Effects of Workplace Ostracism on Burnout among Nursing Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Mediated by Emotional Labor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Workplace Ostracism

2.2. Burnout

2.3. Emotional Labor

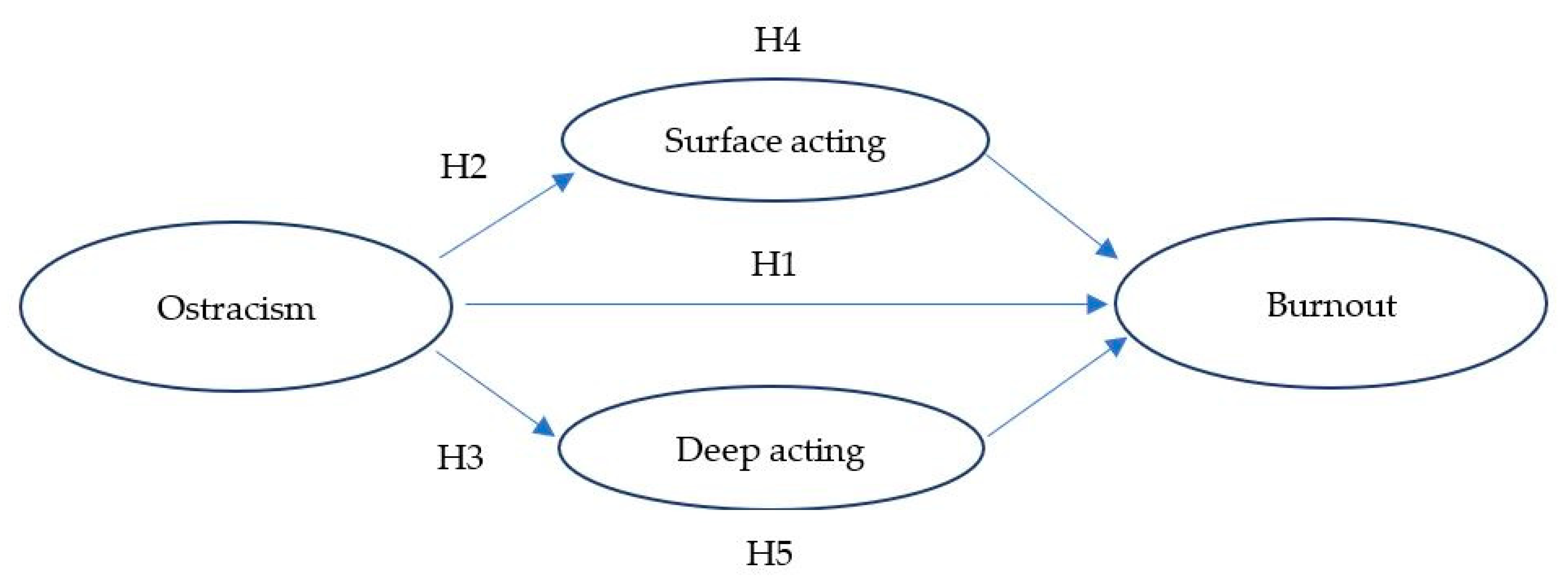

2.4. Hypothesis

2.4.1. Workplace Ostracism and Job Burnout

2.4.2. Workplace Ostracism and Emotional Labor

2.4.3. Emotional Labor as a Mediator between Workplace Ostracism and Job Burnout

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Burnout

3.2.2. Ostracism

3.2.3. Emotional Labor

4. Result

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.1.1. Ostracism

4.1.2. Surface Acting

4.1.3. Deep Acting

4.1.4. Exhaustion

4.1.5. Cynicism

4.1.6. Professional Efficacy

4.2. Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falatah, R. The Impact of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic on Nurses’ Turnover Intention: An Integrative Review. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donna, M.K.; Michele, H.; Ranit, M.; Howard, C.; Otmar, K. Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1743–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, T. COVID-19: Protecting health-care workers. Lancet 2020, 395, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.H.; Yang, C.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Huang, L.L.; Lin, C.H.; Huang, C.T.; Yeh, T.F. Associations of Workplace Violence and Job Stress with Nursing Staff Turnover Intention. Hospital 2020, 53, 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain, G.; Chênevert, D. Job demands resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Occup. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.M.; Pai, F.U.; Chou, S.C. Administrators’ Heavy Stress! The Effects of Teachers’ Personality Traits, Work Pressure and Pressure Response Tactics on Job Burnout. J. Glob. Technol. Manag. Educ. 2019, 8, 70–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.Y. A Review of Workplace Ostracism Research. Technol. Hum. Educ. Q. 2017, 4, 96–111. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.D.; Sommer, K.L. Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.L.; Brown, D.J.; Berry, J.W.; Lian, H. The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1348–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, B.; Huang, C.; Song, B. When workplace ostracism leads to burnout: The roles of job self-determination and future time orientation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 30, 2465–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.S.; Daniels, M.A.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Greguras, G.J. Emotional labor actors: A latent profile analysis of emotional labor strategies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Tews, M.J. Emotional labor: A conceptualization and scale development. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlan, R.T.; Kelly, K.M.; Schepman, S.; Schneider, K.T.; Zárate, M.A. Language exclusion and the consequences of perceived ostracism in the workplace. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2006, 10, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlan, R.T.; Noel, J. The influence of workplace exclusion and personality on counterproductive work behaviours: An interactionist perspective. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2009, 18, 477–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; O’Reilly, J.; Wang, W. Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace ostracism. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. On the meaning of Maslach’s three dimensions of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.G. Employee burnout and perceived social support. J. Health Hum. Resour. Adm. 1994, 16, 350–367. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seda-Gombau, G.; Montero-Alía, J.J.; Moreno-Gabriel, E.; Torán-Monserrat, P. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Burnout in Primary Care Physicians in Catalonia. Int. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 18, 9031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanullah, S.; Shankar, R.R. The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: A review. Multidiscip. Digit. Publ. Inst. 2020, 8, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, A.; Sharma, R.; Hossain, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Purohit, N. Burnout among healthcare providers during COVID-19: Challenges and evidence-based interventions. Indian J. Med. Ethics 2020, 5, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Mousavi-Roknabadi, R.S. Burnout among Healthcare Providers of COVID-19; a Systematic Review of Epidemiology and Recommendations. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A.R. The Managed Heart; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtoldt, M.N.; Rohrmann, S.; De Pater, I.E.; Beersma, B. The primacy of perceived emotion recognition buffers negative effects of emotional labor. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, X.; Sun, P.; Li, X. Coping with workplace ostracism: The roles of emotional exhaustion and resilience in deviant behavior. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard-Grace, R.; Knox, M.; Huang, B.; Hammer, H.; Kivlahan, C.; Grumbach, K. Burnout and Health Care Workforce Turnover. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, 17, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.; Tang, K.S.; Tang, S. Psychological capital as a moderator between emotional labor, burnout, and job satisfaction among school teachers in China. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2011, 18, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G. Workplace Ostracism, Emotional Labor, Nurse-Patient Relationship and Turnover Intention: A Process Model of Workplace Ostracism and Its Consequence in Nursing Professional. ISCTE-Inst. Univ. De Lisb. 2018. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/0008dafdc18ff361ec52d32232b90a94/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanasy, N.M.; Daus, C.S. Emotion in the workplace: The new challenge for managers. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2002, 16, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 349–444. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Development and validation of the Emotional Labour Scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models With Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. Available online: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/35622/b1378752.0001.001.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 7: A Guide to the Program and Applications, 2nd ed.; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1624759 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Heaphy, E.D.; Dutton, J.E. Positive social interactions and the human body at work: Linking organizations and physiology. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.Y.; Lee, B.; Kwon, O.J.; Kim, M.S.; Sim, K.L.; Choi, Y.H. Emotional labor, burnout, medical error, and turnover intention among South Korean nursing staff in a University hospital setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 4 | 1.6% |

| Female | 246 | 98.4% | |

| Age (years) | 20–29 | 29 | 11.6% |

| 30–39 | 85 | 34% | |

| 40–49 | 109 | 43.6% | |

| 50–59 | 21 | 8.4% | |

| 60 and above | 6 | 2.4% | |

| Educational level | Junior high school | 0 | 0% |

| Senior high school | 14 | 5.6% | |

| University | 224 | 89.6% | |

| Master’s and doctorate | 12 | 4.8% | |

| Supervisor | Yes | 30 | 12% |

| No | 220 | 88% | |

| Tenure (years) | 5 or less | 29 | 8% |

| 6–10 | 40 | 16% | |

| 11–20 | 124 | 49.6% | |

| 21–30 | 51 | 20.4% | |

| 31 or over | 6 | 2.4% | |

| Institution served | Medical center | 33 | 13.2% |

| Regional hospital | 67 | 26.8% | |

| District hospital | 30 | 12% | |

| Clinic | 29 | 11.6% | |

| Long-term nursing organization | 91 | 36.4% | |

| Total | 250 | 100% |

| Step 1 | |||||

| Burnout (DV) | |||||

| β | R2 | ΔR2 | F | t | |

| Ostracism | 0.214 ** | 0.046 | 0.042 | 11.929 | 3.454 |

| Surface acting | 0.136 * | 0.019 | 0.015 | 4.686 | 2.165 |

| Deep acting | −0.046 | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.537 | −0.733 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Burnout (DV) | |||||

| β | R2 | ΔR2 | F | t | |

| IV Ostracism | 0.176 ** | 2.928 | |||

| Mediator Surface acting | 0.280 *** | 0.123 | 0.116 | 17.278 | 4.651 |

| IV ostracism | 0.209 ** | 3.383 | |||

| Mediator Deep acting | −0.108 | 0.058 | 0.050 | 7.550 | −1.752 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, F.-H.; Tan, S.-L. Effects of Workplace Ostracism on Burnout among Nursing Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Mediated by Emotional Labor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054208

Yang F-H, Tan S-L. Effects of Workplace Ostracism on Burnout among Nursing Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Mediated by Emotional Labor. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054208

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Feng-Hua, and Shih-Lin Tan. 2023. "Effects of Workplace Ostracism on Burnout among Nursing Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Mediated by Emotional Labor" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054208

APA StyleYang, F.-H., & Tan, S.-L. (2023). Effects of Workplace Ostracism on Burnout among Nursing Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Mediated by Emotional Labor. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054208