Nicotine Dependence among College Students Uninterested in Smoking Cessation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Survey Items

2.2.1. Items Related to Attributes and Smoking

2.2.2. KTSND

2.2.3. FTND

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

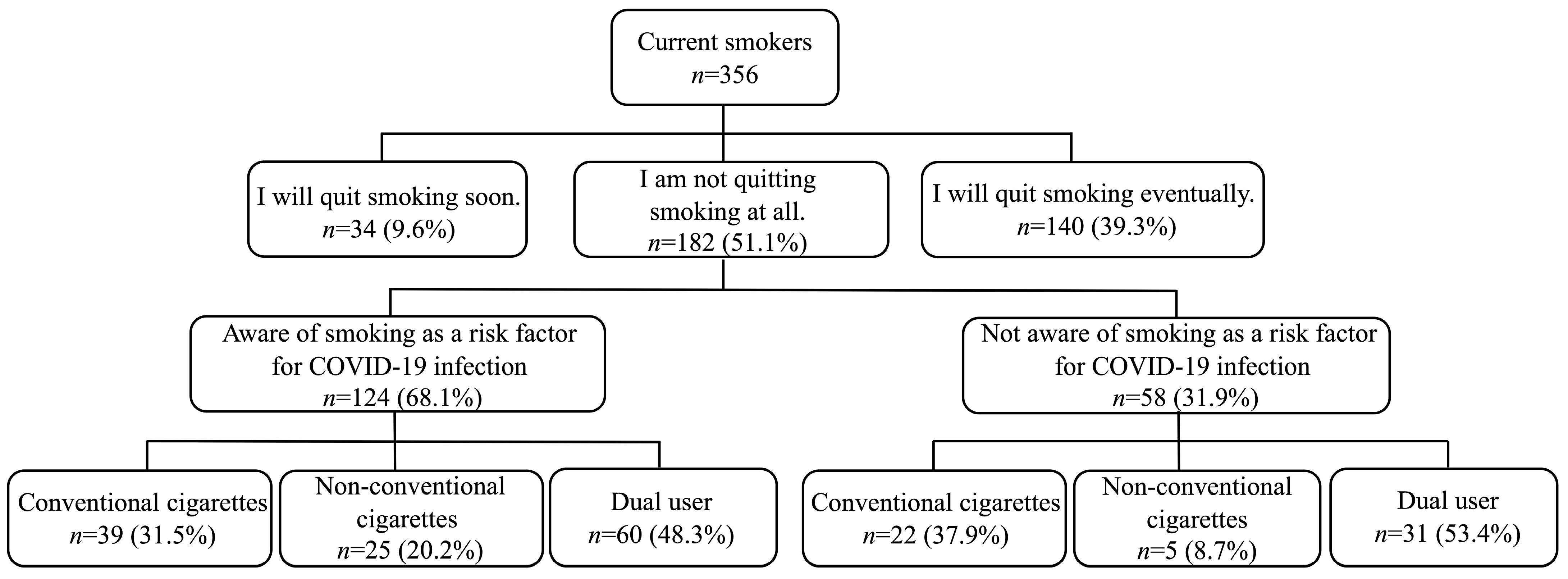

3.1. Basic Attributes

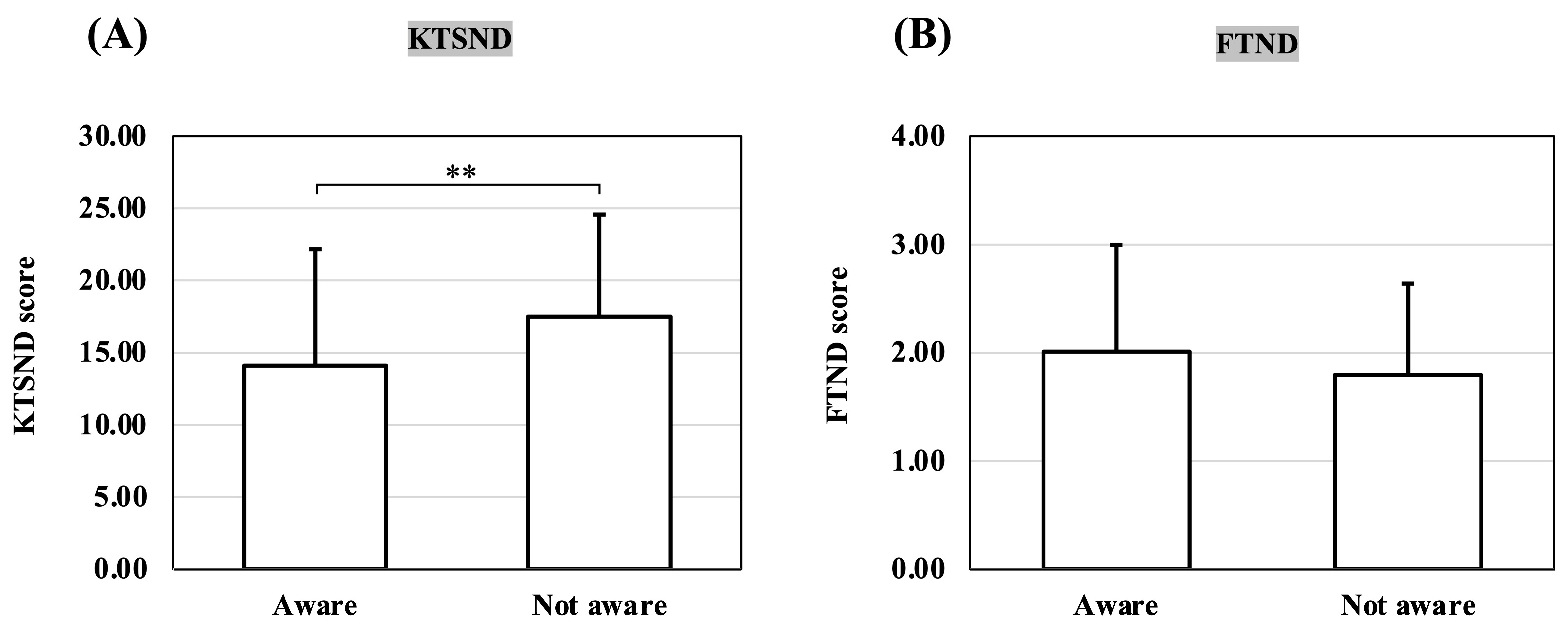

3.2. Comparison of KTSND and FTND by Awareness of Smoking as a Risk Factor for COVID-19

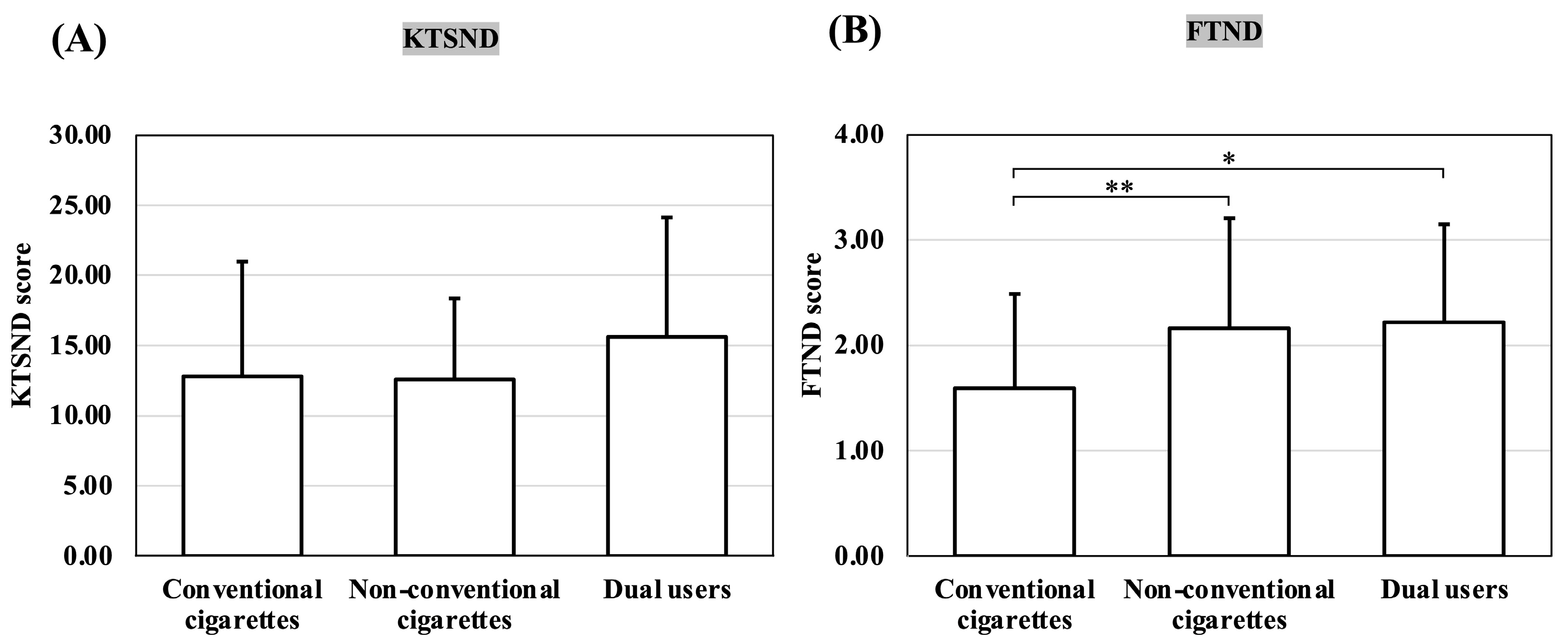

3.3. Comparison of KTSND and FTND Scores by Smoking Device among Those Aware That Smoking Is a Risk Factor for COVID-19

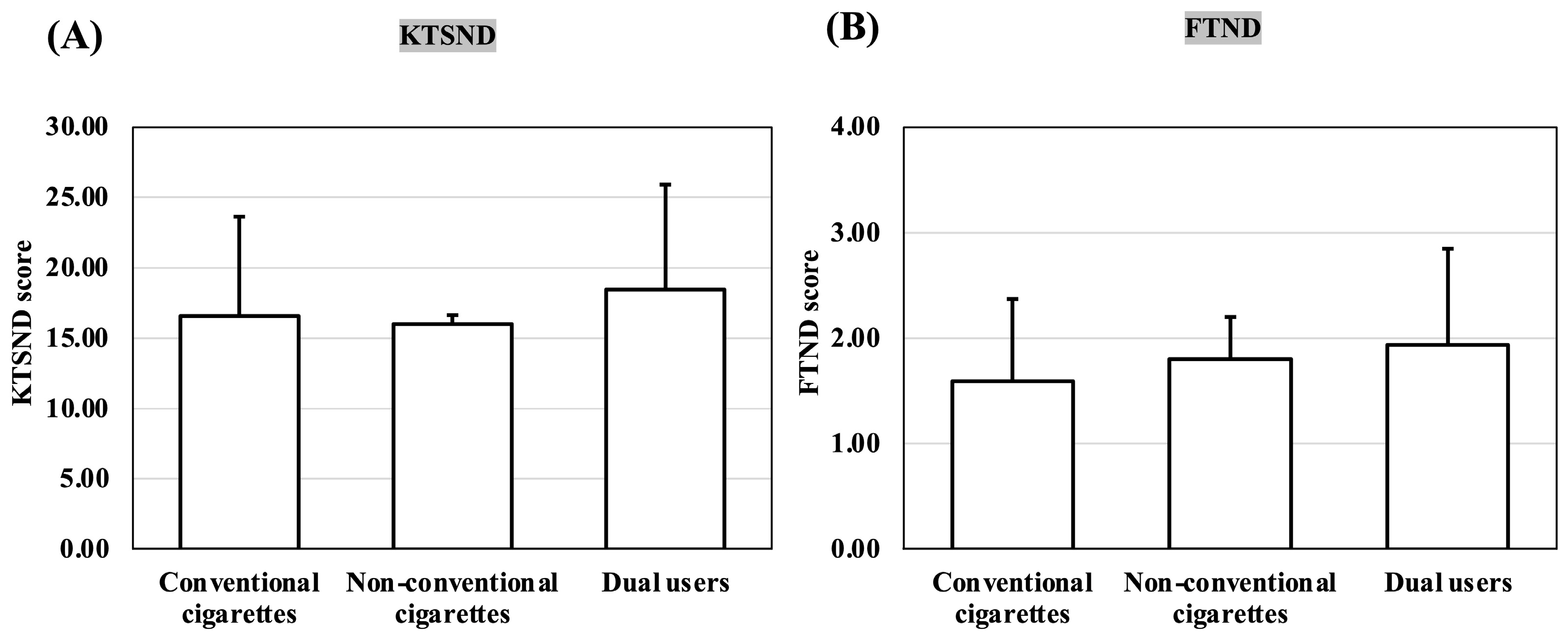

3.4. Comparison of KTSND and FTND Scores by Smoking Device among Those Unaware That Smoking Is a Risk Factor for COVID-19

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hackshaw, A.; Morris, J.K.; Boniface, S.; Tang, J.L.; Milenković, D. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: Meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ 2018, 360, j5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, E.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; Ito, H.; Matsuo, K.; Wakai, K.; Wada, K.; Nagata, C.; Tamakoshi, A.; Sugawara, Y.; et al. Smoking cessation and subsequent risk of cancer: A pooled analysis of eight population-based cohort studies in Japan. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017, 51, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, K.A.; Viscoli, C.M.; Spence, J.D.; Young, L.H.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Gorman, M.; Gerstenhaber, B.; Guarino, P.D.; Dixit, A.; Furie, K.L.; et al. Smoking cessation and outcome after ischemic stroke or TIA. Neurology 2017, 89, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K.S.M.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Pagano, I.; Williams, R.J.; Tam, E.K. E-cigarette use and respiratory disorder in an adult sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 194, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, R.; Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Wang, K.; Urman, R.; Hong, H.; Unger, J.; Samet, J.; Leventhal, A.; Berhane, K. Electronic cigarette use and respiratory symptoms in adolescents. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanavanich, R.; Glantz, S.A. Smoking is associated with COVID-19 progression: A meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goniewicz, M.L.; Knysak, J.; Gawron, M.; Kosmider, L.; Sobczak, A.; Kurek, J.; Prokopowicz, A.; Jablonska-Czapla, M.; Rosik-Dulewska, C.; Havel, C.; et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob. Control 2014, 23, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, M.; Brożek, G.M.; Lawson, J.; Skoczyński, S.; Majek, P.; Zejda, J.E. New ideas, old problems? Heated tobacco products—A systematic review. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2019, 32, 595–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdicke, F.; Picavet, P.; Baker, G.; Haziza, C.; Poux, V.; Lama, N.; Weitkunat, R. Effects of switching to the menthol tobacco heating system 2.2, smoking abstinence, or continued cigarette smoking on clinically relevant risk markers: A randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter study in sequential confinement and ambulatory settings (part 2). Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bekki, K.; Inaba, Y.; Uchiyama, S.; Kunugita, N. Comparison of chemicals in mainstream smoke in heat-not-burn tobacco and combustion cigarettes. J. UOEH 2017, 39, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auer, R.; Concha-Lozano, N.; Jacot-Sadowski, I.; Cornuz, J.; Berthet, A. Heat-not-burn tobacco cigarettes: Smoke by any other name. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1050–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Gentzke, A.S.; Apelberg, B.J.; Jamal, A.; King, B.A. Notes from the field: Use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1276–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, M.; Grogan, S.; Simms-Ellis, R.; Scholtens, K.; Sykes-Muskett, B.; Cowap, L.; Lawton, R.; Armitage, C.J.; Meads, D.; Schmitt, L.; et al. Patterns and predictors of e-cigarette, cigarette and dual use uptake in UK adolescents: Evidence from a 24-month prospective study. Addiction 2019, 114, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Tabuchi, T.; Miyashiro, I. E-cigarettes use behaviors in Japan: An online survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabuchi, T.; Gallus, S.; Shinozaki, T.; Nakaya, T.; Kunugita, N.; Colwell, B. Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: Its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol. Tob. Control 2018, 27, e25–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goniewicz, M.L.; Smith, D.M.; Edwards, K.C.; Blount, B.C.; Caldwell, K.L.; Feng, J.; Wang, L.; Christensen, C.; Ambrose, B.; Borek, N.; et al. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e185937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Ú.; Martínez-Loredo, V.; Simmons, V.N.; Meltzer, L.R.; Drobes, D.J.; Brandon, K.O.; Palmer, A.M.; Eissenberg, T.; Bullen, C.R.; Harrell, P.T.; et al. How does smoking and nicotine dependence change after onset of vaping? A retrospective analysis of dual users. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.P.; Schwamm, E.; Kalkhoran, S.; Noubary, F.; Walensky, R.P.; Rigotti, N.A. Respiratory symptom incidence among people using electronic cigarettes, combustible tobacco, or both. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, S.; Sata, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Iida, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Kato, S.; Hirata, A.; Kuwabara, K.; Shibuki, T.; Ishibashi, Y.; et al. Changes in smoking habits and behaviors following the introduction and spread of heated tobacco products in Japan and its effect on FEV(1) decline: A longitudinal cohort study. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinouani, S.; Pereira, E.; Tzourio, C. Electronic cigarette use in students and its relation with tobacco-smoking: A cross-sectional analysis of the i-share study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.; Nkemjika, S.; Yankey, B.; Okosun, I. Alternative tobacco product use and smoking quit attempts among teenagers in the United States: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2021, 13, e16740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallè, F.; Veshi, A.; Sabella, E.A.; Çitozi, M.; Da Molin, G.; Ferracuti, S.; Liguori, G.; Orsi, G.B.; Napoli, C. Awareness and behaviors regarding COVID-19 among Albanian undergraduates. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoike, M.; Mori, Y.; Hotta, K.; Shigeno, Y.; Aoyama, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Kouzai, H.; Kawamura, H.; Tsurudome, M.; Ito, M. Evaluation of Japanese university students’ perception of smoking, interest in quitting, and smoking behavior: An examination and public health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drug Discov. Ther. 2022, 16, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, F.G.N.; Demirel, G. Impact of a coronavirus pandemic on smoking behavior in university students: An online survey in Turkiye. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 19, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayran, G.; Kose, S.; Kucukoglu, S.; Aytekin Ozdemir, A. The effect of anxiety on nicotine dependence among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, C.; Kano, M.; Isomura, T.; Kunitomo, F.; Aizawa, M.; Harada, H.; Haradam, S.; Kawanami, Y.; Kido, M. Innovative questionnaire examining psychological nicotine dependence, “The Kano Test for Social Nicotine Dependence (KTSND)”. J. UOEH 2006, 28, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, T.; Yoshii, C.; Kano, M.; Kitada, M.; Inagaki, K.; Kurioka, N.; Isomura, T.; Hara, M.; Okubo, Y.; Koyama, H. Validity and reliability of Kano Test for Social Nicotine Dependence. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, M.; Musashi, M.; Kano, M. Reliability and validity of Kano Test for Social Nicotine Dependence (KTSND), and development of its revised scale assessing the psychosocial acceptability of smoking among university students. Hokkaido Igaku Zasshi 2011, 86, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström, K.O. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict. Behav. 1978, 3, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Frecker, R.C.; Fagerström, K.O. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991, 86, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.K.; Suman, L.N.; Srivastava, K.; Suma, N.; Vishwakarma, A. Psychometric properties of Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence: A systematic review. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2021, 30, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chertok, I.R.A. Perceived risk of infection and smoking behavior change during COVID-19 in Ohio. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.S. Factors associated with cigarette, e-cigarette, and dual use among South Korean adolescents. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.; Davis, K.C.; Cox, S.; Bradfield, B.; King, B.A.; Shafer, P.; Caraballo, R.; Bunnell, R. Reasons for current E-cigarette use among U.S. adults. Prev. Med. 2016, 93, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Nodate, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Tsuchiya, M.; Watanabe, M.; Niwa, S. Establishment of a practical training program in smoking cessation for use by pharmacists using cognitive-behavioral therapy and the motivational interview method. Yakugaku Zasshi 2012, 132, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrupatla, S.G.; Tavares, M.; Natto, Z.S. Tobacco use and effects of professional advice on smoking cessation among youth in India. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berlin, I. Therapeutic strategies to optimize the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapies. COPD 2009, 6, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edens, E.; Massa, A.; Petrakis, I. Novel pharmacological approaches to drug abuse treatment. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2010, 3, 343–386. [Google Scholar]

- West, R.J.; Jarvis, M.J.; Russell, M.A.; Carruthers, M.E.; Feyerabend, C. Effect of nicotine replacement on the cigarette withdrawal syndrome. Br. J. Addict. 1984, 79, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, K.; Lindson-Hawley, N.; Thomas, K.H.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lancaster, T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD006103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, J.W.; Brooks, P.R.; Vetelino, M.G.; Wirtz, M.C.; Arnold, E.P.; Huang, J.; Sands, S.B.; Davis, T.I.; Lebel, L.A.; Fox, C.B.; et al. Varenicline: An alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3474–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Pan, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, F.; Han, M.; Jia, C. The relationship between nicotine dependence and age among current smokers. Iran J. Public Health 2015, 44, 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, W.; Dierker, L.C.; Rose, J.S.; Selya, A.; Mermelstein, R.J. The natural course of nicotine dependence symptoms among adolescent smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 14, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.E.; Baker, T.B.; Benowitz, N.L.; Smith, S.S.; Jorenby, D.E. E-cigarette dependence measures in dual users: Reliability and relations with dependence criteria and e-cigarette cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etter, J.F.; Eissenberg, T. Dependence levels in users of electronic cigarettes, nicotine gums and tobacco cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 147, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.M.; Muilenburg, J.L.; Rathbun, S.L.; Yu, X.; Naeher, L.P.; Wang, J.S. Elevated nicotine dependence scores among electronic cigarette users at an electronic cigarette convention. J. Commun. Health 2018, 43, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzu-Hsuan Chen, D. The psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on changes in smoking behavior: Evidence from a nationwide survey in the UK. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2020, 6, 59. [Google Scholar]

| Questions | Choices and Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Smoking is a disease in itself. | DN(3) | PN(2) | PY(1) | DY(0) |

| 2: Smoking is a part of culture. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 3: Smoking is one of life’s pleasures. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 4: A smoking lifestyle should be respected. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 5: Some people’s lives are enriched by smoking. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 6: Smoking has physical or mental benefits. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 7: A cigarette is a stress reliever. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 8: Cigarettes enhance the function of smokers’ brains. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 9: Doctors exaggerate the harm of smoking. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| 10: A place with an ashtray is a place where one can smoke. | DN(0) | PN(1) | PY(2) | DY(3) |

| Questions | Options | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| 1. How many cigarettes per day do you smoke? | 31 or more | 3 |

| 21–30 | 2 | |

| 11–20 | 1 | |

| 10 or less | 0 | |

| 2. How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette? | Within 5 min | 3 |

| 6–30 min | 2 | |

| 31–60 min | 1 | |

| After 60 min | 0 | |

| 3. Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden? | Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 | |

| 4. Which cigarette would you hate most to give up? | The first in the morning | 1 |

| All others | 0 | |

| 5. Do you smoke more frequently during the first hours after waking than during the rest of the day? | Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 | |

| 6. Do you smoke when you are so ill that you are in bed most of the day? | Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Conventional Cigarettes (n = 61) | Non-Conventional Cigarettes (n = 30) | Dual Users (n = 91) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 157) | 54 (88.5%) | 26 (86.7%) | 77 (84.6%) |

| Female (n = 25) | 7 (11.5%) | 4 (13.3%) | 14 (15.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aoike, M.; Mori, Y.; Aoyama, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Kozai, H.; Shigeno, Y.; Kawamura, H.; Tsurudome, M.; Ito, M. Nicotine Dependence among College Students Uninterested in Smoking Cessation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065135

Aoike M, Mori Y, Aoyama Y, Tanaka M, Kozai H, Shigeno Y, Kawamura H, Tsurudome M, Ito M. Nicotine Dependence among College Students Uninterested in Smoking Cessation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):5135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065135

Chicago/Turabian StyleAoike, Makoto, Yukihiro Mori, Yuka Aoyama, Mamoru Tanaka, Hana Kozai, Yukihiro Shigeno, Hatsumi Kawamura, Masato Tsurudome, and Morihiro Ito. 2023. "Nicotine Dependence among College Students Uninterested in Smoking Cessation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 5135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065135

APA StyleAoike, M., Mori, Y., Aoyama, Y., Tanaka, M., Kozai, H., Shigeno, Y., Kawamura, H., Tsurudome, M., & Ito, M. (2023). Nicotine Dependence among College Students Uninterested in Smoking Cessation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065135