Text4PTSI: A Promising Supportive Text Messaging Program to Mitigate Psychological Symptoms in Public Safety Personnel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design/Ethical Considerations

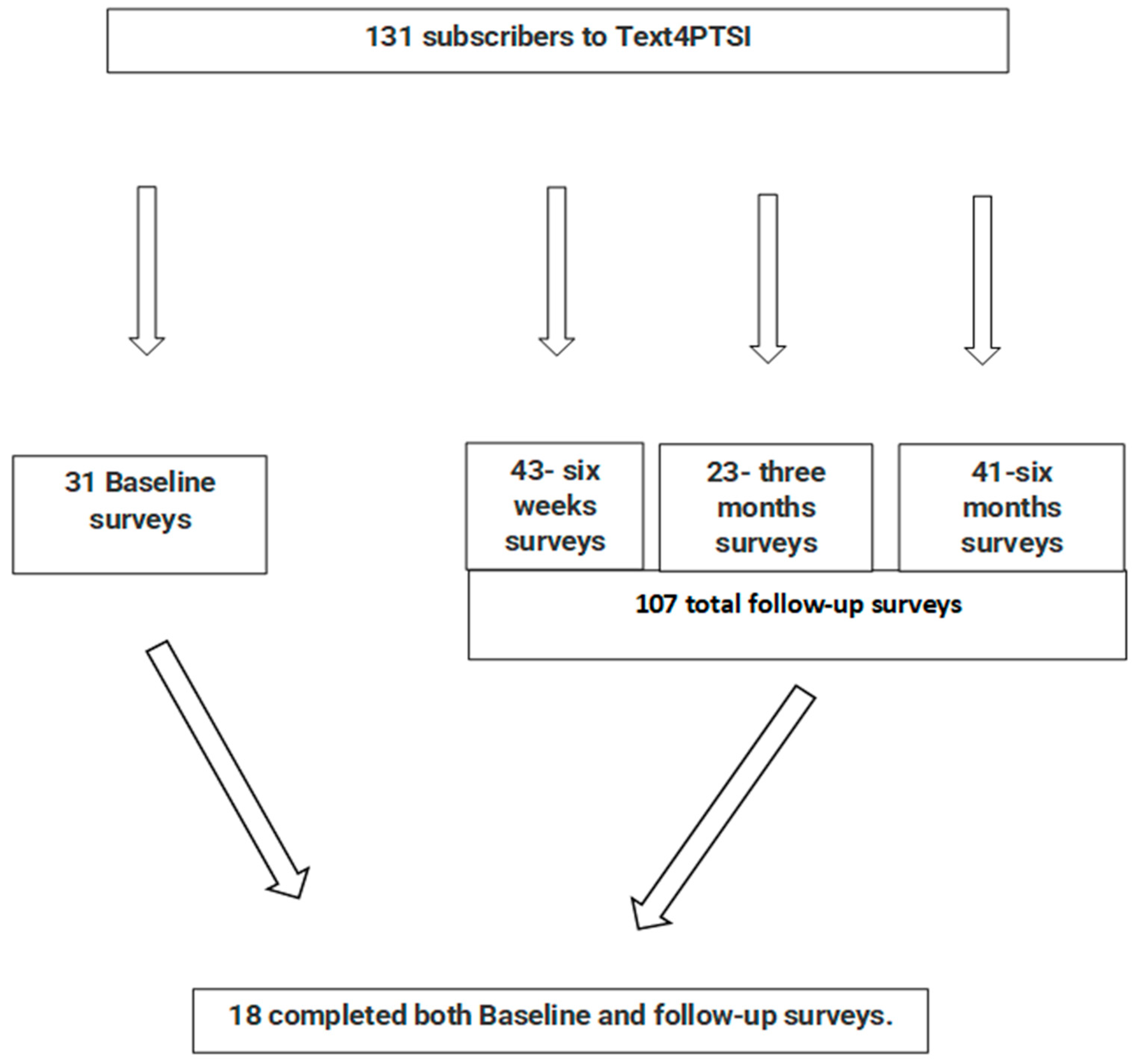

2.2. Data Collection

Letting go of resentment is a gift you give yourself, and it will ease your journey immeasurably. Make peace with everyone, and happiness will be yours. Trauma can feel like a gloomy cloud over all areas of your life. The first step in treatment is to understand what trauma is, the symptoms, and how and why it is treated.

2.3. Outcome Measures

Sample Size Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Analysis of Study Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, G.; Chu, H.; Chen, R.; Liu, D.; Banda, K.J.; O’Brien, A.P.; Jen, H.J.; Chiang, K.J.; Chiou, J.F.; Chou, K.R. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among first responders for medical emergencies during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 05028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Eboreime, E.; Bond, J.; Phung, N.; Eyben, S.; Hayward, J.; Zhang, Y.; MacMaster, F.; Clelland, S.; Greiner, R.; et al. An E-Mental Health Solution to Prevent and Manage Posttraumatic Stress Injuries Among First Responders in Alberta: Protocol for the Implementation and Evaluation of Text Messaging Services (Text4PTSI and Text4Wellbeing). JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e30680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedek, D.M.; Fullerton, C.; Ursano, R.J. First responders: Mental health consequences of natural and human-made disasters for public health and public safety workers. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2007, 28, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleim, B.; Westphal, M. Mental health in first responders: A review and recommendation for prevention and intervention strategies. Traumatology 2011, 17, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, P.T.; Evces, M.; Weiss, D.S. Treating posttraumatic stress disorder in first responders: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, A.; Conrad, D.; Kolassa, I.T.; Rojas, R. Higher sense of coherence is associated with better mental and physical health in emergency medical services: Results from investigations on the revised sense of coherence scale (SOC-R) in rescue workers. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1606628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvolensky, M.J.; Kotov, R.; Schechter, C.B.; Gonzalez, A.; Vujanovic, A.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Crane, M.; Kaplan, J.; Moline, J.; Southwick, S.M.; et al. Post-disaster stressful life events and WTC-related posttraumatic stress, depressive symptoms, and overall functioning among responders to the World Trade Center disaster. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 61, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; MacPhee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2018, 63, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, K.M.; Johnson, J.; Prudenzi, A.; O’Connor, D.B. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for reducing PTSD and psychological distress in first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Oluwasina, F.; Nkire, N.; Agyapong, V.I.O. A Scoping Review on the Prevalence and Determinants of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Military Personnel and Firefighters: Implications for Public Policy and Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakupcak, M.; Luterek, J.; Hunt, S.; Conybeare, D.; McFall, M. posttraumatic stress and its relationship to physical health functioning in a sample of Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans seeking postdeployment VA health care. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2008, 196, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, A.C.; Fear, N.T.; Ehlers, A.; Hacker Hughes, J.; Hull, L.; Earnshaw, M.; Greenberg, N.; Rona, R.; Wessely, S.; Hotopf, M. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder among UK Armed Forces personnel. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, S.L.; White, N.; Fyfe, T.; Matthews, L.R.; Randall, C.; Regehr, C.; White, M.; Alden, L.E.; Buys, N.; Carey, M.G.; et al. Systematic review of posttraumatic stress disorder in police officers following routine work-related critical incident exposure. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, S.; Ashwick, R.; Schlosser, M.; Jones, R.; Rowe, S.; Billings, J. Global prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in police personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Koretz, D.; Merikangas, K.R.; Rush, A.J.; Walters, E.E.; Wang, P.S. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003, 289, 3095–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Chiu, W.T.; Demler, O.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.; Milligan-Saville, J.; Gayed, A.; Deady, M.; Phelps, A.; Dell, L.; Forbes, D.; Bryant, R.A.; Calvo, R.A.; Glozier, N.; et al. Prevalence of PTSD and common mental disorders amongst ambulance personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, C.S.; Ursano, R.J.; Wang, L. Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; An, Y. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD, depression and posttraumatic growth among Chinese firefighters. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.C.; Holmes, L.; Burkle, F.M. The Physical and Mental Health Challenges Experienced by 9/11 First Responders and Recovery Workers: A Review of the Literature. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2019, 34, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edition, F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 2013, 21, 591–643. [Google Scholar]

- Motreff, Y.; Baubet, T.; Pirard, P.; Rabet, G.; Petitclerc, M.; Stene, L.E.; Vuillermoz, C.; Chauvin, P.; Vandentorren, S. Factors associated with PTSD and partial PTSD among first responders following the Paris terror attacks in November 2015. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 121, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.; Marchand, A.; Boyer, R.; Martin, N. Predictors of the development of posttraumatic stress disorder among police officers. J. Trauma Dissociation Off. J. Int. Soc. Study Dissociation ISSD 2009, 10, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, W.; Coutinho, E.S.F.; Figueira, I.; Marques-Portella, C.; Luz, M.P.; Neylan, T.C.; Marmar, C.R.; Mendlowicz, M.V. Rescuers at risk: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of the worldwide current prevalence and correlates of PTSD in rescue workers. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, M.; Burgess, P.; McFarlane, A.C. Post-traumatic stress disorder: Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Psychol. Med. 2001, 31, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.; Tan, L.; Shand, F.; Bryant, R.A.; Harvey, S.B. Can Resilience be Measured and Used to Predict Mental Health Symptomology Among First Responders Exposed to Repeated Trauma? J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, E.; Galea, S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, N.; Moroz, I.; D’Angelo, M.S. Mental health services in Canada: Barriers and cost-effective solutions to increase access. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2020, 33, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Thornicroft, G.; Knapp, M.; Whiteford, H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007, 370, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clin. Textb. Addict. Disord. 2011, 491, 474–501. [Google Scholar]

- Agyapong, V.I.O.; Hrabok, M.; Shalaby, R.; Vuong, W.; Noble, J.M.; Gusnowski, A.; Mrklas, K.; Li, D.; Urichuck, L.; Snaterse, M.; et al. Text4Hope: Receiving Daily Supportive Text Messages for 3 Months During the COVID-19 Pandemic Reduces Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 16, 1326–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong, V.I.; McLoughlin, D.M.; Farren, C.K. Six-months outcomes of a randomised trial of supportive text messaging for depression and comorbid alcohol use disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong, V.I.O.; Juhás, M.; Ohinmaa, A.; Omeje, J.; Mrklas, K.; Suen, V.Y.M.; Dursun, S.M.; Greenshaw, A.J. Randomized controlled pilot trial of supportive text messages for patients with depression. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcox, J.C.; Dobson, R.; Whittaker, R. Old-Fashioned Technology in the Era of “Bling”: Is There a Future for Text Messaging in Health Care? J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e16630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Hollin, I.; Kachnowski, S. A review of the use of mobile phone text messaging in clinical and healthy behaviour interventions. J. Telemed. Telecare 2011, 17, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senanayake, B.; Wickramasinghe, S.I.; Chatfield, M.D.; Hansen, J.; Edirippulige, S.; Smith, A.C. Effectiveness of text messaging interventions for the management of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.L.; Allida, S.M.; Hackett, M.L. Text messages to reduce depressive symptoms: Do they work and what makes them effective? A systematic review. Health Educ. J. 2021, 80, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, V.I.O.; Hrabok, M.; Vuong, W.; Shalaby, R.; Noble, J.M.; Gusnowski, A.; Mrklas, K.J.; Li, D.; Urichuk, L.; Snaterse, M.; et al. Changes in Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Levels of Subscribers to a Daily Supportive Text Message Program (Text4Hope) During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e22423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, V.I.; Mrklas, K.; Juhás, M.; Omeje, J.; Ohinmaa, A.; Dursun, S.M.; Greenshaw, A.J. Cross-sectional survey evaluating Text4Mood: Mobile health program to reduce psychological treatment gap in mental healthcare in Alberta through daily supportive text messages. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beard, C.; Björgvinsson, T. Beyond generalized anxiety disorder: Psychometric properties of the GAD-7 in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu, E.; Shalaby, R.; Eboreime, E.; Nkire, N.; Lawal, M.A.; Agyapong, B.; Pazderka, H.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Adu, M.K.; Mao, W.; et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms in Residents of Fort McMurray 12 Months Following the 2020 Flooding. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 844907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Herman, D.S.; Huska, J.A.; Keane, T.M. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX, USA, 24 October 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, W.; Adu, M.; Eboreime, E.; Shalaby, R.; Nkire, N.; Agyapong, B.; Pazderka, H.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Owusu, E.; Oluwasina, F.; et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, and Wildfires: A Fifth-Year Postdisaster Evaluation among Residents of Fort McMurray. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, M.A.; Senyak, J. Sample Size Calculators 2021. Available online: https://sample-size.net/sample-size-study-paired-t-test/ (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- International Business Machines (IBM) Corp. Statistics for Windows; Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, B.S.; Wessely, S. Clinical Trials in Psychiatry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chen, M.C.; Chou, F.H.; Sun, F.C.; Chen, P.C.; Tsai, K.Y.; Chao, S.S. The relationship between quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder or major depression for firefighters in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, M.A.; Crawford, J.M.; Wilkins, J.R.; Fernandez, A.R.; Studnek, J.R. An assessment of depression, anxiety, and stress among nationally certified EMS professionals. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2013, 17, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracie Shea, M.; Reddy, M.K.; Tyrka, A.R.; Sevin, E. Risk factors for post-deployment posttraumatic stress disorder in national guard/reserve service members. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, J.A.; Francis, A.J.; Paxton, S.J. Caring for the country: Fatigue, sleep and mental health in Australian rural paramedic shiftworkers. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.C.; Zimering, R.; Daly, E.; Knight, J.; Kamholz, B.W.; Gulliver, S.B. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological symptoms in trauma-exposed firefighters. Psychol. Serv. 2012, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradus, J.L. Epidemiology of PTSD; National Center for PTSD (United States Department of Veterans Affairs): White River Junction, VT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, H.C.; Landry, C.A.; Ogunade, A.; Carleton, R.N.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D. Why Do Public Safety Personnel Seek Tailored Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy? An Observational Study of Treatment-Seekers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, L.; Matthews, L.; Wagner, S.; Fyfe, T.; Randall, C.; Regehr, C.; White, M.; Buys, N.; Carey, M.; Corneil, W. Systematic literature review of psychological interventions for first responders. Work Stress 2021, 35, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.S.; Di Nota, P.M.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N. Peer Support and Crisis-Focused Psychological Interventions Designed to Mitigate Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries among Public Safety and Frontline Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winders, W.T.; Bustamante, N.D.; Garbern, S.C.; Bills, C.; Coker, A.; Trehan, I.; Osei-Ampofo, M.; Levine, A.C. Establishing the Effectiveness of Interventions Provided to First Responders to Prevent and/or Treat Mental Health Effects of Response to a Disaster: A Systematic Review. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 15, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, V.; Cuijpers, P.; Nyklícek, I.; Riper, H.; Keyzer, J.; Pop, V. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Li, X.J.; Liu, Y.Z.; Lang, Y.; Lin, L.; Yang, X.J.; Jiang, X.J. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (ICBT-i) Improves Comorbid Anxiety and Depression-A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathbone, A.L.; Prescott, J. The Use of Mobile Apps and SMS Messaging as Physical and Mental Health Interventions: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Miguel-Cruz, A.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Cruikshank, E.; Baghoori, D.; Kaur Chohan, A.; Laidlaw, A.; White, A.; Cao, B.; Agyapong, V.; et al. Virtual Trauma-Focused Therapy for Military Members, Veterans, and Public Safety Personnel With Posttraumatic Stress Injury: Systematic Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e22079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, V.I.; Ahern, S.; McLoughlin, D.M.; Farren, C.K. Supportive text messaging for depression and comorbid alcohol use disorder: Single-blind randomised trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong, V.; Mrklas, K.; Juhas, M.; Omeje, J.; Ohinmaa, A.; Dursun, S.; Greenshaw, A. Mobile health program to reduce psychological treatment gap in mental healthcare in Alberta through daily supportive text messages–Cross-sectional survey evaluating Text4Mood. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabyn, S.; Araya, R.; Barkham, M.; Bower, P.; Cooper, C.; Duarte, A.; Kessler, D.; Knowles, S.; Lovell, K.; Littlewood, E.; et al. The second Randomised Evaluation of the Effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and Acceptability of Computerised Therapy (REEACT-2) trial: Does the provision of telephone support enhance the effectiveness of computer-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy? A randomised controlled trial. Health Technol. Assess. 2016, 20, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; McCall, H.C.; Thiessen, D.L.; Huang, Z.; Carleton, R.N.; Dear, B.F.; Titov, N. Initial Outcomes of Transdiagnostic Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Tailored to Public Safety Personnel: Longitudinal Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. Building Your Resilience. What Is Resilience? 2012. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Wu, Y.; Sang, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.C.; Margraf, J. The Relationship Between Resilience and Mental Health in Chinese College Students: A Longitudinal Cross-Lagged Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbrandij, M.; Kunovski, I.; Cuijpers, P. Effectiveness of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, J.M.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Urichuk, L.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Text4Support Mobile-Based Programming for Individuals Accessing Addictions and Mental Health Services-Retroactive Program Analysis at Baseline, 12 Weeks, and 6 Months. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 640795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 2: Do they really think differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingli, A.; Seychell, D. The New Digital Natives. In Cutting the Chord; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen, M.; Bendtsen, P. Feasibility and user perception of a fully automated push-based multiple-session alcohol intervention for university students: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2014, 2, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daikeler, J.; Bošnjak, M.; Lozar Manfreda, K. Web versus other survey modes: An updated and extended meta-analysis comparing response rates. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2020, 8, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazeem, B.; Abbas, K.S.; Amin, M.A.; El-Shahat, N.A.; Malik, B.; Kalantary, A.; Eltobgy, M. The effectiveness of incentives for research participation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Sample A N = 18 (%) | Sample B N = 69 (%) | Total a N (%) | Chi-Squared /Fisher’s Exact b | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Safety Personnel | |||||

| Emergency department health workers | 4 (22.2) | 4 (6.7) | 8 (10.3) | 6.97 b | 0.11 |

| Paramedics | 4 (22.2) | 11 (18.3) | 15 (19.2) | ||

| Firefighters | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.6) | ||

| Police/Law enforcement agents | 8 (44.4) | 21 (35.0) | 29 (37.2) | ||

| Other | 2 (11.1) | 22 (36.7) | 24 (30.8) | ||

| Age | |||||

| ≤30 y | 5 (29.4) | 9 (14.3) | 14 (17.5) | 2.60 | 0.46 |

| 31–45 y | 6 (35.3) | 25 (39.7) | 31 (38.8) | ||

| 46–60 y | 5 (29.4) | 20 (31.7) | 25 (31.3) | ||

| >60 y | 1 (5.9) | 9 (14.3) | 10 (12.5) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 12 (66.7) | 35 (55.6) | 47 (58.0) | 0.80 b | 0.72 |

| Male | 6 (33.3) | 25 (39.7) | 31 (38.3) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.8) | 3 (3.7) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 12 (70.6) | 51 (79.7) | 63 (77.8) | 7.79 b | 0.07 |

| Indigenous | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.3) | 4 (4.9) | ||

| Asian | 1 (5.9) | 7 (10.9) | 8 (9.9) | ||

| African descent | 1 (5.9) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (2.5) | ||

| Other | 3 (17.6) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (4.9) | ||

| Education Level | |||||

| High school diploma | 2 (11.8) | 10 (15.6) | 12 (14.8) | 0.57 b | 0.99 |

| Postsecondary education | 15 (88.2) | 53 (82.8) | 68 (84.0) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Employment Status | |||||

| Employed | 15 (88.2) | 56 (87.5) | 71 (87.7) | 0.01 | 0.94 |

| Unemployed | 2 (11.8) | 8 (12.5) | 10 (12.3) | ||

| Relationship Status | |||||

| In a relationship | 11 (64.7) | 47 (74.6) | 58 (72.5) | 6.32 b | 0.08 |

| Single | 3 (17.6) | 14 (22.2) | 17 (21.3) | ||

| Separated or divorced | 1 (5.9) | 2 (3.2) | 3 (3.8) | ||

| Widowed | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) | ||

| Housing Status | |||||

| Own a home | 12 (70.6) | 45 (70.3) | 57 (70.4) | 0.58 | 0.82 |

| Renting | 3 (17.6) | 14 (21.9) | 17 (21.0) | ||

| Living with family | 2 (11.8) | 5 (7.8) | 7 (8.6) | ||

| A. Distribution of baseline prevalence of mental health conditions between participants who completed only the baseline survey and participants who completed the baseline and any follow-up survey (sample A) | |||||

| Variables, n (%) | Baseline and Follow-Up N (%) | Baseline Only N (%) | Total N (%) | Chi-Square | p-Value |

| Likely MDD a | N = 17 | N = 11 | N = 28 | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| At most mild depression | 9 (52.9) | 5 (45.5) | 14 (50.0) | ||

| Moderate to severe depression | 8 (47.1) | 6 (54.5) | 14 (50.0) | ||

| Likely GAD b | N = 16 | N = 11 | N = 27 | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| At most mild GAD | 10 (62.5) | 6 (54.5) | 16 (59.3) | ||

| Moderate to severe GAD | 6 (37.5) | 5 (45.5) | 11 (40.7) | ||

| Low resilience c | N = 18 | N = 11 | N = 29 | 3.16 | 0.08 |

| Normal to high resilience | 14 (77.8) | 5 (45.5) | 19 (65.5) | ||

| Low resilience | 4 (22.2) | 6 (54.5) | 10 (34.5) | ||

| Likely PTSD d | N = 15 | N = 10 | N = 25 | * | 0.03 |

| Unlikely PTSD | 13 (86.7) | 4 (40.0) | 17 (68.0) | ||

| Likely PTSD | 2 (13.3) | 6 (60.0) | 8 (32.0) | ||

| B. Distribution of follow-up prevalence of mental health conditions between participants who completed only follow-up and participants who completed the baseline and any follow-up survey (sample A) | |||||

| Variables, n (%) ** | Baseline and Follow-Up, N = 18 (%) | Follow-Up Only, N = 56 (%) | Total N = 74 (%) | Chi-Square | p-Value |

| Likely MDD a | N = 17 | N = 54 | N = 71 | 2.97 | 0.09 |

| At most mild depression | 15 (88.2) | 36 (66.7) | 51 (71.8) | ||

| Moderate to severe depression | 2 (11.8) | 18 (33.3) | 20 (28.2) | ||

| Likely GAD b | N = 16 | N = 53 | N = 69 | 0.58 | 0.45 |

| At most mild GAD | 13 (81.3) | 38 (71.7) | 51 (73.9) | ||

| Moderate to severe GAD | 3 (18.8) | 15 (28.3) | 18 (26.1) | ||

| Low resilience c | N = 18 | N = 56 | N = 74 | 1.42 | 0.23 |

| Normal to high resilience | 14 (77.8) | 35 (62.5) | 49 (66.2) | ||

| Low resilience | 4 (22.2) | 21 (37.5) | 25 (33.8) | ||

| Likely PTSD d | N = 16 | N = 51 | N = 67 | 0.39 | 0.53 |

| Unlikely PTSD | 12 (75.0) | 34 (66.7) | 46 (68.7) | ||

| Likely PTSD | 4 (25.0) | 17 (33.3) | 21 (31.3) | ||

| Clinical Condition | Prevalence n (%) | Change from Baseline, % | X2 (df) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Baseline | Follow-Up | ||||

| Likely MDD a | 17 | 8 (47.1) | 2 (11.8) | −35.3 | 2.55 (1) | 0.03 |

| Likely GAD b | 16 | 6 (37.5) | 3 (18.8) | −18.7 | 6.15 (1) | 0.25 |

| Low resilience c | 18 | 4 (22.2) | 4 (22.2) | 0 | 18.0 (1) | 0.99 |

| Likely PTSD d | 15 | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | −6.6 | 1.29 (1) | 0.99 |

| Measure | Scores | Change from Baseline, % | Mean Difference (95% CI) | p Value | t Value (df) | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline Score, Mean (SD) | Follow-Up, Mean (SD) | ||||||

| PHQ-9 a | 17 | 8.41 (5.46) | 6.24 (4.98) | 25.8 | −2.17 (−0.45–4.81) | 0.098 | 1.76 (16) | 0.42 |

| GAD-7 b | 16 | 8.38 (5.83) | 6.31 (5.11) | 24.7 | −2.07 (−0.45–3.67) | 0.02 | 2.73 (15) | 0.38 |

| BRS c | 18 | 3.29 (0.85) | 3.28 (0.72) | 0.3 | −0.01 (−0.25–0.27) | 0.94 | 0.08 (17) | 0.01 |

| PCL-C d | 15 | 32.13 (11.69) | 29.07 (10.56) | 9.5 | −3.07 (−2.76–8.89) | 0.28 | 1.13 (14) | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Shalaby, R.; Eboreime, E.; Agyapong, B.; Phung, N.; Eyben, S.; Wells, K.; Hilario, C.; Dias, R.d.L.; Jones, C.; et al. Text4PTSI: A Promising Supportive Text Messaging Program to Mitigate Psychological Symptoms in Public Safety Personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054215

Obuobi-Donkor G, Shalaby R, Eboreime E, Agyapong B, Phung N, Eyben S, Wells K, Hilario C, Dias RdL, Jones C, et al. Text4PTSI: A Promising Supportive Text Messaging Program to Mitigate Psychological Symptoms in Public Safety Personnel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054215

Chicago/Turabian StyleObuobi-Donkor, Gloria, Reham Shalaby, Ejemai Eboreime, Belinda Agyapong, Natalie Phung, Scarlett Eyben, Kristopher Wells, Carla Hilario, Raquel da Luz Dias, Chelsea Jones, and et al. 2023. "Text4PTSI: A Promising Supportive Text Messaging Program to Mitigate Psychological Symptoms in Public Safety Personnel" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054215

APA StyleObuobi-Donkor, G., Shalaby, R., Eboreime, E., Agyapong, B., Phung, N., Eyben, S., Wells, K., Hilario, C., Dias, R. d. L., Jones, C., Brémault-Phillips, S., Zhang, Y., Greenshaw, A. J., & Agyapong, V. I. O. (2023). Text4PTSI: A Promising Supportive Text Messaging Program to Mitigate Psychological Symptoms in Public Safety Personnel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054215