Influence of Emergency Situations on Maternal and Infant Nutrition: Evidence and Policy Implications from Hurricane John in Guerrero, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

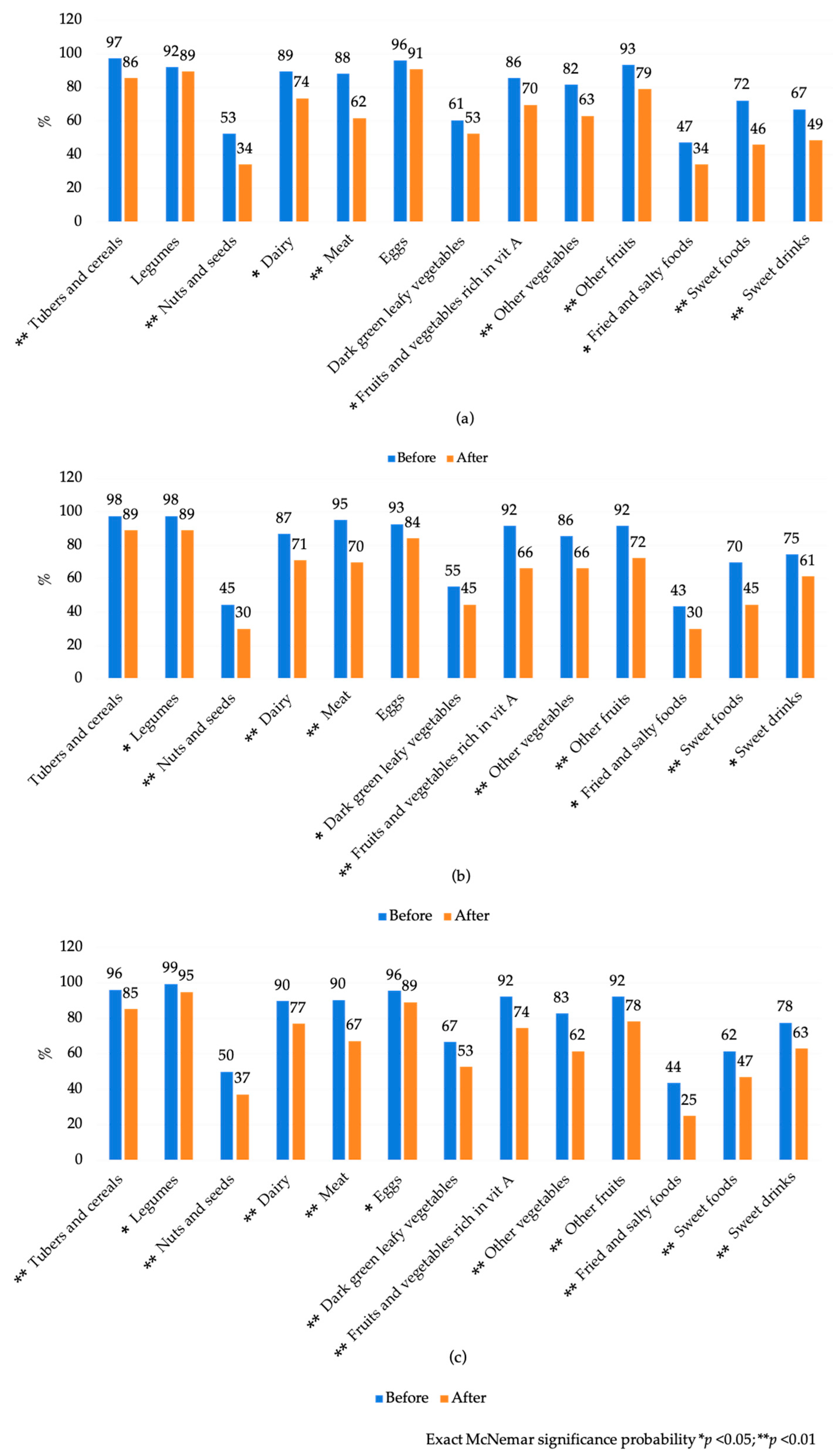

3. Results

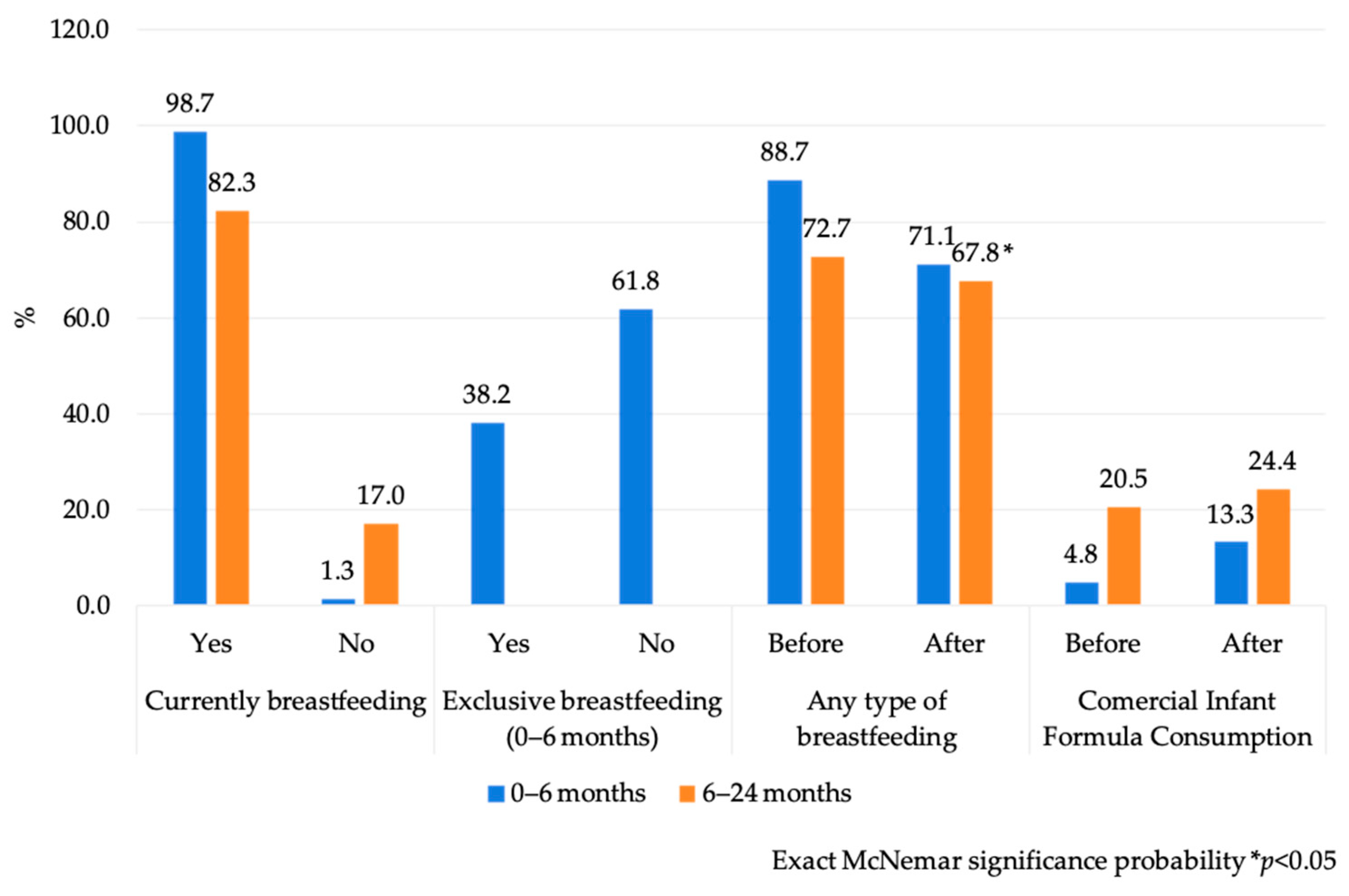

3.1. Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices

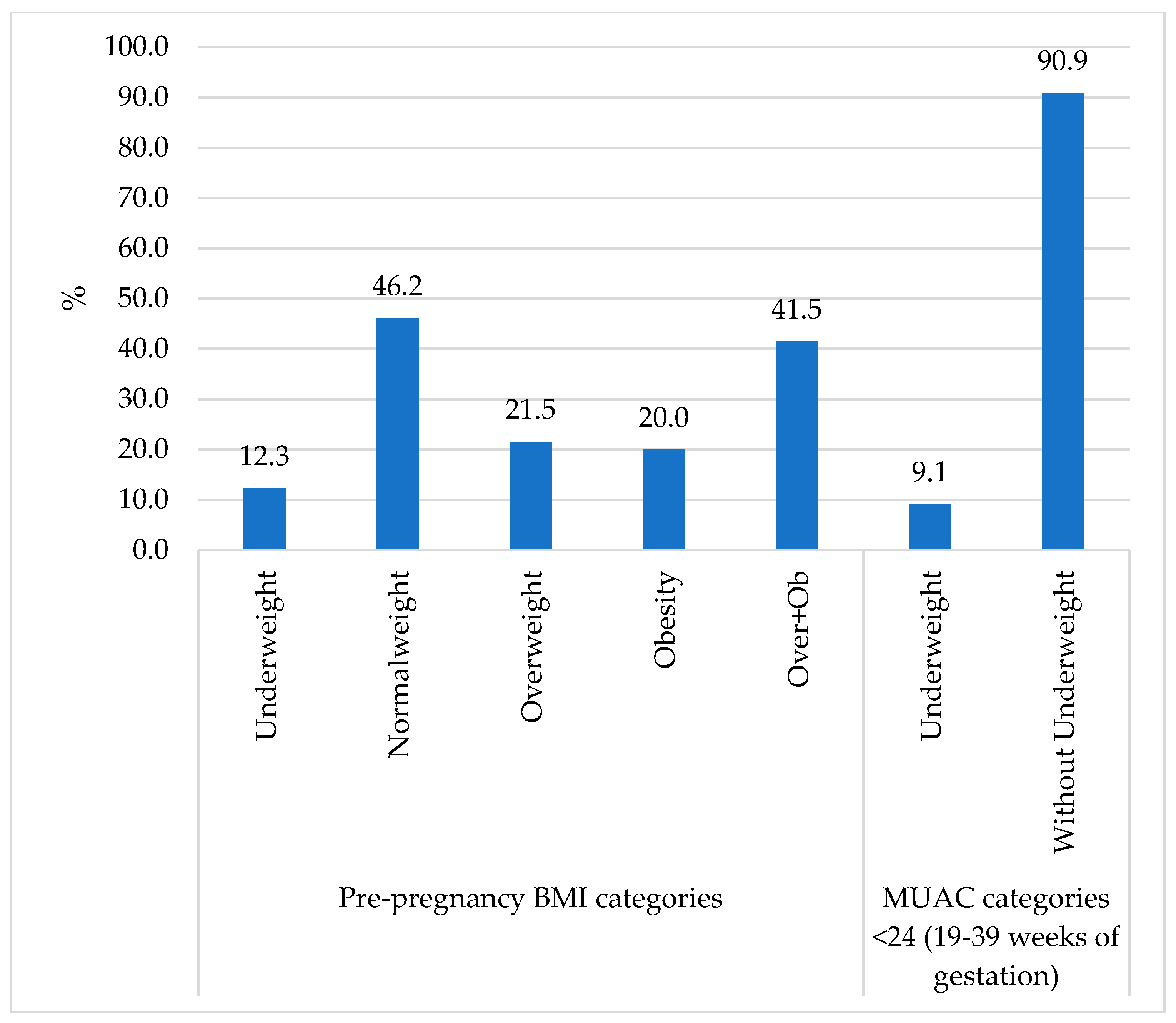

3.2. Maternal and Infant Nutritional Status

4. Discussion

5. Lessons Learned and Key Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMAI | Mexican Association of Market Research Agencies |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BMS | Breastmilk Substitute |

| CDC | Center for Disease Control |

| CIF | Commercial Infant Formula |

| ENSANUT | National Health and Nutrition Survey |

| IFE | Infant Feeding in Emergencies |

| IYCF-E | Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies |

| IYCF | Infant and Young Child Feeding |

| MAM | Moderate Acute Malnutrition |

| MMSs | Multiple Micronutrient Supplements |

| MNPs | Micronutrient Powders |

| MUAC | Mid-Upper Arm Circumference |

| NIPH | National Institute of Public Health of Mexico |

| OG-IFE | Operational Guidance on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies |

| REDCap RUFT | Research Electronic Data Capture Ready-to-use therapeutic foods |

| SAM | Severe Acute Malnutrition |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

| SSGro | Secretaría de Salud de Guerrero (by its acronym in Spanish) |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| WASH | Water, Sanitation and Hygiene |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Pregnant Women (n = 76) | Caregivers from Infants < 6 m (n = 83) | Caregivers from Children 6–24 m (n = 156) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | p Value * | Before | After | p Value * | Before | After | p Value * | |||||||

| Access to drinking water | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Yes | 60 | 79.0 | 22 | 29.0 | 0.000 | 58 | 69.9 | 27 | 32.5 | 0.000 | 117 | 75.0 | 43 | 27.6 | 0.000 |

| No | 16 | 21.1 | 53 | 69.7 | 25 | 30.1 | 56 | 67.5 | 39 | 25.0 | 113 | 72.4 | |||

| Water to meet needs such as: | |||||||||||||||

| Drinking | 72 | 94.7 | 40 | 52.6 | 0.000 | 79 | 96.3 | 48 | 58.5 | 0.000 | 148 | 94.3 | 102 | 65.0 | 0.000 |

| Cooking | 74 | 97.4 | 39 | 51.3 | 0.000 | 80 | 97.6 | 48 | 58.5 | 0.000 | 152 | 96.8 | 105 | 66.9 | 0.000 |

| Personal hygiene (washing or bathing) | 75 | 98.7 | 42 | 55.3 | 0.000 | 75 | 91.5 | 42 | 51.2 | 0.000 | 143 | 91.1 | 85 | 54.1 | 0.000 |

| Other household purposes | 75 | 98.7 | 33 | 43.4 | 0.000 | 70 | 85.4 | 27 | 32.9 | 0.000 | 138 | 87.9 | 81 | 51.6 | 0.000 |

| There is not enough water to meet any of the above needs | 2 | 2.6 | 30 | 39.5 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.2 | 25 | 30.5 | 0.000 | 3 | 1.9 | 43 | 27.4 | 0.000 |

| Water quality | |||||||||||||||

| Good (no smell, color or taste) | 63 | 82.9 | 21 | 27.6 | ** 0.001 | 61 | 73.2 | 32 | 38.6 | ** 0.001 | 116 | 74.8 | 52 | 33.3 | ** 0.001 |

| Regular (the water is cloudy) | 13 | 17.1 | 30 | 39.5 | 22 | 26.8 | 33 | 39.8 | 36 | 23.2 | 70 | 45.5 | |||

| Poor (has smell, color or taste) | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 32.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 21.7 | 3 | 1.9 | 33 | 21.2 | |||

| Diseases associated with water consumption | |||||||||||||||

| Diarrheal diseases (Yes) | 8 | 10.5 | 9 | 11.8 | ** 0.32 | 6 | 7.3 | 6 | 7.3 | ** 0.99 | 17 | 10.8 | 28 | 17.8 | ** 0.012 |

| Diseases such as dysentery, typhoid fever, cholera, hepatitis (Yes) | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.6 | 2 | 2.4 | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | |||

| Skin infections (Yes) | 1 | 1.3 | 7 | 9.2 | 2 | 2.4 | 4 | 4.9 | 1 | 0.6 | 10 | 6.4 | |||

| Pregnant Women (n = 76) | Caregivers 0–6 Months (n = 83) | Caregivers 6–24 Months (n = 156) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||||||||||

| Group | n | % | n | % | p Value * | n | % | n | % | p Value * | n | % | n | % | p Value * |

| Tubers and cereals | 74 | 97.4 | 65 | 85.5 | 0.004 | 81 | 97.6 | 74 | 89.2 | 0.065 | 150 | 96.2 | 133 | 85.3 | 0.001 |

| Legumes | 70 | 92.1 | 68 | 89.5 | 0.727 | 81 | 97.6 | 74 | 89.2 | 0.039 | 155 | 99.4 | 148 | 94.9 | 0.039 |

| Nuts and seeds | 40 | 52.6 | 26 | 34.2 | 0.003 | 37 | 44.6 | 25 | 30.1 | 0.004 | 78 | 50.0 | 58 | 37.2 | 0.003 |

| Dairy | 68 | 89.5 | 56 | 73.7 | 0.023 | 72 | 86.8 | 59 | 71.1 | 0.002 | 140 | 89.7 | 120 | 76.9 | 0.001 |

| Meat | 67 | 88.2 | 47 | 61.8 | 0.000 | 79 | 95.2 | 58 | 69.9 | 0.000 | 141 | 90.4 | 105 | 67.3 | 0.000 |

| Eggs | 73 | 96.1 | 69 | 90.8 | 0.289 | 77 | 92.8 | 70 | 84.3 | 0.092 | 149 | 95.5 | 139 | 89.1 | 0.031 |

| Dark green leafy vegetables | 46 | 60.5 | 40 | 52.6 | 0.210 | 46 | 55.4 | 37 | 44.6 | 0.035 | 104 | 66.7 | 82 | 52.6 | 0.001 |

| Fruits and vegetables rich in vit A | 65 | 85.5 | 53 | 69.7 | 0.012 | 76 | 91.6 | 55 | 66.3 | 0.000 | 144 | 92.3 | 116 | 74.4 | 0.000 |

| Other vegetables | 62 | 81.6 | 48 | 63.2 | 0.001 | 71 | 85.5 | 55 | 66.3 | 0.001 | 129 | 82.7 | 96 | 61.5 | 0.000 |

| Other fruits | 71 | 93.4 | 60 | 79.0 | 0.001 | 76 | 91.6 | 60 | 72.3 | 0.000 | 144 | 92.3 | 122 | 78.2 | 0.000 |

| Fried and salty foods | 36 | 47.4 | 26 | 34.2 | 0.031 | 36 | 43.4 | 25 | 30.1 | 0.027 | 68 | 43.6 | 39 | 25.0 | 0.000 |

| Sweet foods | 55 | 72.4 | 35 | 46.1 | 0.000 | 58 | 69.9 | 37 | 44.6 | 0.000 | 96 | 61.5 | 73 | 46.8 | 0.000 |

| Sweet drinks | 51 | 67.1 | 37 | 48.7 | 0.004 | 62 | 74.7 | 51 | 61.5 | 0.043 | 121 | 77.6 | 98 | 62.8 | 0.000 |

| Before | After | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Meals/Day | n | % | n | % | Bowker χ2 (p Value) |

| Pregnant women (n = 76) | 1 | 2 | 2.63 | 5 | 6.6 | 26.3 (p = 0.003) |

| 2 | 18 | 23.7 | 39 | 51.3 | ||

| 3 | 49 | 64.5 | 30 | 39.5 | ||

| 4 | 6 | 7.9 | 2 | 2.6 | ||

| 5 | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Caregivers of children < 6 months (n = 83) | 1 | 1 | 1.2 | 6 | 7.3 | 43.0 (p < 0.001) |

| 2 | 18 | 21.7 | 49 | 59.8 | ||

| 3 | 54 | 65.1 | 27 | 32.9 | ||

| 4 | 8 | 9.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Caregivers of children 6–24 months (n = 156) | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 9.9 | 68.3 (p < 0.001) |

| 2 | 36 | 23.1 | 95 | 62.5 | ||

| 3 | 105 | 67.3 | 39 | 25.7 | ||

| 4 | 15 | 9.6 | 3 | 2.0 | ||

| All groups | 1 | 3 | 1.0 | 26 | 8.4 | 150.7 (p < 0.001) |

| 2 | 72 | 22.9 | 183 | 59.0 | ||

| 3 | 208 | 66.0 | 96 | 31.0 | ||

| 4 | 29 | 9.2 | 5 | 1.6 | ||

| 5 | 3 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

References

- World Health Organization. Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management Framework; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326106/9789241516181-eng.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- World Health Organization; United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding; World Health Organization Stylus Pub., LLC [distributor]: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- IFE Core Group Operational Guidance on Infant Feeding in Emergencies (OG-IFE) version 3.0 (Oct 2017). 2017. Available online: https://www.ennonline.net/resource/ife/operational-guidance-infant-feeding-emergencies-og-ife-version-30-oct-2017 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Unar-Munguía, M.; Hubert, C.; Bonvecchio-Arenas, A.; Vázquez-Salas, R.A. Acceso a servicios de salud prenatal y para primera infancia. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, s55–s64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, A.; Kueter, A.M.; Ariful, S.; Rahaman, H.; Iellamo, A.; Mothabbir, G. Appropriate Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices in an Emergency for Non-Breastfed Infants Under Six Months: The Rohingya Experience. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendavid, E.; Boerma, T.; Akseer, N.; Langer, A.; Malembaka, E.B.; Okiro, E.A.; Wise, P.H.; Heft-Neal, S.; Black, R.; Bhutta, Z.; et al. The effects of armed conflict on the health of women and children. Lancet 2021, 397, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyozuka, H.; Yasuda, S.; Kawamura, M.; Nomura, Y.; Fujimori, K.; Goto, A.; Yasumura, S.; Abe, M. Impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on feeding methods and newborn growth at 1 month postpartum: Results from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2016, 55, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudhon, C.; Benelli, P.; Maclaine, A.; Harrigan, P.; Frize, J. Informing infant and young child feeding programming in humanitarian emergencies: An evidence map of reviews including low and middle income countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffalli, S.; Villalobos, C. Recent Patterns of Stunting and Wasting in Venezuelan Children: Programming Implications for a Protracted Crisis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 638042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doocy, S.; Ververs, M.T.; Spiegel, P.; Beyrer, C. The food security and nutrition crisis in Venezuela. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 226, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.H.; Iellamo, A.; Ververs, M. Barriers and challenges of infant feeding in disasters in middle- and high-income countries. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1981.

- Lutter, C.K.; Hernández-Cordero, S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.; Lara-Mejía, V.; Lozada-Tequeanes, A.L. Violations of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes: A multi-country analysis. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hipgrave, D.B.; Assefa, F.; Winoto, A.; Sukotjo, S. Donated breast milk substitutes and incidence of diarrhoea among infants and young children after the May 2006 earthquake in Yogyakarta and Central Java. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creek, T.L.; Kim, A.; Lu, L.; Bowen, A.; Masunge, J.; Arvelo, W.; Smit, M.; MacH, O.; Legwaila, K.; Motswere, C.; et al. Hospitalization and mortality among primarily nonbreastfed children during a large outbreak of diarrhea and malnutrition in Botswana, 2006. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 53, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake Mudiyanselage, S.; Davis, D.; Kurz, E.; Atchan, M. Infant and young child feeding during natural disasters: A systematic integrative literature review. Women Birth 2022, 35, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guiding Principles for Feeding Infants and Young Children During Emergencies; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Bilgin, D.D.; Karabayır, N. Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies: A Narrative Review. Turkish Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 59, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toole, M.J.; Waldman, R.J. The public health aspects of complex emergencies and refugee situations. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1997, 18, 283–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcántara-Ayala, I. Desastres en México: Mapas y apuntes sobre una historia inconclusa. Investig. Geográficas 2019, 100, e60025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S. La huella de Otis en Acapulco: Un Análisis de las Secuelas Políticas, Económicas y Sociales; Integralia Consultores: Mexico City, México, 2024; Available online: https://integralia.com.mx/web/la-huella-de-otis-en-acapulco-un-analisis-de-las-secuelas-politicas-economicas-y-sociales/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Guillén, B. El Balance Final del Huracán ‘John’ en Guerrero: 270.000 Afectados y 23 Fallecidos. El País 2024, 1–1. Available online: https://elpais.com/mexico/2024-10-04/el-balance-final-del-huracan-john-en-guerrero-270000-afectados-y-23-fallecidos.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com&event=go&event_log=go&prod=REGCRARTMX&o=cerradomx (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Sphere Association. The Sphere Handbook Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response, 4th ed.; Sphere Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://spherestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/Sphere-Handbook-2018-EN.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Mapa de Guerrero. División Municipal; INEGI: Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; Available online: https://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/imprime_tu_mapa/doc/gro-mpios-sn.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Anand, H.; Swarup, S.; Shafiee-Jood, M.; Alemazkoor, N. Understanding of income and race disparities in hurricane evacuation is contingent upon study case and design. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regional Group for Integrated Nutrition Resilience (GRIN-LAC) for Latin American and the Caribbean Rapid Nutrition Assessment. Observations Guide. Nutrition in Emergency Series—Emergency Nutrition Response. 2018. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/regional-group-integrated-nutrition-resilience-grin-lac-latin-american-and-caribbean-nutrition-emergency-series-emergency-nutrition-response-rapid-nutrition-assessment-observations-guide?_gl=1*1ick42v*_ga*MTM1Nzc1ODgyMC4 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Asociación Mexicana de Agencias de Investigación de Mercado y Opinión (AMAI). Cuestionario Para la Aplicación de la Regla AMAI 2022 y Tabla de Clasificación; AMAI: Mexico City, Mexico, 2022; Available online: https://www.amai.org/descargas/CUESTIONARIO_AMAI_2022.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- González-Castell, L.D.; Unar-Munguía, M.; Bonvecchio-Arenas, A.; Ramírez-Silva, I.; Lozada-Tequeanes, A.L. Prácticas de lactancia materna y alimentación complementaria en menores de dos años de edad en México. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, s204–s210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization [WHO]; The United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Definitions and Measurement Methods; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/340706 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. The Management of Nutrition in Major Emergencies; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241545208 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2008, 42, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Recommendations for Data Collection, Analysis and Reporting on Anthropometric Indicators in Children Under 5 Years Old; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515559 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- De Onis, M.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline on the Prevention and Management of Wasting and Nutritional oedema (Acute MALNUTRITION) in Infants and Children Under 5 Years; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240082830 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud Pública; Servicio Nacional de Salud; UNICEF; USAID. Guía Informativa Para Personal de Salud y Promotores Comunitarios. Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de la Desnutrición Aguda en el Primer Nivel de Atención y en la Comunidad; UNICEF-República Dominicana: Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/dominicanrepublic/informes/guia-informativa-para-personal-de-salud-y-promotores-comunitarios (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Programa Nacional de Protección Civil 2022–2024. Diario Oficial de la Federación; México. 2022. Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5673256&fecha=05/12/2022#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Castaldo, M.; Marrone, R.; Costanzo, G.; Mirisola, C. Clinical Practice and Knowledge in Caring: Breastfeeding Ties and the Impact on the Health of Latin-American Minor Migrants. J. Immigr. Minor. Heal. 2015, 17, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoya, M.A.; Golden, K.; Ngnie-Teta, I.; Moreaux, M.D.; Mamadoultaibou, A.; Koo, L.; Boyd, E.; Beauliere, J.M.; Lesavre, C.; Marhone, J.P. Protecting and improving breastfeeding practices during a major emergency: Lessons learnt from the baby tents in Haiti. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartick, M.; Zimmerman, D.R.; Sulaiman, Z.; El Taweel, A.; AlHreasy, F.; Barska, L.; Fadieieva, A.; Massry, S.; Dahlquist, N.; Mansovsky, M.; et al. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Position Statement: Breastfeeding in Emergencies. Breastfeed. Med. 2024, 19, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, L.E.; Boyd, E. Challenges to the Programmatic Implementation of Ready to Use Infant Formula in the Post-Earthquake Response, Haiti, 2010: A Program Review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Iellamo, A. Wet nursing and donor human milk sharing in emergencies and disasters: A review. Breastfeed. Rev. 2020, 28, 17. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]. Guidance on the Procurement and Use of Breastmilk Substitutes in Humanitarian Settings Version 2.0; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Pregnant Women (n = 76) | Caregivers from Infants < 6 m (n = 83) | Caregivers from Children 6–24 m (n = 156) | Total (n = 315) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Health Jurisdiction | ||||||||

| Acapulco | 59 | 77.6 | 62 | 74.7 | 114 | 73.1 | 235 | 74.6 |

| Costa Grande | 17 | 22.4 | 21 | 25.3 | 42 | 26.9 | 80 | 25.4 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 25.9 | 6.3 | 26.2 | 6.2 | 29.3 | 8.7 | 27.7 | 7.7 |

| Categorical age | ||||||||

| 16–24 | 36 | 47.4 | 35 | 42.2 | 50 | 32.0 | 121 | 38.4 |

| 25–29 | 23 | 30.3 | 24 | 28.9 | 38 | 24.4 | 85 | 27.0 |

| 30–39 | 14 | 18.4 | 21 | 25.3 | 54 | 34.6 | 89 | 28.2 |

| >40 | 3 | 4.0 | 3 | 3.6 | 14 | 9.0 | 20 | 6.3 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Free union (Cohabiting) | 38 | 50.0 | 48 | 57.8 | 68 | 43.6 | 154 | 48.9 |

| Separated/divorced | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 3.8 | 7 | 2.2 |

| Married | 34 | 44.7 | 26 | 31.3 | 77 | 49.4 | 137 | 43.5 |

| Single woman | 3 | 4.0 | 8 | 9.6 | 5 | 3.2 | 16 | 5.1 |

| Widow | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.32 | 0.3 |

| Education | ||||||||

| None | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Primary School | 11 | 14.5 | 7 | 8.4 | 19 | 12.2 | 37 | 11.7 |

| Secondary School | 33 | 43.4 | 28 | 33.7 | 61 | 39.1 | 122 | 38.7 |

| High School | 29 | 38.2 | 37 | 44.6 | 54 | 34.6 | 120 | 38.1 |

| Technical or commercial | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 2 | 2.6 | 10 | 12.0 | 18 | 11.5 | 30 | 9.5 |

| Socioeconomic Level | ||||||||

| High | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Medium | 14 | 18.4 | 12 | 14.5 | 37 | 23.7 | 63 | 20 |

| Low | 53 | 69.7 | 66 | 79.5 | 94 | 60.3 | 213 | 67.6 |

| Very low | 9 | 11.8 | 5 | 6.0 | 24 | 15.4 | 38 | 12.1 |

| Total (n = 315) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | p Value * | |||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Access to drinking water | |||||

| Yes | 235 | 74.6 | 92 | 29.3 | 0.000 |

| No | 80 | 25.4 | 222 | 70.7 | |

| Water to meet needs such as: | |||||

| Drinking | 299 | 94.9 | 190 | 60.3 | 0.000 |

| Cooking | 306 | 97.1 | 192 | 61 | 0.000 |

| Personal hygiene (washing or bathing) | 293 | 93 | 169 | 53.7 | 0.000 |

| Other household purposes (cleaning the house, floor, etc.) | 283 | 89.8 | 141 | 44.8 | 0.000 |

| There is not enough water to meet any of the above needs | 6 | 1.9 | 98 | 31.1 | 0.000 |

| Water quality | |||||

| Good (no smell, color or taste) | 240 | 76.2 | 105 | 33.3 | ** 0.001 |

| Regular (the water is cloudy) | 71 | 22.5 | 133 | 42.2 | |

| Poor (has smell, color or taste) | 3 | 1 | 76 | 24.1 | |

| Diseases associated with water consumption | |||||

| Diarrheal diseases (Yes) | 31 | 9.8 | 43 | 13.7 | ** 0.01 |

| Diseases such as dysentery, typhoid fever, cholera, hepatitis (Yes) | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Skin infections (Yes) | 4 | 1.3 | 21 | 6.7 | |

| <6 m (n = 83) | 6–24 m (n = 156) * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | ||||

| L/A Categories | n | % | n | % |

| Adequate | 67 | 80.7 | 89 | 58.6 |

| Low length risk | 10 | 12.0 | 42 | 27.6 |

| Low length | 4 | 4.8 | 15 | 9.9 |

| Severely low length | 2 | 2.4 | 6 | 4.0 |

| W/L Categories | n | % | n | % |

| Obesity | - | - | 2 | 1.3 |

| Overweight | 5 | 6.0 | 11 | 7.1 |

| Risk of Overweight | 17 | 20.5 | 19 | 12.2 |

| Adequate | 52 | 62.7 | 101 | 64.7 |

| Risk of Acute Malnutrition | 5 | 6.0 | 19 | 12.2 |

| MAM | 3 | 3.6 | 4 | 2.6 |

| SAM | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| MUAC Categories | n | % | n | % |

| Normal | 76 | 91.6 | 143 | 91.7 |

| With malnutrition | 7 | 8.4 | - | - |

| Risk of Acute Malnutrition | - | - | 11 | 7.1 |

| MAM | - | - | 2 | 1.3 |

| Key Actors | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Federal Government and Decision-Makers |

|

| Ministry of Health |

|

| Civil Protection, Red Cross, and Emergency Response Agencies |

|

| Army and Food Distribution Agencies (e.g., DIF) |

|

| Primary Healthcare Units |

|

| Local Governments and Municipalities |

|

| All Levels of Government |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim-Herrera, E.; Lozada-Tequeanes, A.L.; González-Castell, D.; Chávez-Muñoz, E.A.; Alvarado-Casas, R.; Rafalli-Arismendi, S.; Sachse-Aguilera, M.; De Bustos, C.; Bonvecchio-Arenas, A. Influence of Emergency Situations on Maternal and Infant Nutrition: Evidence and Policy Implications from Hurricane John in Guerrero, Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111615

Kim-Herrera E, Lozada-Tequeanes AL, González-Castell D, Chávez-Muñoz EA, Alvarado-Casas R, Rafalli-Arismendi S, Sachse-Aguilera M, De Bustos C, Bonvecchio-Arenas A. Influence of Emergency Situations on Maternal and Infant Nutrition: Evidence and Policy Implications from Hurricane John in Guerrero, Mexico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111615

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim-Herrera, Edith, Ana Lilia Lozada-Tequeanes, Dinorah González-Castell, Edgar Arturo Chávez-Muñoz, Rocío Alvarado-Casas, Susana Rafalli-Arismendi, Matthias Sachse-Aguilera, Cecilia De Bustos, and Anabelle Bonvecchio-Arenas. 2025. "Influence of Emergency Situations on Maternal and Infant Nutrition: Evidence and Policy Implications from Hurricane John in Guerrero, Mexico" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111615

APA StyleKim-Herrera, E., Lozada-Tequeanes, A. L., González-Castell, D., Chávez-Muñoz, E. A., Alvarado-Casas, R., Rafalli-Arismendi, S., Sachse-Aguilera, M., De Bustos, C., & Bonvecchio-Arenas, A. (2025). Influence of Emergency Situations on Maternal and Infant Nutrition: Evidence and Policy Implications from Hurricane John in Guerrero, Mexico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111615