Promoting Healthy Aging Through Mindfulness and Yoga: A Systematic Review of Interventions for People Living with HIV Who Use Drugs or Who Have a History of Substance Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

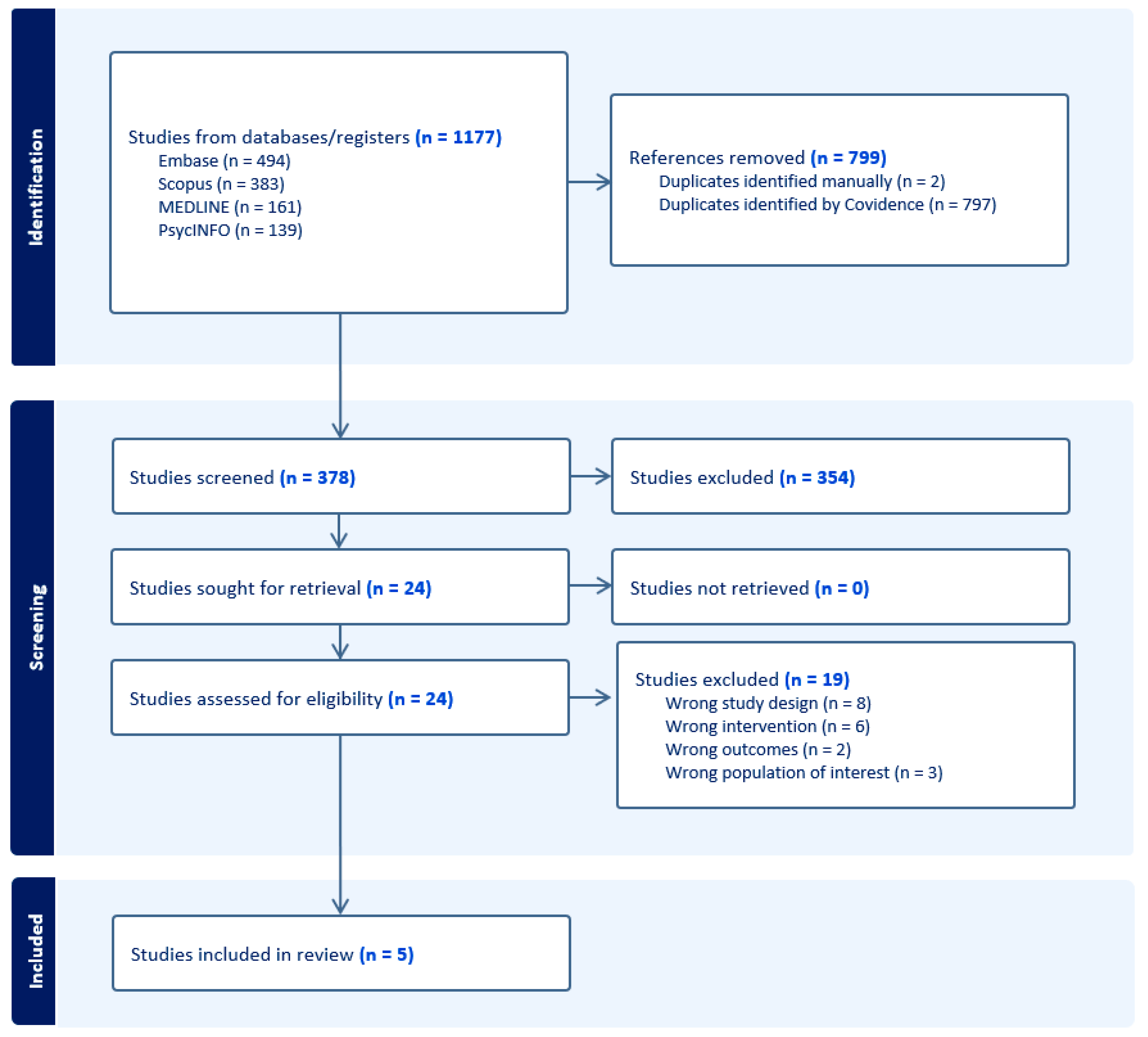

3.1. Results of the Literature Search

3.2. Risk of Bias Estimation

| Author | Substance | Sample | Study Design/Setting | Intervention | Substance Use Outcome | Healthy Aging Outcome | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agarwal et al. (2015) [53] | Crack cocaine | N = 24 | RCT; assessed at baseline, 2 and 4 months in Miami | Yoga/meditation | Not reported | ↓ PSS post-intervention vs. baseline (MD = 4.7, p < 0.05); ↓ IES intrusion at post (MD = 7.8, p < 0.05) & follow-up (MD = 5.4, p < 0.05) | Reduction in perceived stress and trauma-related symptoms |

| Cioe et al. (2023) [54] | Cigarettes | N = 16 | 8-week single-group pilot | 30-day Unwinding Anxiety app | ↑ Readiness to quit at week 4 (b = 0.56, p = 0.002), not significant at week 8 (b = 0.34, p = 0.30) | ↓ Anxiety at week 4 (b = −5.5, p = 0.004) & week 8 (b = −5.1, p = 0.008) | Improved anxiety symptoms, slight gain in readiness to quit |

| Luoma et al. (2023) [50] | Injection drugs | N = 100 | RCT at harm reduction NGO in Russia | ACT-based stigma reduction group | No group differences in drug use at 1 mo (MD = 0.00, p = 1.0) or 6 mo (MD = −3.33, p = 0.210); ↑ ART initiation (PD = 0.17, p = 0.005) | No difference in HIV stigma (AMD = 0.40, p = 0.14); ↑ treatment use (PD = 0.17–0.21, p = 0.008–.017) | No change in drug use; improved linkage to HIV and substance use treatment |

| Magidson et al. (2021) [51] | Alcohol & other drugs | N = 61 | Hybrid RCT in South Africa | Khanya (peer-delivered behavioral intervention) | ↓ PEth (t = 4.16, p = 0.01); ↓ high-risk WHO-ASSIST category 30–40 pts | ↑ ART adherence (t = +6.4% Khanya vs. −22.3% ETAU, p < 0.05); adherence linked to suppression (t = 2.31, p = 0.02) | Reduced substance use risk; improved ART adherence |

| Wimberly et al. (2018) [52] | Substances (various) | N = 73 | RCT; reentry program clients | 12-session Hatha yoga | ↓ Substance use in yoga group vs. TAU at 1–3 mo (χ2 = 11.13, p < 0.001) | ↓ Stress at 3 mo in yoga group (F = 9.24, p < 0.05) | Yoga reduced stress and substance use in returning citizens |

3.3. Study Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trickey, A.; Sabin, C.A.; Burkholder, G.; Crane, H.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; Egger, M.; Gill, M.J.; Grabar, S.; Guest, J.L.; Jarrin, I.; et al. Life expectancy after 2015 of adults with HIV on long-term antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America: A collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e295–e307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, F.; Lodwick, R.K.; Smith, C.J.; Smith, R.; Cambiano, V.; Lundgren, J.D.; Delpech, V.; Phillips, A.N. Projected life expectancy of people with HIV according to timing of diagnosis. AIDS 2012, 26, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wing, E.J. The aging population with HIV infection. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2017, 128, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet, N.; Winter, M.R.; Heeren, T.; Walley, A.Y.; Saitz, R. Polysubstance Use Patterns Associated With HIV Disease Severity Among Those with Substance Use Disorders: A Latent Class Analysis. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2023, 84, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzler, B.; Dombrowski, J.C.; Crane, H.M.; Eron, J.J.; Geng, E.H.; Christopher Mathews, W.; Mayer, K.H.; Moore, R.D.; Mugavero, M.J.; Napravnik, S.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Substance Use Disorders Among HIV Care Enrollees in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, S.; Arpadi, S.M.; Yin, M.T.; Martins, S.S. Patterns of drug use and HIV infection among adults in a nationally representative sample. Addict. Behav. 2017, 68, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Neelamegam, M.; Rajasuriar, R. Ageing with HIV: Health implications and evolving care needs. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durvasula, R.; Miller, T.R. Substance abuse treatment in persons with HIV/AIDS: Challenges in managing triple diagnosis. Behav. Med. 2014, 40, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, K.; Afzal, S.; Daood, M.; Siddiqui, M. Substance abuse and mental health issues among HIV/AIDS patients. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2023, 33, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2020—Seizing the Moment: Tackling Entrenched Inequalities to End Epidemics. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 2020. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/global-aids-report (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Korenromp, E.L.; Sabin, K.; Stover, J.; Brown, T.; Johnson, L.F.; Martin-Hughes, R.; Ten Brink, D.; Teng, Y.; Stevens, O.; Silhol, R.; et al. New HIV Infections Among Key Populations and Their Partners in 2010 and 2022, by World Region: A Multisources Estimation. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2024, 95, e34–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhabokritsky, A.; Clarke, R.; Rosenes, R.; Smith, G.; Loutfy, M.; Andany, N.; Falutz, J.; Klein, M.; Harris, M.; Guillemi, S.; et al. Correlates of Healthy Aging in Geriatric HIV (CHANGE HIV)-CTN 314. Viruses 2023, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webel, A.R.; Schexnayder, J.; Cioe, P.A.; Zuñiga, J.A. A Review of Chronic Comorbidities in Adults Living With HIV: State of the Science. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2021, 32, 322–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.J.; Adeagbo, O. HIV and Aging: Double Stigma. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2021, 8, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiau, S.; Bender, A.A.; O’Halloran, J.A.; Sundermann, E.; Aggarwal, J.; Althoff, K.N.; Baker, J.V.; Deeks, S.; Fried, L.P.; Karpiak, S.; et al. The Current State of HIV and Aging: Findings Presented at the 10th International Workshop on HIV and Aging. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2020, 36, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, D.E.; Blake, B.J.; Brennan-Ing, M.; DeMarco, R.F.; Fazeli, P.L.; Relf, M.V. Revisiting successful aging with HIV through a revised biopsychosocial model: An update of the literature. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2019, 30, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, H.; Sanchez, M.; Bautista, T.; Cox, R. Social vulnerabilities for substance use: Stressors, socially toxic environments, and discrimination and racism. Neuropharmacology 2021, 188, 108518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stall, R.; Mills, T.C.; Williamson, J.; Hart, T.; Greenwood, G.; Paul, J.; Pollack, L.; Binson, D.; Osmond, D.; Catania, J.A. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, O.T.; Wang, K.; Chandler, R.; Melton, P.A.; Truong, D.N. A descriptive analysis of concurrent alcohol and substance use among patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection. Soc. Work. Health Care 2020, 59, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloner, B.; Li, W.; Flores, M.; Progovac, A.M.; Lê Cook, B. A Widening Divide: Cigarette Smoking Trends Among People with Substance Use Disorder and Criminal Legal Involvement. Health Aff. 2023, 42, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, S.; Kall, M.; Nichols, B.E.; Stempher, E.; Versteegh, L.; van de Vijver, D.A.M.C.; van Sighem, A.; Versteegh, M.; Boucher, C.; Delpech, V.; et al. Quality of life among people living with HIV in England and the Netherlands: A population-based study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 8, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dove-Medows, E.; Knox, J.; Valentine-Graves, M.; Sullivan, P. “I can’t afford it right now, so it doesn’t matter”: Structural drivers of viral suppression among men who have sex with men: A longitudinal qualitative approach. Res. Sq. 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidala, A.A.; Wilson, M.G.; Shubert, V.; Gogolishvili, D.; Globerman, J.; Rueda, S.; Bozack, A.K.; Caban, M.; Rourke, S.B. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, e1–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.L.; Gilman, S.E.; Cheng, T.L.; Drury, S.S.; Hill, C.V.; Geronimus, A.T. Life Course Approaches to the Causes of Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, S48–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, E.C.; Sehl, M.E.; Shih, R.; Langfelder, P.; Wang, R.; Horvath, S.; Bream, J.H.; Duggal, P.; Martinson, J.; Wolinsky, S.M.; et al. Accelerated aging with HIV begins at the time of initial HIV infection. iScience 2022, 25, 104488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodés, B.; Cadiñanos, J.; Esteban-Cantos, A.; Rodríguez-Centeno, J.; Arribas, J.R. Ageing with HIV: Challenges and biomarkers. EBioMedicine 2022, 77, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, H.L.; Aghvinian, M.; Gouse, H.; Robbins, R.N.; Brew, B.J.; Mao, L.; Cysique, L.A. Is there any evidence of premature, accentuated and accelerated aging effects on neurocognition in people living with HIV? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 917–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.P.; Iudicello, J.E.; Morgan, E.E.; Kamat, R.; Clark, L.R.; Avci, G.; Bondi, M.W.; Woods, S.P.; The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. Accelerated and accentuated neurocognitive aging in HIV infection. J. Neurovirology 2017, 23, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.; Zhang, W.; Moore, D.; Salters, K.; Trigg, J.; Wesseling, T.; Parashar, S.; McLinden, T.; Sereda, P.; McDougall, P.; et al. Impacts of overdose and socio-structural factors on recent mortality among people with HIV in British Columbia, Canada. AIDS 2025, 39, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, B.D.; Neufeld, S.D.; Butler, A.; Bonn, M.; Zakimi, N.; Farrell, J.; Greer, A. “Criminalization Causes the Stigma”: Perspectives from People Who Use Drugs. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2023, 50, 402–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Mehta, S.H.; Astemborski, J.; Piggott, D.A.; Genberg, B.L.; Woodson-Adu, T.; Benson, E.M.; Thomas, D.L.; Celentano, D.D.; Vlahov, D.; et al. Mortality among people who inject drugs: A prospective cohort followed over three decades in Baltimore, MD, USA. Addiction 2022, 117, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Health, Rights and Drugs: Harm Reduction, Decriminalization and Zero Discrimination for People Who Use Drugs. 2019. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/JC2954_UNAIDS_drugs_report_2019 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Parashar, S.; Collins, A.B.; Montaner, J.S.; Hogg, R.S.; Milloy, M.J. Reducing rates of preventable HIV/AIDS-associated mortality among people living with HIV who inject drugs. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2016, 11, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helleberg, M.; Gerstoft, J.; Afzal, S.; Kronborg, G.; Larsen, C.S.; Pedersen, C.; Bojesen, S.E.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Obel, N. Risk of cancer among HIV-infected individuals compared to the background population: Impact of smoking and HIV. AIDS 2014, 28, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Trombka, M.; Lovas, D.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Vago, D.R.; Gawande, R.; Dunne, J.P.; Lazar, S.W.; Loucks, E.B.; Fulwiler, C. Mindfulness and Behavior Change. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaeghen, P.; Aikman, S.N.; Mirabito, G. Mindfulness Interventions in Older Adults for Mental Health and Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2025, 80, gbae205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain-Zaragoza, S.; Prakash, R.S. Mindfulness Training for Healthy Aging: Impact on Attention, Well-Being, and Inflammation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Nikolaou, G. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in clinical practice: A systematic review of neurocognitive outcomes and applications for mental health and well-being. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, A.; Bombell, H.; Dean, C.; Tiedemann, A. Yoga-based exercise improves health-related quality of life and mental well-being in older people: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, L.; Hempel, S.; Ewing, B.A.; Apaydin, E.; Xenakis, L.; Newberry, S.; Colaiaco, B.; Maher, A.R.; Shanman, R.M.; Sorbero, M.E.; et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, J.T.; Sharma, B.; Javandel, S.; Moran, P.; Paul, R.; De Gruttola, V.; Tomov, D.; Azmy, H.; Sandoval, R.; Hillis, M.; et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for symptom management in older individuals with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. AIDS Behav. 2024, 28, 1811–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, O.R.; Peters, G.Y.; Bakker, C.J.; Carlsson, R.; Coles, N.A.; Corker, K.S.; Feldman, G.; Moreau, D.; Nordström, T.; Pickering, J.S.; et al. Increasing the transparency of systematic reviews: Presenting a generalized registration form. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 1–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abud, T.; Kounidas, G.; Martin, K.R.; Werth, M.; Cooper, K.; Myint, P.K. Determinants of healthy ageing: A systematic review of contemporary literature. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panayi, M.; Charalambous, G.K.; Jelastopulu, E. Enhancing quality of life and medication adherence for people living with HIV: The impact of an information system. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2024, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, J.B.; Rossi, S.L.; Sereda, Y.; Pavlov, N.; Toussova, O.; Vetrova, M.; Bendiks, S.; Kiriazova, T.; Krupitsky, E.; Lioznov, D.; et al. An acceptance-based, intersectional stigma coping intervention for people with HIV who inject drugs: A randomized clinical trial. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 28, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magidson, J.F.; Joska, J.A.; Belus, J.M.; Andersen, L.S.; Regenauer, K.S.; Rose, A.L.; Myers, B.; Majokweni, S.; O’Cleirigh, C.; Safren, S.A. Project Khanya: Results from a pilot randomized type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of a peer-delivered behavioural intervention for ART adherence and substance use in HIV care in South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24 (Suppl. S2), e25720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberly, A.S.; Engstrom, M.; Layde, M.; McKay, J.R. A randomized trial of yoga for stress and substance use among people living with HIV in reentry. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2018, 94, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.P.; Kumar, A.; Lewis, J.E. A pilot feasibility and acceptability study of yoga/meditation on the quality of life and markers of stress in persons living with HIV who also use crack cocaine. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2015, 21, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioe, P.A.; Sokolovsky, A.W.; Brewer, J.A.; Kahler, C.W. App-delivered mindfulness training to reduce anxiety in people with HIV who smoke: A one-armed feasibility trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhivanan, P.; Krupp, K.; Waechter, R.; Shidhaye, R. Yoga for Healthy Aging: Science or Hype? Adv. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2021, 3, e210016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, V.; Clatworthy, J.; Harding, R.; Whetham, J.; Emerge Consortium. Measuring quality of life among people living with HIV: A systematic review of reviews. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, D.; Anderson, J.; Catalan, J.; Delpech, V.; Ridge, D. How older people living with HIV narrate their quality of life: Tensions with quantitative approaches to quality-of-life research. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2021, 1, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Calasanti, T. Critical perspectives on successful aging: Does it “appeal more than it illuminates”? Gerontologist 2015, 55, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.; Cahill, S. Barriers and opportunities for the mental health of LGBT older adults and older people living with HIV: A systematic literature review. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbre, V.; Oswald, A.; Jen, S. Queer gerontology: Principles for advancing rigor and justice. Gerontologist 2025, 65, gnaf112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliotti, V.; Taggart, T.; Walker, M.; Kusmastuti, S.; Ransome, Y. Religion, faith, and spirituality influences on HIV prevention activities: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo-Jeong, M.; Lacroix-Williamson, L.; Mejía, D.S.C.; Yom, T.; Kim, M.; Lincoln, A.K. Experiences and Perceptions of Social Connection Among Minoritized Older Adults with HIV During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2024, 50, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggott, D.A.; Mehta, S.H.; Rubin, L.H.; Sun, J.; Leng, S.X.; Kirk, G.D. Cognitive function and mortality among persons aging with HIV and injection drug use. AIDS 2025, 39, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryer, C.; Lodge, W.; 2nd Goulet, P.; Baldwin, J.A. “A tricky dance”: Ryan White service experiences among American Indian/Alaska Native Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2025, 29, 2243–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacht, C.L.; Lentz, C.; Vincent, W.; Siconolfi, D.; Pollack, L.M.; Kegeles, S.M.; Campbell, C.K.; Ogunbajo, A.; Storholm, E.D. Untangling discrimination: The impact of internalizing oppression on HIV treatment engagement among young Black sexual minority men in the Southern US. AIDS Behav. 2025, 29, 3264–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sophus, A.I.; Mitchell, J.W. Reducing HIV risk behaviors among Black women living with and without HIV/AIDS in the U.S.: A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 732–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data 2019. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 2019. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Kemp, C.G.; Edwards, A.J.; White, L.; Kore, G.; Thurman, P.J.; Gaines, T.; King, P.T.; Cole, M.; Orellana, E.R. Implementation Science for HIV Prevention and Treatment in Indigenous Communities: A Systematic Review and Commentary. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2024, 21, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K.; Sanders, C.; Petroll, A.E. “HIV Is Not Going to Kill Me, Old Age Is!”: The Intersection of Aging and HIV for Older HIV-Infected Adults in Rural Communities. AIDS Educ. Prev. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. AIDS Educ. 2017, 29, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, W., 2nd; Rawat, S.; Dange, A.; Agénor, M.; Anand, V.R.; Operario, D.; Mimiaga, M.J.; Biello, K.B. Transgender women in India: A syndemic and intersectional framework addressing HIV care gaps. Am. J. Public Health 2025, 115, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emlet, C.A.; Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I.; Kim, H.J.; Jung, H. Accounting for HIV Health Disparities: Risk and Protective Factors Among Older Gay and Bisexual Men. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.L.; Rupasinghe, D.; Chanyachukul, T.; Crabtree Ramírez, B.; Murenzi, G.; Kwobah, E.; Mureithi, F.; Minga, A.; Marbaniang, I.; Perazzo, H.; et al. Comorbidities and HIV-related factors associated with mental health symptoms and unhealthy substance use among older adults living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2025, 28, e26434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.B.; Strike, C.; Guta, A.; Baltzer Turje, R.; McDougall, P.; Parashar, S.; McNeil, R. “We’re giving you something so we get something in return”: Perspectives on research participation and compensation among people living with HIV who use drugs or have a history of drug use. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 39, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, P.; Perkins, M. The silent majority: Aging with HIV. Innov. Aging 2021, 5 (Suppl. S1), 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, C.M.; Cooper, H.L.; Williams, D.R.; Emmons, K.M. Walking the talk on multi-level interventions: The power of parsimony. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 283, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deren, S.; Cortes, T.; Dickson, V.V.; Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Han, B.H.; Karpiak, S.; Naegle, M.; Ompad, D.C.; Wu, B. Substance Use Among Older People Living With HIV: Challenges for Health Care Providers. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Cascio, M.; Anderson, J.; Pasanen, S.; Harding, R. A person-centred approach to enhance the long-term health and wellbeing of people living with HIV in Europe. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2023, 26 (Suppl. S1), e26117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, A. From punitive to proactive: An alternative approach for responding to HIV criminalization that departs from penalizing marginalized communities. Hastings J. Gend. Law 2013, 24, 363–403. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski, J.C.; Corcorran, M.A.; Carney, T.; Parczewski, M.; Gandhi, M. The impact of homelessness and housing insecurity on HIV. Lancet HIV 2025, 12, e449–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, E.S.; Creasy, S.L.; Townsend, J.; Hawk, M. A qualitative exploration of health care workers’ approaches to relational harm reduction in HIV primary care settings. Harm. Reduct. J. 2024, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bryer, C.M.; Stang, G.S.; Collins, A.B.; Haygood, L.N.; Blu Wakpa, T.; Proulx, J. Promoting Healthy Aging Through Mindfulness and Yoga: A Systematic Review of Interventions for People Living with HIV Who Use Drugs or Who Have a History of Substance Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111685

Bryer CM, Stang GS, Collins AB, Haygood LN, Blu Wakpa T, Proulx J. Promoting Healthy Aging Through Mindfulness and Yoga: A Systematic Review of Interventions for People Living with HIV Who Use Drugs or Who Have a History of Substance Use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111685

Chicago/Turabian StyleBryer, Chase M., Garrett S. Stang, Alexandra B. Collins, Laura N. Haygood, Tria Blu Wakpa, and Jeffrey Proulx. 2025. "Promoting Healthy Aging Through Mindfulness and Yoga: A Systematic Review of Interventions for People Living with HIV Who Use Drugs or Who Have a History of Substance Use" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111685

APA StyleBryer, C. M., Stang, G. S., Collins, A. B., Haygood, L. N., Blu Wakpa, T., & Proulx, J. (2025). Promoting Healthy Aging Through Mindfulness and Yoga: A Systematic Review of Interventions for People Living with HIV Who Use Drugs or Who Have a History of Substance Use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111685