Disclosure of Mental Health Problems or Suicidality at Work: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

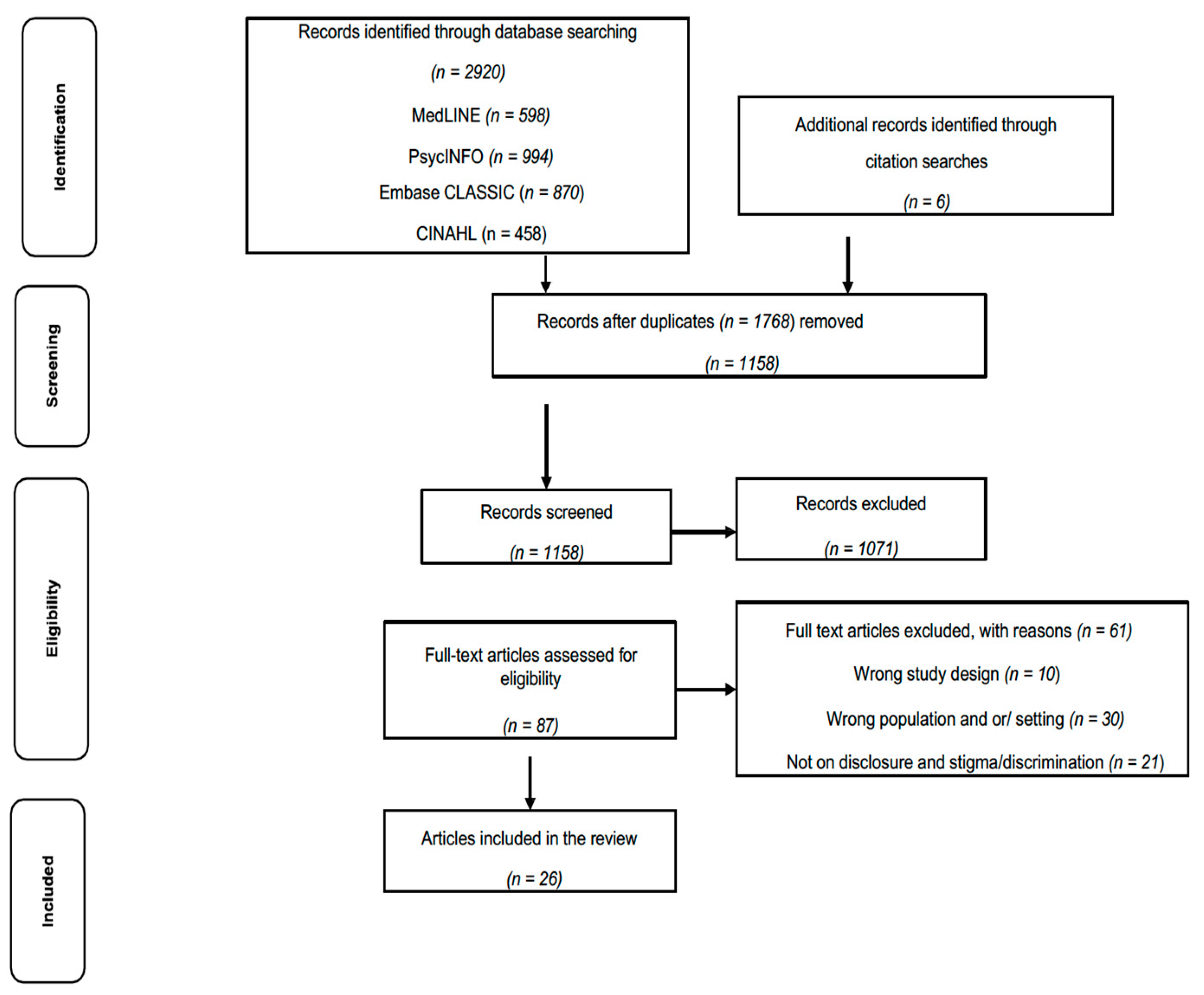

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

| Author (Year), Location | Eligibility Criteria | Sample Characteristics | Study Design | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Studies | ||||

| Bogaers et al. (2021), Denmark [29] | Soldiers with mental health or substance use conditions; soldiers without mental health or substance use conditions; mental health professionals | Participants: n = 46 n = 20 soldiers with mental health or substance use conditions; n = 10 soldiers without mental health or substance use conditions; n = 16 mental health professionals Gender: male (n = 37) Age: 22–57 | Focus groups Content analysis | Five barriers and three enablers Barriers: fear of career consequences, fear of social rejection, lack of leadership support, lack of communication skills surrounding mental health or substance use conditions, masculine workplace cultures Enablers: anticipated positive results, leadership support, work-related mental health or substance made it easier to disclose |

| Brouwers et al. (2020), Netherlands [30] | People with mental illness, work reintegration professionals, employers, HR managers | Participants: n = 27 Gender: female 48.1%, male 37.4 % Age: not reported | Focus groups Thematic content analysis | Five themes: Being exposed to people with mental health problems helped changes attitudes Perceived stigma about mental illness from co-workers Hypothetical issues affecting disclosure decisions included having trust and support from managers Possibility of losing employment and changing attitudes of colleagues after disclosure Most workplaces/managers supportive after disclosure One unique theme (for non-mental health professionals)—mental illness is not talked about |

| Elliot et al. (2020), USA [31] | Mental health professionals living with mental illness | Participants: n = 12 psychotherapists Age: 36–63 Gender: female 75%, male 25% | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | Indirect prejudice more common than indirect discrimination for 75% of participants 66% selectively shared information about their mental illness 92% believed having a mental illness an asset at work 55% described benefits to having a mental illness but said it could be a liability, interfering with job performance |

| Elraz (2018), UK [32] | Individuals with mental health concerns, health professionals, HR professionals, line managers, employees | Participants: n = 16 workers with mental health conditions Age: not reported Gender: not reported | Semi-structured interviews Discourse analysis | Negative societal representations of mental health problems translate into workplaces By gaining special skills as a consequence of their MHC, they are better positioned in their employment, compared to other colleagues Those who disclose, see themselves as champions/pioneers |

| Joyce et al. (2009), Australia [33] | Mental health or generalist nurses with mental health concerns (diagnosed by a medical practitioner), currently receiving treatment for mental ill health and not in a state of acute active psychosis | Participants: n = 29 mental health nurses Age: 24–56 Gender: female 82.7%, male 17.2% | In-depth interviews Discourse analysis | Four subthemes: Declaring mental illness and decision to disclose to co-workers and nurse managers and implications of disclosure for identity as a confident and capable nurse, not somebody who needed therapeutic interventions Collegial support—some management and colleagues will be deliberately destructive to the wellbeing of nurses Some managers are caring, sensitive and supportive Enhancing support—nurses, as well as the nursing profession, has a responsibility to develop an awareness of their attitudes towards mental health |

| King et al. (2021), Australia [34] | Mental health professionals identifying with lived experience (publicly or privately), mental health professionals not identifying with lived experience, staff in designated lived experience roles (peer workers), staff in supervisory roles to the above groups | Participants: n = 33 mental health workers Age: not reported Gender: females 78.7%, males 15.1%, non-binary 6.0% | Semi-structured interview Thematic analysis | Three findings Peer workers reveal the impact of organizational differences in supporting sharing Importance of identity and identity management at work Influence of team culture affects how sharing occurs |

| Lyhne et al. (2021), Netherlands [35] |

| Participants: n = 8 Age: 35–66 Gender: female 62.5%, males 37.5% | Semi-structured interviews Content analysis | Four categories (opportunities/challenges) Struggling with acknowledging depression and disclosure Fear of stigma—disclosure avoided fearing stigma from co-workers/employer Work is a life motivator—work contributes with meaning and substance in life, provides opportunities for managing work participation Striving to complete work tasks at the expense of private life; a strong work identity and commitment to work impose high self-expectations as a worker |

| Peterson et al. (2011), New Zealand [36] | Employed and self-identified as experiencing mental ill health | Participants: n = 22 Age Range: not reported Gender: not reported | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | Pressure to not disclose was due to fear of discrimination Pressures to disclose were legal, practical and moral Legal pressures related to health-related questions on job application forms Practical pressures included ensuring employers could allow time off for appointments or other accommodations Moral pressures included disclosure was the “right thing to do” |

| Peterson et al. (2017), New Zealand [37] |

| Participants: n = 30: n = 15 employees n = 15 employers Age: employees (n = 5, 23–34), (n = 8, 45–54), (n = 1, 55–65) Gender: female 60%, male 36.6% | Semi-structured interviews Thematic content analysis | Critical factors include work has meaning Disclosure mostly occurs at start of employment There are benefits of working Special arrangements, accommodations and flexibility are important The working environment is one of the main reasons employees enjoyed work |

| Rangarajan et al. (2020), India [38] | Clinically stable people with serious mental ill health with a score of ≤2 on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Severity scale, currently employed or employed in the past for at least six months and able to provide valid interviews; Mental health professionals having >15 years of formal education); Employers who had employed people with mental health concerns | Participants: n = 15 employees (n = 5); mental health professionals (n = 5); employers (n = 5) Age: M (SD) 38.26 (8.94) years Gender: females 20%, males 80% | In-depth interviews Content analysis | Reasonable accommodations and supports improves work efficiency, modifications in the workplace environment, modifications in the appraisal, integration of mental health and employment services, and supportive employer policies Undue burden a major concern for employers and mental health professionals, compared to those with lived experience Stigma reduction and disclosure of mental health problems are important prerequisites for reasonable accommodations |

| Rusch et al. (2017), Germany [39] |

| Participants: n = 56 Age: M (SD) 34.8 (9.4) Gender: male 91% | Focus group Content analysis | Soldiers with serious mental health ill health struggle with disclosure decisions Disclosure remains deeply personal and difficult; decisions are shaped by circumstances, some beyond the individual’s control, such as the stigma associated with mental ill health in society and in the military Stigma remains a barrier to reintegration and recovery |

| Siegel et al. (2020), USA [40] | Working men who reported a clinical diagnosis of an eating issue | Participants: n = 14 Age: (M = 27.86; SD = 6.95) Gender: male 100% | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | Fear of stigma and (non) disclosure, emotional reactions, coping strategies, and impaired work performance Vigilance required to remain undetected combined with the pressure to present with masculinity at work made work life challenging White men may be negatively impacted by their social locations |

| Stratton et al. (2018), Australia [41] |

| Participants: n = 13 Age: not reported Gender: female 38.4%, male 61.5% | Focus groups Thematic analysis | Male-dominated workplace affected disclosure decisions, even for those who had already done so, as influenced by barriers to disclosure Six negative themes of internal and external factors influencing the decision-making process: knowledge about symptoms, self-discrimination (internal), stigma and discrimination by others, limited managerial support, dissatisfaction with services, and/or a risk of job or financial loss (external) |

| Toth et al. (2014), Canada [42] | Post-secondary education employees diagnosed with a mental disorder recognized under the DSM-IV-TR (3) by a qualified health professional | Participants: n = 13 Age: 21 to 55 Gender: female 76.9%, male 23.0% | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | Default position of nondisclosure adopted due to fear of stigma Employees need a reason to disclose Decision-making process involves a risk–benefit analysis Training managers and staff would help reduce stigma Training managers to address power imbalances should be implemented |

| Toth et al. (2021), Canada [43] | >18 years of age, primary diagnosis of mental health problems (self-reported), obtained competitive employment within the last 12 weeks and able to communicate in English or French | Participants: n = 28 Age: M = 37.79, SD = 11.29 Age range: 22–59 Gender: female 57.1%, male 42.8% | Semi-structured interviews Thematic content analysis | Goals and conditions/context important antecedents for disclosure decisions Participants reported a psychological and physical release after disclosure, described as decrease of pressure/cognitive load Majority who disclosed perceived receiving a positive response from their supervisor, provided hope Fear of negative responses confirms there is still work to be done |

| Waugh et al. (2017), UK [44] | NHS trust employees, both mental health and general health service employees | Participants: n = 24 Age: 18–60 Gender: females 66.6%, males 33.3% | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | Personal experiences with people with mental health problems helped change attitudes Perceived stigmatising views of mental ill health in other staff members Hypothetical factors affected disclosure decisions Attitudes towards disclosure—risks and concerns for potential of discrimination or stigma Support after disclosure—managers generally described as helpful and supportive One unique factor of non-mental health professionals was mental ill health not talked about at work |

| Quantitative Studies | ||||

| Brennan et al. (2019), Australia [45] | Health professionals with long-term conditions | Participants: (n = 614), subset analysis (n = 545) Age: not reported Gender: not reported | Survey frequency, descriptive and inferential statistical analysis | Self-disclosure decisions are multifactorial: age, gender, workplace circumstances and nature of health condition Medical professionals less likely than nurses and allied health workers to disclose to colleagues People with mental health problems more cautious and selective in disclosing and more likely to disclose to supervisors than to colleagues |

| Cohen et al. (2016), UK [46] | Qualified doctors, regardless of whether or not they had experienced mental ill health | Participants: n = 1954 Age: 18–>65 Gender: female 60% | Survey Cross-sectional analysis | Younger doctors less likely to disclose than general practitioners and consultants Concerns about being labelled, confidentiality and not understanding the support structures available identified as obstacles to disclosure Doctors likely to disclose mental health problems later than they anticipated |

| Dewa et al. (2014), Canada [47] | >18 years, living in Ontario with workforce participation during 12 months prior | Participants: n = 2219 Age: <30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–64, and >65 Gender: female 63.8%, male 36.0% | Survey or telephone questionnaire Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), X2test | Although critical for workers who experience a mental health problem and find work challenging, a significant proportion do not seek support Fear of negative repercussions a barrier to disclosure One third would not tell managers if they experienced mental health problems 50% of workers identified that improving policies and practices would encourage disclosure 35% identified a combination of factors as important to encouraging disclosure: workplace relationships, supportive colleagues and good practices and policies Most pervasive reasons for concerns about a colleague with a mental health problem included safety and colleague’s reliability |

| Marshall et al. (2021), Australia [48] | Police officers who participated in a mental health screening program (and aware that individuals reporting significant levels of symptoms may be offered a follow-up assessment and counselling) | Participants: n = 90 Age: M age 44.1 years (SD = 9.3) Gender: female 31.1%, male 68.8% | Cross-sectional survey Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) for symptoms of psychological distress, abbreviated version of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) for symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), paired sample t-tests, independent sample t-tests | Employees under-reported symptoms when completing screening administered by their employer Under-reporting occurred regardless of gender and symptom type Senior staff and those with the most severe post-traumatic stress disorder and common mental health symptoms more likely to under-report Employer-administered mental health screening is not able to accurately capture all mental health problems |

| Stuart, H. (2017), Canada [49] | Front-line police officers who attended a one-day mental health workshop | Participants: n = 133 Age: not reported Gender: not reported | Pre-workshop surveys and post-workshop validity checking Psychometric analysis using 12-item Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination scale | Police-to-police mental health stigma may be a strong feature of police culture Police should be a focus for targeted anti-stigma interventions Police Office Stigma Scale may provide important insights into the nature and functioning of police-to-police stigma in police cultures in future research |

| Tay et al. (2018), UK [50] | Qualified clinical psychologists living in the UK | Participants: n = 678 Age: 84.2% 30–59 Gender: female 82.1%, male 17.8% | Survey The Social Distance Scale (SDS), nine-item Stig-9, 10-item self-stigma subscale of the Military Stigma Scale (MSS), nine-item Secrecy Scale, 10-item Attitudes towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale—Short Form, Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, One-way ANOVA and independent samples t-tests | Two-thirds had experienced mental health problems Perceived mental health stigma higher than external and self-stigma Participants more likely to have disclosed in their social domains than at work Negative consequences for self and career and shame prevented some from disclosing and seeking help |

| White et al. (2018), UK [51] | Psychiatrists working in the West Midlands region | Participants: n = 370 Age: not reported Gender: not reported | Questionnaire X2 tests | Most reluctant to disclose to colleagues or professional organisations Choices regarding disclosure and treatment influenced by confidentiality concerns 66%, stigma 22%, and career implications 35%, rather than quality of care 16% |

| Mixed Methods Studies | ||||

| Boyd et al. (2016), USA [52] | Mental health professionals with mental health problems, employed by Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), in Veterans Health Administration (VHA), who had been meeting monthly | Participants: quantitative (n = 77) qualitative (n = 55) Age: not reported Gender: not reported | Survey Descriptive statistics and manual descriptive coding for qualitative data | Very few asked for accommodations Two-thirds had not disclosed to their patients Respondents disclosed to only 16% of their colleagues, and about one third had not disclosed to any colleagues Lived experience was an asset, whether or not disclosed Many are proud to stand up and be counted, others cited reasons to be cautious about disclosure |

| Follmer et al. (2021), USA [53] | 18 years of age or older, employed at least 20 h per week, previous formal diagnosis of depression | Participants: Study 1—n = 30 Study 2—n = 455 Study 3—n = 233 Age: Study 1: average age: 34 years; age range: (19–65 years) Study 2: not reported Study 3: not reported Gender: Study 1: female 73%, male 27% Study 2: not reported Study 3: female 73%, male 27% | In-depth phone interviews, survey Thematic analysis, approach and avoidance scales, multivariate analysis | Approach and avoidance motives influenced by multiple factors, including social support, stigma, and diversity climate MANCOVA results not significant, λ = 0.99, F(2, 219) = 1.37, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.01 and no significant differences in the reported means for engagement as a function of the decision to disclose (M = 4.26) or conceal (M = 4.29), presenteeism did not significantly varied as a function of disclosure (M = 2.91) or concealment (M = 2.73) |

| Marino et al. (2016), USA [54] | Individuals with lived experience | Participants: n = 117 qualitative: n = 35 quantitative n = 117 Age: Qualitative: M 47, SD 10.86, range 25–71 Quantitative: M 47, SD 12.27, range 21–71 Gender: Qualitative: female 52.4%, male 42.8%, transgender 2.8% Quantitative: female 70%, male 26.8%, transgender 0.2% | Semi-structured interviews, focus groups (in-person or by phone) and survey Analysis: Independent t tests, Pearson correlation, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) | Lived experience a resource to assist others with service delivery Lived experience foundational to building relationships with individuals in recovery Disclosure dependent on social context and perceptions of safety and power differentials Individuals concerned regarding exclusion and discrimination |

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Main Themes across All Studies

3.4. Qualitative Studies

3.4.1. Beliefs about Stigma and Discrimination

3.4.2. Workplace Factors, Supports and Accommodations

3.4.3. Identity Factors

3.4.4. Disclosure Process Factors: Timing and Targets for Disclosure

3.5. Quantitative Studies

3.5.1. Beliefs about Stigma and Discrimination

3.5.2. Workplace Factors, Supports and Accommodations

3.5.3. Identity Factors

3.5.4. The Disclosure Process: Timing and Targets for Disclosure

3.6. Mixed-Methods Studies

3.6.1. Beliefs about Stigma and Discrimination

3.6.2. Workplace Factors, Supports and Accommodations

3.6.3. The Disclosure Process: Timing and Targets for Disclosure

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Qualitative Studies | Yes | No | Undetermined | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | |||

| 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | |||

| 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | [29,30,31,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | [32,33,34] | Only one author analysed the data [32]; does not state how many authors conducted the analysis [33]; not reported in the limitations [32,33,34] | |

| 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | |||

| 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | |||

| Quantitative Studies | Yes | No | Undetermined | Comments |

| 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question | [45,46,47,48,50,51] | [49] | Does not provide enough information | |

| 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | [45,46,50,51] | [47,48] | [49] | Sample not representative of target population [47]; low response rate [48]; does not state if sample is representative [49] |

| 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | [45,46,47,48,49,50,51] | |||

| 4.4. Is the risk of non-response bias low? | [49,51] | [46] | [45,47,48,50] | Information not provided [45,46,47,48] and self-selection and non-responses may have biased results [50]; high non-response rate with less than 1% of UK doctors responding [46] |

| 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | [45,46,47,48,49,50,51] | |||

| Mixed-Methods Studies | Yes | No | Undetermined | Comments |

| 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed-methods design to address the research question? | [52,53,54] | |||

| 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | [52,53,54] | |||

| 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | [52,53,54] | |||

| 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | [52,53,54] | |||

| 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | [52,53,54] |

References

- World Health Organisation. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Arensman, E.; Scott, V.; De Leo, D.; Pirkis, J. Suicide and Suicide Prevention From a Global Perspective. Crisis 2020, 41 (Suppl. 1), S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A.; Gunnell, D.; O’Connor, R.C.; Oquendo, M.A.; Pirkis, J.; Stanley, B.H. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J.; Gunnell, D.; Hawton, K.; Hetrick, S.; Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Sinyor, M.; Yip, P.S.F.; Robinson, J. A Public Health, Whole-of-Government Approach to National Suicide Prevention Strategies. Crisis 2023, 44, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roses in the Ocean Lived Experience of Suicide Definition. Available online: https://rosesintheocean.com.au/lived-experience-of-suicide/what-is-lived-experience/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Zamir, A.; Tickle, A.; Sabin-Farrell, R. A systematic review of the evidence relating to disclosure of psychological distress by mental health professionals within the workplace. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 1712–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohan, E.; Henderson, C.; Wheat, K.; Malcolm, E.; Clement, S.; Barley, E.A.; Slade, M.; Thornicroft, G. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C. Conceptualizing-stigma. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, L.; Oexle, N.; Dubke, R.; Wan, H.T.; Corrigan, P.W. The Self-Stigma of Suicide Attempt Survivors. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudoir, S.R.; Fisher, J.D. The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastuti, R.; Timming, A.R. An inter-disciplinary review of the literature on mental illness disclosure in the workplace: Implications for human resource management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 3302–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulginiti, A.; Pahwa, R.; Frey, L.M.; Rice, E.; Brekke, J.S. What Factors Influence the Decision to Share Suicidal Thoughts? A Multilevel Social Network Analysis of Disclosure Among Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2016, 46, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, C.S.; van Weeghel, J.; Joosen, M.C.W.; Gronholm, P.C.; Brouwers, E.P.M. Workers’ Decisions to Disclose a Mental Health Issue to Managers and the Consequences. Front. Psychiatr. 2021, 12, 631032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reavley, N.J.; Morgan, A.J.; Jorm, A.F. Disclosure of mental health problems: Findings from an Australian national survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brohan, E.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Henderson, C.; Murray, J.; Slade, M.; Thornicroft, G. Disclosure of a mental health problem in the employment context: Qualitative study of beliefs and experiences. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2014, 23, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; International Labour Organization. Mental Health at Work-Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oexle, N.; Puschner, N.; Votruba, N.; Rusch, N.; Mayer, L. Perceived Determinants of Disclosing Suicide Loss. Crisis 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clair, J.A.; Beatty, J.E.; Maclean, T.L. Out of sigh but not out of mind: Managing invisible social identities in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawgood, J.; Rimkeviciene, J.; Gibson, M.; McGrath, M.; Edwards, B.; Ross, V.; Kresin, T.; Kolves, K. Informing and Sustaining Participation of Lived Experience in the Suicide Prevention Workforce. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. Fostering social connection in the workplace. Am. J. Health Promot. 2011, 32, 219–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, P.J. Taking care of staff: A comprehensive model of support for paramedics and emergency medical dispatchers. Traumatology 2011, 17, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.; Sandborg, C. Supporting Peer Supporters. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2022, 48, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.; White, H.; Bath-Hextall, F.; Salmond, S.; Apostolo, J.; Kirkpatrick, P. A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagnais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, F.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisla Tool (MMAT) Version 2018: User Guide; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaers, R.; Geuze, E.; van Weeghel, J.; Leijten, F.; Rusch, N.; van de Mheen, D.; Varis, P.; Rozema, A.; Brouwers, E. Decision (not) to disclose mental health conditions or substance abuse in the work environment: A multiperspective focus group study within the military. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, E.P.M.; Joosen, M.C.W.; van Zelst, C.; Van Weeghel, J. To Disclose or Not to Disclose: A Multi-stakeholder Focus Group Study on Mental Health Issues in the Work Environment. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; Ragsdale, J.M. Mental health professionals with mental illnesses: A qualitative interview study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elraz, H. Identity, mental health and work: How employees with mental health conditions recount stigma and the pejorative discourse of mental illness. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 722–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, T.; McMillan, M.; Hazelton, M. The workplace and nurses with a mental illness. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 18, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.J.; Fortune, T.L.; Byrne, L.; Brophy, L.M. Supporting the Sharing of Mental Health Challenges in the Workplace: Findings from Comparative Case Study Research at Two Mental Health Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyhne, C.N.; Nielsen, C.V.; Kristiansen, S.T.; Bjerrum, M.B. ‘Work is a motivator in life’ Strategies in managing work participation among highly educated employees with depression. Work 2021, 69, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.; Currey, N.; Collings, S. “You don’t look like one of them”: Disclosure of mental illness in the workplace as an ongoing dilemma. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2011, 35, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, D.; Gordon, S.; Neale, J. It can work: Open employment for people with experience of mental illness. Work 2017, 56, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangarajan, S.K.; Muliyala, K.P.; Jadhav, P.; Philip, S.; Angothu, H.; Thirthalli, J. Reasonable Accommodation at the Workplace for Professionals with Severe Mental Illness: A Qualitative Study of Needs. Indian J. 2020, 42, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusch, N.; Rose, C.; Holzhausen, F.; Mulfinger, N.; Krumm, S.; Corrigan, P.W.; Willmund, G.D.; Zimmermann, P. Attitudes towards disclosing a mental illness among German soldiers and their comrades. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 258, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.A.; Sawyer, K.B. “We don’t talk about feelings or struggles like that”: White men’s experiences of eating disorders in the workplace. Psychol. Men Masc. 2020, 21, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, E.; Einboden, R.; Ryan, R.; Choi, I.; Harvey, S.B.; Glozier, N. Deciding to Disclose a Mental Health Condition in Male Dominated Workplaces; A Focus-Group Study. Front. Psychiatr. 2018, 9, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, K.E.; Dewa, C.S. Employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2014, 24, 732–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, K.E.; Yvon, F.; Villotti, P.; Lecomte, T.; Lachance, J.P.; Kirsh, B.; Stuart, H.; Berbiche, D.; Corbiere, M. Disclosure dilemmas: How people with a mental health condition perceive and manage disclosure at work. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 44, 7791–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, W.; Lethem, C.; Sherring, S.; Henderson, C. Exploring experiences of and attitudes towards mental illness and disclosure amongst health care professionals: A qualitative study. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, D.; Lindsay, D.; Holmes, C.; Smyth, W. Conceal or reveal? Patterns of self-disclosure of long-term conditions at work by health professionals in a large regional Australian health service. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2019, 12, 339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.; Winstanley, S.J.; Greene, G. Understanding doctors’ attitudes towards self-disclosure of mental ill health. Occup. Med. 2016, 66, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewa, C.S. Worker attitudes towards mental health problems and disclosure. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 5, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marshall, R.E.; Milligan-Saville, J.; Petrie, K.; Bryant, R.A.; Mitchell, P.B.; Harvey, S.B. Mental health screening amongst police officers: Factors associated with under-reporting of symptoms. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, H. Mental Illness Stigma Expressed by Police to Police. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2017, 54, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, S.; Alcock, K.; Scior, K. Mental health problems among clinical psychologists: Stigma and its impact on disclosure and help-seeking. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Shiralkar, P.; Hassan, T.; Galbraith, N.; Callaghan, R. Barriers to mental healthcare for psychiatrists. Psychiatr. Bull. 2018, 30, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.E.; Zeiss, A.; Reddy, S.; Skinner, S. Accomplishments of 77 VA mental health professionals with a lived experience of mental illness. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2016, 86, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmer, K.B.; Jones, K.S. It’s not what you do, it’s why you do it: Motives for disclosure and concealment decisions among employees with depression. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 1013–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.K.; Child, B.; Campbell Krasinski, V. Sharing Experience Learned Firsthand (SELF): Self-disclosure of lived experience in mental health services and supports. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2016, 39, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Rao, D. On the self-stigma of mental Illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavley, N.J.; Morgan, A.J.; Jorm, A.F. Predictors of experiences of discrimination and positive treatment in people with mental health problems: Findings from an Australian national survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, E.; Arnaert, A.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M. Healthcare professional disclosure of mental illness in the workplace: A rapid scoping review. J. Ment. Health 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, M.D.; Ihionvien, S.; Leduc, C.; Aust, B.; Amann, B.L.; Cresswell-Smith, J.; Reich, H.; Cully, G.; Sanches, S.; Fanaj, N.; et al. Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to reduce mental health related stigma in the workplace: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, K.S.; Cottrill, F.A.; Mackinnon, A.; Morgan, A.J.; Kelly, C.M.; Armstrong, G.; Kitchener, B.A.; Reavley, N.J.; Jorm, A.F. Effects of the Mental Health First Aid for the suicidal person course on beliefs about suicide, stigmatising attitudes, confidence to help, and intended and actual helping actions: An evaluation. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton, E.; Choi, I.; Calvo, R.; Hickie, I.; Henderson, C.; Harvey, S.B.; Glozier, N. Web-based decision aid tool for disclosure of a mental health condition in the workplace: A randomised controlled trial. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theme | Qualitative Studies | Quantitative | Mixed Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs about stigma and discrimination | [29,30,31,32,33,35,36,39,40,41,42,44] | [45,47,49,50,51] | [52,53,54] |

| Workplace factors (including supports and accommodations) | [29,30,33,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44] | [47,49] | [6,52] |

| Identity factors (including personal and professional identity, gender and intersectionality) | [29,32,33,34,35,39,40,41] | [45,46,48,50] | |

| Disclosure process factors (including timing and recipients) | [29,30,31,33,34,37,42,43,44] | [45,46,50] | [52,53,54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGrath, M.O.; Krysinska, K.; Reavley, N.J.; Andriessen, K.; Pirkis, J. Disclosure of Mental Health Problems or Suicidality at Work: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085548

McGrath MO, Krysinska K, Reavley NJ, Andriessen K, Pirkis J. Disclosure of Mental Health Problems or Suicidality at Work: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(8):5548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085548

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGrath, Martina O., Karolina Krysinska, Nicola J. Reavley, Karl Andriessen, and Jane Pirkis. 2023. "Disclosure of Mental Health Problems or Suicidality at Work: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 8: 5548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085548

APA StyleMcGrath, M. O., Krysinska, K., Reavley, N. J., Andriessen, K., & Pirkis, J. (2023). Disclosure of Mental Health Problems or Suicidality at Work: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(8), 5548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085548