Abstract

Family caregivers provide most daily care for people living with chronic illness or frailty, yet they remain under-recognized in health and social care systems. To address this gap, we co-designed the Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education Program, which equips frontline providers with the competencies needed to lead caregiver-inclusive change. Guided by the Kirkpatrick-Barr Health Workforce Education Framework, we conducted a mixed methods interpretive description evaluation of learner satisfaction, knowledge and confidence gains, and self-reported behaviour change. Sixty-seven interdisciplinary participants completed three online modules. Quantitative results from pre/post surveys (Wilcoxon signed rank tests) showed significant improvements across all competencies (p < 0.001; large effect sizes) alongside high satisfaction (means 6.56–6.96/7). Qualitative findings revealed that 94% of participants applied program content within three months, and 61% implemented five or more distinct behaviour changes (e.g., collaborative care planning, system navigation support). The analysis illuminated how learners integrated caregiver-centred principles with change leadership strategies. Time constraints and staffing shortages emerged as key barriers. Our co-designed, theory-informed approach effectively bridged individual learning and system change, demonstrating the potential to transform caregiver inclusion practices when supported by organizational policies.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, health systems have widely adopted patient-centered care, which has improved diagnosis, treatment speed, and pathway coordination [1,2]. Yet family caregivers, who are the largest care workforce, remain largely invisible in health, social, and community care systems [3,4].

We define family caregivers (also called care partners or informal carers) as unpaid relatives, friends, neighbours, or others who provide practical, emotional, advocacy, and coordination support to a person of any age experiencing physical or mental health conditions, disability (including developmental or cognitive disability), substance-use or neurodevelopmental needs, injury, or age-related needs. “Family” includes both families of origin and families of choice, consistent with culturally diverse definitions of kin and support networks. This definition excludes paid staff, unless we are referring to double-duty caregivers (paid providers who also provide unpaid care at home) [5,6].

In Canada, approximately one in four adults—roughly 7.8 million people—take on this unpaid role [7,8]. Family caregivers provide between 75 and 90 percent of daily care for people living in community homes [9,10,11]. Even after a person moves into assisted living or long-term care, family caregivers continue to provide between 15 and 40 percent of direct care [12,13]. The conservative estimated value of these contributions exceeds 97 billion dollars annually [7,8]. However, escalating care demands, combined with limited preparation and recognition, have led to rising levels of caregiver distress [14].

National data show that both the length and intensity of caregiving have increased. For example, the proportion of caregivers providing ten or more hours of care per week rose from 26 percent in 2012 to 35 percent in 2018, while the proportion who reported that they had a choice about taking on caregiving fell from 57 percent to 42 percent [14]. Several factors explain these changes. Smaller family networks and higher participation of women in the workforce reduce the number of available unpaid caregivers. Hospital avoidance and early discharge policies shift complex care responsibilities into the home. Longer survival with chronic illness or disability extends caregiving duration. Family caregivers increasingly perform tasks once carried out by professionals, such as medication management, wound care, symptom management, and system navigation and advocacy. These demands are consistently associated with caregiver psychological distress, sleep disruption, financial strain, and reduced labour-force participation [15,16,17,18,19,20].

Unmet caregiver needs are not only personal hardships but also system-level risks. High caregiver strain is associated with increased emergency department visits, hospital readmissions, and earlier transitions to residential care for the person receiving care [7,8,9,10,11,12]. For caregivers themselves, the consequences include heightened risks of depression, injury, and income loss, with ripple effects across families and the wider economy [21,22,23]. Despite this, care plans rarely document caregivers’ contributions, seek their insights, or assess their capacity to continue caregiving [21,22]. A persistent assumption remains that “someone in the family will manage the plan.” As needs evolve and new providers join the care team, responsibilities are often shifted informally to caregivers—typically without documentation or assessment of their capacity and workload. This results in gaps between prescribed treatment and home-delivered care, and it widens the disconnect between professional intent and unpaid care realities [23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Although many frontline providers recognize caregiver strain, they face pressures that limit their ability to respond, including time constraints, staffing shortages, and misaligned incentives. Because caregiver support is rarely included in key performance indicators or reimbursement, task-shifting occurs without systematic assessment or documentation. This creates unmet needs for families and moral distress for clinicians [24,30,31,32,33].

To address these barriers, we previously co-designed and evaluated a competency-based Caregiver-Centered Care Education program, consisting of Foundational and Advanced modules (about seven hours of open access learning) [34,35,36]. These modules equip learners to: (1) recognize family caregivers as partners on the care team, (2) collaborate in assessment and care planning, (3) identify and respond to caregiver needs, risks, and preferences, and (4) connect families to health and community supports. The education emphasizes practical competencies and day-to-day behaviours, such as communication, identification, documentation, and referral.

The Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education program was developed as a subsequent step by the same co-design team. The earlier Foundational and Advanced education focuses on building caregiver-centered competencies. The Champions curriculum adds the dimensions of change leadership and implementation capability. It equips learners with strategies for embedding and spreading caregiver-centered care within teams and organizations, including structured approaches to change management such as Kotter’s model [37] the Prosci ADKAR Model (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) [38,39], and Plan Do Study Act [PDSA] cycles [40,41,42], which are widely used in quality improvement.

Health systems often rely on champions to spread evidence-based practices [43,44,45,46]. However, reviews show that most champion models depend on a single site-nominated individual, provide brief and information-heavy training, and have limited theoretical grounding or mentorship. Effectiveness often depends on individual motivation rather than systematic preparation [47,48]. We sought to address these gaps by developing the Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education, a competency-based, evidence-informed, and theoretically grounded program aligned with best practices in healthcare workforce education [38,49,50,51]. Our goal was to prepare learners to reshape mindsets, practices, and organizational culture by equipping them to lead caregiver-inclusive change.

This paper outlines the design of the Champions Education and evaluates its impact using the first three levels of the Kirkpatrick-Barr Health Workforce Education Framework: learner reaction, knowledge and attitude change, and self-reported behaviour [52,53].

1.1. Caregiver-Centred Care Champions Education

The Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education program trains both frontline staff and family caregivers to lead measurable improvements in the recognition, inclusion, and support of family caregivers across hospitals, primary care, community agencies, and long-term care. Champions model caregiver-centered practice, collaborate with families on care planning, share knowledge through mentoring and in-service teaching, and lead structured change initiatives to embed and sustain these practices.

1.1.1. Alignment with Best-Practice Education Design

The curriculum reflects best practices in healthcare workforce education. It was designed using modular micro-learning, authentic scenarios, explicit learning objectives, opportunities for reflection and feedback, and options for asynchronous and facilitated delivery. These design features were selected to maximize accessibility, relevance, and transfer of learning into practice [49,50,51].

1.1.2. Mechanism for System Change

The program positions Champions as boundary-spanning change agents. Champions apply a train-the-trainer model, use small tests of change through Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles in team huddles and rounds, and implement workflow tools such as caregiver identification and assessment prompts, documentation cues, and electronic medical record flags [40,41,42]. These strategies “hard-wire” caregiver-centered practices at the local level. Spread across organizations is supported by a community of practice and by alignment with leadership priorities, which help to sustain momentum and normalize new behaviours.

1.1.3. Participant Recruitment and Enrolment

We recruited participants between August 1 and September 15, 2023, through email invitations, co-design networks, and targeted social media. Eligible learners included experienced family caregivers, frontline health and social service providers, educators, and leaders across care settings. We specifically targeted individuals who had completed the foundational and advanced education and demonstrated motivation, confidence in their ability to influence others, digital fluency, and local leadership potential.

1.1.4. Recognition and Credentialing

Graduates of the program receive a Continuing Competency Certificate in Caregiver-Centered Care. Accreditation with professional colleges is in progress. The learning outcomes are aligned with the six domains of the Caregiver-Centered Care Competency Framework Caregiver-Centred Care Competency Framework [36] and stretched beyond based on appreciative inquiry [54,55], quality improvement [56,57], and change management [37,38].

1.2. Theoretical and Evidence Base

1.2.1. Co-Design as a Foundational Philosophy

We grounded the program in the principle that those who deliver, receive, and rely on care should have a voice in shaping the systems that support them [58,59,60,61]. Family caregivers, providers, educators, and leaders all participated as co-designers and ultimately as Champions. A 146-member co-design team collaborated to create the curriculum, bringing together what we describe as “voices of intent, capability, experience, and design” [62]. This approach ensured both academic rigor and practical relevance.

Between August 2022 and September 2023, we held six virtual co-design meetings. Breakout discussions were recorded and transcribed to capture detail. From September to December 2023, fifty participants met virtually three additional times to develop and test program content and tools. Opportunities for input were also offered through email and one-to-one conversations, which allowed for flexible participation.

1.2.2. Rights- and Values-Based Orientation

The program was designed within a rights- and values-based framework, rooted in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [63] and principles of person-centered care ethics [64,65]. We operationalized five values through concrete learning tasks:

- Respect: documenting caregiver preferences.

- Meaningful participation: involving caregivers as co-facilitators and case examples.

- Equity: ensuring diverse scenarios, plain language, and asynchronous access.

- Organizational accountability: embedding caregiver recognition through electronic medical record prompts and audit-and-feedback tools.

- Empowerment: encouraging learners to set specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals [66,67], use Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles [40,41,42], and participate in peer coaching.

Pedagogically, we applied sociocultural and transformative adult learning principles as well as constructivist design [68,69,70,71]. Instructional methods included caregiver video vignettes, guided reflection and feedback, and authentic workplace problems that led to usable tools or practices. Appreciative inquiry methods encouraged learners to identify and build on local strengths [54,55].

1.3. Curriculum and Learning Process

1.3.1. Structure of the Learning Modules

The program consisted of three asynchronous online modules, each lasting 45 to 60 min, with optional live facilitated discussions to enhance reflection and peer exchange. The modules were:

- Module 1: Inspiring Change—focused on leadership self-awareness and creating a compelling caregiver-centered vision.

- Module 2: Leading Change—focused on stakeholder mapping, building team capacity, and transforming resistance into collaboration.

- Module 3: Managing Change—focused on adaptation cycles, outcome metrics, and sustainability planning.

1.3.2. Instructional Strategies

We used a variety of instructional strategies to maximize engagement and transfer into practice. These included caregiver video vignettes, empathy mapping, role-play, and guided reflection exercises. Learners were also provided with downloadable tools to support practice change in their own settings.

1.3.3. Outputs and Practical Application

By the end of the program, participants produced a concrete change management action plan that they could apply in their workplace. This included a vision statement, a baseline assessment of current practice, a chosen micro-practice for improvement, a process measure, and a sustainment plan.

1.3.4. Community of Practice

After completing the modules, participants were invited to join a community of practice. These groups provided opportunities for peer mentorship, problem-solving, and sharing of strategies to address barriers. They also created a forum for sustaining motivation and extending learning beyond the initial course.

The curriculum was organized into three modules: Inspiring Change, Leading Change, and Managing Change. Together, these modules guided learners through a six-stage cycle: Dream, Discover, Determine, Design, Develop, and Drive Forward.

1.3.5. Learners Produced Practical Outputs at Each Stage, Including:

- a one-sentence vision and “why now” statement,

- a baseline scan and stakeholder map,

- the selection of one micro-practice (for example, identifying caregivers at the first point of contact),

- a simple tool (such as an electronic medical record prompt or pocket card),

- a one-shift Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycle [40,41,42], and

- a sustainment plan using the Prosci ADKAR Model (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) [38,39].

This six-stage cycle was reinforced by leadership strategies adapted from Kotter [37], Prosci’s Model for Improvement [38] with its Plan Do Study Act cycles [40,41,42]. Learners also had ongoing access to an online resource hub to support implementation and sustainment.

1.4. Intended Contribution

1.4.1. Integration of Theory and Practice

The Champions Education program was designed to integrate theory, co-designed curriculum, and an implementation “practice bundle.” This combination enables frontline staff and leaders to embed small but meaningful changes that make caregiver partnership visible and routine.

1.4.2. The Practice Bundle

The bundle included practical templates and scripts for caregiver identification and assessment, shared decision-making, and teach-back communication. It also included sample wording for electronic medical record documentation and a set of quality improvement tools, such as stakeholder maps, driver diagrams, SMART goal planners, and Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycle run charts [40,41,42].

1.4.3. Adaptation to Local Contexts

These tools were designed to be adapted and tested in local workflows. Learners used them to run small-scale tests of change and to refine practices based on real-world conditions. This approach encouraged ownership, contextual fit, and sustainability.

1.4.4. Program Summary and Supplementary Materials

A concise summary of the program was provided earlier in this paper, and full operational details are included in Supplementary Materials S1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Theoretical Framing

We used a mixed methods interpretive description design to evaluate the program. Interpretive description is an approach well suited to applied health disciplines because it generates insights that directly inform practice [72,73,74].

The Kirkpatrick-Barr Health Workforce Education Framework [72,73,74] guided our evaluation. We assessed outcomes across three levels:

- Learner satisfaction and engagement,

- Changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes, and

- Self-reported behaviour change.

We obtained ethical approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (Pro00138770; Pro00109366). We also followed the Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study (GREET) reporting guidelines [75].

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Educational Context

We recruited participants between 1 August and 15 September 2023. Recruitment was conducted through invitations to individuals who had completed the Foundational and Advanced caregiver-centered care education, through outreach to members of the co-design team, and through targeted social media posts.

To be eligible, participants had to:

- Be a health, social, or community care provider or leader, or an experienced family caregiver,

- Have completed the Foundational and Advanced modules (or committed to completing them before the first session), and

- Have access to an internet-enabled device.

Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided electronic consent.

A total of 67 individuals enrolled. Of these, 62 participants (92.5 percent) completed the full program, and 49 completed the three-month follow-up survey.

The program curriculum consisted of three asynchronous online modules (each 45–60 min) with optional live discussions. Learners produced a vision statement, a baseline scan and stakeholder map, the selection of one micro-practice for improvement, a local tool such as an electronic medical record prompt, a one-shift Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycle with a process measure, and a sustainment plan. Additional details are provided in Supplementary Materials S1.

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

We developed all evaluation instruments using a theory-driven approach. Each item was mapped to the Caregiver-Centered Care Competency Framework [36], to change leadership theory (Kotter; ADKAR) [37,38], and to contemporary education evaluation principles [76]. Our design was also informed by rights- and values-based adult learning orientations [68,70,77].

Survey stems were adapted from validated items used in previous evaluations of caregiver-centered care education [35,78,79]. We refined the instruments through co-design input and pilot testing. Surveys were administered electronically through Google Forms, and data were exported to Excel.

- Level 1 (Reaction and Satisfaction, immediate post-course): Five Likert-scale items and one open-ended question captured learner engagement, perceived relevance, perceived usefulness, strengths, areas for improvement, and likelihood of recommending the course.

- Level 2 (Knowledge, Skills, and Confidence, pre- and post-course): A nine-item Caregiver Champions Knowledge and Confidence Scale (7-point Likert; Cronbach’s α = 0.82–0.91). Pre and post surveys were linked anonymously by participant-chosen codes.

- Level 3 (Behaviour Change, three-month follow-up): The same scale was re-administered, along with additional items assessing enactment of caregiver-centered practices, progress on SMART goals, and perceived barriers and enablers.

Full versions of the instruments are provided in Supplementary Materials S2.

2.4. Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis: We summarized demographics and satisfaction using descriptive statistics. Paired-sample t-tests were used to assess pre- and post-program changes, with Cohen’s d used to estimate effect sizes.

Qualitative analysis: We conducted inductive content analysis [80,81] of open-ended survey responses at all three Kirkpatrick-Barr levels. Two researchers independently reviewed the data, coded transcripts using NVivo, and grouped codes into categories. We then refined these into themes aligned with the program modules and Kirkpatrick-Barr levels. We enhanced credibility through dual coding, iterative discussions, and interpretive consensus.

Finally, we integrated the qualitative findings with the quantitative results to provide a fuller understanding of how learners applied caregiver-centered care principles and leadership strategies in practice.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

We recruited 67 participants from diverse professional backgrounds: nurses (n = 29, 43%), social workers (n = 7, 10%), recreation therapists (n = 6, 9%), occupational therapists (n = 5, 7%), caregivers (n = 5, 7%), physiotherapists (n = 3, 4%), dietitians (n = 2, 3%), and others (e.g., youth worker, psychologist, SLP, primary care assistant, healthcare aide, physiotherapy assistant, kinesiologist, not-for-profit leader (n = 2), business owner; each 1–3%). Settings included home care (n = 18, 27%), acute care (n = 16, 24%), community services (n = 15, 22%), long-term care (n = 10, 15%), primary care (n = 6, 9%), and palliative care (n = 2, 3%).

The majority of participants identified as female, with only six participants (9%) identifying as male. Most were mid-career professionals: 26 were aged 45–54 (39%), and 23 were aged 35–44 (34%). Younger participants included eight aged 26–34 (12%) and one aged 21–25 (1%), while older participants included six aged 55–64 (9%) and three aged 65 or older (4%). No participants were aged 20 or younger. Completion rate was 92.5% (62/67); 49 (73.1%) completed the 3-month survey.

3.2. Results of the Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education

Participants reported high satisfaction, meaningful knowledge gains, and substantial changes in attitudes, behaviours, and clinical practice. Qualitative findings across survey and interview data also demonstrated how participants were applying the core competencies in their day-to-day work and internalizing the leadership lessons embedded in the Champions modules.

3.2.1. High Satisfaction and Relevance (Kirkpatrick-Barr Level 1)

Mean satisfaction ratings ranged 6.56–6.96/7 (median/mode = 7). Learners valued clarity, relevance, and asynchronous delivery. Participants described the course as energizing and validating, with one stating, “It has reinvigorated my energy and increased my skill set in making change.” Another reflected, “It was great to connect with others who have a vested interest in this type of work… It made me feel less alone or isolated in this journey”.

Participants who attended the facilitated learning sessions valued hearing from others across sectors, which helped them reflect on their own practice and envision systemic change: “I have loved learning from others around shared visions and different perspectives and learning needs—seeing how they are looking to make practice changes”.

3.2.2. Significant Increases in Knowledge and Confidence (Kirkpatrick-Barr Level 2)

Distribution checks indicated non-normality; Wilcoxon tests showed significant increases in total Knowledge and Confidence scores (Z = −6.21, p < 0.001; r = 0.80). All items improved (p ≤ 0.001; r = 0.43–0.71), with the largest shifts for implementation planning and overcoming barriers. See Table 1 Wilcoxon Rank Tests Pre-Post Education Parametric corroboration. Paired t-tests showed the same pattern (all t(60) |−3.8|–|7.5|, p < 0.001), with large Cohen’s d across items (0.65–0.96; largest for question 9 d = 0.96; smallest for question 5 d = 0.65). See Table S1 Paired Samples t-tests with Cohen’s effect sizes.

Table 1.

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

In the qualitative data, the strongest reported improvement related to reflective practice:

“It reminded me to listen closely and ensure I paraphrased the need. It helped me recognize strengths and encouraged me to stretch my thinking about what I or others can do.”

Others noted the practical ways the course enhanced their confidence in working within teams:

“I work in the community setting, so the course gave more concrete examples of how different healthcare professionals could realistically be actively supporting caregivers.”

Several participants began to recognize how small shifts in communication could translate into big differences in caregiver trust and engagement. As one noted, “I now ask caregivers what they need, rather than assuming”. Three participants reported they had been caregiver champions for years, so while they did not think it added to their knowledge and confidence, welcomed the course to develop more champions, “Not a lot of new learning with my 30 years of experience, but I welcome the course for the opportunity for new colleagues to carry the torch”.

3.2.3. Behavioural Change and Application in Practice (Kirkpatrick-Barr Level 3)

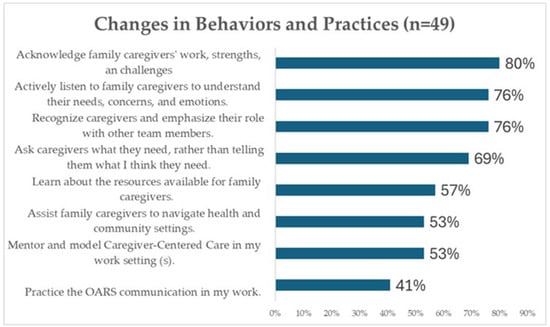

Three to six months after completing the Caregiver-Centered Care (CCC) Champions Education Program, 46 of 49 (93.8%) respondents reported making changes in their caregiving-related behaviours and clinical practices. While 38.7% reported making between one and four changes, the majority—61.3%—had implemented five to eight distinct changes. This suggests that the program had a strong impact not just on learners’ knowledge and attitudes, but on their day-to-day practice.

These self-reported behaviour changes strongly aligned with the four Caregiver-Centered Care Core Competencies:

- 80% began to more intentionally acknowledge caregivers’ contributions and challenges.

- 76% recognized caregivers as essential members of the care team and emphasized this with colleagues.

- 76% actively listened to caregivers to better understand their needs and emotions.

- 69% moved from prescriptive approaches to more collaborative care planning—asking caregivers what support they required rather than assuming. See Figure 1 for Changes in Behaviors and Practices.

Figure 1. Changes in Behaviours and Practices.

Figure 1. Changes in Behaviours and Practices.

These quantitative results were further supported by qualitative reflections from learners, which illustrated how the CCC core competencies and Champions Education modules were integrated into practice. Learners described how the program reinforced caregiver-inclusive values, inspired team discussions, and catalyzed new roles or programs. For example:

“I became more like a listener who listens to families’ needs and their expectations.”

“I now step back and ask what the caregiver thinks they may need instead of overwhelming them with information.”

“I created a family/caregiver resource document and check in with them to ensure they know we care about them and are here to support them.”

These changes reflect participants’ deepened commitment to the core CCC competencies:

- Recognizing caregivers as team members

- Partnering in care planning

- Assessing and supporting caregiver needs

- Guiding caregivers through health and community systems

Although the Champions Education primarily focused on change leadership and system improvement, many learners reported re-engaging with foundational caregiver-centered principles through the program’s reflective and action-oriented components. This included structured planning activities, Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles, and personal vision development, which helped participants internalize and reapply the core competencies in practical ways.

The integration of both CCC content and change leadership skills led participants not only to implement changes themselves, but to influence their teams and work settings. These included new documentation practices, peer education efforts, and caregiver-inclusive initiatives. Table 2 below summarizes key themes and exemplar quotes reflecting both CCC competencies and the three modules of the Champions Education.

Table 2.

Exemplar quotes mapped to competencies and modules.

3.2.4. Enablers and Barriers to Implementation

Enablers: time to interact with caregivers (78.6%), positive relationships (76.2%), colleague support (50.0%), leadership support (40.5%).

Barriers: lack of time (51.2%), competing demands (46.5%), staffing shortages (41.9%), leadership resistance (16.3%).

Time was both enabler and barrier. Team/leadership support influenced embedding practices in workflows; systemic constraints underscored the need for policy and workflow alignment.

4. Discussion

Our mixed methods evaluation indicates that the Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education program produced meaningful gains in knowledge, confidence, and self-reported behaviour related to caregiver engagement and leading change. Although the Caregiver-Centered Care Competency Framework [36] underpinned the program, the instructional focus extended beyond competency acquisition to emphasize change leadership and implementation. Large and consistent pre-post improvements suggest that participants developed stronger perceived capacity to lead change, which conceptually aligns with constructs in the Theory of Planned Behaviour [80,81].

4.1. Positioning Relative to Prior Programs

These findings build on earlier evaluations of the Caregiver-Centered Care Education Foundational and Advanced modules, which emphasized awareness and practice skills [34,35]. They also align with broader workforce education programs where features such as modular design, reflective practice, and authentic scenarios support knowledge transfer [49,50,51]. The Champions curriculum extends this literature by integrating change leadership and quality improvement approaches, including Kotter’s model, the Prosci ADKAR Model (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement), and Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles [37,38,39,40,41,42]. In addition, the inclusion of experienced family caregivers as co-learners addressed limitations of traditional “champion” programs, which often rely on brief, information-heavy training with little theoretical grounding or mentorship [47].

4.2. Why Leadership-Oriented Approaches Matter Now

Family caregivers deliver the majority of daily care, between 75 and 90 percent in community settings [9,10,11], yet their roles are often overlooked in health, social, and community care planning and documentation [82,83,84]. As health systems shift more complexity into the home, responsibilities are transferred to caregivers without assessment of their capacity [29,85,86], which contributes to caregiver distress and system inefficiencies [16,17]. At the same time, in our patient-focused systems, clinicians face time pressures, staffing shortages, and incentives that are not aligned with caregiver support [29,87].

Preparing staff to lead practical, unit-level change is one promising way to narrow the gap between system intent and caregiver experience. In our program, learners created unit-specific tools, facilitated short in-service sessions, and applied Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles to test practices such as caregiver identification at the first point of contact. These activities cultivated shared ownership, flattened hierarchies, and engaged colleagues in collaborative practice. Such mechanisms are consistent with literature on co-design and knowledge mobilization [29,85,88,89].

4.3. Barriers, Transfer Climate, and Sustainment

Our evaluation highlighted enduring challenges. Participants reported that lack of time, competing priorities, and staffing shortages constrained their ability to sustain new practices. These factors reflect the transfer climate, which strongly shapes whether learning is adopted and maintained. Research suggests that lasting change requires visible leadership endorsement, shared team norms, protected time, and straightforward ways to measure and communicate progress [40,41,45,56,88,89].

The Champions model addressed some of these conditions by combining train-the-trainer approaches, small tests of change within team huddles, workflow reminders such as electronic prompts, and peer-to-peer support through communities of practice. Together with leadership alignment, these elements appear to increase feasibility in complex settings [40,41,45,56,88,89].

4.4. Implications for Systems Change

Our findings point to practical steps that organizations can take to embed caregiver-centered care at scale. These include:

- Integrating caregiver identification and assessment templates into workflows, including electronic medical records.

- Normalizing collaborative care planning as standard practice [90,91].

- Using brief communication techniques such as teach-back [92] and goal-setting [66] within routine encounters.

- Resourcing communities of practice so that Champions can mentor peers and address barriers as they arise [93,94].

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include a theory-informed design guided by the Kirkpatrick-Barr Health Workforce Education Framework, co-design with a large and diverse stakeholder group, the use of mixed methods, and high program completion rates. Because learners in this cohort had previously completed the Foundational and Advanced Caregiver-Centered Care Education, they may have had a positivity bias toward caregiver-inclusive practice. Limitations include reliance on self-reported outcomes, a modest sample size, and contextual specificity that may limit generalizability. Participants were predominantly health and social care professionals, with a smaller subset of experienced family caregivers. We did not directly measure outcomes for family caregivers receiving support; findings reflect learner perceptions and self-reports at follow-up. Attendance at optional live sessions was not systematically tracked.

4.6. Recommendations

Based on our findings, we recommend the following actions:

- Scale and spread the program: Extend the Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education to additional care settings and regions, prioritizing acute care, emergency departments, and rehabilitation services where caregiver visibility remains low [21,22,23].

- Strengthen leadership engagement: Embed expectations for caregiver-centered practice in policy frameworks, job descriptions, performance metrics, and accreditation standards [95].

- Support communities of practice: Provide ongoing opportunities for Champions to sustain momentum, share strategies, and access peer mentorship through structured follow-up or regional learning hubs [21,22,23].

- Reinforce behaviours through structures: Create organizational tools and policies that formally recognize caregiver roles, such as caregiver assessment templates and documentation prompts [95].

- Address implementation barriers: Integrate caregiver-centered care into existing workflows and team models, and advocate for protected time to support caregiver engagement activities [65,66,95].

- Normalize caregiver education: Include caregiver-centered education in the foundational training of health, social care, and community trainees so that partnership with caregivers becomes standard practice [29,50,57,96].

- Expand evaluation metrics: Move beyond learner self-report to assess caregiver outcomes, team function, and system-level measures such as documentation reliability in electronic medical records [29,85,87].

4.7. Implications for Practice

For interprofessional teams, caregiver partnership can be advanced by identifying and documenting the caregiver at first contact, inviting caregivers into care planning and bedside handovers, and applying communication techniques such as teach-back and goal-setting during routine workflows. Unit-based Champions can coach peers and run Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles to reinforce these practices [40,41,49,50,51,56,95,97]. Electronic prompts in medical records and structured team huddles can operationalize warm handovers to community supports and strengthen role clarity [98,99]. Collectively, these actions make caregiver partnership feasible in time-pressured environments while improving continuity and safety.

4.8. Future Research

Future research should use feasibility and implementation frameworks such as Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) [100,101] and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [102,103] to assess program spread. Priority areas include reach, adoption, fidelity, time, costs, and sustainability. Co-designed outcome measures for caregivers, as well as team and system metrics such as electronic documentation reliability, will be critical to capture the broader impact of caregiver-centered change.

5. Conclusions

The Caregiver-Centered Care Champions Education program extends beyond traditional workforce training by positioning family caregivers and professionals as co-learners and by integrating change management and quality improvement methods with a rights- and values-based competency framework. Participants reported increased knowledge, confidence, and leadership capacity, and they described practical changes in communication, care planning, and advocacy.

By coupling education with implementation strategies such as Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles, stakeholder mapping, and workflow prompts, the program enabled participants to embed caregiver-centered practices in their own contexts. Early outcomes suggest that this model can bridge the gap between individual learning and system change when supported by leadership and organizational policies.

Future work should test the program on a larger scale and evaluate its impact on caregivers, care recipients, and system performance using co-designed outcome measures. Preparing teams to integrate family caregivers as partners in care is both feasible and essential to advancing quality, safety, and sustainability in health and social care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22101593/s1, Supplementary Materials S1: Detailed operational overview of the Caregiver-Centered Care Champions curriculum components, Supplementary Materials S2: Data Collection Instruments. Supplementary Materials S3: Figure S1 Changes in Knowledge and Confidence Pre-Post Education means, Table S1 Paired Samples t-test Pre-Post Champions Education.

Author Contributions

T.L., J.P., S.A., L.C., G.B., D.N., C.P. and M.L. contributed to the design of the study. T.L., J.P., S.A., L.C., G.B., D.N., C.P., M.L., K.S., S.S., C.S., P.W. and S.K. participated in educational design. J.P., T.L. and S.A. collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. T.L. and S.A. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Alberta Health 010785 and Centre for Aging+ Brain Health Innovation (CABHI) SPARKP-4-00460.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study and data collection methods were approved by the University of Alberta’s Health Research Ethics Board (Study ID Pro00138770; Pro00109366; the date of approval, 12 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. After reading the information letter about the study and the ethics consent question, participants provided implied consent by continuing to the education.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The team acknowledges the co-design team of family caregivers, clinicians, educators, managers, decision-makers, and designers from the Learning Design Studio at the University of Alberta who co-designed the Advanced Caregiver-Centered Care Education. We are thankful for the health providers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Cindy Sim is employed by Team CarePal. Jasneet Parmar, Lesley Charles, Kimberly Shapkin, Paige Walker, and Safia Khalfan are employed by Alberta Health Services. Shannon Saunders is employed by Assisted Living Alberta. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zackoff, M.W.; Iyer, S.; Dewan, M. An overarching approach for acute care delivery: Extension of the acute care model to the entire inpatient admission. Transl. Pediatr. 2018, 7, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, G.; Savage, C.; Rafiq, M.; Mazzocato, P. Time-driven activity-based costing in health care: A systematic review of the literature. Health Policy 2017, 121, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anker-Hansen, C.; Skovdahl, K.; McCormack, B.; Tønnessen, S. Invisible cornerstones. A hermeneutic study of the experience of care partners of older people with mental health problems in home care services. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2018, 14, e12214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.F.; Whitney, R.L.; Young, H.M. Family Caregiving in Serious Illness in the United States: Recommendations to Support an Invisible Workforce. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, S451–S456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward-Griffin, C.; Brown, J.B.; Vandervoort, A.; McNair, S.; Dashnay, I. Double-duty caregiving: Women in the health professions. Can. J. Aging 2005, 24, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward-Griffin, C.; Keefe, J.; Martin-Matthews, A.; Kerr, M.; Brown, J.B.; Oudshoorn, A. Development and validation of the double duty caregiving scale. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 41, 108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Fast, J. Value of Family Caregiving in Canada; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2022; p. 2. Available online: https://rapp.ualberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2022/02/Family-caregiving-worth-97-billion_2022-02-20.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Caregivers in Canada 2018, 11-001-X202000821983. 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200108/dq200108a-eng.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Kaufman, B.G.; Zhang, W.; Shibeika, S.; Huang, R.W.; Xu, T.; Ingram, C.; Gustavson, A.M.; Holland, D.E.; Vanderboom, C.; Van Houtven, C.H.; et al. Economic Value of Unpaid Family Caregiver Time Following Hospital Discharge and at End of Life. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2024, 68, 632–640.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilapil, M.; Coletti, D.J.; Rabey, C.; DeLaet, D. Caring for the Caregiver: Supporting Families of Youth With Special Health Care Needs. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2017, 47, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R.; Friedman, E.M.; Martsolf, G.R.; Rodakowski, J.; Everette James, A. Changing Structures and Processes to Support Family Caregivers of Seriously Ill Patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, S36–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberta Health. Improving Quality of Life for Residents in Facility-Based Continuing Care Alberta Facility Based Continuing Care Review; Government of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2021; p. 217. Available online: https://open.alberta.ca/publications/improving-quality-life-residents-facility-based-continuing-care-review-recommendations (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Coe, N.B.; Werner, R.M. Informal Caregivers Provide Considerable Front-Line Support In Residential Care Facilities And Nursing Homes. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, J.; Eales, J.; Kim, C. State of caregiving in Canada (2012 v 2018): Workload intensifies and well-being declines. Research on Aging Practices and Policies; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://rapp.ualberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2023/12/State-of-Caregiving-in-Canada-2012-v-2018_2023.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- MacNeill, L.; Wayne, K.; Luke, A.; Bridges, S.; Besner, J.; Fowler, S.; Doucet, S. Exploring caregiver perspectives on health service delivery priorities for individuals with complex care needs: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Margolis, R.; Verdery, A.; Patterson, S.E. Changes in Family Structure and Increasing Care Gaps in the United States, 2015–2050. Demography 2024, 61, 1403–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearkhani, S.; Bai, Y.Q.; Kuluski, K.; Anderson, G.M.; Wodchis, W.P. Informal Caregiving: Health System Cost Implications. West J. Nurs. Res. 2025, 47, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang-Duah, W.; Rosenberg, M.W. Geographical location as a determinant of caregiver burden: A rural-urban analysis of the informal caregiving, health, and healthcare survey in Ghana. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuvers, M.J.P.; Gedik, A.; Way, K.M.; Elbersen-van de Stadt, S.M.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Husson, O. Caring for Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) with Cancer: A Scoping Review into Caregiver Burdens and Needs. Cancers 2023, 15, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, G.E.; Kovac, K.; Sprajcer, M.; Jay, S.M.; Reynolds, A.C.; Dorrian, J.; Thomas, M.J.W.; Ferguson, S.A. Sleep disturbances in caregivers of children with medical needs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulsara, C.E.; Fynn, N. An exploratory study of GP awareness of carer emotional needs in Western Australia. BMC Fam. Pract. 2006, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carduff, E.; Finucane, A.; Kendall, M.; Jarvis, A.; Harrison, N.; Greenacre, J.; Murray, S.A. Understanding the barriers to identifying carers of people with advanced illness in primary care: Triangulating three data sources. BMC Family Pract. 2014, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, L.; Reinhard, S.; Choula, R. Driving change: Advancing policies to address the escalating complexities and costs of family care. In Bridging the Family Care Gap; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Seplaki, C.L.; Norton, S.A.; Williams, A.M.; Kadambi, S.; Loh, K.P. Communication between Caregivers of Adults with Cancer and Healthcare Professionals: A Review of Communication Experiences, Associated Factors, Outcomes, and Interventions. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophe, V.; Anota, A.; Vanlemmens, L.; Cortot, A.; Ceban, T.; Piessen, G.; Charton, E.; Baudry, A.-S. Unmet supportive care needs of caregivers according to medical settings of cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 9411–9419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horstman, M.J.; Evans, T.L.; Guo, C.; Sonnenfeld, M.; Naik, A.D.; Stevens, A.; Kunik, M.E. Needs of family caregivers of hospitalised adults with dementia during care transitions: A qualitative study in a US Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e087231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Heron, J.; Banamwana, G. Identifying Needs and Support Services for Family Caregivers of Older Community-Based Family Members: Mixed-Method Research Findings. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2025, 44, 1424–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choula, R.B.; Accius, J.C. Home Alone Revisited: Family Caregiver Providing Complex Care. AARP Public Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; 63p, Available online: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/04/home-alone-revisited-family-caregivers-providing-complex-care.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Muntefering, C.; Kastrinos, A.; McAndrew, N.S.; Ahrens, M.; Applebaum, A.J.; Bangerter, L.; Fields, B. Integrating family caregivers in older adults’ hospital stays: A needed cultural shift. Hosp. Pract. 2024, 52, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, J.; Hafeez, S.; L’Heureux, T.; Charles, L.; Tite, J.; Tian, P.; Anderson, S. Family physicians’ preferences for education to support family caregivers: A sequential mixed methods study. Bmc Prim. Care 2024, 25, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbaum, A.; Lipsey, A.; O’Neill, K. Caring in Canada: Survey Insights from Caregivers and Care Providers across Canada. Canadian Centre on Caregiving Excellence. 2024. Available online: https://canadiancaregiving.org/caring-in-canada/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Canadian Centre on Caregiving Excellence. Giving Care: An Approach to a Better Caregiving Landscape in Canada. Canadian Centre on Caregiving Excellence: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://canadiancaregiving.org/giving-care (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Samuelsson, M.; Edman, K.; Neziraj, M.; Ericsson, A. Aiming for survival: A qualitative single case study of support for family members across the care process in outpatient colorectal cancer care. Bmc Cancer 2025, 25, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.; L’Heureux, T.; Anderson, S.; Lobchuk, M.; Charles, L.; Pollard, C.; Powell, L.; Chaudhuri, E.; Fawcett-Arsenault, J.; Mosaico, S.; et al. Bridging the Care Gap: Integrating Family Caregiver Partnerships into Healthcare Provider Education. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.K.; L’Heureux, T.; Anderson, S.; Duggleby, W.; Pollard, C.; Poole, L.; Charles, L.; Sonnenberg, L.K.; Leslie, M.; McGhan, G.; et al. Optimizing the integration of family caregivers in the delivery of person-centered care: Evaluation of an educational program for the healthcare workforce. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.; Anderson, S.; Duggleby, W.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.; Pollard, C.; Brémault-Phillips, S. Developing person-centred care competencies for the healthcare workforce to support family caregivers: Caregiver centred care. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, T.A.S.; van der Hoorn, B.; Fein, E.C. Why Vilifying the Status Quo Can Derail a Change Effort: Kotter’s Contradiction, and Theory Adaptation. J. Change Manag. 2022, 23, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, J.M.; Creasey, T.S. Change Management: The People Side of Change; Prosci Inc.: Loveland, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brusati, I. ADKAR vs Kotter: Which Change Model Should You Choose? Available online: https://www.prosci.com/blog/adkar-vs-kotter#:~:text=A%20flawed%20comparison:%20ADKAR%20is%20not%20the%20Prosci%20Methodology&text=It's%20true%20that%20ADKAR%20is,Model%20for%20organizational%20changes%20efficiently (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Donahue, M.A.; Herman, S.T.; Dass, D.; Farrell, K.; Kukla, A.; Abend, N.S.; Moura, L.M.V.R.; Buchhalter, J.R.; Fureman, B.E. Establishing a learning healthcare system to improve health outcomes for people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 117, 107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheaff, R.; Sherriff, I.; Hennessy, C.H. Evaluating a dementia learning community: Exploratory study and research implications. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, G.L.; Moen, R.; Nolan, K.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Norman, C.L.; Provost, L.P. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.; Woolford, M.; Livingston, P.M.; Lobchuk, M.; Muldowney, A.; Hutchinson, A.M. Informal carer support needs, facilitators and barriers in transitional care for older adults from hospital to home: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 6773–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becqué, Y.N.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; van der Heide, A.; Witkamp, E. Failed implementation of a nursing intervention to support family caregivers: An evaluation study using Normalization Process Theory. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becqué, Y.N.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; van der Heide, A.; Witkamp, E. How nurses support family caregivers in the complex context of end-of-life home care: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.; McLoughlin, K.; Foley, T.; McGilloway, S. Supporting family carers in general practice: A scoping review of clinical guidelines and recommendations. BMC Prim. Care 2023, 24, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe, L.; Lannin, N.; Larcombe, S.; Major, B.; Hoffmann, T.; Lynch, E. Training and education provided to local change champions within implementation trials: A rapid systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2025, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicola, J.; Nataliansyah, M.; Lopez-Olivo, M.; Adegboyega, A.; Hirko, K.; Chichester, L.; Nock, N.; Ginex, P.; Christy, S.; Levett, P. Champions to enhance implementation of clinical and community-based interventions in cancer: A scoping review. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2024, 5, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surr, C.; Sass, c.; Griffiths, A.; Oyebode, J.; Smith, S.; Parveen, S.; Drury, M. Dementia Training Design and Delivery Audit Tool (DeTDAT) v4.0: Auditor’s Manual. 2018; p. 22. Available online: https://www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/-/media/files/research/dementia/dementia-training-design-and-delivery-audit-tool-manual-v4_0.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Surr, C.A.; Gates, C. What works in delivering dementia education or training to hospital staff? A critical synthesis of the evidence. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 75, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surr, C.A.; Gates, C.; Irving, D.; Oyebode, J.; Smith, S.J.; Parveen, S.; Drury, M.; Dennison, A. Effective Dementia Education and Training for the Health and Social Care Workforce: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 87, 966–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, N.; Yufe, S.; Saadatfard, O.; Sockalingam, S.; Wiljer, D. Rebooting kirkpatrick: Integrating information system theory into the evaluation of web-based continuing professional development interventions for interprofessional education. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2017, 37, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.; Galvin, R.; Steinert, Y.; Scherpbier, A.; O’Shaughnessy, A.; Horgan, M.; Horsley, T. A BEME (Best Evidence in Medical Education) systematic review of the use of workplace-based assessment in identifying and remediating poor performance among postgraduate medical trainees. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash Bhatt, A.; Singh, S. Appreciative inquiry: A systematic review and future research agenda. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2025, 38, 664–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M. Team Building and Appreciative Inquiry in Research and Development Teams. Vision 2025, 29, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Lockyer, J.; Touchie, C. Family Physician Quality Improvement Plans: A Realist Inquiry Into What Works, for Whom, Under What Circumstances. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2023, 43, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muirhead, K.; Macaden, L.; Smyth, K.; Chandler, C.; Clarke, C.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C. The characteristics of effective technology-enabled dementia education: A systematic review and mixed research synthesis. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, N.; Lalor, A.; Slatyer, S.; Lee, D.C.A.; Bryant, C.; Watson, M.; Khushu, A.; Burton, E.; Oliveira, D.; Brusco, N.L.; et al. Who cares for the carer? Codesigning a carer health and wellbeing clinic for older care partners of older people in Australia. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 2644–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.E.; Allen, D.; Donnelly, A.; Flynn, J.; Gallacher, K.; Lewis, A.; McCorkle, G.; Mistry, M.; Walkington, P.; Brunton, L. Participatory codesign of patient involvement in a Learning Health System: How can data-driven care be patient-driven care? Health Expect. 2022, 25, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim Lopes, T.S.; Alves, H. Coproduction and cocreation in public care services: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitras, M.-E.; Couturier, Y.; Doucet, E.; Vaillancourt, V.T.; Poirier, M.-D.; Gauthier, G.; Hudon, C.; Delli-Colli, N.; Gagnon, D.; Careau, E.; et al. Co-design, implementation, and evaluation of an expanded train-the-trainer strategy to support the sustainability of evidence-based practice guides for registered nurses and social workers in primary care clinics: A developmental evaluation protocol. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannear, B. The New Zeitgeist: Relationships and Emergence. Medium: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://medium.com/@bill.bannear/the-new-zeitgeist-relationships-and-emergence-e8359b934e0 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Department of Justice. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1982. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/rfc-dlc/ccrf-ccdl/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Byrne, M.; Campos, C.; Daly, S.; Lok, B.; Miles, A. The current state of empathy, compassion and person-centred communication training in healthcare: An umbrella review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2024, 119, 108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, M.J.; Manalili, K.; Zelinsky, S.; Brien, S.; Gibbons, E.; King, J.; Frank, L.; Wallström, S.; Fairie, P.; Leeb, K.; et al. Improving the quality of person-centred healthcare from the patient perspective: Development of person-centred quality indicators. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manderscheid, A. Leveraging Student-Centered Learning Through SMART Goals Within Undergraduate Clinical Experiences. Nurse Educ. 2024, 49, E67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M.; Zvonar, I.; Garrett, A.; Bayaa, N. Making goals count: A theory-informed approach to on-shift learning goals. AEM Educ. Train. 2024, 8, e10993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonk, C.J.; Kim, K.A. Extending sociocultural theory to adult learning. In Adult Learning and Development: Perspectives From Educational Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. An overview on transformative learning. In Lifelong Learning: Concepts and Contexts; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. A critical theory of adult learning and education. In Routledge Library Editions: Education Mini-Set G Higher & Adult Education 11 Vol Set; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; Volume 8, pp. 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, E.J.; de Heer-Koster, M.H.; van der Harst, M.; Browne, J.L.; Scheele, F. Key tips to shift student perspectives through transformative learning in medical education. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Burdine, J.; Thorne, S.; Sandhu, G. Interpretive description: A flexible qualitative methodology for medical education research. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, S.; Nowell, L.; Moules, N.J. Interpretive description in applied mixed methods research: Exploring issues of fit, purpose, process, context, and design. Nurs. Inq. 2023, 30, e12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.C.; Lewis, L.K.; McEvoy, M.P.; Galipeau, J.; Glasziou, P.; Moher, D.; Tilson, J.K.; Williams, M.T. Development and validation of the guideline for reporting evidence-based practice educational interventions and teaching (GREET). BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, M.S.; Smith, W.T.; Kolluru, S.; Sheaffer, E.A.; DiVall, M. A Review of Strategies for Designing, Administering, and Using Student Ratings of Instruction. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.J.; Manalili, K.; Jolley, R.J.; Zelinsky, S.; Quan, H.; Lu, M. How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expect Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2018, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.; L’Heureux, T.; Lewanczuk, R.; Lee, J.; Charles, L.; Sproule, L.; Henderson, I.; Chaudhuri, E.; Berry, J.; Shapkin, K.; et al. Transforming Care Through Co-Design: Developing Inclusive Caregiver-Centered Education in Healthcare. Healthcare 2025, 13, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craswell, A.; Ribeiro, M.; Murdoch, N.; Whitford, S.; Murdoch, T.; Anderson, S.; Parmar, J.; Compton, R. Advancing a relational approach through online education: A mixed methods assessment in older adults’ care. Australas. J. Ageing 2025, 44, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.; Hamilton, K. Progress on theory of planned behavior research: Advances in research synthesis and agenda for future research. J. Behav. Med. 2025, 48, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.M.; Riffin, C.; Bangerter, L.R.; Schaepe, K.; Havyer, R.D. Provider perspectives on integrating family caregivers into patient care encounters. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 57, 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.M.; Kaufman, B.G.; Bangerter, L.; Holland, D.E.; Vanderboom, C.E.; Ingram, C.; Wild, E.M.; Dose, A.M.; Stiles, C.; Thompson, V.H. Improving Transitions in Care for Patients and Family Caregivers Living in Rural and Underserved Areas: The Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2022, 36, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leykum, L.K.; Penney, L.S.; Dang, S.; Trivedi, R.B.; Noël, P.H.; Pugh, J.A.; Shepherd-Banigan, M.E.; Pugh, M.J.; Rupper, R.; Finley, E.; et al. Recommendations to Improve Health Outcomes Through Recognizing and Supporting Caregivers. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, B.; Meera, B.; Istvanek, K.; Ku, T.-L.; Barton, H.J.; Muntefering, C.; Werner, N.E. Using co-design to adapt the care partner hospital assessment tool for dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2025, 17, e70115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, A.R.; Werner, N.E.; Still, C.Z.; Strayer, A.L.; Fields, B.E. Factors associated with care partner identification and education among hospitalized persons living with dementia. PEC Innov. 2024, 5, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, B.; Golden, B.P.; Perepezko, K.; Wyman, M.; Griffin, J.M. Optimizing better health and care for older adults and their family caregivers: A review of geriatric approaches. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 3936–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Lobchuk, M.; Livingston, P.M.; Layton, N.; Hutchinson, A.M. Informal carers’ support needs, facilitators and barriers in the transitional care of older adults: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 2876–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becqué, Y.N.; van der Wel, M.; Aktan-Arslan, M.; Driel, A.G.V.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; van der Heide, A.; Witkamp, E. Supportive interventions for family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncol. 2023, 32, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Beek-Peeters, J.J.A.M.; Faes, M.C.; Habibovic, M.; van der Meer, J.B.L.; Pel-Littel, R.E.; van Geldorp, M.W.A.; Van den Branden, B.J.L.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Minkman, M.M.N. Informal caregivers’ roles and needs regarding shared decision-making in severe aortic stenosis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2025, 131, 108554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarqi, M.N. Assessing the Impact of Multidisciplinary Collaboration on Quality of Life in Older Patients Receiving Primary Care: Cross Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Feng, W.; Zhu, M.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Luo, X.; Shen, J.; Fang, X.; Zhang, T.; et al. A study on the effect of using the video teach-back method in continuous nursing care of stroke patients. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1275447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedzoe, J.; Fänge, A.; Christensen, J.; Lethin, C. Collaborative Learning through a Virtual Community of Practice in Dementia Care Support: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho, M.; Tio, R.; Steinert, Y. Twelve tips for implementing a community of practice for faculty development. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Guccione, L.; Francis, J.; Best, S.; Tavender, E.; Curran, J.; Davies, K.; Rowe, S.; Palmer, V.J.; Klaic, M. Evaluation of research co-design in health: A systematic overview of reviews and development of a framework. Implement. Sci. 2024, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surr, C.A.; Parveen, S.; Smith, S.J.; Drury, M.; Sass, C.; Burden, S.; Oyebode, J. The barriers and facilitators to implementing dementia education and training in health and social care services: A mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker-Hansen, C.; Skovdahl, K.; McCormack, B.; Tonnessen, S. The third person in the room: The needs of care partners of older people in home care services-A systematic review from a person-centred perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, E1309–E1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M.; Hutchison, B.; Abdelhalim, R.; Baker, G.R. Building High-Performing Primary Care Systems: After a Decade of Policy Change, Is Canada “Walking the Talk?”. Milbank Q. 2023, 101, 1139–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.C.; Davies, A.; Abdulhussein, H.; Hooley, F.; Eleftheriou, I.; Hassan, L.; Bromiley, P.A.; Couch, P.; Wasiuk, C.; Brass, A. Educating the Healthcare Workforce to Support Digital Transformation. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 290, 934–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, M.; Iyer, S.; LeBlanc, A.; Roy, M.A.; Abdel-Baki, A. A Rapid-Learning Health System to Support Implementation of Early Intervention Services for Psychosis in Quebec, Canada: Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e37346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludden, T.; O’Hare, K.; Shade, L.; Reeves, K.; Patterson, C.G.; Tapp, H. Implementation of Coach McLungsSM into primary care using a cluster randomized stepped wedge trial design. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.; Kontak, J.; Jeffers, E.; Lawson, B.; MacKenzie, A.; Burge, F.; Boulos, L.; Lackie, K.; Marshall, E.G.; Mireault, A.; et al. Barriers and enablers to implementing interprofessional primary care teams: A narrative review of the literature using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, S.; Lewinski, A.A.; Hwang, S.; Zullig, L.L.; Ball Ricks, K.A.; Ramos, K.; Gordon, A.; Ear, B.; Ballengee, L.A.; Brahmajothi, M.V.; et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation and adoption of improvement coaching: A qualitative evidence synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).