Surgical Education Within Planetary Health Curricula: A Global Environmental Scan (2022–2025)

Abstract

1. Introduction

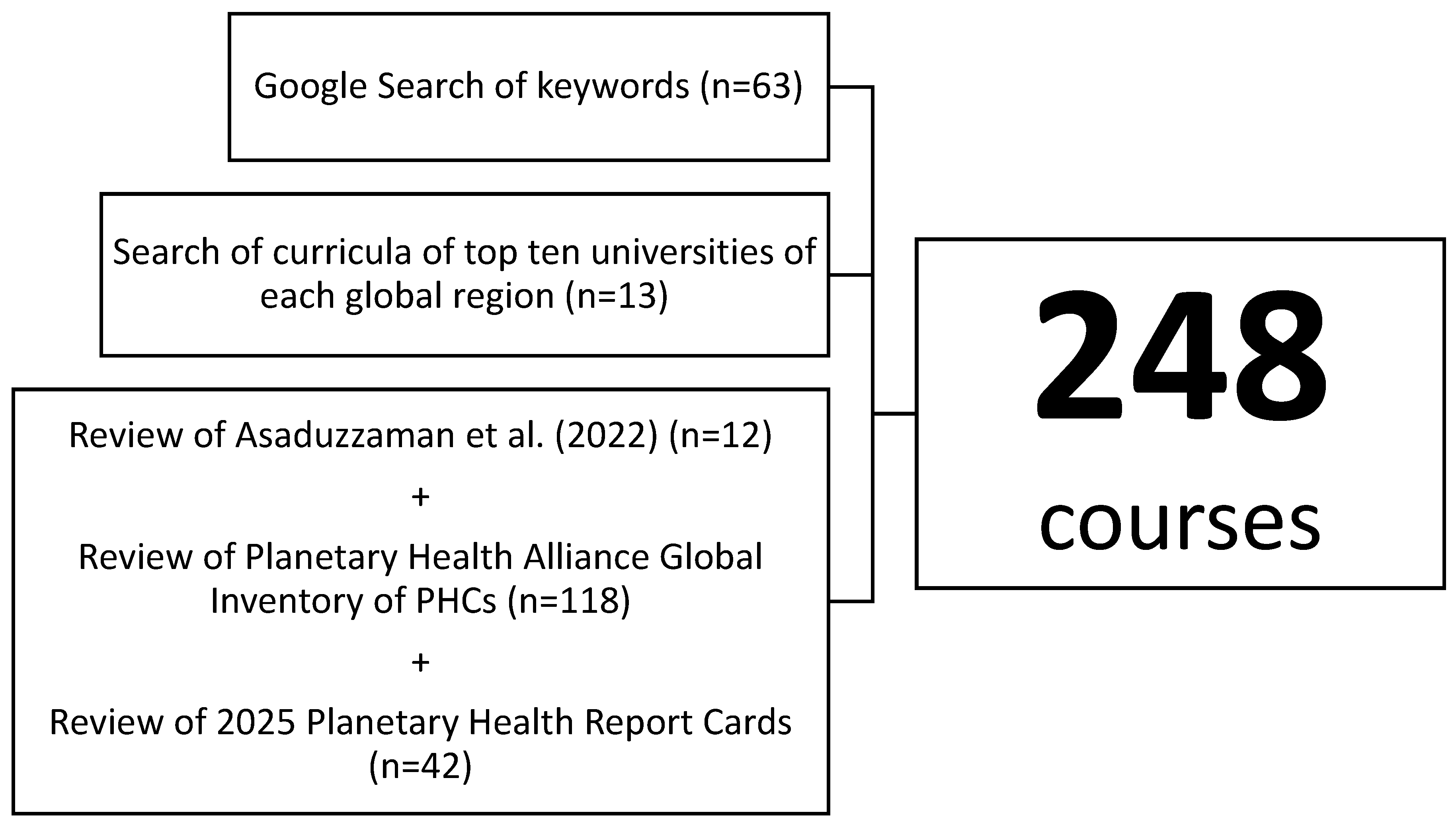

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

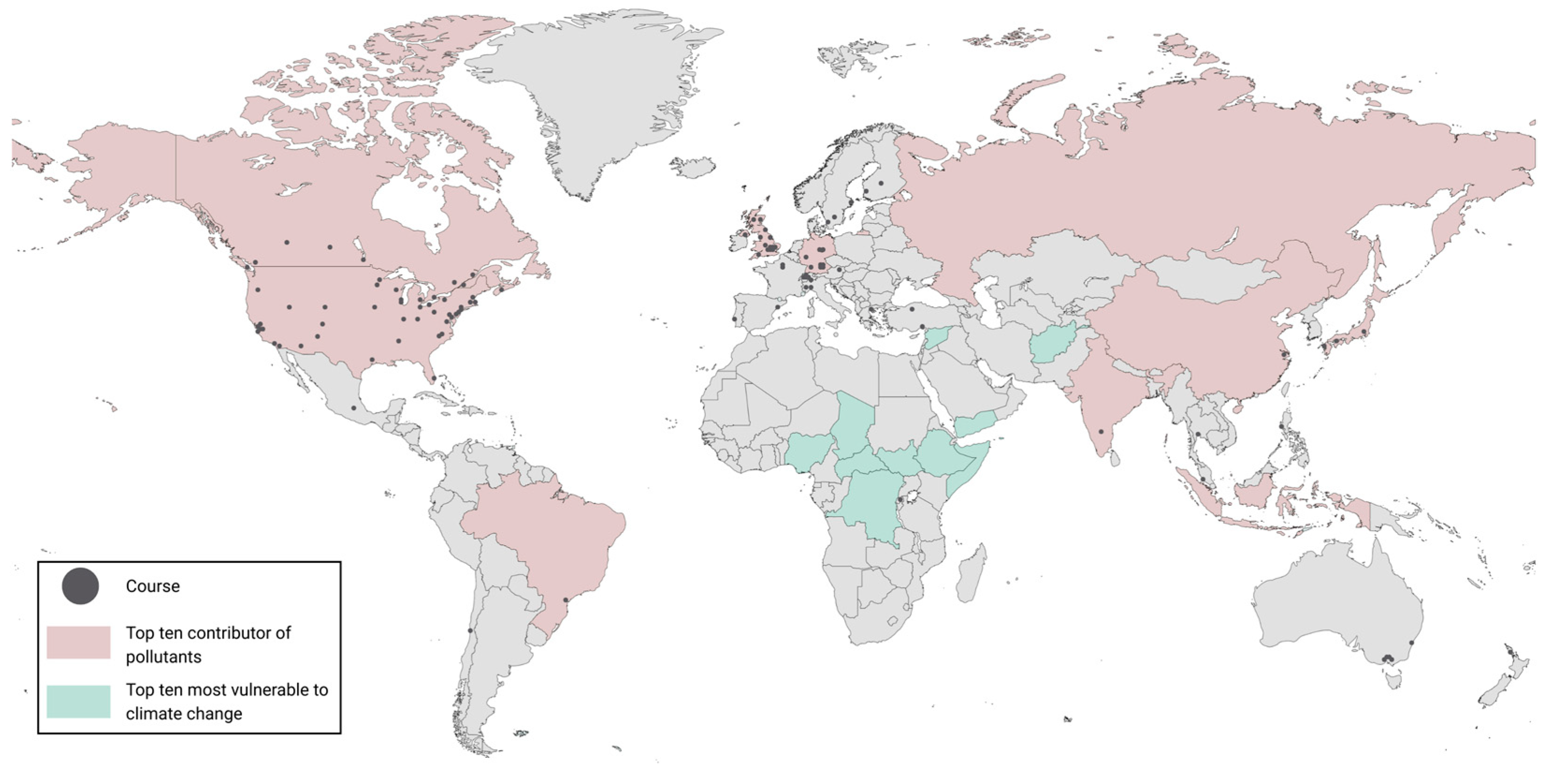

3.1. Geographic Distribution of Courses

3.2. Course Types and Modes of Delivery

3.2.1. Undergraduate and Graduate Courses

3.2.2. Undergraduate and Graduate Programs

3.2.3. Postdoctoral Fellowship

3.2.4. Medical School Courses and Programs

3.2.5. Open Access Courses and Certificate Courses

3.2.6. Professional Development Courses

3.3. Course Duration

3.4. Tuition Costs

3.5. Language Availability

3.6. Surgical Content

4. Discussion

4.1. Disparities in Geographical Distribution

4.2. Integration of Planetary Health Education into Health Professional Training

4.3. Accessibility Barriers

4.4. Gaps in Sustainable Surgery Education

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHC | Planetary Health Course |

| OR | Operating Room |

| LMIC | Low- and middle-income country |

| HIC | High-income country |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

Appendix A

| Regions | # of Courses | % |

|---|---|---|

| North America | 134 | 54.03 |

| Europe | 85 | 34.27 |

| Asia | 11 | 4.44 |

| Oceania | 10 | 4.03 |

| South America | 6 | 2.42 |

| Africa | 1 | 0.40 |

| Global | 1 | 0.40 |

| Course Type | # of Courses | % |

|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate Course | 23 | 9.27 |

| Graduate Course | 52 | 20.97 |

| Undergraduate and Graduate Course | 23 | 9.27 |

| Undergraduate Program | 5 | 2.02 |

| Graduate Program | 25 | 10.08 |

| Medical School | 39 | 15.73 |

| Professional Development Course | 25 | 10.08 |

| Certificate | 25 | 10.08 |

| Open Access Course | 30 | 12.10 |

| Postdoctoral Fellowship | 1 | 0.40 |

| Duration | # of Courses | % |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 week | 53 | 21.37 |

| Less than 1 month | 12 | 4.84 |

| 1 month | 6 | 2.42 |

| 2–4 months | 18 | 7.26 |

| 1 Semester | 83 | 33.47 |

| 5 months–1 year | 2 | 0.81 |

| 1–2 years | 20 | 8.06 |

| 2+ years | 49 | 19.76 |

| Missing | 5 | 2.02 |

| Cost | # of Courses | % |

|---|---|---|

| Free | 49 | 19.76 |

| Less than $1000 USD | 12 | 4.84 |

| $1000–$5000 USD | 21 | 8.47 |

| $5000–$10,000 USD | 25 | 10.08 |

| $10,000–$25,000 USD | 53 | 21.37 |

| $25,000–$50,000 USD | 17 | 6.85 |

| $50,000+ USD | 44 | 17.74 |

| Variable based on country or profession | 21 | 8.47 |

| Missing | 6 | 2.42 |

| Available Languages | # of Courses | % |

|---|---|---|

| Only English | 218 | 87.90 |

| German | 10 | 4.03 |

| Spanish | 6 | 2.42 |

| French | 4 | 1.61 |

| Portuguese | 2 | 0.81 |

| Catalan | 2 | 0.81 |

| Dutch | 2 | 0.81 |

| Turkish | 2 | 0.81 |

| Italian | 1 | 0.40 |

| Swedish | 1 | 0.40 |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

Appendix B.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Appendix B.3. Google Search Strategy

Appendix B.4. Author Data Review

References

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; De Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.; MacNeill, A.J.; Hughes, F.; Alqodmani, L.; Charlesworth, K.; De Almeida, R.; Harris, R.; Jochum, B.; Maibach, E.; Maki, L.; et al. Learning to Treat the Climate Emergency Together: Social Tipping Interventions by the Health Community. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e251–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello, M.; Walawender, M.; Hsu, S.-C.; Moskeland, A.; Palmeiro-Silva, Y.; Scamman, D.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Angelova, D.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Facing Record-Breaking Threats from Delayed Action. Lancet 2024, 404, 1847–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, I.M.; Rasheed, F.N.; Singh, H.; Eckelman, M.J.; Dhimal, M.; Hensher, M.; Guinto, R.R.; McGushin, A.; Ning, X.; Prabhakaran, P.; et al. Evaluating Progress and Accountability for Achieving COP26 Health Programme International Ambitions for Sustainable, Low-Carbon, Resilient Health-Care Systems. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e778–e789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, A.J.; McGain, F.; Sherman, J.D. Planetary Health Care: A Framework for Sustainable Health Systems. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e66–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Sherman, J.D.; MacNeill, A.J. Life Cycle Environmental Emissions and Health Damages from the Canadian Healthcare System: An Economic-Environmental-Epidemiological Analysis. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Huang, K.; Lagasse, R.; Senay, E.; Dubrow, R.; Sherman, J.D. Health Care Pollution And Public Health Damage In The United States: An Update: Study Examines Health Care Pollution and Public Health Damage in the United States. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2020, 39, 2071–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennison, I.; Roschnik, S.; Ashby, B.; Boyd, R.; Hamilton, I.; Oreszczyn, T.; Owen, A.; Romanello, M.; Ruyssevelt, P.; Sherman, J.D.; et al. Health Care’s Response to Climate Change: A Carbon Footprint Assessment of the NHS in England. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e84–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeill, A.J.; Lillywhite, R.; Brown, C.J. The Impact of Surgery on Global Climate: A Carbon Footprinting Study of Operating Theatres in Three Health Systems. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e381–e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, J.; Weiser, T.G.; Hider, P.; Wilson, L.; Gruen, R.L.; Bickler, S.W. Estimated Need for Surgery Worldwide Based on Prevalence of Diseases: A Modelling Strategy for the WHO Global Health Estimate. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, S13–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.A.F.; Aguirre, A.A.; Astle, B.; Barros, E.; Bayles, B.; Chimbari, M.; El-Abbadi, N.; Evert, J.; Hackett, F.; Howard, C.; et al. A Framework to Guide Planetary Health Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e253–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguin, N.; Selvam, R.; Moloo, H. Contextually Relevant Healthcare Professional Education: Why Planetary Health Is Essential in Every Curriculum Now. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 4, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, M.; Madden, L.; Maxwell, J.; Schwerdtle, P.N.; Richardson, J.; Singleton, J.; MacKenzie-Shalders, K.; Behrens, G.; Cooling, N.; Matthews, R.; et al. Planetary Health: Educating the Current and Future Health Workforce. In Clinical Education for the Health Professions; Nestel, D., Reedy, G., McKenna, L., Gough, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-981-13-6106-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, D.; Townsend, C.B.; Tulipan, J.; Ilyas, A.M. Economic and Environmental Impacts of the Wide-Awake, Local Anesthesia, No Tourniquet (WALANT) Technique in Hand Surgery: A Review of the Literature. J. Hand Surg. Glob. Online 2022, 4, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambrin, C.; De Souza, S.; Gariel, C.; Chassard, D.; Bouvet, L. Association Between Anesthesia Provider Education and Carbon Footprint Related to the Use of Inhaled Halogenated Anesthetics. Anesth. Analg. 2023, 136, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Hollandsworth, H.M.; Alseidi, A.; Scovel, L.; French, C.; Derrick, E.L.; Klaristenfeld, D. Environmentalism in Surgical Practice. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2016, 53, 165–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, A.J.; Hopf, H.; Khanuja, A.; Alizamir, S.; Bilec, M.; Eckelman, M.J.; Hernandez, L.; McGain, F.; Simonsen, K.; Thiel, C.; et al. Transforming The Medical Device Industry: Road Map To A Circular Economy: Study Examines a Medical Device Industry Transformation. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2088–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, D. Sustainability in the Operating Room. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2020, 38, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, S.K.; Culver, L.G.; Maroon, J. Green Operating Room—Current Standards and Insights From a Large North American Medical Center. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaduzzaman, M.; Ara, R.; Afrin, S.; Meiring, J.E.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M. Planetary Health Education and Capacity Building for Healthcare Professionals in a Global Context: Current Opportunities, Gaps and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, S.; O’Fallon, L. The Emergence of Environmental Health Literacy—From Its Roots to Its Future Potential. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K. From Content Knowledge to Community Change: A Review of Representations of Environmental Health Literacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022–2023 Best Global Universities Rankings. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/rankings (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Find a Planetary Health Course. Available online: https://planetaryhealthalliance.org/planetary-health-courses/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Medicine. Available online: https://phreportcard.org/medicine/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Evans, S. Analysis: Which Countries Are Historically Responsible for Climate Change?—Carbon Brief. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-which-countries-are-historically-responsible-for-climate-change/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- 10 Countries at Risk of Climate Disaster. Available online: https://www.rescue.org/article/10-countries-risk-climate-disaster (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Talukder, B.; Ganguli, N.; Choi, E.; Tofighi, M.; Vanloon, G.W.; Orbinski, J. Exploring the Nexus: Comparing and Aligning Planetary Health, One Health, and EcoHealth. Glob. Transit. 2024, 6, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planetary Health Postdoctoral Fellowship. Available online: https://globalhealth.stanford.edu/programs/post-doctoral-fellowship-in-planetary-health/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- TelessaúdeRS-UFRGS. Available online: https://telessauders.ufrgs.br/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Low & Middle Income. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/low-and-middle-income (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Bondell, H.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Moore, S.E. Environmental, Institutional, and Demographic Predictors of Environmental Literacy among Middle School Children. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargawa, R.; Bhargava, M. The Climate Crisis Disproportionately Hits the Poor. How Can We Protect Them? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/01/climate-crisis-poor-davos2023/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Klingelhöfer, D.; Müller, R.; Braun, M.; Brüggmann, D.; Groneberg, D.A. Climate Change: Does International Research Fulfill Global Demands and Necessities? Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A Review of the Global Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Sustainable Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muttarak, R.; Lutz, W. Is Education a Key to Reducing Vulnerability to Natural Disasters and Hence Unavoidable Climate Change? Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, art42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, O.; Wang, H.; Velauthapillai, K.; Walker, C. An Approach to Implementing Planetary Health Teaching in Medical Curricula. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2022, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, E.H.; Oosterveld, B.; Slootweg, I.A.; Vos, H.M.M.; Adriaanse, M.A.; Schoones, J.W.; Brakema, E.A. The Development and Characteristics of Planetary Health in Medical Education: A Scoping Review. Acad. Med. 2024, 99, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planetary Health Curriculum Integration Project. Available online: https://globalhealth.med.ubc.ca/service/student-groups/global-health-initiative/planetary-health-curriculum-integration-project/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Climate Education Grants Announced|Climate Emergency. Available online: https://climateemergency.ubc.ca/climate-education-grants-announced/?_gl=1*13g8wv7*_ga*NzQyMzIyNDI0LjE3MDgwMjU4Nzc.*_ga_994J7095HS*MTcwOTA2NTI4MS4xLjEuMTcwOTA2NTYwOS4wLjAuMA.*_gcl_au*MTU3MjI1OTEyMy4xNzA5MDY1Mjgx (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Card, K.; Takaro, T.; Lanphear, B.; Buse, C.; Byers, K.; Tairyan, K.; Ardiles, P.; Kennedy, A.; Tsakonas, K.; Winters, M.; et al. SFU’s Medical School Needs to Be Grounded in Planetary Health—An Open Letter. Available online: https://mhcca.ca/medschool (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Trilling, D. Bringing Climate Change into Medical School. Available online: https://salatainstitute.harvard.edu/bringing-climate-change-into-medical-school/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Climate Change & Medical Schools. Available online: https://ifmsa.org/climate-change-medical-schools/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- European Network on Climate & Health Education (ENCHE). Available online: https://www.gla.ac.uk/explore/internationalisation/enche/#enchemembers (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Universidad de Concepción Invita a Conformar La Red Chilena de Salud Planetaria. Available online: https://www.tvu.cl/prensa/2025/09/15/universidad-de-concepcion-invita-a-conformar-la-red-chilena-de-salud-planetaria.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- How Health Systems in Asia Are Adapting to Climate Change Impacts. Available online: https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/how-health-systems-asia-are-adapting-climate-change-impacts (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Govind, S.; Velmurugan, A.; Mariyam, D. The State of Climate-Health in Medical Education in India—A Pilot Study. J. Clim. Change Health 2022, 8, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Impact of Climate Change on Emergency Healthcare in India: Research by Prof. Caleb Dresser. Available online: https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/2025/05/the-impact-of-climate-change-on-emergency-healthcare-in-india/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Citizen Doctor Course. Available online: https://stjohns.in/medicalcollege/Citizen_Doctor_Course.php (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Affleck, A.; Roshan, A.; Stroshein, S.; Walker, C.; Luo, O.D. CFMS HEART: National Report on Planetary Health Education 2021; Canadian Federation of Medical Students Health and Environment Committee: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://www.cfms.org/files/HEART/CFMSHEARTNationalReportonPlanetaryHealthEducation2021.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Johnston, N.; Rogers, M.; Cross, N.; Sochan, A. Global and Planetary Health: Teaching as If the Future Matters. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2005, 26, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kötter, T.; Hoschek, M.; Pohontsch, N.J.; Steinhäuser, J. Planetary Health in der curricularen Lehre im Fach Humanmedizin—eine qualitative Studie zur Evaluation einer Lehr-/Lernintervention. Z. Evidenz Fortbild. Qual. Im Gesundheitswesen 2023, 179, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotcher, J.; Maibach, E.; Miller, J.; Campbell, E.; Alqodmani, L.; Maiero, M.; Wyns, A. Views of Health Professionals on Climate Change and Health: A Multinational Survey Study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e316–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritcey, G.; Burra, T.; Byers, E.; Gardner, K.; Gurney, L.; Fallis, J.; MacNeill, A.J.; Moloo, H.; Muniak, A.; Piche, A.; et al. Training for Better Health Outcomes: Integrating Sustainability into Healthcare Quality Improvement Education Version 1.0. Available online: https://cascadescanada.ca/resources/integrating-sustainability-into-healthcare-quality-improvement-education-playbook/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Connor, A.; O’Donoghue, D. Sustainability: The Seventh Dimension of Quality in Health Care. Hemodial. Int. 2012, 16, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, S.; Ingham, J.; Cheshire, M.; Went, S. Defining Quality and Quality Improvement. Clin. Med. Lond. Engl. 2010, 10, 537–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossebaard, H.C.; Lachman, P. Climate Change, Environmental Sustainability and Health Care Quality. Int. J. Qual. Health Care J. Int. Soc. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, mzaa036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BC Health Quality Matrix. Available online: https://healthqualitybc.ca/bc-health-quality-matrix/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Michael, F. Lovenheim Resource Barriers to Postsecondary Educational Attainment. Available online: https://www.nber.org/reporter/2017number3/resource-barriers-postsecondary-educational-attainment (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Cengage Group Barriers to Post-Secondary Education. Available online: https://cengage.widen.net/s/w52pbrzwlm/cg_barrierspostsecedreport_final (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Floss, M.; Abelsohn, A.; Kirk, A.; Khoo, S.-M.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Umpierre, R.N.; McGushin, A.; Yoon, S. An International Planetary Health for Primary Care Massive Open Online Course. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e172–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.T.; Smith, E.A. An Analysis of the Hanson-Liethen Sliding Scale Cost Recovery Model for College Tuition: A Case Study. Glob. J. Educ. Stud. 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, J.F.; Oakley, B. Scaling online education: Increasing access to higher education. Online Learn. 2019, 14, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASCADES—Home. Available online: https://cascadescanada.ca/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Nazir, A.; Ma, X.; Vervoort, D. Environmentally Sustainable Surgical Health Systems: An Analysis of Policies, Tools, and Guidelines. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e538–e539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Pizarro, P.; Koch, S.; Muret, J.; Trinks, A.; Brazzi, L.; Reinoso-Barbero, F.; Diez Sebastian, J.; Mrf Struys, M. Environmental Sustainability in the Operating Room: A Worldwide Survey among Anaesthesiologists. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Care 2023, 2, e0025-1-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meara, J.G.; Leather, A.J.M.; Hagander, L.; Alkire, B.C.; Alonso, N.; Ameh, E.A.; Bickler, S.W.; Conteh, L.; Dare, A.J.; Davies, J.; et al. Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and Solutions for Achieving Health, Welfare, and Economic Development. Lancet 2015, 386, 569–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, L.; Velin, L.; Tudravu, J.; McClain, C.D.; Bernstein, A.; Meara, J.G. Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities to Scale up Surgical, Obstetric, and Anaesthesia Care Globally. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e538–e543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaigham, M.; Bryce-Alberti, M.; Calderon, C.; Campos, L.N.; Raguveer, V.; Nuss, S.; Dutta, R.; Naus, A.E.; Forbes, C.; Park, K.B.; et al. The Time to Act Is Now: A Call to Action on Planetary Health and Sustainable Surgical Systems. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e931–e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, M.F.; Pellino, G. Environmental Effects of Surgical Procedures and Strategies for Sustainable Surgery. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Mas, F.; Previtali, P.; Denicolai, S.; Alvaro, M.; Biancuzzi, H.; Campostrini, S.; Cutti, S.; Grancini, G.; Magnani, G.; Re, B.; et al. Towards the Healthcare of the Future. A Delphi Consensus on Environmental Sustainability Issues. In Towards the Future of Surgery; Martellucci, J., Dal Mas, F., Eds.; New Paradigms in Healthcare; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 189–209. ISBN 978-3-031-47622-8. [Google Scholar]

- Almukhtar, A.; Batcup, C.; Bowman, M.; Winter-Beatty, J.; Leff, D.; Demirel, P.; Porat, T.; Judah, G. Barriers and Facilitators to Sustainable Operating Theatres: A Systematic Review Using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 110, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syllabi Directory—Planetary Health Higher Education. Available online: https://planetaryhealthalliance.org/for-educators/syllabi-directory/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Reports Focus on Role of Universities in Achieving SDGs—SDG Knowledge Hub. Available online: https://sdg.iisd.org/news/reports-focus-on-role-of-universities-in-achieving-sdgs/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Delivering a Net Zero NHS. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/a-net-zero-nhs/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Sustainable Practice. Available online: https://www.hcpc-uk.org/standards/meeting-our-standards/sustainable-practice/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Hough, E.; Cohen Tanugi-Carresse, A. Supporting Decarbonization of Health Systems—A Review of International Policy and Practice on Health Care and Climate Change. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vayalikunnel, R.; Zanotto Manoel, P.; Zanotto Manoel, A.; Jeyakumar, M.; Chen, L.Q.; Jeyakumar, R.; Balmes, P.; Lalande, A.; MacNeill, A.J.; Joharifard, S.; et al. Surgical Education Within Planetary Health Curricula: A Global Environmental Scan (2022–2025). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101545

Vayalikunnel R, Zanotto Manoel P, Zanotto Manoel A, Jeyakumar M, Chen LQ, Jeyakumar R, Balmes P, Lalande A, MacNeill AJ, Joharifard S, et al. Surgical Education Within Planetary Health Curricula: A Global Environmental Scan (2022–2025). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101545

Chicago/Turabian StyleVayalikunnel, Rosemary, Poliana Zanotto Manoel, Agnes Zanotto Manoel, Mathanky Jeyakumar, Le Qi Chen, Rushan Jeyakumar, Patricia Balmes, Annie Lalande, Andrea J. MacNeill, Shahrzad Joharifard, and et al. 2025. "Surgical Education Within Planetary Health Curricula: A Global Environmental Scan (2022–2025)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101545

APA StyleVayalikunnel, R., Zanotto Manoel, P., Zanotto Manoel, A., Jeyakumar, M., Chen, L. Q., Jeyakumar, R., Balmes, P., Lalande, A., MacNeill, A. J., Joharifard, S., & Joos, E. (2025). Surgical Education Within Planetary Health Curricula: A Global Environmental Scan (2022–2025). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101545