Key Features of Culturally Inclusive, -Affirming and Contextually Relevant Mental Health Care and Healing Practices with Black Canadians: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

- What approaches to mental health care and healing have been used with Black Canadian populations?

- What are recommended practices for mental health care and healing with Black Canadians that are context and culturally informed?

- What gaps exist in the current knowledge of context and culturally informed mental health care and healing approaches with Black Canadians?

2.2. Search

- African, Caribbean, and Black populations (e.g., Africa, Caribbean, Black, names of all African and Caribbean countries, African-centred);

- Canadian context (e.g., Canad*, names of all Canadian provinces, and 100 most populated cities);

- mental health intervention approach (e.g., psychotherapy, counsel*, traditional heal*);

- mental health (e.g., psych*, “mental health”, stress);

- cultural considerations (e.g., culturally sensitive, cultural adaptation, culture safe, culture informed, local adapt*).

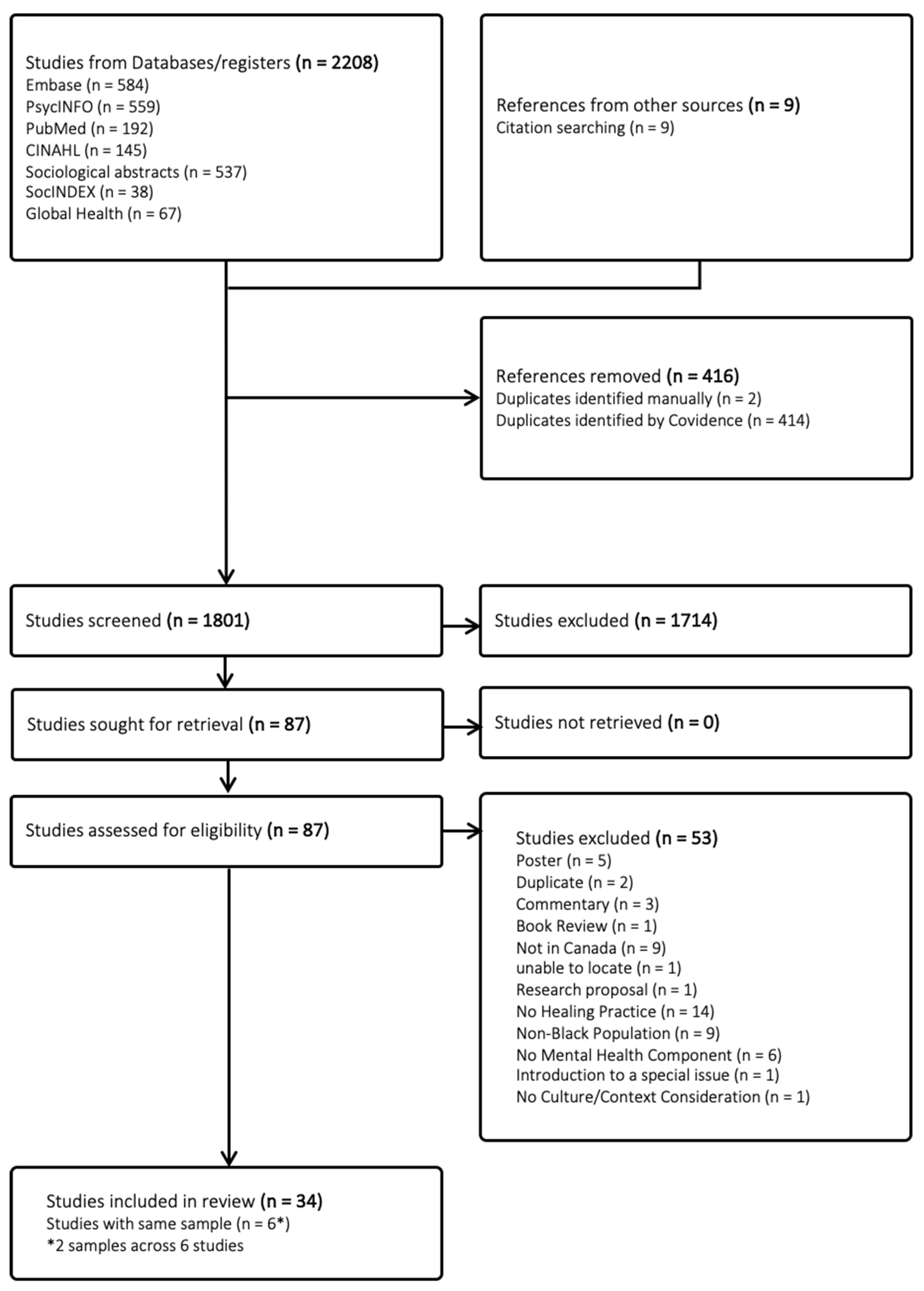

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Article Characteristics

3.2. Methodological Characteristics

3.3. Contextually and Culturally Informed Mental Health Care and Healing Approaches and Practices

3.3.1. Culture Affirming Care (Cultural Safety, Humility and Competency)

3.3.2. Holistic and Empowerment-Based Approach to Mental Health

3.3.3. Social Justice Approach to Mental Health

3.3.4. Community-Centred and Collaborative Healing

3.3.5. Practitioner Education

4. Discussion

4.1. Importance of Culturally Affirming Healing Approaches

4.2. Holistic Approach to Mental Health

4.3. Influence of Systemic and Structural Barriers in Mental Health

4.4. Community and Collective Mental Health Support

4.5. Education and Training of Practitioners in Canada

4.6. Gaps in the Literature Regarding Mental Health Care and Healing Practices

4.7. Limitations and Suggested Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UN | United Nations |

| UNPAD | United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent |

| PHAC | Public Health Agency of Canada |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses- Scoping Review |

| SDoMH | Social Determinants of Mental Health |

| SDoH | Social Determinants of Health |

| 2SLGBTQIA+ | Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, and other identities. |

| CPA | Canadian Psychology Association |

Appendix A. Search Strategy

- (((“African-centered” or “African centered” or “Afrocentric” or “Africentric” or Africa* or “North* Africa*” or “Central Africa*” or “Southern Africa*” or “West* Africa*” or “East* Africa*” or Algeria or Angola or Benin or Botswana or “Burkina Faso” or Burundi or “Cabo Verde” or “Cape Verde” or Cameroon or Central African Republic or Chad or Comoros or Congo or “Cote d’Ivoire” or “Ivory Coast” or Djibouti or Egypt or “Equatorial Guinea” or Eritrea or Eswatini or Ethiopia or Gabon or Gambia or Ghana or Guinea or “Guinea-Bissau” or Kenya or Lesotho or Liberia or Libya or Madagascar or Malawi or Mali or Mauritania or Mauritius or Morocco or Mozambique or Namibia or Niger or Nigeria or Rwanda or “Sao Tome” or Principe or Senegal or Seychelles or “Sierra Leone” or Somalia or “South Africa” or Sudan or Tanzania or Togo or Tunisia or Uganda or Zambia or Zimbabwe) not “african america*”) or (Antigua or Antiguan* or Antilles or Antillean Islands or Aruba or Aruban* or Barbuda or Barbudan* or Bahamas or Bahamian* or Black* or Caribbean or Cuba or Cuban or Curacao or Curacaoan* or Dominica or Dominican* or “Dominican Republic” or Grenada or Grenadian* or Grenadines or Guadeloupe or Guadeloupean* or GuadeloupIan* or Haiti or Haitian or Jamaica* or Martinique or Martiniquais* or Martinican* or Nevis or Nevisian* or “Puerto Rico” or “Puerto Rican*” or “Saint Kitts” or Kittitian* or “Saint Lucia*” or “Saint Vincent” or Vincentian* or “Sint Maarten” or Sint Maartener* or Trinidad* or Trinidadian* or Tobago or Tobagonian* or “Virgin Island*” or “West Indies” or “West Indian*”)).mp. [mp = abstract, title, original title, heading words, cabicodes words] 419,482

- exp Africa/or black people/or African-Caribbeans/or Caribbean Community/

- 1 or 2

- ((Canad* or “British Columbia” or “Colombie Britannique” or Alberta* or Saskatchewan or Manitoba* or Ontario or Quebec or “Nouveau Brunswick” or “New Brunswick” or “Nova Scotia” or “Nouvelle Ecosse” or “Prince Edward Island” or Newfoundland or Labrador or Nunavut or NWT or “Northwest Territories” or Yukon or Nunavik or Inuvialuit) or (Abbotsford or Airdrie or Ajax or Aurora or Barrie or Belleville or Blainville or Brampton or Brantford or Brossard or Burlington or Burnaby or Caledon or Calgary or Cape Breton or Chatham Kent or Chilliwack or Clarington or Coquitlam or Drummondville or Edmonton or Fredericton or Fort McMurray or Gatineau or Granby or Grande Prairie or Sudbury or Guelph or Halton Hills or Iqaluit or Inuvik or Kamloops or Kawartha Lakes or Kelowna or Kingston or Kitchener or Langley or Laval or Lethbridge or Levis or Longueuil or Maple Ridge or Markham or Medicine Hat or Milton or Mirabel or Mississauga or Moncton or Montreal or Nanaimo or New Westminster or Newmarket or Niagara Falls or Norfolk County or North Bay or North Vancouver or Oakville or Oshawa or Ottawa or Peterborough or Pickering or Port Coquitlam or Prince George or Quebec City or Red Deer or Regina or Repentigny or Richmond or Richmond Hill or Saanich or Saguenay or Saint John or Saint-Hyacinthe or Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu or Saint-Jerome or Sarnia or Saskatoon or Sault Ste Marie or Sherbrooke or St Albert or St Catharines or St John’s or Strathcona County or Surrey or Terrebonne or Thunder Bay or Toronto or Trois-Rivieres or Vancouver or Vaughan or ((Cambridge or Halifax or Hamilton or London or Victoria or Waterloo or Welland or Whitby or Windsor) not (UK or Britain or United Kingdom or England or Australia)) or Whitehorse or Winnipeg or Wood Buffalo or Yellowknife)).mp. [mp = abstract, title, original title, heading words, cabicodes words]

- exp Canada/

- 4 or 5

- (Counsel* or Treatment* or Therap* or Psychotherapy* or intervention or “mental health service*” or “psychosocial support*” or “psychosocial intervention*” or “psychosocial program*” or psychiatry* or “global mental health” or “traditional heal*” or “spiritual heal*” or “religious heal*” or “faith heal*” or “traditional medicine” or “traditional African medicine” or “complementary medicine” or “traditional therap*” or “complementary therap*” or “alternative medicine” or “alternative therap*” or “natural medicine” or “herbal medicine” or “folk medicine” or “holistic medicine” or “traditional healing practice*” or “mind–body” or “faith-based mental healthcare” or “faith based mental health care”).mp. [mp = abstract, title, original title, heading words, cabicodes words]

- exp psychotherapy/or exp “complementary and alternative medicine”/or exp traditional medicine/or exp traditional health services/or family counselling/or group counselling/or individual counselling/or leisure counselling/or marriage counselling/

- 7 or 8

- (Psych* or “mental health” or stress or disorder or mental or mind or psychopatholog* or behavioural or behavioral or emotion*).mp. [mp = abstract, title, original title, heading words, cabicodes words] 649,684

- exp mental health/or exp mental disorders/or exp mental stress/or exp emotions/

- 10 or 11

- (cross-cultura* or “cross cultural*” or multicultural or “culture specific” or “culturally specific” or “cultural specific*” or “cultural identi*” or “cultural background*” or “culturally compared” or “culturally compares” or “culturally compare” or “cultural compar*” or “cultural group*” or “cultural aspect*” or “cultural perspective*” or “cultural factor*” or “culturally adapt*” or “cultural adapt*” or “culturally sensitive” or “cultural sensitivit*” or transcultural or “cultural adjustment*” or “culturally adjust*” or “cultural attunement*” or “culturally attune*” or “cultural tailor*” or “culturally tailor*” or “cultural modification*” or “culturally modif*” or “culturally enhance*” or “cultural enhance*” or “culturally ground*” or “cultural equivalen*” or “culturally equivalen*” or “cultural fit” or “cultural awareness” or “culturally aware” or “cultural knowledge” or “culturally knowledg*” or “cultural understanding*” or “culturally understand*” or “cultural expertise” or “cultural skills” or “culturally informed” or “cultural information” or “culturally safe” or “cultural safe*” or “culturally respon*” or “cultural respon*” or “culturally focus*” or “cultural focus*” or “culturally relevant” or “cultural relevance” or “culturally congruent” or “cultural congruence” or “culturally consistent” or “cultural consistency” or “culturally acceptable” or “cultural acceptability” or “contextual adaptat*” or “contextually adapt*” or “local adapt*” or “locally adapt*” or “cultural consideration*” or “culturally consider*” or “culturally suitab*” or “cultural suitab*” or “culturally adequate” or “cultural adequa*” or “culturally appropriate” or “cultural appropriate*” or “cultural influence*” or “culturally influence” or “culturally tailor*” or ethnocentric or “culturally diverse” or “cultural diversi*” or “linguistically diverse” or “linguistic diversi*” or “cultural differen*” or “culturally differen*” or African-centered or “African centered” or Afrocentric or Africentric or indigen* or “Black psychology” or “ethnically diverse” or “ethnic diversity” or “ethnic consideration*” or “culturally compet*” or “culturally-infused” or “culture-infused” or “cultural infusion” or “culturally-resonant” or “contextually relevant” or “tailor*” or “socio-cultural* adapt*” or “psychosocial context” or “social context” or “community-based approach*” or “co-design” or “participatory approach*” or “holistic” or “contextualiz*” or “African setting*” or “community-based”).mp. [mp = abstract, title, original title, heading words, cabicodes words] 124,748

- exp indigenous knowledge/or exp cultural values/1201

- 13 or 14

- 3 AND 6 AND 9 AND 12 AND 15

Appendix B. Article Characteristics

| Article | Study Location | Study Design | Target of Healing Approach | Sample Size | Participant Type | Participant Gender | Participant Age | Approach Target Gender | Approach Target Age |

| Alaazi et al., 2022 [25] | Alberta | Qualitative | General mental health for children and youth. | 81 | Community members | women, men | adult | not specified | children, youth |

| Aryee 2011 [37] | Ontario | Qualitative | Psychospiritual healing women living with HIV/AIDS | 5 | community members, clients | Women | adult | Women | adult |

| Baiden & Evans 2021 [21] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health for postpartum women who immigrated within 5 years. | 10 | Community members | women | adult | women | adult |

| Beagan et al., 2012 [16] | Nova Scotia | Mixed-methods | Mental health impacts of racism | 50 | community members | women | adult, older adult | women | adult |

| Beausoleil et al., 2017 [76] | Ontario | Quantitative | Reintegration for previously incarcerated youth and young adults. | 300 | clients | women, men | youth, adult | men, women | youth, adult |

| Cénat et al., 2023 [77] | Ontario/National | Non-empirical | General mental illness | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | not specified | not specified |

| Dixon & Arthur 2023 [22] | Alberta | Qualitative | Cultural identity | 7 | community members | women | adult | women | adult |

| Fante-Coleman et al., 2023a [36] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health for youth | 128 | community members, service providers, family members of clients, community leaders | women, men, trans, gender-fluid | youth, adult, older adult | not specified | youth |

| Fante-Coleman et al., 2023b [38] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health for youth | 128 | community members, service providers, family members of clients, community leaders | women, men, transgender, gender fluid, third gender | youth, adult, older adult | women, men, 2SLGBTQIA+ | youth |

| Goddard-Durant et al., 2023 [43] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health for young mothers | 13 | Community members | women | youth, adult | women | youth, adult |

| Gopaul-McNicole et al., 1998 [39] | National | Case example | General mental health | 1 | client | women | adult | not specified | not specified |

| Greene 2022 [17] | Ontario | Qualitative | Mental health impacts of racism | 10 | Community members | women, men | adult, older adult | women, men | adult |

| Issack 2015 [40] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health | 8 | community members | women, men | adult | women, men | adult |

| Jarvis et al., 2005 [78] | Quebec | Quantitative | Psychological distress | 1485 | community members | women, men | adult, older adult | women, men | adult |

| Joseph & Kuo 2009 [18] | Ontario | Quantitative | Mental health impacts of racism | 190 | community members | women, men | adult, older adult | women, men | adult, older adult |

| King et al., 2016 [26] | Manitoba | Qualitative | Psychosocial well-being | 15 | community members | women, men | adult | women, men | adult |

| King et al., 2022 [23] | Alberta | Mixed-methods | General mental health for refugees | 174 | service providers, policy makers, community leaders | not specified | adult | not specified | not specified |

| Logie et al., 2016 [46] | Ontario | Qualitative | Social determinants of health for 2SLGBTQIA+ | 29 | clients | women, men, transgender women | adult | women, men, 2SLGBTQIA+ | children, youth, adult, older adult |

| Makwarimba et al., 2013/Stewart et al., 2011/Stewart et al., 2012 [27,28,29] | Ontario and Alberta | Mixed-methods | Social support for refugees | 51–68 | community members, clients service providers | women, men | adult | women, men | adult |

| Moodley & Bertrand 2011 [30] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health | 5 | traditional healers | women, men | adult | women, men | child, youth, adult, older adult |

| Myrie 2021 [24] | National | Qualitative | Childhood sexual abuse recovery for men | 6 | community members | Men | adult | Men | Adult |

| Osazuwa & Moodley 2023 [20] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health | 10 | community members, clients | women, men | adult | not specified | not specified |

| Stewart et al., 2017/Stewart et al., 2018/Stewart et al., 2015 [31,32,33] | Alberta and Ontario | Mixed-methods | Social support for refugee parents | 67–72 | community members, clients, service providers, policy makers | women, men | adult, older adult | women, men | adult |

| Sutherland 2017 [19] | Ontario | Qualitative | Psychological distress/mental health problems | 10 | clients | women, men | adult, older adult | women, men | adult |

| Turner 1991 [44] | Quebec | Case example | Challenges with migration/settlement/integration | 1 | clients | women, men | adult, child | not specified | not specified |

| Ungar 2010 [34] | Ontario | Case example | General mental health; impacts of racism | 1 | client | men | youth | none specified | not specified |

| Waldron & Gayle 2002 [35] | Ontario | Qualitative | General mental health/mental illness | 10 | service providers, community members, clients | women, men | adult, older adult | women | adult |

| Whitley 2016 [41] | Quebec | Qualitative | Mental illness | 47 | clients | women, men | adult, older adult | women, men | adult |

| Yohani & Okeke-Ihejirika 2018 [45] | Alberta | Qualitative | Mental health impacts of sexualized violence | 6 | service providers | women | adult | women | adult |

| Ziral 2009 [42] | Ontario | Qualitative | Spiritual injuries for women | 15 | community members | Women | adult | Women | adult |

References

- Statistics Canada Study: The Sociodemographic Diversity of the Black Populations in Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/241025/dq241025b-eng.htm (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Abdillahi, I.; Shaw, A. Social Determinants and Inequities in Health for Black Canadians: A Snapshot; Public Health Agency of Canada = Agence de santé publique du Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020.

- United Nations Human Rights Council; Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent. Secretariat Report of the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent on Its Mission to Canada; United Nations Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 20.

- McKenzie, K. Racial Discrimination and Mental Health. Psychiatry 2006, 5, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Kogan, C.; Noorishad, P.; Hajizadeh, S.; Dalexis, R.D.; Ndengeyingoma, A.; Guerrier, M. Prevalence and Correlates of Depression among Black Individuals in Canada: The Major Role of Everyday Racial Discrimination. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Dalexis, R.D.; Darius, W.P.; Kogan, C.S.; Guerrier, M. Prevalence of Current PTSD Symptoms among a Sample of Black Individuals Aged 15 to 40 in Canada: The Major Role of Everyday Racial Discrimination, Racial Microaggressions, and Internalized Racism. Can. J. Psychiatry 2023, 68, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, C.S.; Noorishad, P.-G.; Ndengeyingoma, A.; Guerrier, M.; Cénat, J.M. Prevalence and Correlates of Anxiety Symptoms among Black People in Canada: A Significant Role for Everyday Racial Discrimination and Racial Microaggressions. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 308, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Promoting Health Equity: Mental Health of Black Canadians Fund (2018–2024); Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024; pp. 3–11.

- Firth, K.; Smith, K.; Sakallaris, B.R.; Bellanti, D.M.; Crawford, C.; Avant, K.C. Healing, a Concept Analysis. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2015, 4, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, J. What Is “Healing”?: Reflections on Diagnostic Criteria, Nosology, and Etiology. Explore 2017, 13, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wampold, B.E. Contextualizing Psychotherapy as a Healing Practice: Culture, History, and Methods. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 2001, 10, 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Rethinking the Concept and Measurement of Societal Culture in Light of Empirical Findings. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beagan, B.L.; Etowa, J.; Bernard, W.T. “With God in Our Lives He Gives Us the Strength to Carry on”: African Nova Scotian Women, Spirituality, and Racism-Related Stress. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2012, 15, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K. “A Rough Road to the Stars”: Exploring Resilience through Overcoming the Trauma of Anti-Black Racism. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, J.; Kuo, B.C.H. Black Canadians’ Coping Responses to Racial Discrimination. J. Black Psychol. 2009, 35, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, P.T. Cultural Constructions of Trauma and the Therapeutic Interventions of Caribbean Healing Traditions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Osazuwa, S.; Moodley, R. “Will There Be a Willingness to Actually Engage with It?”: Exploring Attitudes toward Culturally Integrative Psychotherapy among Canada’s African Community. J. Psychother. Integr. 2023, 33, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiden, D.; Evans, M. Black African Newcomer Women’s Perception of Postpartum Mental Health Services in Canada. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 53, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.; Amin, D.; Arthur, N. Giving Voices to Jamaican Canadian Immigrant Women: A Heuristic Inquiry Study. Qual. Rep. 2023, 28, 2172–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.U.; Este, D.C.; Yohani, S.; Duhaney, P.; McFarlane, C.; Liu, J.K.K. Actions Needed to Promote Health Equity and the Mental Health of Canada’s Black Refugees. Ethn. Health 2022, 27, 1518–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myrie, Z. The Experience of Recovery from Childhood Sexual Abuse among Black Men. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alaazi, D.A.; Salami, B.; Ojakovo, O.G.; Nsaliwa, C.; Okeke-Ihejirika, P.; Salma, J.; Islam, B. Mobilizing Communities and Families for Child Mental Health Promotion in Canada: Views of African Immigrants. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 139, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.U.; Heinonen, T.; Uwabor, M.; Adeleye-Olusae, A. The Psychosocial Well-Being of African Refugees in Winnipeg: Critical Stressors and Coping Strategies. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2017, 15, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwarimba, E.; Stewart, M.; Simich, L.; Makumbe, K.; Shizha, E.; Anderson, S. Sudanese and Somali Refugees in Canada: Social Support Needs and Preferences. Int. Migr. 2013, 51, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Simich, L.; Beiser, M.; Makumbe, K.; Makwarimba, E.; Shizha, E. Impacts of a Social Support Intervention for Somali and Sudanese Refugees in Canada. Ethn. Inequalities Health Soc. Care 2011, 4, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Simich, L.; Shizha, E.; Makumbe, K.; Makwarimba, E. Supporting African Refugees in Canada: Insights from a Support Intervention. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, R.; Bertrand, M. Spirits of a Drum Beat: African Caribbean Traditional Healers and Their Healing Practices in Toronto. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2011, 49, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Makwarimba, E.; Letourneau, N.L.; Kushner, K.E.; Spitzer, D.L.; Dennis, C.-L.; Shizha, E. Impacts of a Support Intervention for Zimbabwean and Sudanese Refugee Parents: “I Am Not Alone”. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 47, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; Kushner, K.E.; Dennis, C.L.; Kariwo, M.; Letourneau, M.; Makumbe, K.; Makwarimba, E.; Shizha, E. Social Support Needs of Sudanese and Zimbabwean Refugee New Parents in Canada. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2017, 13, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Spitzer, D.L.; Kushner, K.E.; Shizha, E.; Letourneau, N.; Makwarimba, E.; Dennis, C.-L.; Kariwo, M.; Makumbe, K.; Edey, J. Supporting Refugee Parents of Young Children: “Knowing You’re Not Alone”. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2018, 14, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. Families as Navigators and Negotiators: Facilitating Culturally and Contextually Specific Expressions of Resilience. Fam. Process 2010, 49, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, I. African Canadian Women Storming the Barricades!: Challenging Psychiatric Imperialism through Indigenous Conceptualizations of “Mental Illness” and “Self-Healing”. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fante-Coleman, T.; Jackson-Best, F.; Booker, M.; Worku, F. Organizational and Practitioner Challenges to Black Youth Accessing Mental Health Care in Canada: Problems and Solutions. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2023, 64, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, E. The Psycho-Spirituality of African Women Living with HIV/AIDS in Ontario. Can. Woman Stud./Les Cah. Femme 2011, 29, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Fante-Coleman, T.; Allen, K.; Booker, M.; Craigg, A.; Jackson-Best, F. “If You Prayed More, You Would Feel Better”: The Dual Nature of Religion and Spirituality on Black Youths’ Mental Health and Access to Care in Canada. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2024, 41, 919–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopaul-Mcnichol, S.-A.; Benjamin-Dartigue, D.; Francois, E. Working with Haitian Canadian Families. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 1998, 20, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issack, S. Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviour: African Immigrants’ Experience. Master’s Thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, R. Ethno-Racial Variation in Recovery from Severe Mental Illness: A Qualitative Comparison. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziral, H.P. Resilient Iris Intergenerational Spirit Injury of Diasporic African Women Spirit Healing and Recovery. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard-Durant, S.K.; Doucet, A.; Tizaa, H.; Sieunarine, J.A. “I Don’t Have the Energy”: Racial Stress, Young Black Motherhood, and Canadian Social Policies. Can. Rev. Sociol. 2023, 60, 542–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.E. Migrants and Their Therapists: A Trans-context Approach. Fam. Process 1991, 30, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohani, S.; Okeke-Ihejirika, P. Pathways to Help-Seeking and Mental Health Service Provision for African Female Survivors of Conflict-Related Sexualized Gender-Based Violence. Women Ther. 2018, 41, 380–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Lee-Foon, N.; Ryan, S.; Ramsay, H. “It’s for Us –Newcomers, LGBTQ Persons, and HIV-Positive Persons. You Feel Free to Be”: A Qualitative Study Exploring Social Support Group Participation among African and Caribbean Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Newcomers and Refugees in Toronto, Canada. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2016, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Jarvis, G.E. Culturally Responsive Services as a Path to Equity in Mental Healthcare. Healthc. Pap. 2019, 18, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateef, H.; Amoako, E.O.; Nartey, P.; Tan, J.; Joe, S. Black Youth and African-Centered Interventions: A Systematic Review. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2021, 32, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateef, H.; Nartey, P.B.; Amoako, E.O.; Lateef, J.S. A Systematic Review of African-Centered Therapeutic Interventions with Black American Adults. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2022, 50, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Faber, S.C.; Duniya, C. Being an Anti-Racist Clinician. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2022, 15, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, R.; Sutherland, P. Psychic Retreats in Other Places: Clients Who Seek Healing with Traditional Healers and Psychotherapists. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2010, 23, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, L.; Barber, S.; Ahuja, S.; Thornicroft, G.; Henderson, C.; Lempp, H.; N’Danga-Koroma, J. Evidence for Interventions to Promote Mental Health and Reduce Stigma in Black Faith Communities: Systematic Review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahdaninia, M.; Simkhada, B.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Blunt, H.; Mercel-Sanca, A. Mental Health Services Designed for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnics (BAME) in the UK: A Scoping Review of Case Studies. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2020, 24, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.; Zijlstra, G.; McGrath, M.; Lee, C.; Duncan, F.H.; Oliver, E.J.; Osborn, D.; Dykxhoorn, J.; Kaner, E.F.S.; LaFortune, L.; et al. Community-Centred Interventions for Improving Public Mental Health among Adults from Ethnic Minority Populations in the UK: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratts, M.J.; Singh, A.A.; Nassar-McMillan, S.; Butler, S.K.; McCullough, J.R. Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies. 2015. Available online: https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=20 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Hays, K.; Aranda, M.P. Faith-Based Mental Health Interventions with African Americans: A Review. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2016, 26, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankerson, S.H.; Weissman, M.M. Church-Based Health Programs for Mental Disorders among African Americans: A Review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, D.W.; Roche, M.; Billings, J. Evaluating Interventions That Have Improved Access to Community Mental Health Care for Black Men: A Systematic Review. J. Ment. Health 2025, 34, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, J.; Hays, K.; Gamez, A.M. Using Mental Health First Aid to Promote Mental Health in Churches. J. Spirit. Ment. Health 2021, 23, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.A.; Kassan, A.; Wada, K.; Arthur, N.; Goopy, S. Enhancing Multicultural and Social Justice Competencies in Canadian Counselling Psychology Training. Can. Psychol. 2022, 63, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, G.E.; Andermann, L.; Ayonrinde, O.A. Taking Action on Racism and Structural Violence in Psychiatric Training and Clinical Practice. Can. J. Psychiatry 2023, 68, 780–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Psychological Association. Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists, 4th ed.; Canadian Psychological Association: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017; ISBN 978-1-926793-11-5. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Psychological Association. Accreditation Standards for Doctoral and Residency Programs in Professional Psychology, 6th ed.; Canadian Psychological Association: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023; ISBN 978-1-926793-13-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sarr, F.; Knight, S.; Strauss, D.; Ouimet, A.J.; Cénat, J.M.; Williams, M.T.; Shaughnessy, K. Increasing the Representation of Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour as Students in Psychology Doctoral Programmes. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2022, 63, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.D.; Williams, J.M.; Chung, R.C.-Y.; Talleyrand, R.M.; Douglass, A.M.; McMahon, H.G.; Bemak, F. Decolonizing Traditional Pedagogies and Practices in Counseling and Psychology Education: A Move towards Social Justice and Action. In Decolonizing “Multicultural” Counseling Through Social Justice; Goodman, R.D., Gorski, P.C., Eds.; International and Cultural Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 147–164. ISBN 978-1-4939-1282-7. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.-T.; Doyle, E.M. Preparing Student Therapists to Work with Black Mental Health: Attending to the Social and Institutional Organization of “Culture” in Canadian Counsellor Education. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2022, 63, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Broussard, C.; Jacob, G.; Kogan, C.; Corace, K.; Ukwu, G.; Onesi, O.; Furyk, S.E.; Bekarkhanechi, F.M.; Williams, M.; et al. Antiracist Training Programs for Mental Health Professionals: A Scoping Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 108, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke-Ihejirika, P.; Yohani, S.; Salami, B.; Rzeszutek, N. Canada’s Sub-Saharan African Migrants: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 79, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, N.; Jackson, S.F.; Wong, K.; Yessis, J.; Jetha, N. Between Worst and Best: Developing Criteria to Identify Promising Practices in Health Promotion and Disease Prevention for the Canadian Best Practices Portal. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pract. 2017, 37, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K.; Khenti, A.; Vidal, C.; Williams, C.C.; Joseph, J.; Ahmed, K.; Mohamoud, S.; Aryee, E.; Browne, N. Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for English-Speaking People of Caribbean Origin: A Manual for Enhancing the Effectiveness of CBT for English-Speaking People of Caribbean Origin in Canada, 1st ed.; Ballon, D., Gamble, N., Waller-Vintar, J., Eds.; Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011; ISBN 978-1-77052-872-7. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.T.; Davis, A.K.; Xin, Y.; Sepeda, N.D.; Grigas, P.C.; Sinnott, S.; Haeny, A.M. People of Color in North America Report Improvements in Racial Trauma and Mental Health Symptoms Following Psychedelic Experiences. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2021, 28, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Reed, S.; George, J. Culture and Psychedelic Psychotherapy: Ethnic and Racial Themes from Three Black Women Therapists. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2021, 4, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.T.; Faber, S.C.; Buchanan, N.T.; Foster, D.; Green, L. The Need for Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy in the Black Community and the Burdens of Its Provision. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 774736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black Wellness Network MHCB Project Resources. Available online: https://blackwellnessnetwork.ca/mhbc-project-resources/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Black Wellness Network. Towards Positive Change to Promote Mental Health and Wellbeing: A Toolkit for Black Canadians; Barbados Association of Winnipeg (in collaboration with partner organizations): Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2021; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Beausoleil, V.; Renner, C.; Dunn, J.; Hinnewaah, P.; Morris, K.; Hamilton, A.; Braithewaite, S.; Hunter, N.; Browne, G.; Browne, D.T. The Effect and Expense of Redemption Reintegration Services versus Usual Reintegration Care for Young African Canadians Discharged from Incarceration. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Lashley, M.; Jarvis, G.E.; Williams, M.T.; Bernheim, E.; Derivois, D.; Rousseau, C. The Burden of Psychosis in Black Communities in Canada: More than a Feeling, a Black Family Experience. Can. J. Psychiatry 2024, 69, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, G.E.; Kirmayer, L.J.; Weinfeld, M.; Lasry, J.-C. Religious Practice and Psychological Distress: The Importance of Gender, Ethnicity and Immigrant Status. Transcult. Psychiatry 2005, 42, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Themes/Approach | Sub-Themes/Recommended Practices |

|---|---|

| Culture Affirming Care (Cultural Safety, Humility and Competency) | Culture-Specific and Traditional Healing Practices Recognition and Incorporation of Spirituality and/or Religion Option for Black Mental Health Service Providers Address Mental Health Stigma Recognition and Incorporation of Family and Community |

| Holistic and Empowerment-Based Approach to Mental Health | Use Holistic and Flexible Approaches Use Collaborative and Client-centred Approaches Use Strengths-Based and Resilience-Enhancing Approaches Use Trauma-Focused and Informed Approaches Use Family-Focused Approaches |

| Social Justice Approach to Mental Health | Address Racism and Racism-Related Stress Attend to Social Determinants of Health Take an Intersectional Lens Engage in Advocacy |

| Community-Centred and Collaborative Healing | Mobilize Informal Community Social Support Use Collective Approaches Engage in Multidisciplinary and Community Collaboration |

| Practitioner Education | Practitioner Knowledge and Skills Critical Reflexivity and Consciousness Raising |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yohani, S.; Devereux, C. Key Features of Culturally Inclusive, -Affirming and Contextually Relevant Mental Health Care and Healing Practices with Black Canadians: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091316

Yohani S, Devereux C. Key Features of Culturally Inclusive, -Affirming and Contextually Relevant Mental Health Care and Healing Practices with Black Canadians: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091316

Chicago/Turabian StyleYohani, Sophie, and Chloe Devereux. 2025. "Key Features of Culturally Inclusive, -Affirming and Contextually Relevant Mental Health Care and Healing Practices with Black Canadians: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091316

APA StyleYohani, S., & Devereux, C. (2025). Key Features of Culturally Inclusive, -Affirming and Contextually Relevant Mental Health Care and Healing Practices with Black Canadians: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091316