Abstract

Residing in public housing is associated with adverse health outcomes, partly due to higher prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors linked to lower socioeconomic status. Health promotion and disease prevention interventions can mitigate these disparities but are often underutilized due to accessibility barriers and low health literacy. Delivering interventions directly within public housing areas may enhance reach and effectiveness. However, synthesized knowledge of such interventions remains limited. This scoping review aimed to identify and summarize available evidence on health-promoting and disease-preventive interventions in these settings. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRIMA-ScR) guidelines. A systematic search was performed in PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and Scopus. Articles were screened using predefined criteria. Intervention details, key findings, and digital components were extracted and categorized. 31 articles were included, covering eight intervention categories: (1) Health promoter programs, (2) Nutrition programs, (3) Health screenings, (4) Health promotion messages, (5) Physical activity programs, (6) Mental health programs, (7) Oral health programs, and (8) Other health interventions. Five articles incorporated digital components. This review highlights the value of resident involvement, demonstrated by positive outcomes in interventions with strong community engagement. Despite promising effects, digital health components were underutilized, representing a missed opportunity for scalable, cost-effective interventions.

1. Introduction

Residing in a public housing area is associated with adverse health outcomes [1]. The concept of public housing varies internationally and encompasses different governance models. In many contexts, public housing is not only provided directly by government authorities but also by non-profit housing organizations that operate to deliver affordable housing to low-income populations [2,3,4]. Non-profit-administered housing is often characterized by long-term tenancy, relatively stable resident populations, and a focus on community-oriented management [2,4]. Given these features, and to ensure a more consistent contextual basis, the present review defined public housing as affordable housing accessible to all individuals, primarily administered by non-profit organizations [3]. Public housing is primarily inhabited by individuals with lower socioeconomic status (SES), who often experience significantly adverse health outcomes compared to those with higher SES [5]. This health disparity is evidenced by an increased prevalence of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, adverse mental health, obesity, and elevated mortality rates [6,7,8]. These disparities can be explained by the fact that individuals with a lower SES often exhibit a higher prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, including smoking, physical inactivity, and poor dietary patterns [1,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Hence, addressing these health disparities requires targeted interventions regarding lifestyle behavior that consider the challenges faced by public housing residents.

Health promotion and disease prevention constitute essential intervention strategies for addressing these issues. Such interventions can reduce the risk of developing new health conditions, prevent the worsening of existing chronic diseases, and enhance individuals’ self-efficacy in managing their own health [15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, the utilization of such promotive and preventive healthcare interventions by residents in public housing areas is often hindered by multiple accessibility barriers. These barriers include significant geographical distances to healthcare services, which are typically located in health centers or similar facilities far from public housing areas [21,22]. In addition, the surrounding environment may lack walkability and perceived safety, making it difficult or unsafe for residents to engage in physical activity or to travel to these services on foot [21,22,23]. Limited public transportation options and time-consuming travel further restrict access [21,22]. Moreover, residents in public housing areas frequently experience limited health literacy, which may affect their understanding of both the importance and the content of health promotion and disease prevention initiatives [24,25]. This limited health literacy can lead to a lack of awareness and comprehension of available healthcare services and how to utilize them effectively [21,24,26]. Consequently, bringing health promotion and disease prevention initiatives closer to public housing areas may enhance accessibility and safety, and ensure that the interventions are more effective and widely utilized.

Despite the importance of health promotion and disease prevention interventions in public housing areas, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding the specific strategies that have been implemented in these settings. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no literature review has been conducted to gather and synthesize the experiences from such interventions. Therefore, this scoping review seeks to identify and map the available evidence on health promotion and disease prevention interventions in public housing areas. It aims to address the research question: What health-promoting and disease-preventive interventions are identified in public housing areas? Additionally, digital components applied in the interventions will be identified and mapped, as digitalization has had a major impact in health promotion and preventive interventions, demonstrating great potential for increasing health outcomes and ensuring proximity of the interventions [27,28,29,30,31]. However, factors such as poverty, limited digital access and low literacy in public housing areas may affect the feasibility of these components, which makes it important not only to identify them but also to assess their effect [32].

2. Materials and Methods

The current scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [33] (Supplementary Material S1). This scoping review was conducted without a preregistered protocol.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Original peer-reviewed articles that described completed health-promoting and disease-preventive interventions in public housing areas were included. Public housing was understood as non-profit administered, affordable housing, and studies conducted in temporary or exclusively government-owned housing models were excluded. The results of the interventions needed to be presented in the articles to be included. Full-text articles published between 1 January 2004 and 18 September 2024 were considered for inclusion. Articles written in English or any of the Scandinavian languages were accepted. Articles describing interventions in public housing areas exclusively government owned or reserved for specific social groups were excluded to ensure homogeneous contexts. Additionally, articles describing interventions focusing on environment or interior in relation to health promotion were excluded as the review focused solely on interventions targeting the individual. If an article reported on multiple interventions, it was included only if the results for environmental and individual-based interventions were presented separately.

2.2. Search Strategy

Initially, a non-systematic search was performed in PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar to identify relevant search terms, keywords, and index terms to incorporate in the systematic search. Following this, the systematic literature search was performed in four relevant databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and Scopus on the 18th of September 2024. The search strategy involved a block search comprising two main blocks, using the overall search terms “Public Housing” and “Health-promoting or preventive interventions,” respectively. To broaden the search, we incorporated synonyms for the primary search term, utilizing a combination of MeSH terms and relevant keywords. An experienced research librarian was consulted to validate the search strategy. One review author (SLJ) performed the searches in the databases. For full-electronic search strategy, see Supplementary Material S2.

2.3. The Screening Process

First, all articles identified through the systematic search were collected and uploaded into RefWorks 2024, where duplicates were removed. Second, all remaining articles were screened by title and abstract by one review author (SLJ) to assess their eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. In case of uncertainty regarding the relevance of an article, another review author (IEG) was consulted. Third, the remaining articles were assessed for full-text screening (SLJ, IEG). During the full-text screening, reasons for exclusion of articles were registered and presented in a PRISMA flow diagram. Any disagreement between the review authors during the screening process was resolved through discussion or by involving a third author (SH).

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

All articles included following full-text screening were read profoundly by one review author (IEG). The table function in Microsoft Word 2024 was utilized to extract data from each included article, following a predefined table format that was agreed upon by three of the review authors (SLJ, IEG, SH). The following article details were extracted: Author, year, population, type of housing, aim of intervention, description of the intervention, digital component (if any), and key findings. In case of uncertainty regarding article details, another review author (SLJ) was consulted. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion or by involving a third reviewer (SH).

Extracted details from the articles were utilized to synthesize categories based on the type of health-promoting or disease-preventive intervention by review author IEG. An article could be included under multiple categories if the intervention contained various aspects relevant to different categories. Separate tables based on the identified categories were created, and the content of each category was summarized. One review author, SH, validated the synthesis of categories. Furthermore, a separate table was created to summarize the articles in which a digital component was identified. This table provided descriptions of the digital elements involved in the interventions.

2.5. Ethics Approval

As the review used publicly available data from previously published studies, ethical approval was not required.

3. Results

3.1. Screening and Search Outcomes

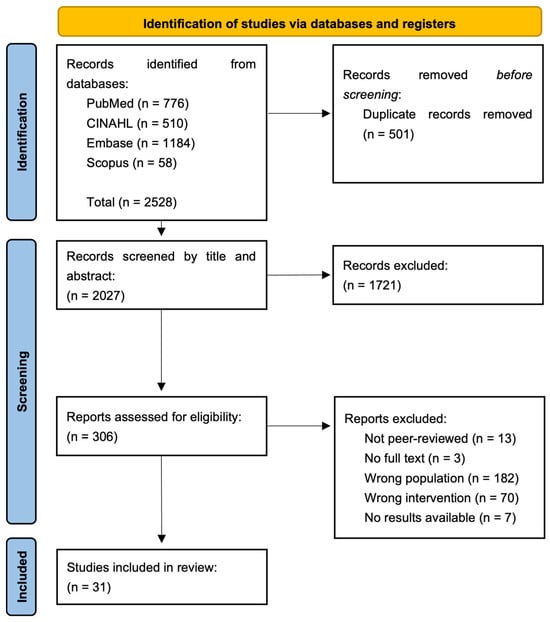

A total of 2528 articles were identified in the systematic search, of which 501 were duplicates. After removing the duplicates, the remaining 2027 articles underwent screening on title and abstract, where 1721 articles were excluded due to irrelevance. Subsequently, 306 articles underwent full-text screening, where 275 articles were excluded, mainly because they focused on a wrong population (n = 182) or did not contain a health promotion or disease-preventive intervention (n = 70). After full-text screening, 31 articles were included in the current review. Figure 1 illustrates the full screening process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included articles are presented in Supplementary Material S3. The included articles were published between 2004 and 2024, of which the majority (n = 25) were carried out in USA (80.6%), two in Denmark (6.5%), two in Canada (6.5%), one in China (3.2%), and one in Australia (3.2%). Five articles (16.1%) included a digital intervention component. A mixed-methods approach was applied in eight (26%) of the included articles. Seven articles (23%) employed a pre-post-test design, and seven (23%) used a qualitative design. A cluster randomized trial design was applied in four articles (13%), while three (10%) articles used a feasibility study design. The remaining two articles employed a non-randomized pilot study design (3%) and a randomized controlled trial design (3%), respectively.

3.3. Synthesized Findings

The interventions described in the included 31 articles revealed eight different categories including: (1) Health promoter programs, (2) Nutrition programs, (3) Health screenings, (4) Health promotion messages, (5) Physical activity programs, (6) Mental health programs, (7) Oral health programs, and (8) Other health interventions. Eight articles were included in more than one category.

3.3.1. Health Promoter Programs

Health promoter programs (Table 1) included training residents to become community health advocates. In many cases, residents applied to participate in the health promoter programs [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], and they often reflected the broader resident population by having the same linguistic and cultural background [36,37,38,40]. The training content commonly included, leadership skills, needs assessments, health promotion activities (e.g., exercise, nutrition, mental health, health screenings, smoking cessation, and navigating healthcare services), self-management theories, and chronic disease education such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Following training, four studies reported that health advocates conducted needs assessments among residents and implemented health promotion activities based on identified priorities [34,35,37,41]. The health advocates were generally responsible for organizing activities, recruiting participants, and facilitating implementation [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. The duration of training ranged from 30 to 56 h, and the subsequent community-based activities lasted from four weeks to two years. Several studies reported that the involvement of community health advocates contributed to increased community engagement, enhanced understanding of health promotion and disease prevention, improved trust, and better access to health services [34,35,36,37,39,41]. Community activities were often successfully implemented due to the engagement and leadership of the community health advocates [34,35,36,37,41]. Only one study reported challenges, primarily related to insufficient training and unclear role definitions for the health advocates [42]. Five of the nine studies reported positive health-related changes, such as reduction in blood glucose, blood pressure and weight, improvements in oral hygiene, and increases mental health [36,38,39,40,41].

Table 1.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Health promoter programs”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, training duration, and key findings are stated.

3.3.2. Nutrition Programs

Nutrition programs (Table 2) included nutrition education, food-related skill development, interactive gardening, hands-on gardening and cooking, cooking demonstrations, easy access to fruits and vegetables, participatory theater show about making healthy choices, motivational interviewing counseling, cookbooks with healthy recipes, health promotion messages, weight management strategies, and strategies for eating healthy on a budget [35,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. The frequency of the interventions varied from once a week to twice a week and lasted up to one year. One study included a “booster” session at the end of the program [49]. Several studies reported an increase in the average servings of fruits and vegetables [35,44,45,48], while only one study found no change [49]. Three studies reported an overall decrease in average total caloric intake, consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and foods, and frequency of fast-food consumption [35,47,49]. Across many studies, participants experienced increased knowledge of gardening and healthy eating and willingness to try fruits and vegetables [44,46,47,52]. One study reported that the program improved social connections and reduced exposure to gangs and drugs [50].

Table 2.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Nutrition programs”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, frequency, duration, and key findings are stated.

3.3.3. Health Screenings

Health screenings (Table 3) contained life-style questionnaires, screening for psychosocial service needs, and physical examinations measuring, for example, blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin A1c, weight, height, waist circumference, and fitness level [35,40,43,53,54,55]. The screenings were offered to identify health risks such as diabetes [35,40,43,53,54,55]. The screening results were often shared with the participants through a dialogue with the health screener [35,40,43,53,55]. Those at risk were advised to consult a general practitioner or referred to relevant health programs [35,53,55]. Health screenings were primarily held at community centers [35,40,43,53,54] and offered approximately once or twice a week for a maximum of one year. In two studies, residents perceived the health screenings as valuable [53,55], whereas one study noted a lack of meaningful support and follow-up from healthcare professionals [55]. Several studies found decreases in BMI, healthier life-style behaviors, and improvements in mental well-being [35,40,43,53]. One study reported that high attendance at the screenings was linked to active community leaders [54].

Table 3.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Health screenings”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, who conducted it, and key findings are stated.

3.3.4. Health Promotion Messages

Health promotion messages (Table 4) focused on HPV vaccination, cervical cancer screening, and sugar-sweetened beverages and foods [51,56]. The messages had an educational purpose targeting self-efficacy and motivation, and included photos, web-links, advice, and factual information [51,56]. One study delivered the messages through Twitter [56], while the other used SMS and other social media platforms [51]. The messages were delivered once a day or every other day for one month. Most participants perceived the health promotion messages as a suitable educational strategy [51,56], but no significant impact on the participants’ health behaviors or intentions were reported [56]. One study reported that messages targeting motivation were rated lowest in terms of satisfaction [51].

Table 4.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Health promotion messages”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, frequency, duration and key findings are stated.

3.3.5. Physical Activity Programs

Physical activity programs (Table 5) included walking groups, women-only exercise activities, gentle exercise programs, workshop sessions focusing on exercise and its benefits, and physical activities delivered through fun and entertaining formats [35,47,48,50,52,53,57,58]. One program used prizes and acknowledgements to motivate the participants [57]. The frequency of the interventions varied from five times a week to one session per month. Some studies reported high participant satisfaction with the physical activities and workshop content [47,50,52,53]. Programs that included walking groups were associated with significant increases in minutes walked per day and enhanced social connections among neighbors [35,57]. Additionally, two studies focusing on adolescent girls found increases in physical activity levels [48,59]. One study reported that women-only exercise had high attendance, and participants appreciated the opportunity to join activities where they felt safe, which provided personal time and social opportunities [58].

Table 5.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Physical activity program”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, frequency, duration, and key findings are stated.

3.3.6. Mental Health Programs

Mental health programs (Table 6) were delivered through group sessions or open workshops that focused on specific themes such as aging, depression, social isolation, men’s health, social support, and health topics like diabetes [53,60]. The frequency of sessions ranged from weekly to once every six to eight weeks. Participants in these studies generally perceived the programs as effective, reporting improved social interactions, and increased mental well-being [53,60].

Table 6.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Mental health programs”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, duration and key findings are stated.

3.3.7. Oral Health Programs

Oral health programs (Table 7) included motivational interviewing, which were used to analyze the participants situation and develop plans for oral hygiene, combined with practical training in tooth brushing and flossing techniques [61,62]. Moreover, one program also included health fairs with practical oral hygiene activities, question sessions, and campaign messages on oral hygiene to reinforce the motivational interviewing [61]. The interventions lasted six months. Participants in both studies demonstrated significant improvements in oral hygiene (plaque scores, Gingival index, and brushing/flossing skills) and improvements in Oral Health-related Quality of Life [61,62].

Table 7.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Oral health programs”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, duration and key findings are stated.

3.3.8. Other Health Interventions

The category other health interventions (Table 8) included a smoking cessation program [40], a sexual health program [63], and a social-enhancing activity [64].

Table 8.

Overview of the articles included in the category “Other health interventions”. The authors, year of publication, content of the intervention, duration, and key findings are stated.

The smoking cessation program included a weekly supply of nicotine replacement therapy and personal behavioral counseling [40]. It was held in the local community center. The intervention lasted four weeks. About 30.7% of the participants achieved cessation, but no significant change in exhaled carbon monoxide levels among the participants was reported [40].

The sexual health program included educational workshops supplemented with written material focusing on sexually transmitted infections, safe sex behaviors and symptoms, combined with few practical demonstrations and role-playing scenarios [63]. It was held at the community centres and lasted 30 to 45 min each time. Participants were satisfied with the sexual health program and expressed and demonstrated new skills and increased confidence [63].

Social-enhancing activities such as bus trips, guided tours, and lunch were organized for residents [64]. These activities were held two times over a four-month period. Participants expressed enhanced social interaction, which fostered a sense of community [64]. However, linguistic and cultural differences posed a significant challenge [64].

3.3.9. Digital Components

Five of the included articles utilized digital components as part of their interventions (Table 9). Velez et al. and Allen et al. provided health promotion information and advice via SMS or social media, while Schwinn et al. delivered an internet-based health promotion program [48,51,56]. Deville-Stoetzel et al. used automatically generated reminder messages to inform residents about health promotion workshops, whereas Ahluwalia et al. conducted motivational interviews with included residents over the phone and used educational videos about fruits and vegetables [44,54]. None of articles reported results directly related to the effect of using a digital component.

Table 9.

Overview of the articles utilizing a digital component as a part of their intervention. The authors, year of publication, and description of the digital component is stated.

4. Discussion

The current scoping review aimed to identify and map the available evidence regarding health-promoting and disease-preventive interventions in public housing areas. The interventions were categorized into eight themes, with the most covered theme being nutrition education (36%), followed by health promoter program (30%) and physical activities (26%).

Nine of the included articles involved training residents to become health promoters in their own public housing area [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. This involvement of residents in developing and implementing health promotion and disease-preventive interventions could be crucial for their success. A review by Cyril et al. explored the level of community engagement and health outcomes in health promotion interventions in urban areas. They found that a high level of community engagement was associated with positive health outcomes compared to interventions with low community engagement [65]. This finding is supported by several reviews, which found health promoters to be effective in health promotion in different settings [66,67,68]. The findings suggest that empowering residents to take an active role in health promotion within their communities can lead to more effective and sustainable interventions. Additionally, training residents as health promoters could be a cost-effective way to extend the reach of health interventions, particularly in resource-limited settings [69].

Only five (16%) of the included studies incorporated a digital component, and none of them reported outcomes directly related to the digital element. Although studies in other settings have shown promising effects on health outcomes related to health promotion and disease prevention when digital components are included [27,28,29,30,31], their use within public housing remains limited and insufficiently evaluated, indicating a need for greater scientific focus within this area. Digital health interventions may offer flexibility and potential to tailor content to residents’ needs and circumstances [70], which could be beneficial in public housing areas, where health needs and access to resources vary [5,21]. However, their implementation may be challenged by factors such as limited access to devices and low digital literacy [21,26]. Therefore, applicability of digital components in this context should be approached with caution, and future research is needed to determine under which conditions, and for whom, digital interventions can be both feasible and effective.

A significant number of studies within this scoping review reported the effects of their interventions through narrative or qualitative syntheses rather than quantifiable measures. While this may limit the ability to directly compare outcomes across studies [71], narrative syntheses and qualitative approaches are valuable within health promotion research because they can capture nuance and contextual complexity that quantitative measures may overlook [72,73]. However, the diversity in reporting formats and methodological approaches poses challenges for consistency, reproducibility, and generalizability of findings [71]. This suggests that the current evidence base may not yet be fully mature and highlights the need for methodological approaches that better integrate both qualitative and quantitative data to enable more comprehensive and comparable assessments of intervention effects.

The current scoping review has several limitations. One significant limitation is the variability in the definition of public housing across different countries. Public housing, also referred to as social housing, is subject to diverse interpretations and implementations depending on national policies, economic conditions, and cultural contexts. To minimize variability, public housing was defined as affordable housing accessible to all individuals and not exclusively government-owned. However, as this is a scoping review, the emphasis on homogeneity may have inadvertently constrained the breadth of the evidence base, thereby challenging the exploratory nature of the scoping methodology [74]. Thus, our findings may not be fully transferable to settings with different governance structures, such as entirely government-owned housing (e.g., the USA, England, and Canada) [75,76]. Future research should compare interventions across different public housing models to capture the full diversity of contexts in which health promotion interventions are implemented. Another limitation is that this review focused only on individually oriented interventions. This has excluded environmental or policy-level strategies, which are known to be highly effective in health promotion [77,78]. Future research should therefore examine multiple levels of intervention to capture the full scope of health promotion efforts in public housing contexts.

5. Conclusions

The current scoping review identified a range of health-promoting and disease prevention interventions in public housing areas, with nutrition education, health promoter programs, and physical activity being the most common. Notably, resident involvement through training as health promoters emerged as a key strategy, supporting evidence that community engagement enhances intervention effectiveness and sustainability. These findings highlight the importance of empowering residents to take active roles in shaping health initiatives within their communities. Despite the growing relevance of digital health, digital components were rarely incorporated and insufficiently evaluated, indicating a need for cautious consideration and further research to determine their feasibility in contexts characterized by limited access and digital literacy. Qualitative and narrative approaches offer valuable contextual insight, but the diversity of methods and reporting formats limits consistency and comparability across studies. Future research should examine different models of public housing and apply multi-level strategies—combining individual, environmental, policy-level, and potentially digital approaches—to strengthen the evidence base and support scalable health promotion interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22111624/s1, Supplementary Material S1: PRISMA-ScR Checklist; Supplementary Material S2: Overview of the full database searches; Supplementary Material S3: Characteristics of included articles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E.G., S.L.J., V.B.L. and S.H.; methodology, I.E.G. and S.L.J.; validation, V.B.L. and S.H.; formal analysis, I.E.G. and S.L.J.; investigation, I.E.G. and S.L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, I.E.G.; writing—review and editing, I.E.G., S.L.J., V.B.L. and S.H.; supervision, S.H.; project administration, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank research librarian Connie Skrubbeltrang for her assistance with and refinement of the literature search.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| SMS | Short Message Service |

| HPV | Humant Papillomavirus |

References

- Pickett, K.E. Multilevel Analyses of Neighbourhood Socioeconomic Context and Health Outcomes: A Critical Review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2001, 55, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, C.M.E. (Ed.) Social Housing in Europe; School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-85328-100-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R.; Haagerup, C. The Danish Social Housing Sector: Recent Changes and Future Challenges. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2017, 4, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Housing Europe Observatory. The State of Social Housing in Europe 2023. Available online: https://www.housingeurope.eu/the-state-of-the-housing-in-europe-2023/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Barakat, C.; Konstantinidis, T. A Review of the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status Change and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Batty, G.D.; Pentti, J.; Shipley, M.J.; Sipilä, P.N.; Nyberg, S.T.; Suominen, S.B.; Oksanen, T.; Stenholm, S.; Virtanen, M.; et al. Association between Socioeconomic Status and the Development of Mental and Physical Health Conditions in Adulthood: A Multi-Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e140–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agardh, E.; Allebeck, P.; Hallqvist, J.; Moradi, T.; Sidorchuk, A. Type 2 Diabetes Incidence and Socio-Economic Position: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringhini, S.; Carmeli, C.; Jokela, M.; Avendaño, M.; Muennig, P.; Guida, F.; Ricceri, F.; d’Errico, A.; Barros, H.; Bochud, M.; et al. Socioeconomic Status and the 25 × 25 Risk Factors as Determinants of Premature Mortality: A Multicohort Study and Meta-Analysis of 1·7 Million Men and Women. Lancet 2017, 389, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algren, M.H.; Bak, C.K.; Berg-Beckhoff, G.; Andersen, P.T. Health-Risk Behaviour in Deprived Neighbourhoods Compared with Non-Deprived Neighbourhoods: A Systematic Literature Review of Quantitative Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.H.; Habtewold, T.D.; Birhanu, M.M.; Sissay, T.A.; Tegegne, B.S.; Abuzerr, S.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Neighbourhood Socioeconomic Status and Overweight/Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A.V.; Mair, C. Neighborhoods and Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiscock, R.; Bauld, L.; Amos, A.; Fidler, J.A.; Munafò, M. Socioeconomic Status and Smoking: A Review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1248, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidlow, C.; Johnston, L.H.; Crone, D.; Ellis, N.; James, D. A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Socio-Economic Position and Physical Activity. Health Educ. J. 2006, 65, 338–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giskes, K.; Avendaňo, M.; Brug, J.; Kunst, A.E. A Systematic Review of Studies on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Dietary Intakes Associated with Weight Gain and Overweight/Obesity Conducted among European Adults. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, L. From Disease Prevention to Health Promotion. JAMA 1999, 281, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzerounian, J.; Pirrie, M.; AlShenaiber, L.; Angeles, R.; Marzanek, F.; Agarwal, G. Health Knowledge and Self-Efficacy to Make Health Behaviour Changes: A Survey of Older Adults Living in Ontario Social Housing. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, L.; Andersen, V.J.; Arnoldsen, J.; Maindal, H.T. Effectiveness of a Brief Theory-Based Health Promotion Intervention among Adults at High Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: One-Year Results from a Randomised Trial in a Community Setting. Prim. Care Diabetes 2016, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, P.; Morton, D.P.; Diehl, H.; Gobble, J.; Morey, P.; Chang, E. Effectiveness of a Volunteer-Delivered Lifestyle Modification Program for Reducing Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 109, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestwich, A.; Kellar, I.; Parker, R.; MacRae, S.; Learmonth, M.; Sykes, B.; Taylor, N.; Castle, H. How Can Self-Efficacy Be Increased? Meta-Analysis of Dietary Interventions. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D.; Muscat, D.M. Health Promotion Glossary 2021. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 1578–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, J.B.; Kaneda, T. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Access to Health Care. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryvicker, M. A Conceptual Framework for Examining Healthcare Access and Navigation: A Behavioral-Ecological Perspective. Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.K.; Kirtland, K.A.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Addy, C.L. Socioeconomic Status and Perceptions of Access and Safety for Physical Activity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 28, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stormacq, C.; Van Den Broucke, S.; Wosinski, J. Does Health Literacy Mediate the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Health Disparities? Integrative Review. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, e1–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, M.T.; Bak, C.K.; Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.; Riddersholm, S.J.; Skals, R.K.; Mortensen, R.N.; Maindal, H.T.; Bøggild, H.; Nielsen, G.; et al. Associations of Health Literacy with Socioeconomic Position, Health Risk Behavior, and Health Status: A Large National Population-Based Survey among Danish Adults. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.I.; Lee, S.-Y.D.; Arozullah, A.M.; Crittenden, K.S. Effects of Health Literacy on Health Status and Health Service Utilization amongst the Elderly. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1809–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deady, M.; Choi, I.; Calvo, R.A.; Glozier, N.; Christensen, H.; Harvey, S.B. eHealth Interventions for the Prevention of Depression and Anxiety in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, A.L.; Geukes, C.; Dockweiler, C. Digital Health Promotion and Prevention in Settings: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e21063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Shang, B.; Liang, W.; Du, G.; Yang, M.; Rhodes, R.E. Effects of eHealth-Based Multiple Health Behavior Change Interventions on Physical Activity, Healthy Diet, and Weight in People With Noncommunicable Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.J.; Lou, J.Q.; Ownby, R.L.; Caballero, J. A Systematic Review of eHealth Interventions to Improve Health Literacy. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muellmann, S.; Forberger, S.; Möllers, T.; Bröring, E.; Zeeb, H.; Pischke, C.R. Effectiveness of eHealth Interventions for the Promotion of Physical Activity in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Prev. Med. 2018, 108, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, J.; Motulsky, A.; Denis, J.-L. Digital Health Technologies and Inequalities: A Scoping Review of Potential Impacts and Policy Recommendations. Health Policy 2024, 146, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, D.J.; Bhosrekar, S.G.; Rorie, J.-A.; Goodman, R.; Thomas, G.; Maxwell, N.I.; Smith, E. Resident Health Advocates in Public Housing Family Developments. Fam. Community Health 2015, 38, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bowen, D.J.; Quintiliani, L.M.; Bhosrekar, S.G.; Goodman, R.; Smith, E. Changing the Housing Environment to Reduce Obesity in Public Housing Residents: A Cluster Randomized Trial. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Vaughn, N.A.; Lin, A.J.; Browne, R.; White, M.; Smith, P. Healthy Families Brooklyn: Working with Health Advocates to Develop a Health Promotion Program for Residents Living in New York City Housing Authority Developments. J. Community Health 2011, 36, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.L.; Li, T.; Kaplan, S.A.; Ellen, I.G.; Gourevitch, M.N.; Young, A.; Doran, K.M. Community Health Worker Intervention in Subsidized Housing: New York City, 2016-2017. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassaballa, I.; Ebekozien, O.; Ogungbadero, A.; Williams, F.; Schultz, J.; Hunter-Skidmore, J.; Fawcett, S.; Watson-Thompson, J. Evaluation of a Diabetes Care Coordination Program for African-American Women Living in Public Housing. J. Clin. Outcomes Manag. 2015, 22, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, A.Y.; Stewart, S.M.; Wan, A.; Fok, H.; Lai, H.Y.W.; Lam, T.-H.; Chan, S.S. Development and Evaluation of a Training Workshop for Lay Health Promoters to Implement a Community-Based Intervention Program in a Public Low Rent Housing Estate: The Learning Families Project in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, M.S.; Oliver-Keyser, T.; Galiatsatos, P.; Burdalski, C.; Addison, B.; Lewis-Land, C.; Butz, A. Alignment of Medical and Psychosocial Sectors for Promotion of Tobacco Cessation among Residents of Public Housing: A Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Young, S.; Beck, B.; Maurana, C.A.; Murphy, M.; Holifield, J.; Aitch, C. Leadership in a Public Housing Community. J. Health Commun. 2004, 9, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.; Ferdinand, A.; Hussein, A.; Hussein, R.; Kaufman, J.; Edler, P.; Allard, N.; Danchin, M.; Gibney, K.B. Evaluating a Peer-to-Peer Health Education Program in Australian Public Housing Communities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G.; Angeles, R.; Pirrie, M.; McLeod, B.; Marzanek, F.; Parascandalo, J.; Thabane, L. Reducing 9-1-1 Emergency Medical Service Calls By Implementing A Community Paramedicine Program For Vulnerable Older Adults In Public Housing In Canada: A Multi-Site Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2019, 23, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, J.S.; Nollen, N.; Kaur, H.; James, A.S.; Mayo, M.S.; Resnicow, K. Pathway to Health: Cluster-Randomized Trial to Increase Fruit and Vegetable Consumption among Smokers in Public Housing. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, E.W.; Bera, V.; Elsemore, J.; Snelling, A. Examining the Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Community-Based Obesity Prevention Program. Am. J. Health Educ. 2018, 49, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, K.; Hill, J.L.; Reese, F.; Covington, C.; Bennette, F.; MacAuley, L.; Zoellner, J. Feasibility of an Experiential Community Garden and Nutrition Programme for Youth Living in Public Housing. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2759–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuross, E.; Folta, S. Involving Cultural Institutions in the Prevention of Childhood Obesity: The Boston Children’s Museum’s GoKids Project. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinn, T.M.; Schinke, S.; Fang, L.; Kandasamy, S. A Web-Based, Health Promotion Program for Adolescent Girls and Their Mothers Who Reside in Public Housing. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shankar, S.; Klassen, A.C.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Houts, P.S.; Wang, T.; McCarthy, M.; Cain, R.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of a Nutrition Education Intervention for Women Residents of Washington, DC, Public Housing Communities. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 22, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strunin, L.; Wulach, L.; Yang, G.J.; Evans, T.C.; Hamdan, S.U.; Davis, G.L.; Bowen, D.J. Preventing Cancer: A Community-Based Program for Youths in Public Housing. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, S83–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez, M.; Quintiliani, L.M.; Fuertes, Y.; Román, A.; Heaton, B. Photo-Enhanced Health Promotion Messages to Target Reduction in Dietary Sugar among Residents of Public Housing. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Rosenberg, A.; Gilmore, L.; Withey, M.; Breault, A. Implementation of a Diabetes Prevention Program in Public Housing Communities. Public Health Nurs. 2014, 31, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aselton, P. Using a Wellness Program in Public Housing for Community Nursing Clinical Experiences. J. Nurs. Educ. 2011, 50, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deville-Stoetzel, N.; Kaczorowski, J.; Agarwal, G.; Lussier, M.-T.; Girard, M. Participation in the Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) by Older Adults Residing in Social Housing in Quebec: Social Network Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, A.; Merrild, C.H. Exploring Targeted Preventive Health Checks in a Socially Disadvantaged Neighborhood in Denmark. Health. Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.D.; Hollander, J.; Gualtieri, L.; Alarcon Falconi, T.M.; Savir, S.; Agénor, M. Feasibility of a Twitter Campaign to Promote HPV Vaccine Uptake among Racially/Ethnically Diverse Young Adult Women Living in Public Housing. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J.; Rabkin, J.; Sharify, D.; Song, L. High Point Walking for Health: Creating Built and Social Environments That Support Walking in a Public Housing Community. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, L.G.; Sharify, D.; Krieger, J.; Saelens, B.E.; Calleja, J.; Aden, A. Be Active Together: Supporting Physical Activity in Public Housing Communities through Women-Only Programs. Prog. Community Health. Partnersh. 2013, 7, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunin, L.; Douyon, M.; Chavez, M.; Bunte, D.; Horsburgh, C.R. The GirlStars Program: Challenges to Recruitment and Retention in a Physical Activity and Health Education Program for Adolescent Girls Living in Public Housing. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A42. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson, L.D.; Dorsey, C.; Berg, J.; Rose, L.E. Enhancing Self-Care in Community Dwelling Older Adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2004, 25, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisine, S.; Schensul, J.J.; Goldblatt, R.; Radda, K.; Foster-Bey, C.; Acosta-Glynn, C.; Miron-Carcamo, L.; Ioannidou, E. A Bi-Level Intervention to Improve Oral Hygiene of Older and Disabled Adults in Low-Income Housing: Results of a Pilot Study. Community Dent. Health 2016, 33, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Reisine, S.; Schensul, J.J.; Salvi, A.; Grady, J.; Ha, T.; Li, J. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes in a Randomized Clinical Trial to Assess a Community-Based Oral Hygiene Intervention among Adults Living in Low-Income Senior Housing. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedin, T.C.; Resnick, B. Increasing Risk Awareness and Facilitating Safe Sexual Activity among Older Adults in Senior Housing. J. Community Health Nurs. 2014, 31, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivarathan, A.; Lund, R.; Christensen, U.; Kristiansen, M. Social Relations, Community Engagement and Potentials: A Qualitative Study Exploring Resident Engagement in a Community-Based Health Promotion Intervention in a Deprived Social Housing Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyril, S.; Smith, B.J.; Possamai-Inesedy, A.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Exploring the Role of Community Engagement in Improving the Health of Disadvantaged Populations: A Systematic Review. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 29842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeet, G.; Thakur, J.S.; Prinja, S.; Singh, M. Community Health Workers for Non-Communicable Diseases Prevention and Control in Developing Countries: Evidence and Implications. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, S.L.; Chowdhury, F.M.; Van Le, K.; Horsley, T.; Brownstein, J.N.; Zhang, X.; Jack, L.; Satterfield, D.W. Effectiveness of Community Health Workers in the Care of Persons with Diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2006, 23, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider, S.M. Outcome Effectiveness of Community Health Workers: An Integrative Literature Review. Public Health Nurs. 2002, 19, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, K.; Kok, M.C.; Witter, S.; Dieleman, M. Costs and Cost-Effectiveness of Community Health Workers: Evidence from a Literature Review. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erku, D.; Khatri, R.; Endalamaw, A.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. Digital Health Interventions to Improve Access to and Quality of Primary Health Care Services: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, K. Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Traditions: Epistemological, Theoretical, and Methodological Differences. Euro J. Educ. 2013, 48, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, A.; Schneider, R.; DeNomie, M.; Kusch, J.; Welch, W.; Sosa, M.; Yeldell, S.; Maida, T.; Wineberg, J.; Holt, K.; et al. Assessing Health Promotion Interventions: Limitations of Traditional Research Methods in Community-Based Studies. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 19, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, J.; Robertson, A.; Poland, B.; Coburn, D.; Edwards, R. Towards a Critical Social Science Perspective on Health Promotion Research. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.M.; Andrews, R. The Politics of Public Housing Reform: Local Government Stock Transfer in England. Int. Public Manag. J. 2018, 21, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davlasheridze, M.; Miao, Q. Natural Disasters, Public Housing, and the Role of Disaster Aid. J. Reg. Sci. 2021, 61, 1113–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Marple, K.; Marinello, S.; Moore, T.E.; Powell, L.M. Outcomes Following Taxation of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2215276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Hosking, J.; Woodward, A.; Witten, K.; MacMillan, A.; Field, A.; Baas, P.; Mackie, H. Systematic Literature Review of Built Environment Effects on Physical Activity and Active Transport—An Update and New Findings on Health Equity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).