Abstract

Chronic high stress levels related to work impact the quality of life (QoL). Although physical activity improves QoL, it is not clear whether this life study habit could attenuate possible relationships between QoL and stress in public school teachers. The sample for this study was made up of 231 teachers from public schools. QoL was assessed using the Short-Form Health Survey and physical activity via Baecke’s questionnaire. A Likert scale assessed stress level perception. Poisson Regression analyzed the association between stress level and QoL domains adjusted for sex, age, and socioeconomic conditions (model 1). In model 2, physical activity level was inserted in addition to model 1. Seven out of eight domains of QoL, except the domain of pain, were associated with high levels of stress (all p < 0.05–model 1). However, in model 2, the associations of the high levels of stress with general health status (p = 0.052) and functional capacity (p = 0.081) domains of QoL were mitigated. Our results indicated that physical activity mitigated the relationship between higher levels of stress and lower perception of general health status and functional capacity domains in secondary public school teachers.

1. Introduction

Teaching is considered one of the most important professions around the world. Besides spending many hours per week in activities in the classroom, it is common for teachers to perform extracurricular activities (e.g., setting up and correcting exams and being school coordinators), which leads to a high workload [1,2,3]. Extracurricular activities are usually carried out during weekends, which decreases the time for recreational activities and family [4]. In addition, teachers report difficulty in decreasing their working hours due to their demands to improve the teaching quality and the expectations of society [5]. It should be highlighted that almost 90% of teachers in public schools reported an increase in overall hours over the past years [1]. Previous studies have demonstrated that a high workload decreases well-being and affects physical and mental health, such as an increase in stress levels [6,7,8].

Stress results from a hard situation that threatens homeostasis, which could cause a state of worry or mental tension. Stress can be understood as a normal reaction of the body when situations of danger or threat are experienced, causing the body to be in a state of alert [9]. The risk of stress and burnout related to work seems to increase according to the number of working hours [8]. Teachers with a high level of workload can present sleep problems and burnout and reported higher stress levels in different countries [10,11,12]. In a nationwide survey in Japan carried out from June to December 2018, it was observed that the high workload in public junior high school teachers was associated with higher levels of stress [13]. Burnout syndrome is generally considered professional exhaustion caused by excessive work demands [14,15,16]. In most cases, all body systems are affected by stress (e.g., cardiovascular, endocrine, nervous, and muscular systems) [14]. Thus, staying in a state of stress for a long time impacts the organism’s homeostasis and leads to several physical and mental illnesses, such as anxiety, depression, cardiovascular diseases, stomach ulcers, and sleep dysregulation, and impacts social interaction [14,15,16], which impact the quality of life (QoL).

Quality of life is the self-perception that human beings have of their own health, considering emotional, physical, and social conditions [17,18]. Socioeconomic, environmental, and sociocultural aspects can influence quality of life [19,20]. A previous study demonstrated quality of life and psychological well-being are impaired in teachers from Brazil [21]. This mentioned study included 517 teachers from public and private schools in Brazil and evidenced that approximately 20% showed poor indices of general quality of life, ~17% poor quality of life in the physical domain, ~18% in the psychological domain, and ~17% in social domain [21]. In addition, the regression analysis indicated that the meaning of life explained 42% of the variability in the general quality of life and 51% and 27% from the psychological and physical domains, respectively [21]. Although physical activity practice can increase the quality of life in different populations [22,23], the lack of time for physical activity due to the work routine may be related to worse mental health and increased stress in this class of professionals [5].

Physical activity is one lifestyle habit that can improve quality of life and stress levels. Physical activity is defined as any body movement produced by the musculoskeletal system where energy expenditure is above resting levels [24]. Lower frequency of physical activity practice increases the risk of having stress levels, which was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., due to social distancing and increased workload due to teleworking) [25,26]. Dias et al. (2017) [27] evidenced that ~72% of Brazilian public school teachers reported insufficient physical activity. Also, approximately 26% of the physical education teachers from Brazil reported did not practice physical activity during COVID-19, and 10.3% increased their consumption of alcoholic drinks [27], which may be due to the stressful and challenging nature of teaching work during this period [28]. On the other hand, physical activity practice was associated with a better quality of life for workers at a university [29]. In addition, previous studies demonstrated that physical activity practice positively affects job satisfaction and job stress [30,31]. A previous study by Bogaert et al., (2014) [32] observed that physical activity practice in leisure time was associated with perceived health in teachers. Although interesting, few studies evaluated the possible effects of physical exercise on quality of life, especially considering the stress level in public school teachers. Teachers with chronic musculoskeletal pain involved in six weeks of yoga improved their pain and mental health scores [33].

Among the gaps that the present study is advancing, considering the specificity of each domain of quality of life in relation to self-perception of stress is one of them, as such procedures will help to understand which domains are related and which are more strongly related than the others. It is also noteworthy that the instrument used in this study to assess quality of life is composed of eight different domains, providing larger domains when compared to the WHOQol [34], for example. Furthermore, this appears to be the first study to evaluate the role of physical activity in the relationship between stress and quality of life in public school teachers.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to investigate the relationship between stress levels and quality of life in public school teachers in a Brazilian city and verify the role of physical activity in this relationship. We expected to observe associations between lower quality of life and high self-perception of stress in teachers. Also, we expected that physical activity levels could mitigate the relationship between lower quality of life domains and high levels of stress.

2. Materials and Methods

All procedures of this cross-sectional observational (type of study in which observations are made over a certain period of time, in which relationships between a dependent variable and independent variables are analyzed) study were approved by the research ethics committee at São Paulo State University (CAAE: 72191717.9.0000.5402). The participants were informed about the procedures and objectives of the research, and those who agreed to participate signed the statement of consent before their participation.

2.1. Participants

The sample of the present study was composed of 231 teachers from five geographic regions of the city of Presidente Prudente, located in the State of São Paulo (southeast region of Brazil).

We provided a posteriori post hoc power calculation using the formula proposed by Rosner (2011) [35] for power calculation comparing two groups, considering the average quality of life score from all the eight specific domain scores according to stress level (low-level vs. high-level groups). The results are presented below:

where (µ1, σ) and (µ2, σ) are the means and variances of the two respective groups and η1, η2 are the sample sizes of the two groups, considering an alfa error of 0.05. When we used z-scored values for the calculation (since our variable was skewed), the power analysis resulted in 82.8%, as presented below:

| −(1.96) + 0.335/√ (0.7702/76) + (0.9342/159) = 0.946 critical Z value = 0.828 (converted value) = 82.8% power. |

The criteria for inclusion in this research were (i) being a working teacher in the state education network in the city of Presidente Prudente and (ii) agreeing to respond to the questionnaire and have their anthropometric measurements evaluated by signing the Free and Informed Consent Form. The following exclusion criteria were considered: (i) not completely answering any of the study questionnaires and (ii) missing or refusing to take anthropometric measurements.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection was carried out in the school environment at a time agreed with the principals and teachers at public schools so as not to disrupt the work routine. All assessments carried out via questionnaire were face-to-face.

2.2.1. Stress Level

The stress was assessed by the perception of the current level of stress. A Likert scale (i.e., very low, low, moderate, intense, and very intense) was used for the participant’s answers. In general, Likert scales can be used in the literature to assess participants’ feelings and perceptions regarding certain topics [36,37]. Thus, this instrument is commonly used to assess stress levels worldwide [38,39]. Based on the responses, those participants who reported very low or low stress were categorized as low stress, while those who reported moderate, intense, or very intense were classified as having a high level of stress.

2.2.2. Quality of Life

Quality of life was assessed using the instrument proposed by Ware et al., denominated Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), which evaluates eight different domains [40] and had its reproducibility and validity tested in the Brazilian population [41]. The quality of life domains assessed by this instrument are functional capacity, physical limitations, body pain, general health status, vitality, social aspects, emotional aspects, and mental health.

2.2.3. Habitual Physical Activity

Habitual physical activity was assessed by the questionnaire of Baecke et al. [42], which was validated against gold standard methods for measuring physical activity, such as accelerometry, in the Brazilian population [43]. This instrument assesses the different domains of physical activity, considering occupational activities (load you have to lift at work; time you need to walk at work; how much you sweat and feel fatigued), leisure-time sports activities (amount of time, weekly frequency, and intensity of sports practice) and commuting activities (time spent actively commuting to work, shopping, etc…). The sum of the scores of all domains provides a dimensionless score, where the highest value indicates that the participant is more physically active. Because it is an instrument that broadly assesses physical activity in different domains and can also be translated for the Brazilian population, this questionnaire was chosen for the present study.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data normality was analyzed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. When normality was detected, Student’s t-test was performed for independent samples (Low stress vs. High stress), and data were presented as mean and standard deviation. When normality was not detected, the Mann–Whitney test was used, and the variables were presented as median and interquartile range. The association between stress level and quality of life domains was analyzed in two multivariate models: model 1 (adjusted for sex, age, and socioeconomic status) and model 2 (model 1 + physical activity level). To perform this association, a Generalized Linear Model with log-transformed values of domain-specific quality of life scores with robust variance adjustment was used, presenting beta coefficients and 95% confidence intervals considering the stress level as a factor (low level vs. high level). A quantile regression model was used to analyze the association between median (50th percentile) scores of quality of life and stress level, considering the very low stress level as the reference category. The statistical package used was IBM SPSS 25.0, and the statistical significance adopted was 5%.

3. Results

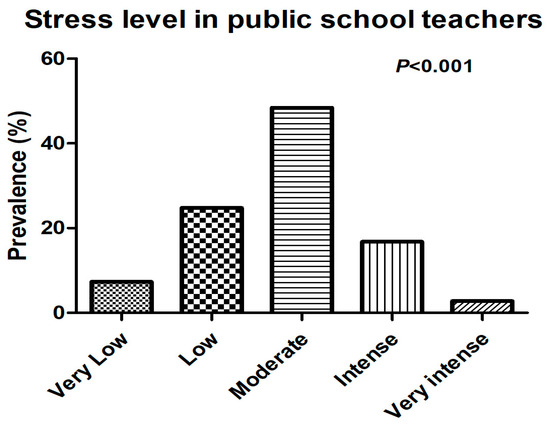

The self-reported prevalence of stress by public school teachers can be considered high, as approximately 50% of teachers reported having moderate stress, while 16.8% reported having intense stress. Only 2.8% report experiencing very intense stress. This information is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Self-reported prevalence of stress by public school teachers.

In Table 1, the variables characterizing the agreement sample are compared with self-reported stress levels (low stress versus high stress). The highest quality of life scores were obtained in the physical limitation and emotional limitation domains in teachers with low stress. There was a significant difference in the domains of physical limitation, general health status, vitality, social aspects, mental health, pain, functional capacity, emotional limitations, all these values being higher in teachers with a low level of stress.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

Table 2 presents the multivariate models considering the association between stress level and quality of life in teachers. The domain of physical limitation (p < 0.001), general health status (p = 0.002), vitality (p < 0.001), social aspects (p < 0.001), mental health (p < 0.001), functional capacity (p = 0.006), and emotional limitations (p < 0.001) were associated with high levels of stress in model 1 (adjusted for sex, age, and socioeconomic status). Thus, considering model 1, only the domain of pain (p = 0.076) was not associated with high levels of stress (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between stress and quality of life in public school teachers (n = 231).

The quantile regression model between quality of life and stress level is presented in Table 3. Participants with high stress levels showed lower (poor) median scores of physical limitation and general health status when compared to those with very low stress levels. The median domain scores of vitality, social aspects, and mental health showed a significant decrease (worsening) from moderate to high/very high stress levels when compared to participants with very low stress levels.

Table 3.

Quantile regression model for the association between stress level and quality of life domain scores in public school teachers (n = 231).

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to analyze whether the level of perceived stress was related to a worse score of quality of life in teachers considering the level of habitual physical activity. As expected, our first hypothesis was confirmed, as high stress level was associated with a worse score of quality of life in different domains (Table 2). Also, our second hypothesis was partially confirmed. Physical activity practice was able to attenuate the association between worse scores of quality of life and high levels of stress. However, this attenuation was observed in only one (functional capacity) out of seven domains of quality of life. In addition, the prevalence of perceived stress in public school teachers in a Brazilian city can be considered high.

Teachers with a high level of perceived stress have lower scores in seven of the eight domains of quality of life when compared to teachers with a low level of stress. Furthermore, the high level of stress was inversely related to better quality of life. Our study evidenced that stress level was associated with mental health and emotional role domains. A possible influence, at least in part, is the fact that high levels of stress are related to burnout syndrome, as demonstrated by Australian teachers [44]. Burnout syndrome and stress can lead to mental health issues (e.g., anxiety and depression) [45], which could directly impact the quality of life domains such as mental health and emotional role. Also, our results indicate an inverse relationship between stress and quality of life domains such as general state of health and vitality, which may be influenced by fatigue [46]. The fatigue arising from stress seems to be a key factor in reducing the perception of health and vitality [46]. High levels of stress were also inversely related to functional capacity. One of the mechanisms that may act in this relationship is that stress would contribute to increases in cortisol levels [47]. Elevated cortisol levels for a long period could impair muscle function, which could contribute to a decrease in functional capacity [48].

Despite this association between stress level and quality of life, physical activity has been considered an important tool in reducing stress and increasing the quality of life of teachers [49,50]. In the present study, the associations between high levels of stress and functional capacity were attenuated after the inclusion of physical activity in the adjusted model. Physical activity practice reduces the cortisol level and contributes to the increase in hormones related to well-being feeling, such as endorphins [51]. Thus, these effects of exercise on hormonal function could explain, at least in part, the attenuation of the association between stress and quality of life. Demmin et al. [49], in a study with American teachers, observed that meditation linked to aerobic exercise contributed to mental health and well-being in teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic, which would certainly contribute to a better perception of quality of life.

Regarding the attenuation of the association between stress and functional capacity, it is well-established that physical activity contributes to an increase in muscle strength and muscle activity [52]. The constant practice of physical activity, mainly via strength and multimodal exercises, has been associated with improvements in functional capacities such as strength, coordination, agility, and balance [53,54]. Thus, these effects of exercise on functional capacity domains could explain, at least in part, the attenuation of the association between stress and quality of life demonstrated in our study.

It should be highlighted in our study that we observed that approximately 70% of school teachers reported being stressed. Similar results were evidenced in previous studies [55,56] with different nationalities. Parthasarathy et al. observed that 85% of American school teachers reported being sometimes/often stressed [55]. Biernat et al. [56] also demonstrated high values in the prevalence of self-reported stress in teachers from Poland. The high workload, insufficient remuneration, and poor infrastructure conditions are some of the reasons reported by teachers that may contribute to this condition of high perceived stress level.

Although presenting interesting and relevant findings, our study also presents limitations that should be considered. The present study has a cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to consider causal relationships. Also, we determined the habitual physical activity practice via a questionnaire, which makes it difficult to determine the intensities of physical activity as assessed by accelerometry. The self-report physical activity practice by questionnaire is susceptible to the bias of memory and should be considered in the interpretation of the results. However, it should be highlighted that the Baecke questionnaire is validated for the Brazilian population when compared to gold standard methods for measuring physical activity (i.e., accelerometry). In addition, the attenuation of the relationship between higher levels of stress and quality of life domains in public school teachers in a Brazilian city should be considered with caution. To confirm this attenuation and to what extent physical activity acts as a mediator or moderator in the relationship, at least in parts, a mediation analysis would be more appropriate. However, our data did not meet the basic assumptions, and therefore, we performed the statistical analysis using Poisson Regression, with the covariates being inserted in a hierarchical model. Another limitation to be reported is the absence of a focus group in the present study or the conduct of interviews with teachers, which could help to better understand the possible causes of stress and also the self-perception of these professionals regarding this situation.

One of the novelties of the present study was to consider the analysis of the specificity of each quality of life domain separately. Another point is that this appears to be the first study to investigate the role of physical activity in the relationship between perceived stress and quality of life in teachers, with attenuation being observed in only one of the domains (functional capacity) in this important professional class.

As strong points, we emphasize the fact that this study was carried out in a developing country like Brazil, presenting the characteristics of countries in this economic condition since most of the data have been from developed countries. As practical applications, we emphasize the importance of encouraging physical activity in teachers in order to mitigate, at least in some domains, the relationship between high levels of stress and lower quality of life.

As suggestions for future studies, longitudinally analyzing the cause-and-effect associations between stress and QoL and the role of physical activity is something that needs to be advanced. Considering strategies for reducing stress in teachers, investigating the effectiveness of intervention programs via physical activity in the school environment with teachers could be a good alternative to reduce the stress load on these professionals.

5. Conclusions

Approximately 70% of teachers participating in this study reported having high levels of stress. Higher levels of stress were associated with seven out of eight domains of the quality of life. However, the physical activity practice attenuated the relationship between higher levels of stress and functional capacity domains of quality of life in secondary public school teachers in a Brazilian city. Therefore, encouraging teachers to practice physical activity can be an alternative for reducing stress levels and improving quality of life. Programs that could contribute to increasing physical activity in the workplace, for example, could be an alternative to be tested for these objectives.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design were performed by C.C.M.d.S., L.D.D. and V.S.B. Data collection was performed by C.C.M.d.S. and L.D.D. Data analysis was performed by L.D.D. and V.S.B. Data interpretation was performed by C.C.M.d.S., A.B.d.S., I.C.L., E.G.L., E.P.A., W.T., E.D.d.L.M., L.D.D. and V.S.B. The first draft of the manuscript was written by C.C.M.d.S. and all authors reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES) [Finance Code 001] and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) as a scholarship for WT [grant number #2021/08655-2]).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Research Committee of the Sao Paulo State University (CAAE: 72191717.9.0000.5402—08/11/2017), Presidente Prudente.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained in writing from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the volunteers who agreed to participate in this research, as well as all of the members of the Physical Activity and Health Scientific Research Group (GEAFS)—UNESP/Brazil who assisted with data collection sampling and logistics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stacey, M.; McGrath-Champ, S.; Wilson, R. Teacher Attributions of Workload Increase in Public Sector Schools: Reflections on Change and Policy Development. J. Educ. Chang. 2023, 24, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, M.; McGrath-Champ, S.; Wilson, R.; Fitzgerald, S.; Stacey, M. Teacher Workload in Australia: National Reports of Intensification and Its Threats to Democracy. In New Perspectives on Education for Democracy: Creative Responses to Local and Global Challenges; Taylor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hero, J.L. Level Shifting, Workload, School Location, Teacher Competency and Principal Leadership Skills in Public Elementary Schools. Int. J. Acad. Pedagog. Res. (IJAPR) 2020, 4, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Felsing, C.; Seibt, R.; Stoll, R.; Kreuzfeld, S. Working Time Structure of Secondary School Teachers in the Course of the Day and the Week-an App-Based Pilot Study. Arbeitsmed Sozialmed Umweltmed 2019, 54, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzfeld, S.; Felsing, C.; Seibt, R. Teachers’ Working Time as a Risk Factor for Their Mental Health—Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study at German Upper-Level Secondary Schools. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The Association between Long Working Hours and Health: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Evidence. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrave, D.; Charlwood, A. What Is the Relationship between Long Working Hours, over-Employment, under-Employment and the Subjective Well-Being of Workers? Longitudinal Evidence from the UK. Hum. Relat. 2015, 68, 1491–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.C.; Chen, J.D.; Cheng, T.J. The Associations between Long Working Hours, Physical Inactivity, and Burnout. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Stress. Available online: https://www.who.int//news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI87vf5Y7WggMV0tHCBB3uqwDYEAAYASAAEgLeU_D_BwE (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Hojo, M. Association between Student-Teacher Ratio and Teachers’ Working Hours and Workload Stress: Evidence from a Nationwide Survey in Japan. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, T.; Gillet, N.; Beltou, N.; Tellier, F.; Fouquereau, E. Effects of Workload on Teachers’ Functioning: A Moderated Mediation Model Including Sleeping Problems and Overcommitment. Stress Health 2018, 34, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomuad, P.D.; Antiquina, L.M.M.; Cericos, E.U.; Bacus, J.A.; Vallejo, J.H.; Dionio, B.B.; Bazar, J.S.; Cocolan, J.V.; Clarin, A.S. Teachers’ Workload in Relation to Burnout and Work Performance. Int. J. Educ. Policy Res. Rev. 2021, 8, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Yamamura, S. The Relationship Between Long Working Hours and Stress Responses in Junior High School Teachers: A Nationwide Survey in Japan. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 775522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, B.; Marwaha, K.; Sanvictores, T.; Ayers, D. Physiology, Stress Reaction. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi Barcellos Dalri, R.D.C.; Da Silva, L.A.; Mendes, A.M.O.C.; Do Carmo Cruz Robazzi, M.L. Nurses’ Workload and Its Relation with Physiological Stress Reactions. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2014, 22, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, L.B.; Burke, T.N.; Christofolleti, G.; de Alencar, G.P. Burnout Syndrome, Work Ability, Quality of Life and Physical Activity in Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Campo Grande, Brazil. Work 2023. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whoqol Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Position Paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, N. Dictionary of Quality of Life and Health Outcomes Measurement, 1st ed.; International Society for Quality of Life Research: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2015; ISBN 0996423109. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.Y.; Han, L.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Luo, S.; Hu, J.W.; Sun, K. The Influence of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior on Health-Related Quality of Life among the General Population of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, S.A.; Magee, C.A.; Cliff, D.P. Trajectories and Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life during Childhood. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damásio, B.F.; de Melo, R.L.P.; da Silva, J.P. Sentido de Vida, Bem-Estar Psicológico e Qualidade de Vida Em Professores Escolares. Paid. (Ribeirão Preto) 2013, 23, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, G.; Reis, R.S.; Rech, C.R.; Hallal, P.C. Quality of Life and Physical Activity among Adults: Population-Based Study in Brazilian Adults. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarabottolo, C.C.; Tebar, W.R.; Gobbo, L.A.; Ohara, D.; Ferreira, A.D.; da Silva Canhin, D.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Analysis of Different Domains of Physical Activity with Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults: 2-Year Cohort. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- de Camargo, E.M.; Piola, T.S.; Dos Santos, L.P.; de Borba, E.F.; de Campos, W.; da Silva, S.G. Frequency of Physical Activity and Stress Levels among Brazilian Adults during Social Distancing Due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19): Cross-Sectional Study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2021, 139, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.S.S.E.; Rose Elizabeth Cabral, B.; Leão, L.L.; das Graças Pena, G.; de Pinho, L.; de Magalhães, T.A.; Silveira, M.F.; Rossi-Barbosa, L.A.R.; Silva, R.R.V.; Haikal, D.S.A. Working Conditions, Lifestyle and Mental Health of Brazilian Public-School Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatriki 2021, 32, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, D.F.; Loch, M.R.; González, A.D.; de Andrade, S.M.; Mesas, A.E. Insufficient Free-Time Physical Activity and Occupational Factors in Brazilian Public School Teachers. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguchi, Y.; Iwasaki, S.; Kanchika, M.; Nitta, T.; Mitake, T.; Nogi, Y.; Kadowaki, A.; Niki, A.; Inoue, K. Gender Differences in the Relationships between Perceived Individual-Level Occupational Stress and Hazardous Alcohol Consumption among Japanese Teachers: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, S.S.; Alemdaroǧlu, I.; Karaduman, A.A.; Yilmaz, Ö.T. The Effects of Physical Activity on Sleep Quality, Job Satisfaction, and Quality of Life in Office Workers. Work 2019, 63, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proper, K.I.; Staal, B.J.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; van der Beek, A.J.; van Mechelen, W. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Programs at Worksites with Respect to Work-Related Outcomes. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2002, 28, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conn, V.S.; Hafdahl, A.R.; Cooper, P.S.; Brown, L.M.; Lusk, S.L. Meta-Analysis of Workplace Physical Activity Interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, I.; De Martelaer, K.; Deforche, B.; Clarys, P.; Zinzen, E. Associations between Different Types of Physical Activity and Teachers’ Perceived Mental, Physical, and Work-Related Health. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metri, K.G.; Raghuram, N.; Narayan, M.; Sravan, K.; Sekar, S.; Bhargav, H.; Babu, N.; Mohanty, S.; Revankar, R. Impact of Workplace Yoga on Pain Measures, Mental Health, Sleep Quality, and Quality of Life in Female Teachers with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Randomized Controlled Study. Work 2023, 76, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.; Power, M.; Orley, J.; Herrman, H.; Schofield, H.; Murphy, B.; Metelko, Z.; Szabo, S.; Pibernik-Okanovic, M.; Quemada, N.; et al. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, B.A. Fundamentals of Biostatistics, 7th ed.; Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-538-73349-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, I.-S. Comparative Analysis of the Correlation between Anxiety, Salivary Alpha Amylase, Cortisol Levels, and Athletes’ Performance in Archery Competitions. J. Exerc. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 22, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahipalan, M.; Sheena, S. Workplace Spirituality and Subjective Happiness Among High School Teachers: Gratitude As A Moderator. EXPLORE 2019, 15, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, D.; Escribano, D.; Franco-Martínez, L.; Contreras-Aguilar, M.D.; Bernal, L.J.; Ceron, J.J.; Rojo-Villada, P.A.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; Tvarijonaviciute, A. Evaluation of the Effect of a Live Interview in Journalism Students on Salivary Stress Biomarkers and Conventional Stress Scales. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibewa, T.A.; Adams, T.A.; Gill, A.K.; Mazin, L.E.; Gerras, J.E.; Hasson, R.E. Stress Coping Strategies and Stress Reactivity in Adolescents with Overweight/Obesity. Stress Health 2021, 37, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-Ltem Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguardia, J.; Campos, M.R.; Travassos, C.; Najar, A.L.; dos Anjos, L.A.; Vasconcellos, M.M. Brazilian Normative Data for the Short Form 36 Questionnaire, Version 2. Rev. Bras. De Epidemiol. 2013, 16, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baecke, J.A.H.; Burema, J.; Frijters, J.E.R. A Short Questionnaire for the Measurement of Habitual Physical Activity in Epidemiological Studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 36, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebar, W.R.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Fernandes, R.A.; Damato, T.M.M.; De Barros, M.V.G.; Mota, J.; Andersen, L.B.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Validity and Reliability of the Baecke Questionnaire against Accelerometer-Measured Physical Activity in Community Dwelling Adults According to Educational Level. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, A.; Forrest, K.; Sanders-O’Connor, E.; Flynn, L.; Bower, J.M.; Fynes-Clinton, S.; York, A.; Ziaei, M. Teacher Stress and Burnout in Australia: Examining the Role of Intrapersonal and Environmental Factors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 25, 441–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.V. Work-Related Mental Consequences: Implications of Burnout on Mental Health Status Among Health Care Providers. Acta Inform. Medica 2015, 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintzman, C.S.; Kampf, T.D.; John-Henderson, N.A. Changes in Vitality in Response to Acute Stress: An Investigation of the Role of Anxiety and Physiological Reactivity. Anxiety Stress Coping 2022, 35, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.C.; Chung, M.I.; Lee, Y.D. Modulation of Pain Sensation by Stress-Related Testosterone and Cortisol. Anaesthesia 2012, 67, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, G.M.E.E.; Van Schoor, N.M.; Van Rossum, E.F.C.; Visser, M.; Lips, P. The Relationship between Cortisol, Muscle Mass and Muscle Strength in Older Persons and the Role of Genetic Variations in the Glucocorticoid Receptor. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2008, 69, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmin, D.L.; Silverstein, S.M.; Shors, T.J. Mental and Physical Training with Meditation and Aerobic Exercise Improved Mental Health and Well-Being in Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 847301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B.; Brett-MacLean, P.; Burback, L.; Agyapong, V.I.O.; Wei, Y. Interventions to Reduce Stress and Burnout among Teachers: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidari, A.; Ghavidel-Parsa, B.; Rajabi, S.; Sanaei, O.; Toutounchi, M. The Acute Effect of Maximal Exercise on Plasma Beta-Endorphin Levels in Fibromyalgia Patients. Korean J. Pain 2016, 29, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C.; Stokes, M.; Samuel, D. Muscle Strength, Functional Endurance, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Active Older Female Golfers. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocalini, D.S.; Dos Santos, L.; Serra, A.J. Physical Exercise Improves the Functional Capacity and Quality of Life in Patients with Heart Failure. Clin. (Sao Paulo) 2008, 63, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustosa, L.P.; Silva, J.P.; Coelho, F.M.; Pereira, D.S.; Parentoni, A.N.; Pereira, L.S.M. Impact of Resistance Exercise Program on Functional Capacity and Muscular Strength of Knee Extensor in Pre-Frail Community-Dwelling Older Women: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Rev. Bras. Fisioter. 2011, 15, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, N.; Li, F.; Zhang, F.; Chuang, R.J.; Mathur, M.; Pomeroy, M.; Noyola, J.; Markham, C.M.; Sharma, S.V. A Cross-Sectional Study Analyzing Predictors of Perceived Stress Among Elementary School Teachers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Workplace Health Saf. 2022, 70, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, E.; Piątkowska, M.; Rozpara, M. Is the Prevalence of Low Physical Activity among Teachers Associated with Depression, Anxiety, and Stress? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).