A Scoping Review of Preventive and Treatment Interventions of Parental Psychological Distress in the NICU in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

Interventions to Address Parental Psychological Distress

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Data Collection and Synthesis

3. Results

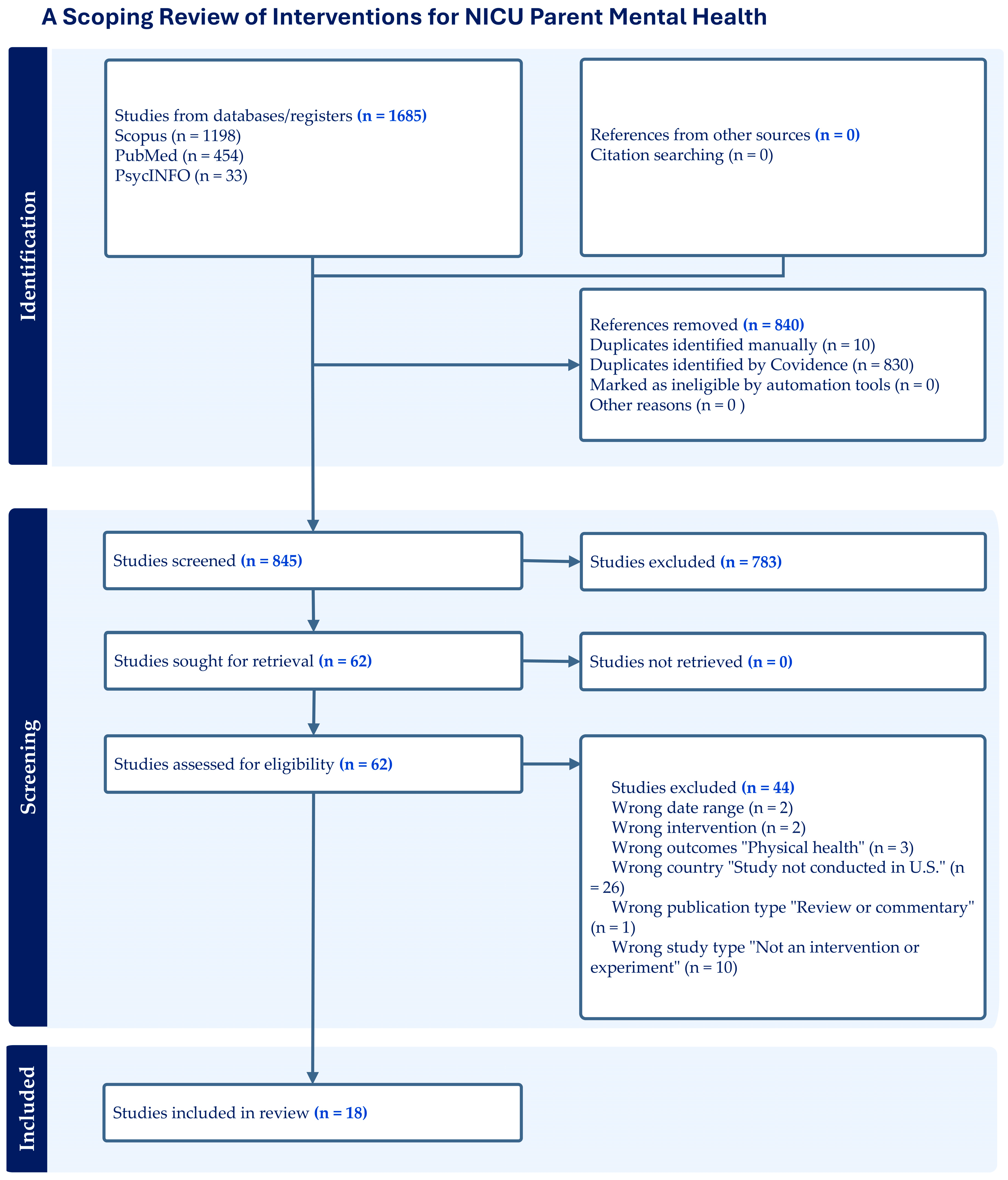

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Intervention Characteristics and Outcomes

3.3. Prevention Interventions

3.3.1. Psychotherapeutic

3.3.2. Educational–Behavioral Interventions

3.3.3. Educational

3.4. Treatment Interventions

3.4.1. Psychotherapeutic

3.4.2. Complementary/Alternative Medicine

3.5. Participant Engagement

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Implications for Future Studies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Unit |

| CBT | Cognitive behavioral therapy |

| COPE | Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment |

| mFICare | mobile-enhanced Family Integrated Care |

References

- Caporali, C.; Pisoni, C.; Gasparini, L.; Ballante, E.; Zecca, M.; Orcesi, S.; Provenzi, L. A global perspective on parental stress in the neonatal intensive care unit: A meta-analytic study. J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 1739–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouf, R.; Harrison, S.; Burton, H.A.L.; Gale, C.; Stein, A.; Franck, L.S.; Alderdice, F. Prevalence of anxiety and post-traumatic stress among the parents of babies admitted to neonatal units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 43, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, L.; Burke, K.; Cobham, V.E.; Kimball, H.; Foxcroft, K.; Callaway, L. The prevalence of PTSD of mothers and fathers of high-risk infants admitted to NICU: A systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 26, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maghaireh, D.F.; Abdullah, K.L.; Chan, C.M.; Piaw, C.Y.; Al Kawafha, M.M. Systematic review of qualitative studies exploring parental experiences in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2745–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewenstein, K. Parent psychological distress in the neonatal intensive care unit within the context of the social ecological model: A scoping review. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2018, 24, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomè, S.; Mansi, G.; Lambiase, C.V.; Barone, M.; Piro, V.; Pesce, M.; Sarnelli, G.; Raimondi, F.; Capasso, L. Impact of psychological distress and psychophysical wellbeing on posttraumatic symptoms in parents of preterm infants after NICU discharge. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, L.; Majiza, A.P.; Ely, C.S.; Singer, L.T. Psychological distress in the neonatal intensive care unit: A meta-review. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 96, 1510–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baía, I.; Amorim, M.; Silva, S.; de Freitas, C.; Alves, E. Parenting very preterm infants and stress in neonatal intensive care units. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, R.E.; Rogers, C.E.; Paul, R.A.; Gerstein, E.D. NICU hospitalization: Long-term implications on parenting and child behaviors. Curr. Treat. Options Pediatr. 2018, 4, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Thoyre, S.; Estrem, H.; Pados, B.F.; Knafl, G.J.; Brandon, D. Mothers’ psychological distress and feeding of their preterm infants. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2016, 41, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn, I.H.; Smith, L.; Smeby, N.A.; Kynoe, N.M.; Sandvik, L.; Bunch, E.H.; Lindemann, R. Effects of early mother–infant intervention on outcomes in mothers and moderately and late preterm infants at age 1 year: A randomized controlled trial. Infant Behav. Dev. 2012, 35, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, A.P.; Halemani, K.; Issac, A.; Thimmappa, L.; Dhiraaj, S.; Phil, R.K.M.; Mishra, P.; Upadhyaya, V.D. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among parents of neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2024, 67, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Sandhi, A.; Lee, G.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Kuo, S.-Y. Prevalence of and factors associated with postnatal depression and anxiety among parents of preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 322, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, D.S.; Baxt, C.; Evans, J.R. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2010, 17, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, T.; Cluxton-Keller, F.; Vullo, G.C.; Tandon, S.D.; Noazin, S. NICU-based interventions to reduce maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20161870–e20161883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, R.S.; Williams, S.E.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Rhine, W.; Horwitz, S.M.; Koopman, C.; Shaw, R.J. Brief cognitive–behavioral intervention for maternal depression and trauma in the neonatal intensive care unit: A pilot study. J. Trauma. Stress 2011, 24, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; Gay, C.L.; Hoffmann, T.J.; Kriz, R.M.; Bisgaard, R.; Cormier, D.M.; Joe, P.; Lothe, B.; Sun, Y. Maternal mental health after infant discharge: A quasi-experimental clinical trial of family integrated care versus family-centered care for preterm infants in U.S. NICUs. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holditch-Davis, D.; White-Traut, R.C.; Levy, J.A.; O’Shea, T.M.; Geraldo, V.; David, R.J. Maternally administered interventions for preterm infants in the NICU: Effects on maternal psychological distress and mother–infant relationship. Infant Behav. Dev. 2014, 37, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, M.G.; Halperin, M.S.; Austin, J.; Stark, R.I.; Hofer, M.A.; Hane, A.A.; Myers, M.M. Depression and anxiety symptoms of mothers of preterm infants are decreased at 4 months corrected age with family nurture intervention in the NICU. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2015, 19, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabnis, A.; Fojo, S.; Nayak, S.S.; Lopez, E.; Tarn, D.M.; Zeltzer, L. Reducing parental trauma and stress in neonatal intensive care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of hospital interventions. J. Perinatol. 2019, 39, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Family Database. PF2.1. Parental Leave Systems. February 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_1_Parental_leave_systems.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.Y.; Korale-Liyanage, S.; Jarde, A.; McDonald, S.D. Psychological or educational ehealth interventions on depression, anxiety or stress following preterm birth: A systematic review. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2021, 39, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiserud, T.; Piaggio, G.; Carroli, G.; Widmer, M.; Carvalho, J.; Jensen, L.N.; Abdel Aleem, H.; Talegawkar, S.A.; Benachi, A.; Diemert, A.; et al. The World Health Organization fetal growth charts: A multinational longitudinal study of ultrasound biometric measurements and estimated fetal weight. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.W.; Darlow, B.A. The changing face of neonatal intensive care for infants born extremely preterm (<28 weeks’ gestation). Semin. Perinatol. 2021, 45, 151476–151484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas Health Innovation 2023. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Page, M.J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Chou, R.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Li, T.; McDonald, S.; Stewart, L.A.; et al. The Prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. Prisma extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-SCR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.M.; Leibovitz, A.; Lilo, E.; Jo, B.; Debattista, A.; St., John, N.; Shaw, R.J. Does an intervention to reduce maternal anxiety, depression and trauma also improve mothers’ perceptions of their preterm infants’ vulnerability? Infant Ment. Health J. 2014, 36, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howland, L.C.; Jallo, N.; Connelly, C.D.; Pickler, R.H. Feasibility of a relaxation guided imagery intervention to reduce maternal stress in the NICU. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 46, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, K.L.; McClain, D.B.; Melnyk, B. Reducing anxiety among children born preterm and their young mothers. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2013, 38, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, N.M.; Mcintosh, J.J.; Flynn, K.E.; Szabo, A.; Ahamed, S.I.; Asan, O.; Hasan, M.K.; Basir, M.A. Multimedia tablet or paper handout to supplement counseling during preterm birth hospitalization: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100875–100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segre, L.S.; Chuffo-Siewert, R.; Brock, R.L.; O’Hara, M.W. Emotional distress in mothers of preterm hospitalized infants: A feasibility trial of nurse-delivered treatment. J. Perinatol. 2013, 33, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.J.; St John, N.; Lilo, E.A.; Jo, B.; Benitz, W.; Stevenson, D.K.; Horwitz, S.M. Prevention of traumatic stress in mothers with preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2013, 132, e886–e895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, R.J.; St John, N.; Lilo, E.; Jo, B.; Benitz, W. Prevention of traumatic stress in mothers of preterms: 6-month outcomes. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1612–e1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Feinberg, E.; Cabral, H.; Sauder, S.; Egbert, L.; Schainker, E.; Kamholz, K.; Hegel, M.; Beardslee, W. Problem-solving education to prevent depression among low-income mothers of preterm infants: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2011, 14, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Feinstein, N.F.; Alpert-Gillis, L.; Fairbanks, E.; Crean, H.F.; Sinkin, R.A.; Stone, P.W.; Small, L.; Tu, X.; Gross, S.J. Reducing premature infants’ length of stay and improving parents’ mental health outcomes with the creating opportunities for parent empowerment neonatal intensive care unit program: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1414–e1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, H.; Clements-Hickman, A.; Davies, C.C. Effect of a parent empowerment program on parental stress, satisfaction, and length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 35, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A.; Guillén, Ú.; Mackley, A.; Sturtz, W. Mindfulness training among parents with pre-term neonates in the neonatal intensive care unit: A pilot study. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019, 36, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouradian, L.E.; DeGrace, B.W.; Thompson, D.M. Art-based occupation group reduces parent anxiety in the neonatal intensive care unit: A mixed-methods study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 67, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petteys, A.R.; Adoumie, D. Mindfulness-based Neurodevelopmental Care: Impact on NICU parent stress and infant length of stay; A randomized controlled pilot study. Adv. Neonatal Care 2018, 18, E12–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdei, C.; Forde, M.; Cherkerzian, S.; Conley, M.S.; Liu, C.H.; Inder, T.E. ‘My Brigham Baby’ application: A pilot study using technology to enhance parent’s experience in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024, 41, e1135–e1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.N.; Gregory, M.L.; Warren, Z.E.; Weitlauf, A.S. Uptake and impact of journaling program on wellbeing of NICU parents. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 2057–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, L.; Maxwell, J.; Urbanosky, C. The needs of NICU fathers in their own words. Adv. Neonatal Care 2021, 22, e94–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefana, A.; Padovani, E.M.; Biban, P.; Lavelli, M. Fathers’ experiences with their preterm babies admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: A multi-method study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson-Salo, F.; Kuschel, C.A.; Kamlin, O.F.; Cuzzilla, R. A fathers’ group in NICU: Recognising and responding to paternal stress, utilising peer support. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 23, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanosky, C.; Merritt, L.; Maxwell, J. Fathers’ perceptions of the NICU experience. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2023, 29, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliouli, F.; Zaouche Gaudron, C. Healthcare professionals in a neonatal intensive care unit: Source of social support to fathers. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2018, 24, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affleck, G.; Tennen, H. The effect of newborn intensive care on parents’ psychological well-being. Child. Health Care 1991, 20, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeney, K.; Lohan, M.; Spence, D.; Parkes, J. Experiences of fathering a baby admitted to neonatal intensive care: A critical gender analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugill, K.; Letherby, G.; Reid, T.; Lavender, T. Experiences of fathers shortly after the birth of their preterm infants. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, M.J.; Tinero, J.A.; Rojas-Ashe, E.E. Psychosocial interventions and support programs for fathers of NICU infants—A comprehensive review. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 154, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ganduglia-Cazaban, C.; Chan, W.; Lee, M.; Goodman, D.C. Trends in neonatal intensive care unit admissions by race/ethnicity in the United States, 2008–2018. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, A.N.; Shaikh, H.; Oslin, E.; Gray, M.M.; Weiss, E.M. Race and ethnicity of infants enrolled in neonatal clinical trials. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2348882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, D.; Iacob, A.; Profit, J. Unequal care: Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care delivery. Semin. Perinatol. 2021, 45, 151411–151417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March of Dimes. Preterm Birth Rate by Race/Ethnicity: United States, 2020–2022 average. March of Dimes|PeriStats n.d. Available online: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=99&top=3&stop=63&lev=1&slev=1&obj=1 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Bourque, S.L.; Weikel, B.W.; Palau, M.A.; Greenfield, J.C.; Hall, A.; Klawetter, S.; Neu, M.; Scott, J.; Shah, P.; Roybal, K.L.; et al. The association of social factors and time spent in the NICU for mothers of very preterm infants. Hosp. Pediatr. 2021, 11, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Robson, K.; Bracht, M.; Cruz, M.; Lui, K.; Alvaro, R.; da Silva, O.; Monterrosa, L.; Narvey, M.; Ng, E.; et al. Effectiveness of family integrated care in neonatal intensive care units on infant and parent outcomes: A multicentre, multinational, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Prevention Studies Psychotherapeutic Educational–Behavioral Educational | 11 (61.1%) 4 (22.2%) 5 (27.8%) 2 (11.1) |

| Treatment Studies Psychotherapeutic Complementary/Alternative medicine | 7 (38.8%) 2 (11.1%) 5 (27.7%) |

| Geographical Setting Urban Multiple (Urban and rural) Unclear | 15 (83.3%) 1 (5.6%) 2 (11.1%) |

| Parent Race-Ethnicity American Indian Asian Black Hispanic/Latino (non-white) Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander Multi-racial White Not reported | 6 (0.5%) 51 (3.8%) 315 (23.8%) 190 (14.3%) 1 (0.1%) 5 (0.4%) 705 (53.1%) 53 (4.0%) |

| Author (s), Year | Participants | Design | Group Comparison | Psychological Distress Measures | Intervention Dose and Modality | Outcome (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention Studies (N = 11) | ||||||

| [43] | N = 50 40 birthing parents, 10 non-gestational parents | Pretest–posttest pilot | Experimental Digital app: My Brigham Baby | Stress—PSS: NICU Anxiety- GAD-7 | A digital smartphone app providing educational resources and support to parents of hospitalized infants, including access to medical records, educational materials, and tools for logging parenting activities. Participants were required to use the app at least once per week. | The PSS: NICU total scores exhibited a slight increase post-App rollout; however, this difference was not statistically significant. The GAD-7 mean total scores decreased from 8.6 ± 5.7 pre-App to 7.4 ± 5.6 post-App, but this change was non-significant. |

| [16] | N = 50 mothers Age M = 31.8 (sd = 4.9) Infant gestational age M = 31.3 weeks (sd = 2.8) | RCT | Experimental CBT Control NICU standard care | Depression—BDI-II Stress—SASRQ Trauma—DTS. | 3 CBT sessions lasting 45–55 min over the course of approximately 2 weeks during the infant’s hospital stay. | A trend toward reduced trauma and depressive symptoms in the CBT group, no statistically significant difference. |

| [17] | N = 178 mothers Age M = 30.8 (sd = 6.8) Infant gestational age M = 28.7 weeks (sd = 2.7) | Quasi-experiment | Experimental mFICare Control Usual FCC | Depression—EPDS Stress—PSS: NICU Trauma—PPQ. | The mFICare cohort received FCC, mhealth app, parent group education classes 2–5 times per week; participation in weekday rounds; peer mentorship. | No clinically significant differences between both interventions on PTSD or depression symptoms. mFICare may be more effective in preventing clinically significant PTSD symptoms than FCC alone for mothers experiencing higher levels of NICU related stress. |

| [18] | N = 240 mothers Age M = 26.6 (sd = 2.2) Infant gestational age ATVV: 27.0(2.8) weeks Kangaroo Care: 27.2 weeks (sd = 2.9) | RCT | Experimental Auditory–tactile–visual–vestibular (ATVV) and Kangaroo Care (KC) Control Attention control, discussed safely caring for preterm infant | Depression—CESD Stress—PSS: NICU Anxiety—STAI Trauma—PPQ. | ATVV Consisted of a 15 min session facilitated by a nurse. Mothers provided auditory, tactile, visual, and vestibular stimulation to their infants, starting with voice and gradually adding moderate stroking and eye contact as the infant became alert. KC Guided by a nurse, mothers held their infants in skin-to-skin contact for at least 15 min. | While neither intervention affected measures of psychological distress, those who engaged in KC had an increase in the rate of decline of distress in the first year. Parenting stress was lower for mothers who engaged in an intervention than those who did not. |

| [38] | N = 412 258 mothers, 154 fathers Age M = 31.5 (sd = 5.5) Infant gestational age M = 31.3 weeks (sd = 2.4) | RCT | Experimental Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) Control Attention control, provided standard information regarding hospital services and policies. | Depression—BDI-II Stress—PSS: NICU Anxiety—GAD7, STAI. | Trained nurses delivered a 4-phase educational–behavioral intervention, COPE program. (1) 2–4 days after infants’ admission; (2) 2–4 after first intervention; (3) 1–4 days before discharge; (4) 1 week after infant discharge. Utilized audiotape and materials. | Results indicated that mothers in the COPE program experienced significantly less stress in the NICU and less depression and anxiety at 2 months after infant discharge compared to the control group. |

| [39] | N = 49 parent pairs 49 mothers, 49 fathers Age M = 28.2 (sd = 0.06) Infant gestational age M = 31.9 weeks (sd = 2.1) | Quasi-experiment | Experimental COPE Control NICU Standard Care | Depression—EPDS Stress—PSS: NICU. | Trained nurses delivered a 4-phase educational–behavioral intervention, COPE program. (1) 2–4 days after infants’ admission; (2) 2–4 after first intervention; (3) 1–4 days before discharge; (4) 1 week after infant discharge. Utilized audiotape and materials. | The results of the study indicated that parents who participated in the COPE program reported significantly lower levels of overall parental stress compared to the comparison group. Specifically, there was a significant difference in the parental role subscale of the Parental Stress Scale: Neonatal (PSS) between the COPE parents and the comparison group. However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of postnatal depression scores or length of hospital stay. |

| [32] | N = 253 mothers Age M = 27.5 (sd = 4.7) Infant gestational age Mean not reported | RCT | Experimental COPE Control Attention control, provided standard information on hospital services, discharge, and immunizations. | Anxiety—STAI. | Trained nurses delivered a 4-phase educational–behavioral intervention, COPE program. (1) 2–4 days after infants’ admission; (2) 2–4 after first intervention; (3) 1–4 days before discharge; (4) 1 week after infant discharge. Utilized audiotape and materials. | Results suggests COPE intervention significantly predicted lower levels of (younger than 21) mothers’ anxiety levels at 2–4 days post intervention. |

| [33] | N = 59 mothers Age M = 30.9 (sd = 5.2) Infant gestational age M = 30 weeks (sd = 2.8) Multimedia M = 30 weeks (sd = 2.5) Paper | RCT | Experimental A multimedia tablet providing education regarding preterm birth and infant care to supplement verbal counseling Comparison Handout providing education regarding preterm birth and infant care | Anxiety—STAI. | Handout providing education regarding preterm birth and infant care. | Both the paper handout and multimedia tablet were equally and significantly effective at decreasing state anxiety. Participants were less likely to review all the educational materials on the tablet compared to the paper handout. |

| [35] | N = 105 mothers Age M = 32.4 (sd = 5.9) Infant gestational age M = 30.9 weeks (sd = 3.0) | RCT | Experimental Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT) Comparison One 45 min information session on NICU policies and parenting preterm infants. | Depression—BDI-II Stress—PSS: NICU, SASRQ Anxiety—BAI Trauma—DTS, TEQ. | Intervention included six sessions of a manualized TF-CBT and lasted 3 to 4 weeks with one or two 45–55 min sessions administered weekly. Sessions facilitated by trained therapists. | The intervention was effective in reducing symptoms of trauma and depression in mothers of preterm infants, with significant improvements in trauma symptoms and depression scores compared to an active comparison group. Although both groups showed a significant decline in anxiety scores without a significant difference between them. |

| [36] | N = 105 mothers Age M = 32.4 (sd = 5.9) Infant gestational age M = 30.9 weeks (sd = 3.0) | RCT | Experimental Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT) Comparison Usual care? One 45 min information session on NICU policies and parenting preterm infants. | Depression—BDI-II Stress—PSS: NICU, SASRQ Anxiety—BAI Trauma—DTS and TEQ. | Intervention included six sessions of a manualized TF-CBT and lasted 3 to 4 weeks with one or two 45–55 min sessions administered weekly. Sessions facilitated by trained therapists. | Mothers in the TF-CB group had significantly fewer symptoms anxiety (p = 0.001), depression (p = 0.002), and trauma (p =< 0.001), than mothers in the control group at 6 months. |

| [37] | N = 50 mothers Age M = 27.8 (sd = 7.0) Infant gestational age M = 28.5 weeks (sd = 3.5) | RCT | Experimental Solving Education (PSE) Comparison NICU Standard Care | Depression—QIDS Stress—PSS Trauma—MPSS-SR. | Manualized CBT consisting of 4 weekly individual sessions focused on problem-solving conducted at a location of the mother’s choice (i.e., hospital, home). Sessions facilitated by trained multi-disciplinary graduate students. | No statistically significant decrease in depression symptoms in mothers in the PSE group compared to the control group. |

| Treatment Studies (n = 7) | ||||||

| [30] | N = 105 mothers Age M = 32.3 (sd = 6.0) Infant gestational age M = 30.63 weeks (sd = 2.9) | RCT | Experimental CBT Control NICU standard care | Depression—BDI-II Stress—PSS: NICU, SASRQ Anxiety—BAI, Trauma—DTS. | Three 45–55 min CBT sessions over 2 weeks during the infant’s NICU stay. | Mothers in the CBT group showed a trend towards reducing trauma and depressive symptoms but did not show statistically significant results. |

| [31] | N = 20 mothers Age M = 27.3 (sd = 6.4) Infant gestational age M = 28 weeks (sd = 2.3) | Pretest–posttest feasibility | Experimental Relaxation guided imagery Control No control group | Depression—CES-D Stress—PSS Anxiety- STAI-AD. | Listening to a 20 min RGI recording at least once daily for 8 weeks. Participants were instructed to listen to one track for 2 weeks before they switched to the next track. During the last 2 weeks of study, participants could choose to listen to whichever track they most preferred. Short weekly phone call by an RA for participant to estimate how many times they had listened to the CD. | While the study found that the intervention was feasible and moderately helpful in reducing stress, the specific effects on depression and anxiety were not statistically significant. However, there were positive trends indicating lower perceived stress. |

| [40] | N = 28 26 mothers, 2 fathers Age M = 29.2 (sd = 6.8) Infant gestational age M = 29.2 weeks (sd = 2.6) | Feasibility | Experimental Mindfulness-based training session Control No control group | Stress—PSS: NICU. | A trained instructor facilitated individual sessions teaching parents mindfulness techniques, with the encouragement to practice these both at their infant’s bedside and away from the hospital. | Parents reported satisfaction with the intervention, however, there was not a significant difference in parental stress levels post-intervention. |

| [41] | N = 40 39 mothers, 1 father Age M = 26.4 (sd = 8.1) Infant gestational age M = 31.6 weeks (sd = 4.0) | Pretest–posttest | Experimental Art-based occupation group Control No control group | Anxiety—STAI. | Occupational therapist and art therapist facilitated 2-h art-based scrapbooking group sessions. An interdisciplinary team of professionals assisted with group. | Results indicated a significant reduction in state anxiety. Qualitative findings from the study suggested that parents found the scrapbooking activity to be a distraction from their worries, calming, relaxing, and enjoyable. It provided them with a sense of hope for the future beyond the NICU and connected them with other parents in similar situations, reducing their isolation and offering support. |

| [42] | N = 44 37 mothers, 7 fathers Age M = 30.2 (sd = 6.6) Infant gestational age M = 29.6 weeks (sd = 3.0) | RCT—Pilot | Experimental Mindfulness-based Neurodevelopmental Care Control NICU Standard Care | Stress—PSS: NICU. | Trained research professionals taught a one-on-one educational session for parents of preterm infants in the NICU, teaching mindfulness techniques and structured neurodevelopmental care training within 10 days of enrollment | No significant difference in between-group comparisons of stress, however, parents in the experimental group showed a significant decrease in stress scores from enrollment to discharge. |

| [44] | N = 97 67 mothers, 30 fathers Age M = 27.9 (sd = 5.0) Infant gestational age M = 35.6 weeks (sd = 3.8) | RCT | Experimental Journaling Control NICU Standard Care | Anxiety—HADS. | Participants journaled for a minimum of 2 weeks and a maximum of 4 weeks. Journal included blank pages as well as 10 prompts to guide parent reflection. | Parents in the intervention group showed a decrease in anxiety, although not statistically significant, while depression remained unchanged. Fathers who participated in the journaling program experienced a significant decrease in anxiety compared to mothers. |

| [34] | N = 23 mothers Age M = 27.9 (sd = 6.0) Infant gestational age M = 31.6 weeks (sd = 5.3) | Pre–posttest design Feasibility study | Experimental Group Listening sessions | Depression– EPDS Anxiety—BAI. | Six, 45–60 min listening visits over one-month period. | Significantly reduced depressive and anxiety symptoms, over half showing clinically meaningful improvement and high satisfaction with the intervention. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnett, K.A.I.; Sanders, A.; Kyser, R.; Babagoli, B.; Goyal, D.; Le, H.-N. A Scoping Review of Preventive and Treatment Interventions of Parental Psychological Distress in the NICU in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101592

Barnett KAI, Sanders A, Kyser R, Babagoli B, Goyal D, Le H-N. A Scoping Review of Preventive and Treatment Interventions of Parental Psychological Distress in the NICU in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101592

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnett, Kiara A. I., Ahnyia Sanders, Rebecca Kyser, Bahar Babagoli, Deepika Goyal, and Huynh-Nhu Le. 2025. "A Scoping Review of Preventive and Treatment Interventions of Parental Psychological Distress in the NICU in the United States" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101592

APA StyleBarnett, K. A. I., Sanders, A., Kyser, R., Babagoli, B., Goyal, D., & Le, H.-N. (2025). A Scoping Review of Preventive and Treatment Interventions of Parental Psychological Distress in the NICU in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101592