Implementation of Brief Admission by Self-Referral in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Sweden: Insights from Implementers and Staff

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Implementation Processes

2.3. Planning

2.3.1. Initiation

2.3.2. Executive Boards

2.3.3. Collaboration among Units with Brief Admission Experience

2.3.4. Feasibility Study—Could This Also Work for Adolescents in Sweden?

2.4. Education

2.4.1. DBT Training

2.4.2. Brief Admission Team

2.4.3. Brief Admission Training of the Staff at the Emergency Unit

2.4.4. Staff at the Outpatient Units

2.5. Finance

2.6. Restructuring

Changes in the Physical Structure of the Ward and the Record System

2.7. Quality Management

2.8. Policy Development and Reform

2.9. Characteristics of the Brief Admission Concept for Adolescents

2.9.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.9.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.9.3. Patient Recruitment

2.9.4. Introduction to the Concept

2.9.5. Negotiating and Signing the Contract

2.9.6. Coming to the Unit for a Brief Admission

2.9.7. During the Brief Admission

2.9.8. Discharge Procedure

2.9.9. Termination of Contract

3. Results

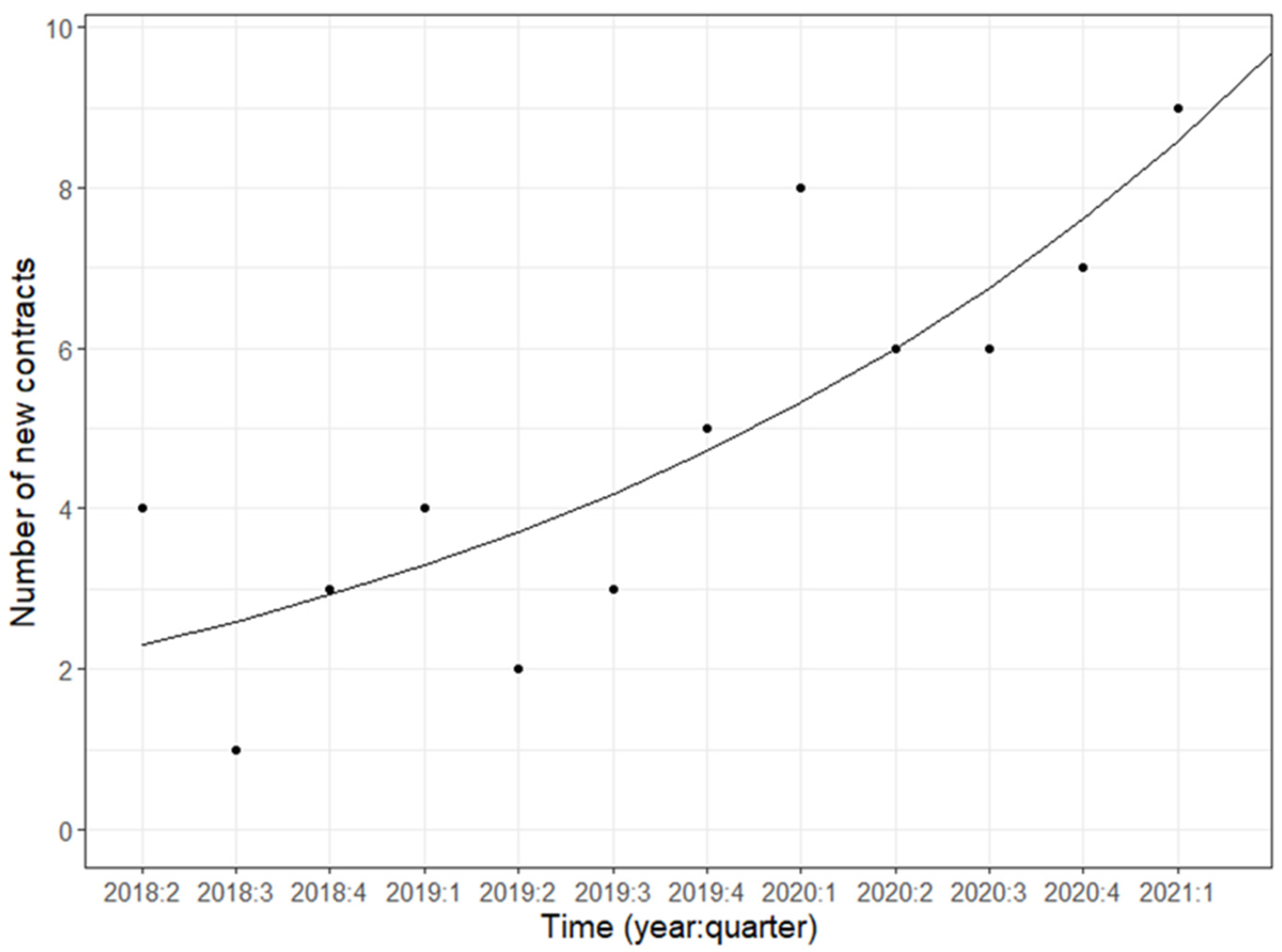

3.1. Early Clinical Experience and Outcome of Brief Admissions for Adolescents

3.1.1. Characteristics of Patients with Brief Admissions

3.1.2. Staff Experience Measures

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Achievement Factors

4.3. Hypothetical Earnings, Strengths, and Limitations

4.4. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- My goals

- Which are my early signs before calling for a brief admission?

- How do I get admitted?

- How does a brief admission stay proceed?

- How can the staff support me to improve my health and achieve my goals?

- Is there anything else that is especially important for me during the stay?

- Is there anything special I need to arrange during my stay?

- My promises during the brief admission stay are as follows:

- I have read and understood the content of the contract and will follow it.

- Signatures

References

- Kaplan, T.; Racussen, L. A crisis recovery model for adolescents with severe mental health problems. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen-Bauer, K.; Heyerdahl, S.; Hatling, T.; Jensen, G.; Olstad, P.M.; Stangeland, T.; Tinderholt, T. Admissions to acute adolescent psychiatric units: A prospective study of clinical severity and outcome. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2011, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.L.; Semovski, V.; Lapshina, N. Adolescent inpatient mental health admissions: An exploration of interpersonal polyvictimization, family dysfunction, self-harm and suicidal behaviours. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taiminen, T.J.; Kallio-Soukainen, K.; Nokso-Koivisto, H.; Kaljonen, A.; Helenius, H. Contagion of deliberate self-harm among adolescent inpatients. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 37, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, T.N.; Shaver, J.A.; Linehan, M.M. On the potential for iatrogenic effects of psychiatric crisis services: The example of dialectical behavior therapy for adult women with borderline personality disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, B.A.; Holmström, E.; Eberhard, S.; Lindgren, A.; Rask, O. Introducing brief admissions by self-referral in child and adolescent psychiatry: An observational cohort study in Sweden. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, J. Why psychiatrists are reluctant to diagnose: Borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, J.G.; Herpertz, S.C.; Skodol, A.E.; Torgersen, S.; Zanarini, M.C. Borderline personality disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodol, A.E.; Gunderson, J.G.; McGlashan, T.H.; Dyck, I.R.; Stout, R.L.; Bender, D.S.; Grilo, C.M.; Shea, M.T.; Zanarini, M.C.; Morey, L.C.; et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Evans, N.; Gillen, E.; Longo, M.; Pryjmachuk, S.; Trainor, G.; Hannigan, B. What do we know about the risks for young people moving into, through and out of inpatient mental health care? Findings from an evidence synthesis. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2015, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videler, A.C.; Hutsebaut, J.; Schulkens, J.E.M.; Sobczak, S.; van Alphen, S.P.J. A life span perspective on borderline personality disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flyckt, L.K. Brief admission-a promising novel crisis management method. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Borderline Personality Disorder: Recognition and Management Clinical Guideline [CG78]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Dutch Psychiatric Multidisciplinary Guideline Committee. Dutch Multidisciplinary Guidelines for Personality Disorders; Trimbos-Institute: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eckerström, J.; Carlborg, A.; Flyckt, L.; Jayaram-Lindström, N. Patient-initiated brief admission for individuals with emotional instability and self-harm: An evaluation of psychiatric symptoms and health-related quality of life. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 43, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckerström, J.; Flyckt, L.; Carlborg, A.; Jayaram-Lindström, N.; Perseius, K.I. Brief admission for patients with emotional instability and self-harm: A qualitative analysis of patients’ experiences during crisis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckerström, J.; Allenius, E.; Helleman, M.; Flyckt, L.; Perseius, K.I.; Omerov, P. Brief admission (BA) for patients with emotional instability and self-harm: Nurses’ perspectives—Person-centred care in clinical practice. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2019, 14, 1667133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljedahl, S.; Helleman, M.; Daukantaite, D.; Westling, S.; Brief Admission: Manual for Training and Implementation Developed from the Brief Admission Skåne Randomized Controlled Trial (BASRCT). Training Manual. Available online: https://lucris.lub.lu.se/ws/portalfiles/portal/33715270/BA_manual_ENG_web.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Westling, S.; Daukantaite, D.; Liljedahl, S.I.; Oh, Y.; Westrin, Å.; Flyckt, L.; Helleman, M. Effect of brief admission to Hospital by self-referral for individuals who self-harm and are at risk of suicide: A randomized clinical trial. AMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e195463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C.; Proctor, E.K.; Carpenter, C.R.; Griffey, R.T.; Bunger, A.C.; Glass, J.E.; York, J.L. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2012, 69, 123–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, E.; Berk, M.S.; Asarnow, J.R.; Adrian, M.; Cohen, J.; Korslund, K.; Avina, C.; Hughes, J.; Harned, M.; Gallop, R.; et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 777–785, appears in JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamarina-Perez, P.; Mendez, I.; Singh, M.K.; Berk, M.; Picado, M.; Font, E.; Moreno, E.; Martínez, E.; Morer, A.; Borràs, R.; et al. Adapted dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with a high risk of suicide in a community clinic: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2020, 50, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindkvist, R.M.; Westling, S.; Eberhard, S.; Johansson, B.A.; Rask, O.; Landgren, K. ‘A safe place where I am welcome to unwind when I choose to’—Experiences of brief admission by self-referral for adolescents who self-harm at risk for suicide: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englander, M. Empathy in a Social Psychiatry. In Phenomenology and the Social Context of Psychiatry. Social Relations, Psychopathology, and Husserl’s Philosophy; Englander, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2018; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nyttingnes, O.; Ruud, T. When patients decide the admission—A four year pre-post study of changes in admissions and inpatient days following patient controlled admission contracts. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, M.; Bulik, C.M.; Gustafsson, S.A.; Welch, E. Self-admission in the treatment of eating disorders: An analysis of healthcare resource reallocation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skott, M.; Durbeej, N.; Smitmanis-Lyle, M.; Hellner, C.; Allenius, E.; Salomonsson, S.; Lundgren, T.; Jayaram-Lindström, N.; Rozental, A. Patient-controlled admissions to inpatient care: A twelve-month naturalistic study of patients with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses and the effects on admissions to and days in inpatient care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigrunarson, V.; Moljord, I.E.O.; Steinsbekk, A.; Eriksen, L.; Morken, G. A randomized controlled trial comparing self- referral to inpatient treatment and treatment as usual in patients with severe mental disorders. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2017, 71, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, C.T.; Benros, M.E.; Maltesen, T.; Hastrup, L.H.; Andersen, P.K.; Giacco, D.; Nordentoft, M. Patient-controlled hospital admission for patients with severe mental disorders: A nationwide prospective multicentre study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 137, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trochim, W.M.K. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 3rd ed.; Atomic Dog Publishing: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berk, M.S.; Starace, N.K.; Black, V.P.; Avina, C. Implementation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Suicidal and Self-Harming Adolescents in a Community Clinic. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Implementation Strategy | Application |

|---|---|

| Planning | |

| Build a coalition | The goal was to organizing an implementation team with providers, managers, and stakeholders at different levels for children and adolescents in the region. |

| Conduct local consensus discussions | The idea to implement the model came from a significant clinical problem, and the implementation team discussed whether brief admissions could be appropriate for the problem. |

| Involve executive boards | The executive board of the clinic as well as the senior psychiatrists were involved throughout the implementation process, actively participating in planning, structure, and evaluation. |

| Visit other sites | The team organized a study visit to the Netherlands where a model for brief admission was in use in an adult and adolescent psychiatric setting. |

| Assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators | The implementation team suggested forming a brief admission team with the goal to adapt and implement brief admission for children and adolescents in the region. |

| Develop academic partnerships | The implementation process was completed in collaboration with researchers from the Department of Child and Adolescent psychiatry and the Department of Adult Psychiatry at Lund University. |

| Stage implementations scale up | Using a preliminary protocol, six patients were included in a pilot study and gained access to brief admission. |

| Education | |

| Create a learning collaborative | A brief admission team was formed that included a senior psychiatrist and two nurses’ aides. |

| Use train-the-trainer strategies | The brief admission team members attended the training for trainers in the adult brief admission model. |

| Develop educational materials | The brief admission team, guided by the adult team, adapted the education manual to be suitable for adolescents. |

| Work with educational institutions | The brief admission team members took part in a DBT training course held by an international authority and his Swedish DBT-colleagues. |

| Conduct ongoing training | The team completed initial comprehensive training of all staff working in the ward, then repeated trainings to introduce new staff members and give updates to senior staff. |

| Conduct educational meetings | Brief lectures were held for providers in adjacent units, administrators, and other organizational stakeholders. |

| Provide ongoing consultation | The adult brief admission team held continuous consultations to facilitate the implementation process. |

| Finance | |

| Access new funding | External funding was sought for a study trip to the Netherlands. |

| Restructure | |

| Change physical standards and equipment | Two rooms that were dedicated for patients participating in brief admissions were prepared. |

| Change record systems | Clinical documentation for all patients was made by a dedicated senior physician. |

| Quality management | |

| Audit and provide feedback | Forms that were adapted for adolescents were prepared to investigate satisfaction with the model. |

| Capture and share local knowledge | The unit had experiences from previous implementation processes with other models. |

| Organize clinician implementation team meetings | The brief admission team had recurrent meetings with the implementation team to reflect on the implementation effort, share lessons learned, and support each other’s learning |

| Provide clinical supervision | A clinician supervised the implementation. The brief admission team members were trained to ensure that they had the skills needed to supervise staff |

| Policy development and reform | |

| Create or change credentialing and standards | The team created an operation that encouraged using the method. The work to make this change continues through training requirements that encourage continued and increased use of the method. |

| Brief Admission by Self-Referral | Emergency Admission | |

|---|---|---|

| Before admission | ||

| Information | Information about brief admission | Information about our 24/7 emergency service |

| Contract negotiation | Individual parts are reviewed: e.g., overreaching six-month goals, early signs of deterioration, preferred approach from staff, and stress-reducing activities | - |

| Contract | The contract is written, and signed by the patient, a parent, the open care therapist, and a brief admission team member | - |

| Approach from staff | Affirmative and welcoming, emphasizing validation | Validation, respect |

| Admission | Patient decision according to contract | Admission after physician’s decision |

| During admission | ||

| Security check | The patient shows what is in their bags and pockets. Cigarettes and lighters are taken and secured | The patient shows what is in their bags and pockets. Cigarettes and lighters are taken and secured |

| Contract reading and treatment plan | The individual contract is read together with a nurse and a treatment plan is written | A treatment plan is written together with patient and parents |

| Treatment length | 1–3 days, maximum three times/month | An average of seven days |

| Accompany parents | If written in the contract | A parent is admitted with the patient |

| Meds—administration | By unit nurse | By unit nurse |

| Meds—adjustments | Adjustments by the open-care physician | Possible, if unit physician considers it justified |

| Daily staff support | 20 min two times per day | Irregularly depending on need |

| Meals | Can eat in privacy | Shared meals |

| Evaluation by psychologist | - | Evaluation usually every other day |

| Evaluation by physician | - | Evaluation usually every other day, also together with a parent |

| Temporary leaves | Yes, according to contract. If the patient can visit their therapist, school, or leisure activity despite the impending crisis, this is encouraged | Possible after agreement with the unit’s physician |

| Overnight leaves | No | Possible after agreement with parents and the unit’s physician |

| Premature discharge | If the patient breaks the contract by self-harming, threatening others, or acting violently | If the patient objects or sabotage offered treatment and not can be converted without coercive care. Symptom escalation often results in an extended treatment period. |

| Discharge procedure | Discharge interview with a brief admission team member. Parents are informed. A brief questionnaire regarding the admission is completed | Discharge interview with the unit physician, staff, and parent. |

| Coercive care | - | Can be applied if the patient suffers from a serious mental disorder, e.g., mania, cannot be cared for in any other way than within 24-h psychiatric care, and opposes such intervention. |

| Counseling for accompanying parents | - | Sometimes the parents ask for counseling, while staff take the initiative at other times. Social services are sometimes contacted about staff concerns |

| Cooperation | Outpatient care unit | Outpatient care unit, sometimes school, social authorities |

| Supervision | - | Different degrees of supervision depending on the illness, the patient’s maturity, and their ability to take personal responsibility |

| Hospital school | - | Sometimes, during prolonged admissions |

| Unit activities | Voluntary | Encouraged to participate |

| Brief Admission for Adolescents | Brief Admission for Adults | |

|---|---|---|

| Negotiation | Parents participate | Next of kin do not participate |

| Security check on admission | Bags checked | Bags are not checked |

| Parents/next-to-kin | Possibility to admit a parent | Next of kin are not admitted |

| Medication | Provided and handled by the ward nurse | Brought and handled by the patient |

| Possibility of supervision | Unit nurse can support staff in not leaving the patient alone when there is an urge to self-harm | No constant supervision |

| Discharge | Parents involved | No approval needed when the adult wants to be discharged |

| Contract re-evaluation | Biannually | Annually |

| Demographics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Girls | 60 | 95% |

| Boys | 3 | 5% |

| Median length (months) of the pre-brief admission period | 9.6 (4.3–23.7) | |

| Mean age (years) when signing the brief admission contract | 14.8 ± 1.7 | |

| F10, Alcohol abuse | 1 | 2% |

| F31, Bipolar disorder | 1 | 2% |

| F32, Major depressive disorder | 24 | 38% |

| F41, Other anxiety disorders | 12 | 19% |

| F42, Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 2 | 3% |

| F43, Reaction on severe stress | 9 | 14% |

| F50, Eating disorders | 4 | 6% |

| F84, Pervasive development disorders | 3 | 5% |

| F90, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | 5 | 8% |

| F93, Emotional disorders (Childhood onset) | 2 | 3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johansson, B.A.; Holmström, E.; Westling, S.; Eberhard, S.; Rask, O. Implementation of Brief Admission by Self-Referral in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Sweden: Insights from Implementers and Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010035

Johansson BA, Holmström E, Westling S, Eberhard S, Rask O. Implementation of Brief Admission by Self-Referral in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Sweden: Insights from Implementers and Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohansson, Björn Axel, Eva Holmström, Sofie Westling, Sophia Eberhard, and Olof Rask. 2024. "Implementation of Brief Admission by Self-Referral in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Sweden: Insights from Implementers and Staff" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010035

APA StyleJohansson, B. A., Holmström, E., Westling, S., Eberhard, S., & Rask, O. (2024). Implementation of Brief Admission by Self-Referral in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Sweden: Insights from Implementers and Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010035