“Without Filters” Nurse and Healthcare Worker Personal Protective Equipment Injuries and the COVID-19 Experience: An International Social Media Ethnographic Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Approach

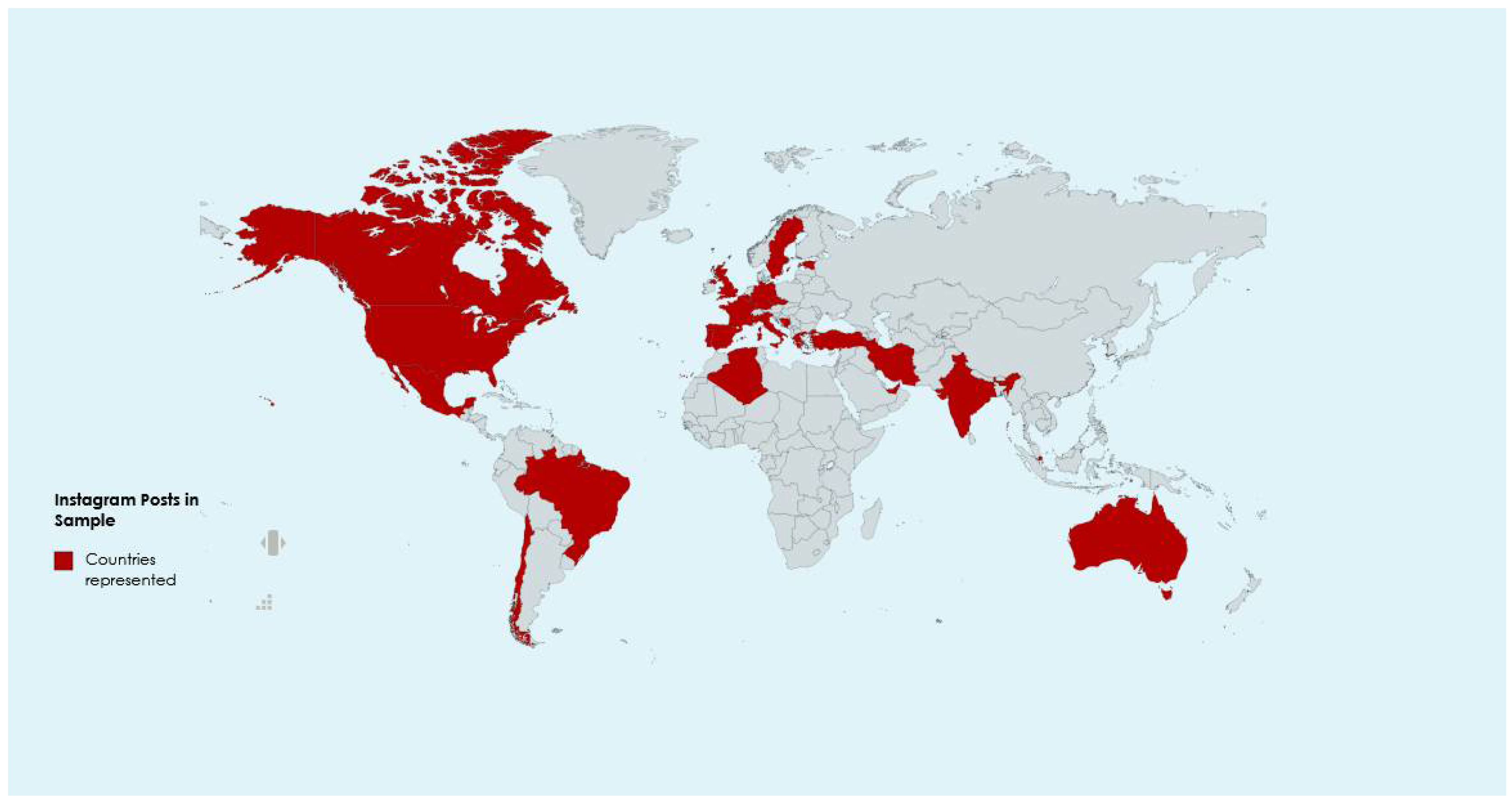

2.2. Setting and Sample

2.3. Ethics Statement

2.4. Data Collection Methods and Instruments

3. Results

3.1. Grueling Shifts Filled with Unimaginable Loss

“… i’m honestly too tired, i have no energy left, these shifts are probably the worst we all had in our lives.

You People out there don’t realize how tragic and dangerous this situation is. …”—England

“…I work on a surgical unit, which was converted into one of the first COVID units in my hospital. I took my first COVID patient almost 2 months ago, and it feels like it’s been about 12 years since I’ve taken care of anything other than COVID. I have seen more death in 2 months than I have in my 2 short years as a nurse. After most of my shifts, I go home and cry. While many of the patients are elderly with comorbidities, putting them at higher risk of dying, it was not their time to go…”—USA

“…I have never been so worn out from an overnight shift. Each time before I walk into a different patients room, I have to regown into PPE. I can’t count how many times I’ve done this last night. My hands are dried out. I am wearing a #N-95 mask I can barely breathe in and a second mask over it the whole shift. I am sweating wearing a gown, white body suit, shoe covers, switching gloves every 5 minutes, a hat, and goggles sticking to my face for 8 hours straight.

Last night, i heard “code blue-COVID” 2 times during my shift within 2 hours.

Now I’m scared. Our hospital has 2 floors flooded with 25 positive COVID patients each. We’re running low on supplies, packing out our ER and are running out of beds to admit patients because of this crisis. …”—USA

“…In march I’ve worked 27 days of 31!! I have to wrk this weekend… I hope I can do 4 days rest at the end of april…”—Italy

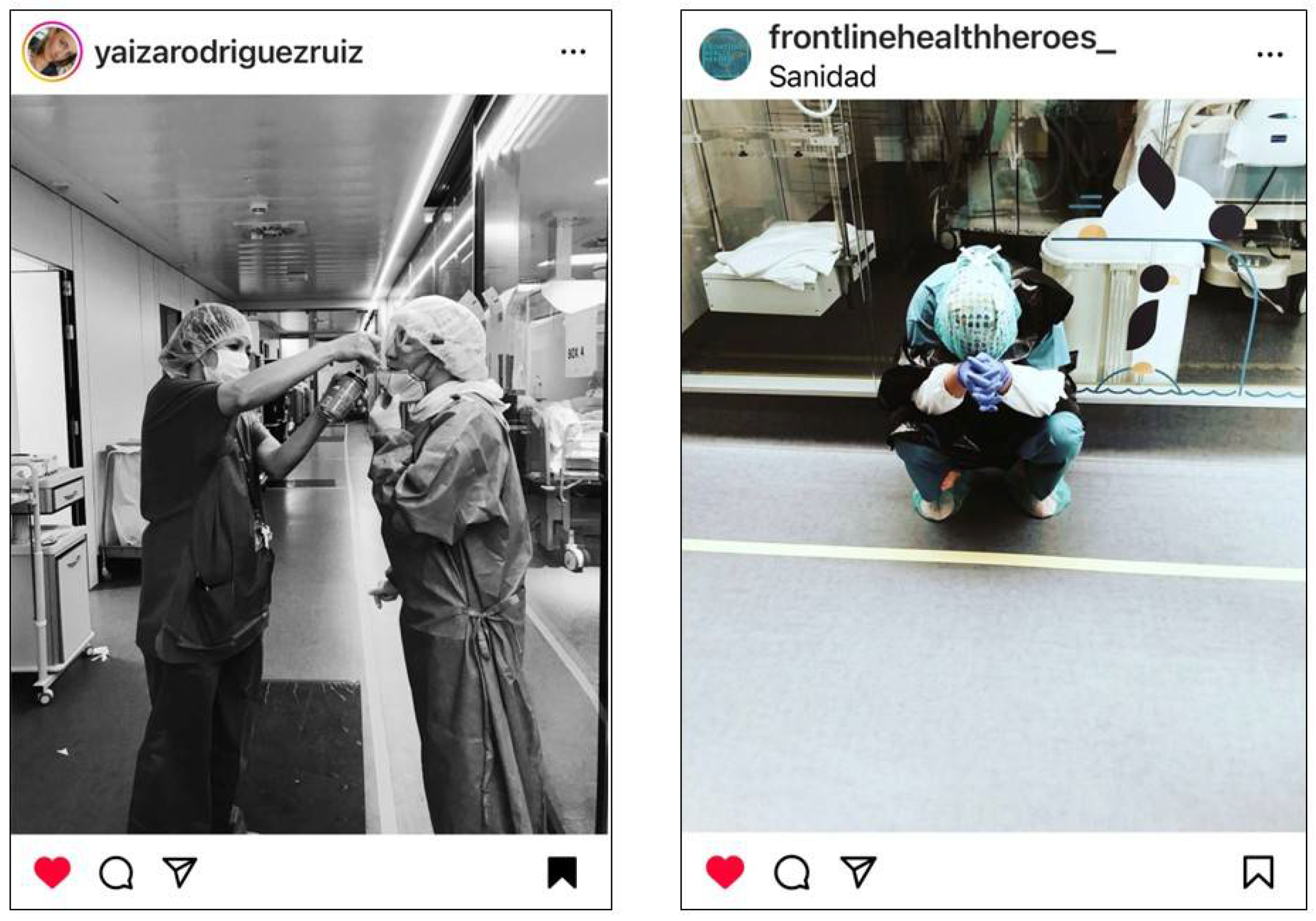

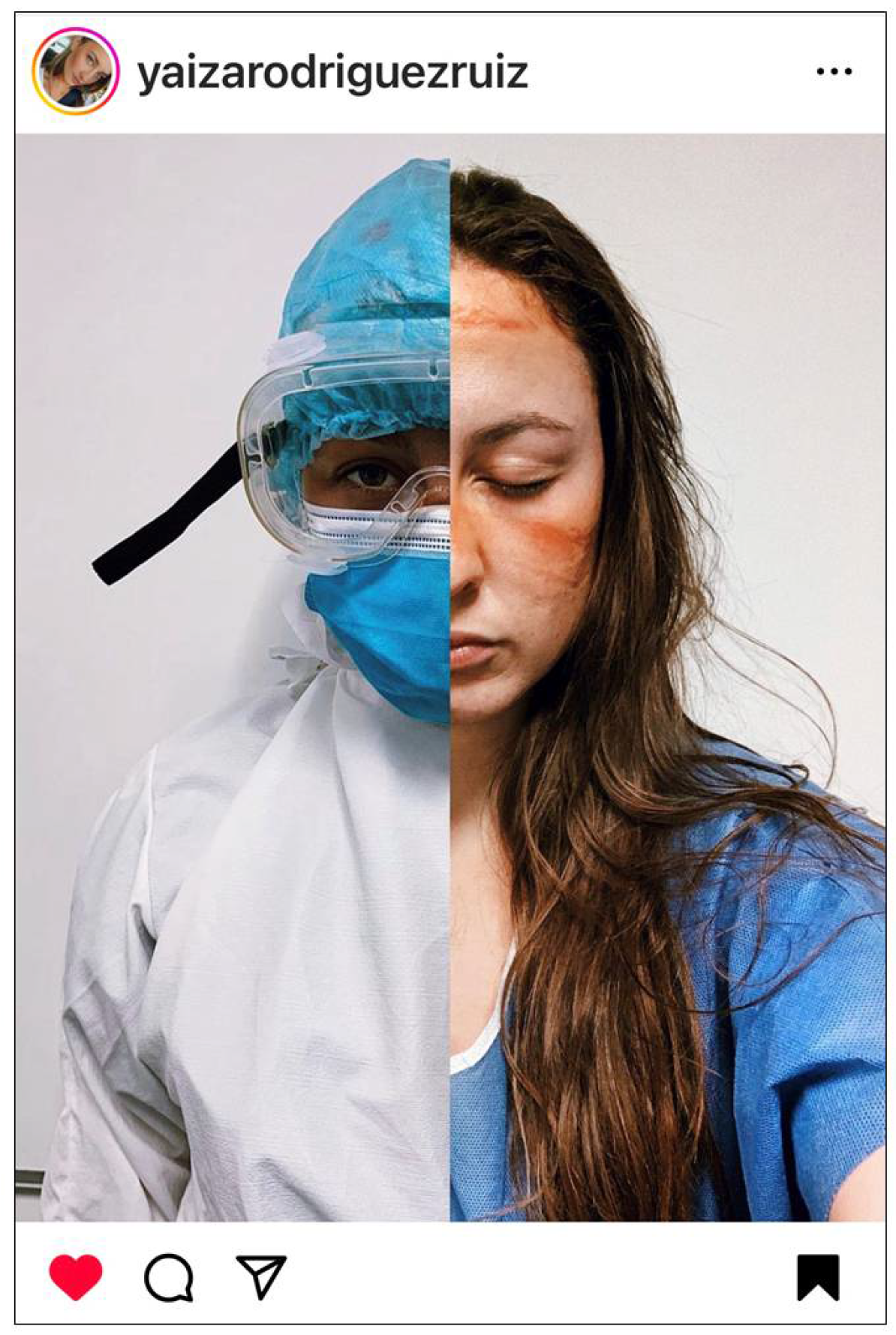

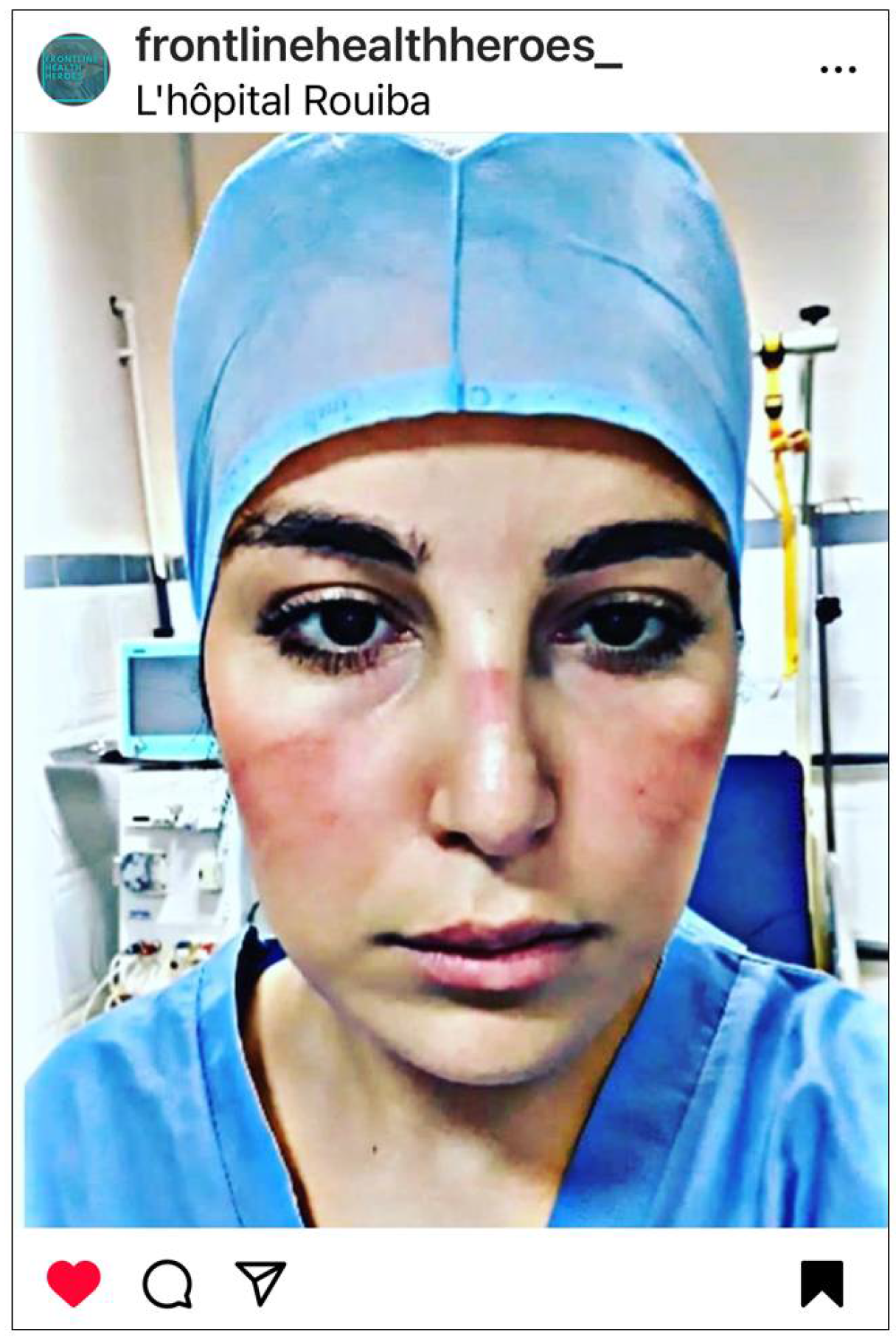

3.2. Faces Forever Marked by the Physical and Emotional Scars of COVID-19

“Back on day 2 when this nightmare began, all the health workers were struck by the injuries caused by the masks, glasses and other protections. Today day 36 of quarantine, those signs, wounds that have finally become scars that don’t matter, there are bigger scars in our hearts that no matter how much time passes, nothing, and no one can erase.…For every person we lose, a new scar opens. We will continue fighting so that those scars are smaller every day.”—Spain

“…we are giving it all and even more…we squeeze our teeth for physical and psychological pain, we cry secretly, But only 5 minutes, because then we have to be ready,…”—Italy

“without filters. This is my face after 12 hours of night, masks that cut your nose with every breath, every yawn.

A face marked not only by physical pain but also by the pain of the mind, by the strength you must have to be next to these people who have seen their lives change, …

Patients who have sadness and awareness of the disease on their faces. …”—Italy

3.3. The COVID-19 Battlefront: The Fight for Supplies and the Truth

“This is what you look like after wearing an N95 mask all day. We don’t have enough of anything. We need @SenSanders…”—USA

“…Being on the frontline working on a COVID19 unit in this national emergency, … We are taking this all on, doing the best we can with the supplies we’ve been given.

… Social media can be a blessing and a curse. The nurses and healthcare workers of this nation are trying to use it now to show just what we have been dealing with. We are not given the proper protective gear in order to protect ourselves while taking care of patients. Hospitals everywhere are running out of proper gear and supplies that are very much needed. Meaning healthcare employees are getting sick and contracting this deadly virus. The more employees that are out sick means the less employees we have to care for our patients. Many of my coworkers are out sick already and we haven’t even peaked yet. If you have access to getting #N95, respirators, surgical masks, face shields or ANY protective equipment please think about donating them to local hospitals to help protect us on the frontlines!

I urge you all to listen to what we have to say. We are seeing this all first hand…”—Canada

“This is a picture of my sore and swollen face after wearing mask all day in ICU. You can hardly recognise me. I worked 39 hours in ICU this weekend. This is the sacrifice we specialist nurses have to give. …

People are dying lonely deaths. Their family cannot visit the ICU. ICU beds are full. We are overwhelmingly busy. Please stay home unless it’s absolutely essential. Maintain social distance of at least 2 meters apart. Avoid overcrowded lift or transportation. Coronavirus is real. Save the NHS.”—England

3.4. Dire and Unprecedented PPE Shortage

“…. Every single time we go to our patient’s room, we put on a hair cover, N95 mask, goggles, face shield, a protective gown, and shoe covers. When we come out of the room we take it off. We do this over and over again numerous times in a 12 hour shift. This is my face after 6 hours.

Supplies are running low. We are running out of N95 masks and are given 1 for our entire 12 hour shift. We place it in a plastic or paper bag and keep reusing it again and again. We can only hope that we are protecting ourselves enough. I’m not going to paint a pretty picture. It’s a struggle. …”—USA

“Some numbers as my NYC assignment ends:

21 days, 12 hours a day, 20 patients a shift.

4 n95 masks.

Enough PPE to keep me safe(ish),…”—USA

“Dr. N [redacted for privacy] … collected donations of PPEs & gowns to give to his colleagues. Last week, this is N [redacted for privacy] about to intubate a patient, only wearing a patient’s gown because he couldn’t find PPE and the goggles leave these marks on his face.”—USA

“In the covid ICU, I get 1 mask and it goes into a brown paper bag at the end of every shift, and gets used for the next shift.

Same hair cover and shoe covers for the whole shift. In and out of the covid + patient rooms at least 3 or 4 times an hour.

Wipe down the construction like face shield and use it again next shift. There’s talk of cleaning and reusing some PPE after it’s already been used in a covid + patient room and the environment…”—USA

3.5. Pervasive Fear of Contracting COVID-19; Putting Colleagues and Family at Risk

“I am a nurse and I am facing this health emergency right now. I’m scared too, but not to go grocery shopping, I’m afraid to go to work. I’m scared because the mask might not fit my face well, or I may have accidentally touched myself with dirty gloves, or maybe the lenses don’t cover my eyes and something [sic COVID] might have passed. …”—Italy

“hot, muggy …. feeling of shortness of breath, drops of sweat falling from the face, a face that you feel melt under the FP3 mask, the plastic glasses, the visor, the cap; wrapped in a waterproof gown… “The patient must be intubated” … “is desaturating” … “… you run, you continue to sweat … you prepare the drug with two pairs of gloves that limit your habitual hand movements … you sweat again and after hours you have no respite but you can’t drink, you can’t rest, you can’t pee dressed like that … In all this, the anxiety of being able to contaminate by making the gestures that you used to do before, this anxiety is the background to every maneuver, every thought, every action that you have to perform, you must constantly repeat to yourself that I could no longer touch your head if the elastic for your hair it hurts, if your nose itches you can bear, if you have that unbearable rebreathing in your mask you continue to breathe in it again and again and finish your work … ”—Italy

“….An ER nurse in New York died today of COVID-19. He was in his 40s and had very mild asthma. That’s it. This is not just a tall tale, this is the real risk. I have to go into every patient’s room and in the back of my mind I think “this could be the patient that gets me sick… that kills me”.

“This could be the patient that gives me the virus I bring home to my children or asthmatic husband”.

This is my new reality.

But this is only the beginning. We haven’t even scratched the surface of the impact of what this illness is going to make on our country. And I’m scared.”—USA

“…we’re scared to eat lunch in such a contaminated workspace, for fear of dying amongst the lifeless bodies surrounding us. How ironic that would be. And that’s all you think about. All shift.

When am I gonna get it.

My coworkers know my code status right?

Will I be the cause of my husbands death?

Kids? …”—USA

“…When we finally get off work we can’t just come home and go to bed, we have to take every precaution to not spread this disease to our families,…”—USA

“…. I have not been able to see the people I love for fear that I might inadvertently give them this disease. …”—USA

“…#covid19 is different, so I’m much more scared for my family, scared to go to work, scared that I accidentally touch my face… afraid of bringing this virus home, afraid of contaminating my family! …”—Algeria

“While you’re bored and can’t stay at home, we are “falling” one by one as dominoes…”—Italy

3.6. Extreme Emotional and Physical Toll on Nurses and HCWs

“… I don’t sleep at all, my hair falls out and it has turned gray, I lose weight, I have tachycardia when I go to sleep, I want to cry all the time, my hands and

Iface hurt, I have hurt myself on my back from scratching due to stress and I have muscle contractures and pain all over my body, as well as an exhaustion that sometimes leaves me in bed unable to move and some problems that I will have to solve when this is over. And I’m not one of those who is worse…”—Spain

“I’ve been trying to think of captions that truly explain how I feel in regards to everything going on right now. And every time I think about it it’s just producing so much fucking anxiety, sadness, disappointment, fear… but instead we are drowning… each day comes with less support & more responsibility. The safety & security we had yesterday is gone the next day. We have no legal support to back us up as we continue to lose our rights as a nurse, as a human. We can’t escape the misery.

We go 13 hours at a time sweating in places we’ve never sweat before from the gowns & stale OR scrubs… faces & ears aching from the suffocating masks. Then we go & care for people who are dying alone, because there are no visitors allowed. The emotional burden truly rips at the caring heart of every nurse …”—USA

“… I don’t care how many hours I spend in a box [sic COVID ward], with my glasses and mask on, with the great PPE’s (irony) that they give us, being hot, overwhelmed, stressed because you get a ticket to the upac (one of the ICUs) and you know when you enter but never when you leave… this damn pandemic that is taking away our sleep, causing us anxiety, tachycardia, nerves, fear ….

And this is the result from 2:45 a.m. to 7:54 a.m., even second-skin dressings do nothing for me.”—Spain

“… Do not think that it is a walk [sic in the park] for us to face a shift of work in these conditions, physically and psychologically you come out almost destroyed, yet every day we are there, ready to fight again, for everyone, for Italy, for us and for you …”—Italy

“This is the face of someone who just spent 9 h in personal protective equipment moving critically ill Covid19 patients around London.

I feel broken—and we are only at the start. I am begging people, please please do social distancing and self isolation.”—England

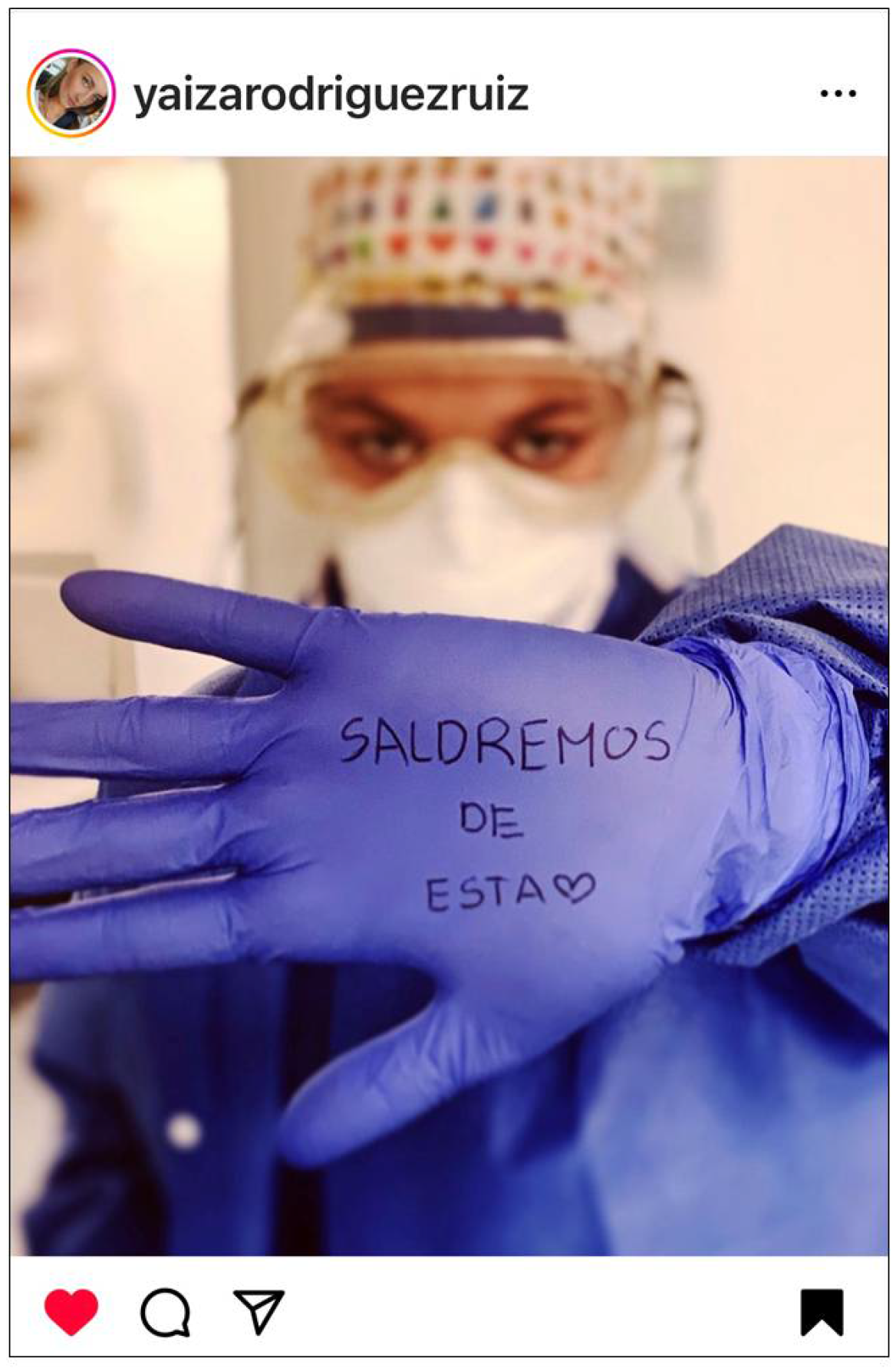

3.7. Creating a Collective Voice, the Shared COVID-19 Experience of Frontline Nurses and HCWs

“All of us health workers are very disappointed to see … If you saw what I’ve seen …Do you still remember that we risk our lives every day, we are exhausted, injured, with sleep problems, states of anxiety and stress? I think many people no longer even know why they go out to applaud at 8:00 p.m.”—Spain

“Mine and my colleagues faces are sore and we are run ragged. Mostly we are desperately trying to save lives. Please please #StayHomeSaveLives”—England

“…when it’s over, all the health personnel will go out into the street to claim and demand that public health is not to be played with and I hope that you will also go out with us and continue to applaud us, cheering us on. Because that’s when we’ll need you the most!”—Spain

“…I am psychologically tired, and as I am all my colleagues who have been in the same condition for weeks, but this won’t stop us from doing our job like we have always done. ….”—Italy

“…so proud of my NHS team for stepping up to face the challenge …”—England

“…we continue to go to work because we have to. Deep down we want to.

We want to help. It’s our calling. And I know that as nurses, nationally… globally… we will never stop doing what we are called to do. And we will die trying.”—USA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCW | Health care worker |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

References

- Buckley, B.; Wee, S.; Qin, A. China’s Doctors, Fighting the Coronavirus, Beg for Masks. The New York Times, 14 February 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/14/world/asia/china-coronavirus-doctors.html (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331498/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPCPPE_use-2020.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Law, T. Health Care Workers Around the World Are Sharing Bruised, Exhausted Selfies After Hard days Treating COVID-19 Patients. TIME, 22 March 2020. Available online: https://time.com/5807918/health-care-workersselfies-coronavirus-covid-19/ (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Fragkou, D.; Bilali, A.; Kaitelidou, D. Impact of personal protective equipment use on health care workers’ physical health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2021, 49, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemali, S.; Mari-Sáez, A.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Weishaar, H. Health care workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Health 2022, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragioti, E.; Li, H.; Tsitsas, G.; Lee, K.H.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Tsamakis, K.; Estradé, A.; Agorastos, A.; et al. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1935–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, L.; Quan-Haase, A. The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, A.; Ousey, K. Update to device-related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention. COVID-19, face masks and skin damage. J. Wound Care 2020, 29, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP). NPIAP Position Statements on Preventing Injury with N95 Masks. 2020. Available online: https://npiap.com/page/COVID-19Resources (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D.; Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Laestadius, L. Instagram. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.R.O. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hand, M. Visuality in social media: Researching images, circulations and practices. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, C. Online social networks: Concepts for data collection and analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, D. Digital ethnography: An examination of the use of new technologies for social research. In SAGE Internet Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instagram. About Us. Available online: https://about.instagram.com/about-us (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Weekly Operational Update on COVID-19-30 October 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-operational-update---30-october-2020 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- The Yellow House LLC. Covid-19 Supply Chain System Assessment Comprehensive Analysis; The Yellow House LLC: Arles, France, 2021; 269p, Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/cscs_comprehensive_slide_deck.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Latzko-Toth, G.; Bonneau, C.; Milette, M. Small data, thick data: Thickening strategies for trace-based social media research. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalancette, M.; Raynauld, V. The Power of Political Image: Justin Trudeau, Instagram, and Celebrity Politics. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 63, 888–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.; Dolbec, P.; Earkey, A. Netnographic analysis: Understanding culture through social media data. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAXQDA2022; VERBI GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EPUAP; NPIAP; PPPIA. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline: The International Guideline, 3rd ed.; EPUAP, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel: Lyon, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Song, S.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, A.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. The Prevalence, Characteristics, and Prevention Status of Skin Injury Caused by Personal Protective Equipment Among Medical Staff in Fighting COVID-19: A Multicenter, Cross-Sectional Study. Adv. Wound Care 2020, 9, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weilenmann, A.; Hillman, T. Selfies in the wild: Studying selfie photography as a local practice. Mob. Media Commun. 2020, 8, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfen, R. (Ed.) Looking Two Ways: Mapping the Social Scientific Study of Visual Culture. In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, K. Analysing Interviews. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldh, A.C.; Årestedt, L.; Berterö, C. Quotations in Qualitative Studies: Reflections on Constituents, Custom, and Purpose. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406920969268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.H.; Zhu, F.F.; Zeng, H.L.; Kong, Y.; Zhou, H.J. Influencing factors of medical device-related pressure ulcers in medical personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Pandemic Agreement. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA78/A78_R1-en.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ghebreyesus, T.A. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at media briefing—6 April 2023. In Proceedings of the Media Briefing, Geneva, Switzerland, 6 April 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-media-briefing-6-april-2023 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Andrews, L.; Dowrick, A.; Djellouli, N.; Fillmore, H.; Gonzalez, E.B.; Javadi, D.; Lewis-Jackson, S.; Manby, L.; Mitchinson, L.; et al. Perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Basanta, S.; Espremáns-Cidón, C.; Movilla-Fernández, M.J. Novice nurses’ transition to the clinical setting in the COVID-19 pandemic: A phenomenological hermeneutic study. Collegian 2022, 29, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Fragkou, D.; Bilali, A.; Kaitelidou, D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3286–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulaihah, S.; Harmayetty, H.; Kusumaningrum, T. Factors Related to Nurses’ Moral Distress in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review. Crit. Med. Surg. Nurs. J. 2022, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Botero-Tovar, N.; Herrera, M.A.; Kuhlmann, J.P.B.; Ortiz, F.; Ramírez, J.C.; Maldonado, L.F. Systematic review of experiences and perceptions of key actors and organisations at multiple levels within health systems internationally in responding to COVID-19. Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A.; Abbasi, S.; Mardani, A.; Maleki, M.; Vlaisavljevic, Z. Experiences of intensive care unit nurses working with COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1034624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peko, L.; Ovadia-Blechman, Z.; Hoffer, O.; Gefen, A. Physiological measurements of facial skin response under personal protective equipment. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 120, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellsson, G.; Clarke, P.; Gerdtham, U.G. Forgetting to remember or remembering to forget: A study of the recall period length in health care survey questions. J. Health Econ. 2014, 35, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla, S.; Mays, N.; Pleasant, A.; Walt, G. Describing the impact of health research: A Research Impact Framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catton, H.; Iro, E. How to reposition the nursing profession for a post-covid age. BMJ 2021, 373, n1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniol, M.; Kunjumen, T.; Nair, T.S.; Siyam, A.; Campbell, J.; Diallo, K. The global health workforce stock and distribution in 2020 and 2030: A threat to equity and ‘universal’ health coverage? BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Accelerating Action on the Global Health and Care Workforce by 2030. 2025, 6. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB156/B156_CONF14-en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Kavanagh, M.M.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Unnikrishnan, V.; Cometto, G.; Kane, C.; Friedman, E.A.; Srivatsan, V.; Gil Abinader, L.; Campbell, J.; Health & Care Worker Policy Lab. Correction: Laws for health and care worker protection and rights: A study of 182 countries. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0005057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solmos, S.; Eisenhauer, C.; Lally, R.; Cuddigan, J. “Without Filters” Nurse and Healthcare Worker Personal Protective Equipment Injuries and the COVID-19 Experience: An International Social Media Ethnographic Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111603

Solmos S, Eisenhauer C, Lally R, Cuddigan J. “Without Filters” Nurse and Healthcare Worker Personal Protective Equipment Injuries and the COVID-19 Experience: An International Social Media Ethnographic Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111603

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolmos, Susan, Christine Eisenhauer, Robin Lally, and Janet Cuddigan. 2025. "“Without Filters” Nurse and Healthcare Worker Personal Protective Equipment Injuries and the COVID-19 Experience: An International Social Media Ethnographic Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111603

APA StyleSolmos, S., Eisenhauer, C., Lally, R., & Cuddigan, J. (2025). “Without Filters” Nurse and Healthcare Worker Personal Protective Equipment Injuries and the COVID-19 Experience: An International Social Media Ethnographic Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111603