The Perceptions and Use of Urban Neighborhood Parks Since the Outbreak of COVID-19: A Case Study in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

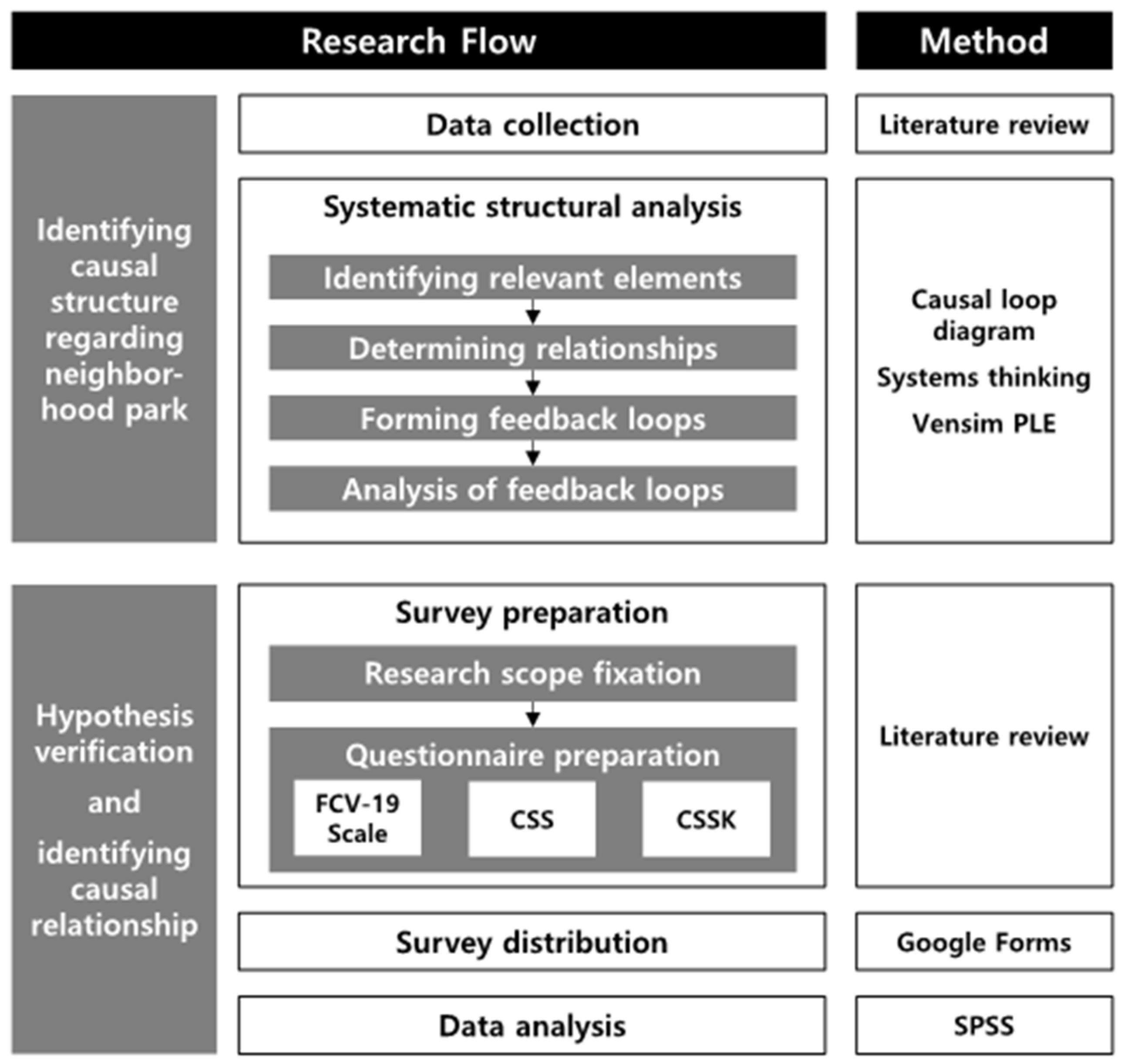

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Causal Structure of the Perception and Use of Urban Neighborhood Parks

2.1.1. Identifying Relevant Elements

2.1.2. Determining Relationships

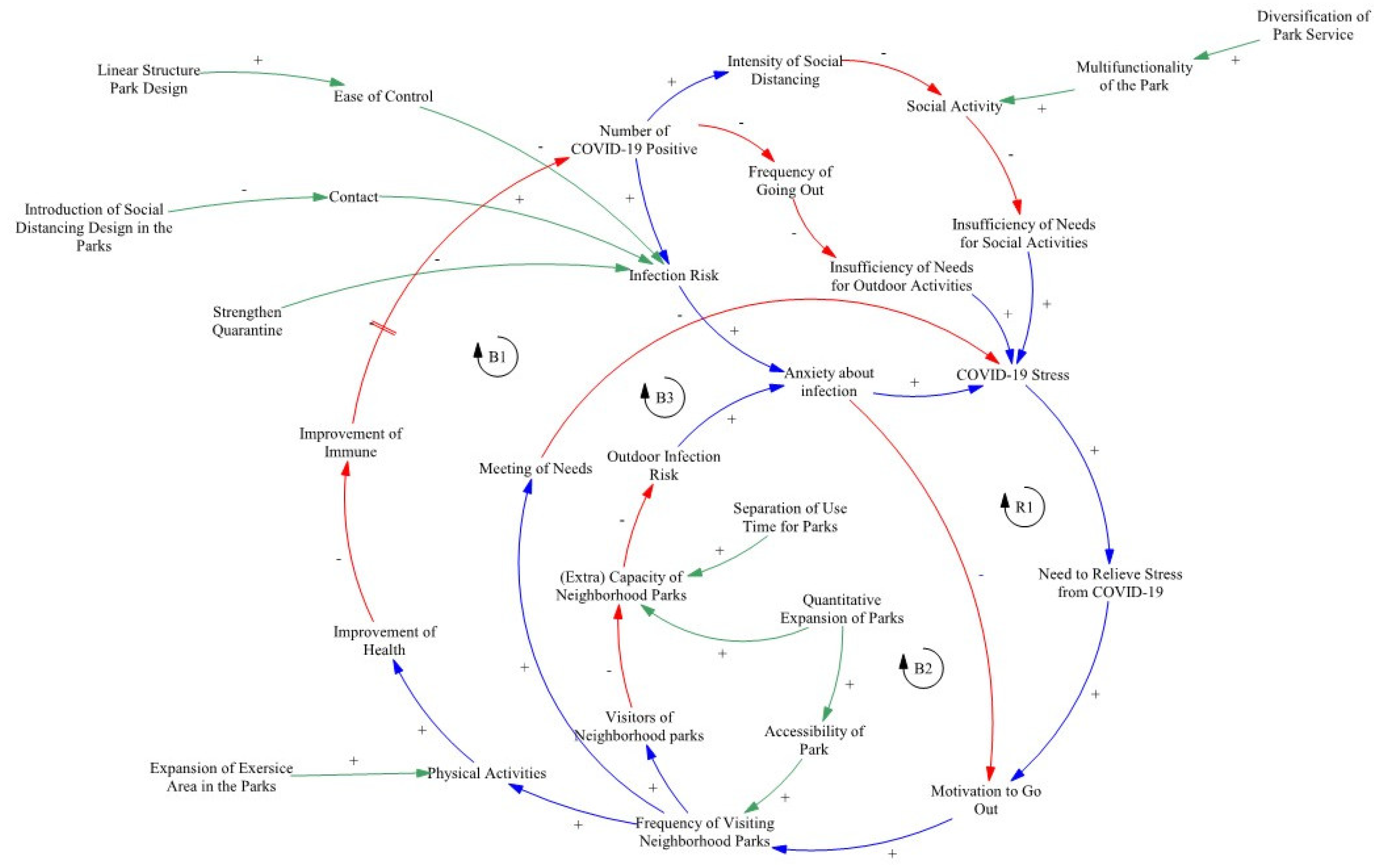

2.1.3. Forming Feedback Loops

2.1.4. Analysis of Feedback Loops

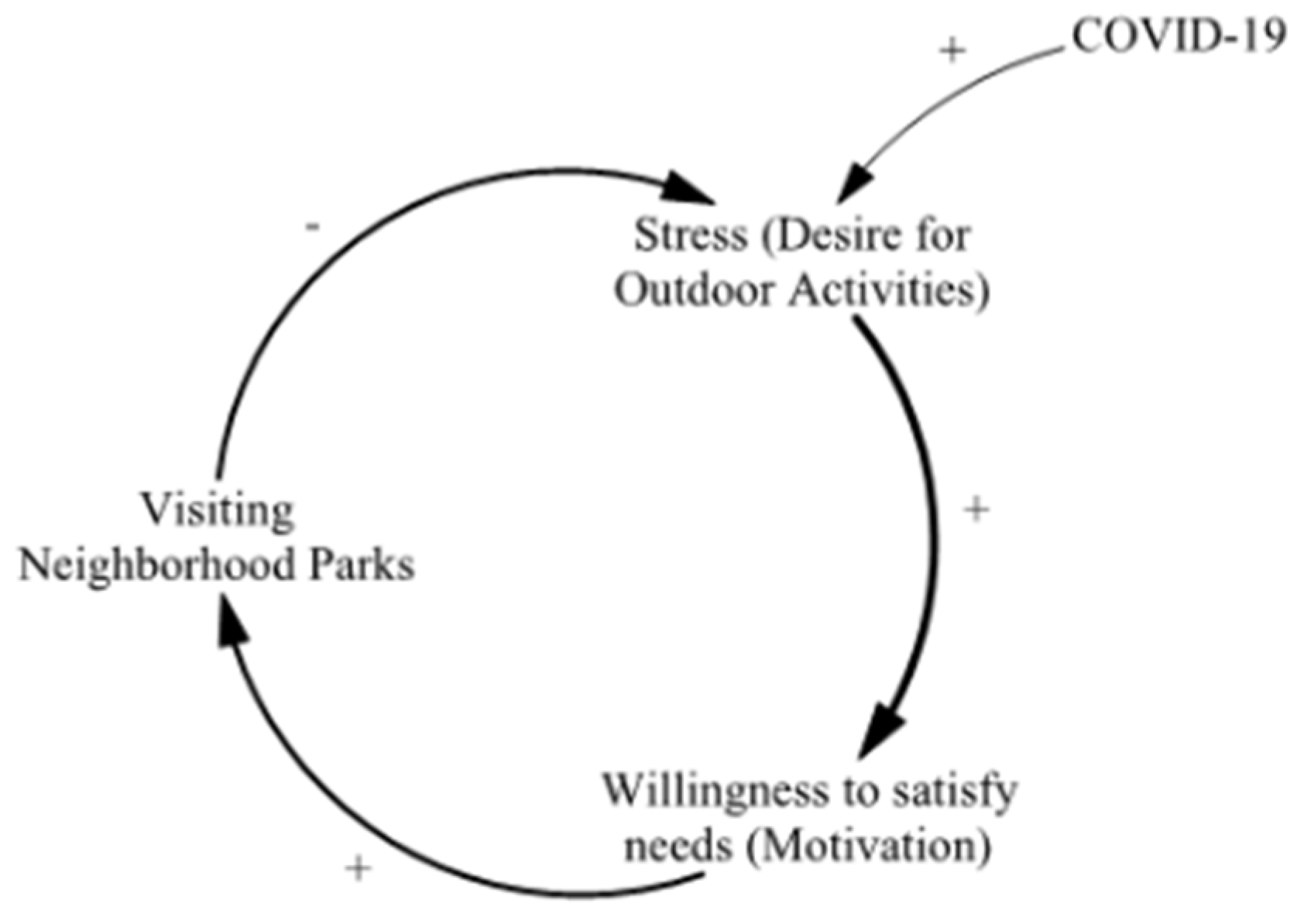

2.2. Causal Relationship between COVID-19 Stress, Motivation, and Frequency of Visits

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Questionnaire

2.2.3. Procedures

2.2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Causal Structure around Neighborhood Parks Based on the COVID-19 Response

3.2. Causal Relationship between COVID-19 Stress, the Motivation to Alleviate It, and Visits to Neighborhood Parks

3.2.1. General Characteristics of Respondents

3.2.2. Factor Analysis of COVID-19 Stress and Motivation for Visiting Neighborhood Parks

3.2.3. Effect of COVID-19 Stress on the Motivation to Visit Neighborhood Parks

3.2.4. Effect of Neighborhood Park Visit Motivation on Visit Frequency

4. Discussion

4.1. COVID-19 Stress and Motivation to Visit Parks

4.2. Park Visits as an Adaptive Behavior

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- COVID-19 Data Explorer—Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Shin, J.; Ki-Seok, J. The 7th Epidemic Begins… Vaccination Rate Is Very Low, so There Is Concern. Available online: https://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=148908276 (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- WHO|World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Panarese, P.; Azzarita, V. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Lifestyle: How Young People Have Adapted Their Leisure and Routine during Lockdown in Italy. Young 2021, 29, S35–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapaticci, S.; Neri, C.R.; Marseglia, G.L.; Staiano, A.; Chiarelli, F.; Verduci, E. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Lifestyle Behaviors in Children and Adolescents: An International Overview. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Mukoyama, A.; Naganawa, S.; Dan, I.; Husain, S.F.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R. Hemodynamic Response to Three Types of Urban Spaces before and after Lockdown during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, J.-Y.; Kim, J.W.; Myung, S.J.; Yoon, H.B.; Moon, S.H.; Ryu, H.; Yim, J.-J. Impact of COVID-19 on Lifestyle, Personal Attitudes, and Mental Health Among Korean Medical Students: Network Analysis of Associated Patterns. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 702092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.; Butcher, B. The Telegraph. How South Korea Can Teach the World to Live with COVID. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/science-and-disease/south-korea-can-teach-world-live-covid/ (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Choi, K.; Choi, H.; Kahng, B. COVID-19 Epidemic under the K-Quarantine Model: Network Approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 157, 111904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa, H.; Lee, W.; Lee, B. Corona Blue and Leisure Activities: Focusing on Korean Case. J. Internet Comput. Serv. 2021, 2, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli, P. Fear, Anxiety and Health-Related Consequences After the COVID-19 Epidemic. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H. 36.8% Complain of ‘Corona Blue’… Among the OECD, Korea Has the Highest 2021. Available online: https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/economy/economy_general/995688.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Seong, G.; Kim, S. The Impact of Changes in Daily Life Due to COVID-19 on Corona-Blue. J. Couns. Psychol. Educ. Welf. 2021, 5, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J.T. How City Parks Can Be Part of the COVID-19 Recovery—First Policy Response. Available online: https://policyresponse.ca/how-city-parks-can-be-part-of-the-covid-19-recovery/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Sung, H.; Kim, W.-R.; Oh, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, P.S.-H. Are All Urban Parks Robust to the COVID-19 Pandemic? Focusing on Type, Functionality, and Accessibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Bird, N.; Hallingberg, B.; Phillips, R.; Williams, D. The Role of Perceived Public and Private Green Space in Subjective Health and Wellbeing during and after the First Peak of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 211, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.K.; Svendsen, E.S.; Sonti, N.F.; Johnson, M.L. A Social Assessment of Urban Parkland: Analyzing Park Use and Meaning to Inform Management and Resilience Planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann-Wübbelt, A.; Fricke, A.; Sebesvari, Z.; Yakouchenkova, I.A.; Fröhlich, K.; Saha, S. High Public Appreciation for the Cultural Ecosystem Services of Urban and Peri-urban Forests during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Recreation and Park Association. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Parks and Recreation: Response and Recovery; National Recreation and Park Association: Ashburn, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maury-Mora, M.; Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; Varela-Martínez, C. Urban Green Spaces and Stress during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Case Study for the City of Madrid. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz-Santamaria, J.; Martinez-Cruz, A.L. Adaptive Governance of Urban Green Spaces across Latin America—Insights amid COVID-19. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Innes, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, G. Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on Urban Park Visitation: A Global Analysis. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A. How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact Urban Green Spaces? A Multi-Scale Assessment of Jeddah Megacity (Saudi Arabia). Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.-K.; Sparke, K. Self-Reported Well-Being and the Importance of Green Spaces—A Comparison of Garden Owners and Non-Garden Owners in Times of COVID-19. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 212, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W. Enhancing Systems-thinking Skills with Modelling. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2008, 39, 1099–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Hummelbrunner, R. Systems Concepts in Action; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Development and Initial Validation of the COVID Stress Scales. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 72, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Kim, E.; Park, S.; Lee, Y. Development and Initial Validation of the COVID Stress Scale for Korean People. Korea J. Couns. 2021, 22, 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, M.N.I.; Peng, Y.; Yiran, C.; Shouse, R.C. Disaster Resilience through Big Data: Way to Environmental Sustainability. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Warber, S.L.; Devine-Wright, P.; Gaston, K.J. Understanding Urban Green Space as a Health Resource: A Qualitative Comparison of Visit Motivation and Derived Effects among Park Users in Sheffield, UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebli, A.; Volgger, M.; Taplin, R. A Two-Dimensional Approach to Travel Motivation in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoh, K.-J.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, Y. A Study on Visitor Motivation and Satisfaction of Urban Open Space—In the Case of Waterfront Open Space in Seoul. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Arch. 2014, 42, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wei, W.; Zhao, B. Effects of Urban Parks on Residents’ Expressed Happiness before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 212, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.-L.; Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, M.J.; Han, H. Impact of Health Risk Perception on Avoidance of International Travel in the Wake of a Pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, J.S. Wisconsin State Parks and the COVID-19 Pandemic; UW Geography Undergraduate Colloquium; University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, E.P.; Freeman, P.; Gladwell, V.F. A Cross-Sectional Study Examining Predictors of Visit Frequency to Local Green Space and the Impact This Has on Physical Activity Levels. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.J.; Baxter-King, R.; Vavreck, L.; Naeim, A.; Wenger, N.; Sepucha, K.; Stanton, A.L. Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Large, Longitudinal, Cross-Sectional Survey. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e33585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. COVID Stress Syndrome: Concept, Structure, and Correlates. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, B.-H.; Hong, C.-Y. Does Risk Awareness of COVID-19 Affect Visits to National Parks? Analyzing the Tourist Decision-Making Process Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volenec, Z.M.; Abraham, J.O.; Becker, A.D.; Dobson, A.P. Public Parks and the Pandemic: How Park Usage Has Been Affected by COVID-19 Policies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F.; Wang, S.D.; Do, B.; Courtney, J. Early Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity Locations and Behaviors in Adults Living in the United States. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 20, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. Chosun Media. COVID-19 Risk Moved to the Park… Continued “Balloon Effect” 2020. Available online: https://health.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2020/09/07/2020090702992.html (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, E.; Kahn, P.H.; Chen, H.; Esperum, G. Relatively Wild Urban Parks Can Promote Human Resilience and Flourishing: A Case Study of Discovery Park, Seattle, Washington. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.T.H.; Lam, T.W.L.; Cheung, L.T.O.; Fok, L. Protected Areas as a Space for Pandemic Disease Adaptation: A Case of COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 207, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, I.; Harel, N.; Mishori, D. The Benefits of Discrete Visits in Urban Parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinde, B.; Patil, G.G. Biophilia: Does Visual Contact with Nature Impact on Health and Well-Being? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S. Environmental Psychology and Human Behavior—Eco-Friendly Environmental Design Research; Bomundang: North Chungcheong, Republic of Korea, 2007; ISBN 9788984131361. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Cho, S.; Kwon, O.; Yoo, Y.; Choi, G. Strategies for Improving Neighborhood Parks and Green Spaces for the Post-COVID-19 Era; AURI: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, E.; Park, J.; Lee, C.; Hong, N. Planning Model of Urban Green Infrastructure in the Post-COVID19 Era; KRIHS: Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.L. COVID-19, Green Space Usage Rate Is Increasing... Programs Tailored to the Characteristics of Each Space Must Be Developed. Available online: https://www.lafent.com/mbweb/news/view.html?news_id=129556&mcd=A01&kwda=%EB%85%B9%EC%A7%80%EA%B3%B5%EA%B0%84 (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Pintos, P. Seoul City Architectural Ideas Competition: Preparing for the Post COVID-19 Era; ArchDaily: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, J. The Trail Research Hub. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Changing Landscape of Trails 2022. Available online: https://www.trailresearchhub.com/post/the-covid-19-pandemic-and-the-changing-landscape-of-trails (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Graham, C. One-Way Trails: Why Have Them? Available online: https://news.openspaceauthority.org/blog/one-way-trails (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Lee, H.J.; Park, S.-Y. Environmental Orientation in Going Green: A Qualitative Approach to Consumer Psychology and Sociocultural Factors of Green Consumption. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2013, 23, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Mehmetoglu, M.; Vistad, O.I.; Andersen, O. Linking Visitor Motivation with Attitude towards Management Restrictions on Use in a National Park. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 9, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Scale | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Stress | Fear | [27,29,30] |

| Lethargy | [29] | |

| Anger | [29] | |

| Traumatic reaction | [30] | |

| Motivation of visit | Physical activity | [31,32] |

| Natural elements | [31,33] | |

| Stress relief | [31,32,33] | |

| Mental activity | [31,32,33] | |

| Social connection | [31,33] | |

| Related to COVID-19 | [32,34,35,36] | |

| Frequency of visits | . | [37] |

| Feedback Loop | Property | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| B1 | Balancing | Stress arises when the desire to engage in various activities is not satisfied due to the spread of COVID-19. To solve this problem, motivation to go out occurs, which leads to a visit to the neighborhood park. When needs are satisfied through a visit to the park, COVID-19 stress is reduced, forming feedback in which stress is balanced. |

| B2 | Balancing | As the number of COVID cases increases, people worry more about infection and are more willing to stay inside rather than go out and engage in contact with others. This may lead people to stay home and thus improve the pandemic conditions; however, it does not initially improve COVID-19 stress. |

| B3 | Balancing | Individuals visit neighborhood parks to relieve stress. By performing physical activities in the park, their health is improved and their immunity to COVID-19 increases. In the long term, this serves to prevent infection, forming a balancing loop in which the number of positive COVID-19 cases decreases. |

| R1 | Reinforcing | If many people become concentrated in a neighborhood park of limited capacity due to the motivation to go out stemming from COVID-19 stress, then the risk of outdoor infection increases. This increases concerns about infection, forming reinforcing feedback that increases COVID-19 stress. |

| Variable | Polarity | Variable | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of COVID-19 Positive cases | + | COVID-19 Stress | [28,39] |

| COVID-19 Stress | + | Motivation to go out | [40] |

| Frequency of Visiting Neighborhood Parks | + | Meeting of Needs | [41] |

| Frequency of Visiting Neighborhood Parks | + | Physical Activities | [42] |

| Capacity of Neighborhood Parks | − | Outdoor Infection Risk | [43] |

| Characteristics | Variables | Frequency | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 23 | 23.5 |

| Female | 75 | 76.5 | |

| Age | 10s | 6 | 6.1 |

| 20s | 49 | 50.0 | |

| 30s | 13 | 13.3 | |

| 40s | 18 | 18.4 | |

| 50s | 9 | 9.2 | |

| Over 60 | 3 | 3.1 | |

| Distance to neighborhood park (on foot) | Within 5 min | 34 | 34.7 |

| Within 10 min | 38 | 38.8 | |

| Within 30 min | 19 | 19.4 | |

| Over 30 min | 7 | 7.1 |

| Division | Communality | Factor Loading | M (SD) | EV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Item | |||||

| Factor 1 | Anxiety about infection (α = 0.885) | I am worried about getting infected with COVID-19. | 0.804 | 0.857 | 5.14 (1.506) | 6.889 |

| I am worried about when and where I will be infected with COVID-19. | 0.755 | 0.821 | 4.98 (1.586) | |||

| I’m worried that I might get infected with COVID-19 if I touch a handle in a public place. | 0.620 | 0.756 | 4.57 (1.693) | |||

| I’m worried about getting infected with COVID-19 because of people around me. | 0.656 | 0.740 | 5.03 (1.502) | |||

| I am worried about getting infected with COVID-19 in an enclosed place that I use frequently (e.g., elevators, public transportation). | 0.631 | 0.690 | 4.80 (1.705) | |||

| Factor 2 | Helplessness due to social disconnection (α = 0.849) | I am depressed because I cannot do hobbies or cultural activities as I did before because of COVID-19. | 0.726 | 0.827 | 4.88 (1.778) | 2.404 |

| As social distancing continues for a long time, I feel disconnected from society. | 0.725 | 0.816 | 4.19 (1.919) | |||

| Due to COVID-19, more time at home has lowered my will to live and made me lethargic. | 0.752 | 0.722 | 4.17 (1.969) | |||

| It is hard to see family and friends very often because of COVID-19. | 0.656 | 0.699 | 4.83 (1.811) | |||

| Factor 3 | Anger over contagion (α = 0.779) | I get angry when I see people going to high-risk facilities (e.g., pubs, clubs) where there is a risk of spreading COVID-19. | 0.772 | 0.854 | 5.37 (1.778) | 2.161 |

| I get angry at my boss, seniors, and adults in my family for forcing me to a dinner or meeting without considering the possibility of COVID-19 transmission. | 0.646 | 0.768 | 5.13 (1.848) | |||

| I follow the quarantine rules well, but I get angry when other people do not follow them properly. | 0.674 | 0.747 | 5.17 (1.687) | |||

| I get angry at religious people who insist on engaging in contact activities. | 0.559 | 0.602 | 5.81 (1.564) | |||

| Factor 4 | Traumatic reaction (α = 0.756) | When I think of COVID-19, I sweat or my heart beats quickly. | 0.767 | 0.851 | 1.40 (0.770) | 1.762 |

| I have been contemplating suicide because of COVID-19 stress. | 0.718 | 0.838 | 1.18 (0.615) | |||

| It is hard to concentrate because I’m worried about COVID-19. | 0.703 | 0.725 | 1.83 (1.149) | |||

| It is difficult to get enough sleep due to the psychological pressure of COVID-19. | 0.504 | 0.610 | 1.96 (1.235) | |||

| Factor 5 | Daily stress (α = 0.797) | Daily life has become terrifying due to COVID-19. | 0.771 | 0.703 | 4.17 (1.675) | 1.118 |

| When COVID-19 news is updated on TV or social media, it is stressful. | 0.689 | 0.700 | 4.31 (1.796) | |||

| Division | Communality | Factor Loading | M (SD) | EV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Item | |||||

| Factor 1 | Biophilia (α = 0.879) | To enjoy the beautiful scenery | 0.827 | 0.840 | 4.41 (1.931) | 4.012 |

| To rest | 0.722 | 0.835 | 5.21 (1.778) | |||

| To experience nature | 0.756 | 0.811 | 4.47 (1.933) | |||

| For psychological stability and relaxation | 0.717 | 0.751 | 5.26 (1.575) | |||

| To energize | 0.642 | 0.655 | 5.49 (1.372) | |||

| A visit to the park relieves tension | 0.572 | 0.593 | 4.03 (2.023) | |||

| Factor 2 | Exercise for health improvement (α = 0.645) | Because you can go for a walk or jog | 0.735 | 0.744 | 5.84 (1.249) | 2.013 |

| To exercise in the park | 0.643 | 0.731 | 4.54 (1.742) | |||

| Because you can breathe the fresh air | 0.603 | 0.514 | 5.18 (1.719) | |||

| To prevent disease through healthy living | 0.677 | 0.484 | 3.67 (2.014) | |||

| Factor 3 | Social and leisure activities (α = 0.616) | To meet new people | 0.662 | 0.804 | 1.73 (1.273) | 1.952 |

| To read a book in the park | 0.598 | 0.708 | 1.95 (1.424) | |||

| Factor 4 | Safety from infection in the park (α = 0.699) | Because the park is safer from COVID-19 than other places | 0.826 | 0.892 | 4.45 (1.873) | 1.911 |

| Because the park is sanitary | 0.671 | 0.658 | 3.30 (1.682) | |||

| Factor 5 | Meeting the desire to go out (α = 0.797) | To satisfy the desire to go out | 0.816 | 0.873 | 4.44 (1.959) | 1.837 |

| To get out of the house | 0.790 | 0.827 | 4.51 (1.922) | |||

| Factor 6 | Alternative place exploration (α = 0.623) | To meet friends | 0.724 | 0.773 | 3.50 (2.112) | 1.584 |

| No limit on the number of people | 0.736 | 0.645 | 3.41 (2.004) | |||

| More free time because daily life has shifted to working at home or online | 0.591 | 0.509 | 3.14 (1.948) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Chon, J.; Park, Y.; Lee, J. The Perceptions and Use of Urban Neighborhood Parks Since the Outbreak of COVID-19: A Case Study in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054259

Lee J, Chon J, Park Y, Lee J. The Perceptions and Use of Urban Neighborhood Parks Since the Outbreak of COVID-19: A Case Study in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054259

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jiku, Jinhyung Chon, Yujin Park, and Junga Lee. 2023. "The Perceptions and Use of Urban Neighborhood Parks Since the Outbreak of COVID-19: A Case Study in South Korea" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054259

APA StyleLee, J., Chon, J., Park, Y., & Lee, J. (2023). The Perceptions and Use of Urban Neighborhood Parks Since the Outbreak of COVID-19: A Case Study in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054259