Barriers to and Enablers of Preventive Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Among Women Seeking Asylum in Melbourne, Victoria: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Context

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

2.4. Conceptual Framework

2.5. Data Source

2.6. Reflexivity—Positioning the Researcher

2.7. Data Collection Procedure

2.8. Rigor and Trustworthiness

2.9. Data Management and Analysis

2.10. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

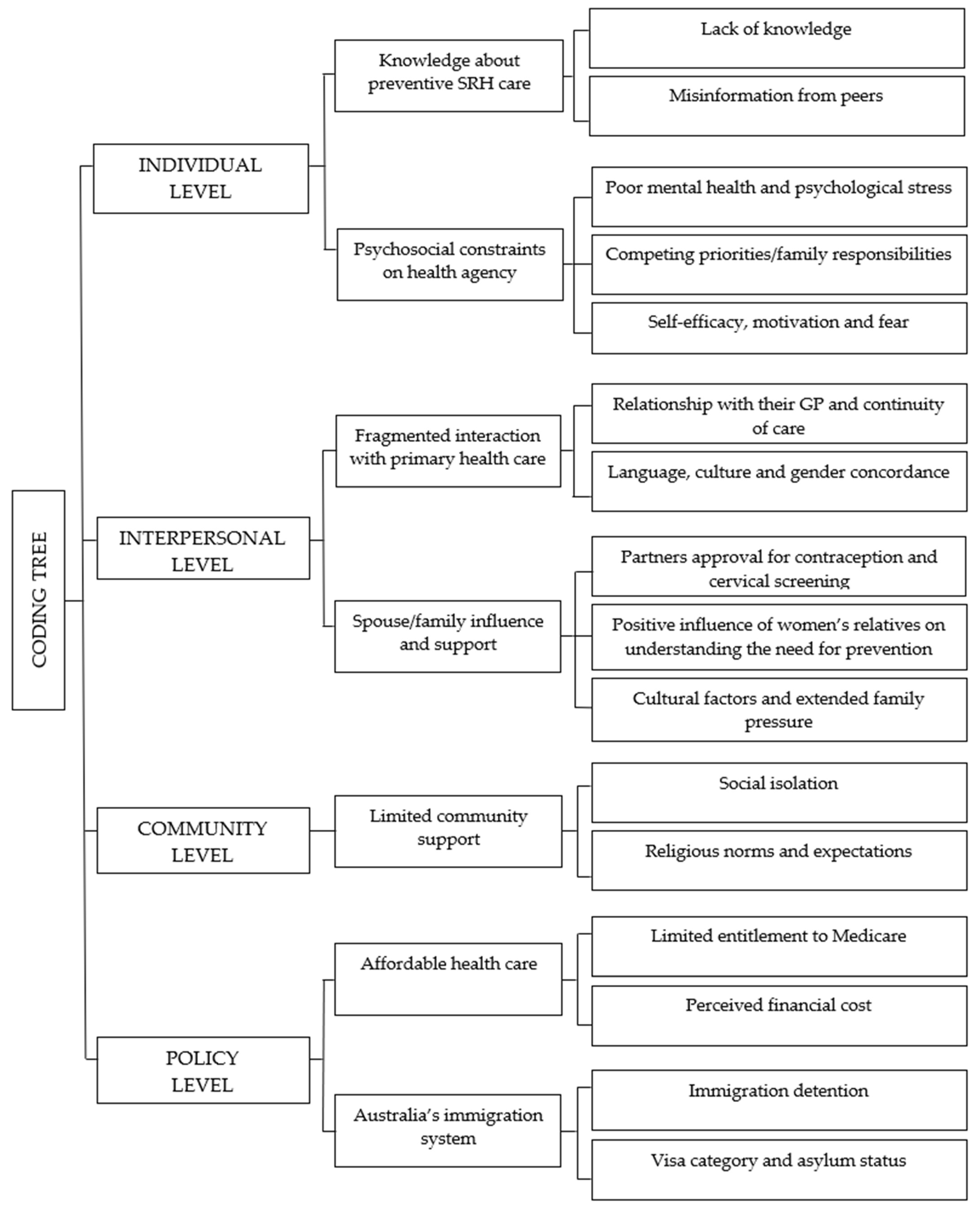

3.2. Levels of Influence

3.3. Individual Level

3.3.1. Lack of Knowledge

“Yes, [cervical] screening is for anyone it gets cancer earlier, we can diagnose with the pap smear or any other kind of vaginal disease or anything from this we can early detect.” [Breast screening] That’s also early screening test for detecting breast cancer that’s a really good opportunity (Shiryani, 46)

“I don’t know anything about contraception, or I didn’t know anything about it back in my home country and I learned about that only after I had the baby, when the baby was 6 weeks old, I had to go and see a GP and that’s the time they asked these questions and talked about contraception, that’s the first time I heard about that before that I didn’t know anything about contraception.” (Vijitha, 34)

“No I don’t know about this [HPV Vaccination]… and I’ve never heard about it in Lebanon.” (Iman, 37)

3.3.2. Misinformation from Peers

“…people [women] that are not aware of what it is and just listening to misinterpretation, for example because some people said that if you take birth control you have cancer,… and like no it doesn’t mean that. Birth control doesn’t do that, it doesn’t cause cancer. It stops you from getting pregnant. So, it’s the misunderstanding and just listening to people that don’t know much about these things and maybe they are just spreading wrong information to others.” (Afidj, 35)

“there are some other cousins or friends who come here and they say they are going for the cervical screen and I asked them what it was all about. Then they said I don’t need to go.” (Vijitha, 28)

“Yes, my sister and my friends all stopped because they are gaining weight so they stopped the implants. And some people are afraid of the IUD because people will get an infection for using IUD so they stop. They are afraid to use it.” (Jen, 34)

3.3.3. Poor Mental Health and Psychological Stress

“…I have seen some people here and back in Iran and I think it [barriers to accessing screening] is linked to their low mood and their mental health. Like they are drowning in their problems, they forget about themselves and they make themselves like the last priority.” (Sarah, 34)

3.3.4. Competing Priorities and Family Responsibilities

“You are struggling getting a job, getting money to live and then you forget about your physical health…the things that you need such as getting a job to live here. And the other thing is asylum seekers with young kids, so who is going to look after your baby if you are working. So, it’s a lot of things to be worried about because they don’t have help with child care.” (Maya, 43)

3.3.5. Self Efficacy, Motivation and Fear

“…I have a friend who simply doesn’t care. She had 4 children, I explained to her that this is very important,…you have to do the papsmear. She said I don’t have patience for this sort of thing…because she is also suffering from depression she just says “I don’t have the patience to go through the process” (Mariam, 43)

“I hate doing it, it’s painful. I don’t like anyone [indicates pelvic area]. [are you mainly scared of the pain?] yes and I’m shy. Because some women tell me it’s painful and I think two and three days there is blood. And I stopped to think for this test.” (Iman 37)

“…some women they feel shame, it’s not a good decision to have someone looking at you and they don’t like to do this they feel common and shame” (Maya, 43)

“I think some people [women seeking asylum in her community] they are scared because if they tested, is it positive. What then? They are scared about the result. That’s why they don’t do go. Because they don’t want to risk it, if it is something that’s wrong or something that happens. What can they do about it.” (Jen, 34)

“[Screening is for] like cancer prevention. Actually, I want to do breast screening to make sure for check. I want to know actually”. (Akgni, 27)

3.4. Interpersonal Level

3.4.1. Importance of the Relationship with Their GP and Continuity of Care

“For some of them [women seeking asylum in her community] maybe a lack of information because I’ve never seen that much talking about contraception in Australia. Even my GP never asked me but after I got my daughter then that doctor asked me are you planning to do any contraception like that, he asked, otherwise no one did ask from me. It’s like a very big secret, like it’s not much sharing information between too many migrant backgrounds.” (Shiryani, 46)

“…I am happy with my GP. She is good she changed she has moved to another clinic so…continuity particularly with a doctor that speaks our language, that’s important. So when they change and we get a doctor that speaks only English so it’s harder to have that relationship”. (Jen, 34)

“Sometimes doctors are not talking about it. I don’t know my GP, a lady doctor but she never asked which kind of contraception…” (Shiryani, 46)

“If it’s meant to be given to them [my children] I will go to my GP who speaks Tamil and I will ask him to explain to me why it’s being given and only after I am understanding that will I give consent.” (Vijitha, 28)

3.4.2. Language, Culture and Gender Concordance

“A female doctor with my language. GP female doctor and gynae doctor who is also the same doctor. [Patients initial GP] He tells me to go to the female doctor she speaks my language, screening also she helped me.” (Maria, 36)

“Yes, it’s kind of like taboo to talk about contraception and sex kind of thing, some of the women don’t like to talk even to their GP, they are very insecure about that…With the GP they are thinking there is not that much connection with the doctor but the nurse they [women] are a little bit closer to them.” (Shiryani, 46)

3.4.3. Partners Approval for Contraception and Cervical Screening

“My side what happened was that bleeding too much, it started but by one year my husband very upset bleeding going on 15 days 20 days normal so he said “OK take it down I don’t want it” [IUD]”. (Maria, 36)

“Sometimes so they’re [women] not caring about their health issues, they are dependent. The husbands don’t see it as important, their wife’s health. I think maybe the GP or something, we have to educate men also as well I think. [Men] don’t know about this kind of [cervical] they don’t know fully.” (Shiryani, 46)

3.4.4. Cultural Factors and Extended Family Pressure

“There is another cultural issue which is extremely important which is the interference of the extended family. [ND can you talk w a bit more about that?] The example is my own life. When I got married I didn’t want to have children right away, I wanted to have a little bit of just knowing my husband or having some fun or just not having children. My husband on the other hand wanted to have children straight away and my mother was saying don’t become pregnant soon, just take your time. His mother was saying when are you going to have the kids. I was not actually confiding to my husband what my mother was saying and he was not confiding to me what his mother was saying but it was unspoken words.” (Sabagie, 34)

3.4.5. Positive Influence of Women’s Relatives on Understanding the Need for Prevention

“That’s to protect myself and the people around me,…I want to protect my family and I get why someone didn’t do it, [vaccination] but yes I think it’s good for my health.” (Akgni, 27)

3.5. Community Level

3.5.1. Social Isolation

“Well um those that want to take it [contraception] is because maybe they have come to 2 or 3 kids now and they don’t want to have anymore. And life is so hard in Australia with children, while back home where I came from I can leave my children with a friend with an Auntie without any problem but here it is not like that. So, you kind of can’t think no I cannot do this here I have to stop.” (Afidji, 35)

“…I came over here when I was only 19 years old…I didn’t come with my parents. If they were here I could have asked my mother… so, I didn’t know what to ask or what to go for. I wouldn’t know [why women don’t do screening] because the women from my community… that I know are much older than me, I’m much younger and I would be reluctant to ask them about whether they would like to do it [cervical screening] or why they are not doing it.” (Vijitha, 28)

“Nobody talks openly about this. I don’t have much friends. We can talk because if I ask the doctor he will tell me but no talk to anyone. I don’t know anyone” (Maria, 36)

3.5.2. Religious Norms and Expectations Shared by the Religious Community

“In my country there are some religious beliefs, it’s a Catholic country and the catholic church say you have to have the kids that God send to you so its another thing more common in the countryside.” (Maya, 43) and this “In my culture they said it is not good to use contraception, that children are a gift from God, that its not good to stop yourself from getting pregnant when you are given the chance to have children.” (Afiji, 35)

3.6. Policy Level

3.6.1. Limited Entitlement to Medicare

“The [Blue] Medicare card is issued to us only for 6 months in a year. So, if we get sick family or I get sick we have to pay and see the doctors or we have to go to emergency. And going to emergency is not a nice experience either. So that’s the problem. We have Medicare only for 6 months in a year.” (Jen, 34)

“Well I didn’t have a Medicare for one year and I was given Medicare only 2 months ago. As I’m on a bridging visa as we are still on a bridging visa so the department of immigration is quite strict and the Medicare used to be valid for one or two years. But they are valid for only 6 months at the moment.” (Sarah, 34) Limited access to health care due to Medicare ineligibility led to out-of-pocket costs and long waiting times for appointments. This was evidenced by women resorting to seeking hospital services instead of more suitable primary care services.

“…after we go to the emergency or something like this, because if you want to see your GP at the ASRC you need an appointment. Some doctors don’t have any [appointments] available sometime a week, two weeks, sometimes a month, so that means we don’t have a choice we need to go to emergency…” (Tiez, 36)

3.6.2. Perceived Financial Cost

“…back home when you go for a test you have to pay out of pocket yourself, yes so its whenever you have money aside to do it then you go and do it but here its every 5 years, so people are not aware of that yes so that people who came here, if I need to go to hospital I need money out of my pocket and if I don’t have it, I can’t do it.” (Afidji, 35)

3.6.3. Immigration Detention

“I just have to tell you that for example when we were in camp there was a talk of sending us to Papua New Guinea [detention] so women were trying very hard to have children, so they would take out the Merina to have children not to be sent there [to PNG].” (Mariam, 43)

3.6.4. Visa Category and Asylum Status

4. Discussion

4.1. Individual-Level Factors

4.2. Interpersonal-Level Factors

4.3. Community-Level Factors

4.4. Policy-Level Factors

| Approaches to Enhancing Access to Preventive Sexual and Reproductive Care for Women Seeking Asylum are Presented for Each Level of the Socioecological Model. It Is Important that Strategies to Enhance Access Occur Across the Range of Levels, with Attention to Maximising Benefits Between the Different Layers of Disadvantage. |

|---|

| Individual level |

|

| Interpersonal level |

|

|

|

|

| Community level |

|

|

|

| Policy level |

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Government. Humanitarian Settlement Program Canberra: Department of Home Affairs. 2024. Available online: https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/settling-in-australia/humanitarian-settlement-program (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Refugee Council of Australia. Australia’s Asylum Policies: RCoA. 2014. Available online: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/asylum-policies/2/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Refugee Council of Australia. Statistics on People Seeking Asylum in the Community: RcoA. 2021. Available online: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/asylum-community/8/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Victoria State Government Department of Health. Refugee and Asylum Seeker Health and Wellbeing: Department of Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/populations/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-health-and-wellbeing (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Ziersch, A.; Miller, E.; Baak, M.; Mwanri, L. Integration and social determinants of health and wellbeing for people from refugee backgrounds resettled in a rural town in South Australia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Due, C.; Ziersch, A. The relationship between employment and health for people from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds: A systematic review of quantitative studies. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 18, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procter, N.G.; Kenny, M.A.; Eaton, H.; Grech, C. Lethal hopelessness: Understanding and responding to asylum seeker distress and mental deterioration. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. The Australian Health System: Department of Health, Disability and Aging. 2025. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/about-us/the-australian-health-system?language=en (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Correa-Velez, I.; Gifford, S.M.; Bice, S.J. Australian health policy on access to medical care for refugees and asylum seekers. Aust. N. Z. Health Policy 2005, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Australia’s Immigration Detention Policy and Practice. 2014. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/projects/6-australias-immigration-detention-policy-and-practice (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Silove, D.; Mares, S. The mental health of asylum seekers in Australia and the role of psychiatrists. BJPsych Int. 2018, 15, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, M.A.; Procter, N.; Grech, C. Mental deterioration of refugees and asylum seekers with uncertain legal status in Australia: Perceptions and responses of legal representatives. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, L. A safe haven? Women’s experiences of violence in Australian immigration detention. Punishm. Soc. 2024, 26, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawyer, F.; Enticott, J.; Block, A.; Cheng, I.; Meadows, G. The mental health status of refugees and asylum seekers attending a refugee health clinic including comparisons with a matched sample of Australian-born residents. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toar, M.; O’Brien, K.; Fahey, T. Comparison of self-reported health & healthcare utilisation between asylum seekers and refugees: An observational study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadgkiss, E.J.; Renzaho, A.M. The physical health status, service utilisation and barriers to accessing care for asylum seekers residing in the community: A systematic review of the literature. Aust. Health Rev. 2014, 38, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posselt, M.; McIntyre, H.; Ngcanga, M.; Lines, T.; Procter, N. The mental health status of asylum seekers in middle- to high-income countries: A synthesis of current global evidence. Br. Med. Bull. 2020, 134, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukčević Marković, M.; Bobić, A.; Živanović, M. The effects of traumatic experiences during transit and pushback on the mental health of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2023, 14, 2163064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.; Alloun, E.; Weber, D.; Smith, M.; Harris, P. “Lived the Pandemic Twice”: A Scoping Review of the Unequal Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Asylum Seekers and Undocumented Migrants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubini, E.; Valente, M.; Trentin, M.; Facci, G.; Ragazzoni, L.; Gino, S. Negative consequences of conflict-related sexual violence on survivors: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, E.; Jaeger, F.; Zemp, E.; Tschudin, S.; Bischoff, A. Reproductive health care for asylum-seeking women—A challenge for health professionals. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.; Assefa, Y. Access to health services among culturally and linguistically diverse populations in the Australian universal health care system: Issues and challenges. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, K.; Stirling-Cameron, E.; Ramos, N.; Martinez SanRoman, I.; Bojorquez, I.; Spata, A.; Baltazar Lujano, B.; Goldenberg, S. “When you leave your country, this is what you’re in for”: Experiences of structural, legal, and gender-based violence among asylum-seeking women at the Mexico-U.S. border. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spike, E.; Smith, M.; Harris, M. Access to primary health care services by community-based asylum seekers. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 195, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengesha, Z.; Weber, D.; Smith, M.; Harris, P.; Haigh, F. ‘Fragmented care’: Asylum seekers’ experience of accessing health care in NSW. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fair, G.L.; Harris, M.F.; Smith, M.M. Transition from an asylum seeker-specific health service to mainstream primary care for community-based asylum seekers: A qualitative interview study. Public Health Res. Pract. 2018, 28, e2811805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Fam. Med. Community Health 2019, 7, e000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Cultural diversity: Census: ABS. 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/cultural-diversity-census/latest-release (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- McLeroy, K.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ. Behav. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, S.; Earp, J. Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts: Twenty Years of “Health Education & Behavior” Health Promotion Interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, N.; Hammarberg, K.; Romero, L.; Fisher, J. Access to preventive sexual and reproductive health care for women from refugee-like backgrounds: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, D.G.R. Researcher Positionality—A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research—A New Researcher Guide. Int. J. Educ. 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters. Australia’s National Standards and Certifying Authority for Translators & Interpreters: NAATI. 2000. Available online: https://www.naati.com.au/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. Demystification and Actualisation of Data Saturation in Qualitative Research Through Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2024, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.B.; Dune, T.; Perz, J. Culturally and linguistically diverse women. Sex. Health 2016, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, K.; Msowoya, U.; Burduladze, N.; Salsberg, J.; MacFarlane, A.; Dore, L.; Gilfoyle, M. Antecedents and consequences of health literacy among refugees and migrants during the first two years of COVID-19: A scoping review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silove, D.; Ventevogel, P.; Rees, S. The contemporary refugee crisis: An overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.B.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Challenges in the Provision of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Refugee and Migrant Women: A Q Methodological Study of Health Professional Perspectives. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Chan, W.; Spitz, A. Pathways to Sexual Health Among Refugee Young Women: A Contextual Approach. Sex. Cult. 2021, 25, 1789–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohit, N.F.M.; Haque, M. Forbidden Conversations: A Comprehensive Exploration of Taboos in Sexual and Reproductive Health. Curēus 2024, 16, e66723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanlawon, K.; Reeves, M.; Agbaje, O.F. Contraceptive use: Knowledge, perceptions and attitudes of refugee youths in Oru refugee camp, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2010, 14, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, T.; Zimet, G.; Rosenthal, S.; Morrow, C.; Ding, L.; Huang, B.; Kahn, J. Human papillomavirus vaccine-related risk perceptions and subsequent sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted infections among vaccinated adolescent women. Vaccine 2016, 34, 4040–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.E.; Davidson, G.R.; Schweitzer, R.D. Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: Best practices and recommendations. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C.; Gifford, S. “It is Good to Know Now…Before it’s Too Late”: Promoting Sexual Health Literacy Amongst Resettled Young People With Refugee Backgrounds. Sex. Cult. 2009, 13, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botfield, J.R.; Newman, C.E.; Kang, M.; Zwi, A.B. Talking to migrant and refugee young people about sexual health in general practice. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, E.; Davis, E.; Gibbs, L.; Block, K.; Szwarc, J.; Casey, S.; Duell-Piening, P.; Waters, E. Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: Reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrio-Ruiz, C.; Ruiz de Vinaspre-Hernandez, R.; Colaceci, S.; Juarez-Vela, R.; Santolalla-Arnedo, I.; Durante, A.; Di Nitto, M. Language and Cultural Barriers and Facilitators of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care for Migrant Women in High-Income European Countries: An Integrative Review. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2024, 69, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C.; Gifford, S. Narratives of sexual health risk and protection amongst young people from refugee backgrounds in Melbourne, Australia. Cult. Health Sex. 2010, 12, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aibangbee, M.; Micheal, S.; Liamputtong, P.; Pithavadian, R.; Hossain, S.; Mpofu, E.; Dune, T. Socioecologies in shaping migrants and refugee youths’ sexual and reproductive health and rights: A participatory action research study. Reprod. Health 2024, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirling-Cameron, E.; Almukhaini, S.; Dol, J.; DuPlessis, B.; Stone, K.; Aston, M.; Goldenberg, S. Access and use of sexual and reproductive health services among asylum-seeking and refugee women in high-income countries: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawadogo, P.; Sia, D.; Onadja, Y.; Beogo, I.; Sangli, G.; Sawadogo, N.; Gnambani, A.; Bassinga, G.; Robins, S.; Nguemeleu, E. Barriers and facilitators of access to sexual and reproductive health services among migrant, internally displaced, asylum seeking and refugee women: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahid, H.; Sebbani, M.; Cherkaoui, M.; Amine, M.; Adarmouch, L. The influence of gender norms on women’s sexual and reproductive health outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qutranji, L.; Silahli, N.Y.; Baris, H.E.; Boran, P. Refugee women’s well-being, needs and challenges: Implications for health policymakers. J. Public Health 2020, 42, e506–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.M.; Schmitt, M.E.; Adebayo, C.T.; Weitzel, J.; Olukotun, O.; Christensen, A.M.; Ruiz, A.M.; Gilman, K.; Quigley, K.; Dressel, A.; et al. Promoting the health of refugee women: A scoping literature review incorporating the social ecological model. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, K.S.; Pottie, K.; Kim, I.; Kim, W.; Lin, L. Strengthening effective preventive services for refugee populations: Toward communities of solution. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Walpola, R.; Harris-Roxas, B.; Li, J.; Mears, S.; Hall, J.; Harrison, R. Improving primary health care quality for refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review of interventional approaches. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2022, 25, 2065–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Tomkow, L.; Farrington, R. Access to primary health care for asylum seekers and refugees: A qualitative study of service user experiences in the UK. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 69, e537–e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishehgar, S.; Gholizadeh, L.; DiGiacomo, M.; Green, A.; Davidson, P.M. Health and Socio-Cultural Experiences of Refugee Women: An Integrative Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, C.; Frost, R.; Sherwood, L.; Shevlin, M.; Hyland, P.; Halpin, R.; Murphy, J.; Silove, D. Post-migration factors and mental health outcomes in asylum-seeking and refugee populations: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1793567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Werthern, M.; Robjant, K.; Chui, Z.; Schon, R.; Ottisova, L.; Mason, C.; Katona, C. The impact of immigration detention on mental health: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timlin, M.; Russo, A.; McBride, J. Building capacity in primary health care to respond to the needs of asylum seekers and refugees in Melbourne, Australia: The ‘GP Engagement’ initiative. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2020, 26, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorian State Government Department of Health. Hospital Access for People Seeking Asylum. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/hospital-access-for-people-seeking-asylum (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Squires, A. Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: A research review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP): Department of Home Affairs. 2025. Available online: https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/settling-in-australia/amep/about-the-program (accessed on 24 July 2025).

| Women (n = 12) | |

|---|---|

| Country of birth | |

| Iran | 3 |

| Sri Lanka | 3 |

| Colombia, Indonesia, Lebanon, Malaysia, Togo and Pakistan | 6 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 11 |

| Widowed | 1 |

| Maternal status | |

| Have children | 11 |

| Have no children | 1 |

| Level of completed education | |

| Secondary education (Year 9 or above) | 7 |

| Tertiary/university | 5 |

| Employment | |

| Home duties | 10 |

| Employed | 2 |

| Years in Australia | |

| 1–5 | 3 |

| 6–10 | 8 |

| 11–15 | 1 |

| Time in immigration detention | |

| Yes (2 to 6 months) | 5 |

| No | 7 |

| Participants (Pseudonym) | Age (Years) | Years in Australia | Region of Origin | Occupation | Level of Education Completed | Immigration Detention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afidj | 35 | 6 | West Africa | Home duties | Year 12/University | No immigration detention, arrived on a tourist visa |

| Maria | 36 | 3 | South Asia | Home duties | Year 12 | No immigration detention, arrived on a tourist visa |

| Maya | 43 | 4 | South America | Medical doctor | University level | No immigration detention, arrived on a tourist visa |

| Sarah | 34 | 9 | Middle East | Home duties | Year 10 | 3 months—detention centre |

| Shiryani | 46 | 14 | South Asia | Home duties | University level | No detention following Ministerial Intervention |

| Mariam | 43 | 10 | Middle East | Home duties | Year 9 | 2 months—Christmas Island detention 2 months—Perth detention centre |

| Sabagie | 34 | 9 | Middle East | Home duties | University level | 3 months—Darwin detention centre |

| Tiez | 36 | 8 | Southeast Asia | Home duties | Year 12 | No immigration detention, arrived on a tourist visa |

| Akgni | 27 | 2 | Southeast Asia | Home duties | Year 10 | No immigration detention, arrived on a tourist visa |

| Iman | 37 | 10 | Middle East | Home duties | University level | No immigration detention, arrived on a tourist visa |

| Vijitha | 28 | 9 | South Asia | Home duties | Year 11 | 3 months—Christmas Island detention, 6 weeks—Darwin detention centre |

| Jen | 34 | 9 | South Asia | Elderly care/personal carer | Year 12 | 3 months—Christmas Island detention, 6 weeks—Darwin detention centre |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davidson, N.; Hammarberg, K.; Fisher, J. Barriers to and Enablers of Preventive Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Among Women Seeking Asylum in Melbourne, Victoria: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121836

Davidson N, Hammarberg K, Fisher J. Barriers to and Enablers of Preventive Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Among Women Seeking Asylum in Melbourne, Victoria: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121836

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavidson, Natasha, Karin Hammarberg, and Jane Fisher. 2025. "Barriers to and Enablers of Preventive Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Among Women Seeking Asylum in Melbourne, Victoria: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121836

APA StyleDavidson, N., Hammarberg, K., & Fisher, J. (2025). Barriers to and Enablers of Preventive Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Among Women Seeking Asylum in Melbourne, Victoria: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121836