Co-Design with Rural Adolescents to Inform a School-Based Physical Activity and Social Media Literacy Intervention: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

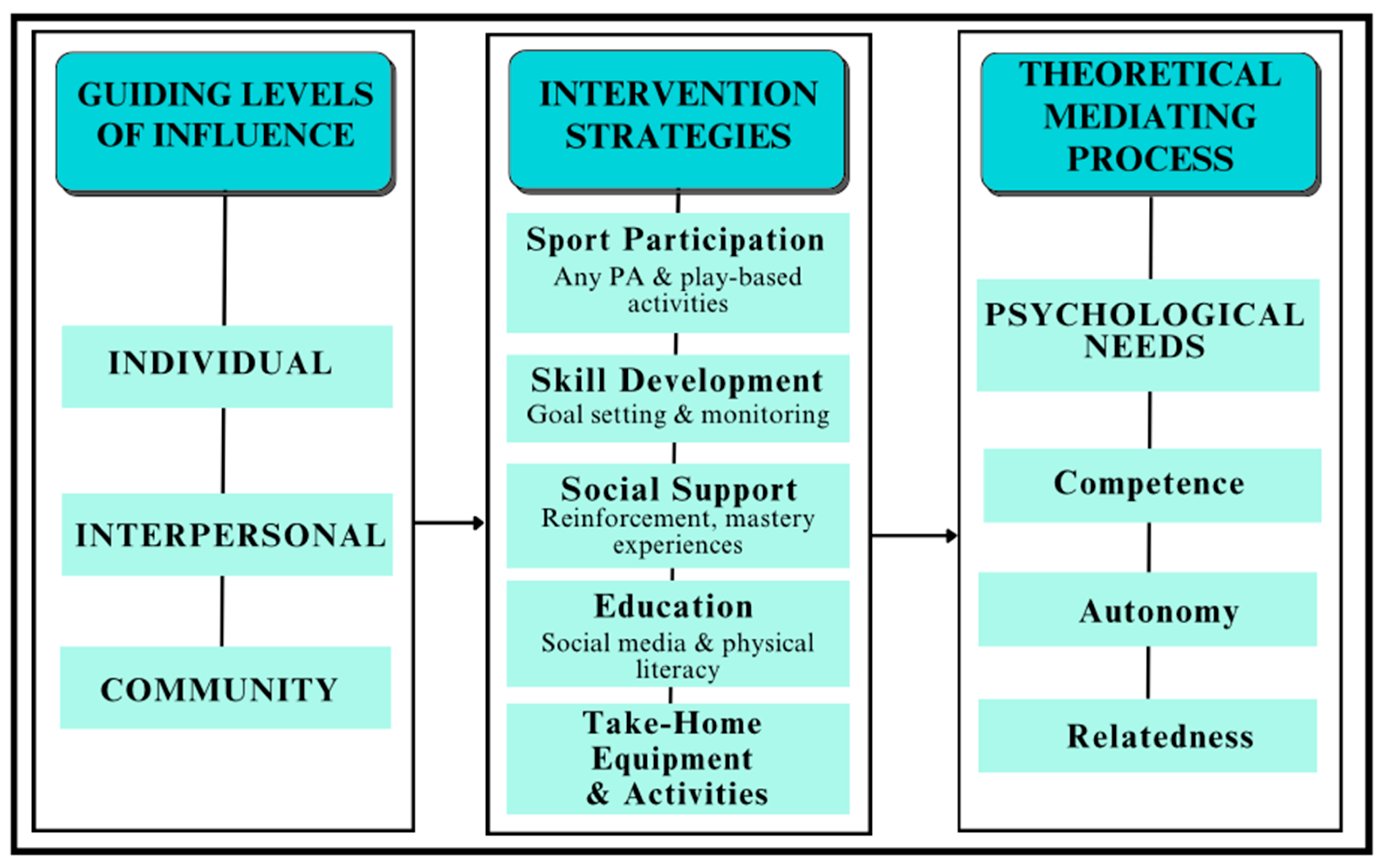

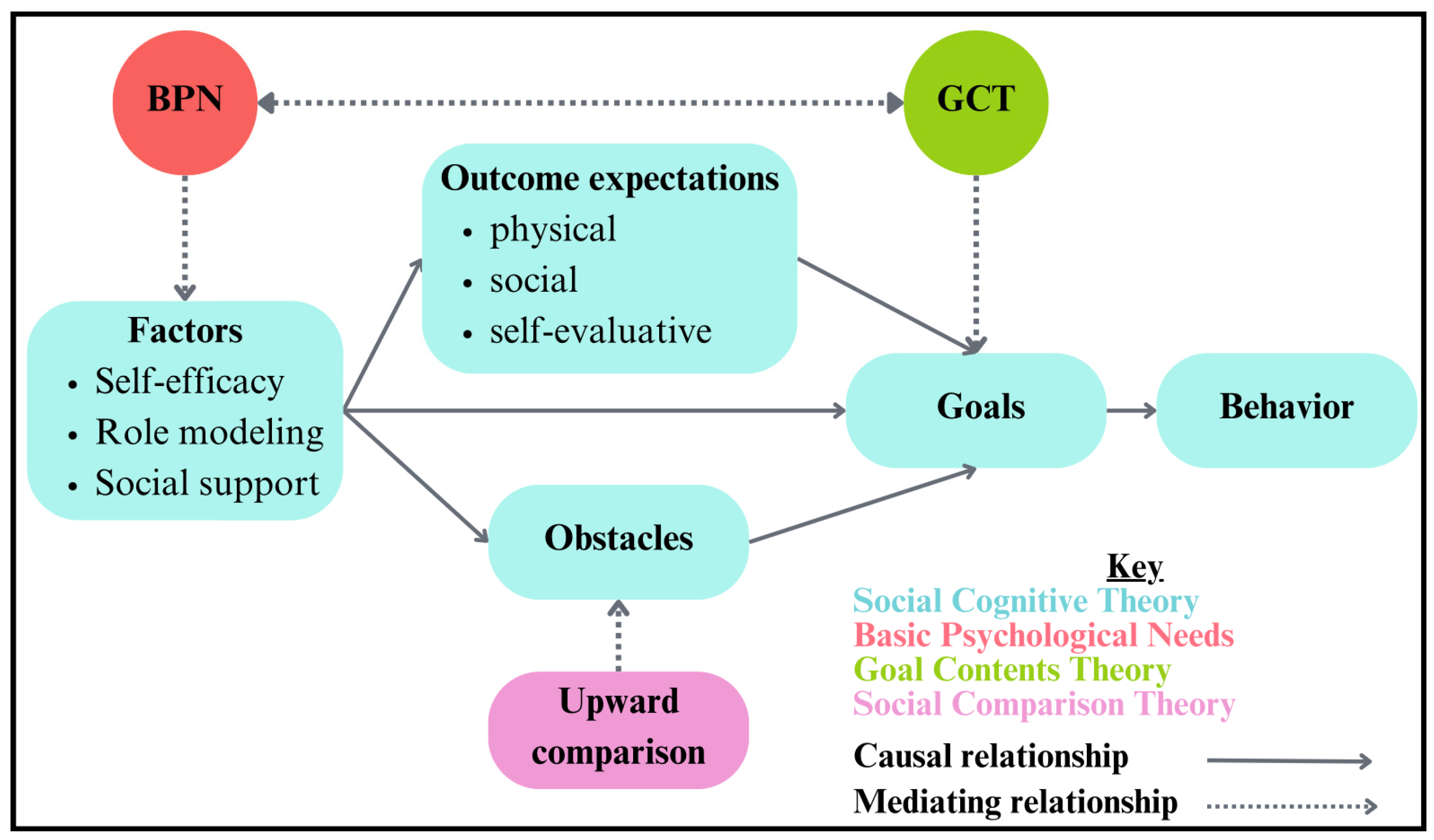

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Participants and Procedures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Theme 1: Autonomy

3.3. Theme 2: Relatedness

3.4. Theme 3: Competence

3.5. Theme 4: Extrinsic Motivation

3.6. Theme 5: Intrinsic Motivation

3.7. Theme 6: Social Comparison

3.8. Intervention Design Implications

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological Needs and Physical Activity

4.2. Psychological Needs and Social Media Use

4.3. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in Physical Activity

4.4. Motivations for Social Media Use

4.5. Social Comparison and Body Image

4.6. Implications for Intervention Development

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2022 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, e153–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, F.; Melvin, S.C.; Bell, R.A.; Zhao, G. Global Responses to Prevent, Manage, and Control Cardiovascular Diseases. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2022, 19, 220347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Activity Alliance. 2024 U.S. Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth; Physical Activity Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://paamovewithus.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2024-US-Report-Card-Executive-Summary_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Cao, Z.B.; Chen, P.J.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.Y. Associations between parental support for physical activity and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among Chinese school children: A cross-sectional study. J. Sport Health Sci. 2017, 6, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.T.; Feng, J.Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Lao, X.Q.; Chen, J.X.; Tan, K.C.; Wong, M.; Mo, P.K.; Wang, M.P.; Lam, T.H. Associations between various kinds of parental support and physical activity among children and adolescents in Shanghai, China: Gender and age differences. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, A.D.; Hinckson, E.A.; Water, T.C.A. Physical activity is not play: Perceptions of children and parents from deprived areas. N. Z. Med. J. 2012, 125, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peralta, L.R.; Mihrshahi, S.; Bellew, B.; Reece, L.J.; Hardy, L.L. The Barriers to and Facilitators of Physical Activity and Sport for Oceania with Non-European, Non-Asian (ONENA) Ancestry Children and Adolescents: A Mixed Studies Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; Nelson, M.C.; Page, P.; Popkin, B.M. Inequality in the Built Environment Underlies Key Health Disparities in Physical Activity and Obesity. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecamo, S.E.; Xu, H.; Goldberg, L.R.; Fretts, A.M.; Sitlani, C.M.; Enquobahrie, D.A.; Odden, M.C.; Longstreth, W.T.; Psaty, B.M.; Mukamal, K.J. Association of Rurality with Risk of Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Abshire, D.A.; Wirth, M.D.; Hung, P.; Benavidez, G.A. Rural–Urban Differences in Overweight and Obesity, Physical Activity, and Food Security Among Children and Adolescents. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, 230136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Roy, K.; Khushalani, J.S.; Puddy, R.W. Trend in rural-urban disparities in access to outpatient mental health services among US adults aged 18-64 with employer-sponsored insurance: 2005–2018. J. Rural Health 2022, 38, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegler, M.C.; Raskind, I.G.; Comeau, D.L.; Griffith, D.M.; Cooper, H.L.; Shelton, R.C. Inequities in Physical Activity Environments and Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Rural Communities. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2022, 19, 210417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaraman, L.; Richer, A.M.; Liu, C.; Lynch, A.D.; Moreno, M.A. Early Adolescent Social Media–Related Body Dissatisfaction: Associations with Depressive Symptoms, Social Anxiety, Peers, and Celebrities. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2021, 42, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Xiong, D.; Jiang, T.; Song, L.; Wang, Q. Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2019, 13, Article 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image 2015, 13, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. Social Media and Youth Mental Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pedalino, F.; Camerini, A.L. Instagram Use and Body Dissatisfaction: The Mediating Role of Upward Social Comparison with Peers and Influencers among Young Females. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Tian, Y. The Impact of Problematic Social Media Use on Inhibitory Control and the Role of Fear of Missing Out: Evidence from Event-Related Potentials. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartberg, L.; Thomasius, R.; Paschke, K. The relevance of emotion regulation, procrastination, and perceived stress for problematic social media use in a representative sample of children and adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Dogra, N.; Whiteman, N.; Hughes, J.; Eruyar, S.; Reilly, P. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Fu, G.; Huang, J. The double-edged sword effects of active social media use on loneliness: The roles of interpersonal satisfaction and fear of missing out. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1059598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruzan, K.P.; Whitlock, J.; Bazarova, N.N. The role of social media in suicide and self-injury: A systematic review. Internet Interv. 2022, 30, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, B.; Rizzolo, D. The Effects of Social Media on Adolescent Mental Health. Pediatr. Neonatal Nurs. 2022, 8, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Lima, P.; Higgins, A. Social media engagement and Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) in primary school children. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2021, 37, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerkan, M.; Rangul, V.; Skjesol, K.; Ulstad, S.O. Physical Activity and Depression/Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents—The Young-HUNT Study. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 6, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashdown-Franks, G.; Sabiston, C.M.; Solomon-Krakus, S.; O’Loughlin, J.L. Sport participation in high school and anxiety symptoms in young adulthood. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 12, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandola, A.; Stubbs, B. Exercise and Anxiety. In Anxiety Disorders; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Cavarretta, D.J.; Hall, E.E.; Bixby, W.R. The acute effects of resistance exercise on affect, anxiety, and mood—Practical implications for designing resistance training programs. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 12, 295–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher Dimech, A.; Seiler, R. Extra-curricular sport participation: A potential buffer against social anxiety symptoms in primary school children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddervold, S.; Haug, E.; Kristensen, S.M. Sports participation, body appreciation and life satisfaction in Norwegian adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2024, 52, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.E.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Markham, C.M.; Kok, G. Intervention Mapping: Theory- and Evidence-Based Health Promotion Program Planning: Perspective and Examples. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 209. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.M.; Greeven, S.J.; Heeter, K.N.; Brunnemer, J.E.; Otile, J.; Fernández Solá, P.A.; Dutta, S.; Hobson, J.M.; Evanovich, J.M.; Coble, C.J.; et al. Human-centered participatory co-design with children and adults for a prototype lifestyle intervention and implementation strategy in a rural middle school. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, S.M.; Powell, L.H.; Adler, N.; Naar-King, S.; Reynolds, K.D.; Hunter, C.M.; Laraia, B.; Olster, D.H.; Perna, F.M.; Peterson, J.C.; et al. From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Powdthavee, N. Social Comparison Theory. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6028–6029. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.C.; Tandon, S.D.; Islam, N.; Riley, L.; Trinh-Shevrin, C. Applying a community-based participatory research framework to patient and family engagement in the development of patient-centered outcomes research and practice. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraguela-Vale, R.; Varela-Garrote, L.; Carretero-García, M.; Peralbo-Rubio, E.M. Basic Psychological Needs, Physical Self-Concept, and Physical Activity Among Adolescents: Autonomy in Focus. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Feu, S.; Gamero, M.G.; Ibáñez, S.J. Structural Relationship between Psychological Needs and Sport Adherence for Students Participating in Physical Education Class. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aart, I.; Hartman, E.; Elferink-Gemser, M.; Mombarg, R.; Visscher, C. Relations among basic psychological needs, PE-motivation and fundamental movement skills in 9–12-year-old boys and girls in Physical Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2017, 22, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Raudsepp, L.; Koka, A. Perceived Autonomy Support from Peers, Parents, and Physical Education Teachers as Predictors of Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents—A One-Year Longitudinal Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Polet, J.; Hassandra, M.; Lintunen, T.; Laukkanen, A.; Hankonen, N.; Hirvensalo, M.; Tammelin, T.H.; Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. Testing a physical education-delivered autonomy supportive intervention to promote leisure-time physical activity in lower secondary school students: The PETALS trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Thomas, K.T.; Chen, Y.L. The Role of Perceived and Actual Motor Competency on Children’s Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness During Middle Childhood. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A.D.; Smedegaard, S.; Pawlowski, C.S.; Skovgaard, T.; Christiansen, L.B. Pupils’ experiences of autonomy, competence and relatedness in ‘Move for Well-being in Schools’: A physical activity intervention. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Duncheon, N.; McDavid, L. Peers and Teachers as Sources of Relatedness Perceptions, Motivation, and Affective Responses in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2009, 80, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.L.; McLellan, R. Adolescents’ motivation to use social network sites from a psychological needs perspective. J. Adolesc. 2024, 96, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Casteele, M.; Mabbe, E.; Verbeken, S.; Moens, E.; Braet, C. Unraveling the Role of Social Media on Adolescents’ Daily Goals and Affect: The Interplay Between Basic Psychological Needs and Screen Time. Interact. Comput. 2024, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.; Rice, S.; Vella-Brodrick, D. Adolescent Social Media Use through a Self-Determination Theory Lens: A Systematic Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliandolo, M.C.; Costa, S.; Kuss, D.J.; Cuzzocrea, F.; Verrastro, V. Technological Addiction in Adolescents: The Interplay Between Parenting and Psychological Basic Needs. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogg, K.A.; Vaughn, A.A.; Levy, S.S.; Blashill, A.J. Motivation for Physical Activity among U.S. Adolescents: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litt, D.M.; Iannotti, R.J.; Wang, J. Motivations for Adolescent Physical Activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granero-Gallegos, A.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Sánchez-Fuentes, A.; Martínez-Molina, M. Motivational profiles of autonomy support, self-determination, satisfaction, importance of physical education and intention to partake in leisure time physical activity. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2014, 14, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; Franco-García, J.M.; Mayordomo-Pinilla, N.; Pazzi, F.; Galán-Arroyo, C. Physical Activity and Emotional Regulation in Physical Education in Children Aged 12–14 Years and Its Relation with Practice Motives. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, D.J.; Smith, R.E.; Smoll, F.L.; Cumming, S.P. Parent initiated motivational climate and young athletes’ intrinsic-extrinsic motivation: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relations. J. Child Adolesc. Behav. 2013, 1, 1000103. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Huang, C.; Liu, T.; Xiong, W. The role of parents in the motivation of young athletes: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1295000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, N.G.; Başak, B. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations of Social Media Use: College Students Perspective. Online J. Qual. High. Educ. 2018, 5, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- McComb, S.E.; Mills, J.S. Young women’s body image following upwards comparison to Instagram models: The role of physical appearance perfectionism and cognitive emotion regulation. Body Image 2021, 38, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M.; Slater, A. NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, S. Adolescent constructions of gendered identities: The role of sport and (physical) education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, N.; Drummond, C.; Abery, L.; Elliott, S.; Pennesi, J.L.; Prichard, I. More opportunities, same challenges: Adolescent girls in sports that are traditionally constructed as masculine. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendle, J.; Turkheimer, E.; Emery, R.E. Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Dev. Rev. 2007; 27, 151–171. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Any Anxiety Disorder. NIMH. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/any-anxiety-disorder (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Grabe, S.; Ward, L.M.; Hyde, J.S. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol Bull. 2008, 134, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perloff, R.M. Social Media Effects on Young Women’s Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles 2024, 71, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, R.C.; Melchiori, F.; Teti, A.; Albano, G.; Raffard, S.; Rodgers, R.; Lo Coco, G. The association between social comparison in social media, body image concerns and eating disorder symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image 2025, 52, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffey, K.; Barbosa, A.; Whiting, S.; Mendes, R.; Yordi Aguirre, I.; Tcymbal, A.; Abu-Omar, K.; Gelius, P.; Breda, J. Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity Participation in Adolescent Girls: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 743935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.M.; Goss, J.M.; Major, M.G.; Kwaiser, M.M.; Medellin, A.M.; Hobson, J.M.; Martinez Kercher, V.M.; Kercher, K.A. Refined Feasibility Testing of an 8-Week Sport and Physical Activity Intervention in a Rural Middle School. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.M.; Brunnemer, J.E.; Heeter, K.N.; Medelin, A.M.; Churchill, W.C.; Goss, J.M.; Hobson, J.M.; Werner, N.E.; Weaver, R.G.; Kercher, V.M.M.; et al. Evaluating the feasibility and acceptability of a co-designed physical activity intervention for rural middle schoolers: A pilot study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J.; Robertson, T. Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship; UNICEF International Child Development Centre: Florence, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lundy, L. ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Reyes, M.; Muñoz Serrano, M.; Van den Broucke, S. How do universities implement the Health Promoting University concept? Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Watkins, J.M.; Goss, J.M.; Schigur, A.P.; Kwaiser, M.M.; Major, M.G.; Coble, C.; Wisner, K.; Koceja, D.; Martinez Kercher, V.M.; Kercher, K.A. Co-Design with Rural Adolescents to Inform a School-Based Physical Activity and Social Media Literacy Intervention: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101501

Watkins JM, Goss JM, Schigur AP, Kwaiser MM, Major MG, Coble C, Wisner K, Koceja D, Martinez Kercher VM, Kercher KA. Co-Design with Rural Adolescents to Inform a School-Based Physical Activity and Social Media Literacy Intervention: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101501

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatkins, Janette M., Janelle M. Goss, Autumn P. Schigur, Megan M. Kwaiser, McKenna G. Major, Cassandra Coble, Krista Wisner, David Koceja, Vanessa M. Martinez Kercher, and Kyle A. Kercher. 2025. "Co-Design with Rural Adolescents to Inform a School-Based Physical Activity and Social Media Literacy Intervention: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101501

APA StyleWatkins, J. M., Goss, J. M., Schigur, A. P., Kwaiser, M. M., Major, M. G., Coble, C., Wisner, K., Koceja, D., Martinez Kercher, V. M., & Kercher, K. A. (2025). Co-Design with Rural Adolescents to Inform a School-Based Physical Activity and Social Media Literacy Intervention: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101501