Changing the Underlying Conditions Relevant to Workplace Bullying through Organisational Redesign

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework for the Intervention

3. The Intervention

4. Methodology

4.1. Intervention Context

4.2. Intervention Phases and Data Sources

4.3. Quantitative Methodology

4.3.1. Participants

4.3.2. Quantitative Survey Measures

4.3.3. Internal Company Data

4.3.4. Quantitative Analysis

4.4. Qualitative Methodology

4.4.1. Qualitative Design

4.4.2. Qualitative Sampling

4.4.3. Qualitative Materials

4.4.4. Qualitative Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Quantitative Findings

5.1.1. Aggregation of Data to Store- and Department-Level

5.1.2. Descriptive Statistics

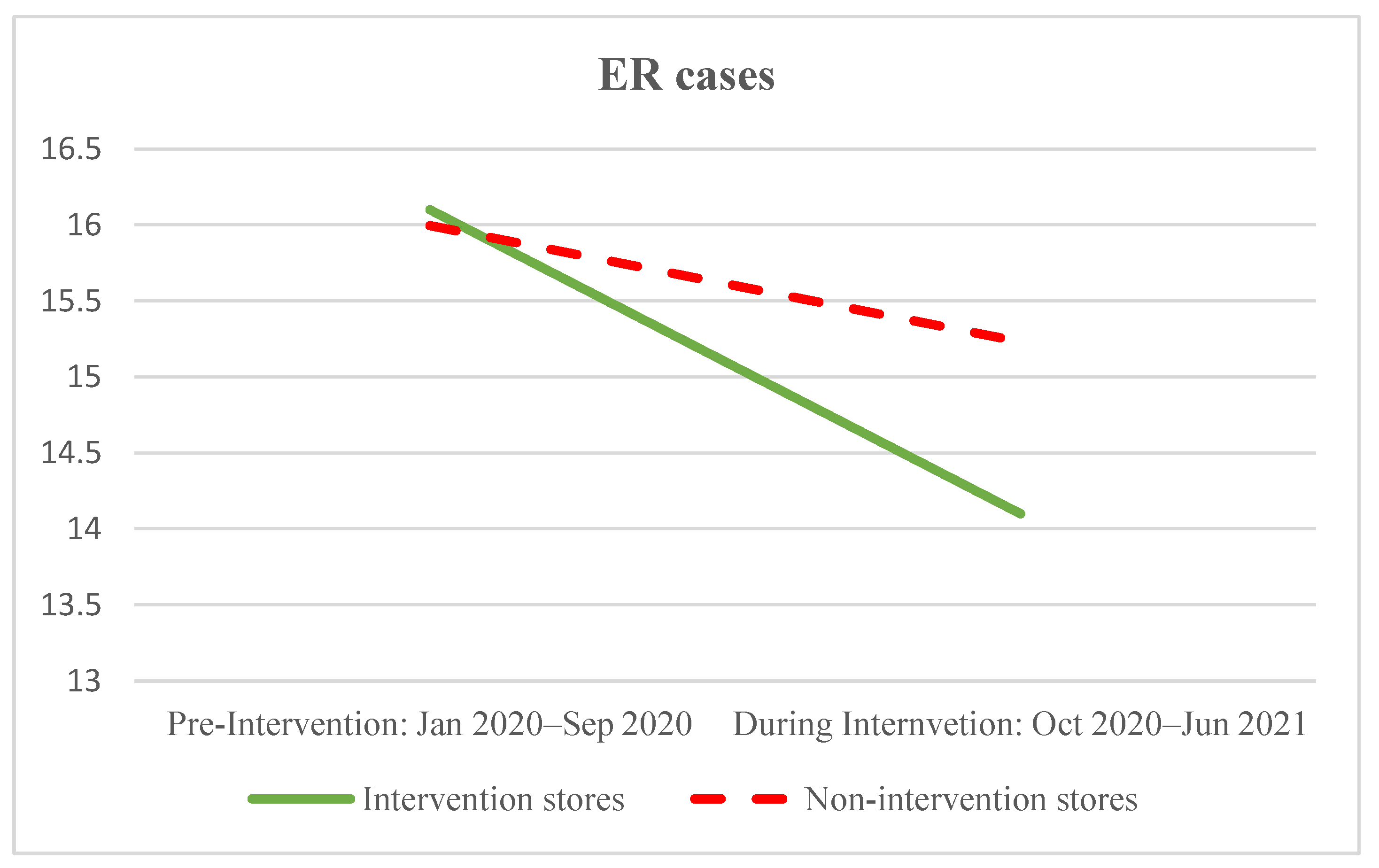

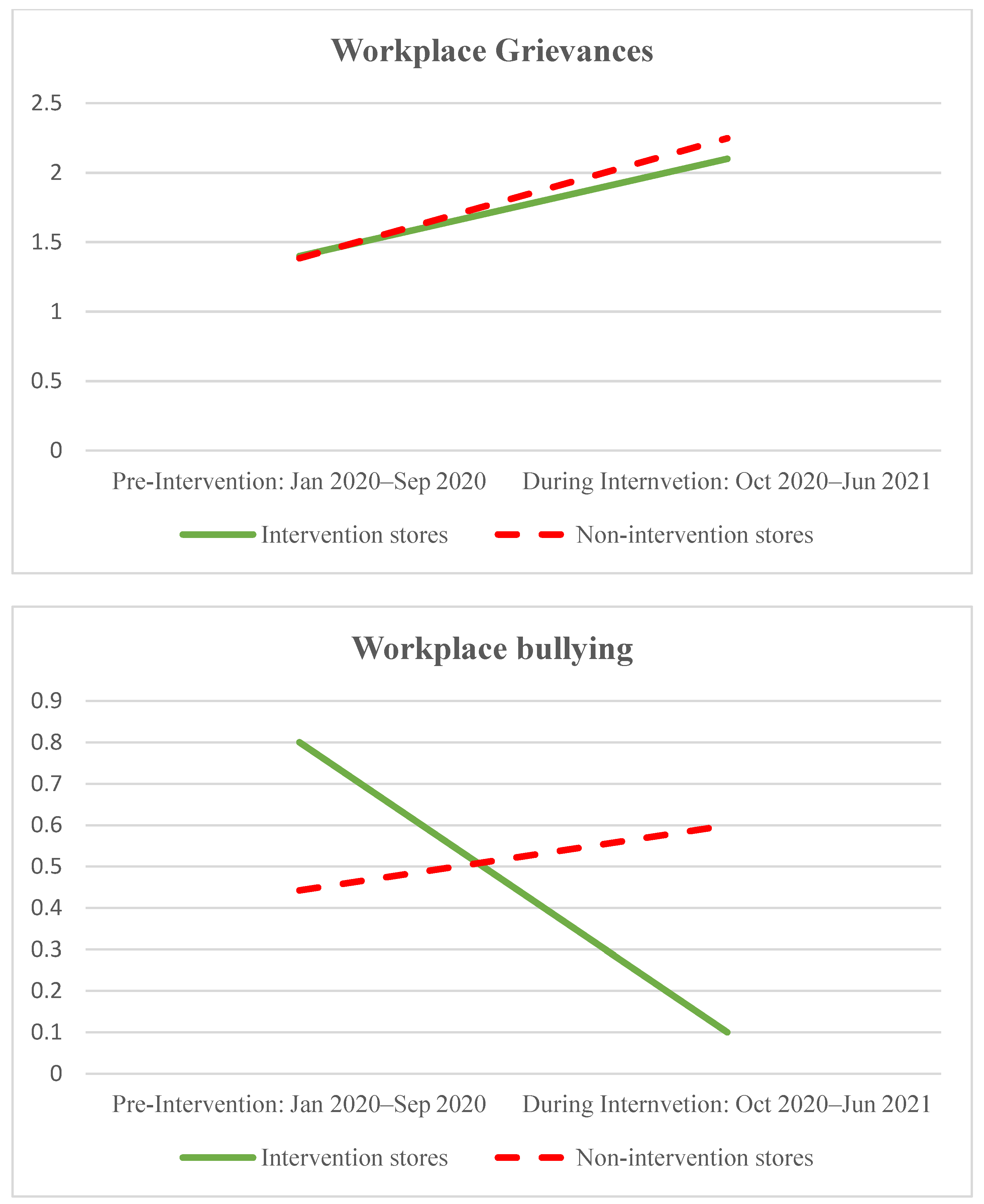

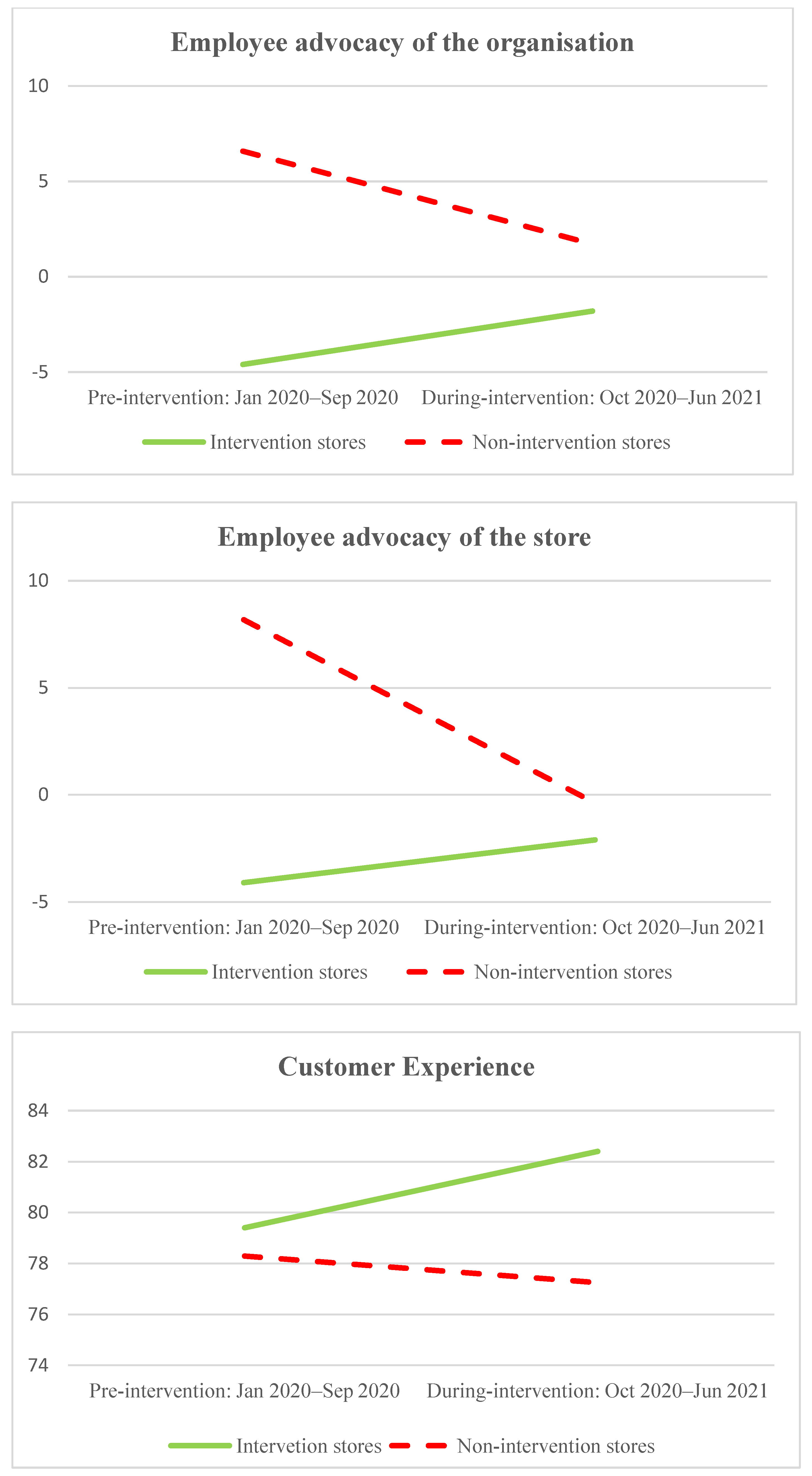

5.1.3. Intervention Effectiveness

5.1.4. Intervention Mechanisms

5.2. Qualitative Analysis

5.2.1. Safety Net

“However, just being involved in the workshops and being involved in a survey where people are actually listening and responding, where group managers and store [managers], and [HR] partners are paying extra attention, where we’ve got an extra project team and me and other people going in and checking in on them and asking questions and providing support. I think yeah, I think that’s the most valuable part is just they see we’re trying and we see, they see we care. And then on the back of that they have that attitude towards their own team, so a lot of the time the store managers see we’re trying and they’re able to go back to their team and have the same kind of attitude and just show they’re trying.”HR Partner

“and there was a lot of seniority in the room as well and we had [HR partner] and a few other higher ups and what not, so we had that kind of, I guess that safety net where we’re seeing our higher ups there, obviously it’s interesting, obviously it’s something new coming.”Team member

“I’m in total agreement, yeah I think that’s exactly right. I think I myself, definitely if I see a higher up there, I definitely take something more seriously, because it’s kind of hard to tell what is going to be the next thing we need to focus on, because so many different initiatives and so many different things happen, all year around this business is changing an incredible amount, really, really quickly, at pace, and apparently that’s what they call it, but it’s—yeah, seeing higher ups there [allows me to invest]”Manager

“so, the store managers understand that part of the problem is that people don’t see action and they don’t feel like they’re being heard. So just a shift to go to actually try things and show the team that they’re listening, and that’s what’s kind of shifted them to just trying little things and implementing them rather than waiting and sitting back. And you know, they [managers] might be planning in their office what to do about it, but if there’s no action the team member doesn’t know and they just feel unheard. I think that’s, to me that’s the difference, they’re trying to show to the team that they’re being listened to.”HR Partner

“…we’ve just kind of been able to let team open themselves up a little bit more to us and we’ve been kind of able to ask what’s up, what’s wrong, and people have been telling us, as opposed to kind of that cold shoulder and the feeling of nervousness that team members were feeling.”Manager

“We have really been pushing team leaders and managers to manage people, not manage the job. Focus on speaking to people and working with people on the way that works best for them. Giving coaching on how to address challenges and complexities.”Manager

5.2.2. Participatory Change

“my selling point [for investing in change] that I spoke to everyone, and why a lot of the people that are around me were hyped about it, was that I just said this is for us, this is for our future, this is for us working at [the organisation] in 10–15 years, like not all of them, obviously but those of us who are still going to be with the company in leadership positions, in whatever, that the company is going to start listening and showing people that this is a positive change and we’re moving forward, so they’ve got to be part of it, it’s so important to be a part of these changes…”Manager

“… and also empowering the team by making just a team member the champion I think would just change the culture on the shop floor level, like on the team member level because they see that one person being able to make changes and they’ll know that they can do it too.”Manager

“On the back of recognition initiatives, the team gave feedback asking the store manager to recognise their [leaders] more, so that ripples down to the team, so role modelling that recognition is starting that this week”Manager

“We’re seeing that, right? Like they’re, it’s not ‘oh we have this issue in store, we’re so annoyed’, it’s ‘we have this issue, let’s ask the team how we can fix it’—like a solution to be solved rather than a problem.”HR Partner

5.2.3. Team Unity

“Yeah, one whole team not just your—like you’re a team player not a department player, you’re about the whole store, not just your department; that’s a big difference I’ve noticed. Yeah, that’s us.”Team member

“I think we were kind of not really a team, but we were like several teams, but now I think we’ve had that opportunity to really grow and develop, and send people across and cross-train people, so it’s now more of that one team mentality as well.”Manager

“Yeah, I feel the vibe in the whole store is a lot supportive and everyone recognises each other’s hard work no matter what level you’re at; so doesn’t matter if you’re just a team member, noticing another team member working really hard and you’re like great job there [name], or whoever; everyone’s just a lot more supportive and we just have each other’s back a lot more […] we’re more like a family.”Manager

Today was a good example: we made some changes in [a department]. To see the whole team help without being asked was so humbling, to see it happen automatically.Manager

“There shouldn’t be any team members in store now that you don’t feel comfortable to say hello to. Massive improvement there. Especially with team members that went to the initial session [workshop]—it brought them out of their shell.”Manager

“Our new catch phrase is: ‘More hands make light work.’ So we have started swarm filling, […] and there’s new emphasis on working as ‘one team,’ and we’ve started doing department huddles and took department out of store to hash out their issues. They weren’t being communicated to about the WHYs and they needed that!”Manager

5.2.4. Positive Change Trajectory

“Like the other stores [are seeing], the little things make the difference—thank yous, an open-door policy.”Team member

“…there was a lot of team members who had been with the business for quite some time, so it was kind of nice to show them the progression of the business, especially regarding mental health and being comfortable with your team and being comfortable with your leaders, especially.”Manager

“What I’m saying is that like with this push and seeing such a positive result and a positive, and noticing the whole team light up when you talk about mental health and how you can better assist them. It’s in our—I guess it’s in my best interest as a leader, and the project’s best interest to actually put in that extra bit of effort, because it’s the only way you’re going to get the ball rolling.”Manager

“And even if it doesn’t work and we’ve heard examples of where they’ve implemented stuff and it didn’t work out, at least they can, they showed to the team that ‘hey, we tried it, we listened to you, didn’t work, if you have other suggestions let us know and we can try again’.”Operations

“We are noticing that the team are starting to help each other as well, working together as one team across the store.”Manager

“It’s the little things we now do differently, we’re seeing a change in culture, for everyone not just team leaders. Feedback has been very positive from the team.”Manager

“Our customers are noticing as well; we’re currently tracking at 100% team attitude.”

“Involvement and listening to team members—they’ve got so many great ideas. Also they feel pretty good when you run with those ideas. Multi-skilling the team, adding skillsets. They also get excited about doing something new, enjoying the new challenge.”Manager

“The team have learned so much. Breaking down of all silos—broken down barriers between everyone. It’s fantastic to have the extra tools in our toolbox. It’s the little things.”Manager

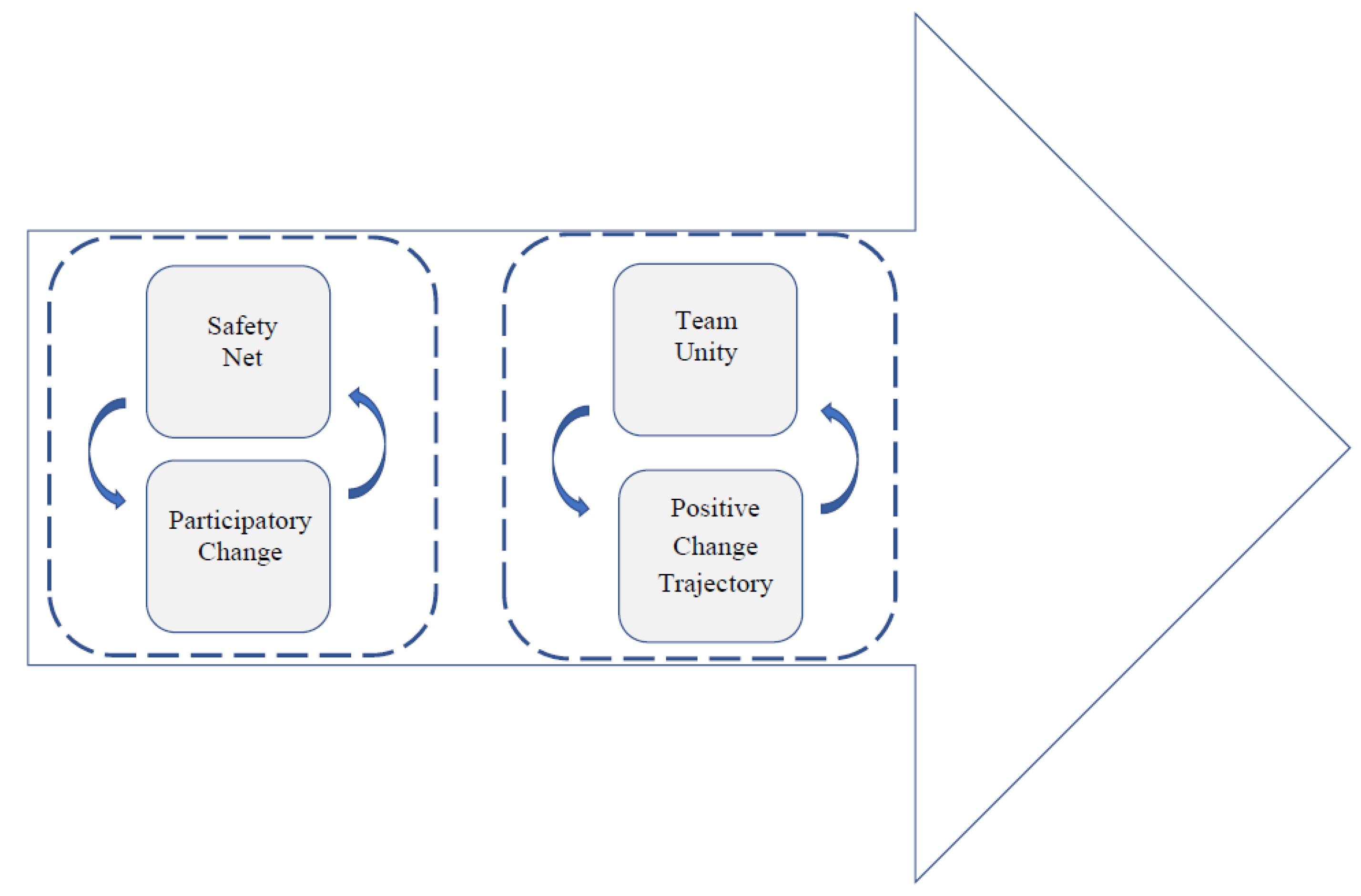

5.2.5. Change Mechanisms as a Dynamic Process Model

“We’ve seen a big dynamic change—everyone being open, wants to work together, wants to be multi-skilled; team members here now want a career at [our organisation].”Manager

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the scandinavian approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuil, B.; Atasayi, S.; Molendijk, M.L. Workplace bullying and mental health: A meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal sata. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijó, F.R.; Gräf, D.D.; Pearce, N.; Fassa, A.G. Risk factors for workplace bullying: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salin, D. The prevention of workplace bullying as a question of human resource management: Measures adopted and underlying organizational factors. Scand. J. Manag. 2008, 24, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponecchia, C.; Wyatt, A. Preventing Workplace Bullying: An Evidence-Based Guide for Managers and Employees, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saam, N.J. Interventions in workplace bullying: A multilevel approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2010, 19, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; MacCurtain, S.; Mannix-McNamara, P. Workplace bullying and incivility: A systematic review of interventions. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2014, 7, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartia, M.; Leka, S. Interventions for the prevention and management of bullying at work: Developments in theory, research, and practice. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace, 2nd ed.; Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 359–379. [Google Scholar]

- Kluger, A.N.; DeNisi, A. The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkanasy, N.M.; Bennett, R.J.; Martinko, M.J. Understanding the High Performance Workplace: The Line between Motivation and Abuse; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karanika-Murray, M.; Biron, C.; Saksvik, P.Ø. Organizational health interventions: Advances in evaluation methodology. Stress Health: J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2016, 32, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neall, A.M.; Tuckey, M.R. A methodological review of research on the antecedents and consequences of workplace harassment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershcovis, M.S.; Reich, T.C.; Niven, K. Workplace Bullying: Causes, Consequences, and Intervention Strategies; SIOP White Paper Series; Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Zahlquist, L.; Mikkelsen, E.G.; Koløen, J.; Einarsen, S.V. Outcomes of a proximal workplace intervention against workplace bullying and harassment: A protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial among Norwegian industrial workers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, M.P.; Day, A.; Oore, D.G.; Spence Laschinger, H.K. Getting better and staying better: Assessing civility, incivility, distress, and job attitudes one year after a civility intervention. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, M.P.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Day, A.; Oore, D.G. The impact of civility interventions on employee social behavior, distress, and attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1258–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osatuke, K.; Moore, S.C.; Ward, C.; Dyrenforth, S.R.; Belton, L. Civility, Respect, Engagement in the Workforce (CREW): Nationwide Organization Development Intervention at Veterans Health Administration. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2009, 45, 384–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponecchia, C.; Branch, S.; Murray, J.P. Development of a taxonomy of workplace bullying intervention types: Informing research directions and supporting organizational decision making. Group Organ. Manag. 2019, 45, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartín, J. Insights into workplace bullying: Psychosocial drivers and effective interventions. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2016, 9, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M.R.; Li, Y.; Neall, A.M.; Chen, P.Y.; Dollard, M.F.; McLinton, S.S.; Rogers, A.; Mattiske, J. Workplace bullying as an organizational problem: Spotlight on people management practices. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 544–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogstad, A.; Torsheim, T.; Einarsen, S.; Hauge, L.J. Testing the work environment hypothesis of bullying on a group level of analysis: Psychosocial factors as precursors of observed workplace bullying. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 60, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Abildgaard, J.S. Organizational interventions: A research-based framework for the evaluation of both process and effects. Work Stress 2013, 27, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, S.J.; Sheridan, D. Effectiveness of bullying and violence prevention programs: A systematic review. AAOHN J. 2010, 58, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M.R.; Neall, A.M. Workplace bullying erodes job and personal resources: Between- and within-person perspectives. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartia, M. The sources of bullying–psychological work environment and organizational climate. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D. Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agervold, M.; Mikkelsen, E.G. Relationships between bullying, psychosocial work environment and individual stress reactions. Work Stress 2004, 18, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, A.; Van den Broeck, A.; De Witte, H. Do demands and resources affect target’s and perpetrators’ reports of workplace bullying? A two-wave cross-lagged study. Work Stress 2011, 25, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. Workplace bullying and its relation with work characteristics, personality, and post-traumatic stress symptoms: An integrated model. Anxiety Stress Coping 2011, 24, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, E.; Coetzee, M. Job demands–resources and flourishing: Exploring workplace bullying as a potential mediator. Psychol. Rep. 2019, 123, 1316–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, P.M.; Burr, H.; Rose, U.; Clausen, T.; Balducci, C. Antecedents of workplace bullying among employees in Germany: Five-Year lagged effects of job demands and job resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Tuckey, M.R.; McLinton, S.S.; Dollard, M.F. Prevention through job design: Identifying high-risk job characteristics associated with workplace bullying. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H. Job autonomy and workload as antecedents of workplace bullying: A two-wave test of Karasek’s Job Demand Control Model for targets and perpetrators. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czakert, J.P.; Berger, R. The indirect role of passive-avoidant and transformational leadership through job and team level stressors on workplace cyberbullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, C.B.; Keller, M.; Chilcutt, A.; Nelson, M.D. No laughing matter: Workplace bullying, humor orientation, and leadership styles. Workplace Health Saf. 2019, 67, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence Laschinger, H.K.; Wong, C.A.; Grau, A.L. The influence of authentic leadership on newly graduated nurses’ experiences of workplace bullying, burnout and retention outcomes: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence Laschinger, H.K.; Fida, R. New nurses burnout and workplace wellbeing: The influence of authentic leadership and psychological capital. Burn. Res. 2014, 1, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogstad, A.; Einarsen, S.; Torsheim, T.; Aasland, M.S.; Hetland, H. The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behavior. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoel, H.; Glasø, L.; Hetland, J.; Cooper, C.L.; Einarsen, S. Leadership styles as predictors of self-reported and observed workplace bullying. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.; O’Driscoll, M.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Roche, M.; Bentley, T.; Catley, B.; Teo, S.T.T.; Trenberth, L. Predictors of workplace bullying and cyber-bullying in New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Kang, J. Influencing factors and consequences of workplace bullying among nurses: A structural equation modeling. Asian Nurs. Res. 2018, 12, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågotnes, K.W.; Skogstad, A.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R.; Bakker, A.B.; Einarsen, S.V. Daily work pressure and exposure to bullying-related negative acts: The role of daily transformational and laissez-faire leadership. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M.R.; Li, Y.; Chen, P.Y. The role of transformational leadership in workplace bullying. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2017, 4, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.L.; Kulik, C.T. The devolution of HR to the line: Implications for perceptions of people management effectiveness. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.; Hutchinson, S. Front-line managers as agents in the HRM-performance causal chain: Theory, analysis and evidence. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2007, 17, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Takeuchi, R.; Lepak, D.P. Where do we go from here? New perspectives on the black box in strategic human resource management research. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 1448–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Flood, P.; Rousseau, D.; Morris, T. Line managers as paradox navigators in HRM implementation: Balancing consistency and individual responsiveness. J. Manag. 2018, 46, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, D.; Notelaers, G. Friend or foe? The impact of high-performance work practices on workplace bullying. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 30, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Noblet, A. Chapter Introduction: Organizational interventions: Where we are, where we go from here? In Organizational Interventions for Health and Well-Being; Nielsen, K., Noblet, A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.; Randall, R.; Holten, A.-L.; González, E.R. Conducting organizational-level occupational health interventions: What works? Work Stress 2010, 24, 234–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ind, N.; Coates, N. The meanings of co-creation. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Christensen, M. Positive participatory organizational interventions: A multilevel approach for creating healthy workplaces. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 696245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodbari, H.; Axtell, C.; Nielsen, K.; Sorensen, G. Organisational interventions to improve employees’ health and wellbeing: A realist synthesis. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 1058–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abildgaard, J.S.; Hasson, H.; von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Løvseth, L.T.; Ala-Laurinaho, A.; Nielsen, K. Forms of participation: The development and application of a conceptual model of participation in work environment interventions. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2020, 41, 746–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Nielsen, K.; Edwards, K.; Hasson, H.; Ipsen, C.; Savage, C.; Simonsen Abildgaard, J.; Richter, A.; Lornudd, C.; Mazzocato, P.; et al. How to design, implement and evaluate organizational interventions for maximum impact: The Sigtuna Principles. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 30, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, M. Co-design as a process of joint inquiry and imagination. Des. Issues 2013, 29, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.P.; Branch, S.; Caponecchia, C. Success factors in workplace bullying interventions. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020, 13, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; McGowan, M.W.; Turner, L.A. Grounded theory in practice: Is it inherently a mixed method? Res. Sch. 2010, 17, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, S.K. A longitudinal examination of how champions influence others to support their projects. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1998, 15, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notelaers, G.; Van der Heijden, B.; Hoel, H.; Einarsen, S. Measuring bullying at work with the short-negative acts questionnaire: Identification of targets and criterion validity. Work Stress 2019, 33, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Dormann, C.; Van Vegchel, N.; Von Nordheim, T.; Dollard, M.F.; Cotton, S.; Van den Tooren, M. The DISC Questionnaire English Version 2.0; Eindhoven University of Technology: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun Tie, Y.; Birks, M.; Francis, K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312118822927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Babchuk, W.A.; Smith, M.C.H.; Stevens, J. Contemporary approaches to mixed methods–grounded theory research: A field-based analysis. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2019, 13, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Randall, R. Opening the black box: Presenting a model for evaluating organizational-level interventions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.K.; Corley, K.G. Building better theory by bridging the quantitative–qualitative divide. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBreton, J.M.; Senter, J.L. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, D. Ways of explaining workplace bullying: A review of enabling, motivating and precipitating structures and processes in the work environment. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 1213–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention Phase | Evaluation Data Sources | |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Analysis | Qualitative Analysis (and Waves) | |

| Preparation | -- | -- |

| Diagnosis | Risk audit tool assessing people management practices Survey measures of job demands, job resources, and self-reported workplace bullying exposure | -- |

| Solutions | -- | -- |

| Implementation | -- | Notes from implementation check-in meetings with store (Wave 3) |

| Evaluation | Risk audit tool assessing people management practices Survey measures of job demands, job resources, and self-reported workplace bullying exposure Internal company complaints data regarding ER cases, grievances, and workplace bullying Internal company data on employee advocacy and customer satisfaction | Focus groups with store leaders and team members (Wave 1) Interviews with HR personnel who supported the intervention (Wave 2) |

| Store-Level | Department-Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC1 | rwg | ICC1 | rwg | |

| Time 1 | ||||

| People management practices | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.10 | 0.89 |

| Job demands | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.09 | 0.79 |

| Job resources | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 0.85 |

| Workplace bullying | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.03 | 0.85 |

| Time 2 | ||||

| People management practices | 0.15 | 0.74 | 0.09 | 0.88 |

| Job demands | 0.11 | 0.80 | 0.12 | 0.82 |

| Job resources | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.09 | 0.90 |

| Workplace bullying | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.92 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Store-level analysis | ||||||||||

| Time 1 | ||||||||||

| 1. People management practices | 6.63 | 0.66 | ||||||||

| 2. Bullying | 0.77 | 0.19 | −0.69 * | |||||||

| 3. Job demands | 3.19 | 0.26 | −0.67 * | 0.73 * | ||||||

| 4. Job resources | 3.21 | 0.17 | 0.91 ** | −0.86 * | −0.78 * | |||||

| Time 2 | ||||||||||

| 5. People management practices | 7.08 | 0.70 | 0.51 | −0.56 | 0.44 | −0.76 * | 0.63 | |||

| 6. Bullying | 0.52 | 0.22 | −0.37 | 0.53 | −0.41 | 0.74 * | −0.56 | −0.87 * | ||

| 7. Job demands | 2.95 | 0.34 | −0.06 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.63 | −0.17 | −0.82 * | 0.75 * | |

| 8. Job resources | 3.39 | 0.17 | 0.26 | −0.71 * | 0.43 | −0.52 | 0.52 | 0.76 * | −0.77 * | −0.52 |

| Department-level analysis | ||||||||||

| Time 1 | ||||||||||

| 1. People management practices | 6.57 | 0.90 | ||||||||

| 2. Bullying | 0.76 | 0.32 | −0.58 ** | |||||||

| 3. Job demands | 3.23 | 0.38 | −0.44 ** | 0.65 ** | ||||||

| 4. Job resources | 3.20 | 0.29 | 0.72 ** | −0.60 ** | −0.48 ** | |||||

| Time 2 | ||||||||||

| 6. People management practices | 7.17 | 0.91 | 0.36 * | −0.29 | 0.18 | −0.47 ** | 0.28 | |||

| 7. Bullying | 0.52 | 0.36 | −0.26 | 0.17 | −0.14 | 0.31 | −0.07 | −0.43 * | ||

| 8. Job demands | 3.01 | 0.44 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.28 | −0.09 | −0.51 ** | 0.58 ** | |

| 9. Job resources | 3.45 | 0.43 | 0.15 | −0.23 | 0.13 | -0.34 * | 0.22 | 0.46 ** | −0.32 | −0.14 |

| Job Demands (T2) | Job Resources (T2) | Workplace Bullying (T2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | |||

| Job demands (T1) | 0.07 (0.20) | ||

| Job resources (T1) | 0.13 (0.24) | ||

| Bullying (T1) | 0.14 (0.15) | ||

| Predictors | |||

| People management practices (T2) | −0.23 (0.08) ** | 0.21 (0.08) ** | |

| Job demands (T2) | 0.44 (0.11) ** | ||

| Job resources (T2) | −0.18 (0.11) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Tuckey, M.R.; Neall, A.M.; Rose, A.; Wilson, L. Changing the Underlying Conditions Relevant to Workplace Bullying through Organisational Redesign. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054373

Li Y, Tuckey MR, Neall AM, Rose A, Wilson L. Changing the Underlying Conditions Relevant to Workplace Bullying through Organisational Redesign. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054373

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yiqiong, Michelle R. Tuckey, Annabelle M. Neall, Alice Rose, and Lauren Wilson. 2023. "Changing the Underlying Conditions Relevant to Workplace Bullying through Organisational Redesign" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054373

APA StyleLi, Y., Tuckey, M. R., Neall, A. M., Rose, A., & Wilson, L. (2023). Changing the Underlying Conditions Relevant to Workplace Bullying through Organisational Redesign. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054373