Wondering Awe Is the Mediator of the Link Between Experience of Nature and Psychological Wellbeing—Relevance for Public Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nature-Relatedness, Experience of Nature, and Psychological Health

1.2. Feelings of Wondering Awe in Nature

1.3. Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of Participants

2.2. Sociodemographic Data

2.3. Standardized Measures

2.3.1. Experience of Nature

2.3.2. Nature Relatedness

2.3.3. Awe and Gratitude

2.3.4. Gratitude

2.3.5. Wellbeing

2.3.6. Activities

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Description of Participants

3.2. Intensity of Nature Perceptions

3.3. Correlations Between Nature Perceptions, Awe/Gratitude, Wellbeing, and Activities

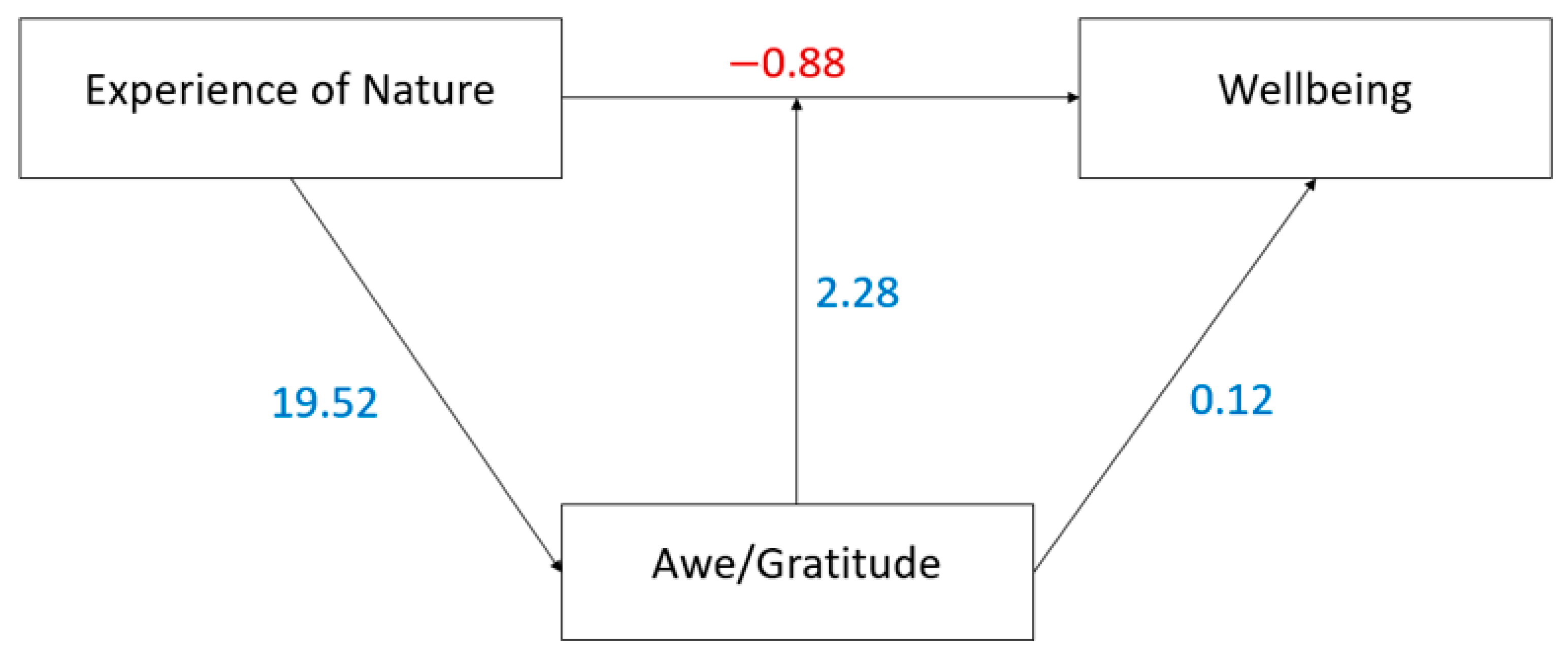

3.4. Mediation Analyses

3.5. Predictors of Wellbeing

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Findings

4.2. Implications for Public Health

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ENS | Experience of nature |

| WHO-5 | WHO-Five Wellbeing Index |

References

- Antonelli, M.; Barbieri, G.; Donelli, D. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, E.; Fiedler, H.; Wittmann, M. Increased relaxation and present orientation after a period of silence in a natural surrounding. Nordic J. Music. Ther. 2020, 29, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Baumann, K. Experience of nature and times of silence as a resource to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic is mediating the effects of Awe and Gratitude on psychological Wellbeing—Findings from a continuous cross-sectional survey in Germany. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1020053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurly, J.; Walker, G.J. Nature in our lives: Examining the human need for nature relatedness as a basic psychological need. J. Leisure Res. 2019, 50, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A. Spiritual Needs in Research and Practice: The Spiritual Needs Questionnaire as a Global Resource for Health and Social Care; Pelgrave McMillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-70138-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.-Y.; Astell-Burt, T.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Feng, X. Green Space Quality and Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Effects of forest environment (Shinrin-yoku/Forest bathing) on health promotion and disease prevention—The Establishment of “Forest Medicine”. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2022, 27, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The Nature Relatedness Scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behaviour. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. Nature Relatedness and Subjective Wellbeing. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Wellbeing Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.H.; Shanahan, D.F.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Lin, B.B.; Barber, E.; Franco, L.; Fuller, R.A. Is Nature Relatedness Associated with Better Mental and Physical Health? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 90–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Berg, A.E.; Custers, M.H. Gardening promotes neuroendocrine and affective restoration from stress. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, J.J.; Thompson, C.W.; Aspinall, P.A.; Brewer, M.J.; Duff, E.I.; Miller, D.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A. Green space and stress: Evidence from cortisol measures in deprived urban communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4086–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 575, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerron, G.; Mourato, S. Happiness is greater in natural environments. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; Bolderdijk, J.W. An exploratory study into the effects of extraordinary nature on emotions, mood, and prosociality. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Keijzer, C.; Bauwelinck, M.; Dadvand, P. Long-term exposure to residential greenspace and healthy aging: A Systematic Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Ortiz, M. Validierung eines Fragebogeninstrumentes zur Erfassung des Erlebens von Natur als subjektive Empfindung. Complement. Med. Res. 2024, 31, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A.; McAnirlin, O.; Yoon, H. Where greenspace matters most: A systematic review of urbanicity, greenspace, and physical health. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Howell, R.T.; Iyer, R. Engagement with natural beauty moderates the positive relation between connectedness with nature and psychological Wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A. Wondering Awe as a perceptive aspect of spirituality and its relation to indicators of Wellbeing: Frequency of perception and underlying triggers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 738770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaden, D.B.; Kaufman, S.B.; Hyde, E.; Chirico, A.; Gaggioli, A.; Zhang, J.W.; Kelner, D. The development of the awe experience scale (AWE-S): A multifactorial measure for a complex emotion. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 14, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognit. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Janz, B.; Reinerman, L.; Bockelman, P.; Trempler, J. Liftoff: Towards an exploration of subjective experience. In A Neurophenomenology of Awe and Wonder: Towards a Non-Reductionist Cognitive Science; Palgrave-Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.B.; Gruber, J.; Keltner, D. Comparing spiritual transformations and experiences of profound beauty. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2010, 2, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J.; Fayn, K.; Nusbaum, E.C.; Beaty, R.E. Openness to experience and awe in response to nature and music: Personality and profound aesthetic experiences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, S.; Borja, Á.; Fleming, L.E.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; White, M.P.; Uyarra, M.C. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, S.M.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A.; Helbich, M.; James, P. Nature’s contributions in coping with a pandemic in the 21st century: A narrative review of evidence during COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 55095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N.; Hayward, R.D. Assessing whether practical wisdom and awe of god are associated with life satisfaction. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2015, 7, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Baumann, K. Validation of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire and Its Association with Disposition of Gratefulness. Religions 2018, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K.; Andrews, S.E.; Sweeny, K. Awe-full uncertainty: Easing discomfort during waiting periods. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 15, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J.; Keltner, D. Appreciation of beauty and excellence. In Character Strengths and Virtues; Peterson, C., Seligman, M.E.P., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 537–551. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, A.M.; Froh, J.J.; Geraghty, A.W. Gratitude and Wellbeing: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. The NR-6: A new brief measure of nature relatedness. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J.A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P.; Olsen, L.R.; Kjoller, M.; Rasmussen, N.K. Measuring Wellbeing rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 mental health subscale and the WHO-Five Wellbeing scale. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 12, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenberghs, G.; Verbeke, G. Multiple Imputation and the Expectation-Maximization Algorithm. In Models for Discrete Longitudinal Data; Molenberghs, G., Verbeke, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Chapter 28; pp. 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furjes-Crawshaw, J.; Heke, I.; Jowett, T.; Rehrer, N.J. The Physical Activity Environment, Nature-Relatedness and Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, S.; Sibinga, E.M.; Gould, N.F.; Rowland-Seymour, A.; Sharma, R.; Berger, Z.; Sleicher, D.; Maron, D.D.; Shihab, H.M.; et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and Wellbeing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotink, R.A.; Hermans, K.S.; Geschwind, N.; De Nooij, R.; De Groot, W.T.; Speckens, A.E. Mindfulness and mood stimulate each other in an upward spiral: A mindful walking intervention using experience sampling. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Williams, J.M.; Morris, P.G.; Chan, S.W.Y. Effectiveness of a mindful nature walking intervention on sleep quality and mood in university students during Covid-19: A randomised control study. Explore 2023, 19, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donovan, H. Mindful Walking: Walk Your Way to Mental and Physical Wellbeing; Hachette Books Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness; Penguin Random House: Westminster, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, S.; Jones, A. Is there evidence that walking groups have health benefits? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.; Vohs, K.D.; Aaker, J. Awe expands people’s perception of time, alters decision making, and enhances Wellbeing. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P.K.; Dietze, P.; Feinberg, M.; Stancato, D.M.; Keltner, D. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Dienberg, T. Attitudes and behaviors related to Franciscan-inspired spirituality and their associations with compassion and altruism in Franciscan brothers and sisters. Religion 2018, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; He, W.; Lu, J. Why are people high in dispositional awe happier? The roles of meaning in life and materialism. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n * | % | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 478 | 100 | |

| Female | 353 | 74 | |

| Male | 120 | 25 | |

| Other/non-binary | 5 | 1 | |

| Mean age (years) | 404 | 51.0 ± 13.0 (19–82) | |

| Educational level | 477 | 100 | |

| None/primary | 8 | 2 | |

| Secondary classes 8–10 | 67 | 14 | |

| Secondary classes 11–13 | 41 | 9 | |

| Evening school/Technical college | 41 | 9 | |

| University of Applied Science/University | 320 | 67 | |

| Partner status | 476 | 100 | |

| With partner | 332 | 70 | |

| Without partner | 144 | 30 | |

| Living area | 485 | 100 | |

| Rural | 214 | 44 | |

| Other/cities | 271 | 56 | |

| Access to green spaces | 483 | 100 | |

| Yes | 272 | 56 | |

| No/insecure | 211 | 44 | |

| Access to green spaces (minutes) | 478 | 5.7 ± 6.4 (0–60) | |

| Attention to nature in the surrounding area | 482 | 100 | 3.1 ± 0.8 (0–4) |

| never/hardly anything | 14 | 3 | |

| moderate | 95 | 20 | |

| much | 211 | 44 | |

| very much | 162 | 34 | |

| Enjoying being outdoors, even in unpleasant weather (NR item 1) | 489 | 100 | 3.1 ± 1.0 (0–4) |

| disagree strongly | 6 | 1 | |

| disagree a little | 41 | 8 | |

| neither agree nor disagree | 46 | 9 | |

| agree a little | 193 | 40 | |

| agree strongly | 203 | 42 | |

| Activities | |||

| cycling outside | 478 | 1.6 ± 1.1 (0–3) | |

| sporting outside | 472 | 1.5 ± 1.0 (0–3) | |

| hiking/strolling | 480 | 2.1 ± 0.7 (0–3) | |

| meditation | 480 | 1.5 ± 1.2 (0–3) | |

| praying | 477 | 1.2 ± 1.3 (0–3) | |

| Psychological Wellbeing (WHO-5) | 490 | 14.9 ± 4.8 (0–25) | |

| Awe/Gratitude (GrAw-7) | 491 | 63.7 ± 18.8 (0–100) |

| Nature Relatedness (NR6) | Experience of Nature (ENS) | ENS—Everyday Detachment/Relaxation | ENS—Fascination with Nature/Wondering | ENS—Sense of Responsibility for Nature | Awe/Gratitude (GrAw-7) | Wellbeing (WHO-5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (n = 474) | mean | 3.07 | 3.35 | 3.29 | 3.45 | 3.28 | 63.82 | 14.91 |

| SD | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 18.96 | 4.86 | |

| Age categories | ||||||||

| <31 (n = 44) | mean | 2.67 | 3.10 | 2.99 | 3.33 | 2.93 | 57.03 | 13.43 |

| SD | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 18.15 | 4.78 | |

| 31–40 (n = 63) | mean | 2.93 | 3.23 | 3.23 | 3.23 | 3.22 | 59.71 | 14.75 |

| SD | 0.86 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 17.83 | 4.45 | |

| 41–50 (n = 89) | mean | 3.00 | 3.32 | 3.29 | 3.39 | 3.24 | 61.63 | 13.87 |

| SD | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 20.04 | 5.20 | |

| 51–60 (n = 166) | mean | 3.21 | 3.43 | 3.36 | 3.56 | 3.37 | 65.51 | 15.57 |

| SD | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.76 | 18.51 | 4.70 | |

| >60 (n = 112) | mean | 3.15 | 3.39 | 3.31 | 3.51 | 3.35 | 68.03 | 15.42 |

| SD | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.71 | 18.56 | 4.87 | |

| F value | 6.36 | 4.72 | 3.73 | 4.37 | 3.15 | 4.28 | 3.21 | |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.002 | 0.013 | |

| Eta2 value | 0.051 | 0.039 | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.026 | 0.035 | 0.027 | |

| Gender * | ||||||||

| women (n = 353) | mean | 3.16 | 3.43 | 3.35 | 3.56 | 3.36 | 65.81 | 14.73 |

| SD | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 18.27 | 4.89 | |

| men (n = 120) | mean | 2.82 | 3.15 | 3.15 | 3.17 | 3.10 | 58.22 | 15.58 |

| SD | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 19.46 | 4.63 | |

| F value | 21.00 | 27.26 | 9.89 | 43.33 | 10.01 | 14.97 | 2.79 | |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.095 | |

| Eta2 value | 0.043 | 0.055 | 0.021 | 0.084 | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.006 | |

| Nature Relatedness (NR6) | Experience of Nature (ENS) | ENS—Everyday Detachment/Relaxation | ENS—Fascination with Nature/Wondering | ENS—Sense of Responsibility for Nature | Awe/Gratitude (GrAw-7) | Wellbeing (WHO-5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature-related variables | |||||||

| Nature Relatedness (NR6) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Experience of Nature Scale (ENS) | 0.695 ** | 1.000 | |||||

| ENS—Everyday detachment/Relaxation | 0.576 ** | 0.888 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| ENS—Fascination with nature/Wondering | 0.627 ** | 0.840 ** | 0.621 ** | 1.000 | |||

| ENS—Sense of responsibility for nature | 0.523 ** | 0.684 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.489 ** | 1.000 | ||

| Enjoying being outdoors (NR1) | 0.398 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.129 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.174 ** |

| Access to green spaces (minutes) | −0.157 ** | −0.075 | −0.033 | −0.084 | −0.080 | −0.085 | −0.015 |

| Wellbeing indicators | |||||||

| Awe/Gratitude (GrAw-7) | 0.555 ** | 0.545 ** | 0.437 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.375 ** | 1.000 | |

| Wellbeing (WHO5) | 0.164 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.178 ** | 0.186 ** | 0.077 | 0.416 ** | 1.000 |

| Dispositional gratitude (GQ-6) | 0.227 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.087 | 0.222 ** | 0.132 ** | 0.390 ** | 0.319 ** |

| Activities | |||||||

| Cycling outside | 0.088 | 0.094 | 0.049 | 0.059 | 0.167 ** | 0.034 | 0.111 |

| Sporting outside | 0.155 ** | 0.187 ** | 0.205 ** | 0.143 ** | 0.094 | 0.141 ** | 0.230 ** |

| Hiking/strolling outside | 0.326 ** | 0.242 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.242 ** | 0.118 | 0.301 ** | 0.168 ** |

| Meditation (incl. yoga) | 0.395 ** | 0.319 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.178 ** | 0.308 ** | 0.156 ** |

| Praying | 0.209 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.156 ** | 0.174 ** | 0.156 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.160 ** |

| Dependent Variable: Wellbeing (WHO-5) Inclusion Model: F = 15.5, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.254 | Beta | T | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | 2.246 | 0.025 | |

| Awe/Gratitude (GrAw-7) | 0.355 | 6.238 | <0.001 |

| Gratitude disposition (GQ-6) | 0.231 | 5.194 | <0.001 |

| Nature relatedness (NR-6) | −0.081 | −1.254 | 0.210 |

| Everyday detachment/Relaxation (ENS) | 0.037 | 0.680 | 0.497 |

| Fascination with nature/Wondering (ENS) | −0.077 | −1.249 | 0.212 |

| Sense of responsibility for nature (ENS) | −0.040 | −0.794 | 0.428 |

| Sporting outside | 0.168 | 3.942 | <0.001 |

| Hiking/strolling outside | 0.043 | 0.964 | 0.335 |

| Meditation (incl. yoga) | −0.009 | −0.201 | 0.841 |

| Praying | 0.036 | 0.818 | 0.414 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Büssing, A.; Wilhelm, J.; Rodrigues Recchia, D. Wondering Awe Is the Mediator of the Link Between Experience of Nature and Psychological Wellbeing—Relevance for Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111679

Büssing A, Wilhelm J, Rodrigues Recchia D. Wondering Awe Is the Mediator of the Link Between Experience of Nature and Psychological Wellbeing—Relevance for Public Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111679

Chicago/Turabian StyleBüssing, Arndt, Julia Wilhelm, and Daniela Rodrigues Recchia. 2025. "Wondering Awe Is the Mediator of the Link Between Experience of Nature and Psychological Wellbeing—Relevance for Public Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111679

APA StyleBüssing, A., Wilhelm, J., & Rodrigues Recchia, D. (2025). Wondering Awe Is the Mediator of the Link Between Experience of Nature and Psychological Wellbeing—Relevance for Public Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111679