Enjoyed by Jack but Endured by Jill: An Exploratory Case Study Examining Differences in Adolescent Design Preferences and Perceived Impacts of a Secondary Schoolyard

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Do differences exist in student perceptions of schoolyard attractiveness based on student year level and gender?

- Do differences exist in student perceptions of schoolyard restorative quality based on student year level and gender?

2. Materials and Methods

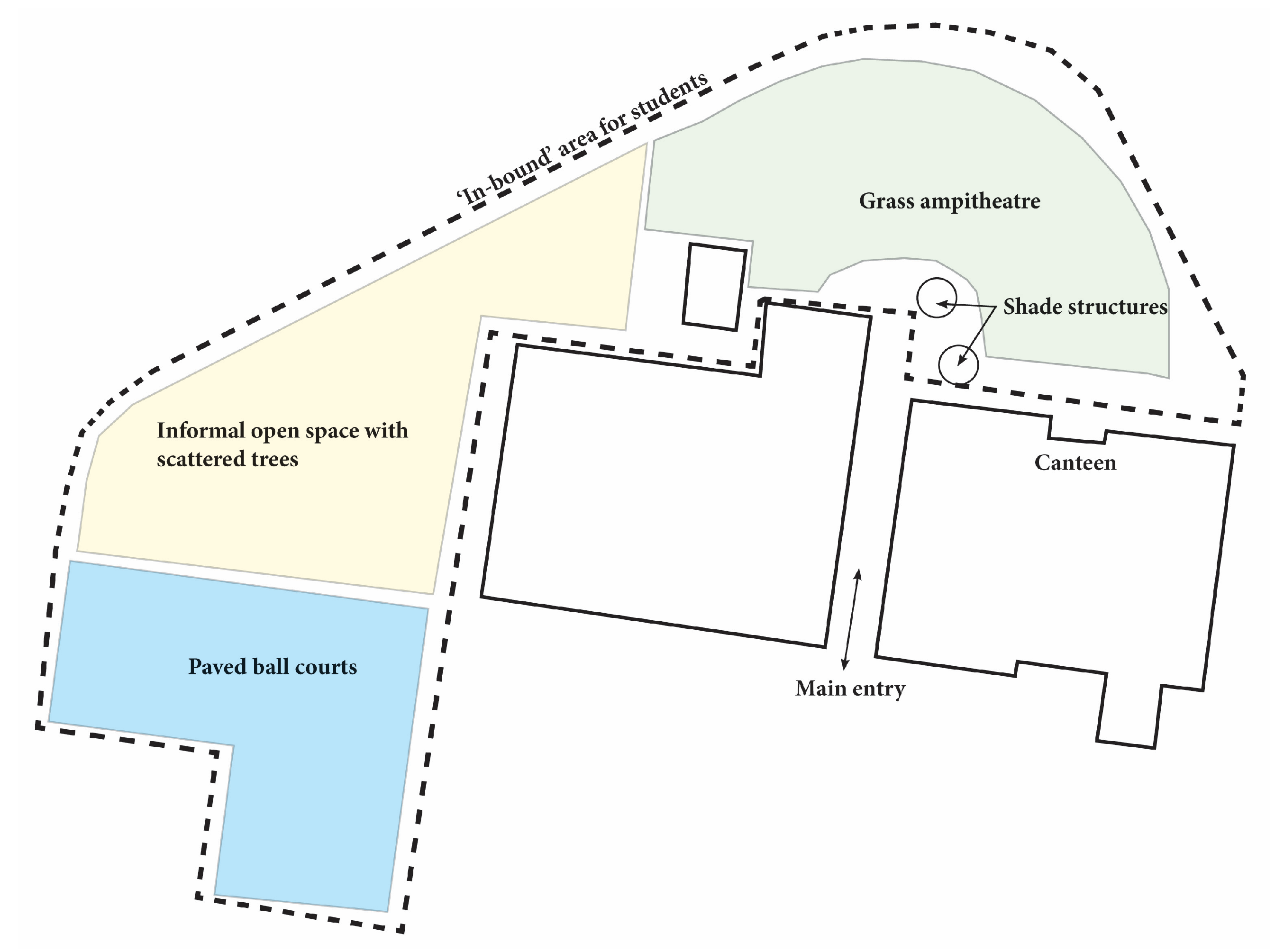

2.1. Site Context

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Survey Instrument: Schoolyard Attractiveness

2.2.2. Survey Instrument: Schoolyard Restorative Quality

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

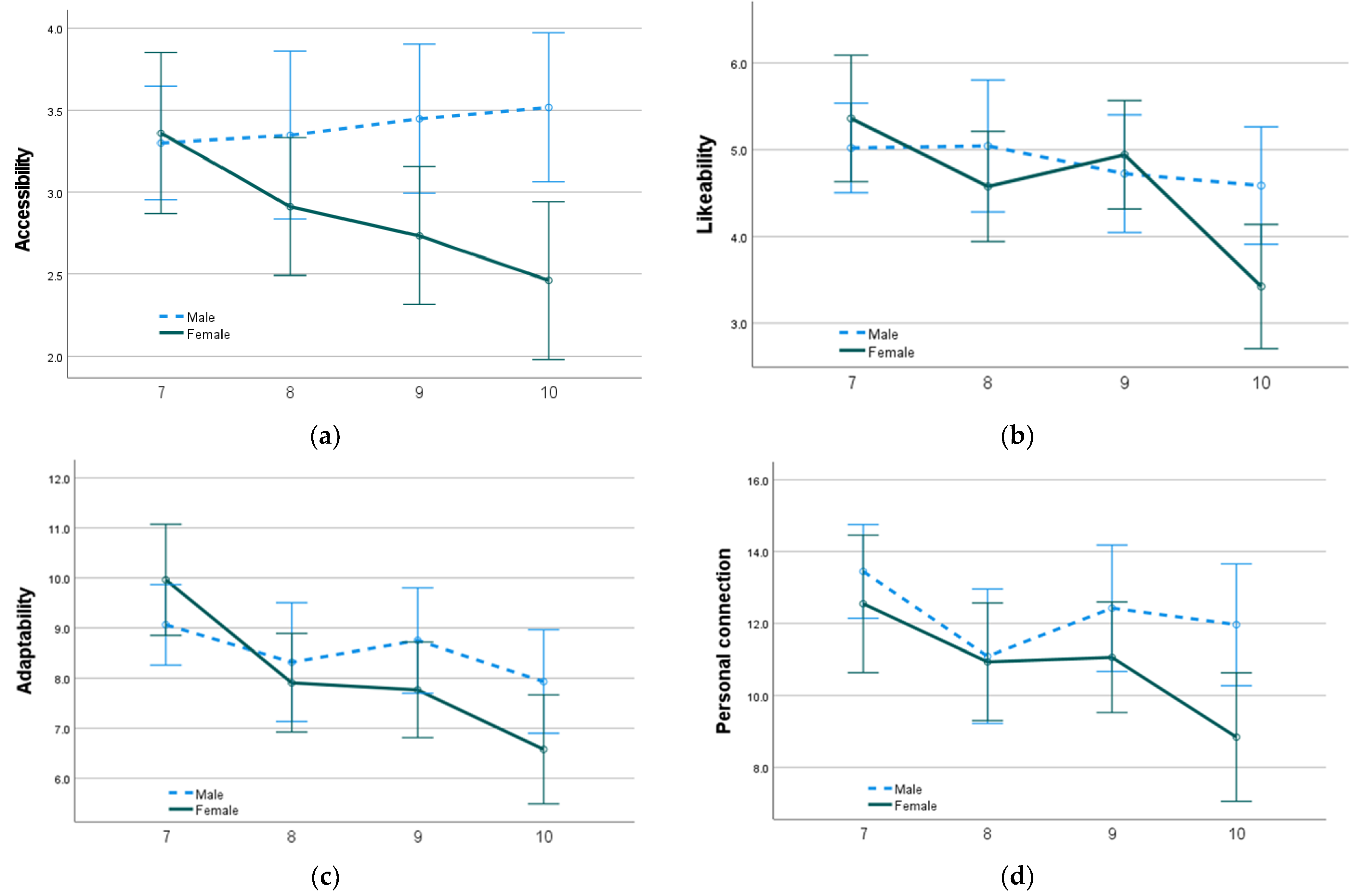

3.1. Significance of Student Year Level and Gender on Perceptions of Schoolyard Attractiveness

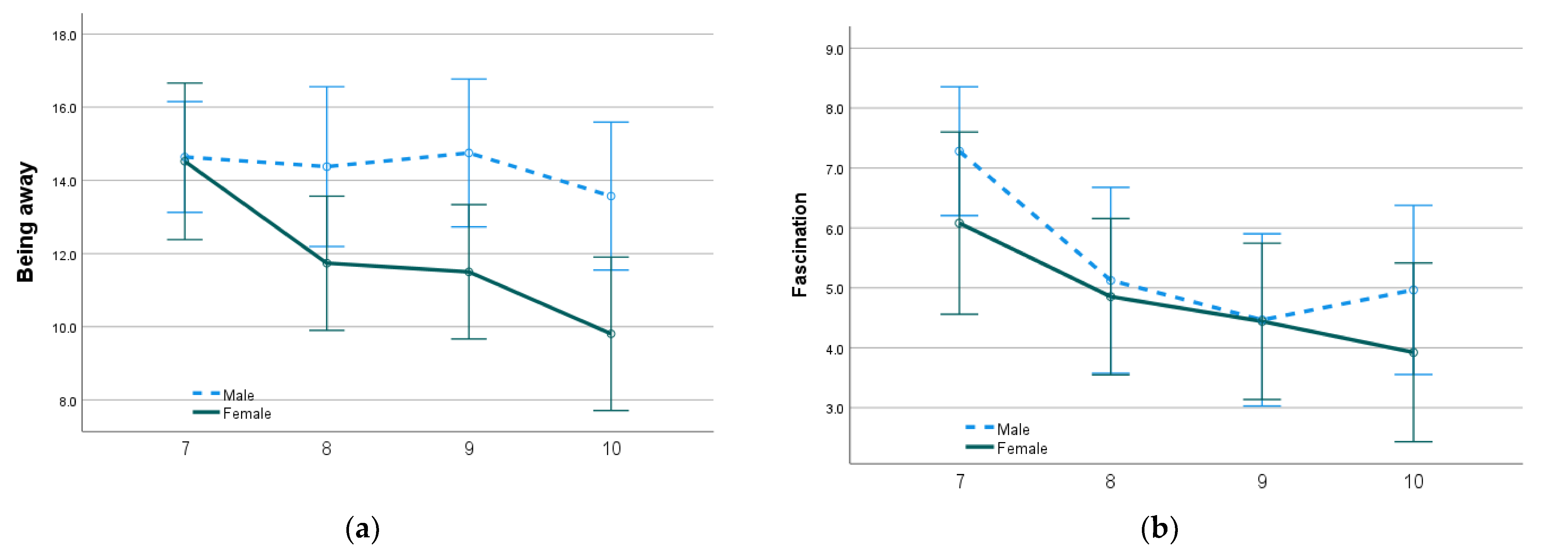

3.2. Significance of Student Year Level and Gender on Perceptions of Schoolyard Restorative Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray, P. The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Am. J. Play. 2011, 3, 443–463. [Google Scholar]

- Blatchford, P.; Baines, E.; Pellegrini, A. The social context of school playground games: Sex and ethnic differences, and changes over time after entry to junior school. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 21, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.C.; Dyment, J.E. Grounds for health: The intersection of green school grounds and health-promoting schools. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippman, P.C. Evidence-Based Design of Elementary and Secondary Schools: A Responsive Approach to Creating Learning Environments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, B. A qualitative investigation of Australian youth perceptions to enhance school physical activity: The Environmental Perceptions Investigation of Children’s Physical Activity (EPIC-PA) study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.M.; Cohen, D.A.; Evenson, K.R.; Elder, J.; Catellier, D.; Ashwood, J.S.; Overton, A. Weekend schoolyard accessibility, physical activity, and obesity: The Trial of Activity in Adolescent Girls (TAAG) study. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samborski, S. Biodiverse or barren school grounds: Their effects on children. Child. Youth Environ. 2010, 20, 67–115. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C.; Tranter, P. Children and Their Urban Environment: Changing Worlds; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. Negotiating between children and adult design values in open space projects. Des. Stud. 1988, 9, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkauskaite, R.; Gisladottir, T.; Pihu, M.; Kjonniksen, L.; Lounassalo, I.; Huovinen, T.; Gruodyte-Raciene, R.; Visagurskiene, K.; Olafson, O.; Kull, M.; et al. Schoolyard Affordances for Physical Activity: A Pilot Study in 6 Nordic–Baltic Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.; Fildes, J.; Perrens, B.; Plummer, J.; Carlisle, E.; Cockayne, N.; Werner-Seidler, A. Can We Talk? 2019. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/264826 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Bernard, M.E.; Stephanou, A. Ecological levels of social and emotional wellbeing of young people. Child Indic. Res. 2018, 11, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttazzoni, A.; Dean, J.; Minaker, L. Urban design and adolescent mental health: A qualitative examination of adolescent emotional responses to pedestrian- and transit-oriented design and cognitive architecture concepts. Health Place 2022, 76, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, M.; Abdulah, M.; Eriksson, A. Secondary school students’ perspectives and use of three school grounds of varying size, content and design. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthamatten, P.; Brink, L.; Lampe, S.; Greenwood, E.; Kingston, B.; Nigg, C. An assessment of schoolyard renovation strategies to encourage children’s physical activity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlowski, C.S.; Andersen, H.B.; Troelsen, J.; Schipperijn, J. Children’s physical activity behavior during school recess: A pilot study using GPS, accelerometer, participant observation, and go-along interview. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Salmon, J.; Parrish, A.-M.; Stanley, R.M.; Okely, A.D. Physical activity during school recess: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willenberg, L.J.; Ashbolt, R.; Holland, D.; Gibbs, L.; MacDougall, C.; Garrard, J.; Green, J.B.; Waters, E. Increasing school playground physical activity: A mixed methods study combining environmental measures and children’s perspectives. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, C.S.; Ergler, C.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T.; Schipperijn, J.; Troelsen, J. ‘Like a soccer camp for boys’ A qualitative exploration of gendered activity patterns in children’s self-organized play during school recess. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spark, C.; Porter, L.; de Kleyn, L. ‘We’re not very good at soccer’: Gender, space and competence in a Victorian primary school. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, M.A.; Daniel, E.; Jack, N. Impact of urban schoolyard play zone diversity and nature-based design features on unstructured recess play behaviors. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2023, 230, 104632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagot, K.L.; Allen, F.C.L.; Toukhsati, S. Perceived restorativeness of children’s school playground environments: Nature, playground features and play period experiences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, Z.A.; Macmillan, S. The valuation of intangibles: Explored through primary school design. In Proceedings of the CIB W096 Architectural Management, Special Meeting on Designing Value: New Directions in Architectural Management, Lyngby, Denmark, 2–4 November 2005; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J. Measuring value or only cost: The need for new valuation methods. In Designing Better Buildings; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, S.; Hall, E.; Wall, K.; Woolner, P.; McCaughey, C. The Impact of School Environments: A Literature Review; University of Newcastle: Callaghan, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz, A.; Derr, V.; Chawla, L. Fluid or fixed? Processes that facilitate or constrain a sense of inclusion in participatory schoolyard and park design. Landsc. J. 2018, 37, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadh, O. Sustainability and green building rating systems: LEED, BREEAM, GSAS and Estidama critical analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 11, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R. The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkarim, D.; Nasar, J.L. Are livable elements also restorative? J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.; Gobster, P.H. Shades of green: Measuring the ecology of Urban green space in the context of human health and well-being. Nat. Cult. 2010, 5, 338–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A.E.; Hartig, T.; Staats, H. Preference for nature in urbanized societies: Stress, restoration, and the pursuit of sustainability. J. Soc. Iss. 2007, 63, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Wilson, E.R. Evaluating restoration in urban green spaces: Does setting type make a difference? Landsc. Urban Plann. 2014, 127, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, M.D.M.D. The link between landscape preferences and perceived restorativeness—Current research trends and suggestions for future studies. In Environmental Psychology: New Developments; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Cohen, D.A. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: A conceptual model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.J. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Keena, K.; Pevec, I.; Stanley, E. Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place 2014, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk-Wesselius, J.; Maas, J.; Hovinga, D.; Van Vugt, M.; Van den Berg, A. The impact of greening schoolyards on the appreciation, and physical, cognitive and social-emotional well-being of schoolchildren: A prospective intervention study. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2018, 180, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathleen, L.B.; Frances, E.K.; Felicity, C.L.A. Amendments to the Perceived Restorative Components Scale for Children (PRCS-C II). Child. Youth Environ. 2007, 17, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bowler, P.A. Further Development of a Measure of Perceived Environmental Restorativeness; Working Paper No. 5; Institutet för Bostads-och Urbanforskning: Gävle, Sweden, 1997; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The urban forest as a source of psychological well-being. In Urban Forest Landscapes: Integrating Multidisciplinary Perspectives; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1995; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Joliffe, I.T.; Morgan, B. Principal component analysis and exploratory factor analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1992, 1, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Discarding variables in a principal component analysis. I: Artificial data. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 1972, 21, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, E.; Torsheim, T.; Sallis, J.F.; Samdal, O. The characteristics of the outdoor school environment associated with physical activity. Health Educ. Res. 2008, 25, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.W.; Pender, N.J.; Antonakos, C.L.; Ronis, D.L. Changes in physical activity beliefs and behaviors of boys and girls across the transition to junior high school. J. Adolesc. Health 1998, 22, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, R.M.; Boshoff, K.; Dollman, J. Voices in the playground: A qualitative exploration of the barriers and facilitators of lunchtime play. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, A.C. The impact of playground design on the play behaviors of children with differing levels of physical competence. Early Child. Res. Q. 1999, 14, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, P.E. Natural landscapes, gathering places, and prospect refuges: Characteristics of outdoor places valued by teens. Child. Environ. Q. 1988, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K. Refuge and imagination: Places of peace in childhood. Child. Environ. Q. 1990, 7, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, D. Children’s Special Places: Exploring the Role of Forts, Dens, and Bush Houses in Middle Childhood; Wayne State University Press: Detriot, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.; Hartig, T. Restorative qualities of favorite places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Kyttä, M.; Hartig, T. Restorative experience, self-regulation, and children’s place preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högman, J.; Augustsson, C.; Hedström, P. Let’s do those 60 minutes! Children’s perceived landscape for daily physical activity. Sport Educ. Soc. 2020, 25, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, E.; MacPhail, A.; Enright, E. Physical activity experiences of young people in an area of disadvantage: ‘There’s nothing there for big kids, like us’. Sport Educ. Soc. 2016, 21, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjørtoft, I. Landscape as playscape: The effects of natural environments on children’s play and motor development. Child. Youth Environ. 2004, 14, 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, M.; Gunnarsson, A.; Mårtensson, F.; Andersson, S. Children’s perspectives on vegetation establishment: Implications for school ground greening. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagels, P.; Raustorp, A.; De Leon, A.P.; Mårtensson, F.; Kylin, M.; Boldemann, C. A repeated measurement study investigating the impact of school outdoor environment upon physical activity across ages and seasons in Swedish second, fifth and eighth graders. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, M.A.; Hendry, C.F.; Yee, S.A. Physical Activity and Social Behaviors of Urban Children in Green Playgrounds. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, H.B.; Klinker, C.D.; Toftager, M.; Pawlowski, C.S.; Schipperijn, J. Objectively measured differences in physical activity in five types of schoolyard area. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2015, 134, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beighle, A.; Morgan, C.F.; Le Masurier, G.; Pangrazi, R.P. Children’s physical activity during recess and outside of school. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L. Outdoor Spaces–Jungle or Exercise Yard? A Study of Facilities, Children and Physical Activity at School; Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research (NIBR): Oslo, Norway, 2004; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Dyment, J.E.; Bell, A.C.; Lucas, A.J. The relationship between school ground design and intensity of physical activity. Child. Geogr. 2009, 7, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.J.; Fairclough, S.J.; Ridgers, N.D.; Porteous, C. An observational assessment of physical activity levels and social behaviour during elementary school recess. Health Educ. J. 2013, 72, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paechter, C.; Clark, S. Learning gender in primary school playgrounds: Findings from the Tomboy Identities Study. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2007, 15, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, C.S.; Andersen, H.B.; Arvidsen, J.; Schipperijn, J. Changing recess geographies: Children’s perceptions of a schoolyard renovation project promoting physical activity. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.J.; Dyment, J.E. Where do children choose to play on the school ground? The influence of green design. Education 3-13 2010, 38, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, F. Children’s organized sports: A developmental perspective. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2004, 75, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Szczytko, R.; Bowers, E.P.; Stephens, L.E.; Stevenson, K.T.; Floyd, M.F. Outdoor Time, Screen Time, and Connection to Nature: Troubling Trends Among Rural Youth? Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 966–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, O.L.K.; Bann, D.; Patalay, P. The gender gap in adolescent mental health: A cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM—Popul. Health 2021, 13, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillman, D.; Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.; McAnirlin, O. Do sex and gender modify the association between green space and physical health? A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Survey Questions |

|---|---|

| Personal connection | The design of this schoolyard encouraged me to be adventurous |

| The design of this schoolyard provides a sense of belonging | |

| The design of this schoolyard is engaging | |

| The design of this schoolyard promotes well-being | |

| The design of this schoolyard is liberating | |

| Design adaptability | The design of this schoolyard is diverse |

| The design of this schoolyard provides age-appropriate play | |

| The design of this schoolyard promotes physical activity | |

| Likeability | Please rate your opinion of the schoolyard with one being the worst and ten being the best |

| Accessibility | The design of this schoolyard is accessible by all |

| Fascination | There are lots of interesting places in the school ground |

| There are lots of things to discover in the school ground | |

| There are lots of interesting things to look at in the school ground | |

| There are many things in the school ground that I find fascinating | |

| Being away | When I am in the school ground, it feels as though I am in different surroundings than when I am in the classroom |

| When I am in the school ground, it feels as though I am in a different place than in the classroom | |

| When I am in the school ground, I do different things than in the classroom | |

| When I am in the school ground, I feel free from all the things teachers want me to do | |

| When I am in the school ground, I feel free from schoolwork and class time | |

| When I am in the school ground, I am away from things I must do | |

| Compatibility | The things I like to do can be done in the school ground |

| The things I want to do can be done in the school ground | |

| Extent | I can do many different things in one part of the school ground |

| I can think of all the different areas of the school ground as like lots of little school grounds joined together | |

| I do different things in different areas of the school ground |

| Year Level | Males | Females | Total Students | % Total Students | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % Year | Total | % Year | |||

| 7 | 50 | 66.7% | 25 | 33.3% | 75 | 29.8% |

| 8 | 25 | 42.4% | 34 | 57.6% | 59 | 23.4% |

| 9 | 29 | 46.0% | 34 | 54.0% | 63 | 25.0% |

| 10 | 29 | 52.7% | 26 | 47.3% | 55 | 21.8% |

| Total | 133 | 119 | 252 | 100.0% | ||

| Survey Measure | Year 7 | Year 8 | Year 9 | Year 10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Attractiveness | ||||||||

| Likeability | 5.14 ± 2.07 | 5.18 ± 1.99 | 5.00 ± 1.35 | 4.68 ± 1.79 | 4.77 ± 1.82 | 4.94 ± 2.03 | 4.46 ± 1.50 | 3.40 ± 1.87 |

| Accessibility | 3.42 ± 1.37 | 3.36 ± 1.40 | 3.36 ± 0.95 | 2.82 ± 1.21 | 3.54 ± 1.14 | 2.74 ± 1.29 | 3.38 ± 1.30 | 2.52 ± 1.16 |

| Adaptability | 9.23 ± 3.22 | 9.91 ± 2.79 | 8.31 ± 2.10 | 7.89 ± 3.18 | 8.77 ± 2.66 | 7.76 ± 3.06 | 7.77 ± 2.70 | 6.48 ± 2.65 |

| Personal Connection | 13.63 ± 5.01 | 12.55 ± 4.94 | 10.86 ± 4.02 | 11.36 ± 4.73 | 12.42 ± 4.57 | 11.06 ± 4.53 | 11.73 ± 4.50 | 8.84 ± 3.47 |

| Restorative quality | ||||||||

| Being away | 15.00 ± 6.01 | 14.05 ± 5.95 | 14.23 ± 4.45 | 12.04 ± 6.22 | 14.62 ± 5.04 | 11.5 ± 5.00 | 13.46 ± 5.41 | 9.92 ± 5.57 |

| Fascination | 7.19 ± 4.77 | 5.27 ± 3.61 | 5.27 ± 3.45 | 5.11 ± 3.56 | 4.46 ± 3.75 | 4.44 ± 3.96 | 4.92 ± 3.59 | 4.00 ± 3.38 |

| Compatibility | 3.74 ± 2.56 | 4.00 ± 2.02 | 3.55 ± 1.95 | 2.89 ± 1.91 | 3.42 ± 2.32 | 3.38 ± 2.34 | 3.42 ± 2.23 | 2.72 ± 2.13 |

| (Extent) | 6.00 ± 3.16 | 5.55 ± 3.00 | 5.45 ± 2.41 | 4.80 ± 2.66 | 5.27 ± 3.04 | 4.97 ± 2.81 | 5.23 ± 2.89 | 4.00 ± 3.11 |

| Likeability | Accessibility | Design Adaptability | Personal Connection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | |

| Gender (male) | 1.16 * | 0.18 to 2.15 | 1.06 ** | 0.40 to 1.72 | 1.35 | −0.15 to 2.86 | 3.12 * | 0.66 to 5.59 |

| Year 7 (total) | 1.94 *** | 0.92 to 2.96 | 0.9 ** | 0.21 to 1.58 | 3.38 *** | 1.83 to 4.94 | 3.71 ** | 1.09 to 6.33 |

| Year 7 males | −1.5 * | −2.83 to −0.17 | −1.12 * | −2.01 to −0.22 | −2.25 * | −4.29 to −0.22 | −2.22 | −5.61 to 1.16 |

| Year 8 (total) | 1.15 * | 0.20 to 2.11 | 0.45 | −0.19 to 1.09 | 1.33 | -0.14 to 2.80 | 2.09 | −0.33 to 4.52 |

| Year 8 males | −0.7 | −2.10 to 0.70 | −0.62 | −1.55 to 0.32 | −0.94 | -3.09 to 1.21 | −2.97 | −6.47 to 0.53 |

| Year 9 (total) | 1.52 ** | 0.57 to 2.47 | 0.27 | −0.36 to 0.91 | 1.19 | −0.26 to 2.64 | 2.22 | −0.14 to 4.58 |

| Year 9 males | −1.38 * | −2.73 to −0.03 | −0.34 | −1.25 to 0.56 | −0.37 | −2.43 to 1.70 | −1.76 | −5.16 to 1.64 |

| R2 | 0.072 * | 0.074 ** | 0.095 *** | 0.082 ** | ||||

| Being Away | Fascination | Compatibility | Extent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | |

| Gender (males) | 3.76 * | 0.85 to 6.68 | 1.04 | −1.01 to 3.10 | 0.74 | −0.44 to 1.92 | 1.23 | −0.30 to 2.79 |

| Year 7 (total) | 4.71 ** | 1.72 to 7.71 | 2.16 * | 0.03 to 4.29 | 1.43 * | 0.21 to 2.64 | 2.12 ** | 0.52 to 3.72 |

| Year 7 males | −3.64 | −7.56 to 0.27 | 0.16 | −2.62 to 2.93 | −1.14 | −2.73 to 0.46 | −1.23 | −3.31 to 0.86 |

| Year 8 (total) | 1.93 | −0.86 to 4.71 | 0.93 | −1.05 to 2.91 | 0.09 | −1.04 to 1.22 | 0.58 | −0.91 to 2.07 |

| Year 8 males | −1.12 | −5.20 to 2.95 | −0.77 | −3.66 to 2.12 | 0.3 | −1.35 to 1.96 | −0.58 | −2.75 to 1.59 |

| Year 9 (total) | 1.69 | −1.09 to 4.48 | 0.52 | −1.46 to 2.50 | 0.77 | −0.36 to 1.90 | 1.01 | −0.48 to 2.50 |

| Year 9 males | −0.51 | −4.51 to 3.48 | −1.02 | −3.84 to 1.81 | −0.64 | −2.25 to 0.97 | −0.77 | −2.88 to 1.35 |

| R2 | 0.092 *** | 0.081 ** | 0.04 | 0.054 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leigh, G.; Muminovic, M.; Davey, R. Enjoyed by Jack but Endured by Jill: An Exploratory Case Study Examining Differences in Adolescent Design Preferences and Perceived Impacts of a Secondary Schoolyard. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054221

Leigh G, Muminovic M, Davey R. Enjoyed by Jack but Endured by Jill: An Exploratory Case Study Examining Differences in Adolescent Design Preferences and Perceived Impacts of a Secondary Schoolyard. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054221

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeigh, Gweneth, Milica Muminovic, and Rachel Davey. 2023. "Enjoyed by Jack but Endured by Jill: An Exploratory Case Study Examining Differences in Adolescent Design Preferences and Perceived Impacts of a Secondary Schoolyard" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054221

APA StyleLeigh, G., Muminovic, M., & Davey, R. (2023). Enjoyed by Jack but Endured by Jill: An Exploratory Case Study Examining Differences in Adolescent Design Preferences and Perceived Impacts of a Secondary Schoolyard. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054221