Empowering Vulnerable Communities Through HIV Self-Testing: Post-COVID-19 Strategies for Health Promotion in Sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

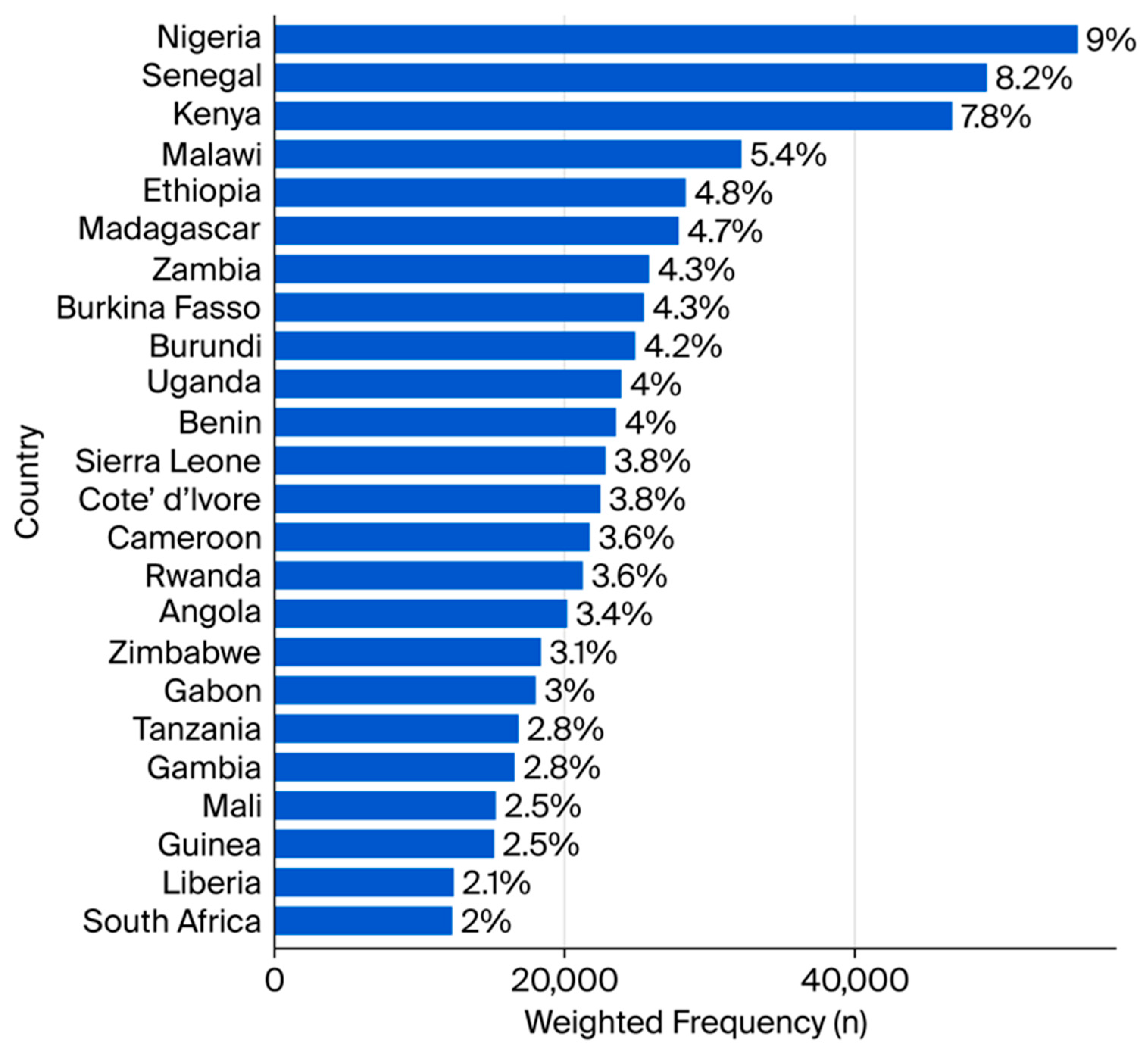

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Participants and Measurement

2.4. Validity

2.5. Reliability

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Sociodemographic and Economic Characteristics

3.1.2. Knowledge, Behavioural and Psychosocial Factors, Attitude, and Uptake of HIV Self-Testing

3.1.3. Determinants of HIV Self-Testing Uptake

Sociodemographic and Economic Factors

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2.2. Theme 1: Empowerment Through HIVST

“I would like to use it on my own because it’s for my privacy. I don’t want anyone to know my business or to interfere in personal matters that I prefer to keep confidential. With self-testing, I can manage my health privately without the fear of people gossiping, judging me, or making assumptions about my lifestyle.”(FSW-03)

“It is important to me because it’s my privacy. People are not supposed to know about my HIV status or even that I am getting tested, and it should remain confidential at all times. If people in my community find out, they might start treating me differently, gossip about me, or even discriminate against me openly.”(FSW-09)

“This kit makes me my own doctor. I can know my status without telling anybody. It gives me the power to decide when and if I want to share my result with someone else.”(FSW-13)

“It saves me the stress of going to the hospital. I don’t have to wait in a long line or deal with the crowds at the clinic, which can be very tiring and frustrating.”(FSW-04)

“I felt privileged that I could use it because not everyone has the opportunity or access to test themselves privately. Having the option to test at home, without needing to go through the hospital system, made me feel empowered and independent.”(FSW-13)

“It’s fast, and you receive your result immediately, which makes a big difference compared to going to a hospital. You don’t have to wait for hours, book an appointment, or come back days later to collect your results.”(FSW-01)

3.2.3. Theme 2: Barriers and Vulnerabilities Post-COVID-19

Financial Barriers and Affordability Concerns

“Yes, they need to make it very affordable for everybody, like N200 naira (less than $1 USD). Many people living in brothels or low-income areas do not have enough money to spend on health services, especially for something like HIV self-testing, which they may not see as an immediate priority.”(FSW-01)

“For me, the availability of the kit and affordability should be prioritized. Many people are afraid or reluctant to visit hospitals for HIV testing because of the stigma they might face or the time and cost involved.”(FSW-02)

“Even if it’s available, how many people can afford it? Some people are struggling to feed, talk less of buying a test kit. Government needs to help make it cheaper.”(FSW-06)

Fear, Anxiety, and Emotional Distress

“I wouldn’t want to do it alone because I am afraid of needles and the whole process makes me very anxious. If I were to get a bad result while I’m alone, I wouldn’t know what to do or how to handle the emotional shock.”(FSW-11)

“It’s scary because you are by yourself. If the result is bad, you might panic and do something dangerous. At least in the hospital, there are people to help you.”(FSW-07)

“I think people might make mistakes or misinterpret the results, especially if they are nervous or scared. Some people can go into shock if they see a positive result and they are alone.”(FSW-12)

Perceived Stigma and Confidentiality Risks

“If people find out, they will discriminate against you, even if you are just trying to take care of your health. In our communities, once someone hears you are testing for HIV, they may start spreading rumors or treating you differently.”(FSW-09)

“If someone sees me with the kit, they will think I have HIV already. They will avoid me or gossip about me.”(FSW-10)

“I’m afraid that if my partner finds it, he will accuse me of hiding something and maybe even beat me. That’s why I prefer not to keep it in the house.”(FSW-08)

3.2.4. Theme 3: Community-Driven Strategies for Health Promotion

Peer-to-Peer Support and Education

“Peer-to-peer conversations are important because we can easily detect one who might be infected by noticing certain complaints like constant headaches or sweating. The strategy is to bring the person closer in a non-threatening way, talk to them as a peer, educate them about HIV self-testing, and encourage them to take control of their health.”(FSW-05)

“Hearing about self-testing from someone they trust makes it easier for them to accept and act on the information without feeling judged or afraid.”(FSW-05)

“Sometimes we listen to friends more than to health workers because friends know how to talk to us without judgment.”(FSW-14)

Integration into Public Health Systems and Insurance Schemes

“Providing free health schemes, like the National Health Insurance Scheme, will help raise awareness and increase uptake of HIV self-testing.”(FSW-10)

“If HIV self-testing is included in government health programs, people will see it as something important and normal, not something secret or shameful.”(FSW-04)

“It would also encourage more people to get tested regularly without worrying about financial barriers.”(FSW-13)

Community Awareness Campaigns and Practical Training

“They should create awareness through social media and radio stations because these are platforms that reach a lot of people easily. People often listen to the radio during their free time, whether at work or at home, and many of us are on social media every day.”(FSW-01)

“You can educate people about it and do some training because many people might not know how to use the kit properly on their own. Without proper guidance, they might make mistakes or misinterpret the results.”(FSW-01)

“If they show how to use it step by step, people will not be afraid to try it. People want to see how it works, not just hear about it.”(FSW-02)

“Something happened where I used to stay, two people engaged in sexual intercourse, and by mistake, the condom burst during the act. In situations like that, having an HIV self-testing kit on hand is very important. It would allow people to act immediately, check their status on the spot, and reduce the panic and delays that come with trying to find a clinic or waiting in long lines.”(FSW-01)

“It’s fast, and you receive your result immediately, which makes a big difference compared to going to a hospital.”(FSW-01)

“At least you know immediately what your result is and can decide what to do next instead of waiting days for hospital results.”(FSW-04)

4. Discussion

4.1. Triangulation of the Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

4.2. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO HIV/AIDS [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2024, p. 1. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/hivaids (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- WHO HIV Data and Statistics [Internet]. World Health Organization Fact Sheet. 2025, p. 1. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/strategic-information/hiv-data-and-statistics (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- UNAIDS Understanding Measures of Progress Towards the 95–95–95 HIV Testing, Treatment and Viral Suppression Targets [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/progress-towards-95-95-95_en.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- UNAIDS UNAIDS Fact Sheet 2024: Global HIV Statistics [Internet]. UNAIDS. 2024, pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Differentiated HIV Testing Services: Guidance for HIV Testing Services Among Priority Populations [Internet]. 2024; Chapter 6. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK605628/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- WHO Guidelines on HIV Self-Testing and Partner Notification. Supplement to Consolidated Guildelines on HIV Testing Services [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2016, pp. 1–104. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251655/9789241549868-eng.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Anyiam, F.E.; Sibiya, M.N.; Oladimeji, O. Factors Influencing the Acceptability and Uptake of HIV Self-Testing Among Priority Populations in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review. Public Health Rev. 2025, 46, 1608140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukashyaka, R.; Kaberuka, G.; Favina, A.; Lutasingwa, D.; Mulisa, F.; Turatsinze, E.; Karanja, A.; Kansiime, D.; Niyotwagira, E.; Ikuzo, B.; et al. Enhancing HIV self-testing uptake among university students in Rwanda: The proportion, barriers, and opportunities. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.; Thompson, N.; Choko, A.T.; Hlongwa, M.; Jolly, P.; Korte, J.E.; Conserve, D.F. HIV Self-Testing Uptake and Intervention Strategies Among Men in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 594298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapera, T.; Odimegwu, C.; Petlele, R.; Sello, M.V.; Dzomba, A.; Aladejebi, O.; Phiri, M. Intersecting epidemics: COVID-19 and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. A systematic review (2020–2022). J. Public Health Afr. 2023, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangendo, J.; A Obuku, E.; Kawooya, I.; Mukisa, J.; Nalutaaya, A.; Musewa, A.; Semitala, F.C.; A Karamagi, C.; Kalyango, J.N. Diagnostic accuracy and acceptability of rapid HIV oral testing among adults attending an urban public health facility in Kampala, Uganda. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, N.; Koole, O.; Sausi, K.; Krows, M.; Schaafsma, T.; Van Heerden, A.; Shahmanesh, M.; van Rooyen, H.; Celum, C.; Barnabas, R.V.; et al. Secondary Distribution of HIV Self-Testing Kits to Social and Sexual Networks of PLWH in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. A Brief Report. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 855625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-García, D.F.; Santi-Rocca, J. Direct-to-Consumer Testing: A Game-Changer for STI Control and Public Health? A Critical Review of Advances Since the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Venereology 2024, 3, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indravudh, P.P.; Fielding, K.; Kumwenda, M.K.; Nzawa, R.; Chilongosi, R.; Desmond, N.; Nyirenda, R.; Johnson, C.C.; Baggaley, R.C.; Hatzold, K.; et al. Community-led delivery of HIV self-testing to improve HIV testing, ART initiation and broader social outcomes in rural Malawi: Study protocol for a cluster-randomised trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2019, 19, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yrene-Cubas, R.A.; Perez-Castilla, J.; Reynaga-Cottle, D.E.; Bringas, M.J.; Soriano-Moreno, D.R.; Fernandez-Guzman, D.; Gonzales-Zamora, J.A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV testing in Peru: An interrupted time series analysis from 2014 to 2022. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoni, R.; Cavallin, F.; Casigliani, V.; Zin, A.; Giannini, D.; Chaguruca, I.; Cinturao, V.; Chinene, F.; Brigadoi, G.; Donà, D.; et al. Assessing the resilience of HIV healthcare services provided to adolescents and young adults after the COVID-19 pandemic in the city of Beira (Mozambique): An interrupted time series analysis. AIDS Res. Ther. 2024, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehurutshi, A.; Farooqui, H.; Chivese, T. The Impact of COVID-19 on the HIV Cascade of Care in Botswana—An Interrupted Time Series. AIDS Behav. 2024, 28, 2630–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershow, R.B.; Broz, D.; Faucher, L.; Feelemyer, J.; Chapin-Bardales, J.; Group for the NHIVBSS. HIV Testing Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Among Persons who Inject Drugs—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 19 Cities, 2018 and 2022. AIDS Behav. 2025, 29, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangoya, D.; Moyo, E.; Murewanhema, G.; Moyo, P.; Chitungo, I.; Dzinamarira, T. The HIV/AIDS responses pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa: A basis for sustainable health system strengthening post–COVID-19. IJID Reg. 2023, 9, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, W.J.; Clark, L.V.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; © SAGE Publications Ltd 2019; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48 Pt 2, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USAID Sampling and Household Listing Manual: Demographic and Health Survey [Internet]. ICF International. 2012, pp. 1–2. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSM4/DHS6_Sampling_Manual_Sept2012_DHSM4.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Olakunde, B.O.; Alemu, D.; Conserve, D.F.; Mathai, M.; Mak’anyengo, M.O.; Jennings Mayo-Wilson, L. Awareness of and willingness to use oral HIV self-test kits among Kenyan young adults living in informal urban settlements: A cross-sectional survey. AIDS Care-Psychol. Socio-Med. Asp AIDS/HIV 2023, 35, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terefe, B.; Jembere, M.M.; Reda, G.B.; Asgedom, D.K.; Assefa, S.K.; Lakew, A.M. Knowledge, and utilization of HIV self-testing, and its associated factors among women in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from 21 countries demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, J.; Miruka, F.; Mugambi, M.; Fidhow, A.; Chepkwony, B.; Kitheka, F.; Ngugi, E.; Aoko, A.; Ngugi, C.; Waruru, A. Characteristics of users of HIV self-testing in Kenya, outcomes, and factors associated with use: Results from a population-based HIV impact assessment, 2018. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segawa, I.; Bakeera-Kitaka, S.; Ssebambulidde, K.; Muwonge, T.R.; Oriokot, L.; Ojiambo, K.O.; Mujugira, A. Factors associated with HIV self-testing among female university students in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. AIDS Res. Ther. 2022, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthiyane, H.R.; Makatini, Z.; Tsukulu, R.; Jeena, R.; Mutloane, M.; Giddings, D.; Mahlangu, S.; Likotsi, P.; Majavie, L.; Druker, T.; et al. HIV self-testing: A cross-sectional survey conducted among students at a tertiary institution in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2020. J. Public Health Afr. 2023, 14, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, G.; Koris, A.; Simms, V.; Bandason, T.; Sigwadhi, L.; Ncube, G.; Munyati, S.; Kranzer, K.; Ferrand, R.A. On Campus HIV Self-Testing Distribution at Tertiary Level Colleges in Zimbabwe Increases Access to HIV Testing for Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akweh, T.Y.; Adoku, E.; Mbiba, F.; Teyko, F.; Brinsley, T.Y.; Boakye, B.A.; Aboagye, R.G.; Amu, H. Prevalence and factors associated with knowledge of HIV Self-Test kit and HIV-Self Testing among Ghanaian women: Multi-level analyses using the 2022 Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholuenetale, M.; Nzoputam, C.I.; Okonji, O.C. Association between socio-economic factors and HIV self-testing knowledge amongst South African women. South Afr. J. HIV Med. 2022, 23, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.; Neuman, M.; MacPherson, P.; Choko, A.; Quinn, C.; Wong, V.J.; Hatzold, K.; Nyrienda, R.; Ncube, G.; Baggaley, R.; et al. Use and awareness of and willingness to self-test for HIV: An analysis of cross-sectional population-based surveys in Malawi and Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeleke, E.A.; Stephens, J.H.; Gesesew, H.A.; Gello, B.M.; Worsa, K.T.; Ziersch, A. A community-based study of intention to use HIV self-testing among young people in urban areas of southern Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Marley, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, W.; Rongbin, Y.; Fu, G. Determinants of Recent HIV Self-Testing Uptake Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Jiangsu Province, China: An Online Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 736440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachinemere, O.L.; Nyegenye, S.; Mwesigwa, A.; Bulus, N.G.; Gmanyami, J.M.; Mukisa, K.A.; Isiko, I. Trends in HIV-related knowledge, behaviors and determinants of HIV testing among adolescent women aged 15–24 in Nigeria. Trop Med. Health 2025, 53, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ky-Zerbo, O.; Desclaux, A.; Boye, S.; Vautier, A.; Rouveau, N.; Kouadio, B.A.; Fotso, A.S.; Pourette, D.; Maheu-Giroux, M.; Sow, S.; et al. Willingness to use and distribute HIV self-test kits to clients and partners: A qualitative analysis of female sex workers’ collective opinion and attitude in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Senegal. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 17455057221092268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.B.; Kintin, F.D.; Atchekpe, S.; Batona, G.; Béhanzin, L.; Guédou, F.A.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Alary, M. HIV self-testing implementation, distribution and use among female sex workers in Cotonou, Benin: A qualitative evaluation of acceptability and feasibility. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, K.; D’eLbée, M.; Dekova, R.; Sande, L.A.; Dube, L.; Masuku, S.; Dlamini, M.; Mangenah, C.; Mwenge, L.; Johnson, C.; et al. Costs of distributing HIV self-testing kits in Eswatini through community and workplace models. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 22 (Suppl. 1), 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empringham, B.; Karellis, A.; Kashkary, A.; D’sIlva, O.; Carmona, S.; Suarez, M.F.; Addae, A.; Pai, N.P.; Zwerling, A.A. How much does HIV self-testing cost in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of evidence from economic studies. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1135425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhune, V.; Sharma, M.; Masyuko, S.; Ngure, K.; Otieno, G.; Paladhi, U.R.; Katz, D.A.; Kariithi, E.; Farquhar, C.; Bosire, R. Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of Distributing HIV Self-Tests within Assisted Partner Services in Western Kenya. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwalya, C.; Simwinga, M.; Hensen, B.; Gwanu, L.; Hang’andu, A.; Mulubwa, C.; Phiri, M.; Hayes, R.; Fidler, S.; Mwinga, A.; et al. Social response to the delivery of HIV self-testing in households: Experiences from four Zambian HPTN 071 (PopART) urban communities. AIDS Res. Ther. 2020, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumwenda, M.K.; Johnson, C.C.; Choko, A.T.; Lora, W.; Sibande, W.; Sakala, D.; Indravudh, P.; Chilongosi, R.; Baggaley, R.C.; Nyirenda, R.; et al. Exploring social harms during distribution of HIV self-testing kits using mixed-methods approaches in Malawi. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnko, S.; Nyato, D.; Kuringe, E.; Casalini, C.; Shao, A.; Komba, A.; Changalucha, J.; Wambura, M. Female sex workers perspectives and concerns regarding HIV self-testing: An exploratory study in Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Jing, F.; Fan, C.; Dai, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lv, H.; He, X.; Wu, D.; Tucker, J.D.; et al. Social network strategies to distribute HIV self-testing kits: A global systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2024, 27, e26342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, H.; Mwerinde, O.; Ross, A.L.; Leach, R.; Corbett, E.L.; Hatzold, K.; Johnson, C.C.; Ncube, G.; Nyirenda, R.; Baggaley, R.C. The Self-Testing AfRica (STAR) Initiative: Accelerating global access and scale-up of HIV self-testing. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22 (Suppl. 1), e25249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nduhukyire, L.; Semitala, F.C.; Mutanda, J.N.; Muramuzi, D.; Ipola, P.A.; Owori, B.; Kabagenyi, A.; Nangendo, J.; Namutundu, J. Prevalence, associated factors, barriers and facilitators for oral HIV self-testing among partners of pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics in Wakiso, Uganda. AIDS Res. Ther. 2024, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indravudh, P.P.M.; Hensen, B.; Nzawa, R.B.; Chilongosi, R.B.; Nyirenda, R.M.; Johnson, C.C.M.; Hatzold, K.; Fielding, K.; Corbett, E.L.F.; Neuman, M.S. Who is Reached by HIV Self-Testing? Individual Factors Associated With Self-Testing Within a Community-Based Program in Rural Malawi. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 85, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njau, B.; Covin, C.; Lisasi, E.; Damian, D.; Mushi, D.; Boulle, A.; Mathews, C. A systematic review of qualitative evidence on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV self-testing in Africa. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliyasu, Z.; Haladu, Z.A.; Iliyasu, B.Z.; Kwaku, A.A.; Nass, N.S.; Amole, T.G.; Abdullahi, H.M.; Abdullahi, A.U.; Tsiga-Ahmed, F.I.; Abdullahi, A.; et al. A Qualitative Study of HIV Testing Experiences and HIV Self-Testing Perspectives among Men in Northern Nigeria. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2024, 2024, 8810141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, H.; Manyazewal, T.; Kajogoo, V.D.; Getachew Assefa, D.; Gugsa Bekele, J.; Tolossa Debela, D. Advances in HIV self-testing: Systematic review of current developments and the road ahead in high-burden countries of Africa. SAGE Open Med. 2023, 12, 20503121231220788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Unweighted Frequency (n) | Weighted Frequency (n) | Weighted Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current age | |||

| Mean ± SD | 29.43 ± 10.48 ∞ | ||

| Range | (15–64) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 185,411 | 185,411.2 | 31.2 |

| Female | 409,228 | 409,228.0 | 68.8 |

| Current marital status | |||

| Never in union | 198,070 | 199,780.7 | 33.6 |

| Married | 294,074 | 292,209.7 | 49.1 |

| Living with a partner | 60,424 | 60,508.35 | 10.2 |

| Widowed | 11,242 | 10,850.9 | 1.8 |

| Divorced | 10,883 | 10,849.5 | 1.8 |

| No longer living together/separated | 19,946 | 20,439.9 | 3.4 |

| Currently residing with husband/partner (n = 352,714) | |||

| Yes | 303,840 | 304,189.3 | 86.2 |

| No | 50,656 | 48,525.6 | 13.8 |

| Type of place of residence | |||

| Urban | 230,854 | 247,302.3 | 41.6 |

| Rural | 363,785 | 347,336.9 | 58.4 |

| Highest educational level | |||

| No education | 165,963 | 158,109.6 | 26.6 |

| Primary | 184,162 | 182,851.2 | 30.8 |

| Secondary | 204,768 | 208,284.4 | 35.0 |

| Higher | 39,743 | 45,389.9 | 7.6 |

| Wealth index combined (n = 594,639) | |||

| Poorest | 120,696 | 101,738.9 | 17.1 |

| Poorer | 113,720 | 109,177.8 | 18.4 |

| Middle | 117,999 | 115,520.8 | 19.4 |

| Richer | 117,448 | 126,987.3 | 21.4 |

| Richest | 124,776 | 141,214.4 | 23.7 |

| Variables | Unweighted Frequency (n) | Weighted Frequency (n) | Weighted Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good knowledge of HIV/AIDS transmission (n = 567,880.494) | |||

| Yes | 482,270 | 485,014.1 | 93.7 |

| No | 36,076 | 32,870.1 | 6.3 |

| Condom used during last sex with most recent partner (n = 424,130) | |||

| Yes | 49,585 | 50,753.9 | 12.0 |

| No | 373,816 | 373,376.9 | 88.0 |

| Ever been tested for HIV (n = 498,638) | |||

| Yes | 254,839 | 256,924.4 | 51.5 |

| No | 243,984 | 241,714.1 | 48.5 |

| Know a place to get HIV test (n = 369,284) | |||

| Yes | 302,192 | 303,118.3 | 82.1 |

| No | 64,693 | 66,166.4 | 17.9 |

| Received result from last HIV test (n = 256,924) | |||

| Yes | 244,801 | 246,785.6 | 96.1 |

| No | 10,038 | 10,138.9 | 3.9 |

| Fear of stigma (n = 392,989) | |||

| Yes | 30,8516 | 312,261.7 | 79.5 |

| No | 61,741 | 60,740.5 | 15.5 |

| Don’t know/not sure/depends | 20,529 | 19,987.2 | 5.1 |

| Ever heard of HIVST (n = 395,614) | |||

| Yes | 61,127 | 64,344.7 | 16.3 |

| No | 33,2671 | 33,1270.1 | 83.7 |

| Ever used HIVST (n = 395,614) | |||

| Yes | 9955 | 9955.6 | 2.5 |

| No | 385,659 | 385,659.2 | 97.5 |

| Variables | cOR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 0.009 * | 0.89 (0.84–0.94) | 0.001 * |

| Female R | - | - | - | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never in union R | - | - | - | - |

| Married | 0.57 (0.52–0.63) | <0.001 * | 1.95 (1.78–2.15) | 0.001 * |

| Living with partner | 0.65 (0.60–0.71) | <0.001 * | 1.35 (1.23–1.47) | 0.001 * |

| Widowed | 0.51 (0.46–0.57) | <0.001 * | 1.86 (1.67–2.08) | 0.001 * |

| Divorced | 0.39 (0.32–0.48) | <0.001 * | 1.70 (1.38–2.11) | 0.001 * |

| Currently residing with Partner | ||||

| Yes | 0.55 (0.52–0.59) | <0.001 * | 1.58 (1.48–1.68) | 0.001 * |

| No R | - | - | - | - |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 2.21 (2.12–2.30) | <0.001 * | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) | 0.006 * |

| Rural R | - | - | - | - |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| No education R | - | - | - | - |

| Primary | 0.08 (0.08–0.09) | <0.001 * | 2.36 (2.19–2.55) | 0.001 * |

| Secondary | 0.12 (0.11–0.12) | <0.001 * | 4.70 (4.28–5.17) | 0.001 * |

| Higher | 0.26 (0.24–0.27) | <0.001 * | 7.36 (6.62–8.18) | 0.001 * |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorest R | - | - | - | - |

| Poorer | 0.26 (0.25–0.29) | <0.001 * | 1.66 (1.54–1.79) | <0.001 * |

| Middle | 0.35 (0.33–0.38) | <0.001 * | 2.46 (2.24–2.70) | <0.001 * |

| Richer | 0.39 (0.37–0.42) | <0.001 * | 2.65 (2.41–2.92) | <0.001 * |

| Richest | 0.62 (0.58–0.65) | <0.001 * | 3.28 (2.95–3.65) | <0.001 * |

| Variables | cOR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good knowledge of HIV/AIDS transmission | ||||

| Yes | 54.02 (23.51–124.14) | <0.001 * | 33.43 (11.03–101.24) | <0.001 * |

| No R | - | - | ||

| Condom used (last sex) | ||||

| Yes | 1.56 (1.47–1.65) | <0.001 * | 1.49 (1.15–1.93) | 0.002 * |

| No R | - | - | - | - |

| Ever tested for HIV | ||||

| Yes | 5.65 (5.32–6.01) | <0.001 * | 3.33 (3.08–3.60) | <0.001 * |

| No R | - | - | - | - |

| Know test location | ||||

| Yes | 3.99 (3.59–4.44) | <0.001 * | 1.52 (1.33–1.72) | <0.001 * |

| No R | - | - | - | - |

| Received last test result | ||||

| Yes | 2.83 (2.37–3.38) | <0.001 * | 2.22 (1.84–2.68) | <0.001 * |

| No R | - | - | - | - |

| Fear of stigma | ||||

| Yes | 2.92 (2.46–3.48) | <0.001 * | 0.49 (0.41–0.59) | <0.001 * |

| No | 2.05 (1.70–2.47) | <0.001 * | 0.34 (0.29–0.41) | <0.001 * |

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–30 | 12 | 80.0 |

| 31–40 | 3 | 20.0 |

| Mean ± SD | 29.33 ± 4.2 ∞ | |

| Range | (23–38) | |

| Religion | ||

| Christian | 11 | 73.3 |

| Muslim | 1 | 6.7 |

| No religious affiliation | 3 | 20.0 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 10 | 66.7 |

| Living with partner | 1 | 6.7 |

| I choose not to answer | 4 | 26.7 |

| Have children | ||

| Yes | 1 | 6.7 |

| No | 11 | 73.3 |

| I choose not to answer | 3 | 20.00 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Secondary school (high school) | 7 | 46.7 |

| Completed OND | 2 | 13.3 |

| Completed Bachelor’s degree | 6 | 40.0 |

| Engaged in any other occupation | ||

| Yes | 8 | 53.3 |

| No | 7 | 46.7 |

| Nature of occupation (n = 8) | ||

| Employed or self-employed full-time work | 1 | 12.5 |

| Employed or self-employed part-time work | 7 | 87.5 |

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Empowerment through HIVST | - Privacy and Confidentiality |

| - Autonomy and Personal Control | |

| - Convenience and Rapid Results | |

| Barriers and Vulnerabilities Post-COVID-19 | - Financial Barriers and Affordability Concerns |

| - Fear, Anxiety, and Emotional Distress | |

| - Perceived Stigma and Confidentiality Risks | |

| Community-Driven Strategies for Health Promotion | - Peer-to-Peer Support and Education |

| - Integration of HIVST into Public Health Systems and Insurance Schemes | |

| - Community Awareness Campaigns and Practical Training |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sibiya, M.N.; Anyiam, F.E.; Oladimeji, O. Empowering Vulnerable Communities Through HIV Self-Testing: Post-COVID-19 Strategies for Health Promotion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111616

Sibiya MN, Anyiam FE, Oladimeji O. Empowering Vulnerable Communities Through HIV Self-Testing: Post-COVID-19 Strategies for Health Promotion in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111616

Chicago/Turabian StyleSibiya, Maureen Nokuthula, Felix Emeka Anyiam, and Olanrewaju Oladimeji. 2025. "Empowering Vulnerable Communities Through HIV Self-Testing: Post-COVID-19 Strategies for Health Promotion in Sub-Saharan Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111616

APA StyleSibiya, M. N., Anyiam, F. E., & Oladimeji, O. (2025). Empowering Vulnerable Communities Through HIV Self-Testing: Post-COVID-19 Strategies for Health Promotion in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111616