Othering Older People’s Housing: Gaming Ageing to Support Future-Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Othering of Ageing

1.2. Play and Serious Gaming to Personalise Ageing

2. Materials and Methods

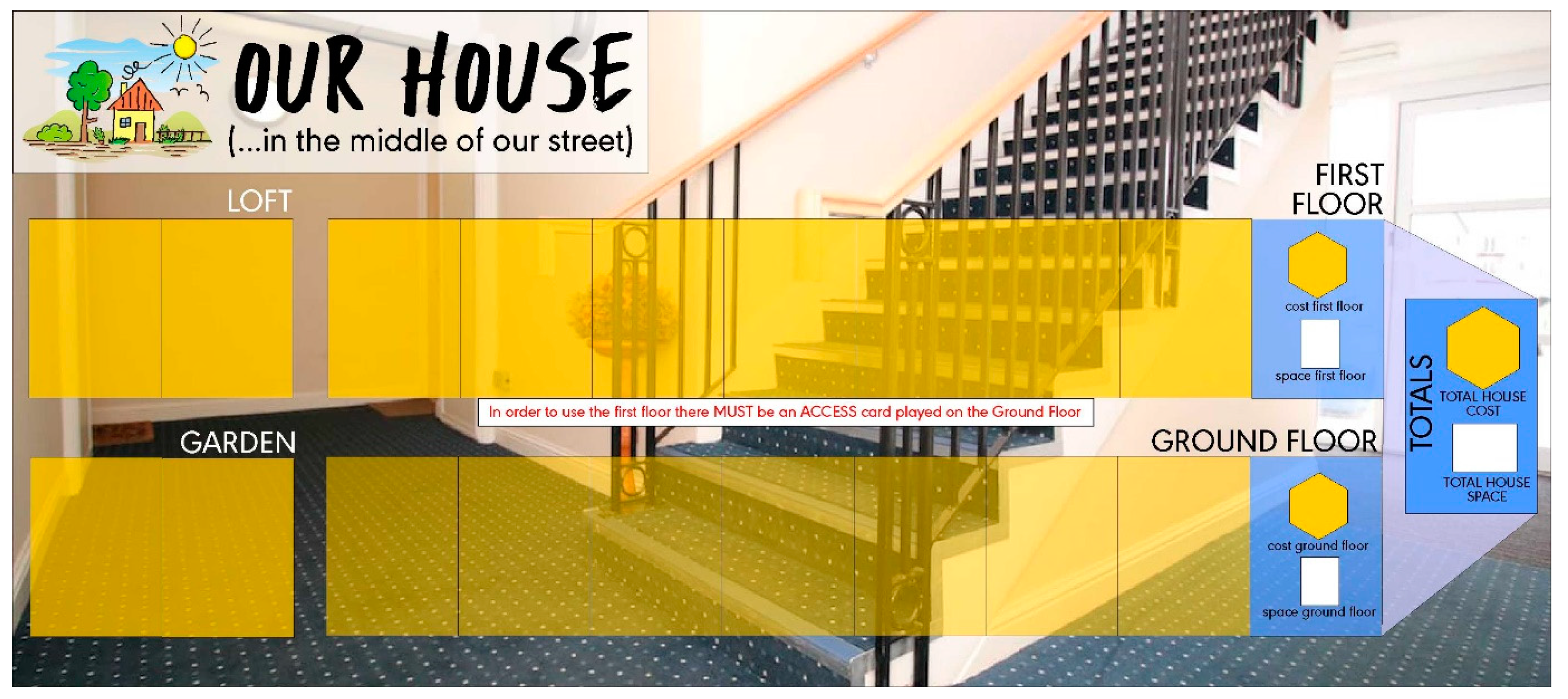

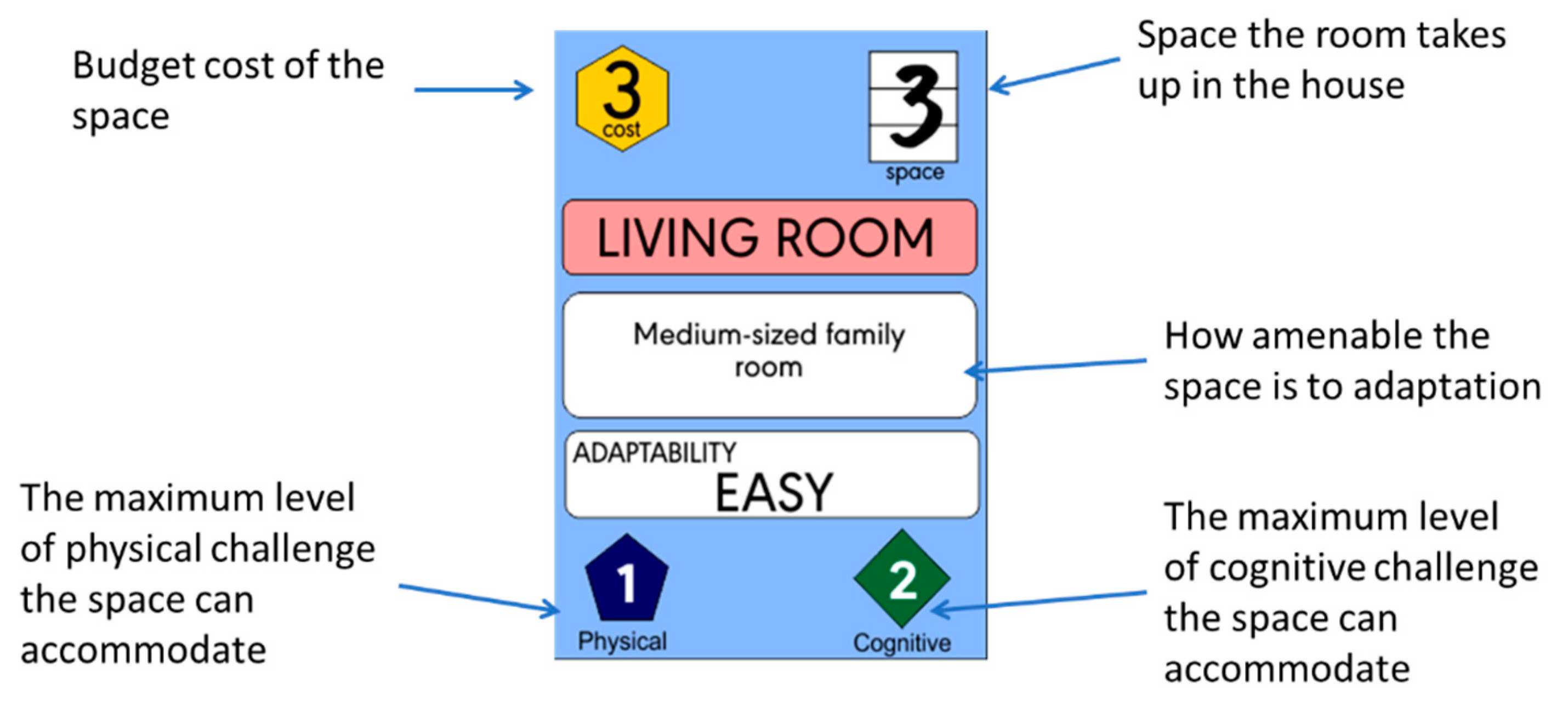

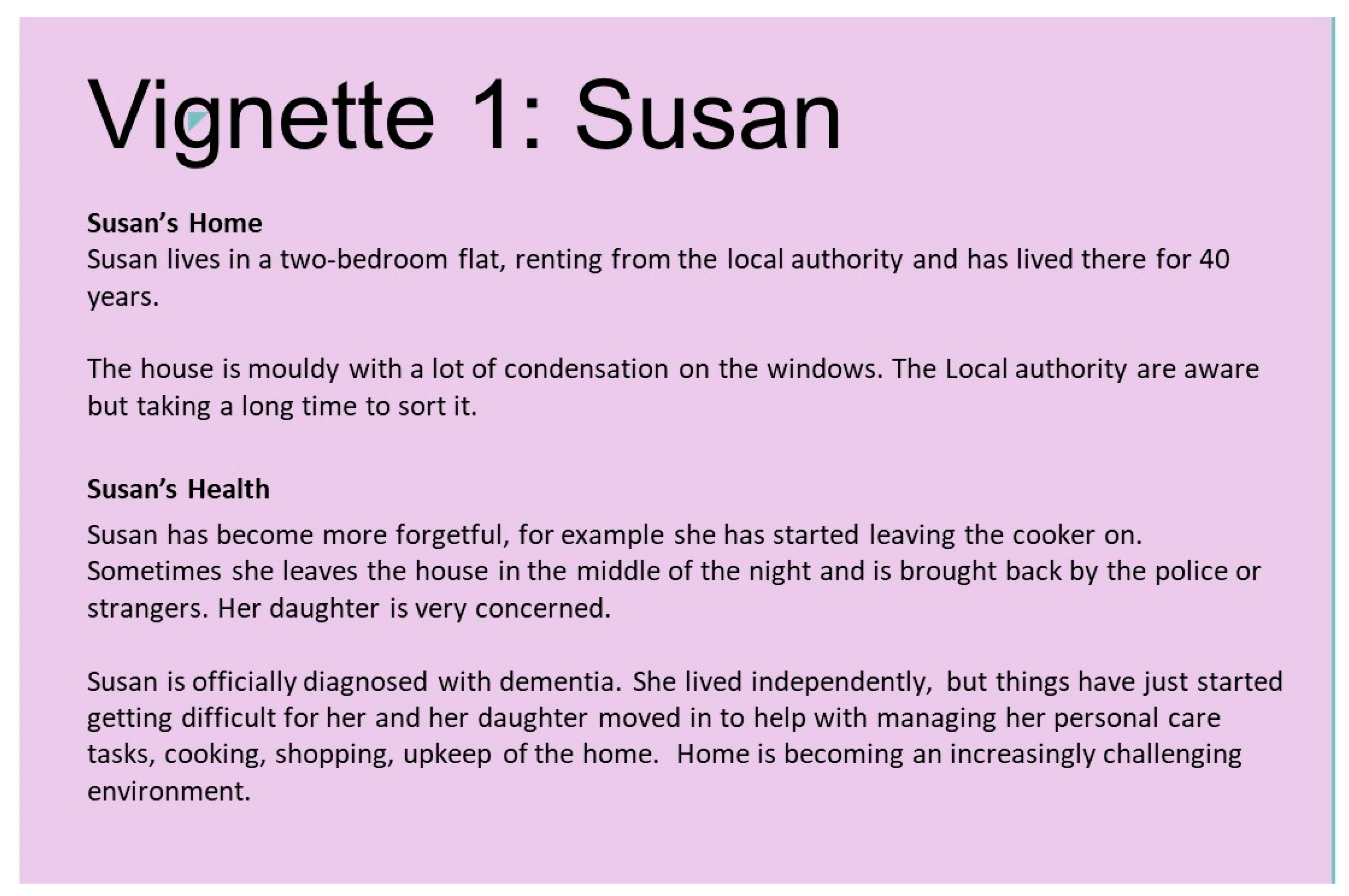

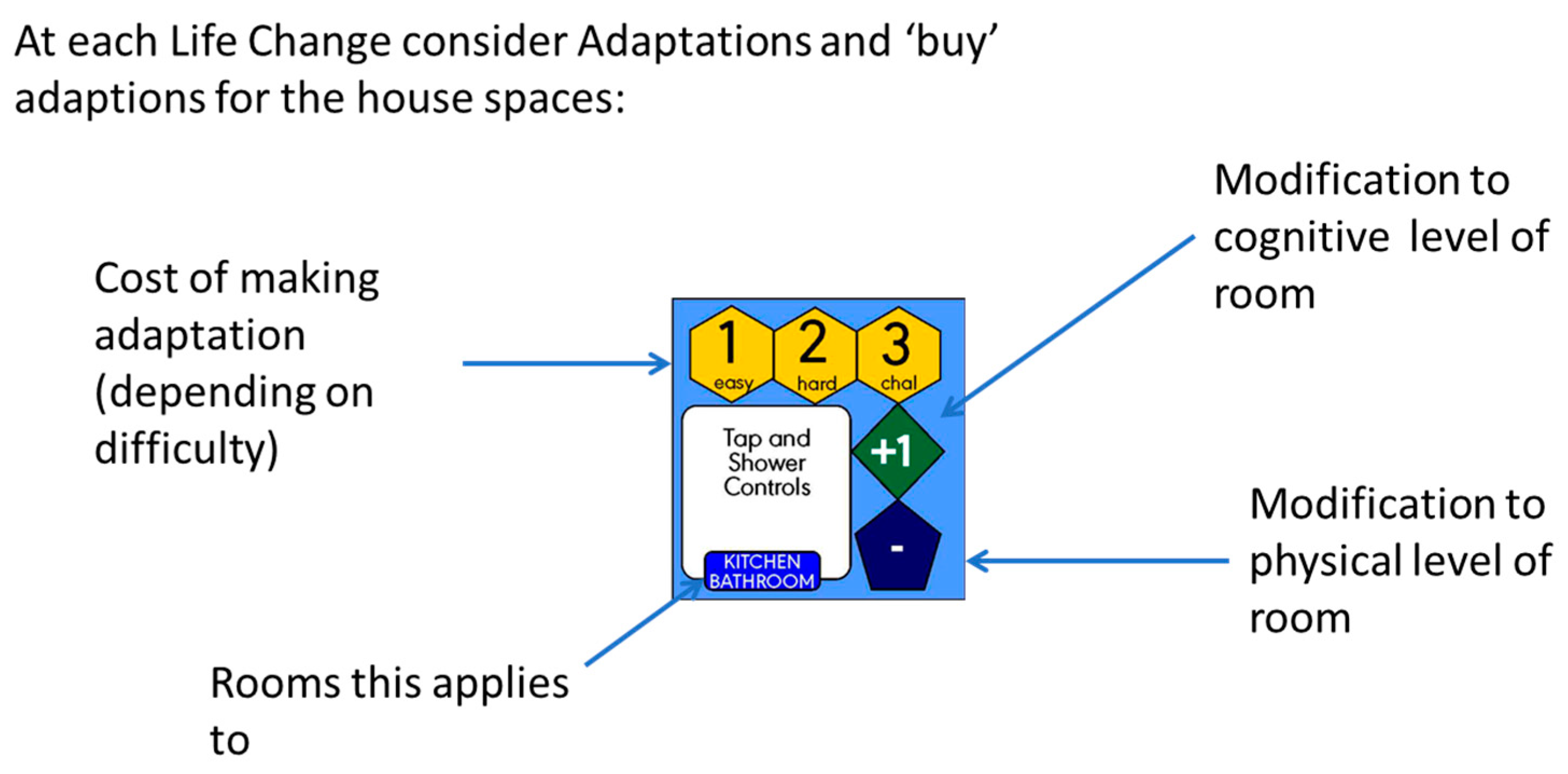

The Serious Game

3. Results

3.1. The ‘Othering’ of Ageing

But people don’t want to think about it. Especially when you start offending people and saying that an older person is aged 55 and older, and it’s like, but I’m not old.(R10, SGPT5, focus group)

I suppose if you start talking about ageing, at a younger age, it’s less sort of that whole kind of elephant in the room, people don’t want to talk about it. If it’s part of design, and it’s made to look nicer, then people aren’t going to be so, like, oh I’m not making my house an old person’s house.(R12, SGPT2, focus group)

I guess, maybe how you can see with age, it’s overwhelming, as well, like it’s new, adapting your house, and all the different options that will be there for you, it’s probably quite a lot for somebody to get into, and then funding streams, and things.(R6, SGPT5, focus group)

I think the main thing for us was, see just the budget, I think it kind of highlights just how important it is to have access to money… it sums up just how kind of a two-tier society you’ve got.(R6, SGPT2, focus group)

3.2. Personalising Ageing by Serious Gaming

It makes me think about my parents, now, and thinking, okay, their house is not currently fit for ageing well…. And that’s scary.(R5, SGPT6 focus group)

Well, am I going to have white, plastic grab-rails everywhere, is my home going to become ugly… I feel like it’s a hard sell, to people over the age of 55, 60, you know. I’m thinking of my own mum, she’s like, well I’m not an old person, you know, she’s only mid-60s.(R10, SGPT5, focus group)

I think I’ve just built Derek’s [in the vignette] whole life up. And I just find it, it’s just a really hard thing to sit and talk about, abstractedly, when you have experienced this yourself in your own family, and it isn’t a paper exercise, that’s quite hard.(R2, SGPT6, focus group)

Because life does happen, it does change. I speak from experience. My partner was diagnosed with MND, which I mean, that just turns your world on its head… And well, adaptations, that doesn’t even begin to cover what was needed.(R3, SGPT9, focus group)

All of a sudden you… start bandying around that people are old, you know, you’re an old person, you need to consider old people things, and it’s like, no, no I don’t, I’m perfectly fine… but it’s not a negative thing, it’s a positive thing, and it’s trying to make sure that we don’t get to, kind of, crisis point.(R11, SGPT5, focus group)

Everybody thinks of somebody who’s old is ten years older than them… So, I’ve just turned 50, so I don’t see myself as old, but you know, 60, and I still won’t see myself as old.(R1, SGPT5, focus group)

3.3. Serious Play and Ageing

Today’s visit brought home the importance of future proofing.(Aaron, SGPT1, feedback form)

But that’s all wrapped up with how people conceive ageing, isn’t it? And I think we need to change the conversation, so that people see ageing in a positive way, you know, the joke being, it’s better than the alternative. But, you know, it is about changing that, the whole conversation around ageing.(R11, SGPT5, focus group)

The exercise has made people to think about house as a place to get the most out of rather than as an asset to be passed on.(SGPT5, notes)

Does that still feel like a home, or is it a place that you’re surviving in.(R1, SGPT6, focus group)

I think it highlighted for me… working from the social housing side of things, how much easier it is for a tenant of a social landlord to get an adaptation. But actually, conversely, how difficult it is for someone living in private accommodation.(SGPT5, focus group)

This has prompted me to think more thoroughly about the ways a home can adversely impact an individual’s wellbeing… I will aim to promote this future-oriented perspective as I continue into my profession. I recommend continued collaboration between OT [occupational therapist] + housing officers in order to promote holistic wellbeing for the clients.(Erika, SGPT1, feedback form)

So, from a policing perspective, what would happen in Susan’s case… we would notify social services, and the housing, the social housing she was actually in, and notify them of the actual incident. And that will probably trigger conversations from a multiagency partnership approach to whether Susan’s accommodation is suitable for her, or if she was placing herself more at risk. Which, looking at it from this perspective now, and thinking of me being Susan, it’s totally against what I’ve been dealing with for the last 27 years.(R1, SGPT5, focus group)

Make allowance for future proofing before health starts to decline. Think about space standards and ease of adaptability. Look at own design guide to make more/all homes adaptive.(Henry, SGPT1 feedback from)

Find small aids that help me and complement my supported housing. Develop support package while waiting for a diagnosis. Create + develop (new) shared places, e.g., shared gardens.(Nelly, SGPT2, feedback form)

Thinking towards future house moves for various physical and cognitive problems. b: personalising projects and future end users. Using capital costs to reduce operational/maintenance costs. Embedding adaptability as a requirement at briefing stage.(Pierre, SGPT2, feedback form)

We do fixate about age, but we don’t focus as much about people’s health. And actually, things can happen to any of us, at any age… that suddenly means that we’ve got all of these physical barriers in our home. And I presume that we probably all know people that something has happened to them, whether they’ve had a stroke, or you know, and then overnight, the home is just not accessible. So, it’s maybe just taking that age, you know, assuming it’s all tied in with ageing, and actually, it’s just about being able to live healthy and independently, and to have a home that allows you to do that. And maybe that’s where the discussion needs to be, you know, around that. And it could be anybody in your household, it could be a child, it could be, you know, yourself.(R3, SGPT5, focus group)

3.4. The Challenges for Planning for the Future

And that is, you know, I guess, ideal solutions do exist, but in reality, they don’t, because people will always have some kind of constraint. Whether that’s a budgetary constraint on their own finances, or whether their grant applications don’t get accepted, or the type of property that they’re in isn’t conducive to adaptations, there’s always going to be some kind of compromise.(R10, SGPT5, focus group)

Well, I think it’s tricky with him, because he doesn’t have a diagnosis, so we’re not a hundred percent sure. At least with a diagnosis, you might have a bit of a clearer idea about what, if there is going to be further deterioration, what that means for your body, and what, then, future-proofing you might need.(R1, SGPT6, focus group)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Dyke, S. The othering of old age: Insights from Postcolonial studies. J. Aging Stud. 2016, 39, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søraa, R.A.; Manzi, F.; Kharas, M.W.; Marchetti, A.; Massaro, D.; Riva, G.; Serrano, J.A. Othering and deprioritizing older adults’ lives: Ageist discourses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, V. Inclusive Living: Ageing, adaptations and future-proofing homes. Build. Cities 2022, 3, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, V.; Gibb, K.; Wang, Y. The “fight” for adaptations: Exploring the drivers and barriers to implementing home and environment modifications that support healthy ageing. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, S.; Spann, A.; Borilovic, J.; de Witte, L.; Hawley, M. Understanding the care and support needs of older people: A scoping review and categorisation using the WHO international classification of functioning, disability and health framework (ICF). BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golant, S.M. Conceptualizing time and behavior in environmental gerontology: A pair of old issues deserving new thought. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffel, T.; Yarker, S.; Phillipson, C.; Lang, L.; Lewis, C.; Doran, P.; Goff, M. Locked down by inequality: Older people and the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1465–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golant, S.M. Aging in the Right Place; Health Professions Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bigonnesse, C. The Role of the Socio-Physical Environment on Aging in Place for Older Adults in Cohousing and Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crookall, D. Serious games, debriefing, and simulation/gaming as a discipline. Simul. Gaming 2010, 41, 898–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, V.; Ziegler, F.; Robertson, J.; Lovatt, M.; Phillips, J.; Porteus, J.; McIntyre, Z.; Rutherford, A.; Sizsmith, J.; Woolrych, R.; et al. Housing and ageing: Let’s get serious—“How do you plan for the future while addressing immediate chaos?”. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.K.; Martin, A.; White, J. Gamification and older adults: Opportunities for gamification to support health promotion initiatives for older adults in the context of COVID-19. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2023, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, R.N. Age-Ism: Another form of bigotry. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausknecht, S.; Low, L.-F.; O’Loughlin, K.; McNab, J.; Clemson, L. Older adults’ self-perceptions of aging and being older: A scoping review. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e524–e534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, T.N.; Larsen, L.; Solem, P.E. A conceptual analysis of ageism. Nord. Psychol. 2009, 61, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, L.; Padiero, M.; Santana, P. The twin faces of ageism, glorification and abjection: A content analysis of age advocacy in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Aging Stud. 2021, 57, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilleard, C. Aging as Otherness: Revisiting Simone de Beauvoir’s Old Age. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilleard, C.; Higgs, P. Aging without agency: Theorizing the fourth age’. Aging Ment Health 2010, 14, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuurman, B.; Lindenberg, J.; Huijg, J.M.; Achterberg, W.P.; Slaets, J.P.J. Expressions of self-ageism in four European countries: A comparative analysis of predictors across cultural contexts. Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 1589–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, C.; Howell, B.M.; Symons, K. How we talk about aging during a global pandemic matters: On ageist othering and aging ‘others’ talking back. Anthropol. Ageing 2020, 41, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, A.; Phillipson, C. Precarity and dementia. In Critical Dementia Studies: An Introduction; Ward, R., Sandberg, L.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global Report on Ageism. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240016866 (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Centre for Ageing Better. Ageism: What’s the Harm? 2023. Available online: https://ageing-better.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-02/Ageism-harms.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Cebola, M.M.J.; Rebelo dos Santos, N.; Dionisio, A. Worker-related ageism: A systematic review of empirical research. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 1882–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, H. Ageism and psychological well-being among older adults: A systematic review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 8, 23337214221087023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, M.; Chasteen, A.L.; Plaks, J.E.; Balasubramaniam, L. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the effects of negative age stereotypes and perceived age discrimination on older adults’ well-being. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1666–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greasley-Adams, C.; Robertson, J.; Gibson, G.; McCall, V. A Good Life in Later Years: A Co-Produced Research Project; Life Changes Trust: Glasgow, UK, 2017; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1893/26983 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Gullette, M.M. Aged by Culture; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. When the story’s over: Narrative foreclosure and the possibility of self-renewal. In Lines of Narrative; Andrews, M., Day Sclater, S., Squire, C., Treacher, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, J.; Carpentieri, J.D. Narrating future selves: Perspectives on ageing from a Scottish cohort born in 1936. Anthropol. Aging 2020, 41, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasmanová Marhánková, J.; Soares Moura, E. ‘What Can I Plan at This Age?’ Expectations Regarding Future and Planning in Older Age. Sociol. Res. Online 2023, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Auer, E.M.; Collmus, A.B.; Armstrong, M.B. Gamification science, its history and future: Definitions and a research agenda. Simul. Gaming 2018, 49, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agogué, M.; Levillain, K.; Hooge, S. Gamification of creativity: Exploring the usefulness of serious games for ideation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2015, 24, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbels, B.R. Gamification transformed: Gamification should deliver the best parts of game experiences, not just experiences of game parts. In Transforming Gaming and Computer Simulation Technologies Across Industries; Dubbels, B.R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, G.; Oliveira, T. Gamification and serious games: A literature meta-analysis and integrative model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Faatz, A.; Knüppe, L.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding the effectiveness of gamification in an industrial work process: An experimental approach. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2022, 28, 784–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopler, S.; Beil, D.; Putz-Egger, L.M. Cognitive learning outcomes of virtual vs. in-person gamified workshops: A pre-post survey experiment. In Proceedings of the 7th International GamiFIN Conference 2023, Lapland, Finland, 18–21 April 2023; Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3405/paper13.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Altmeyer, M.; Lessel, P.; Krüger, A. Investigating gamification for seniors aged 75+. In Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Hong Kong, China, 9–13 June 2018; Available online: https://www.dfki.de/fileadmin/user_upload/import/9808_p453-altmeyer.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- [DesHCA] Designing Homes for Healthy Cognitive Ageing. 2022. Available online: https://www.deshca.co.uk (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Pierce, M.; Cahill, S.; Grey, T.; Dyer, M. Research for Dementia and Home Design in Ireland Looking at New Build and Retro-fit Homes from a Universal Design Approach: Key Findings and Recommendations Report 2015. Dublin, Ireland. 2015. Available online: https://universaldesign.ie/uploads/publications/Research-for-Dementia-and-Home-Design-in-Ireland_2023-11-07-122820_snsu.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Bowes, A.; Dawson, A. Designing Environments for People with Dementia: A Systematic Literature Review; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, G.; Noel-Smith, J.; Palmer, L.; Quirke, M.; Wallace, K. R7 The Domestic Environment, in Environments for Ageing and Dementia Design Audit Tool; Dementia Services Development Centre, University of Stirling: Stirling, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-908063-37-3. Available online: https://www.dementia.stir.ac.uk/eaddat-getting-started (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- AECOM. Spon’s Architects’ and Builders’ Price Book 2024; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781032550084. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, V. Belonging across the lifetime: Time and self in Mass Observation accounts. Br. J. Sociol. 2018, 69, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCall, V.; Rutherford, A.C.; Bowes, A.; Jagannath, S.; Njoki, M.; Quirke, M.; Pemble, C.M.; Lovatt, M.; Davison, L.; Maginn, K.; et al. Othering Older People’s Housing: Gaming Ageing to Support Future-Planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030304

McCall V, Rutherford AC, Bowes A, Jagannath S, Njoki M, Quirke M, Pemble CM, Lovatt M, Davison L, Maginn K, et al. Othering Older People’s Housing: Gaming Ageing to Support Future-Planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(3):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030304

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCall, Vikki, Alasdair C. Rutherford, Alison Bowes, Sadhana Jagannath, Mary Njoki, Martin Quirke, Catherine M. Pemble, Melanie Lovatt, Lisa Davison, Katie Maginn, and et al. 2024. "Othering Older People’s Housing: Gaming Ageing to Support Future-Planning" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 3: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030304

APA StyleMcCall, V., Rutherford, A. C., Bowes, A., Jagannath, S., Njoki, M., Quirke, M., Pemble, C. M., Lovatt, M., Davison, L., Maginn, K., Scrutton, P., Pengelly, R., & Gibson, J. (2024). Othering Older People’s Housing: Gaming Ageing to Support Future-Planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(3), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030304