The Relationship of Parent Support and Child Emotional Regulation to School Readiness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Children’s Emotion Regulation Development: The Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Family Stress Model

2.1.2. Bioecological Model of Human Development

2.2. Children’s Emotion Regulation Development: Perspectives from Empirical Studies

2.2.1. Child Emotion Regulation: Definition and Significance

2.2.2. Child Emotion Regulation: The Role of Supportive Parenting

2.2.3. Linking Parent Supportiveness to Low-Income Children’s Outcomes

2.3. The Current Study

3. Method

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measures

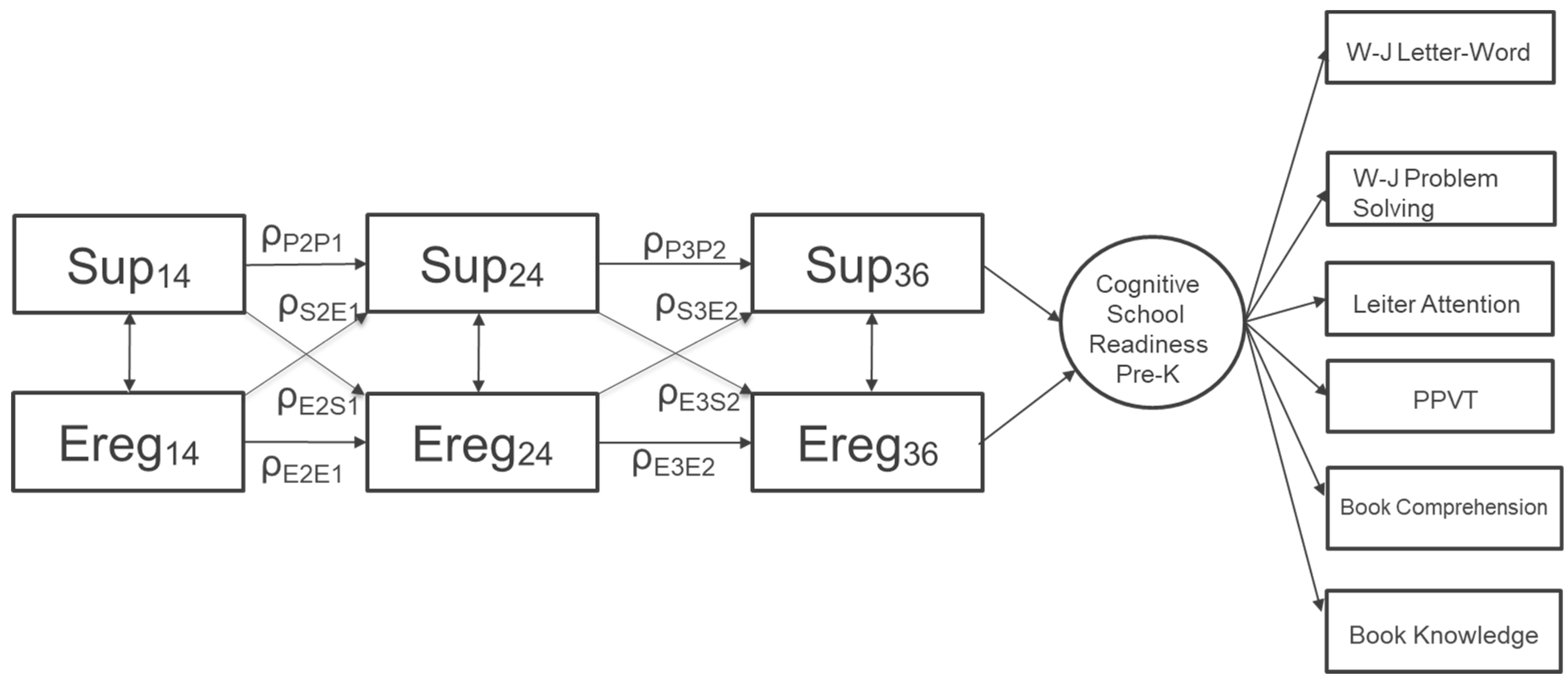

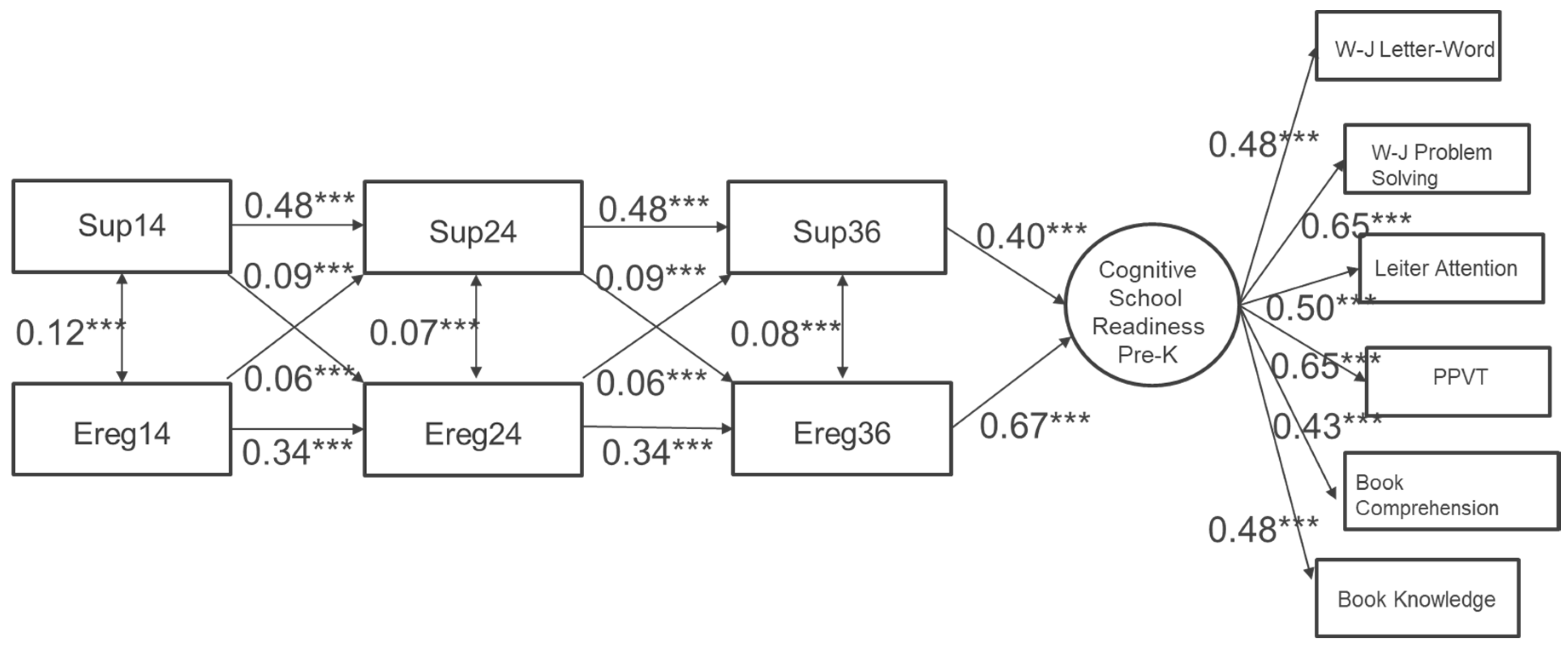

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Generalized Autoregressive Models

5. Discussion

5.1. How Does the Intra-Individual Developmental Trajectory of Parent Supportiveness Change over Time?

5.2. How Do EHS Program Status and Race/Ethnicity Predict the Parent Supportiveness Outcome?

5.3. How Does the Intra-Individual Developmental Trajectory of Child Emotion Regulation Change over Time?

5.4. How Well Do the Transactional Effects of Parent Supportiveness and Child Emotion Regulation Predict Age Five Cognitive School Readiness?

5.5. How Do EHS Program Status and Race/Ethnicity Predict the Child Cognitive School Readiness?

5.6. Implications for Early Childhood Practices

5.7. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kagan, S.L.; Moore, E.K.; Bredekamp, S. Reconsidering Children’s Early Development and Learning: Toward Common Views and Vocabulary; National Education Goals Panel: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Aber, L.; Morris, P.; Raver, C. Children, Families and Poverty: Definitions, Trends, Emerging Science and Implications for Policy. Soc. Policy Rep. 2012, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, G.W.; Kim, P. Childhood Poverty, Chronic Stress, Self-Regulation, and Coping. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocknek, E.L.; Brophy-Herb, H.E.; Banerjee, M. Effects of parental supportiveness on toddlers’ emotion regulation over the first three years of life in a low-income African American sample. Infant Ment. Health J. Off. Publ. World Assoc. Infant Ment. Health 2009, 30, 452–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, L.K.; Bub, K.L. The influence of family routines on the resilience of low-income preschoolers. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 35, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajicek-Farber, M.L.; Mayer, L.M.; Daughtery, L.G.; Rodkey, E. The buffering effect of childhood routines: Longitudinal connections between early parenting and prekindergarten learning readiness of children in low-income families. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2014, 40, 699–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, K.M.; Leventhal, T. Beyond neighborhood poverty: Family management, neighborhood disorder, and adolescents’ early sexual onset. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, M.J.; Kotch, J.B.; Lee, L.-C.; Augsberger, A.; Hutto, N. A cumulative ecological–transactional risk model of child maltreatment and behavioral outcomes: Reconceptualizing early maltreatment report as risk factor. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 2392–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouglioti, C.; Cole, R.; Moskow, M. Single mothers’ views of young children’s everyday routines: A focus group study. J. Community Health Nurs. 2011, 28, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.D.; Low, C.M. Chaotic living conditions and sleep problems associated with children’s responses to academic challenge. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Donnellan, M.B. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F.; McAdoo, H.P.; García Coll, C. The home environments of children in the United States part I: Variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1844–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L. Emotion-related regulation: Sharpening the definition. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, S.A.; Herberle, A.E.; Carter, A.S. Social-Emotional School Readiness: How Do We Ensure Children Are Ready to Learn? Zero Three (J) 2012, 33, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, C.; Diamond, A. Biological processes in prevention and intervention: The promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Dev. Psychopathol. 2008, 20, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.-J.; Peterson, C.A.; DeCoster, J. Parent–child interaction, task-oriented regulation, and cognitive development in toddlers facing developmental risks. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 34, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Little, T.D. Influences of children’s and adolescents’ action-control processes on school achievement, peer relationships, and coping with challenging life events. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2011, 2011, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, P.A.; Reavis, R.D.; Keane, S.P.; Calkins, S.D. The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. J. Sch. Psychol. 2007, 45, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrill, S.A.; Deater-Deckard, K. Task orientation, parental warmth and SES account for a significant proportion of the shared environmental variance in general cognitive ability in early childhood: Evidence from a twin study. Dev. Sci. 2004, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Steinberg, L.; Myers, S.S.; Robinson, L.R. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy-Herb, H.E.; Schiffman, R.F.; Bocknek, E.L.; Dupuis, S.B.; Fitzgerald, H.E.; Horodynski, M.; Onaga, E.; Van Egeren, L.A.; Hillaker, B. Toddlers’ social-emotional competence in the contexts of maternal emotion socialization and contingent responsiveness in a low-income sample. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, G.M.; Grych, J.H. Capturing the family context of emotion regulation: A family systems model comparison approach. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 34, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.W.E.; Logsdon, M. Maternal Sensitivity: A Scientific Foundation for Practice; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.E.; Landry, S.H.; Swank, P.R. The influence of early patterns of positive parenting on children’s preschool outcomes. Early Educ. Dev. 2000, 11, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, R.S.; Benner, A.D.; Biesanz, J.C.; Clark, S.L.; Howes, C. Family and social risk, and parental investments during the early childhood years as predictors of low-income children’s school readiness outcomes. Early Child. Res. Q. 2010, 25, 432–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabes, R.A.; Leonard, S.A.; Kupanoff, K.; Martin, C.L. Parental coping with children’s negative emotions: Relations with children’s emotional and social responding. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazan-Cohen, R.; Raikes, H.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Ayoub, C.; Pan, B.A.; Kisker, E.E.; Roggman, L.; Fuligni, A.S. Low-income children’s school readiness: Parent contributions over the first five years. Early Educ. Dev. 2009, 20, 958–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikes, H.A.; Robinson, J.L.; Bradley, R.H.; Raikes, H.H.; Ayoub, C.C. Developmental trends in self-regulation among low-income toddlers. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy-Herb, H.E.; Zajicek-Farber, M.L.; Bocknek, E.L.; McKelvey, L.M.; Stansbury, K. Longitudinal connections of maternal supportiveness and early emotion regulation to children’s school readiness in low-income families. J. Soc. Soc. Work. Res. 2013, 4, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.S.; Brady-Smith, C.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S.; Bradley, R.H.; Chazan-Cohen, R.; Boyce, L.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Patterns of supportive mothering with 1-, 2-, and 3-year-olds by ethnicity in Early Head Start. Parenting 2013, 13, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocknek, E.L.; Brophy-Herb, H.E.; Fitzgerald, H.; Burns-Jager, K.; Carolan, M.T. Maternal psychological absence and toddlers’ social-emotional development: Interpretations from the perspective of boundary ambiguity theory. Fam. Process 2012, 51, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Gil, J.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S. Family resources and parenting quality: Links to children’s cognitive development across the first 3 years. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, J.M.; Kisker, E.E.; Ross, C.; Raikes, H.; Constantine, J.; Boller, K.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Chazan-Cohen, R.; Tarullo, L.B.; Brady-Smith, C. The effectiveness of early head start for 3-year-old children and their parents: Lessons for policy and programs. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Administration for Children and Families. Head Start Impact Study and Follow-Up, 2000–2009; United States Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Mplus 7.4 1998–2015. Available online: http://www.statmodel.com/verhistory.shtml (accessed on 19 August 2013).

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nellis, L.; Gridley, B.E. Review of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development—Second edition. J. Sch. Psychol. 1994, 32, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.S.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Mother–child interactions in Early Head Start: Age and ethnic differences in low-income dyads. Parenting 2013, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, R.W.; McGrew, K.S.; Mather, N. Woodcock-Johnson III NU Complete; Riverside Publishing: Rolling Meadows, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, D. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-IIIA; American Guidance Services: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roid, G.; Nellis, L.; McLellan, M. Assessment with the Leiter International Performance Scale—Revised and the S-BIT. In Handbook of Nonverbal Assessment; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 113–140. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, J.; Stipek, D. The emergence of gender differences in children’s perceptions of their academic competence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 26, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Curran, P.J. Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models a synthesis of two traditions. Sociol. Methods Res. 2004, 32, 336–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, E.; McArdle, J. Alternative structural models for multivariate longitudinal data analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 493–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Iruka, I.U. Ethnic variation in the association between family structures and practices on child outcomes at 36 months: Results from Early Head Start. Early Educ. Dev. 2009, 20, 148–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Martin, A.; Klute, M.M. III. Impacts of Early Head Start participation on child and parent outcomes at ages 2, 3, and 5. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2013, 78, 36–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbe, A.M.; Kiel, E.J.; Buss, K.A. Toddlers’ context-varying emotions, maternal responses to emotions, and internalizing behaviors. Emotion 2011, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N (%) or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Family Race | |

| White | 1086 (37%) |

| African American | 1014 (34%) |

| Hispanic | 692 (23%) |

| Other 1 | 133 (5%) |

| Number of Family Risks 2 | |

| 0–2 | 1129 (38%) |

| 3 | 835 (28%) |

| 4–5 | 704 (24%) |

| Primary Caregiver Role | |

| Mother | 2960 (99%) |

| Parent Educational Attainment | |

| <12 years of schooling | 1367 (45.9%) |

| 12 years of school or GED | 822(27.6%) |

| >12 years of schooling | 681(22.9%) |

| Child Gender | |

| Male | 1502 (51%) |

| Female | 1446 (49%) |

| Child Age (in months) | |

| 14 M | 15 (1.2) |

| 24 M | 25 (1.3) |

| 36 M | 37 (1.1) |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 14 M SUP | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.27 * | 0.23 * | 0.35 * | 0.22 * | 0.13 | |||||||

| 2. 24 M SUP | 0.52 * | 1.00 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.32 * | 0.16 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 3. 36 M SUP | 0.42 * | 0.49 * | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.25 * | 0.22 * | 0.35 * | 0.17 | 0.19 | |||||

| 4. 14 M EMR | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.08 | ||||

| 5. 24 M EMR | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.28 * | 1.00 | 0.20 * | 0.27 * | 0.24 * | 0.24 * | 0.18 | 0.18 | |||

| 6. 36 M EMR | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.37 * | 1.00 | 0.25 * | 0.38 * | 0.33 * | 0.31 * | 0.26 * | 0.31 * | ||

| 7. W-J Letter Word | 1.00 | 0.53 * | 0.38 * | 0.45 * | 0.34 * | 0.29 * | ||||||||

| 8. W-J Problem Solving | 1.00 | 0.50 * | 0.65 * | 0.48 * | 0.40 * | |||||||||

| 9. Leiter Attention | 1.00 | 0.47 * | 0.37 * | 0.35 * | ||||||||||

| 10. PPVT | 1.00 | 0.48 * | 0.45 * | |||||||||||

| 11. Book Knowledge | 1.00 | 0.38 * | ||||||||||||

| 12. Book Comprehension | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 13. Program status (dummy) | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 1.00 | |

| 14. Family race (dummy) | −0.16 | −0.13 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.16 | −0.06 | −0.22 | −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Mean | 3.96 | 4.05 | 4.02 | 3.71 | 3.71 | 3.94 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Variance | 1.09 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | ||

| Minimum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.33 | −3.38 | −4.57 | −2.93 | −3.35 | −2.42 | −2.84 | ||

| Maximum | 7.00 | 7.00 | 6.33 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 3.40 | 2.19 | 2.60 | 3.90 | 1.43 | 1.07 | ||

| Sample size | 2132 | 1513 | 789 | 2132 | 1513 | 789 | 1504 | 1505 | 1414 | 1483 | 1491 | 1485 | 2100 | 2100 |

| SUP (14 m) | EMR (14 m) | SUP (24 m) | EMR (24 m) | SUP (36 m) | EMR (36 m) | Cognitive School Readiness (Pre-K) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (s.e.) | p | b (s.e.) | p | b (s.e.) | p | b (s.e.) | p | b (s.e.) | p | b (s.e.) | p | b (s.e.) | p | |

| 1. Race | −0.19 (0.03) | 0.00 | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.17 | −0.08 (0.03) | 0.01 | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.15 | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.87 | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.69 | −0.23 (0.04) | 0.00 |

| 2. Program Status | 0.10 (0.05) | 0.03 | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.32 | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.51 | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.57 | 0.19 (0.06) | 0.00 | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.70 | −0.12 (0.07) | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, M.-L.; Faldowski, R.A. The Relationship of Parent Support and Child Emotional Regulation to School Readiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064867

Lin M-L, Faldowski RA. The Relationship of Parent Support and Child Emotional Regulation to School Readiness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064867

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Mei-Ling, and Richard A. Faldowski. 2023. "The Relationship of Parent Support and Child Emotional Regulation to School Readiness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064867

APA StyleLin, M.-L., & Faldowski, R. A. (2023). The Relationship of Parent Support and Child Emotional Regulation to School Readiness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064867