Development of an Australian FASD Indigenous Framework: Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Australian FASD Narratives as A Barrier to Accessing Knowledge, Diagnosis and Support

1.2. Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Pathways

1.3. Australian Guide to the Diagnosis of FASD

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Knowledge Holders

2.2. The Authors

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Phase One: Mapping the Selected Data Sources

2.3.2. Phase Two: Extensive Reading and Categorising of the Selected Data

2.3.3. Phase Three: Identifying and Naming Concepts

2.3.4. Phase Four: Integrating the Concepts

2.3.5. Phase Five: Synthesis, Resynthesis and Making It All Make Sense

2.3.6. Phase Six: Validating the Conceptual Framework

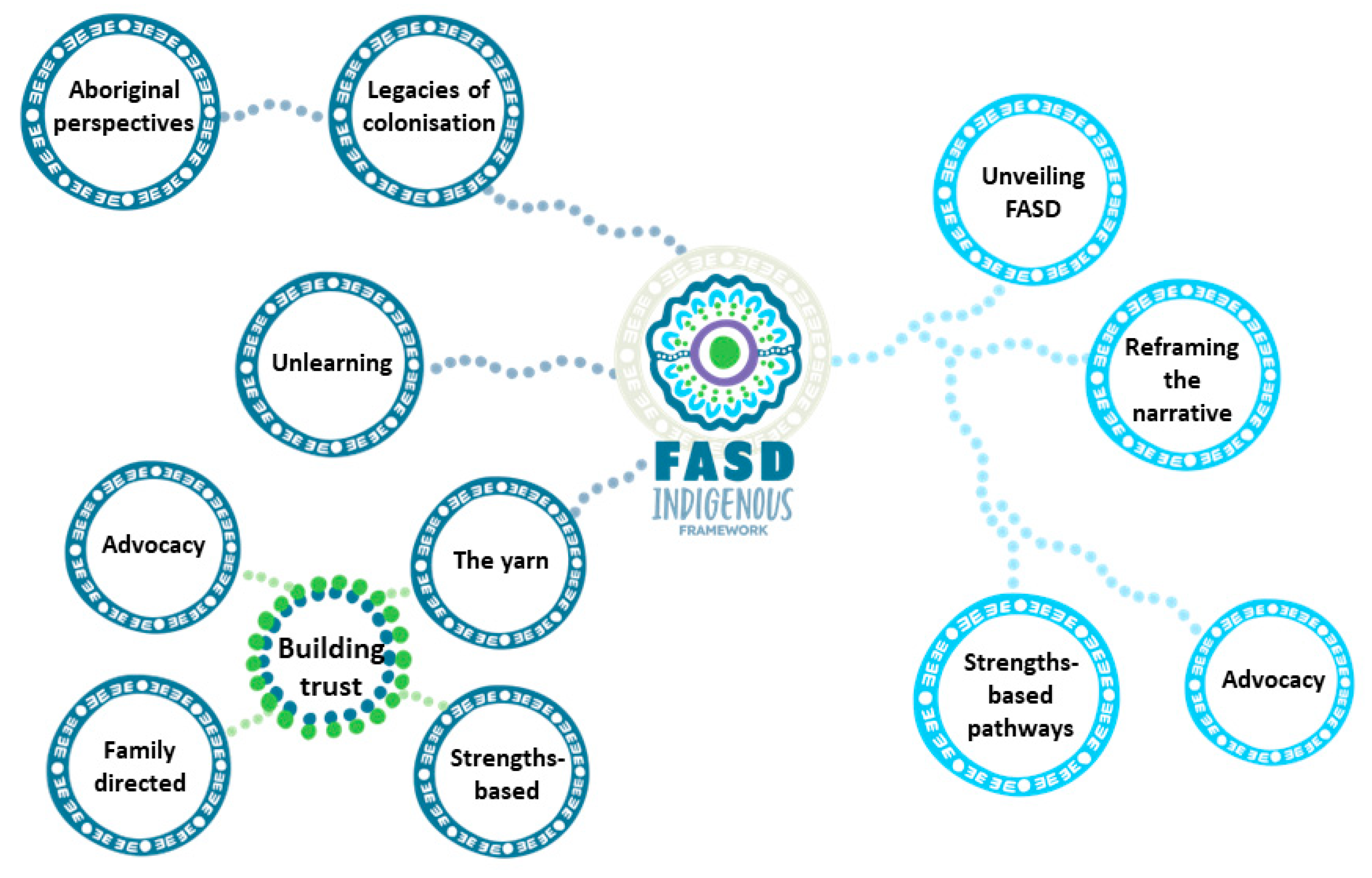

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Collaborative Group and Two-Way Individual Yarns

3.3. Conceptual Model

3.4. What Clinicians Need to Know, Be and Do

3.4.1. What Clinicians Need to Know

- Legacies of Colonisation

“The impairments that these kids had were not necessarily solely related to FASD. You know, they have backgrounds of significant trauma and that might also be a significant contributing factor for why they might be impulsive, or why they can’t sit still or focus. You can’t diagnose FASD and wrap it all up in a nice shiny package with a ribbon on top. Untreated trauma is a significant issue that has major implications for a child’s neurodevelopment”.

“If we are to work effectively and appropriately with Māori, we need to understand the full context of Aotearoa’s history. We need to be aware of the systemic and institutional racism around us and within us. And what the impacts of this are for our clients and for our own roles, values, and beliefs as clinicians”.

- Aboriginal perspectives

“On this journey, Aboriginal people need strong allies who become informed, and uphold Aboriginal worldviews and frameworks in the translation into clinical approaches and practice”.

3.4.2. What Clinicians Need to Be

- Unlearning

“Forget the questions because you will never get the answers or an honest account of what’s going on—these kids will tell you what they think you want to hear. Talk to them like you are talking to your own kids”.

“We should assess kids by how well they do the things they are used to. So, thinking about assessing fine motor skills using handwriting, or with a pencil and paper. In some cases, kids that were being assessed came from very, very remote communities, where using a pencil and paper would have been very foreign to them. If their fine motor skills were assessed by, say, tying a fishing line, it could have been a very different outcome”.

“Non-Indigenous clinicians must do much more than simply learn about the Indigenous cultures that they work with. It is essential they look within and identify their own cognitive biases from their life experiences and their clinical frameworks, and work to consistently unlearn and retrain responses stemming from these”.

3.4.3. What Clinicians Need to Do

- The yarn

“So I’ll say “oh I’m from [hometown] and I’ve got a little sister and a big brother, I don’t live with mum and dad anymore because I’m old”. They get to know you and they think “okay she is sharing so that makes me feel more comfortable to share”. They know something about me and the kids begin to find the similarities and points of connection—they can relate to you”.

“How can trust someone I don’t know? If a doctor, clinician—anyone really—doesn’t understand the power of my story and the importance of listening to who I am, how can they possibly offer worthy knowledge to advise to me?”

“I’ve learnt over time, that you have to step back and go, you know what? This kid just wants to tell me about the YouTube video he watched last night and that’s fine. And if that’s what we get through today then hey, he’s leaving happy”.

- Family-directed yarn

- Applying a strengths-based wellbeing approach

- Advocacy

“For Aboriginal peoples, the escalation to child removal and justice is significantly sharper than for non-Aboriginal peoples”.

3.5. What Aboriginal Communities Need to Know, Be and Do

3.5.1. What Aboriginal Communities Need to Know

- Unveiling FASD

“The silent story of FASD within all our families has been there for many years, waiting to be recognised and understood by society. Family narratives of FASD must be told to bring forward hope, reforms and a new era of awareness to replace what is too often described as “despair and hopelessness” by families caring for children adolescents with FASD”.[7] (p. 1).

“The ritual of being intoxicated due to the consumption of alcohol is not the custom of Aboriginal people. It has nothing to do with Aboriginal culture and everything to do with the hopelessness of being immersed in cycles of intergenerational boredom, learned behaviours, power struggles, crisis, vulnerability, abuse, trauma, poverty, grief and loss. We have children that wake up and drink their parents’ alcohol because they are hungry and need something to fill their bellies. Their parents did the same and their parents before that. Here, cycles of loneliness and being alone begin and our children become desperate for connection. This desperation creates gangs of lonely, hungry, isolated, traumatised children with FASD that have been starved of love and all the other basic needs. The only thing these kids are focused on is survival and that leads to a life of crime. That is not a choice, there is no freedom or self-determination in these situations”.

3.5.2. What Aboriginal Communities Need to Be

- Reframing the narrative

“We need to take back our narratives. We lead the way in FASD research and knowledge translation, not because FASD in an “Aboriginal problem” but rather because our cultural ways are powerful, strengths-based and holistic. When the narrative lacks our Aboriginal voice and ownership, deficit discourses that focus on Aboriginal shame and blame emerge and this plays out at a grass roots level for our people. We are sovereign people and these narratives belong to us”.

3.5.3. What Aboriginal Communities Need to Do

- Strengths-based pathways

- Advocacy

“We don’t want our kids knowing the language of the court and these systems. We want our kids knowing their languages, and the language of community and strength”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Yarning in Practice

“They don’t get to be an expert in the classroom and because they don’t have those social skills, they don’t get to be the experts in the playground…so for them to feel like an expert, that’s pretty tight…”

4.2. Yarning to Support Collaboration with Families

4.3. Supporting Aboriginal Communities to Access FASD Knowledges

4.4. Healing-Informed Approach to Gently “Unveil” FASD

“There was a lady who was very silent in the room, I sensed the rawness of her pain, I stopped the FASD training, and I encouraged everyone to get a cuppa. I went over to that lady. She hung her head, and I hung my mine, and we didn’t say much”.

“It’s not about being able to play didgeridoo or paint yourself up, you need to have the cultural and knowledge authority in FASD. You need to know how a community understands knowledge—how someone communicates, interprets, and constructs this thing called “knowledge”. What does that mean to the mob? How do they construct it in their mind and body? This is going to be different for every family because each family and even those that make up that family have their own ways of knowing, being and doing. We must never forget that”.

4.5. Intuitively and Practically Applying Humour

4.6. The Powerful Strength of Sovereign Aboriginal Peoples

“I would be saying jump up and down as loud as you can for the child…stay strong in your instincts, trust yourself, and ask for help, and especially with medical professionals, if at first you don’t have success try a different doctor; don’t stay with a doctor if you are not happy. Find someone who is actually going to help you and your child”.

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parter, C.; Wilson, S. My Research Is My Story: A Methodological Framework of Inquiry Told Through Storytelling by a Doctor of Philosophy Student. Qual. Inq. 2021, 27, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, G.; Anderson, K.; Gall, A.; Butler, T.L.; Whop, L.J.; Arley, B.; Cunningham, J.; Dickson, M.; Cass, A.; Ratcliffe, J.; et al. The Fabric of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing: A Conceptual Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hine, R.; Krakouer, J.; Elston, J.; Fredericks, B.; Hunter, S.-A.; Taylor, K.; Stephens, T.; Couzens, V.; Manahan, E.; DeSouza, R.; et al. Identifying and Dismantling Racism in Australian Perinatal Settings: Reframing the Narrative from a Risk Lens to Intentionally Prioritise Connectedness and Strengths in Providing Care to First Nations Families. Women Birth 2023, 36, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskie-Mendoza, S.; Tinajero, L.; Cervantes, A.; Rodriguez, J.; Serrata, J.V. Conducting Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) Through a Healing-Informed Approach with System-Involved Latinas. J. Fam. Violence 2018, 33, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S. Yarning, Hearing, Understanding, Knowing: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Assessment and Diagnosis for Justice-Involved Youth and Their Care Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, P.; Williamson, B.; Gibbs, L. Indigenous-Informed Disaster Recovery: Addressing Collective Trauma Using a Healing Framework. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2022, 16, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.D. Understanding Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) through the Stories of Nyoongar Families and How Can This Inform Policy and Service Delivery. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, L. An Aboriginal Woman’s Historical and Philosophical Enquiry to Identify the Outcomes of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Early Life Trauma in Indigenous Children Who Live in Aboriginal Communities in Queensland. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, K.L.; Jacob, M.M.; Mercier, A.; Heater, H.; Nall Goes Behind, L.; Joseph, J.; Kuerschner, S. An Indigenous Framework of the Cycle of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Risk and Prevention across the Generations: Historical Trauma, Harm and Healing. Ethn. Health 2021, 26, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is FASD?|About Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder|NOFASD Australia. Available online: https://www.nofasd.org.au/alcohol-and-pregnancy/what-is-fasd/ (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Skorka, K.; McBryde, C.; Copley, J.; Meredith, P.J.; Reid, N. Experiences of Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Their Families: A Critical Review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 44, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodituwakku, P.; Kodituwakku, E. Cognitive and Behavioral Profiles of Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2014, 1, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, C.L.M.; Kautz-Turnbull, C. From Surviving to Thriving: A New Conceptual Model to Advance Interventions to Support People with FASD across the Lifespan. In International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 61, pp. 39–75. ISBN 978-0-12-824585-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, L.; D’Antoine, H.; Carter, M. Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Aboriginal Communities. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice; Commonwealth Government of Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2014; ISBN 978-1-74241-090-6. [Google Scholar]

- Flannigan, K.; Wrath, A.; Ritter, C.; McLachlan, K.; Harding, K.D.; Campbell, A.; Reid, D.; Pei, J. Balancing the Story of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A Narrative Review of the Literature on Strengths. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 2448–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguiagaray, I.; Scholz, B.; Giorgi, C. Sympathy, Shame, and Few Solutions: News Media Portrayals of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Midwifery 2016, 40, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.; Elliott, E.; D’Antoine, H.; O’Leary, C.; Mahony, A.; Haan, E.; Bower, C. Health Professionals’ Knowledge, Practice and Opinions about Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Alcohol Consumption in Pregnancy. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2005, 29, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, S. ‘Two Ways’: Bringing Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Knowledges Together. In Country, Native Title and Ecology; Weir, J.K., Ed.; ANU Press: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2012; ISBN 978-1-921862-55-7. [Google Scholar]

- McKendrick, J.; Brooks, R.; Thorpe, M.; Bennett, P. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Programs: A Literature Review; Healing Foundation: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, S.L.; Maslen, S.; Best, D.; Freeman, J.; O’Donnell, M.; Reibel, T.; Mutch, R.; Watkins, R. Putting ‘Justice’ in Recovery Capital: Yarning about Hopes and Futures with Young People in Detention. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr. 2020, 9, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kully-Martens, K.; McNeil, A.; Pei, J.; Rasmussen, C. Toward a Strengths-Based Cognitive Profile of Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Implications for Intervention. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2022, 9, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.L.; Maslen, S.; Watkins, R.; Conigrave, K.; Freeman, J.; O’Donnell, M.; Mutch, R.C.; Bower, C. ‘That Thing in His Head’: Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Australian Caregiver Responses to Neurodevelopmental Disability Diagnoses. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 42, 1581–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, N.; Akison, L.K.; Goldsbury, S.; Hewlett, N.; Elliott, E.J.; Finlay-Jones, A.; Shanley, D.C.; Bagley, K.; Crawford, A.; Till, H.; et al. Key Stakeholder Priorities for the Review and Update of the Australian Guide to Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, C.; Elliott, E.J.; Zimmet, M.; Doorey, J.; Wilkins, A.; Russell, V.; Shelton, D.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Watkins, R. Australian Guide to the Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A Summary: Brief Communication. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 53, 1021–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinsworth, D. Decolonizing Indigenous Disability in Australia. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrup-Stewart, C.; Whyman, T.; Jobson, L.; Adams, K. Understanding Culture: The Voices of Urban Aboriginal Young People. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 1308–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Mirraboopa, B. Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing: A Theoretical Framework and Methods for Indigenous and Indigenist Re-search. J. Aust. Stud. 2003, 27, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigney, L.-I. Internationalization of an Indigenous Anticolonial Cultural Critique of Research Methodologies: A Guide to Indigenist Research Methodology and Its Principles. Wicazo Sa Rev. 1999, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmil, H.; Kelly, J.; Bowden, M.; Galletly, C.; Cairney, I.; Wilson, C.; Hahn, L.; Liu, D.; Elliot, P.; Else, J.; et al. Participatory Action Research-Dadirri-Ganma, Using Yarning: Methodology Co-Design with Aboriginal Community Members. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungunmerr-Baumann, M.-R.; Groom, R.A.; Schuberg, E.L.; Atkinson, J.; Atkinson, C.; Wallace, R.; Morris, G. Dadirri: An Indigenous Place-Based Research Methodology. Altern. Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2022, 18, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terare, M.; Rawsthorne, M. Country Is Yarning to Me: Worldview, Health and Well-Being Amongst Australian First Nations People. Br. J. Soc. Work 2020, 50, 944–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geia, L.K.; Hayes, B.; Usher, K. Yarning/Aboriginal Storytelling: Towards an Understanding of an Indigenous Perspective and Its Implications for Research Practice. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 46, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredericks, B.; Adams, K.; Finlay, S.; Fletcher, G.; Andy, S.; Briggs, L.; Briggs, L.; Hall, R. Engaging the Practice of Indigenous Yarning in Action Research. ALAR Action Learn. Action Res. J. 2011, 17, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bessarab, D.; Ng’andu, B. Yarning About Yarning as a Legitimate Method in Indigenous Research. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 2010, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, T.; Bennett, B. Creating a Culturally Safe Space When Teaching Aboriginal Content in Social Work: A Scoping Review. Aust. Soc. Work 2019, 72, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, M. Extending the Yarning Yarn: Collaborative Yarning Methodology for Ethical Indigenist Education Research. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 2019, 50, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indigenous Allied Health Australia. Cultural Responsiveness in Action: An IAHA Framework; Indigenous Allied Health Australia: Deakin, ACT, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Telethon Kids Institute; Hamilton, S.; Doyle, M.; University of Sydney; Bower, C. Telethon Kids Institute Review of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. J. Aust. Indig. Health 2021, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabareen, Y. Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definitions, and Procedure. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.; Ruston, S.; Irwin, S.; Tran, P.; Hotton, P.; Thorne, S. Taking Culture Seriously: Can We Improve the Developmental Health and Well-Being of Australian Aboriginal Children in out-of-Home Care? Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagg, H.; Tulich, T.; Bush, Z. Indefinite Detention Meets Colonial Dispossession: Indigenous Youths With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in a White Settler Justice System. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2017, 26, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Reibel, T.; Maslen, S.; Watkins, R.; Jacinta, F.; Passmore, H.; Mutch, R.; O’Donnell, M.; Braithwaite, V.; Bower, C. Disability “In-Justice”: The Benefits and Challenges of “Yarning” With Young People Undergoing Diagnostic Assessment for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in a Youth Detention Center. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.L.; Reibel, T.; Watkins, R.; Mutch, R.C.; Kippin, N.R.; Freeman, J.; Passmore, H.M.; Safe, B.; O’Donnell, M.; Bower, C. ‘He Has Problems; He Is Not the Problem’ A Qualitative Study of Non-Custodial Staff Providing Services for Young Offenders Assessed for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in an Australian Youth Detention Centre. Youth Justice 2019, 19, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammill, J. Granny Rights: Combatting the Granny Burnout Syndrome among Australian Indigenous Communities. Development 2001, 44, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, N.; Crawford, A.; Petrenko, C.; Kable, J.; Olson, H.C. A Family-Directed Approach for Supporting Individuals with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2022, 9, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, N.; Page, M.; McDonald, T.; Hawkins, E.; Liu, W.; Webster, H.; White, C.; Shelton, D.; Katsikitis, M.; Wood, A.; et al. Integrating Cultural Considerations and Developmental Screening into an Australian First Nations Child Health Check. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2022, 28, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, N.; Hawkins, E.; Liu, W.; Page, M.; Webster, H.; Katsikitis, M.; Shelton, D.; Wood, A.; O’Callaghan, F.; Morrissey, S.; et al. Yarning about Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Outcomes of a Community-Based Workshop. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 108, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, M.; Enns, J.E.; Hanlon-Dearman, A.; Chateau, D.; Phillips-Beck, W.; Singal, D.; MacWilliam, L.; Longstaffe, S.; Chudley, A.; Elias, B.; et al. Health, Social, Education, and Justice Outcomes of Manitoba First Nations Children Diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A Population-Based Cohort Study of Linked Administrative Data. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.; Jacobson, K. Cross-Cultural Considerations in Pediatric Neuropsychology: A Review and Call to Attention. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2015, 4, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.J.; McLachlan, K.; Roesch, R. Resilience and Enculturation: Strengths among Young Offenders with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2020, 8, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L.G. Aboriginal Women, Alcohol and the Road to Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 197, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, B.J. An Evaluation of a Program Supporting Indigenous Youth Through Their FASD Assessment. Ph.D. Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Paradies, Y. Colonisation, Racism and Indigenous Health. J. Popul. Res. 2016, 33, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. Australian Human Rights Commission Social Justice Report 2011; Australian Human Rights Commission: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, K.; Reid, N.; Warner, J.; Shelton, D.; Dawe, S. A Qualitative Evaluation of Caregivers’ Experiences, Understanding and Outcomes Following Diagnosis of FASD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 63, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIHW Child Protection Australia 2019–20s20. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2019-20/summary (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Agency for Clinical Innovation Shared Decision Making. Available online: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/shared-decision-making (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Hammill, J.M. Culture of Chaos: Indigenous Women and Vulnerability in an Australian Rural Reserve. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Knowing and Being | Doing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belonging and Connection | Holistic Health | Purpose and Control | Dignity and Respect | Basic Needs | ||

| Culture | Reciprocal relationships with country, family and community and the importance of culture in developing and maintaining a sense of shared experience and understanding | Multidimensional state of wellness determined and attained via the quality and balance of one’s connections to family, community and culture | Stability at home, employment and financial security, education and cultural and familial responsibilities. Family was key to a sense of stability. | How perceived and treated by others and this is associated with relationships with others, policies, services, and experiences of racism. Family provides a source of shared strength that empowers and motivates. Additionally, having non-Aboriginal systems that value and respect culture being represented positively in media. | Housing, money, access to services, education, employment, opportunities to thrive and need for justice. | Actions and considerations required to deliver a culturally responsive assessment and diagnosis of FASD |

| Community | ||||||

| Family | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hewlett, N.; Hayes, L.; Williams, R.; Hamilton, S.; Holland, L.; Gall, A.; Doyle, M.; Goldsbury, S.; Boaden, N.; Reid, N. Development of an Australian FASD Indigenous Framework: Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065215

Hewlett N, Hayes L, Williams R, Hamilton S, Holland L, Gall A, Doyle M, Goldsbury S, Boaden N, Reid N. Development of an Australian FASD Indigenous Framework: Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):5215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065215

Chicago/Turabian StyleHewlett, Nicole, Lorian Hayes, Robyn Williams, Sharynne Hamilton, Lorelle Holland, Alana Gall, Michael Doyle, Sarah Goldsbury, Nirosha Boaden, and Natasha Reid. 2023. "Development of an Australian FASD Indigenous Framework: Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 5215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065215

APA StyleHewlett, N., Hayes, L., Williams, R., Hamilton, S., Holland, L., Gall, A., Doyle, M., Goldsbury, S., Boaden, N., & Reid, N. (2023). Development of an Australian FASD Indigenous Framework: Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065215