Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour: A Case Study of Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- For which groups of Polish tourists did the COVID-19 pandemic become a factor limiting tourist activity?

- How often, when, and how long did the departures take place for?

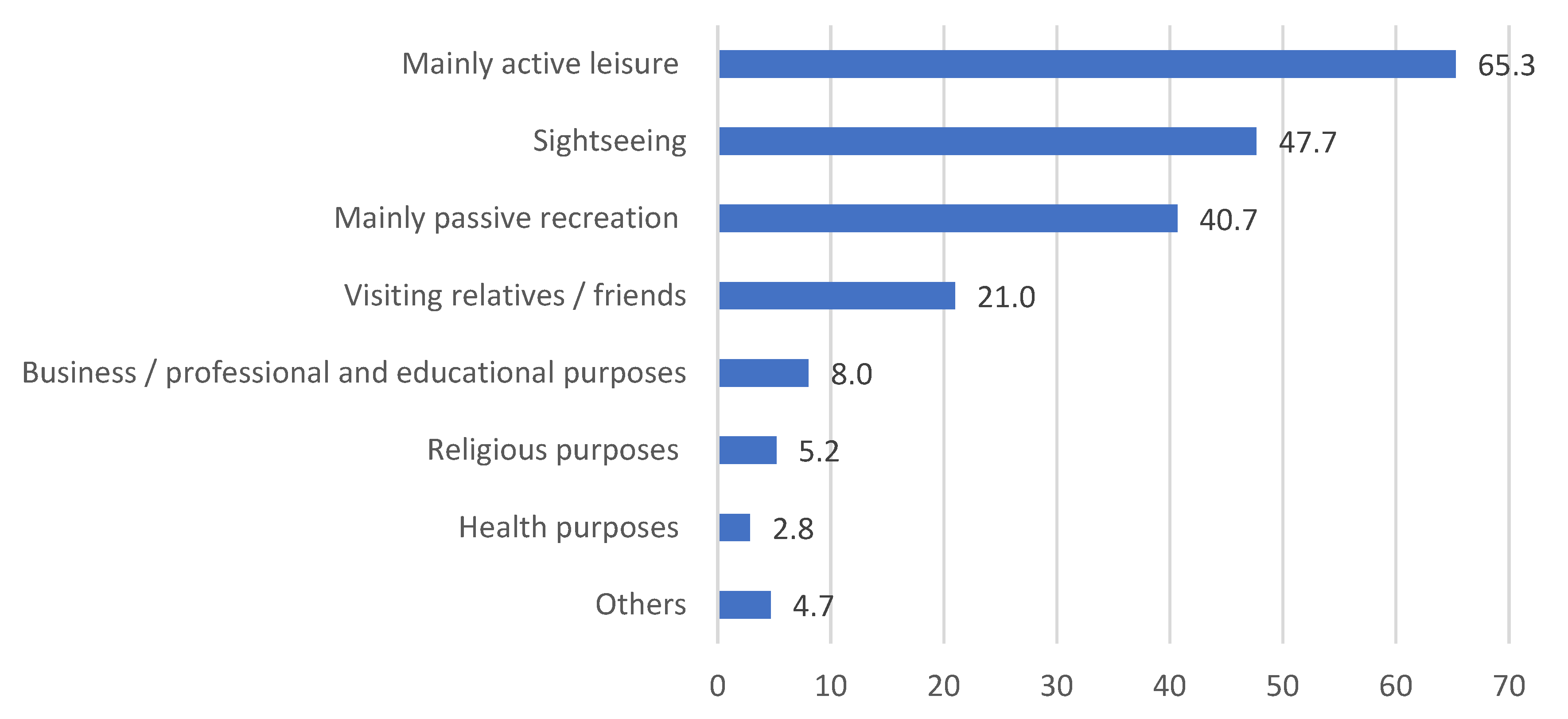

- What were the main goals and destinations of Polish tourists?

- What accommodation facilities did tourists use and how did they meet their nutritional needs?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism

- -

- Functional (risks related to the functions of the product/service);

- -

- Physical (safety concerns);

- -

- Economic (related to doubts about the price of the product/service);

- -

- Social (related to the acceptance of social groups, e.g., family, friends);

- -

- Psychological (related to the formation of one’s image, prestige, dignity, etc.).

- -

- Awareness of the need;

- -

- Search for information;

- -

- Evaluation of choice alternatives;

- -

- Purchase decision and purchase;

- -

- Feelings after purchase [34].

2.2. COVID-19 and Tourism

3. Research Method

4. Results of the Research

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The group of Polish tourists who, in the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, most often abandoned their planned tourist trips were elderly people, usually from rural areas, who feared both infection and organisational difficulties or increased travel costs (resulting from stricter sanitary requirements)—these tourists compensated for the lack of foreign trips with domestic stays;

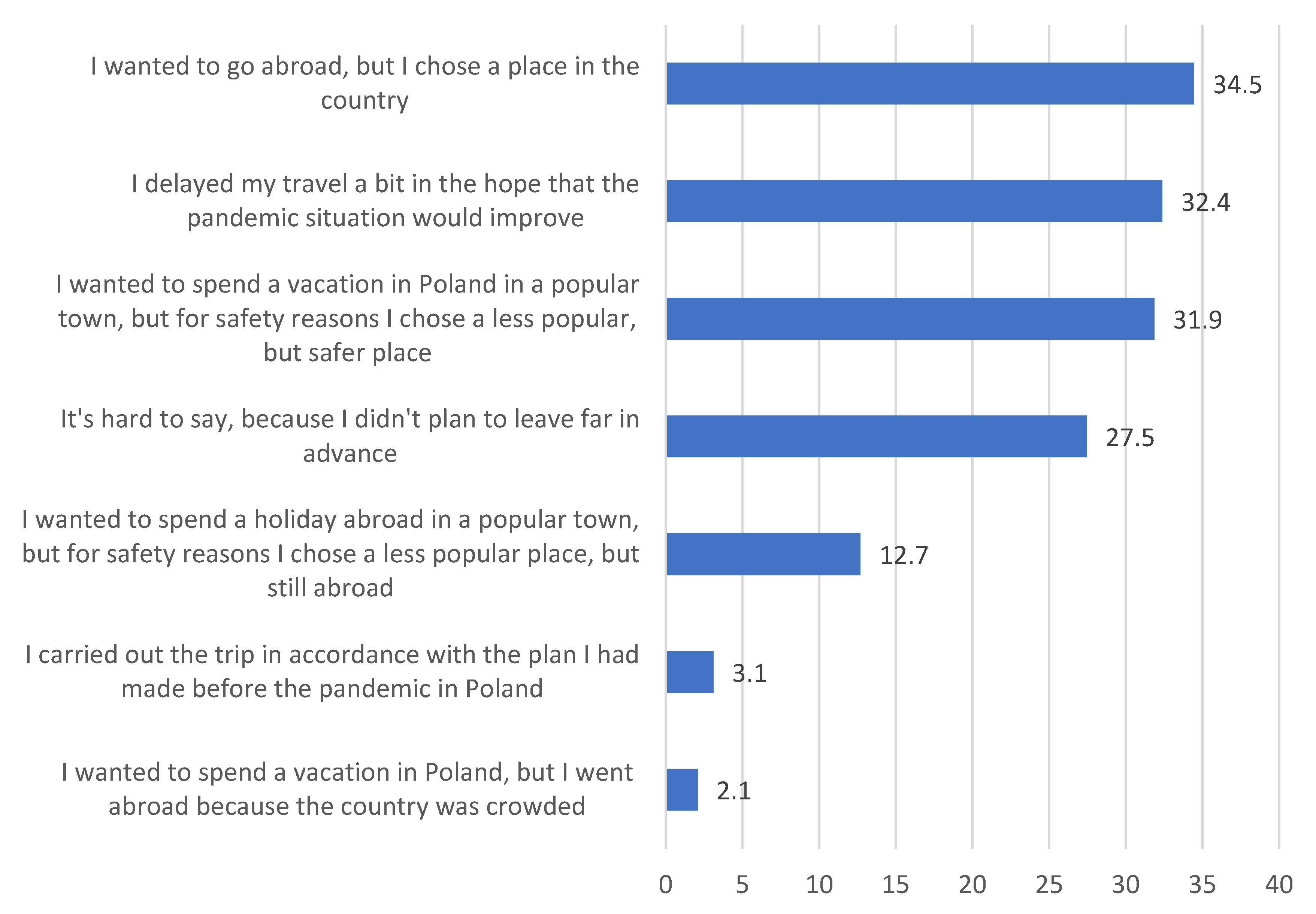

- Fears caused by the pandemic, and initially also contradictory information on its mechanisms, caused Polish tourists’ decisions to be influenced by factors such as the length of stay (a tendency to shorten trips), time of year (the possibility of staying outside as long as possible), and location (proven or reputable, usually close to the place of residence);

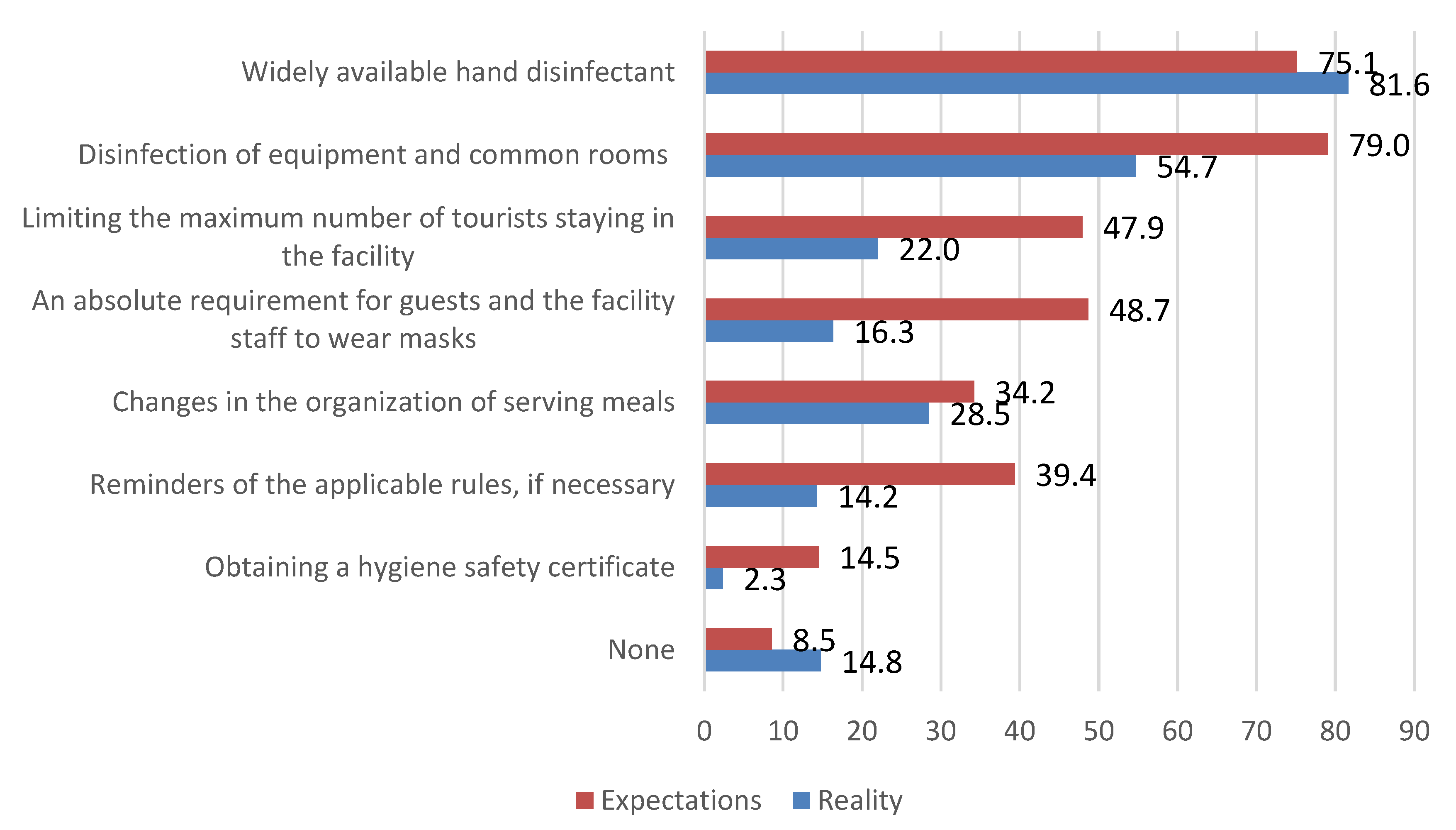

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, Polish tourists chose to travel in the company of members of their own families, using facilities allowing the recommended social distance, often deciding, for safety reasons, to prepare meals themselves in the selected accommodation (which was also an important factor in its selection).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wieczorek, K. Czynniki wpływające na aktywność turystyczną i wybór destynacji turystycznych wśród studentów. Stud. Ekon. 2020, 392, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Spojrzenie Turysty; Wydawnictwo PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Niemczyk, A. Zachowania Konsumentów na Rynku Turystycznym; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kordek, P. Analiza: Współczesna Turystyka Jako Stymulator Rozwoju Społeczno–Gospodarczego Państwa; Szkoła Wyższa im. Bogdana Jańskiego Wydział Zamiejscowy w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M.; Gussing Burgess, L.; Jones, A.; Ritchie, B.W. ‘No Ebola…still doomed’–The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-covid-19 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Lim, W.M. Toward an agency and reactance theory of crowding: Insights from COVID-19 and the tourism industry. J. Consum. Behaviour. 2021, 20, 1690–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Impact Assessment of the COVID-19 Outbreak on International Tourism. 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Devesa, M.; Laguna-Garcia, M.; Palacios, A. The role of motivation in visitor satisfaction: Empirical evidence in rural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratić, M.; Radivojević, A.; Stojiljković, N.; Simović, O.; Juvan, E.; Lesjak, M.; Podovšovnik, E. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Tourists’ COVID-19 Risk Perception and Vacation Behavior Shift. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.; Samitas, A.; Spyridou, A.E. Tourism demand and the COVID-19 pandemic: An LSTM approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, J.; Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The Influence of Islamic Religiosity on the Perceived Socio-Cultural Impact of Sustainable Tourism Development in Pakistan: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.R.; Sah, P.; Moghadas, S.M.; Pandey, A.; Shoukat, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meyers, L.A.; Singer, B.H.; Galvani, A.P. Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7504–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Bardia, S. COVID-19 and international travel restrictions: The geopolitics of health and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachniewska, M. Polaryzacja podaży turystycznej jako stymulanta rozwoju sieciowych produktów turystycznych. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2014, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R. Consumer Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrooke, J.; Horner, S. Consumer Behavior in Tourism; Elsevie: Burlington, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K. Marketing Management; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Enis, B. Marketing Principles: The Management Process; Goodyear Pub. Co.: Pacific Palisades, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Xue, F.; Khan, S.; Khatib, S.F.A. Consumer behaviour analysis for business development. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, S.; Leković, K.; Tadić, J. Consumer behaviour: The influence of age and family structure on the choice of activities in a tourist destination. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 32, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, A. Rola uwarunkowań psychologicznych w kształtowaniu zachowań konsumentów na rynku turystycznym—Wybrane aspekty. Probl. Zarządzania Finans. Mark. 2010, 16, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Wolska, A. Miejsce pochodzenia jako czynnik kształtujący zachowania konsumentów w turystyce na przykładzie mieszkańców Majorki. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2016, 35, 337–347. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, G.; Zhang, J.; Pabel, A.; Chen, N. Understanding the Factors Influencing the Leisure Tourism Behavior of Visually Impaired Travelers: An Empirical Study in China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 684285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechoczek, J. Transformacja koncepcji marketingowych przedsiębiorstw turystycznych pod wpływem zmian w zachowaniach konsumentów. Stud. Ekon. 2015, 215, 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, G. Czynniki kształtujące zachowania nabywców usług turystycznych na przykładzie badań rynku europejskiego. Ekon. Probl. Usług 2012, 84, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki, L. Wpływ cen na zachowanie konsumenta na rynku turystycznym. Zesz. Nauk. Małopolskiej Wyższej Szkoły Ekon. Tarn. 2008, 1, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, W.; Sandler, T.; Parise, G.F. An econometric analysis of the impact of terrorism on tourism. Kyklos 1992, 45, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakopoulou, I. Does health quality affect tourism? Evidence from system GMM estimates. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 73, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaciow, M. Międzynarodowe badania zachowań e-konsumentów-typy, podejścia, wymiary. Stud. Ekon. 2014, 187, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. International Tourism and Climate Change. Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, I. 2050—Tomorrow’s Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peszko, K. Instrumenty marketingu i ich wpływ na zachowania nabywców. In Zachowania Nabywców; Perenc, J., Rosa, G., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego: Szczecin, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Seventh European Edition; Pearson Education Limited: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Niezgoda, A.; Zmyślony, P. Popyt Turystyczny; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fratu, D. Factors of influence and changes in the tourism consumer behaviour. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Braşov 2011, 4, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, A.; Moschis, G.P.; Lee, E. Life events and brand preference changes. J. Consum. Behav. 2003, 3, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What Next? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Moschis, G.; Mathur, A. A. A Study of Life Events and Patronage Behavior. In Asia Pacific Advances in Consumer Research; Hung, K., Monroe, K.B., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1998; Volume 3, pp. 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, T.; Toohey, K. Perceptions of Terrorism Threats at the 2004 Olympic Games: Implications for Sport Events. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przecławski, K. Człowiek a Turystyka. Zarys Socjologii Turystyki; Albis: Kraków, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski, E. Wpływ aktywności turystycznej na równowagę duchową i zdrowie człowieka, Zeszyty Naukowe. Turystyka Rekreacja 2013, 2, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pelenc, J.; Bazile, D.; Ceruti, C. Collective capability and collective agency for sustainability: A case study. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 118, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, S. Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View; Harper and Row: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Matarazzo, M.; Diamantopoulos, A. Applying reactance theory to study consumer responses to COVID restrictions: A note on model specification. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanka, R.J.; Buff, C. COVID-19 Generation: A Conceptual Framework of the Consumer Behavioral Shifts to Be Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 33, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.; Scuderi, R. COVID-19 and the recovery of the tourism industry. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B. Towards and framework for tourism disaster management. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W. Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños-Pino, J.F.; Boto-García, D.; Del Valle, E.; Sustacha, I. The impact of COVID-19 on tourists’ length of stay and daily expenditures. Tour. Econ. 2023, 29, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, G.; Zheng, Y.; Domingos, S. Extreme natural and man-made events and human adaptive responses mediated by information and communication technologies’ use: A systematic literature review. Technol. Forecast. and Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kasozi, K.I.; Niedbała, G.; Alqarni, M.; Zirintunda, G.; Ssempijja, F.; Musinguzi, S.P.; Usman, I.M.; Matama, K.; Hetta, H.F.; Mbiydzenyuy, N.E.; et al. Bee Venom—A Potential Complementary Medicine Candidate for SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 594458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, L.; Komarkova, L.; Egerova, D.; Micík, M. The effect of COVID-19 on consumer shopping behaviour: Generational cohort perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Polyzos, S.; Huan, T.C. The good, the bad and the ugly on COVID-19 tourism recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofronov, B. The Development of the Travel and Tourism Industry in the World. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. 2018, 18, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Hall, C.M. Contemporary Tourism: An International Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.unwto.org/taxonomy/term/347 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Jaipuria, S.; Parida, R.; Ray, P. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism sector in India. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera-Kowalska, M.; Uglis, J.; Lira, J. A framework to measure the taxonomic of economic anchor: A case study of the Three Seas Initiative countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phama, T.D.; Dwyera, L.; Sua, J.-J.; Ngo, T. COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on Australian economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 88, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuuren, C.V.; Slabbert, E. Travel motivations and behaviour of tourists to a South African resort. Afr. J. Phys. Act. Health Sci. 2011, 17 Pt 1, 694–707. [Google Scholar]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: Use of the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Hum. Commun. Res. 2003, 29, 370–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, J.; Morrison, A.M. Developing a Scale to Measure Tourist Perceived Safety. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 1232–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ. Behav. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasion, R.; Paiva, T.O.; Fernandes, C.; Barbosa, F. The AGE effect on protective behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak: Sociodemographic, perceptions and psychological accounts. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Dai, S.; Xu, H. Predicting tourists’ health risk preventative behaviour and travelling satisfaction in Tibet: Combining the theory of planned behaviour and health belief model. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Niedziółka, A.; Krasnodębski, A. Respondents’ Involvement in Tourist Activities at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balińska, A.; Olejniczak, W. Experiences of Polish Tourists Traveling for Leisure Purposes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uglis, J.; Jęczmyk, A.; Zawadka, J.; Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.M.; Pszczoła, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourist plans: A case study from Poland. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, G.R.; Lee, H.C.; Lim, R.S.; Fullerton, J. Recruitment of hard-toreach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs. Health Sci. 2010, 12, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, M.C. Using the Snowball Method in Marketing Research on Hidden Populations. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2011, 1, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Naderifar, M.; Goli, H.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 2017, 14, e67670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Coronavirus impacts on post-pandemic travel behaviours. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uglis, J.; Krysińska, B. Próba zdefiniowania profilu agroturysty. Probl. Usług 2012, 84, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.I.; Chen, C.C.; Tseng, W.C.; Ju, L.F.; Huang, B.W. Assessing impacts of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, S.; Geerts, W.; Wang, H. The Travel Industry Turned Upside Down: Insights, Analysis, and Actions for Travel Executives. McKinsey and Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/the-travel-industry-turned-upside-down-insights-analysis-and-actions-for-travel-executives (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Dušek, R.; Sagapova, N. Effect of the COVID-19 global pandemic on tourists’ preferences and marketing mix ofaccommodation facilities—Case study from Czech Republic. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 92, 01009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H. COVID-19: An opportunity to review existing grounded theories in event studies. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2021, 22, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, I.L. COVID-19: How can travel medicine benefit from tourism’s focus on people during a pandemic? Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccine 2022, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazneen, S.; Hong, X.; Din, N.U. COVID-19 Crises and Tourist Travel Risk Perceptions. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orîndaru, A.; Popescu, M.-F.; Alexoaei, A.; Căescu, Ș.-C.; Florescu, M.; Orzan, A.-O. Tourism in a Post-COVID-19 Era: Sustainable Strategies for Industry’s Recovery. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, O. To Recovery & Beyond. The Future of Travel & Tourism in the Wake of COVID-19. World Travel & Tourism Council, September 2020. Available online: https://www.oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/v2/publications/2020/To_Recovery_and_Beyond-The_Future_of_Travel_and_Tourism_in_the_Wake_of_COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Luo, J.M.; Lam, C.F. Travel Anxiety, Risk Attitude and Travel Intentions towards “Travel Bubble” Destinations in Hong Kong: Effect of the Fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.waszaturystyka.pl/not-vacations-but-shorter-spontaneous-trips-poles-travel-plans-for-summer-2021/ (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Chung-Shing, C. Developing a Conceptual Model for the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Changing Tourism Risk Perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Fusté-Forné, F. Post-Pandemic Recovery: A Case of Domestic Tourism in Akaroa (South Island, New Zealand). World 2021, 2, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Xu, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.-K.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ perceived risk, emotional solidarity, and support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, I.Q. Key Consumer Behavior Thresholds Identified as the Coronavirus Outbreak Evolves. 2020. Available online: https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/analysis/2020/key-consumer-behavior-thresholds-identified-as-the-coronavirus-outbreak-evolves-2/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Rastegar, R.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Ruhane, L. COVID-19 and a justice framework to guide tourism recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Wen, L.; Liu, C. Forecasting tourism recovery amid COVID-19. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Economic | Non-Economic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| outside | inside | psychological | personal– demographic | social–cultural: | others |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Characteristic | Individuals Participating in Tourism Activities n = 386 | Individuals not Participating in Tourism Activities n = 123 |

|---|---|---|

| (in %) | ||

| Gender | ||

| female | 58.3 | 56.1 |

| male | 41.7 | 43.9 |

| Education | ||

| basic vocational or lower education | 2.1 | 4.1 |

| upper secondary education | 26.9 | 33.3 |

| higher education | 71.0 | 62.6 |

| Assessment of one’s own material situation | ||

| very good | 14.3 | 14.6 |

| good | 61.4 | 52.0 |

| bearable | 23.8 | 30.1 |

| poor and very poor | 0.5 | 3.3 |

| The impact of the pandemic on the respondents’ financial situations | ||

| remained unchanged | 58.0 | 51.2 |

| deteriorated | 29.8 | 36.6 |

| improved | 3.9 | 3.3 |

| hard to say | 8.3 | 8.9 |

| Place of residence | ||

| rural area | 28.2 | 46.3 |

| city with up to 50,000 inhab. | 18.7 | 19.5 |

| city with 50,000–100,000 inhab. | 12.7 | 4.9 |

| city with over 100,000 inhab. | 40.4 | 29.3 |

| Children (below 18) in a household | ||

| household without children | 61.7 | 68.3 |

| household with children | 38.3 | 31.7 |

| Age | ||

| up to 29 | 27.2 | 10.5 |

| 30–39 | 31.9 | 28.5 |

| 40–49 | 26.2 | 29.3 |

| 50 and more | 14.7 | 31.7 |

| (number of years) | ||

| the average age | 38.0 | 44.9 |

| the median age | 37 | 44 |

| Reason | Not Important | Slightly Important | Moderately Important | Very Important | Average (a Scale of 1–4) | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (in %) | ||||||

| The pandemic, fear of coronavirus infection | 4.1 | 8.9 | 26.0 | 61.0 | 3.44 | 0.82 |

| Lack of time | 24.4 | 30.9 | 30.1 | 14.6 | 2.35 | 1.01 |

| Official and occupational obligations | 30.9 | 30.1 | 26.0 | 13.0 | 2.21 | 1.03 |

| No need/desire to leave | 34.1 | 26.0 | 26.0 | 13.8 | 2.20 | 1.06 |

| I prefer to relax where I live | 34.1 | 25.2 | 28.5 | 12.2 | 2.19 | 1.04 |

| Insufficient funds for such trip | 35.0 | 29.3 | 18.7 | 17.1 | 2.18 | 1.09 |

| Household duties | 30.1 | 38.2 | 18.7 | 13.0 | 2.15 | 1.00 |

| Inability to book an accommodation facility on the preferred date | 40.7 | 31.7 | 15.4 | 12.2 | 1.99 | 1.03 |

| Organisation issues | 48.8 | 27.6 | 13.0 | 10.6 | 1.85 | 1.01 |

| No suitable offer | 46.3 | 32.5 | 16.3 | 4.9 | 1.80 | 0.89 |

| Impossible due to health condition | 56.1 | 26.0 | 13.8 | 4.1 | 1.66 | 0.87 |

| No company | 54.5 | 30.9 | 8.9 | 5.7 | 1.66 | 0.87 |

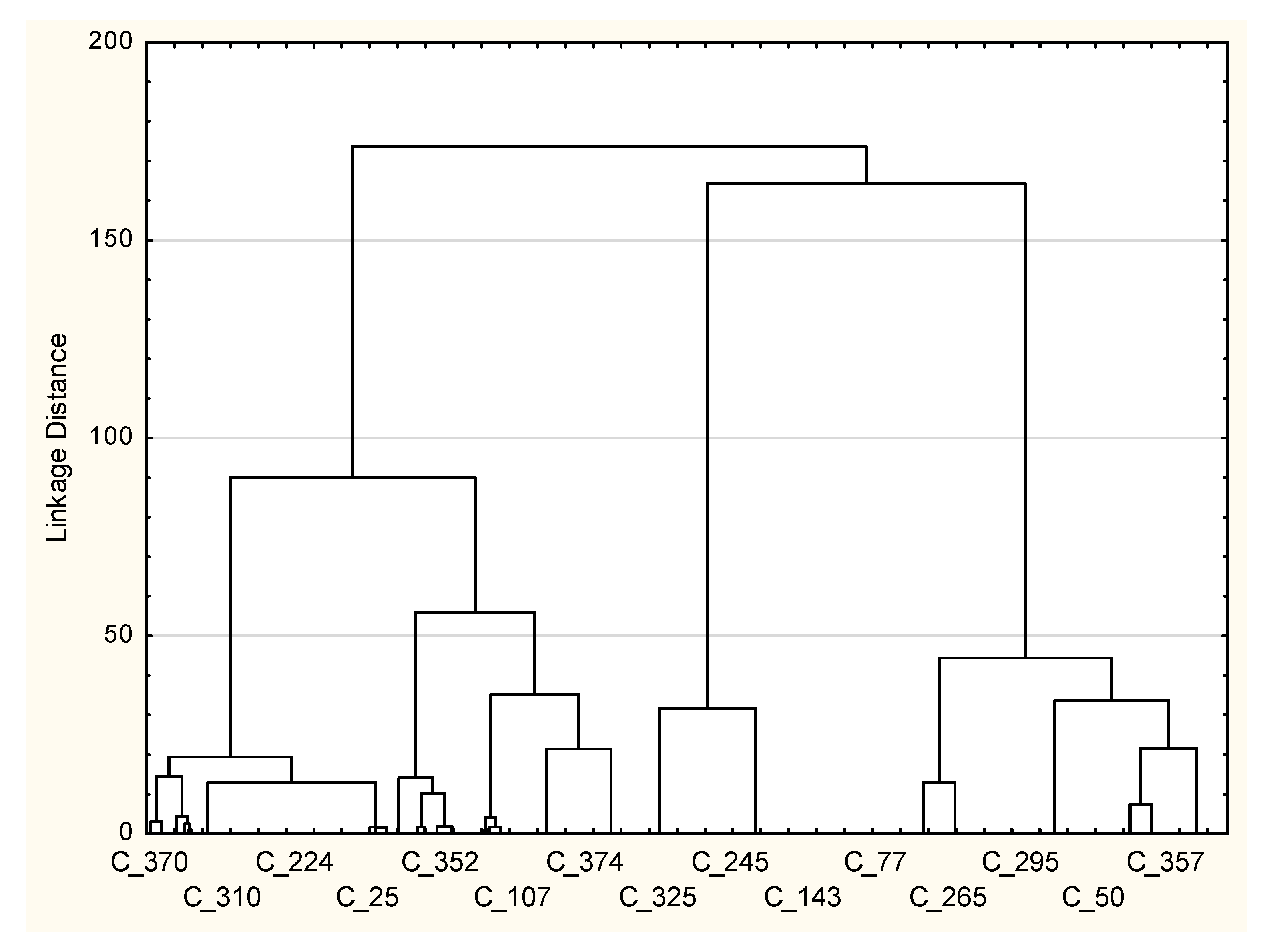

| Variables | Cluster 1 n = 178 | Cluster 2 n = 96 | Cluster 3 n = 112 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Female | Female |

| (χ2 = 1.74; p = 0.419) | (61.8%) | (52.8%) | (54.5%) |

| Level of education | Higher education | Higher education | Higher education |

| (χ2 = 3.86; p = 0.145) | (66.8%) | (78.1%) | (71.4%) |

| Assessment of one’s own material situation | Good | Good | Good |

| (χ2 = 14.77; p = 0.005) * | (56.7%) | (71.9%) | (59.8%) |

| Age | 30–39 | 40–49 | 30–39 |

| (χ2 = 8.67; p = 0.193) | (30.9%) | (33.3%) | (32.1%) |

| Percentage of Facility Visitors Among the Respondents | Epidemiological Safety Rating of the Facility (on a Scale of 1 to 5) | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hotel or holiday resort | 46.1 | 2.79 | 1.03 |

| Rented apartment | 36.5 | 4.15 | 0.72 |

| Agritourism farm | 27.5 | 3.70 | 0.79 |

| Rented house/holiday cabin | 22.3 | 4.27 | 0.82 |

| Private accommodation—rented room | 20.5 | 3.48 | 0.94 |

| Overnight stay with family/friends | 16.8 | 3.87 | 0.99 |

| Guesthouse | 11.4 | 3.14 | 0.89 |

| Camping site (a tent, a caravan) | 7.5 | 4.06 | 0.91 |

| “Squatting” in a tent, caravan | 4.4 | 4.61 | 0.77 |

| Owning a holiday cabin/second home | 3.9 | 4.89 | 0.36 |

| Not Important | Slightly Important | Moderately Important | Very Important | Average on a Scale of 1 to 4 | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (in %) | ||||||

| Individuals who refused to adhere to mask and social distancing requirements | 10.9 | 14.2 | 27.5 | 42.7 | 3.07 | 1.03 |

| Discomfort caused by the introduction of sanitary–epidemiological restrictions in tourist facilities | 10.1 | 25.1 | 32.4 | 29.0 | 2.83 | 0.98 |

| Overtourism | 17.4 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 35.0 | 2.79 | 1.15 |

| Fear of coronavirus infection | 12.2 | 25.6 | 30.8 | 27.5 | 2.77 | 1.00 |

| Reduced number of tourist attractions in the destination | 16.3 | 25.9 | 24.4 | 27.2 | 2.67 | 1.07 |

| Increased prices of tourism services | 12.7 | 28 | 27.5 | 20.5 | 2.63 | 0.99 |

| Limited infrastructure and recreational equipment at the accommodation facility | 22.5 | 27.5 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 2.41 | 1.09 |

| Reduced number of attractions and leisure activities offered by the accommodation facility | 23.8 | 26.4 | 21.2 | 18.1 | 2.38 | 1.08 |

| Very few tourists—I like meeting new people | 47.4 | 22.5 | 10.9 | 4.7 | 1.68 | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jęczmyk, A.; Uglis, J.; Zawadka, J.; Pietrzak-Zawadka, J.; Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.M.; Kozera-Kowalska, M. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour: A Case Study of Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085545

Jęczmyk A, Uglis J, Zawadka J, Pietrzak-Zawadka J, Wojcieszak-Zbierska MM, Kozera-Kowalska M. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour: A Case Study of Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(8):5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085545

Chicago/Turabian StyleJęczmyk, Anna, Jarosław Uglis, Jan Zawadka, Joanna Pietrzak-Zawadka, Monika Małgorzata Wojcieszak-Zbierska, and Magdalena Kozera-Kowalska. 2023. "Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour: A Case Study of Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 8: 5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085545

APA StyleJęczmyk, A., Uglis, J., Zawadka, J., Pietrzak-Zawadka, J., Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M. M., & Kozera-Kowalska, M. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour: A Case Study of Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(8), 5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085545