Paternal Experiences of Perinatal Loss—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

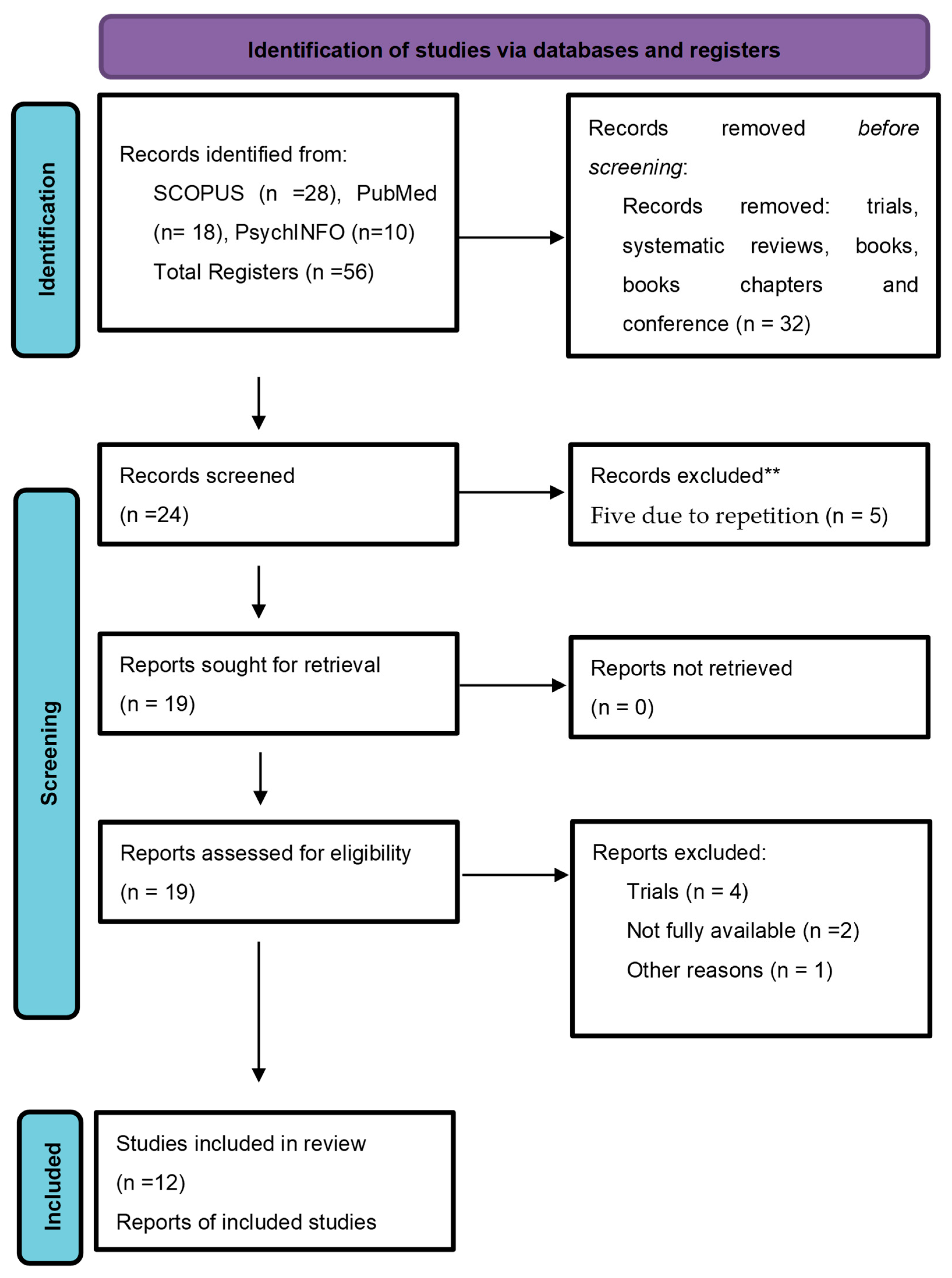

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Charting Process

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

Relevant Topics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kersting, A.; Wagner, B. Complicated grief after perinatal loss. Dialog Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, P.R. The Disenfranchisement of Perinatal Grief: How Silence, Silencing and Self-Censorship Complicate Bereavement (a Mixed Methods Study). Omega J. Death Dying 2021, 00302228211050500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setubal, M.; Bolibio, R.; Jesus, R.; Benute, G.; Gibelli, M.; Bertolassi, N.; Barbosa, T.; Gomes, A.; Figueiredo, F.; Ferreira, R.; et al. A systematic review of instruments measuring grief after perinatal loss and factors associated with grief reactions. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 19, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez-Doren, F.; Lucchini-Raies, C.; Bertolozzi, M.R. Significado y participación social del hombre al transformarse en padre por primera vez. Andes Pediatr. 2021, 92, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizcano-Pabón, L.D.M.; Moreno-Fergusson, M.E.; Palacios, A.M. Experience of Perinatal Death from the Father’s Perspective. Nurs. Res. 2019, 68, E1–E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunen, N.B.; Jomeen, J.; Poat, A.; Xuereb, R.B. ‘A small person that we made’—Parental conceptualisation of the unborn child: A constructivist grounded theory. Midwifery 2021, 104, 103198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarto, A.; Duaso, M.J. Fathers’ experiences of fetal attachment: A qualitative study. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 43, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrskylä, M.; Margolis, R. Happiness: Before and After the Kids. Demography 2014, 51, 1843–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sola, C.; Camacho-Ávila, M.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Jiménez-López, F.R.; Hernández-Sánchez, E.; Conesa-Ferrer, M.B.; Granero-Molina, J. Impact of Perinatal Death on the Social and Family Context of the Parents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-F.; Cheng, H.-R.; Chen, Y.-P.; Yang, S.-F.; Cheng, P.-T. Grief reactions of couples to perinatal loss: A one-year prospective follow-up. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 5133–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, S.; Obst, K.L.; Due, C.; Oxlad, M.; Middleton, P. Overwhelming and unjust: A qualitative study of fathers’ experiences of grief following neonatal death. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, M.J.; Baker, J.N.; Snyder, I.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Kaye, E.C. Grief and Bereavement in Fathers After the Death of a Child: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020040386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, L.; Lasker, J.; Toedter, L. Measuring grief: A short version of the perinatal grief scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 1989, 11, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.K.; Arora, N.K.; Gaikwad, H.; Chellani, H.; Debata, P.; Rasaily, R.; Meena, K.R.; Kaur, G.; Malik, P.; Joshi, S.; et al. Grief reaction and psychosocial impacts of child death and stillbirth on bereaved North Indian parents: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0240270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, K.L.; Oxlad, M.; Due, C.; Middleton, P. Factors contributing to men’s grief following pregnancy loss and neonatal death: Further development of an emerging model in an Australian sample. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanacıoğlu-Aydın, B.; Erdur-Baker, O. Pregnancy loss experiences of couples in a phenomenological study: Gender differences within the Turkish sociocultural context. Death Stud. 2021, 46, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.Q.; Oka, M.; Robinson, W.D. Pain without reward: A phenomenological exploration of stillbirth for couples and their hospital encounter. Death Stud. 2019, 45, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Ávila, M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Jiménez-López, F.R.; Granero-Molina, J.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, E.; Fernández-Sola, C. Parents’ Experiences About Support Following Stillbirth and Neonatal Death. Adv. Neonatal Care 2020, 20, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, E.A.; Mastroyannopoulou, K.; Rushworth, I. Parents experience of using “cold” facilities at a children’s hospice after the death of their baby: A qualitative study. Death Stud. 2020, 46, 1501–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleschini, S.; Aubuchon, O.; Champeau, L.; Matte-Gagné, C. History of perinatal loss: A study of psychological outcomes in mothers and fathers after subsequent healthy birth. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 280, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrales, L.L.; Cacciatore, J.; Jonas-Simpson, C.; Dharamsi, S.; Ascher, J.; Klein, M. What bereaved parents want health care providers to know when their babies are stillborn: A community-based participatory study. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Serrano, P.; Pedraz-Marcos, A.; Solís-Muñoz, M.; Palmar-Santo, A. The experience of mothers and fathers in cases of stillbirth in Spain. A qualitative study. Midwifery 2019, 77, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Due, C.; Chiarolli, S.; Riggs, D.W. The impact of pregnancy loss on men’s health and wellbeing: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Robb, M.; Murphy, S.; Davies, A. New understandings of fathers’ experiences of grief and loss following stillbirth and neonatal death: A scoping review. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, H.M.; Topping, A.; Coomarasamy, A.; Jones, L. Men and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 30, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Basanta, S.; Coronado, C.; Movilla-Fernández, M.J. Barreras y facilitadores en el afrontamiento de la pérdida perinatal: Una meta-etnografía. CIAIQ 2019, 2, 994–999. Available online: https://proceedings.ciaiq.org/index.php/CIAIQ2019/article/view/2173/2101 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Karali, H.F.; Farhad, E.S.; Zaigham, M.T.; Wen, P.Y.; Parveena, S.; Siong, T.J. Male partners’ expected response, coping mechanisms, social and health institutions expectations after early pregnancy loss: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 5, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Type of Study | Sample | Type of Death | Time of Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lizcano et al., (2019) [5] | Colombia | Qualitative | 15 Spanish-speaking men over 18 years (average age not reported) | Gestational | No more than one year |

| Fernández-Solá et al., (2020) [9] | Spain | Qualitative | 8 fathers and 13 mothers of legal age (average age not reported) | Gestational | 3 months to 5 years |

| Das et al., (2021) [15] | India | Mixed exploratory | 49 fathers and 50 mothers (average age not reported). | Gestational | 6 to 9 months |

| Obst et al., (2021) [16] | Australia | Quantitative | 228 heterosexual males over 18 years | Gestational and neonatal | The past 20 years |

| Azeez et al., (2022) [11] | Australia | Qualitative exploratory | 10 men over the age of 18; age ranged from 31 to 42 years (M = 32, SD = 3.4). | Neonatal | From 1 to 12 years |

| Tanacıoglu-Aydın & Erdur-Baker (2022) [17] | Turkey | Phenomenological–qualitative | 10 couples, a total of 20 subjects (10 men and 10 women) over the age of 18 | Gestational | 4 months to 6 years |

| King et al., (2019) [18] | USA | Qualitative | 8 couples (8 men and 8 women), mean age for women = 29.88, SD = 6.06; for men = 31.63, SD = 6.65 | Gestational | 3 to 6.5 years |

| Camacho et al., (2020) [19] | Spain | Qualitative | 21 subjects (13 mothers and 8 fathers), mean age of 35.6 years. | Gestational and neonatal | Not mentioned |

| Norton et al., (2020) [20] | United kingdom | Qualitative | 7 participants (4 mothers and 3 fathers) | Neonatal | Not mentioned |

| Faleschini et al., (2021) [21] | Canada | Quantitative | 92 dyads (father and mother) = 184. Women had a mean age = 31.19, SD = 4.24; the mean age for men = 33.17, SD = 4.21. | Gestational | Not mentioned |

| Farrales et al., (2020) [22] | Canada | Qualitative | 15 women and 12 fathers over 19 years old. The median age was 39 years. | Gestational | 2 months to 20 years |

| Martínez-Serrano et al., (2019) [23] | Spain | Qualitative | 7 mothers and 4 fathers over 18 years old. | Gestational | > 18 months |

| Study | Objective | Identified Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Lizcano et al., (2019) [5] | To understand and describe the meaning of perinatal death in a sample of parents from northeastern Colombia. | (1) The experience of loss. (2) The irreparable loss. (3) Overcoming loss. |

| Fernández-Solá et al., (2020) [9] | To explore the social and psychological impacts of infant death on the parents and their families in northern India. | (1) The impact on family dynamics. (2) The impact on the social environment. |

| Das et al., (2021) [15] | To document the grief and coping experiences of Indian parents after stillbirth and neonatal death. | (1) Anticipation and expression of grief. (2) Impact of grief. (3) Coping mechanisms. (4) Socio-cultural practices and norms. |

| Obst et al., (2021) [16] | To determine factors associated with grief intensity afterpregnancy loss and neonatal death, as well as factors associated with intuitive and instrumental grief styles. | (1) Grief intensity is related to gestational age. (2) Social support and the bond with the baby during pregnancy are related to less intense mourning. |

| Azeez et al., (2022) [11] | To explore the grieving experiences of fathers following neonatal death. | (1) Grief as a complicated experience. (2) The multidimensionality of grief. (3) Sense of injustice. |

| Tanacıoglu-Aydın & Erdur-Baker (2022) [17] | To identify the experiences of pregnancy loss among couples. | (1) The sociocultural context before the pregnancy. (2) The sociocultural context after the loss. |

| King et al., (2019) [18] | To understand the hospital experiences of fetal death for parents, particularly men, and to understand how couples experienced it together. | (1) Hospital care. (2) Grief and loss. (3) The relationships with their partner and family. (4) Long-term impacts. |

| Camacho et al., (2020) [19] | To describe and understand the experiences of parents in relation to professional and social support after fetal and neonatal death. | (1) Unauthorized grief. (2) Lack of social acknowledgement. (3) Socially, the loss is minimized. |

| Norton et al., (2020) [20] | To discover the experiences of parents whose children died in the perinatal period and who used cold cribs for preservation. | (1) Having space and time to be able to adjust to the loss. (2) Being able to care for the baby for a while. (3) Being able to spend family time with the baby. (4) Having the baby close. (5) Creating memories. (6) Social perception of being able to spend time with the deceased baby. |

| Faleschini et al., (2021) [21] | To examine associations between perinatal losses, psychological symptoms, and parental stress in mothers and fathers six months after the birth of a subsequent healthy child. | (1) Various losses increase psychological symptoms. (2) Risks may be influenced by gender stigmas, socialization, and biological and physiological differences between men and women. (3) Men reported fewer symptoms than women. |

| Farrales et al., (2020) [22] | To explore the experiences of bereaved parents during their interactions with healthcare providers during and after the stillbirth of an infant. | (1) The acknowledgement of the baby as an irreplaceable individual. (2) The acknowledgement of fathers’ paternity and grief. (3) The acknowledgement of traumatic grief. (4) The acknowledgement of the need for specialized support. |

| Martínez-Serrano et al., (2019) [23] | To explore the experiences of both mothers and fathers regarding care received during childbirth in cases of stillbirth. | (1) Grief denial. (2) The paradox of life and death. (3) Guilt. (4) The experience and overcoming of loss. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mota, C.; Sánchez, C.; Carreño, J.; Gómez, M.E. Paternal Experiences of Perinatal Loss—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064886

Mota C, Sánchez C, Carreño J, Gómez ME. Paternal Experiences of Perinatal Loss—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064886

Chicago/Turabian StyleMota, Cecilia, Claudia Sánchez, Jorge Carreño, and María Eugenia Gómez. 2023. "Paternal Experiences of Perinatal Loss—A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064886

APA StyleMota, C., Sánchez, C., Carreño, J., & Gómez, M. E. (2023). Paternal Experiences of Perinatal Loss—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064886