Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to summarize the ICF foci, looking beyond body structures and function, and to analyze who has been assessed in research about adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with CP in the phase of transition to adulthood. Method: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases were searched using terms related to cerebral palsy, adolescents/young adults, health development, participation, and independence. Studies including youth with CP (13–30 years old) published in English from 2014 to 2021 were considered. The methods of assessment reported in the included studies were used to identify the ICF foci and who was assessed. Results: In this study, 86 studies were reviewed. The main ICF foci are activity and participation (51% of the studies), personal factors (23%), ICF not covered (14%), ICF not defined (9%), with environmental factors being the least focused ICF component (3%). Most studies assessed AYAs directly (49% of studies). Conclusions: Activity- and participation-related constructs are the leading research focus of studies, and more attention is needed concerning environmental factors. AYAs are the main source of information, and the perspectives of other key figures are also being valued. To bridge the gap between child and adult health care, a broader view of health development and approaches to explore AYA developmental issues must be taken.

1. Introduction

In 2001, the World Health Organization published the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) with a framework for health that highlights a network of components that influence the functional status of all individuals. Moving beyond the impairments in body structure and function (BSF) traditionally addressed under a biomedical standpoint, components of activity and participation (AP), personal factors (PFs), and environmental factors (EFs) have achieved recognition under this holistic view of health [1]. Additionally, the Life Course Health Development concepts (LCHD) proposed by Halfon et al. (2014) [2] expand our perspective on health development, stating that health is a result of continuous interactions between the person and their environment. On-time experiences for this life stage are important for well-being, as well as for ensuring that the person’s voice is heard, thus grounding the development of the necessary supports and opportunities throughout their life course.

These biopsychosocial concepts encourage us to stop thinking of disabilities as just a biological or medical phenomenon ‘within the person’ and encourage us to think also about the impact of the impairments on a person’s functioning and life experience in general [2,3]. In this sense, over the years, the delivery of healthcare has evolved from a paternalistic, provider-driven, and disease-focused approach towards one of person-centered care, which puts the client in the center, engages them in decision making, develops their knowledge, and fosters self-care behavior [4,5,6].

Looking to the key developmental stages of life, research focusing on understanding the transition to adulthood of adolescents and young adults with chronic child-onset health conditions such as cerebral palsy (CP) [7] shows that the inadequate or limited healthcare services offered during childhood and adolescence may have a negative impact later on the lives of adults with CP [8], or that they at least fail to promote optimal health in the next stages of life.

Quality of life (QoL) is one health indicator that provides a broad picture of a person’s perception of life in several aspects [9] during their development. The childhood QoL level has been reported as a consistent predictor of QoL in adolescence [10]. For young adults with CP and more severe impairments, despite the increase in the QoL in social relationships, psychological well-being can decrease over the years [11], which can impact their health development in adult life.

With this in mind, supporting the development of other demands and capabilities related to adulthood, such as self-confidence, maintaining relationships, having a job, and independent living, are important aspects to be addressed in health care [12,13]; however, these elements are often a neglected aspect of the care delivered to young people with CP in the phase of transitioning to adulthood [14].

Research that has provided a voice to youths with CP reveals that they need more support to receive and seek information regarding transitioning to adulthood and overcoming environmental barriers, and they highlighted the desire for more strategies to promote real-life experiences related to adult life through their development [15,16]. Youth with CP also reinforce that participation is a key component of healthy living, and skills such as the self-management of their own health and self-advocacy should also be part of the care delivered to them; whereas skills such as fine and gross motor functions may have less importance, except if these functions directly impact their ability to participate [17].

However, impairments in BSF frequently are the main, if not the only, focus of interventions [18,19] aiming to improve the overall health [3] of individuals with CP. A literature review about interventions for children with CP outlined the lack of approaches focusing on aspects beyond BSF [20], which may lead clinicians to miss the opportunity to include other key aspects to improve the health of people with CP in their plan of care. To change this, instead of primarily targeting the achievement of abilities for functional skills, service providers are being challenged to expand their focus and promote rehabilitation strategies to improve the daily living capacities that are important to the person [17].

Under this approach, there is less emphasis on promoting typical development or ‘normal’ patterns, and more focus on finding solutions to enable AYAs to be autonomous and functional in activities which are meaningful to them, even in the face of the significant limitations of BSF, and even if they do things differently from typical peers [3].

Thus, healthcare professionals are encouraged to consider all of the ICF components as equally important entry points to promote the health of people with disabilities [21]. In this scenario, a broad exploration of the recent literature can contribute to identifying research patterns that need to change for the knowledge in this field to be expanded and support practice. Thus, we aimed to conduct a scoping review to summarize the ICF foci, to look beyond body structures and function, and to analyze who has been assessed in research about adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with CP in the phase of transitioning to adulthood. We specifically targeted research exploring health development, independence, and participation. Results from this review can indicate research gaps and guide future research and clinical practice on matters that need to be further addressed, thus contributing to improvements in the health development of young people with CP during the transition to adult life.

2. Materials and Methods

This review is registered at OSF Registries and can be found at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/J7XWZ (accessed on 14 May 2024). As a literature review, this scoping review does not require ethical committee approval. This review summarizes evidence published from 2014 to 2021, the last update being performed in February 2022. All the methodological steps for scoping reviews proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) [22] were followed. The PRISMA checklist for scoping reviews [23] is presented in Supplementary Information S1.

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

To present our research question in a structured manner, we used the ECLIPSE framework proposed by Wildridge and Bell (2002) [24]. Different from the PICO framework, which could be more useful for reviews focusing on clinical practice questions, the ECLIPSE framework (E: expectations, C: client group, L: location, I: impact, P: professionals, SE: service to deliver information) aims to assist searches for health planning and information management. Thus, our research question was as follows: Based on the published literature (P) between 2014 and 2021 (L), and looking beyond ICF body structure and function (E), which issues are emphasized and who was assessed (I) regarding the global health development, participation, or independence (SE) of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy (C)?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

Considering that, during adolescence and young adulthood, youth are transitioning to adult life and developing globally as unique persons, the following five key areas of interest were defined for the literature search based on our focus of interest and the general outcomes expected in adult life: cerebral palsy, adolescents/young adults, health development, participation, and independence. Librarians with experience in health sciences were consulted to guide the structure of the search strategy and provide useful databases to be searched. The search strategy defined was adapted according to each database, and a complete example can be seen in Supplementary Information S2. Through the OVID interface, we searched Medline, EMBASE, and PsycINFO, and, through the EBSCOhost, we searched CINAHL, limiting the articles to those published between 2014 and 2021 in the English language.

2.3. Study Selection

The Covidence systematic review software [25] was used to manage the review process. In applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, two independent reviewers (CASS and ACC or JVDK) screened all of the titles and abstracts. A third reviewer analyzed the disagreements (PR or ACC), and the first author (ACC) reviewed the full text and extracted data from the included papers. The criteria established were as follows in Table 1:

Table 1.

List of inclusion and exclusion criteria considered during the selection process.

2.4. Charting the Data

From the included studies, we extracted the first author name, publication year, first author country, title, the study aims, study type according to the authors’ description, participant characteristics (study groups, age, the CP participants’ Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) [26], Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) [27], Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) [28], Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS) [29], and Visual Function Classification System (VFCS) [30] levels), the assessment method, and who was assessed as described in the study’s methodology.

2.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Based on the methods of assessment used in each study (e.g., the scale or other method used to measure the study’s main outcome of interest) and its constructs, we linked the findings to the most appropriate ICF domain in order to understand the research focus. For this, we followed the ICF linking rules proposed by Cieza et al. (2002; 2019) [31,32]. The ICF universe can encompass various constructs assessed by most tools or assessment methods; however, the ICF components and categories cannot be broad or specific enough to cover all of the possible constructs being assessed in the studies. Thus, some constructs needed to be linked as ‘ICF—not covered’ (ICF-NC) when the meaning of the construct is not covered by any ICF component (e.g., quality of life) [32]. In cases where the construct’s meaning does not clearly belong to any ICF category, it could be linked as ‘ICF—not defined’ (ICF-ND) [32].

In addition, during the ICF linking process, we consulted the List of Pediatric Assessment Tools Categorized by ICF Model proposed by the American Physical Therapy Association [33], and, for tools that were not on this list, we consulted the Toolbox proposed by Schiariti et al. (2017) [34], the Rehabilitation Measures Database [35], or we searched constructs of the variables of interest using the ICF browser on the WHO ICF website [36].

The first author completed the first linking of all assessment methods, another author (ACC) independently checked the categorization, possible disagreements were solved via a consensus meeting (CASS and ACC), and all authors reviewed the final linking. To analyze who was assessed in the studies, we considered from who the studie’s variables were collected from, considering who completed the questionnaires or other outcomes of interest according to each author’s description in the methods.

3. Results

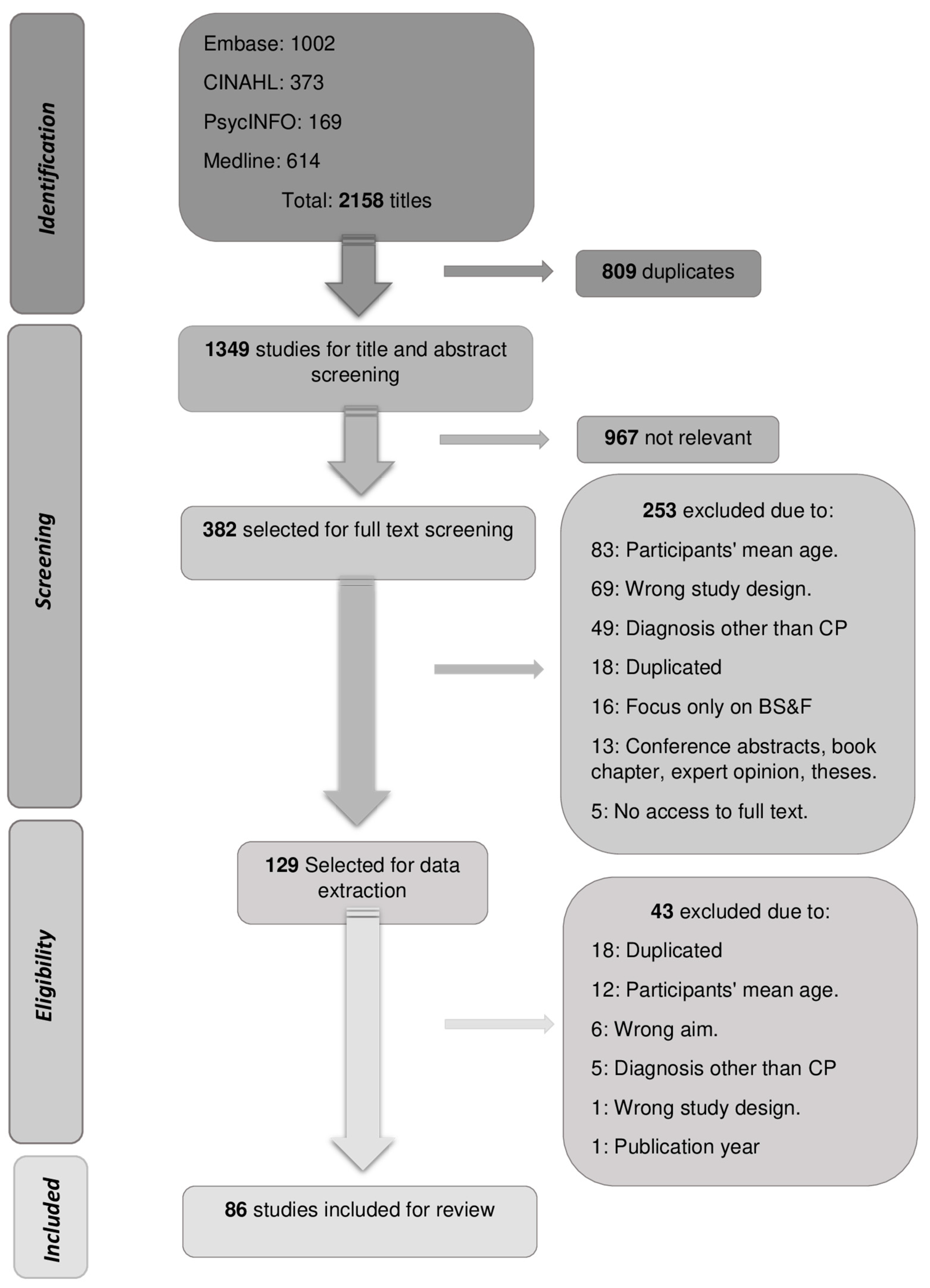

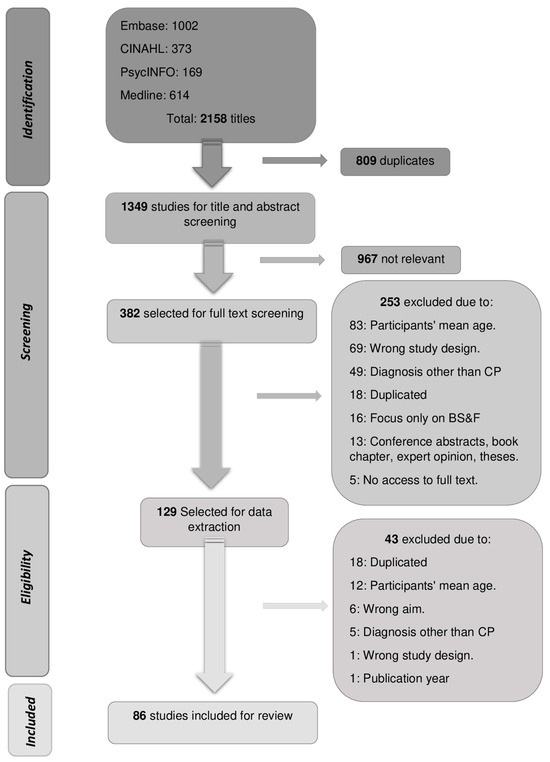

Studies published between January 2014 and December 2021 were retrieved from the databases, with the last search being updated in February 2022. After the study selection, 86 studies were included in this review for data summarization. The complete selection process can be seen in the PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart with the study selection process.

3.1. Studies Characteristics

Within the time reviewed, an average of 10 studies (SD ± 3.6) were published each year addressing the general health development, independence, or participation of young people with CP between 13 and 30 years of age. Despite including studies from 22 countries, high-income countries were the main source of publications in this field, of which the most frequently included were the United States of America (N= 17 studies), the Netherlands (N = 15), Canada (N = 13), Australia (n = 8), and the United Kingdom (N = 6). Among low- and middle-income countries, Brazil and South Africa were the most frequently represented, with three studies each.

Excluding the review studies, which comprise a diverse number of participants, our scoping review summarizes data from approximately 52,500 individuals, of whom around 43,570 have CP. Only the study by Liljenquist et al. (2018) [37] collected data from 35,290 individuals with CP. Furthermore, 42 studies focused on adolescents (with the mean age between 13–17 years) and 33 studies focused on young adults (mean age between 18–30 years), while 14 studies did not report the participants’ mean age, only stating that the age range was between 13 and 30 years.

The majority of studies did not have a comparison or control group (N = 60), focusing only on AYAs with CP. There was not a specific focus on any CP functional profile, with a relatively balanced representation of all manual, gross motor, and communication functional levels. The GMFCS was the classification system most frequently used (N = 63), followed by the MACS (N = 17) and CFCS (N = 8); only seven studies used all three of these common classification systems. No study used all five classification systems (GMFCS, MACS, CFCS, EDACS, VFCS) to characterize their population, and eighteen studies did not use any.

A wide range of methodologies was used across the studies, including observational, integrative knowledge translation, retrospective, randomized controlled trials, and others. Qualitative studies (N = 27) and longitudinal or cross-sectional studies (N = 15 each) were the most frequent methods used. In qualitative studies, interviews with open-ended questions and focus groups were the most common assessment method used. Supplementary Information S3 summarizes the included studies’ characteristics.

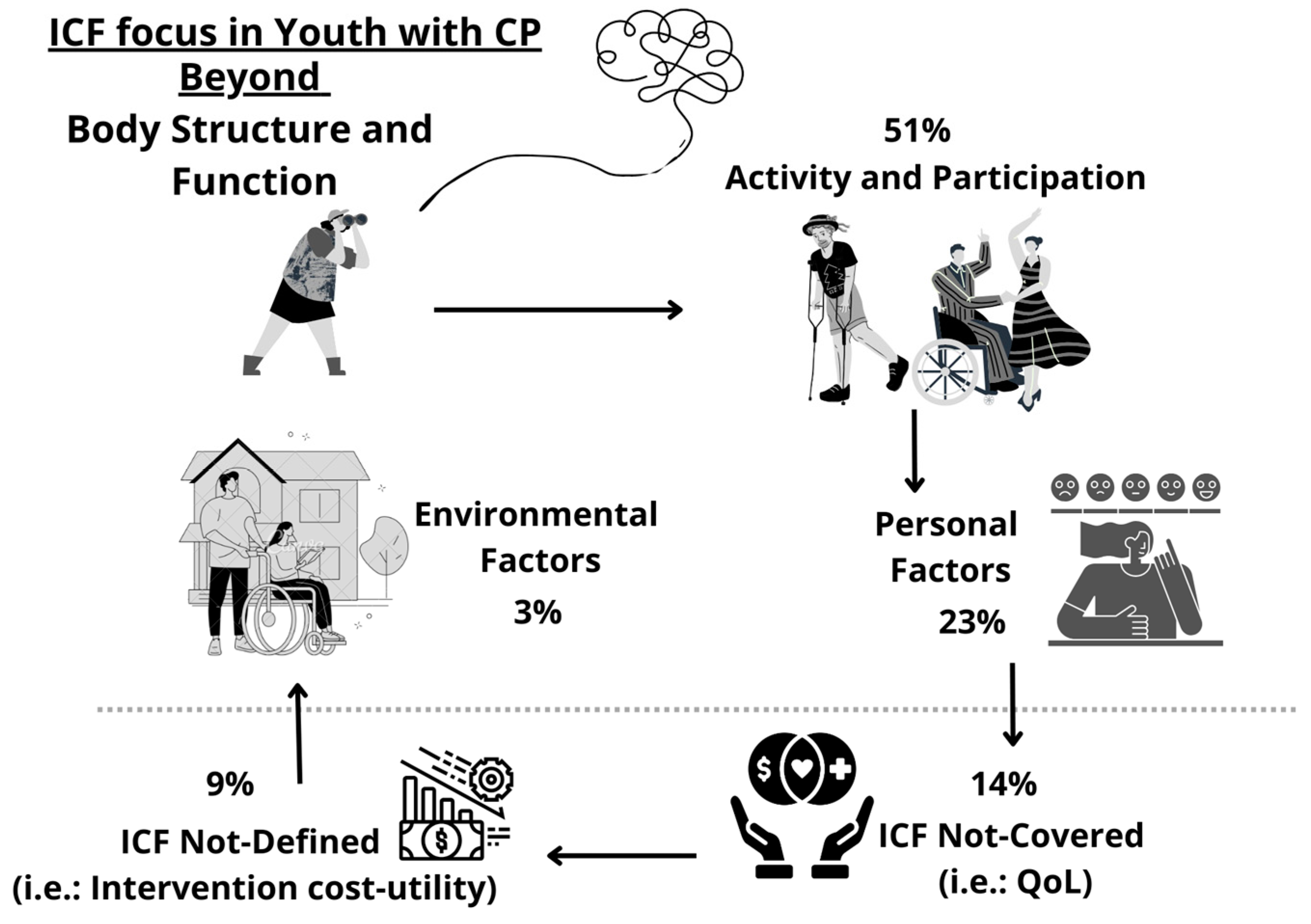

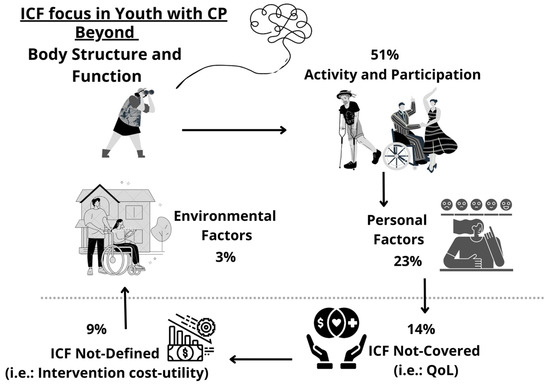

3.2. ICF Foci beyond BSF

Most studies did not specifically mention or organize their methods of assessment according to the ICF components. When categorizing the outcome measures based on the ICF components, among the eighty-six included studies, only five studies [38,39,40,41,42] included assessments comprising all other ICF components (AP, PFs, and EFs), and twenty-eight included more than one of these ICF components, thus assessing activity- and/or participation-related outcomes in combination with PFs and/or EFs in the same study.

Among the ICF components, the main focus of studies was related to AP (N = 31), with twenty studies assessing both AP, and six studies focusing mainly on activity-related constructs, such as functional classifications, mobility performance, and performance in activities of daily life. Participation-related outcomes were the main focus of five of the thirty-one studies. The Life-H was the most used tool when assessing participation.

The second ICF component most frequently focused on was PFs, with 24 studies choosing to assess only constructs related to this, such as AYAs’ age, gender, educational level, and perspectives about different issues, such as having a disability, socialization, and employment. The personal perspectives of AYAs and other persons, such as family members and health care providers, were explored, commonly using open-ended questions. The most frequently used tool to assess PFs was the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), usually answered by the parents, to screen the youth’s behaviour.When interviewing the AYAs, one of the tools used was the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSEE), aiming to explore the AYAs’ perceptions of self-efficacy.

The ICF component that was focused on the least were EFs, with only three studies [43,44,45] solely focusing on it and exploring issues related to healthcare services, such as care needs for AYAs transitioning to adulthood, and aspects related to parental distress. Together with other ICF components, studies explored other EFs, such as socioeconomic status, living situation, and aid needs. The assessment tools varied in this section, and the Craig Hospital Inventory of Environmental Factors (CHIEF), Pediatric Rehabilitation Intervention Measure of Engagement—Service Provider version (PRIME-SP), and the Measure of Processes of Care-20 (MPOC-20) were some of the tools used.

Excepting AP, PFs, and EFs, some studies explored constructs not covered (ICF-NC) or not defined (ICF-ND) among these main ICF domains. Thus, following the ICF linking rule used in this review, the outcomes of assessment in 15 studies were categorized as ICF-NC, as all of them assessed aspects related to quality of life (QoL). KIDSCREEN was the most used tool to assess QoL, chosen by six studies, followed by the SF-36, which was used in four studies.

Nine studies assessed constructs classified as ICF-ND, such as intervention cost-utility or summaries of database information. Looking beyond BSF, the distribution of the ICF foci of studies explored in this review is represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

ICF foci of studies addressing aspects related to health development, independence, or the participation of AYAs with CP. Legend: ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; CP: Cerebral Palsy; QoL: Quality of Life.

Despite not being the aim of this review, BSF is an important and frequent target in studies. Thus, we also took note of the methods used to assess these categories in the included studies. Among the 86 included studies, 59 did not assess any constructs related to BSF along with their primary outcomes. Only two studies assessed both components of body structure and body function along with AP, PFs, and/or EFs [46,47]. Specifically, body function was assessed in 25 studies, with constructs related to pain, fatigue, and cognition. No studies assessed only body structures together with other ICF components. These details are also included in Supplementary Information S3.

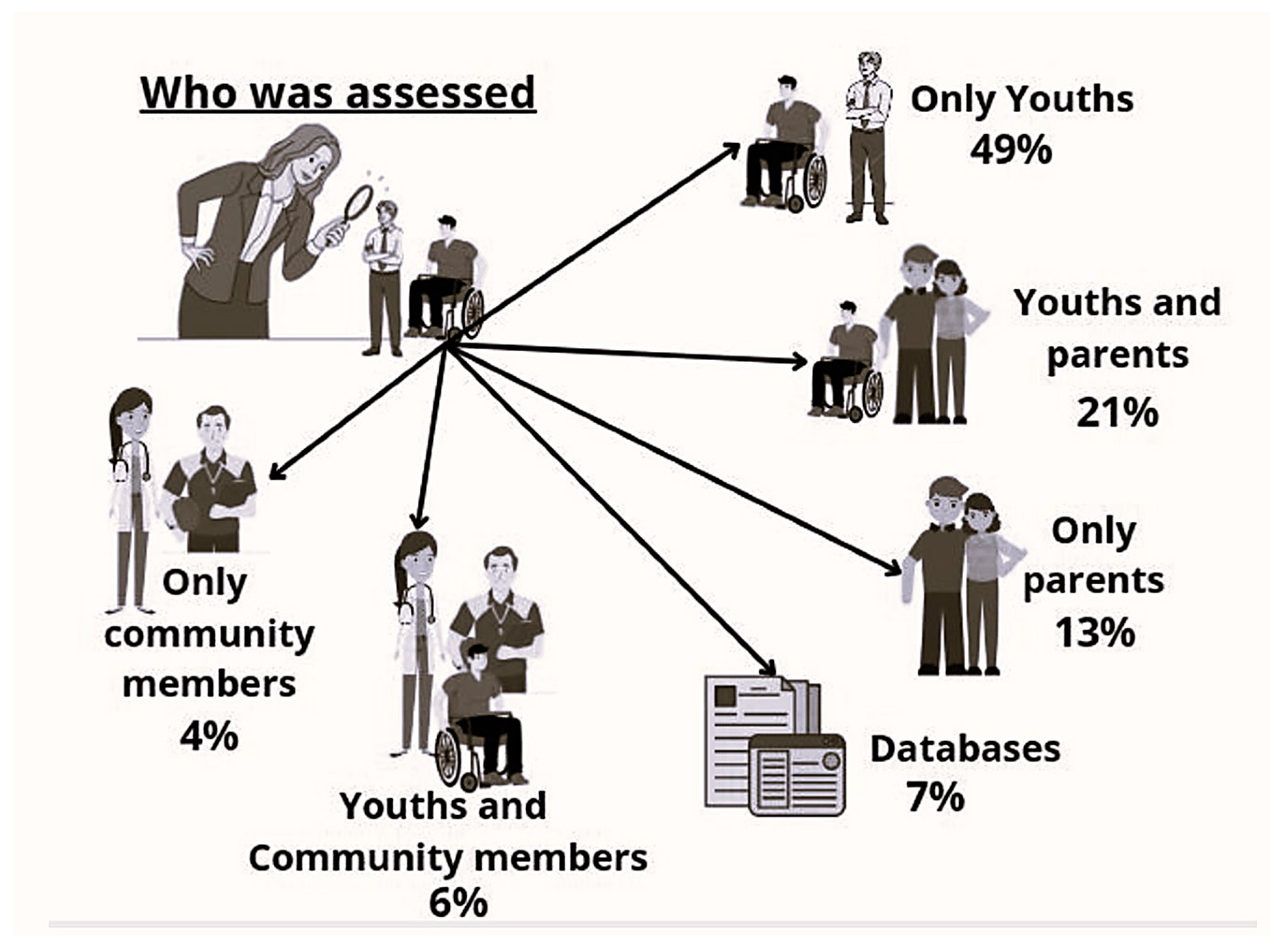

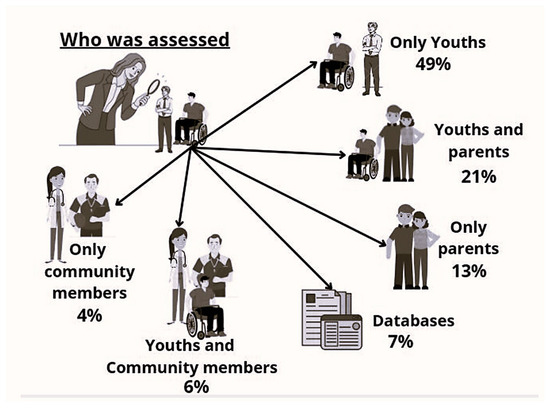

3.3. Who Was Assessed

Looking at who was assessed in the included studies, we found that 42 studies (49%) assessed AYAs directly, and information from the young people and family members were collectively obtained in 18 studies, with 11 studies capturing information exclusively from a family member. Expanding the source of information, nine studies collected data from other populations such as researchers, clinicians, and teachers, and, among those, five had also heard the young people’s voices. Databases or medical records were the sources of information in nine other studies, including the reviews. Figure 3 summarizes this information.

Figure 3.

Distribution of who was assessed in the studies about AYAs with CP.

4. Discussion

The transition to adult life for people with a child-onset disability can be complex, with many influencing factors needing to be better understood in order to eliminate the gap between the child and adult care received by this population. It is expected that, as youth with CP grow up, they will start to develop more independence, deal with issues that go beyond their disability, and participate more in diverse life situations. In our review, we summarized evidence to have a broader view of the current ICF focus, beyond BSF, in research exploring the health development, independence, or participation of AYAs with CP, and we also explored who is being assessed in these studies.

Looking at the research focus, the ICF component of activities, part of the AP component, was the most frequent area of interest in studies. These studies used tools or methods of assessment to analyze AYA capacities or performance in activities such as mobility [48], hand use [49], and activities of daily life [50]. Functional classification systems such as GMFCS, MACS, and CFCS are frequently used to categorize AYA capacity level or to analyze the relationship between the capacity level and other variables.

As these tools describe activity, they considerably steered the ICF linking process towards the ICF AP component. Of course, the high number of studies focusing on activities could be due to the fact that, as people with CP age, they tend to experience functional decline and other complications such as pain [51], and these aspects could impact their activity levels [52], which makes the understanding of their activity capacities or performance relevant.

Besides common barriers to participation in physical activities relating to the person’s capacity or ability to perform activities, other aspects such as social attitudes (EF), personal preferences (PF), and the confidence to do (PF) the activity are key facilitators to overcoming the barriers to participating in certain activities [53,54]. This highlights the importance of looking beyond factors related to BSF, including assessments or methods to analyze the contextual factors affecting activities that will facilitate better levels of participation for AYAs with CP.

In this sense, and also part of the ICF AP component, reviewed studies assessing participation focused on aspects such as the frequency of participation in everyday life [55], predictors (BSF and activity) of participation in domestic life, and interpersonal relationships [56]. We also explored aspects of participation relating to individual (PF) and environmental factors (EF) associated with changes in participation [57], satisfaction (PF) with the participation [58], and the association of modifiable childhood factors (PFs, EFs and BSF) on adolescents’ participation level [59].

As the transition to adulthood is a stage with significant environmental and personal changes, characteristics of activities and factors influencing participation may vary during this life period due to changes in functionality, the level of independence, and personal preferences. Thus, investigations concerning specific PFs affecting the transition process are crucial.

In our review, PFs were the second most addressed ICF component after AP, and common AYA personal variables such as age, gender, and educational level contributed to allocating PFs to this position during ICF linking. Key PFs such as AYA perspectives about the use of transition services [60], acceptance of their disability [61], and volition [62] were also explored.

It was observed that emotional support contributed to variations in the level of satisfaction with life and health status of young adults with CP [63]. PFs such as insecurity and sadness were mentioned as barriers influencing participation, while accepting the disability and having a positive attitude were facilitators according to adolescents’ perspectives [64]. Young adults with CP also emphasized the need for interventions (EF) that enable them to find their own way to perform everyday activities and be involved (AP), as this will contribute to building their personality (PF).

Along these lines, strategies aiming to enhance AYAs’ personal abilities to deal with environmental stressors or disappointments which are typical during the transition to adult life could be helpful in promoting their coping skills, empowering positive behavioural health [65], which could lead to better satisfaction with oneself, thus increasing confidence to participate and interdependent attitudes in different life situations. Facilitating this, professionals and family members could easily provide information (EF) about their disability (BSF) and future challenges (AP, PF, and EF) since the early stages of their development, enabling better levels of self-awareness and self-efficacy skills (PF) [66].

Is it possible to observe that, together with PFs, environmental factors will deeply influence our perception and development. The EFs comprise the physical, social, and attitudinal environments in which people live and conduct their lives [67]. Especially during transition, the diversity of environmental and personal changes occurring in a short period across ones lifespan brings challenges. In this sense, EFs such as accessible public places, inclusion policies for educational qualification, as well as social understandings of the capabilities of people with disabilities could be examples of easily modifiable EFs that could facilitate the transition of AYAs with disabilities. A recent review showed that EFs such as the type of school, family ecology, and parental stress were associated with participation levels for children and adolescents with CP at the beginning of their transition process [68]. Especially for young adults, governmental programs which intend to provide funding and connect people with disabilities to services in their community, such as doctors, jobs, sports, and social groups, could be a means to support a more independent, participative, and fulfilling adult life [69].

However, in our review and others concerning people with CP [19], EFs were the least focused on area among all ICF components. Among the included studies in our review, only three [43,44,45] used EFs as their exclusive research focus, and aimed to explore family members’ perspectives on healthcare needs [43,44], parental stress, and its impact on the family life [45]. Specifically, parental stress or mental health were assessed in five studies [41,45,59,70,71]. Common variables such as the parents’ educational level, family structure, and income were also frequently collected for characterization purposes, and could be used more frequently as possible influencing factors.

In the reviewed studies, family-related EFs are usually provided by a family member, but some studies explored EFs such as one’s housing situation, occupation, financial resources, and romantic relationships [17,72,73,74] through directly asking AYAs with CP. It is important to keep in mind that AYAs are at the center of the transition process, thus listening to them and asking specific questions about the different issues they experience is crucial. By letting AYAs express their own perspectives independently, their development of self-knowledge and autonomy (PF) is supported.

When using standardized tools, researchers and clinicians may face challenges in shifting the focus from parents to youth, as most of the existing tools were designed to collect information from a proxy. Expansions of these existing tools and the development of self-report versions are needed, as was done with the GMFCS [75]. It is important to think that, beyond the specific questions of standardized assessment tools, there is so much more to be explored that can help us fill the gaps in health development between childhood and adulthood.

Along these lines, our review explored who is being assessed in studies, and observed that most studies are listening primarily to the AYA. Several qualitative studies explored issues relating to health development, independence, or the participation of AYAs with CP. In these studies, the use of open-ended questions to explore young peoples’ experiences was the most common method used. Questions regarding the youths’ perspectives on their transition in health care [60], residential immersive life skill programs [76], participation [64], and lived experiences in several life areas [77] were some of the themes explored.

In studies focusing on understanding the life issues of AYAs with CP with cognitive impairments, the perspective of a person who knows the youth’s life, such as a family member, may be the only source of information possible, thus, youth’s voices need to be represented by them, as shown in Gray et al. (2021) [78].

It is important to consider that, in early adolescence, having the parents’ perspectives together with AYAs’ perspectives can be helpful in supporting them to feel more secure about the issue being asked. On the other hand, for AYAs with higher cognitive levels, the shift from asking a proxy to directly asking the youth about matters they experience is a need within research and clinical practice, as discrepancies could exist among adolescents and their relatives’ perspectives, who tend to rate adolescents’ issues more negatively [79]. These discrepancies can be natural during early and mid-adolescence, but may have more negative effects on adolescents’ wellbeing during late adolescence when they are seeking more autonomy and adapting to their health condition [80].

The transition between adolescence and adulthood involves more than just the AYA and their families, as it is expected that young people increasingly expand their connections with society during this period of life. Accordingly, some studies in our review collected information from the youth (PF) and community members (EF), such as healthcare providers, researchers, and teachers, thus providing a more complete contextual perspective.

From multiple viewpoints, Cleary and co-authors (2019) [81] explored barriers and facilitators to physical activity (AP) through listening to the adolescents, their parents, teachers, and therapists. Morris and colleagues (2018) [82] explored the factors affecting adolescents’ continuity in community-based physical activity (AP) through asking the adolescents, parents, and sports facilitators. In a knowledge translation study, perspectives from clinicians, researchers, parents, and AYAs were used to identify community-informed elements (EF) to guide the development of physical activity programs (AP) [83]. By also considering the point of view of these other figures, key information to support AYAs’ development can be collated more efficiently.

In order to evolve the understanding of facilitators and approaches to promote optimal health over the years, perhaps a successful transition between life stages could be expressed by an indicator such as QoL. QoL is not included among the ICF components, probably because it involves many related constructs that are difficult to separate clearly from each other. Additionally, the ICF creates an ‘objective’ picture of a person, but does not include subjective elements such as the self-reporting of feelings. Thus, on the ICF linking of our study, QoL was classified as ICF—not covered.

Nonetheless, from the eighty-six studies included in our review, fifteen studies assessed AYAs’ QoL, but only four studies [11,38,42,73] assessed QoL through asking the AYA in transition directly. In general, young adults with CP rated their QoL similar to the general population, but those with lower functional levels tended to score lower [73]. Similar results emerged from the study by Pagliano and co-authors (2021) [42], but, during in-depth interviews, signs of suffering due to isolation and relational difficulties were observed, aspects that had not emerged from the QoL questionnaires [42]. Thus, it is important to keep in mind that complex health issues require careful research planning so that they can be captured.

The family-centered care should be the basis of all approaches to care, but, wherever possible, it is necessary to start putting the person being cared for at the center of their own care, adopting a more person-centred approach. These processes should ideally be supported by a multidisciplinary team, who would be expected to see the AYA in transition beyond their disability, considering the several aspects that, as equally impactful as BSF-related factors, can influence a person’s development.

Based on the findings of this review, we recommend that researchers exploring health development, the independence, or the participation of AYAs with CP give greater attention to contextual factors, and, when possible, allow AYAs to speak for themselves about the issues they experience. Knowledge from this review can also support clinicians in expanding their assessment and interventional approaches when dealing with people with childhood-onset disabilities, as well as providing insights for policymakers to plan and execute new long-term policies for people with disabilities. These attitudes can contribute to bridging the gaps in knowledge, and to understanding and overcoming the barriers that interfere with the optimal health development of AYAs with CP between adolescence, adult life, and beyond.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review showed that, beyond BSF, studies from 2014 to 2021 exploring the health development, participation, or independence of AYAs with CP in the phase of transitioning into adulthood focused mostly on the ICF AP components, specifically on activity-related aspects. Fewer studies explored the influence of environmental factors. Most studies assessed AYAs directly mainly using qualitative studies. The perspectives of other key figures involved in their care and development were also considered. These findings emphasize the need for an expansion in the research focus towards multiple factors influencing AYAs’ health development, thus enabling clinicians to better understand and improve the care being offered to this population.

6. Study Limitations

No grey literature search was performed due to the high number of studies from the database search and the main focus on scientific papers only. Due to the nature of scoping reviews, the quality appraisal of included studies was not performed. The ICF linking was performed by one author; however, it was independentlychecked by at least two other authors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph21060670/s1. S1 PRISMA Checklist. PRISMA checklist for scoping reviews; S2 Appendix 1. Complete search strategy EMBASE example; S3 Appendix 2. Scoping review included studies characteristics, [84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126] are cited in Supplementary.

Author Contributions

C.A.S.S.: Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing. P.R.: Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing. J.v.d.K.: Formal Analysis, Writing. A.C.d.C.: Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Formal Analysis, Writing. All authors have approved the final version of the publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Government of Canada-Emerging Leaders in the Americas Program (ELAP), the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES-UFSCar/Brazil), and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP/Brazil–Process nº 2020/14627-9), which provided scholarships for the first author of this review.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge J.Y and L.B, Librarians from the Health Sciences Library at McMaster University, for their support in building the search string and selecting and managing the database used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- WHO—World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; WHO Library: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Halfon, N.; Larson, K.; Lu, M.; Tullis, E.; Russ, S. Lifecourse health development: Past, present and future. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargus-Adams, J.N.; Majnemer, A. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a framework for change: Revolutionizing rehabilitation. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathert, C.; Wyrwich, M.D.; Boren, S.A. Patient-centered care and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2013, 70, 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, S.J.; Cramm, J.M.; Nieboer, A.P. The importance of patient-centered care and co-creation of care for satisfaction with care and physical and social well-being of patients with multi-morbidity in the primary care setting. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, L.; Soeters, H.; Jokonya, M.; Kyendikuwa, A.; Hatane, L. Person-centred care: Shifting the power dynamic in the delivery of adolescent and youth-friendly health services. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, J.W.; Stewart, D.; Woodbury-Smith, M. Youth in transition: Care, health and development. Child Care Health Dev. 2011, 37, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colver, A.; Rapp, M.; Eisemann, N.; Ehlinger, V.; Thyen, U.; Dickinson, H.O.; Parkes, J.; Parkinson, K.; Nystrand, M.; Fauconnier, J.; et al. Self-reported quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Lancet 2015, 385, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagazgoïtia, N.V.D.; Ehlinger, V.; Duffaut, C.; Fauconnier, J.; Schmidt-Schuchert, S.; Thyen, U.; Himmelmann, K.; Marcelli, M.; Arnaud, C. Quality of Life in Young Adults With Cerebral Palsy: A Longitudinal Analysis of the SPARCLE Study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 733978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Imms, C.; Stewart, D.; Freeman, M.; Nguyen, T. A transactional framework for pediatric rehabilitation: Shifting the focus to situated contexts, transactional processes, and adaptive developmental outcomes. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Rezze, B.; Nguyen, T.; Mulvale, G.; Barr, N.G.; Longo, C.J.; Randall, G.E. A scoping review of evaluated interventions addressing developmental transitions for youth with mental health disorders. Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palisano, R.J.; Di Rezze, B.; Stewart, D.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Hlyva, O.; Freeman, M.; Nguyen, T.; Gorter, J.W. Life course health development of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagatell, N.; Chan, D.; Rauch, K.K.; Thorpe, D. “Thrust into adulthood”: Transition experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Health J. 2017, 10, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.; Stewart, D.; Cunningham, C.E.; Gorter, J.W. “If I had been given that information back then”: An interpretive description exploring the information needs of adults with cerebral palsy looking back on their transition to adulthood. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palisano, R.J.; Di Rezze, B.; Stewart, D.; Freeman, M.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Hlyva, O.; Wolfe, L.; Gorter, J.W. Promoting capacities for future adult roles and healthy living using a lifecourse health development approach. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2002–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M.A.S.; Ayupe, K.M.A.; Christovao, I.S.; Sousa Junior, R.R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Camargos, A.C.R.; Leite, H.R. Physical therapy in children with cerebral palsy in Brazil: A scoping review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, P.S.C.; Magalhães, E.D.D.; Sousa Junior, R.R.; Romeros, A.C.S.F.; Palisano, R.J.; Leite, H.R.; Rosenbaum, P. Development of children, adolescents, and young adults with cerebral palsy according to the ICF: A scoping review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2023, 5, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, I.; Mcintyre, S.; Morgan, C.; Campbell, L.; Dark, L.; Morton, N.; Stumbles, E.; Wilson, S.; Goldsmith, S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Gorter, J.W. The “F-words” in childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think. Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 38, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildridge, V.; Bell, L. How CLIP became ECLIPSE: A mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2002, 19, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Bartlett, D.; Livingston, M. GMFCS—E&R Gross Motor Function Classification System Expanded and Revised. 2007. Available online: https://www.canchild.ca/system/tenon/assets/attachments/000/000/058/original/GMFCS-ER_English.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Eliasson, A.-C.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Rösblad, B.; Beckung, E.; Arner, M.; Öhrvall, A.-M.; Rosenbaum, P. The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidecker, M.J.C.; Paneth, N.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Kent, R.D.; Lillie, J.; Eulenberg, J.B.; Chester, K., Jr.; Johnson, B.; Michalsen, L.; Evatt, M.; et al. Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellers, D.; Mandy, A.; Pennington, L.; Hankins, M.; Morris, C. Development and reliability of a system to classify the eating and drinking ability of people with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranello, G.; Signorini, S.; Tinelli, F.; Guzzetta, A.; Pagliano, E.; Rossi, A.; Foscan, M.; Tramacere, I.; Romeo, D.M.M.; Ricci, D.; et al. Visual Function Classification System for children with cerebral palsy: Development and validation. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieza, A.; Brockow, T.; Ewert, T.; Amman, E.; Kollerits, B.; Chatterji, S.; Üstün, T.B.; Stucki, G. Linking Health-Status Measurements to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. J. Rehabil. Med. 2002, 34, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, A.; Fayed, N.; Bickenbach, J.; Prodinger, B. Refinements of the ICF Linking Rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APTA. Academy of Pediatric Physical Therapy. Available online: https://pediatricapta.org/includes/fact-sheets/pdfs/FactSheet_ListofPediatricAssessmentToolsCategorizedbyICFModel_2013.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Schiariti, V.; Tatla, S.; Sauve, K.; O’Donnell, M. Toolbox of multiple-item measures aligning with the ICF Core Sets for children and youth with cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017, 21, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RMD-The Rehabilitation Measures Database-Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. 2022. Available online: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- WHO-World Health Organization. WHO-ICF Browser. Available online: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Liljenquist, K.; O’Neil, M.E.; Bjornson, K.F. Utilization of Physical Therapy Services During Transition for Young People With Cerebral Palsy: A Call for Improved Care Into Adulthood. Phys. Ther. 2018, 98, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaman, J.; Van Den Berg-Emons, H.; van Meeteren, J.; Twisk, J.; van Markus, F.; Stam, H.; van der Slot, W.; Roebroeck, M. A lifestyle intervention improves fatigue, mental health and social support among adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy: Focus on mediating effects. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, D.-W.; van Gorp, M.; van Wely, L.; Verheijden, J.; Voorman, J.; Wintels, S.; van der Cruijsen, J.; Ketelaar, M.; Dallmeijer, A.; Roebroeck, M.; et al. Participation in Social Roles of Adolescents With Cerebral Palsy: Exploring Accomplishment and Satisfaction. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2019, 1, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gorp, M.; Roebroeck, M.E.; van Eck, M.; Voorman, J.M.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Dallmeijer, A.J.; van Wely, L. Childhood factors predict participation of young adults with cerebral palsy in domestic life and interpersonal relationships: A prospective cohort study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3162–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, R.; Galea, C.; Muhit, M.; Heanoy, E.; Karim, T.; Badawi, N.; Khandaker, G. What predicts the proxy-reported health-related quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy in Bangladesh? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliano, E.; Casalino, T.; Mazzanti, S.; Bianchi, E.; Fazzi, E.; Picciolini, O.; Frigerio, A.; Rossi, A.; Gallino, F.; Villani, A.; et al. Being adults with cerebral palsy: Results of a multicenter Italian study on quality of life and participation. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 4543–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, J.A.; Conaway, M.R. Adolescents with cerebral palsy: Transitioning to adult health care services. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 53, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikwanha, T.M.; Chidhakwa, S.; Dangarembizi, N. Occupational therapy needs of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy in Zimbabwe: Caregivers’ perspectives. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 2015, 61, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guyard, A.; Michelsen, S.I.; Arnaud, C.; Fauconnier, J. Family adaptation to cerebral palsy in adolescents: A European multicenter study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 61, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capati, V.; Covert, S.Y.; Paleg, G. Stander use for an adolescent with cerebral palsy at GMFCS level V with hip and knee contractures. Assist. Technol. 2019, 32, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, L.K.; Farris, J.; Brockway, K.; Hannum, N.; Proctor, K. Promoting Self-exploration and Function Through an Individualized Power Mobility Training Program. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2015, 27, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennon, N.; Church, C.; Shrader, M.W.; Robinson, W.; Henley, J.; Salazar-Torres, J.d.J.; Niiler, T.; Miller, F. Mobility and gait in adults with cerebral palsy: Evaluating change from adolescence. Gait Posture 2021, 90, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusumoto, Y.; Takaki, K.; Matsuda, T.; Nitta, O. Relevant factors of self-care in children and adolescents with spastic cerebral palsy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira-Machado, L.; Azevedo-Santos, I.; DeSantana, J.M. Dance Improves Functionality and Psychosocial Adjustment in Cerebral Palsy. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 96, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, B.G.; Shah, S.; Coulson, N.; McLaughlin, J.; Logan, P.; Luke, R.; Avery, A.J. The impact of ageing on adults with cerebral palsy: The results of a national online survey. BJGP Open 2023, 7, BJGPO.2023.0028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abid, M.; Cherni, Y.; Batcho, C.S.; Traverse, E.; Lavoie, M.D.; Mercier, C. Facilitators and barriers to participation in physical activities in children and adolescents living with cerebral palsy: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 4322–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sienko, S. Understanding the factors that impact the participation in physical activity and recreation in young adults with cerebral palsy (CP). Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviram, R.; Khvorostianov, N.; Harries, N.; Bar-Haim, S. Perceived barriers and facilitators for increasing the physical activity of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy: A focus group study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 6649–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, S.I.; Flachs, E.M.; Damsgaard, M.T.; Parkes, J.; Parkinson, K.; Rapp, M.; Arnaud, C.; Nystrand, M.; Colver, A.; Fauconnier, J.; et al. European study of frequency of participation of adolescents with and without cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2014, 18, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gorp, M.; Van Wely, L.; Dallmeijer, A.J.; de Groot, V.; Ketelaar, M.; Roebroeck, M.E. Long-term course of difficulty in participation of individuals with cerebral palsy aged 16 to 34 years: A prospective cohort study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnemer, A.; Shikako-Thomas, K.; Schmitz, N.; Shevell, M.; Lach, L. Stability of leisure participation from school-age to adolescence in individuals with cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwellnus, H.; King, G.; Baldwin, P.; Keenan, S.; Hartman, L.R. A Solution-Focused Coaching Intervention with Children and Youth with Cerebral Palsy to Achieve Participation-Oriented Goals. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2020, 40, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.M.; Colver, A.; Dickinson, H.O.; Marcelli, M.; Michelsen, S.I.; Parkes, J.; Parkinson, K.; Rapp, M.; Arnaud, C.; Nystrand, M.; et al. Predictors of participation of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A European multi-centre longitudinal study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 36, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, E.M. Health Care Transition Experiences of Young Adults With Cerebral Palsy. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, e157–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normann, G.; Arntz Boisen, K.; Uldall, P.; Brødsgaard, A. Navigating being a young adult with cerebral palsy: A qualitative study. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2020, 34, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghanizadeh, M.; Khalafbeigi, M.; Akbarfahimi, M.; Yazdani, F.; Zareiyan, A. Exploring the contributing factors that influence the volition of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A directed content analysis. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 28, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienko, S.E. An exploratory study investigating the multidimensional factors impacting the health and well-being of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintels, S.C.; Smits, D.; van Wesel, F.; Verheijden, J.; Ketelaar, M.; the PERRIN PiP Study Group. How do adolescents with cerebral palsy participate? Learning from their personal experiences. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galambos, N.L.; Magill-Evans, J.; Darrah, J. Psychosocial maturity in the transition to adulthood for people with and without motor disabilities. Rehabil. Psychol. 2008, 53, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist, L.; Öhrvall, A.-M.; Himmelmann, K.; Peny-Dahlstrand, M. When I do, I become someone: Experiences of occupational performance in young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidert, M.; Hurst, R.; Miller, J.; Üstün, B. The role of environment in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kemp, J.; Ketelaar, M.; Gorter, J.W. Environmental factors associated with participation and its related concepts among children and youth with cerebral palsy: A rapid review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.Y.; Cleary, S.L.; Morgan, P.E. Participation experiences of young people with cerebral palsy in key life situations: A qualitative study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2024; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapp, M.; Eisemann, N.; Arnaud, C.; Ehlinger, V.; Fauconnier, J.; Marcelli, M.; Michelsen, S.I.; Nystrand, M.; Colver, A.; Thyen, U. Predictors of parent-reported quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A longitudinal study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 62, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentenac, M.; Rapp, M.; Ehlinger, V.; Colver, A.; Thyen, U.; Arnaud, C. Disparity of child/parent-reported quality of life in cerebral palsy persists into adolescence. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alriksson-Schmidt, A.; Hägglund, G.; Rodby-Bousquet, E.; Westbom, L. Follow-up of individuals with cerebral palsy through the transition years and description of adult life: The Swedish experience. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 7, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, D.N.O.; Löwing, K.; Tedroff, K. Health-related quality of life, pain, and fatigue in young adults with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrader, M.W.; Church, C.; Lennon, N.; Shields, T.; Salazar-Torres, J.J.; Howard, J.J.; Miller, F. Well-Being of Ambulatory Adults With Cerebral Palsy: Education, Employment, and Physical Function of a Cohort Who Received Specialized Pediatric Care. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 732906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, D.; Gorter, J.W. GMFCS—E&R Self Report Questionnaire: For Young People Aged 12–18 Years. 2011. Available online: https://canchild.ca/system/tenon/assets/attachments/000/000/481/original/GMFCS_Family.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- King, G.; Hartman, L.R.; McPherson, A.C.; DeFinney, A.; Kehl, B.; Rudzik, A.; Morrison, A. Exploring the after-hours social experiences of youth with disabilities in residential immersive life skills programs: A photo elicitation study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 44, 3104–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanes, J.E.; Hlyva, O.; Rosenbaum, P.; Freeman, M.; Nguyen, T.; Palisano, R.J.; Gorter, J.W. Beyond stereotypes of cerebral palsy: Exploring the lived experiences of young Canadians. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.H.; Wylie, M.; Christensen, S.; Khan, A.; Williams, D.; Glader, L. Puberty and menarche in young females with cerebral palsy and intellectual disability: A qualitative study of caregivers’ experiences. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramstad, K.; Loge, J.H.; Jahnsen, R.; Diseth, T.H. Self-reported mental health in youth with cerebral palsy and associations to recurrent musculoskeletal pain. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butner, J.; Berg, C.A.; Osborn, P.; Butler, J.M.; Godri, C.; Fortenberry, K.T.; Barach, I.; Le, H.; Wiebe, D.J. Parent–adolescent discrepancies in adolescents’ competence and the balance of adolescent autonomy and adolescent and parent well-being in the context of Type 1 diabetes. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 835–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, S.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Dodd, K.J.; Shields, N. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity for children with cerebral palsy in special education. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.; Imms, C.; Kerr, C.; Adair, B. Sustained participation in community-based physical activity by adolescents with cerebral palsy: A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 41, 3043–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, J.W.; Galuppi, B.E.; Gulko, R.; Wright, M.; Godkin, E. Consensus Planning Toward a Community-Based Approach to Promote Physical Activity in Youth with Cerebral Palsy. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2017, 37, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoef, J.; Bramsen, I.; Miedema, H.; Stam, H.; Roebroeck, M.; Transition and Lifespan Research Group South West Netherlands. Development of work participation in young adults with cerebral palsy: A longitudinal study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 46, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Pazi, H.; Barzilay, Y.; Shoval, N. Can global positioning systems quantify participation in cerebral palsy? J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 823–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooijen, C.F.; Slaman, J.; Stam, H.J.; Roebroeck, M.E.; Berg-Emons, R.J.; Learn2Move Research Group. Inactive and sedentary lifestyles amongst ambulatory adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaman, J.; van den Berg-Emons, R.; Tan, S.; Russchen, H.; Meeteren, J.; Stam, H.; Roebroeck, M. Cost-utility of a lifestyle intervention in adolescents and young adults with spastic cerebral palsy. J. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 47, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuba, K.; Oddson, B.; Gauthier, A.; Young, N.L. Leisure-Time Physical Activity in adults with Cerebral Palsy. Disabil. Health J. 2015, 8, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, B.C.; Duffy, C.; Parkes, J. Service use and family-centred care in young people with severe cerebral palsy: A population-based, cross-sectional clinical survey. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 2324–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vles, G.F.; Hendriksen, R.G.; Hendriksen, J.G.; van Raak, E.P.; Soudant, D.; Vles, J.S.; Gavilanes, A.W. Quality of Life of Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Cross-Sectional KIDSCREEN study in the Southern part of the Netherlands. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaman, J.; Roebroeck, M.; Dallmijer, A.; Twisk, J.; Stam, H.; Berg-Emons, R.v.D.; Learn 2 Move Research Group. Can a lifestyle intervention programme improve physical behaviour among adolescents and young adults with spastic cerebral palsy? A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynan, A.; Goldbart, J.; Murray, J. A grounded theory of Internet and social media use by young people who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1559–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantjes, J.; Swartz, L.; Conchar, L.; Derman, W. When they call me cripple: A group of South African adolescents with cerebral palsy attending a special needs school talk about being disabled. Disabil. Soc. 2015, 30, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantjes, J.; Swartz, L.; Conchar, L.; Derman, W. Developing programmes to promote participation in sport among adolescents with disabilities: Perceptions expressed by a group of South African adolescents with cerebral palsy. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2015, 62, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björquist, E.; Nordmark, E.; Hallström, I. Living in transition—Experiences of health and well-being and the needs of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldoff, E.A.; Holtzclaw, B.J. Physical Activity Among Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: An Integrative Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, e105–e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Walstab, J.; Reid, S.M.; Davis, E.; Reddihough, D. Quality of life in young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eken, M.M.; Houdijk, H.; Doorenbosch, C.A.M.; Kiezebrink, F.E.M.; Bennekom, C.A.M.v.; Harlaar, J.; Dallmeijer, A.J. Relations between muscle endurance and subjectively reported fatigue, walking capacity, and participation in mildly affected adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conchar, L.; Bantjes, J.; Swartz, L.; Derman, W. Barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity: The experiences of a group of South African adolescents with cerebral palsy. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.E.; Robb, J.; Shearer, M.C. Transition from paediatric to adult health services in Scotland for young people with cerebral palsy. J. Child Health Care 2016, 20, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumford, L.; Chau, T. Application of an access technology delivery protocol to two children with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2016, 11, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monbaliu, E.; De Cock, P.; Mailleux, L.; Dan, B.; Feys, H. The relationship of dystonia and choreoathetosis with activity, participation and quality of life in children and youth with dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017, 21, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.O.; De Souza, L.H. Problematic clinical features of children and adults with cerebral palsy who use electric powered indoor/outdoor wheelchairs: A cross-sectional study. Assist. Technol. 2017, 29, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, A.-P.; Tessier, R.; Nadeau, L. Sociometric status and the attribution of intentions in a sample of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caron, J.G.; Light, J. Social media experiences of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy who use augmentative and alternative communication. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2017, 19, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldoff, E.A. Parental perspectives on physical activity of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. J. Res. Nurs. 2017, 22, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Markowska, M.; Śliwiński, Z.; Pogorzelska, J.A. Quality of life in children and young people with tetraplegic cerebral palsy. Med. Stud./Stud. Med. 2018, 34, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Schwellnus, H.; Keenan, S.; Chiarello, L.A. Youth Engagement in Pediatric Rehabilitation: Service Providers’ Perceptions in a Real-Time Study of Solution-Focused Coaching for Participation Goals. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2018, 38, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherian, S.; Davies, C. Multiple stakeholder perceptions of assistive technology for individuals with cerebral palsy in New Zealand. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2018, 13, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.; Stewart, D.; Cunningham, C.E.; Gorter, J.W. Information needs of young people with cerebral palsy and their families during the transition to adulthood: A scoping review. J. Transit. Med. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burak, M.; Kavlak, E. Investigation of the relationship between quality of life, activity participation and environmental factors in adolescents with cerebral palsy. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 45, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, D.N.O.; Löwing, K.; Hjalmarsson, E.; Tedroff, K. Exploring social participation in young adults with cerebral palsy. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R.; Muhit, M.; Heanoy, E.; Karim, T.; Badawi, N.; Akhter, R.; Khandaker, G. Health-related quality of life and mental health of adolescents with cerebral palsy in rural Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remijn, L.; van den Engel-Hoek, L.; Satink, T.; de Swart, B.J.M.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G. “Everyone sees you sitting there struggling with your food”: Experiences of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1898–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.B.; Shikako-Thomas, K.; Cardoso, R.; Simões Matsukura, T. Social participation: The perspectives of adolescents with cerebral palsy and their mothers. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 67, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, E.; Raghavendra, P.; McMillan, J.M.; Gunson, J.S. Exploring participation experiences of youth who use AAC in social media settings: Impact of an e-mentoring intervention. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2019, 35, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalón, E.G.G.; Merrick, H.; Colver, A.; Linden, M. Transition Collaborative Group; Transition Collaborative Group. Did previous involvement in research affect recruitment of young people with cerebral palsy to a longitudinal study of transitional health care? BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.K.; van Gorp, M.; van Wely, L.; Ketelaar, M.; Hilberink, S.R.; Roebroeck, M.E.; Roebroeck, M.E.; Tan, S.S.; van Meeteren, J.; van der Slot, W.; et al. Autonomy in participation in cerebral palsy from childhood to adulthood. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, K.B.; Choi, Y.; Sung, K.H.; Chung, C.Y.; Lee, K.M.; Kwon, S.-S.; Cho, G.H.; Park, M.S. Correlation between Accelerometer and Questionnaire-Based Assessment of Physical Activity in Patients with Cerebral Palsy. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2020, 12, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.; Colquitt, G.; Elliot, S.; Emter, M.; Li, L. Using participatory action research to examine barriers and facilitators to physical activity among rural adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3838–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, A.; Steinbok, P. Long term outcome of Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy for the management of childhood spasticity-functional improvement and complications. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2020, 36, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnsen, R.; Ramstad, K.; Myklebust, G.; Elkjaer, S.; Pripp, A.H.; Klevberg, G.L. Independence of young people with cerebral palsy during transition to adulthood: A population-based 3 year follow-up study. J. Transit. Med. 2020, 2, 20190002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R.; Wiley, K.; Muhit, M.; Heanoy, E.; Karim, T.; Badawi, N.; Khandaker, G. ‘Flower of the body’: Menstrual experiences and needs of young adolescent women with cerebral palsy in Bangladesh, and their mothers providing menstrual support. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towns, M.; Lindsay, S.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.; Mansfield, A.; Wright, F.V. Balance confidence and physical activity participation of independently ambulatory youth with cerebral palsy: An exploration of youths’ and parents’ perspectives. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 44, 2305–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feitosa, A.M.; Mancini, M.C.; Silvério, A.P.M.; Gordon, A.M.; Brandão, M.B. “Help Me to Improve my Own Priorities!”: A Feasibility Study of an Individualized Intensive Goal Training for Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2021, 41, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Lee, E.; Kim, Y.; Matthews, C.; Swanson-Kimani, E.; Davis, D.; Vogtle, L.; Rimmer, J.H. Leisure-time physical activity interventions for children and adults with cerebral palsy: A scoping review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).