Abstract

Background: Population ageing is a global challenge, prompting ageing-in-place policies in Hong Kong to support community-dwelling older adults while reducing healthcare costs. Yet, their impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) remains underexplored amid Hong Kong’s long life expectancy and growing older population. Traditional surveys are costly and time-consuming, while routinely collected registration data offers a large, efficient source for health insights. This study uses enhanced administrative data to track HRQoL trajectories and inform policy. Methods: This is a prospective, open-ended longitudinal study, enrolling adults aged 50 or older from a collaborating non-governmental organization in Hong Kong’s Southern District. Data collection, started in February 2021, occurs annually via phone and face-to-face interviews by trained social workers and volunteers using a standardized questionnaire to assess individual (e.g., socio-demographics), environmental (e.g., social support via Lubben Social Network Scale-6), biological (e.g., chronic illnesses), functional (e.g., cognition via Montreal Cognitive Assessment), and HRQoL (e.g., EQ-5D-5L) factors. A secure online system links health and service use data (e.g., service utilization like community care visits). Analysis employs descriptive statistics, group comparisons, correlations, growth modelling to identify health trajectories, and structural equation modelling to test a revised quality-of-life framework. Sample size (projected 470–580 after two follow-ups from a 2321 baseline) is based on power calculations: 300–500 for latent class growth analysis (LCGA) class detection and 200–400 for structural equation modelling (SEM) fit (e.g., RMSEA < 0.06) at 80% power/α = 0.05, simulated via Monte Carlo with a 50–55% attrition. Discussion: This is the first longitudinal HRQoL study in Hong Kong using enhanced non-governmental organization (NGO) administrative data, integrating social–ecological and HRQoL models to predict trajectories (e.g., stable vs. declining mobility) and project care demands (e.g., increase in in-home care for frailty). Unlike prior cross-sectional or inpatient studies, it offers a scalable model for NGOs, informing ageing-in-place policy effectiveness and equitable geriatric care.

1. Introduction

Population ageing is a global challenge, prompting the widespread adoption of ageing-in-place policies to support older adults in remaining at home [1]. These policies are assumed to preserve social connections while offering a cost-effective alternative to overburdened healthcare systems [2,3,4]. However, their impact on quality of life remains underexplored, with evidence suggesting that ageing-in-place does not inherently ensure independence or well-being, as health, mobility, and social challenges may compromise outcomes [5,6,7]. Ageing-in-place is the ability of older adults to live safely and independently in their own homes and communities, supported by services that maintain their health and quality of life rather than moving to institutional care [2]. Given the heterogeneity of ageing experiences, understanding individual health trajectories is critical to optimizing these policies’ benefits.

Quality of life, as defined by the World Health Organization, encompasses individuals’ perceptions of their position in life within the context of their culture and value systems [8]. To provide a more practical focus, Patrick and Erickson introduced the term “health-related quality of life” (HRQoL), which considers the impact of health, illness, and treatment on quality of life [9,10]. However, a clear research gap remains: current HRQoL studies among community-dwelling older adults are insufficient for evaluating ageing-in-place and guiding care because they typically concentrate on specific subpopulations and narrow outcomes [11,12,13], emphasize single risk factors rather than the interactions among multimorbidity, functional decline, and social context [14,15,16], and rely on resource-intensive, survey-based designs that are episodic and small-scale, limiting representativeness and the ability to track longitudinal trajectories and timely change [17,18,19,20,21].

Community care providers are crucial for monitoring health risks and delivering interventions to sustain HRQoL, but the variability and complexity of older adults’ needs demand comprehensive, longitudinal, multi-domain data that extend beyond single risk factors [14,15,16]. Traditional surveys rarely meet these requirements due to cost and operational burden [17,18,19,20,21]. In contrast, purposefully built member registration administrative data—collected longitudinally for service delivery with large volume—can directly overcome these limitations: they provide time-stamped, repeated observations across diverse older adults; capture service use and care processes (e.g., visit types, intensity, and referrals) that are actionable for providers; support the integration of clinical and social care records to enable multi-factor risk modelling; and are updated routinely, allowing near-real-time monitoring, trajectory analysis, and the evaluation of ageing-in-place interventions at scale [17,18,19,20,21].

In Hong Kong, where life expectancy reaches 82 for males and 88 for females [22], the 65+ population is projected to grow from 18.4% (1.32 million) in 2019 to 33.3% (2.52 million) by 2039 [22], intensifying HRQoL demands [23]. Common health needs include chronic illnesses (e.g., hypertension: 58.4%, diabetes: 14% [24]), mobility issues [24], depression (8.4% [24]), suicidal ideation (1.2%) [25], and social isolation (13% living alone [24,26]; 30.4% not participating in social activities [27]), driving the demand for community care. Since 1977, Hong Kong has prioritized ageing-in-place supported by NGO-led community care and, since 2019, District Health Centres (DHCs) to promote self-managed health. DHCs provide district-based services like chronic disease screening, health education, and rehabilitation to enable independent living and reduce institutionalization [28,29]. Although ageing-in-place is popular among older Chinese city-dwellers in Hong Kong, its long-term impact on HRQoL remains under-researched [30,31,32]. Community care providers, including District Health Centres and NGOs, routinely collect data on chronic conditions, health events (e.g., falls, hospitalizations), functional status, and service use during screenings [28,29]. These factors can serve as covariates to predict HRQoL trajectories.

This study will establish a structured longitudinal database with purposefully built member registration administrative data to address the insufficient knowledge regarding community healthcare needs in Hong Kong. Since the key limitation of administrative data is that it is not originally collected for research purposes [17], the research team co-designed a comprehensive assessment system with a collaborating NGO to support robust data collection and statistical analyses. The assessment system is also linked to the service utilization record of each registered member to examine service allocation efficiency. The study results will be shared with community members, who are viewed as having the best knowledge about improving the health of their community [33]. This community health promotion approach is expected to increase community members’ control over their health, address health inequalities, and enhance the well-being of the community [34].

2. Methods

2.1. Aims

This study has three specific objectives: (1) to establish a purposefully built member registration administrative database longitudinally tracking HRQoL trajectories among community-dwelling older adults; (2) to refine and validate a revised HRQoL model based on Ferrans et al. [10], integrating multi-level risk factors leveraged on the database; and (3) to assess the effectiveness of ageing-in-place policies on HRQoL by analyzing health trajectories and service needs. At the individual level, the database will identify risk factors and at-risk groups to enable early intervention. At the organizational level, linking service utilization records will optimize resource allocation and management. At the community level, the database will aggregate trajectories to anticipate social care (e.g., social support programmes) and long-term care demands (both in-home services like nursing/physiotherapy and institutional backup for severe decline), informed by HRQoL, medical needs (e.g., chronic conditions, health events via eHealth-linked records), functional status, and service utilization trends.

2.2. Conceptual Framework for Health-Related Quality of Life

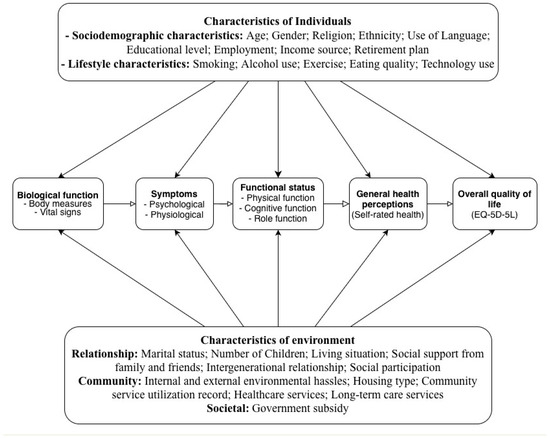

This study integrates McLeroy et al.’s social–ecological approach with Ferrans et al.’s revised HRQoL model to create a multi-level framework [10,35]. The social–ecological approach posits that ageing-in-place policies impact health variably due to individual and environmental interactions, making it ideal for examining longitudinal policy effects [35]. Ferrans et al. refine Wilson and Cleary’s model linking biological function, symptoms, functional status, general health perceptions, and HRQoL, with individual (e.g., demographic, psychological) and environmental (e.g., social, physical) influences explicitly defined [10]. McLeroy et al.’s model complements Ferrans et al.’s by expanding environmental characteristics into interpersonal and community levels, enabling rigorous analysis of multi-level influences on the HRQoL. Validated across conditions like HIV/AIDS [36], heart failure [37], and cancer [38], and predictive of mortality and service use in older adults [39], this model is robust [40,41]. We extend it by incorporating Zubritsky et al.’s ageing-specific additions (cognition, behaviour, and long-term services) and applying it to Hong Kong’s community-dwelling older population [42] (Figure 1). The revised HRQoL model is culturally adapted for Hong Kong’s older adults by incorporating variables like intergenerational relationships and caregiving stress, reflecting Confucian values, and using validated tools (e.g., EQ-5D-5L, CZBI-Short) tailored to Chinese older adults [43,44,45]. This ensures relevance in the context of family-centric care and urban ageing-in-place policies [30,31]. In Hong Kong’s Confucian-influenced culture and ageing-in-place policy (e.g., NGO care and DHCs), this integration captures how family/community supports moderate health pathways, addressing gaps in prior studies.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of health-related quality of life for community-dwelling older adults.

2.3. Study Design

This is a community-based, multicenter, prospective, open-ended longitudinal study with ongoing data collection via phone and face-to-face interviews in Hong Kong’s Southern District. At the time of registration for the membership (during the baseline visit), participants are encouraged to attend as many annual follow-up visits as possible.

2.4. Study Setting

The Southern District, one of Hong Kong’s 18 districts, has 263,278 residents (3.6% of the territory’s population), with 21.6% aged 65+—among the top five ageing districts [26,46]. Its post-intervention poverty rate is 6.1%, reflecting a socioeconomically diverse population with public (45.7% of Hong Kong residents in 2021) and private (53.7%) housing [47,48,49]. The Southern District’s high proportion of older population and housing diversity make it suitable, but its lower poverty rate (6.1% vs. Hong Kong’s 7.9%) and urban access to DHCs may have a potential to limit representativeness for some other districts [26,46,47]. Findings, however, remain transferable due to shared ageing-in-place policies and methodological adjustments [28,29].

2.5. Study Sample

This study will include as many eligible subjects as are willing to participate. Participants are members of a collaborating NGO, registering after February 2021, aged ≥50, and of any gender or ethnicity. Exclusion criteria include inability to provide informed consent (e.g., severe cognitive impairment). Members pay an annual fee of HKD 20–30 for services, waived for Comprehensive Social Security Assistance recipients. Follow-ups occur at annual membership renewals. The study sample differs demographically from the general Southern District population due to non-random, convenience sampling based on NGO membership, resulting in a sample skewed toward more socially engaged, older, female, and lower-income individuals. This will be addressed analytically. The sample size for this longitudinal cohort study was calculated to ensure sufficient statistical power to achieve its objectives: tracking HRQoL trajectories, validating a revised HRQoL model, and evaluating ageing-in-place policies among community-dwelling older adults in Hong Kong’s Southern District. Targeting a minimum baseline sample of 1600–2500 participants, the calculation accounts for key analyses, including latent class growth analysis (LCGA) and structural equation modelling (SEM), which require 300–500 and 200–400 participants, respectively, to detect small to moderate effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d = 0.3 for HRQoL changes) with 80% power and alpha = 0.05 [50,51]. The sample size (n = 2321 baseline, targeting 470–580 post-two follow-ups) assumes a small-to-moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.3 for LCGA; standardized β = 0.2–0.3 for SEM) to detect HRQoL trajectory differences (e.g., EQ-5D-5L changes) and model relationships (e.g., social support to function) at 80% power, α = 0.05 [50,51]. Subgroup analyses by gender, age (50–64 vs. ≥65), chronic conditions, and housing type will target 100–150 participants per group to detect moderate effects, and weighted models will address sampling imbalances (e.g., female over-representation) [24,27]. Pilot-phase attrition at the first follow-up was 71% (670 of 2321 retained), driven by selective follow-up due to specific target requirements and manpower limits rather than true loss to follow-up. A reduced attrition rate of 50–55% (retention rate of 45–50%) was assumed for subsequent follow-ups, leveraging the NGO’s outreach services (e.g., regular contact and support programmes) to improve retention [52]. Although early attrition exceeded projections, improved retention in later cohorts supports a target of 470–580 retained participants, consistent with Hong Kong studies reporting a 20–30% annual loss in older cohorts [24]. To maintain 400 participants for LCGA/SEM after two follow-ups with 50–55% attrition per follow-up, the baseline sample was inflated (e.g., 400/(1 − 0.525)2 ≈ 1807, where 0.525 is the midpoint) [52]. The current enrollment of 2321 participants exceeds this requirement, yielding approximately 470–580 participants after two follow-ups, supporting robust subgroup analyses and accommodating heterogeneity in health needs. This sample size is justified by the need to capture diverse HRQoL trajectories, address gender imbalances through targeted male recruitment, and provide generalizable insights for policy in a rapidly ageing population, with ongoing open-ended recruitment further ensuring adequacy if attrition exceeds expectations [52].

2.6. Data Collection

Pilot data collection began in February 2021. By the end of 2024, 2321 participants completed baseline questionnaires, and 670 and 155 participants completed first and second follow-ups, respectively, with selective follow-ups due to specific target requirements and manpower constraints, not full attrition. Participants were prioritized based on engagement or data completeness, testing feasibility. Registered social workers conducted baseline interviews, with trained volunteers assisting in follow-ups. Follow-ups are hybrid (in-person preferred; phone if absent [53]), with loss after three contact attempts [27]. Renewal is voluntary and decoupled from surveys. To mitigate attrition, a concrete retention plan includes flexible data collection modes, personalized reminders, community-building activities, and family and proxy involvement [54,55]. Baseline written consent suffices annually, with no financial incentives but service priorities. Data are collected annually to track HRQoL trajectories. We will have at least three data points (baseline + 2 follow-ups) to estimate trajectories. Baseline interviews, conducted by trained social workers, take 30–45 min, while follow-ups (about 30 min) use skip-logic to reduce burden. Breaks and hybrid formats (in-person/phone) accommodate older participants.

2.7. Assessment and Measurement

Our collaborating NGO collects users’ records (e.g., demographics, subsidies), service utilization/health events (e.g., Home Support Service users: frequency of nursing visits, falls, and hospitalizations) in routine, which have been integrated with assessments to track HRQoL longitudinally. These administrative data can enhance HRQoL assessment, providing real-world context and enabling robust longitudinal analyses of health trajectories. A standardized questionnaire, informed by the conceptual framework, assessing variables across five domains (Table 1), was purposefully designed. The instruments used are culturally validated for Hong Kong Chinese participants, with data collection by Cantonese-speaking staff to ensure cultural sensitivity [25,56].

Table 1.

Summery table of the variables of interest on the conceptual model.

Individual Characteristics. Sociodemographic (e.g., age, gender, and education) and lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, exercise) capture personal influences on HRQoL.

Environmental Characteristics. Environmental characteristics are assessed across three domains reflecting external influences on HRQoL, per the social–ecological framework: (1) relationship factors, including marital status, number of children, living situation, social support via LSNS-6 [25], intergenerational relationship [43], and social participation; (2) community factors, such as internal and external environmental hassles (e.g., home hazards, accessibility), housing type (e.g., public or private), and service utilization that is contingent on individual needs (e.g., recent hospital discharge requiring intensive nursing vs. routine medication management), quantified by frequency (visits/month), type (medical/social), and intensity (duration), linked to assessments like GDS-15 scores or fall history for tailored allocation; and (3) societal factors, specifically government subsidies (e.g., Comprehensive Social Security Assistance, Old Age Allowance, Old Age Living Allowance, Disability Allowance, and Mandatory Provident Fund). The LSNS-6, validated in older Chinese populations, measures the social network size and quality [25]. The attitudes toward young people questionnaire, adapted from Pinquart and Silvia [43], uses a 13-item semantic differential scale (7-point, scores 13–91, and higher = more positive), translated into Chinese via forward-and-backward methods, with good reliability in our prior study (Cronbach’s α = 0.787–0.823).

Biological Function. Height, weight with Body Mass Index (BMI), and blood pressure are measured at registration to monitor physical health.

Symptoms. The symptoms include the following: (1) psychological (depressive and anxiety symptoms, loneliness, and stressful events) and (2) physiological (self-reported chronic illnesses, sleep quality, falls, pain, and gait). Depressive symptoms are screened with the PHQ-2, followed by severity assessment using the GDS-15, both validated in Hong Kong [57].

Functional Status. Functional status includes the following: (1) physical function including ADL via Modified Barthel Index; IADL via Lawton’s scale, validated in Chinese [58]; walking ability; and assisted device use; (2) cognitive function using MoCA, validated in Hong Kong, with trained staff [56]; and (3) role function including volunteering via VFI and VSI [59] and caregiving via BAFFS, CZBI-Short, and PHQ-2 [44,57,60]. VFI assesses volunteer motives; VSI measures outcomes; and BAFFS, CZBI-Short, and PHQ-2 evaluate the caregiving burden and family function.

General Health Perception. General health perceptions (GHP) are assessed with a single self-rated item, “In general, how is your health?” scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very good, 5 = very poor) with a lower score indicating more positive health perception [61].

HRQoL (outcome variable). HRQoL is evaluated using the self-reported EQ-5D-5L, validated for Hong Kong Chinese [45]. It assesses five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) on a 1–3 Likert scale (1 = no difficulty, 3 = extreme difficulty), converted to an index (negative = poor HRQoL, ~1 = no issues) [45]. It includes an EQ-VAS (0–100; 0 = worst, 100 = best health). Reliability is good with Cronbach’s α = 0.77.

2.8. Data Management and Storage

Participants are assigned unique IDs to anonymize and link questionnaire responses and service records. Data are entered into a custom online system with checks to prevent missing items and logic errors during interviews. They are stored on an encrypted, password-protected university platform (AES-256 standard) [62] and backed up daily on both the survey system and platform servers. Data management complies with Hong Kong’s Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Cap. 486) [63].

2.9. Data Analysis

Data analysis begins with descriptive statistics to summarize demographic variables and sample characteristics. Normality of observed variables is assessed using mean, median, skewness, and kurtosis to ensure distributional assumptions for subsequent tests. Group differences are examined with independent-sample t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA), assuming normality and equal variances where applicable. Relationships among key variables (e.g., HRQoL, functional status, and symptoms) are explored using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. For longitudinal analysis, latent class growth analysis (LCGA) identifies subgroups with distinct HRQoL trajectories, capturing variations in initial levels and growth patterns over time, aligning with the study’s aim to track health trajectories. Multinomial logistic regression then determines factors influencing these trajectories, reporting relative risk ratios (RRRs) with 95% confidence intervals. Structural equation modelling (SEM) tests the revised HRQoL model, evaluating direct and indirect effects with fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA) [64]. Contingencies are modelled as time-varying covariates in LCGA/SEM (e.g., post-discharge events predicting higher utilization in declining HRQoL trajectories). Missing data will be handled using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) for LCGA/SEM, assuming missing at random (MAR), with Little’s test for missing completely at random (MCAR), and multiple imputation as a backup for non-MAR cases (e.g., health-related attrition) to ensure robust estimates [65]. We will assess normality (absolute skew ≤ 2, kurtosis ≤ 7) and, if violated, use MLR with bootstrapping (≥2000 resamples); LCGA selection will prioritize lower BIC/AIC, entropy ≥ 0.80, and significant VLMR/BLRT (p < 0.05) with parsimony and class sizes ≥ 5%; SEM fit will target CFI/TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and SRMR ≤ 0.08, with robust chi-square reported only; and WLSMV will be used for ordinals [50,65]. Analyses are conducted using RStudio, R version 4.3.2 (data processing), SPSS version 29 (descriptive and basic statistics), and Mplus 8 (LCGA and SEM).

3. Discussion

This study significantly advances the growing body of literature on the revised Wilson–Cleary HRQoL model by applying it to community-dwelling older adults in Hong Kong with heterogeneous healthcare needs, thereby broadening the understanding of the ageing process from a longitudinal perspective. To our knowledge, it represents the first longitudinal study among this population to utilize administrative data, offering an innovative and cost-effective solution for routinely collecting personal health data and systematically linking them with service utilization records. The longitudinal dataset generated through this approach enables researchers to predict diverse health trajectories and investigate the risk factors associated with each trajectory, addressing a critical gap in ageing-in-place research. Unlike large survey cohorts (SHARE/ELSA/CHARLS), this study uses NGO administrative data to reduce recall bias and create linkages to real-world events; though the sample is smaller, the approach is scalable across NGOs.

Building on the ageing-in-place framework outlined in the Introduction (e.g., NGO-led home-based care and District Health Centres’ preventive screenings [28,29]), the custom big data system developed for this study serves as a scalable model for other NGOs operating senior service units. In Hong Kong’s context, where policies emphasize subsidized in-home support (e.g., nursing, meal delivery) and community programmes to manage chronic conditions while reserving institutional care for severe cases, by modelling trajectories with multifaceted data (beyond HRQoL, including medical needs like chronic illnesses and prior events), the database projects community-level demands—e.g., increased in-home care for low HRQoL to sustain ageing-in-place—or institutional needs if trajectories indicate irreversible decline. This system supports further investigation into the impact, appropriateness, and effectiveness of ageing-in-place policies in Hong Kong, providing a comprehensive and data-driven framework. The study’s results will be used to advise Hong Kong’s Social Welfare Department and Health Bureau—forecasting care needs to guide District Health Centre expansion and subsidy allocation [28,29]—while co-developing interventions with NGOs through community forums and publishing to promote scalable ageing-in-place models [65]. Through these efforts, the study aims to enhance the quality of life for older adults and inform both policy development and practical improvements in geriatric care. Cultural adaptation of the HRQoL model, through validated tools and community engagement, ensures alignment with Hong Kong’s cultural (e.g., filial piety) and policy (e.g., DHC services) contexts, distinguishing it from prior studies [11,12,66].

Additionally, the study generates valuable insights into the operations of the eight data collection centres located in Hong Kong’s Southern District, facilitating effective service matching. Utilizing a social–ecological approach, individual needs are classified into three distinct levels—individual, interpersonal, and community—to guide service provision. This classification process allows for the identification of at-risk groups requiring early intervention and supports the tailoring of services to meet their specific needs, such as pain management, fall prevention, and chronic illness management. For organizational purposes, the study analyzes the strengths of each centre’s service offerings and explores areas for improvement using aggregated data, with a particular focus on critical health domains like pain management, fall prevention, and chronic illness management. By leveraging this comprehensive dataset, the study seeks to enhance the quality and effectiveness of services provided by these centres, ultimately improving the overall well-being of the community-dwelling older adults they serve.

The study also adopts a community participatory approach by sharing layperson-friendly data results with volunteers, equipping them with an enhanced understanding of community health risks. These volunteers play an active role in deciding appropriate intervention strategies and disseminating health messages to the broader community, fostering a collaborative environment. This approach serves as a vehicle for mutual learning between researchers and community members and promotes health equity by ensuring community input. The cyclical and iterative nature of this process, involving regular feedback loops such as annual community reviews, is designed to achieve a beneficial balance between research and actionable outcomes, fostering a long-term commitment to improving services for older adults. By actively involving community members, the study promotes community health and builds a more inclusive community framework. This participatory model not only empowers volunteers but also ensures that interventions are culturally relevant and tailored to the specific needs of the community, leading to more sustainable and impactful health outcomes [66].

Methodological Considerations

Initial data reveals that over 70% of participants are female, reflecting their predominant use of community centres as a primary resource. To address the gender imbalance and improve representativeness, the collaborating NGO’s outreach team will intensify the recruitment of older men by tailoring messages to men’s health interests (e.g., cardiovascular health), training male volunteers as peer ambassadors, and engaging in venues frequented by older men (e.g., tea houses, parks, and chess clubs), while accommodating accessibility needs to encourage membership and participation. The results from this relatively affluent, urban district may not generalize to other places, so the sample is less representative than a territory-wide cohort; however, focusing on one district yields more detailed, context-specific insights into local ageing needs. This district-level analysis serves as an informative case study, offering valuable insights into local health dynamics. Moreover, the risks caused by the representativeness problem (e.g., skewed toward socially engaged, older, female, and lower-income people) can be addressed by several strategies, such as statistical adjustments, sensitivity analyses, targeted recruitment, and transparent reporting. Furthermore, the administrative data collection model employed in this study holds potential for adaptation and application to other communities across Hong Kong and beyond, contributing to a more complete understanding of population health when scaled up. Recognizing attrition as an inherent challenge in longitudinal social survey research, we will reduce loss to follow-up through the aforementioned structured retention plan. Moreover, the study’s emphasis on a district-level administrative data collection model helps manage this issue effectively. The collaborating NGO’s well-established and conventional outreach services, such as regular contact and support programmes, are expected to mitigate the impact of participant dropout by maintaining engagement over time. This approach leverages existing infrastructure to sustain participation rates. In conclusion, by addressing these methodological considerations—gender imbalance, limited generalizability, and attrition—the study enhances our understanding of the complex biological and psychological processes that influence HRQoL among community-dwelling older people from a longitudinal perspective. These adjustments ensure the provision of robust and actionable insights, informing future research, policy development, and practical applications in geriatric care.

Author Contributions

V.W.L. and H.H.L. conceptualized and designed the study. H.H.L., S.X. and V.W.L. wrote and edited the manuscript. V.W.L., H.H.L. and S.X. supervised and administered the study. H.H.L. and S.X. equally contributed to the study. A.N.T.W. and T.B.T.L. managed data collection. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Aberdeen Kai-fong Welfare Association. The funder played a role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has obtained ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at The University of Hong Kong (HREC Reference Number: EA240623). The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for the publication of their data was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aberdeen Kai-fong Welfare Association for supporting this project and all the participants who completed the questionnaires.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lewis, C.; Buffel, T. Aging in place and the places of aging: A longitudinal study. J. Aging Stud. 2020, 54, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani-Harreman, K.E.; Bours, G.J.J.W.; Zander, I.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; van Duren, J.M.A. Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’: A scoping review. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 2026–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, E.W.-T. A review of ageing in place: Policies and initiatives in Hong Kong since 2010. In Ageing in Place: Design, Planning and Policy Response in the Western Asia-Pacific; Judd, B., Tanoue, K., Liu, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, D.; Walsh, K. Ageing in place. In Handbook on Migration and Ageing; Torres, S., Hunter, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Vanleerberghe, P.; De Witte, N.; Claes, C.; Schalock, R.L.; Verté, D. The quality of life of older people aging in place: A literature review. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, K.; Kozlowski, D.; Horstmanshof, L. Experiences of ageing in place in Australia and New Zealand: A scoping review. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 33, 623–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Farré, C.; Malagón-Aguilera, M.C.; Ballester-Ferrando, D.; Bertran-Noguer, C.; Bonmatí-Tomàs, A.; Gelabert-Vilella, S.; Juvinyà-Canal, D. Healthy ageing in place: Enablers and barriers from the perspective of the elderly. A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life [Internet]. Available online: https://www-who-int.eproxy.lib.hku.hk/toolkits/whoqol (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Patrick, D.L.; Erickson, P. Health Status and Health Policy: Quality of Life in Health Care Evaluation and Resource Allocation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans, C.E.; Zerwic, J.J.; Wilbur, J.E.; Larson, J.L. Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2005, 37, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqeca, F.; Yip, O.; Mendieta, M.J.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Zeller, A.; De Geest, S.; Zúñiga, F.; Stenz, S.; Briel, M.; Quinto, C.; et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among home-dwelling older adults aged 75 or older in Switzerland: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, A.T.Y.; Choi, K.C.; Lee, D.T.F.; Yu, D.S.F.; Ng, W.M. Application of a health-related quality of life conceptual model in community-dwelling older Chinese people with diabetes to understand the relationships among clinical and psychological outcomes. J. Diabetes Investig. 2014, 5, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, E.-Y.; Park, Y.-H.; Cho, B.; Huh, I.; Lim, K.-C.; Ryu, S.I.; Han, A.-R.; Lee, S. Effectiveness of a community-based integrated service model for older adults living alone: A nonrandomized prospective study. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimou, C.; Harel, M.; Laubarie-Mouret, C.; Cardinaud, N.; Charenton-Blavignac, M.; Toumi, N.; Trimouillas, J.; Gayot, C.; Boyer, S.; Hebert, R.; et al. Patterns and predictive factors of loss of the independence trajectory among community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, E.; Zoli, M.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Salive, M.E.; Studenski, S.A.; Ferrucci, L. Aging and multimorbidity: New tasks, priorities, and frontiers for integrated gerontological and clinical research. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Walker, A. The impact of community care services on the preference for ageing in place in urban China. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, R.; Playford, C.J.; Gayle, V.; Dibben, C. The role of administrative data in the big data revolution in social science research. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 59, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollard, M. Administrative data: Problems and benefits. A perspective from the United Kingdom. In Facing the Future: European Research Infrastructures for the Humanities and Social Sciences; Duşa, A., Nelle, D., Stock, G., Wagner, G.G., Eds.; SCIVERO Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Laugesen, K.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Schmidt, M.; Gissler, M.; Valdimarsdottir, U.A.; Lunde, A.; Sørensen, H.T. Nordic health registry-based research: A review of health care systems and key registries. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 13, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.T.T.; Huang, L.; Chui, C.S.L.; Wan, E.Y.F.; Li, X.; Wong, C.K.H.; Chan, E.W.W.; Ma, T.; Lum, D.H.; Leung, J.C.N.; et al. Multimorbidity and adverse events of special interest associated with Covid-19 vaccines in Hong Kong. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Luo, H.; Wong, G.H.Y.; Tang, J.Y.M.; Lam, T.-C.; Wong, I.C.K.; Yip, P.S.F. Risk of self-harm after the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in Hong Kong, 2000–2010: A nested case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census and Statistics Department. Hong Kong Population Projections 2020–2069; Census and Statistics Department: Hong Kong, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone, D.; Wendin, K.; Kremer, S.; Frøst, M.B.; Bredie, W.L.; Olsson, V.; Otto, M.H.; Skjoldborg, S.; Lindberg, U.; Risvik, E. Health and quality of life in an aging population–Food and beyond. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 47, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, E.; Kwok, T.T.Y.; Sumerlin, T.S.; Goggins, W.B.; Leung, J.; Kim, J.H. Does subjective social status predict depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly? A longitudinal study from Hong Kong. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Sha, F.; Chan, C.H.; Yip, P.S.F. Validation of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale (“LSNS-6”) and its associations with suicidality among older adults in China. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0201612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Census and Statistics Department. 2021 Population Census Thematic Report: Older Persons; Census and Statistics Department: Hong Kong, 2022. Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1120118/att/B11201182021XXXXB0100.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Yu, R.; Wong, M.; Chong, K.C.; Chang, B.; Lum, C.M.; Auyeung, T.W.; Lee, J.; Lee, R.; Woo, J. Trajectories of frailty among Chinese older people in Hong Kong between 2001 and 2012: An age-period-cohort analysis. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SWD Elderly Information Website. Introduction of Long Term Care Services [Internet]. Available online: https://www.swd.gov.hk/en/pubsvc/elderly/cat_residentcare/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Health Bureau. Develop a Community-Based Primary Healthcare System [Internet]. Available online: https://www.primaryhealthcare.gov.hk/bp/en/supplementary-documents/develop-a-community-based-system/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Mesthrige, J.W.; Cheung, S.L. Critical evaluation of ‘ageing in place’ in redeveloped public rental housing estates in Hong Kong. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2006–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, T.Y.; Lou, V.W.; Chen, Y.; Wong, G.H.; Luo, H.; Tong, T.L. Neighborhood support and aging-in-place preference among low-income elderly Chinese city-dwellers. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.W.-N.; Kwok, S.S.-T.; Luk, F.W.-Y. Perceptions of the elderly on ageing in place in Hong Kong. SpringerPlus 2015, 4 (Suppl. S2), O4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jagosh, J.; Bush, P.L.; Salsberg, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Cargo, M.; Green, L.W.; Herbert, C.P.; Pluye, P. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popay, J.; Whitehead, M.; Ponsford, R.; Egan, M.; Mead, R. Power, control, communities and health inequalities I: Theories, concepts and analytical frameworks. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, N.S.; Sereika, S.M.; Albrecht, S.A.; Terry, M.A.; Erlen, J.A. Testing a model of health-related quality of life in women living with HIV infection. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.; Pozehl, B.; Hertzog, M.; Zimmerman, L.; Riegel, B. Predictors of overall perceived health in patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.M.; Mayo, N.E.; Gagnon, B. Independent contributors to overall quality of life in people with advanced cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2013, 108, 1790–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liira, H.; Mavaddat, N.; Eineluoto, M.; Kautiainen, H.; Strandberg, T.; Suominen, M.; Laakkonen, M.L.; Eloniemi-Sulkava, U.; Sintonen, H.; Pitkälä, K. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality in heterogeneous samples of older adults. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 9, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, T.; McLennon, S.M.; Carpenter, J.S.; Buelow, J.M.; Otte, J.L.; Hanna, K.M.; Ellett, M.L.; A Hadler, K.; Welch, J.L. Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangchan, C.; Matthews, A.K. Application of Ferrans et al.’s conceptual model of health—Related quality of life: A systematic review. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubritsky, C.; Abbott, K.M.; Hirschman, K.B.; Bowles, K.H.; Foust, J.B.; Naylor, M.D. Health-related quality of life: Expanding a conceptual framework to include older adults who receive long-term services and supports. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, S.W.; Silvia, S.R.M. Changes in attitudes among children and elderly adults in intergenerational group work. Educ. Gerontol. 2000, 26, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Y.-M.; Ho, A.H.-Y.; Luo, H.; Wong, G.H.-Y.; Lau, B.H.-P.; Lum, T.Y.-S.; Cheung, K.S.-L. Validating a Cantonese short version of the Zarit Burden Interview (CZBI-Short) for dementia caregivers. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.L.-Y.P.; Cheung, A.W.-L.M.; Wong, A.Y.-K.M.; Xu, R.H.P.; Ramos-Goñi, J.M.P.; Rivero-Arias, O.D. Normative profile of health-related quality of life for Hong Kong general population using preference-based instrument EQ-5D-5L. Value Health 2019, 22, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census and Statistics Department. 2021 Population Census: Summary Results; Census and Statistics Department: Hong Kong, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department. Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report 2020; Census and Statistics Department: Hong Kong, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.L.; Zhang, Y.; Ng, K.H.; Wong, H.; Lee, J.W.Y. Living environment and quality of life in Hong Kong. Asian Geogr. 2018, 35, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing Bureau. Housing in Figures 2022; Housing Bureau: Hong Kong, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coretti, S.; Ruggeri, M.; McNamee, P. The minimum clinically important difference for EQ-5D index: A critical review. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2014, 14, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, M.D.; Brayne, C.E.; Matthews, F.E. A systematic literature review of attrition between waves in longitudinal studies in the elderly shows a consistent pattern of dropout between differing studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Oteng, S.A. Gerontechnology for better elderly care and life quality: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Ageing 2023, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, S.; Youssef, G.J.; Macdonald, J.A.; Sciberras, E.; Shatte, A.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Greenwood, C.; McIntosh, J.; Olsson, C.A.; Hutchinson, D. SEED Lifecourse Sciences Theme Bant Sharyn Barker Sophie Booth Anna Capic Tanja Di Manno Laura Gulenc Alisha Le Bas Genevieve Letcher Primrose Lubotzky Claire Ann Opie Jessica O’Shea Melissa Tan Evelyn Williams Jo. Retention strategies in longitudinal cohort studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Provencher, V.; Mortenson, W.B.; Tanguay-Garneau, L.; Bélanger, K.; Dagenais, M. Challenges and strategies pertaining to recruitment and retention of frail elderly in research studies: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 59, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Yiu, S.; Nasreddine, Z.; Leung, K.-T.; Lau, A.; Soo, Y.O.Y.; Wong, L.K.-S.; Mok, V. Validity and reliability of two alternate versions of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Hong Kong version) for screening of Mild Neurocognitive Disorder. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Stewart, S.M.; Wong, P.T.K.; Lam, T.H. Screening for depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) among the general population in Hong Kong. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 134, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.Y.C.; Man, D.W.K. The validation of the Hong Kong Chinese version of the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale for institutionalized elderly persons. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2002, 22, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Chui, W.H.; Kwok, Y.Y. The Volunteer Satisfaction Index: A validation study in the Chinese cultural context. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mansfield, A.K.; Keitner, G.I.; Sheeran, T. The Brief Assessment of Family Functioning Scale (BAFFS): A three-item version of the General Functioning Scale of the Family Assessment Device. Psychother. Res. 2019, 29, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, M.J.; Barker, E.; Nechvatal, J.R.; Foti, J.; Bassham, L.E.; Roback, E.; Dray, J.F., Jr. Advanced Encryption Standard (AES); National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, Hong Kong. Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Cap. 486). 2024. Available online: https://www.pcpd.org.hk/english/data_privacy_law/ordinance_at_a_Glance/ordinance.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.J. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, M. Community-Based Participatory Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).