. What does the public think about microplastics? Insights from an empirical analysis of mental models elicited through free associations. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 920454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, L.; Green, C. Making sense of microplastics? Public understandings of plastic pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 152, 110908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazzi, L.; Loiselle, S.; Anderson, L.G.; Rocliffe, S.; Winton, D.J. Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BioPlast4Safe. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/en/projects/environment-and-health/bioplast4safe (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayyan–Intelligent Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Aubin, S.; Beaugrand, J.; Berteloot, M.; Boutrou, R.; Buche, P.; Gontard, N.; Guillard, V. Plastics in a circular economy: Mitigating the ambiguity of widely-used terms from stakeholders consultation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 134, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.; Sharma, S.; Gupta, S.; Ghosal, A.; Nadda, A.K.; Jose, R.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, P.; Raizada, P. Prevalence and implications of microplastics in potable water system: An update. Chemosphere 2023, 317, 137848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oludoye, O.O.; Supakata, N. Breaking the plastic habit: Drivers of single-use plastic reduction among Thai university students. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevethan, R. Deconstructing and Assessing Knowledge and Awareness in Public Health Research. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, K.E.; Kho, M.E. How to assess a survey report: A guide for readers and peer reviewers. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2015, 187, E198–E205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolonen, H.M.; Falck, J.; Kurki, P.; Ruokoniemi, P.; Hämeen-Anttila, K.; Shermock, K.M.; Airaksinen, M. Is There Any Research Evidence Beyond Surveys and Opinion Polls on Automatic Substitution of Biological Medicines? A Systematic Review. BioDrugs 2021, 35, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbir, J.; Filho, W.L.; Salvia, A.L.; Fendt, M.T.C.; Babaganov, R.; Albertini, M.C.; Bonoli, A.; Lackner, M.; de Quevedo, D.M. Assessing the Levels of Awareness among European Citizens about the Direct and Indirect Impacts of Plastics on Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammalleri, V.; Marotta, D.; Antonucci, A.; Protano, C.; Fara, G.M. A survey on knowledge and awareness on the issue “microplastics”: A pilot study on a sample of future public health professionals. Ann. Ig. 2020, 32, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitou, A.; Aga-Spyridopoulou, R.N.; Mylona, Z.; Beck, R.; McLellan, F.; Addamo, A.M. Investigating the knowledge and attitude of the Greek public towards marine plastic pollution and the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 166, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagiliūtė, R.; Žaltauskaitė, J.; Sujetovienė, G. Self-reported behaviours and measures related to plastic waste reduction: European citizens’ perspective. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Cai, L.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Che, Y. Public attitudes towards microplastics: Perceptions, behaviors and policy implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.S.; Pratt, S.; Laycock, B.; Ashworth, P.; Lant, P.A. Public attitudes towards plastics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 147, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.; Ashworth, P.; Laycock, B.; Pratt, S.; Lant, P. Public attitudes towards bioplastics—Knowledge, perception and end-of-life management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 1044–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Salvia, A.L.; Bonoli, A.; Saari, U.A.; Voronova, V.; Klõga, M.; Kumbhar, S.S.; Olszewski, K.; De Quevedo, D.M.; Barbir, J. An assessment of attitudes towards plastics and bioplastics in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755 Pt 1, 142732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Barbir, J.; Abubakar, I.R.; Paço, A.; Stasiskiene, Z.; Hornbogen, M.; Fendt, M.T.C.; Voronova, V.; Klõga, M. Consumer attitudes and concerns with bioplastics use: An international study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forleo, M.; Romagnoli, L. Marine plastic litter: Public perceptions and opinions in Italy. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 165, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vazquez, E.; Garcia-Ael, C.; Mesa, M.L.C.; Rodriguez, N.; Dopico, E. Greater willingness to reduce microplastics consumption in Mexico than in Spain supports the importance of legislation on the use of plastics. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1027336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Saechang, O. Is Female a More Pro-Environmental Gender? Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.; Brom, J.; Heidbreder, L.M. Explicitly and implicitly measured valence and risk attitudes towards plastic packaging, plastic waste, and microplastic in a German sample. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1422–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, I.; Santos, A.; Venâncio, C.; Oliveira, M. Knowledge, concerns and attitudes towards plastic pollution: An empirical study of public perceptions in Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleksiuk, K.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Wypych-Ślusarska, A.; Głogowska-Ligus, J.; Spychała, A.; Słowiński, J. Microplastic in Food and Water: Current Knowledge and Awareness of Consumers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.; Miguel, I.; Venâncio, C.; Lopes, I.; Oliveira, M. Public views on plastic pollution: Knowledge, perceived impacts, and pro-environmental behaviours. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, C.J.; Hudson, M.D. Uncertainty about the risks associated with microplastics among lay and topic-experienced respondents. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurobarometer 92.4 (2019) GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. Available online: https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA7602?doi=10.4232/1.13652 (accessed on 21 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yoon, A.; Jeong, D.; Chon, J. The impact of the perceived risk and conservation commitment of marine microplastics on tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 144782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 44 Minton, A.P.; Rose, R.L. The effects of environmental concern on environmentally friendly consumer behavior: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y. Plastic bag usage and the policies: A case study of China. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y. Consumers’ Intention to Bring a Reusable Bag for Shopping in China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reja, U.; Manfreda, K.L.; Hlebec, V.; Vehovar, V. Open-ended vs. close ended questions in web questionnaires. Dev. Appl. Stat. 2003, 19, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Siefer, P.; Neaman, A.; Salgado, E.; Celis-Diez, J.; Otto, S. Human-environment system knowledge: A correlate of pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15510–15526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor Desai, S.; Reimers, S. Comparing the use of open and closed questions for web-based measures of the continued-influence effect. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 51, 1426–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyerl, K.; Putz, O.; Breckwoldt, A. The role of perceptions for community-based marine resource management. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulnayagam, A. Public perception towards plastic pollution in the marine ecosystems of Sri Lanka. Am. J. Mar. Sci. 2020, 8, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, B.L.; Pahl, S.; Veiga, J.M.; Vlachogianni, T.; Vasconcelos, L.; Maes, T.; Thompson, R.C. Exploring public views on marine litter in Europe: Perceived causes, consequences and pathways to change. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpinski, A.; Steinman, R.B. The single category implicit association test as a measure of implicit social cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, P.M.; de la Garza González, A.; Isolde Hedlefs, M. Implicit measures of environmental attitudes: A comparative study. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2016, 9, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.; Reese, G. Implicit associations with nature and urban environments: Effects of lower-level processed image properties. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, E.J.; Halden, R.U. Plastics and environmental health: The road ahead. Rev. Environ. Health 2013, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proshad, R.; Kormoker, T.; Islam, M.; Haque, M.; Rahman, M.; Mithu, M. Toxic effects of plastic on human health and environment: A consequences of health risk assessment in Bangladesh. Int. J. Health 2018, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, R.H.; Harris, R.M.; Mitchell, S.C. Plastic contamination of the food chain: A threat to human health? Maturitas 2018, 115, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azoulay, D.; Villa, P.; Arellano, Y.; Gordon, M.F.; Moon, D.; Miller, K.A.; Thompson, K. Plastic & Health: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet. CIEL 2019. Available online: https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Plastic-and-Health-The-Hidden-Costs-of-a-Plastic-Planet-February-2019.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Luo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Shen, M.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, Z.; Jin, Y. Maternal exposure to different sizes of polystyrene microplastics during gestation causes metabolic disorders in their offspring. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. The plastic in Microplastics: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, N.B.; Hüffer, T.; Thompson, R.C.; Hassellöv, M.; Verschoor, A.; Daugaard, A.E.; Rist, S.; Karlsson, T.; Brennholt, N.; Cole, M.; et al. Are We Speaking the Same Language? Recommendations for a Definition and Categorization Framework for Plastic Debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Chen, L.; Shao, L.; Zhang, H.; Lü, F. Municipal solid waste (MSW) landfill: A source of microplastics? evidence of microplastics in landfill leachate. Water Res. 2019, 159, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rillig, M.C.; Lehmann, A.; de Souza Machado, A.A.; Yang, G. Microplastic effects on plants. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Rocha International. Education. Microplastics Toolbox. Available online: https://arocha.org/en/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- OECD. Greening Household Behaviour: Overview From the 2011 Survey—Revised Edition. OECD Publishing. 2014. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/greening-household-behaviour_9789264181373-en.html (accessed on 11 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 468: Attitudes of European Citizens Towards the Environment. 2017. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/euodp/data/dataset/S2156_88_1_468_ENG (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Department of Environment and Conservation NSW. 2017; Who Cares About the Environment? A Survey of the Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours of People in New South Wales in 2015. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/communities/10533WC09Seminar.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Sharma, A.; Duc, N.T.M.; Thang, T.L.L.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marušić, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Kalvapudi, S.; Muppidi, V.; Ajith, K.; Dutt, A.; Madhugiri, V.S. A survey of surveys: An evaluation of the quality of published surveys in neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir. 2024, 166, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffett, M.; Burns, K.E.; Adhikari, N.K.; Arnold, D.M.; Lauzier, F.; Kho, M.E.; Meade, M.O.; Hayani, O.; Koo, K.; Choong, K.; et al. Quality of reporting of surveys in critical care journals: A methodologic review. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.H.-T.; Thomas, S.M.; Farag, A.; Duffett, M.; Garg, A.X.; Naylor, K.L. Quality of survey reporting in nephrology journals: A methodologic review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 2089–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.B.; Dunbar, N.M.; Tinmouth, A.; Apelseth, T.O.; Lozano, M.; Cohn, C.S.; Stanworth, S.J.; on behalf of the Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST). Collaborative A methodological review of the quality of reporting of surveys in transfusion medicine. Transfusion 2018, 58, 2720–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcopulos, B.A.; Guterbock, T.M.; Matusz, E.F. Survey research in neuropsychology: A systematic review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 34, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. # | First Author | Year of Publication | Objective of Study | Country | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Number of Respondents/Sample Size | Sampling Technique | Administration | Reference of Tool Development | Key Instrument Characteristics |

| [38] | Miguel I | 2024 | (i) To clarify the factors underlying environmental consciousness, concerns, and behaviors; (ii) to assess how participants’ sociodemographic characteristics affect these perceptions, in order to tailor more specific initiatives aimed at increasing environmental knowledge and encouraging pro-environmental behavior. | Portugal | General public (recruitment method is unclear and no specific criteria are indicated) | Not indicated | 1129/NA | Not indicated | Self-administration (hard copy) | Not indicated | 13 questions. Response collection: five-point Likert scale. To ensure face validity, the questionnaire was previously submitted to a pilot study to identify potential weaknesses of the questionnaire and test if the questions were formulated in a clear and understandable way. The feedback from the 5 subjects participating in the pilot study was discussed and considered for the final version. |

| [28] | Dagiliūt R | 2023 | To analyse the self-reported actions related to reduction of plastic and MP pollution by Europeans and factors influencing actions undertaken. | European Union | General public (recruitment method is unclear and no specific criteria are indicated) | Not indicated | 27,083/27,498 (98.5%) | The Eurobarometer datasets provide for two types ofweighting, a post-stratification weighting and a population size weighting. | Face-to-face interviews | [42] | 11 questions. Response collection: dichotomous responses; 4-point Likert scale. The study used the Eurobarometer survey on environmental attitudes, which is not intended for plastic pollution directly. The validity and reliability of scales was tested using Cronbach’s α. This coefficient for all scales ranges between 0.526 and 0.771, indicating moderate reliability of the scales. |

| [35] | Garcia-Vazquez E | 2022 | To determine the differences between Mexico and Spain in terms of behavior and behavioral intentions regarding MP. | Spain, Mexico | University students in Spain and Mexico | Not indicated | 572/NA | Snowball methodology | Self-administration (online) | [29,43] | 13 questions. Response collection: multiple choice; 7-point Likert scale. The questionnaire was developed based on previously published tools and examined by a panel of 6 experts. The Content Validity Index obtained from the expert panel was 0.96. The internal consistency was measured based on Cronbach’s α values (0.94 for items measuring MP risk awareness). |

| [39] | Oleksiuk K | 2022 | To research the current knowledge and awareness of consumers regarding sources, exposure, and health hazards connected to microplastics’ presence in water and foods, especially their impact on internal organs, metabolic processes, and reproductive functions. | Poland | In order to take part in the questionnaire survey, it was required to be aged 18 or above, live in Silesia (Poland), and be a student. | Not indicated | 410/NA | Snowball methodology | Computer-aided web interview, via Google Forms | Not indicated | 26 questions. Response collection: single and multiple choice. The questionnaire was validated for reliability, correctness, and relevance. Repeatability of the responses was examined by distributing the questionnaire twice to a random sample of 20 people. A total of 78.3% of the questions obtained very good agreement; Kappa > 0.75. |

| [36] | Li Y | 2022 | To determine whether there are gender differences in people’s pro-environmental psychology and behaviors in China. | China | No specific criteria are indicated. Recruitment of respondents was completed through social media platforms utilizing preexisting social and personal contacts. | Not indicated | 532/NA | Snowball methodology | Self-administration (online) | [44,45,46] | 7 questions: four kinds of pro-environmental psychology questions and three for pro-environmental behaviors. Response collection: 5-point Likert scale; dichotomous responses. The questionnaire was pilot tested on 25 respondents to revise the wording of the survey items so that the statements were appropriate. |

| [33] | Filho WL | 2022 | To explore the level of awareness and attitudes about bioplastics | 42 countries located mostly in Europe and Asia | No specific criteria are indicated. Using the LimeSurvey platform, the questionnaire was made available electronically in several countries for five months. | Not indicated | 384/NA | Using the LimeSurvey platform, the questionnaire was made available electronically in several countries for five months. | Self-administration (online) | Not indicated | 19 questions. Response collection: multiple choice; 4-point Likert scale. Pre-testing by a subset of the respondents was carried out to identify and mitigate language and understanding problems. |

| [32] | Filho WL | 2021 | To investigate some of the main trends in plastic consumption, hence offering a better understanding of the effects of plastic pollution on the environment and the problems related to plastic use as perceived by consumers. Furthermore, the extent of current efforts on how to reduce plastic consumption was assessed. Special attention was paid to an analysis of the awareness of citizens of bioplastics, their usage, and environmental impacts. | 16 European countries | No specific criteria are indicated. The survey was disseminated to all partners of the Horizon 2020 project BIO-PLASTICS EUROPE and in European JISCMail mailing lists related to sustainability and sustainable consumption. | Not indicated | 127/NA | The survey was disseminated to all partners of the Horizon 2020 project BIO-PLASTICS EUROPE. Additionally, the survey was also disseminated in European JISCMail mailing lists related to sustainability and sustainable consumption. The link remained active during February and March of 2020 and received 127 responses from 16 European countries. | Self-administration (online) | Not indicated | 18 questions. Response collection: 5-point Likert Scale. The questionnaire was pre-tested by partners of the BIO-PLASTICS EUROPE project. |

| [40] | Soares J | 2021 | To analyze perceptions about plastic pollution and its impacts as well as sociodemographic and psychological factors predicting individuals’ pro-environmental behaviors in the Portuguese context. | Portugal | Adults (aged 18 or older) | Not indicated | 428/NA | The link to the questionnaire was disseminated by email and social/personal networks to achieve a wider and varied sample. | Self-administration (online) | Not indicated | 50 questions, divided into 4 sections. A Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), was used to assess the level of agreement with each item. Before the general administration of the questionnaire, a pre-test was conducted, to identify potential weaknesses of the questionnaire and appropriately formulate the questions in a clear and understandable way. The feedback from a sample of 5 subjects was discussed and considered for the final version of the questionnaire. |

| [27] | Charitou A | 2021 | Exploring knowledge and attitudes toward marine plastic pollution and the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive | Greece | The questionnaire was boosted via social media advertising without restrictions or focus to social media users with particular characteristics, only targeting profiles with Greek Internet Protocol addresses (IPs), in order to limit the bias of the sample. In addition, through the snowball method, participants were also asked to distribute it by their social media too. | No restriction | 374/NA | Snowball methodology | Self-administration (online) | [47,48,49] | 14 questions. Response collection: open-ended and multiple choice. structured questionnaire developed specifically for this study in Greek. |

| [34] | Forleo MB | 2021 | (i) to identify homogeneous segments of people according to the importance they attach to different sources and impacts of plastic litter; (ii) to understand if behavioral aspects and personal characteristics emerged for each cluster of people. | Italy | No specific criteria are indicated: respondents were invited to take part in the survey and asked to send a questionnaire to link their acquaintances, in order to reach a wider and varied sample | Not indicated | 605/NA | Snowball methodology | Self-administration (online) | [50,51,52] | 8 questions. Response collection: 4-point Likert scale; multiple choice. The selection of variables was inspired by several studies. Pilot testing by ten respondents was performed to check comprehension. |

| [37] | Menzel C | 2021 | To systematically investigate valence- and risk-related attitudes towards plastic packaging, plastic waste, and microplastic. | Germany | No specific criteria are indicated. | Not indicated | 212/NA | Participants were recruited via university email lists, social media, and a flyer at university facilities. | Self-administration (online, single-category implicit association test (SC-IAT) | [53,54,55] | The survey first required participants to respond to stimuli (words and images), and then to answer 12 questions on 5-point Likert scales. |

| [41] | Thiele CJ | 2021 | What is the level of concern about microplastics in relation to other environmental issues? What are the reasons for concern about microplastics? How do people perceive the hazardousness of microplastics? And do concern levels and hazardousness perception differ between lay people and people academically or professionally versed in the topic? | Multiple countries | 18 or older | Not indicated | 1681/NA | Snowball methodology | Self-administration (online) | Not indicated | 13 questions. Response collection: single and multiple choice, Likert scale. A survey was designed in English and translated into Spanish, German, Italian, French, Polish, Greek, Croatian, Japanese, Thai, Indonesian, Malay, Portuguese, Chinese, and Arabic. Back-translation via Google Translate was performed. |

| [25] | Barbir J | 2021 | To assess European citizens’ perspectives regarding their plastic consumption, and to evaluate their awareness of the direct and indirect effects of plastics on human health in order to influence current behavior trends. | 25 European countries | No specific criteria are indicated. The survey was distributed through faculty and scientific mailing lists related to sustainability. | No restriction | 1000/NA | The survey was distributed through faculty and scientific mailing lists related to sustainability. | Self-administration (online) | [56,57,58,59,60] | 20 questions. Response collection: 5-point Likert scale; multiple choice. Pre-testing was carried out to adjust for conciseness and clarity. |

| [26] | Cammalleri V | 2020 | To assess the level of knowledge and awareness of medical students and residents in public health with regard to the theme “microplastics pollution”, in order to evaluate their competence in such a problem and to evidence possible needs for information, training. and updating the future leading figures in Public Health. | Italy | Undergraduate or postgraduate students attending Public Health university courses at the Sapienza University of Rome | Not indicated | 151/NA | The research project was presented to the Presidents of the selected university degree courses, who organized the meetings with the students. The project was explained to all the students in the classroom. | Self-administration (mode unclear) | [61,62,63,64,65] | 13 questions. Response collection: ordinal scale; multiple choice. The questionnaire was elaborated ad hoc on the basis of scientific evidence and of an educational project on microplastics, and validated before the beginning of the study. |

| [29] | Deng L | 2020 | This study investigated the public’s perceptions and attitudes towards microplastics in Shanghai and used an ordered regression model to explore the public’s willingness to reduce microplastics and its influencing factors. | China | No specific criteria are indicated. Respondents were recruited in parks, subway stations, shopping malls, and other public places in 4 administrative districts of Shanghai and through social media. | Not indicated | 437/480 (91%) | We recruited respondents in parks, subway stations, shopping malls, and other public places in 4 administrative districts of Shanghai and through social media. | Face-to-face interview | Not indicated | 23 questions. Response collection: single and multiple choice. 50 respondents were pre-tested to avoid possible misinterpretations. |

| [31] | Dilkes- Hoffman L | Sept., 2019 | To identify whether the general public views plastics as a serious environmental issue. Secondary aims include to understand what factors influence attitudes toward plastics, and to explore whether those attitudes motivate any personal reduction in plastic use. | Australia | Sample representative of gender, age, and state for the Australian population | Not indicated | 2518/3028 (83.2%) | The market research company selected respondents using the quota method, meaning that the sample selected was representative of gender, age, and state for the Australian population. | Self-administration (email) | [66,67,68] | 10 questions. Response collection: Likert scale, multiple choice and open-ended. The survey was developed based on a variety of periodic environmental surveys, and refined through several rounds of prototyping within the authors’ research groups and selected members of the public. |

| [30] | Dilkes- Hoffman L | May, 2019 | To understand current knowledge and perceptions regarding bioplastics | 8 questions. Response collection: Likert scale, multiple choice and open-ended.The survey was developed based on a variety of periodic environmental surveys, and refined through several rounds of prototyping within the authors’ research groups and selected members of the public. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caminiti, C.; Diodati, F.; Puntoni, M.; Balan, D.; Maglietta, G. Surveys of Knowledge and Awareness of Plastic Pollution and Risk Reduction Behavior in the General Population: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020177

Caminiti C, Diodati F, Puntoni M, Balan D, Maglietta G. Surveys of Knowledge and Awareness of Plastic Pollution and Risk Reduction Behavior in the General Population: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020177

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaminiti, Caterina, Francesca Diodati, Matteo Puntoni, Denisa Balan, and Giuseppe Maglietta. 2025. "Surveys of Knowledge and Awareness of Plastic Pollution and Risk Reduction Behavior in the General Population: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020177

APA StyleCaminiti, C., Diodati, F., Puntoni, M., Balan, D., & Maglietta, G. (2025). Surveys of Knowledge and Awareness of Plastic Pollution and Risk Reduction Behavior in the General Population: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020177