Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Perceived Barriers for the Compliance of Standard Precautions among Medical and Nursing Students in Central India

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objectives

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- An all-inclusive approach was adopted for data collection from the students enrolled in R.D. Gardi Medical College and R. D. Gardi College of Nursing.

- The students who attended scheduled clinical postings as per the medical and nursing curricula and had direct contact with the patients (MBBS students in the second year onward).

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Students who were not willing to participate or who did not give written consent for participation.

- First-year MBBS students (due to non-exposure to the clinical area).

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Collection Tool

2.4. Methodological Considerations

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

2.6. Ethics Statement

3. Results

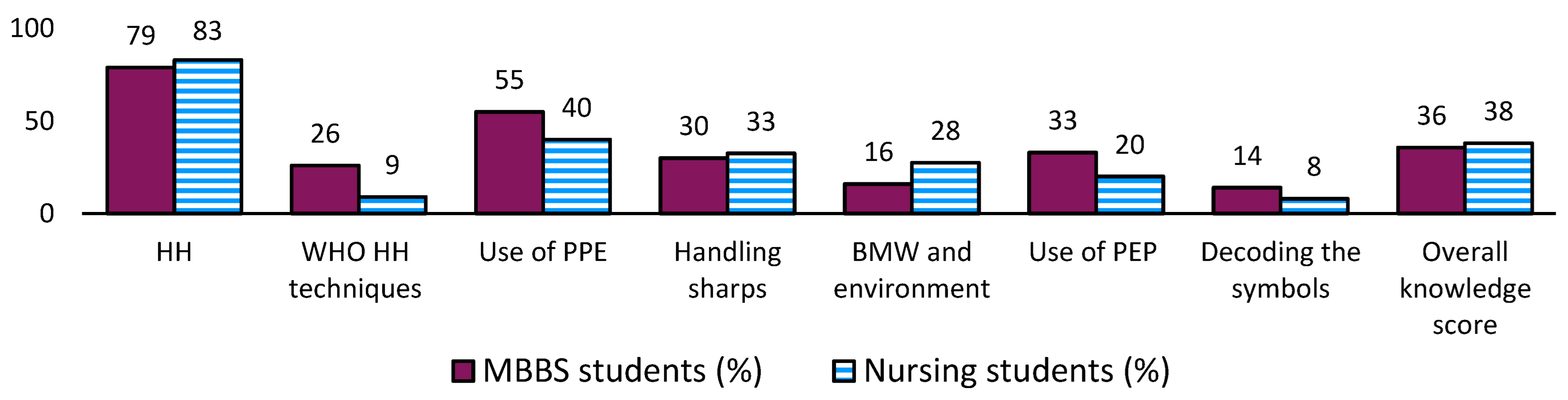

3.1. Knowledge about Standard Precautions and Preventive Measures

3.2. Attitudes toward the Use of SPs

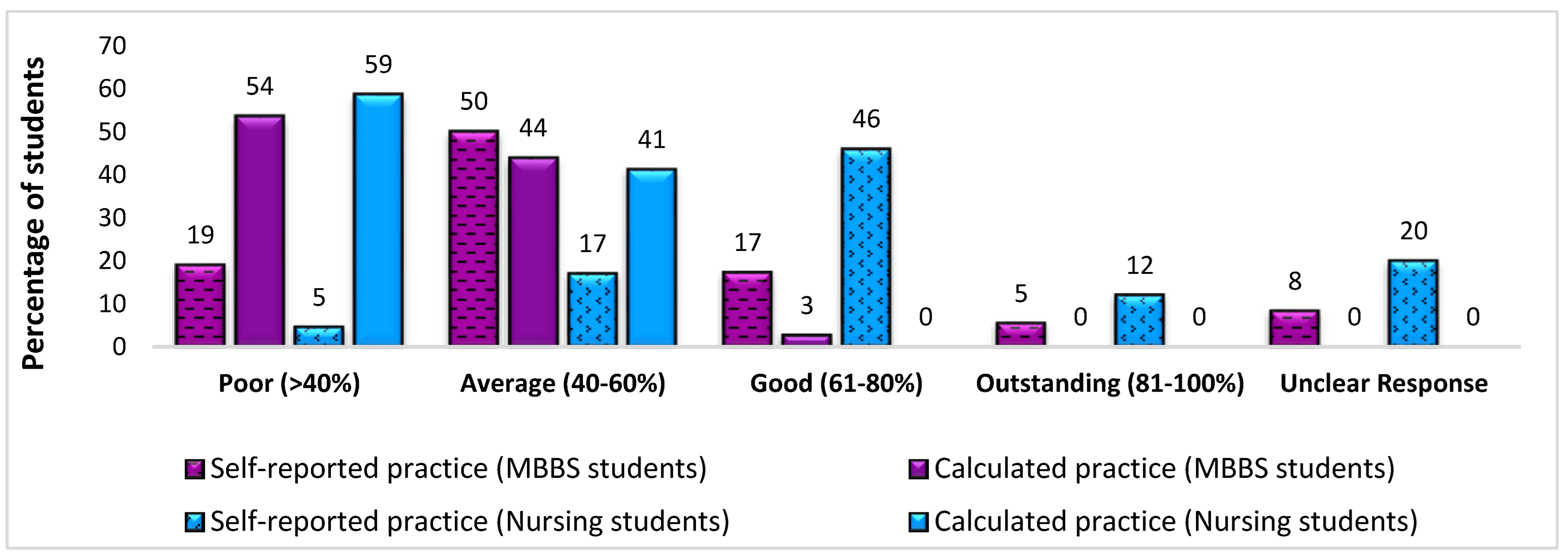

3.3. Practice of SPs

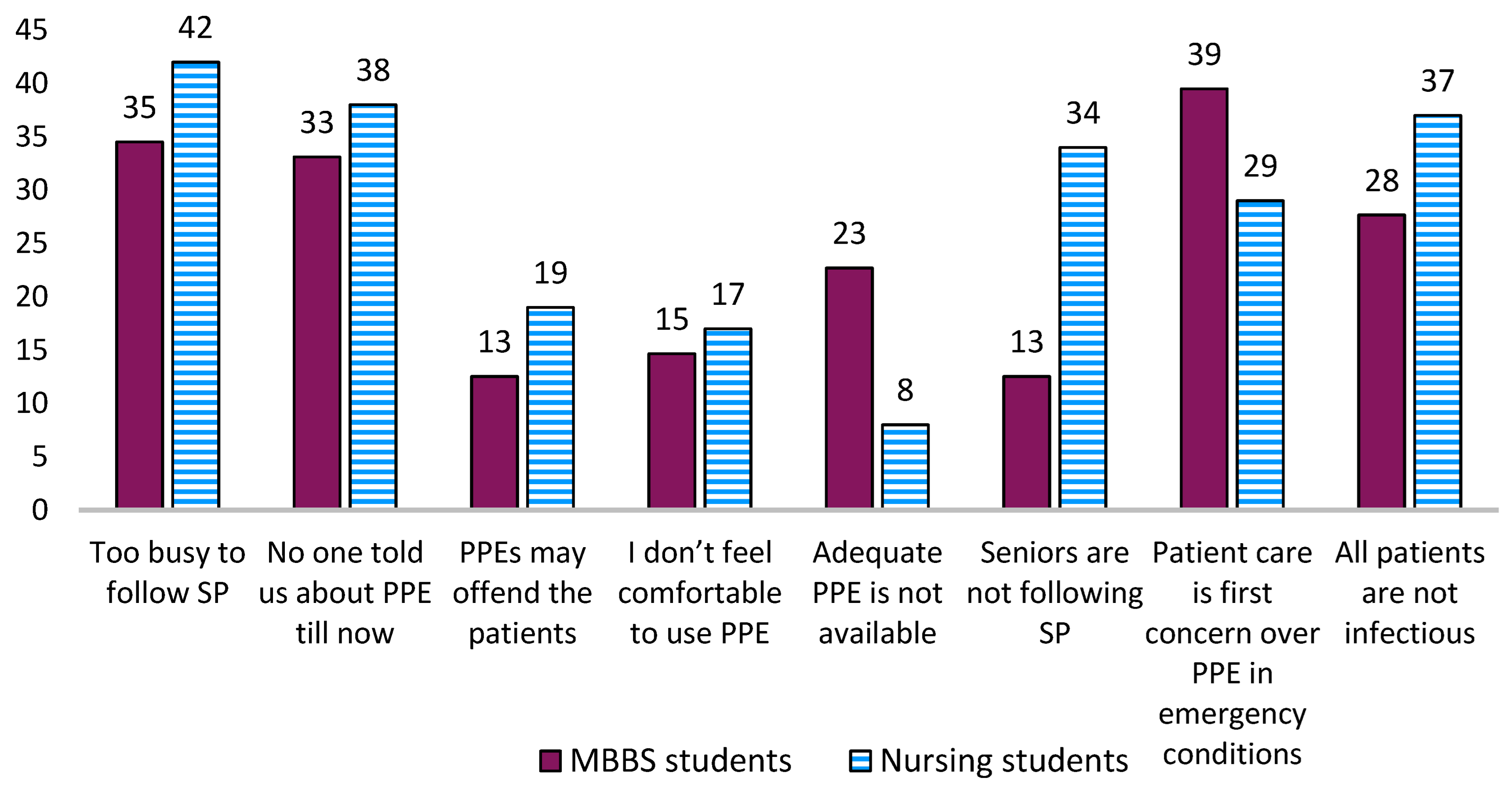

3.4. Perceived Barriers Underlying Noncompliance with SPs

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collins, A.S. Preventing Health Care–Associated Infections. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Hughes, R.G., Ed.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008; Chapter 41. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2683/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Revelas, A. Healthcare-associated infections: A public health problem. Niger. Med. J. 2012, 53, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Occupational Infections. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/occupational-hazards-in-health-sector/occupational-infections#:~:text=The%20most%20common%20occupational%20infections,infections%20(coronaviruses%2C%20influenza) (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Zingg, W.; Holmes, A.; Dettenkofer, M.; Goetting, T.; Secci, F.; Clack, L.; Allegranzi, B.; Magiorakos, A.P.; Pittet, D. Systematic review and evidence-based guidance on organization of hospital infection control programmes (SIGHT) study group. Hospital organisation, management, and structure for prevention of health-care-associated infection: A systematic review and expert consensus. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 15, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankam, H.K.; Van Loon, Y.T.; De Boer, M.G.J.; Van Der Bij, W.; Willemsen, S.P.; Troost, J.P. Surgical site infections and extended hospital stay: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2021, 49, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide. 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/80135/9789241501507_eng.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Karaaslan, A.; Kepenekli Kadayifci, E.; Atıcı, S.; Sili, U.; Soysal, A.; Çulha, G.; Pekru, Y.; Bakır, M. Compliance of Healthcare Workers with Hand Hygiene Practices in Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive Care Units: Overt Observation. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2014, 2014, 306478. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ipid/2014/306478/ (accessed on 3 April 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoukian, S.; Stewart, S.; Dancer, S.; Graves, N.; Mason, H.; McFarland, A.; Robertson, C.; Reilly, J. Estimating excess length of stay due to healthcare-associated infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis of statistical methodology. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 100, 222–235. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670118303177 (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Robertson, C.; Pan, J.; Kennedy, S.; Haahr, L.; Manoukian, S.; Mason, H.; Kavanagh, K.; Graves, N.; Dancer, S.; et al. Impact of healthcare-associated infection on length of stay. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 114, 23–31. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670121001882 (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- WHO. Fact Sheet. Occupational Health: Health Workers. 7 November 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/occupational-health--health-workers (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Allegranzi, B.; Nejad, S.B.; Combescure, C.; Graafmans, W.; Attar, H.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. The burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 228–241. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)61458-4/fulltext (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.; Brewster, L.; Tarrant, C. Making infection prevention and control everyone’s business? Hospital staff views on patient involvement. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, A.; Genovese-Schek, V.; Agarwal, M.; Wurmser, T.; Larson, E. Relationship between patient safety climate and adherence to standard precautions. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016, 44, 1128–1132. Available online: http://www.ajicjournal.org/article/S0196-6553(16)30421-7/references (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Duodu, P.A.; Darkwah, E.; Agbadi, P.; Duah, H.O.; Nutor, J.J. Prevalence and geo-clinicodemographic factors associated with hepatitis B vaccination among healthcare workers in five developing countries. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Healthcare-Associated Infections. Fact Sheet.. Available online: http://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/gpsc_ccisc_fact_sheet_en.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- WHO. The Burden of Healthcare-Associated Infection Worldwide [Internet]. Who.int. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/burden_hcai/en/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Shajahan, S.; Shaji, S.C.; Francis, S.; Najad, M.; Vasanth, I.; Aranha, P.R. Knowledge and Practice Regarding Universal Precautions among Health Care Workers at a Selected Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2023, 14, 2350–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cdc.gov. Standard Precautions for All Patient Care Basics Infection Control CDC. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- CDC. Standard Precautions for All Patient Care. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/summary-infection-prevention-practices/standard-precautions.html (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- WHO. Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care is Safer Care. 2009. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44102/9789241597906_eng.pdf;jsessionid=8BF76AB89C8480E9ABCF42FD84A63D38?sequence=1 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, M.A.; Lee, M.H.; Park, Y.J. Perception of infection control education and practices among nursing students in Korea: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.S.; Corrêa, I.; Salgado, M.E. Knowledge of nursing undergraduate students about the use of contact precautions measures. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2014, 32, 464–472. Available online: https://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/iee/article/view/17507/15729 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Joshi, S.C.; Diwan, V.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Joshi, R.; Shah, H.; Sharma, M.; Pathak, A.; Macaden, R.; Lundborg, C.S. Staff Perception on Biomedical or Health Care Waste Management: A Qualitative Study in a Rural Tertiary Care Hospital in India. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128383. Available online: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0128383 (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Dhedhi, N.A.; Ashraf, H.; Jiwani, A. Knowledge of standard precautions among healthcare professionals at a Teaching Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarko, S.; Azazh, A.; Abebe, Y. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice of fourth, fifth- and sixth-year medical students on standard precautions in Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2014. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2015, 1, 34–40. Available online: https://www.rroij.com/open-access/assessment-of-the-knowledge-attitude-and-practice-of-fourthfifth-and-sixth-year-medical-students-on-standard-precaution-intikur-anbessa-specialized-hospital-addis-ababa-ethiopia-2014.php?aid=60746 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Medical Council of India. List of Colleges Teaching MBBS. Available online: https://www.mciindia.org/CMS/information-desk/for-students-to-study-in-india/list-of-college-teaching-mbbs (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, R.; Shah, H.; Macaden, R.; Lundborg, C. A step-wise approach towards introduction of an alcohol based hand rub, and implementation of front line ownership- using a, rural, tertiary care hospital in central India as a model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 182. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-015-0840-1 (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response, Standard Precautions in Health Care. October 2007. Available online: https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/EPR_AM2_E7.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- ICMR. Hospital Infection Control Guidelines, New Delhi, India 2017. Available online: https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/Hospital_Infection_control_guidelines.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Liu, X.; Long, Y.; Greenhalgh, C.; Steeg, S.; Wilkinson, I.; Li, H.; Verma, A.; Spencer, V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors associated with healthcare-associated infections among hospitalized patients in Chinese general hospitals from 2001 to 2022. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 135, 37e49. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36907333/ (accessed on 3 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cheesbrough, J.S.; Levy, J.; Lahuerta-Marin, A. Infection prevention and control teaching in undergraduate healthcare curricula: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, N.; Chungong, S.; O’Hearn, K. Teaching infection prevention and control to medical students: A scoping review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 102, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudedla, S.; Reddy, K.; Sowribala, M.; Tej, W. A study on knowledge and awareness of standard precautions among health care workers at Nizam′s institute of medical sciences Hyderabad. J. Natl. Accredit. Board Hosp. Healthc. Provid. 2014, 1, 34. Available online: http://www.nabh.ind.in/article.asp?issn=23191880;year=2014;volume=1;issue=2;spage=34;epage=38;aulast=Mudedla (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Amin, T.; Al Noaim, K.; Bu Saad, M.; Al Malhm, T.; Al Mulhim, A.; Al Awas, M. Standard Precautions and Infection Control, Medical Students’ Knowledge and Behavior at a Saudi University: The Need for Change. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Sharma Sarkar, B.; Goswami, D.; Ghosh, S.; Samanta, A. Knowledge and Practice of Standard Precautions and Awareness Regarding Post-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV among Interns of a Medical College in West Bengal, India. Oman Med. J. 2013, 28, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakob, E.; Lamaro, T.; Henok, A. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Infection Control Measures among Mizan-Aman General Hospital Workers, South West Ethiopia. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2015, 5, 1000370. Available online: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/knowledge-attitude-and-practice-towards-infection-control-measures-among-mizanaman-general-hospital-workers-south-west-ethiopia-2161-0711-1000370.php?aid=61015 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Rodrigues, P.S.; de Sousa, A.F.L.; Magro, M.C.D.S.; de Andrade, D.; Hermann, P.R.D.S. Occupational accidents among nursing professionals working in critical units of an emergency service. Esc. Anna Nery 2017, 21, e20170040. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/ean/a/8Y7gtRJmSF7NsbM96dGv3QB/?lang=en&format=html (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Patan, S.; Shobhawat, A. Need of Biomedical Waste Management System in Hospitals—An Emerging issue—A Review. Curr. World Environ. 2012, 7, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, B.; Patnaik, S.; Patnaik, N. Impact of Improper Biomedical Waste Disposal on Human Health and Environment during COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2021, 8, 4137–4143. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, Y.; Agarwal, A.; Bouvet, F. Safe Management of Wastes from Health-Care Activities, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 978 92 4 154856. [Google Scholar]

- National Aids Control Organisation. Available online: http://naco.gov.in/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- National Aids Control Organisation, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. National Guidelines of HIV Testing. July 2015. Available online: http://www.naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/National_Guidelines_for_HIV_Testing_21Apr2016.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Aminde, L.N.; Takah, N.F.; Noubiap, J.J.N.; Tindong, M.; Ngwasiri, C.; Jingi, A.M.; Kengne, A.P.; Dzudie, A. Awareness and low uptake of post exposure prophylaxis for HIV among clinical medical students in a high endemicity setting. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Questions with Correct Answers | Total N = 600; n (%) | MBBS N = 423; n (%) | Nursing N = 177; n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Select the correct definition of standard precautions (select correct definition) 1 | 250 (48) | 209 (49) | 41 (23) | <0.05 |

| 2. | Select the correct statements | ||||

| (a) Washed gloves cannot be reused. (Correct) | 336 (56) | 258 (61) | 78 (44) | <0.05 | |

| (b) Cotton or gauze masks are not advantageous over surgical masks. (Correct) | 290 (48) | 225 (53) | 65 (37) | <0.05 | |

| (c) All types of body fluids of a patient are considered infectious. (Correct) | 269 (45) | 166 (39) | 103 (58) | <0.05 | |

| (d) All patients must be considered as potential sources of infection. (Correct) | 203 (34) | 115 (27) | 88 (50) | <0.05 | |

| 3. | Select the correct option based on the WHO hand-hygiene recommendations | 126 (21) | 111 (26) | 15 (9) | <0.05 |

| (a) There are five moments of HH based on “my 5 moments for hand hygiene”. | 86 (14) | 84 (20) | 2 (1) | <0.05 | |

| (b) There are six steps to complete HH with ABHR. | 171 (29) | 163 (39) | 8 (5) | <0.05 | |

| (c) There are eight steps in the standard handwashing technique. | 70 (12) | 52 (12) | 18 (10) | >0.05 | |

| (d) The time required for washing hands with soap and water is 40–60 s. | 166 (28) | 142 (34) | 24 (14) | <0.05 | |

| (e) The time required for hand rub using an ABHR is 20–30 s. | 139 (23) | 115 (27) | 24 (14) | <0.05 | |

| 4. | Correct knowledge of when to perform hand hygiene | 481 (80) | 334 (79) | 147 (83) | |

| (a) It is necessary to wash hands with soap and water | 478 (80) | 327 (77) | 151 (85) | <0.05 | |

| (i) Before wearing gloves. | 424 (71) | 275 (65) | 149 (84) | >0.05 | |

| (ii) After removing gloves. | 555 (93) | 390 (92) | 165 (93) | >0.05 | |

| (iii) After contact with inanimate objects near a patient. | 553 (92) | 387 (91) | 166 (94) | >0.05 | |

| (iv) After touching body fluids, or contaminated items, even if gloves were worn | 513 (86) | 365 (86) | 148 (84) | >0.05 | |

| (v) Before handling invasive devices. | 486 (81) | 342 (81) | 144 (81) | >0.05 | |

| (vi) After a general examination of an anemic patient. | 343 (57) | 208 (49) | 135 (76) | <0.05 | |

| (b) Gloves should be changed while dressing two sites on the same patient. | 431 (72) | 321 (76) | 110 (62) | >0.05 | |

| (c) Hand ornaments should be removed at the workplace. | 550 (92) | 387 (91) | 163 (92) | <0.05 | |

| 5. | The full form of PEP is “post-exposure prophylaxis”. | 174 (29) | 155 (37) | 19 (11) | <0.05 |

| 6. | PEP is performed after exposure to infectious material but before onset of the disease. | 178 (30) | 147 (35) | 31 (18) | <0.05 |

| 7. | Antiretroviral drugs are the only effective medicines for PEP. | 181 (30) | 128 (30) | 53 (30) | >0.05 |

| 8. | An N95 respirator is the best PPE to protect against infection by airborne diseases. | 127 (21) | 102 (24) | 25 (14) | <0.05 |

| 9. | Biomedical waste is segregated at the study hospital. | 290 (48) | 170 (40) | 120 (68) | <0.05 |

| 10. | The correct color of the bins used to dispose of biomedical wastes | ||||

| (a) Infectious wastes: bandages, gauze, and cotton swabs are disposed of in the yellow bin. | 123 (21) | 63 (15) | 60 (34) | <0.05 | |

| (b) The patient’s body fluids and wastes are disposed of in the yellow bin. | 103 (17) | 38 (9) | 65 (37) | <0.05 | |

| (c) All types of glass (bottles and broken glass articles) are disposed of in the blue bin. | 102 (17) | 62 (15) | 40 (23) | >0.05 | |

| (d) Needles, syringes, razor blades, and metal articles are disposed of in the black bin. | 43 (7) | 30 (6) | 13 (7) | >0.05 | |

| (e) Plastic catheters, syringes, and intravenous fluid packages are disposed of in the red bin. | 82 (14) | 45 (11) | 37 (21) | <0.05 | |

| (f) Expired medicines are disposed of in the blue bin. | 16 (3) | 9 (2) | 7 (4) | >0.05 | |

| (g) Used PPE cannot be discarded by regular municipal disposal systems. | 183 (31) | 144 (34) | 39 (22) | <0.05 | |

| 11. | Decode the hazard symbols | ||||

(a)  (Biohazard) (Biohazard) | 76 (13) | 74 (17) | 2 (1) | <0.05 | |

(b)  (Radioactive material) (Radioactive material) | 60 (10) | 60 (14) | 0 (0) | <0.05 | |

(c)  (Explosive) (Explosive) | 56 (9) | 56 (13) | 0 (0) | <0.05 | |

(d)  (Inflammable) (Inflammable) | 231 (39) | 179 (42) | 52 (29) | <0.05 | |

(e)  (Nonionizing radiation) (Nonionizing radiation) | 95 (16) | 93 (22) | 2 (1) | <0.05 |

| Expected Correct Responses to the Questions | Total n (%) | MBBS n (%) | Nursing n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude and Beliefs | N = 600 | N = 423 | N = 177 | ||

| 1. | (a) Previously attended HH training and would also like to attend training in future. | 188 (31) | 169 (40) | 19 (11) | <0.05 |

| (b) Did not previously attend any training but would like to attend in future. | 265 (44) | 169 (40) | 96 (54) | <0.05 | |

| 2. | A used needle should be disposed of by separating the needle with a needle cutter. | 165 (28) | 55 (13) | 110 (62) | <0.05 |

| 3. | An episode of needle stick injury should be notified to the ART center. | 116 (19) | 91 (22) | 25 (14) | >0.05 |

| 4. | (a) ABHR does not replace the need for handwashing in any condition. | 243 (41) | 195 (46) | 48 (27) | <0.05 |

| (b) Use of gloves does not replace the need for HH. | 349 (58) | 320 (76) | 102 (58) | >0.05 | |

| (c) Used needles should not be recapped before disposal. | 349 (58) | 320 (76) | 29 (16) | <0.05 | |

| (d) Used needles must be bent with a needle cutter after use. | 488 (81) | 343 (81) | 145 (82) | >0.05 | |

| (e) Soiled sharp objects must be shredded before final disposal. | 453 (76) | 325 (77) | 128 (72) | >0.05 | |

| (g) Family members/nursing staff can remind the doctor to perform hand hygiene. | 451 (75) | 312 (74) | 139 (79) | >0.05 | |

| 5. | HCPs are at high risk while treating patients and during their clinical postings | 147 (25) | 87 (21) | 60 (34) | <0.05 |

| 6. | List the infections that can be caused due to needle stick injury (HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C). | 365 (61) | 279 (66) | 86 (49) | <0.05 |

| 7. | The present study has sensitized me to the importance of SPs. | 351 (59) | 281 (66) | 70 (40) | <0.05 |

| 8. | I am not convinced that SPs are necessary. | 111 (19) | 45 (11) | 66 (37) | <0.05 |

| Practice (correct practice) | Total n (%) | MBBS n (%) | Nursing n (%) | p-value | |

| N = 600 | N = 423 | N = 177 | |||

| 9. | List the instruments you use as standard precautions during clinical practice | ||||

| (a) Apron | 38 (6) | 3 (2) | 35 (8) | <0.05 | |

| (b) Mask | 71 (12) | 22 (12) | 49 (12) | <0.05 | |

| (c) Handwashing/ABHR | 153 (26) | 32 (18) | 121 (29) | <0.05 | |

| (d) Sterilization of instruments | 35 (6) | 3 (2) | 32 (8) | <0.05 | |

| (e) Proper management of BMW | 27 (5) | 0 (0) | 27 (27) | <0.05 | |

| (f) Gloves | 171 (29) | 23 (13) | 148 (35) | <0.05 | |

| 10. | If during a lumbar puncture: accidental spilt of the cerebrospinal fluid should be promptly wiped off and the surface should be cleaned using a disinfectant, followed by proper handwashing with soap and water. | 430 (72) | 300 (71) | 130 (73) | >0.05 |

| 11. | If a patient with pulmonary infection starts coughing and spits toward you during the examination: advice should be sought from a pulmonary consultant. | 357 (60) | 237 (56) | 120 (68) | >0.05 |

| 12. | If a patient is about to vomit: the HCP should wear gloves and a mask and bring the kidney tray to help the patient. | 476 (79) | 329 (78) | 147 (83) | >0.05 |

| 13. | To manage a patient with severe bleeding in an emergency department, immediate attempts should be made to prevent bleeding from the injured site by having gloves on. | 221 (37) | 127 (30) | 94 (53) | <0.05 |

| 14. | To collect blood samples: HCPs should wash and dry hands, wear gloves and a face mask, sterilize the site, and withdraw the blood. | 361 (60) | 204 (48) | 157 (89) | <0.05 |

| 15. | In a code blue emergency at a cardiac intensive care unit: CPR should be performed only after using the available PPE. | 184 (31) | 101 (24) | 83 (47) | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, M.; Bachani, R. Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Perceived Barriers for the Compliance of Standard Precautions among Medical and Nursing Students in Central India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085487

Sharma M, Bachani R. Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Perceived Barriers for the Compliance of Standard Precautions among Medical and Nursing Students in Central India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(8):5487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085487

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Megha, and Rishika Bachani. 2023. "Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Perceived Barriers for the Compliance of Standard Precautions among Medical and Nursing Students in Central India" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 8: 5487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085487

APA StyleSharma, M., & Bachani, R. (2023). Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Perceived Barriers for the Compliance of Standard Precautions among Medical and Nursing Students in Central India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(8), 5487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085487