“My [Search Strategies] Keep Missing You”: A Scoping Review to Map Child-to-Parent Violence in Childhood Aggression Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Violence and Aggression

1.2. Operational Definition

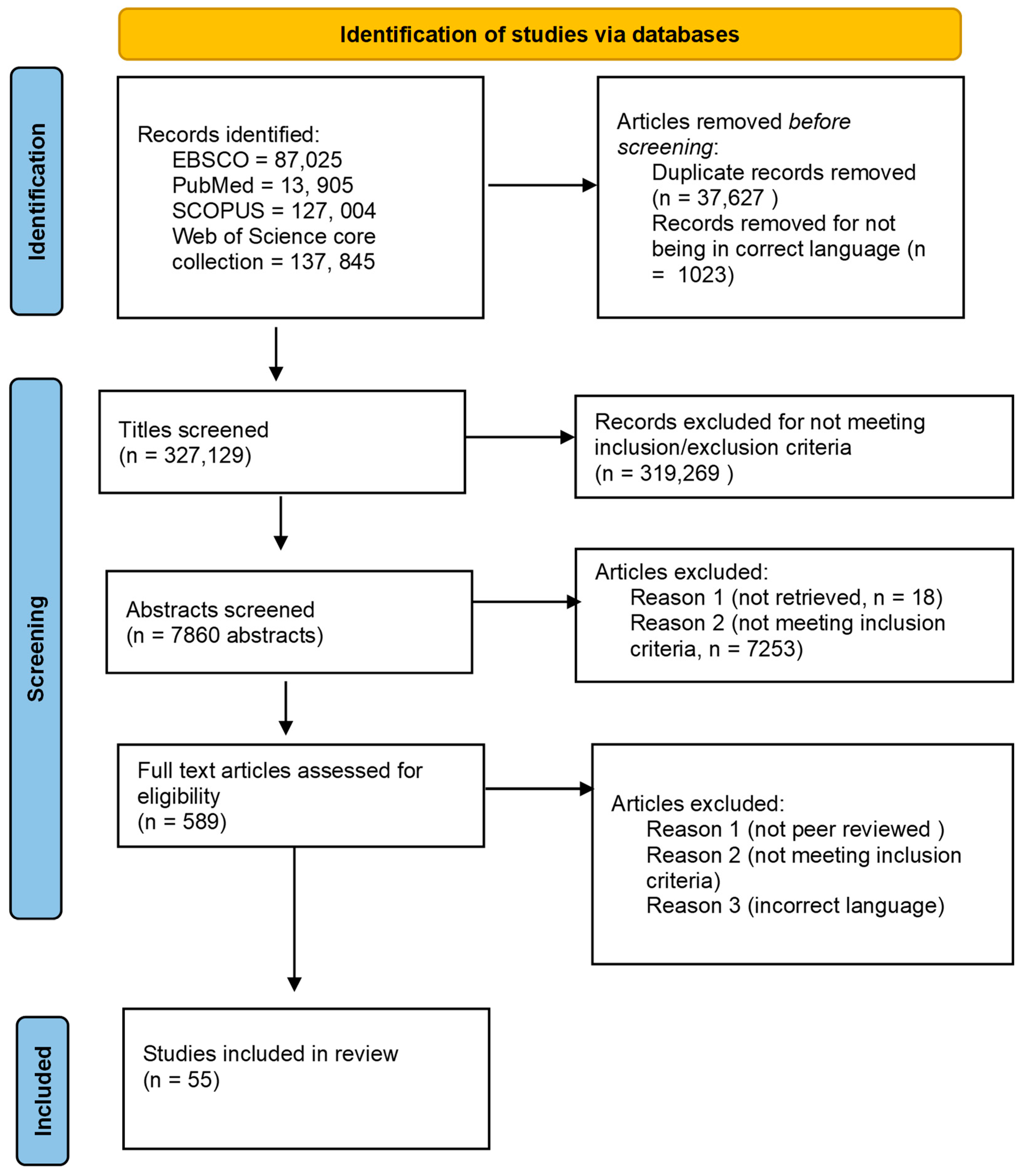

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.1.1. Stage One

2.1.2. Stage Two

2.1.3. Stage Three

2.1.4. Stage Four

- Author(s), year of publication, study location

- Study populations (parent population and child population)

- Aims of the study

- Main findings

- Methodology

- Language used to identify child-parent violence

- How the paper conceptualised the phenomenon

2.1.5. Stage Five

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Indicating Childhood Distress or Developmental Needs

4.2. Indicating Deviance

4.3. Prioritising Parents as Victims

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molla-Esparza, C.; Aroca-Montolío, C. Menores que maltratan a sus progenitores: Definición integral y su ciclo de violencia. Anu. Psicol. Juríd. 2018, 28, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro-García, P.; Cutillas-Poveda, M.J.; Sánchez-Villegas, S.; Sola-Ocetta, M. Fuerza exterior, debilidad interior. Ejes fundamentales de la violencia filio-parental. Rev. Sobre Infanc. Adolesc. 2019, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.; Nixon, J.; Parr, S. Mother abuse: A matter of youth justice, child welfare or domestic violence? J. Law Soc. 2010, 37, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micucci, J.A. Adolescents who assault their parents: A family systems approach to treatment. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1995, 32, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.F.; Newcorn, J.H.; Saylor, K.E.; Amann, B.H.; Scahill, L.; Robb, A.S.; Jensen, P.S.; Vitiello, B.; Findling, R.L.; Buitelaar, J.K. Maladaptive aggression: With a focus on impulsive aggression in children and adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A.; Shon, P.C. Exploring fatal and non-fatal violence against parents: Challenging the orthodoxy of abused adolescent perpetrators. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2018, 62, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymouth, B.B.; Buehler, C.; Zhou, N.; Henson, R.A. A meta-analysis of parent–adolescent conflict: Disagreement, hostility, and youth maladjustment. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2016, 8, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Rivera, S.; García, M.V.H. Theoretical framework and explanatory factors for child or adolescent-to-parent violence and abuse. A scoping review. An. Psicol. 2020, 36, 220–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell, B.; Monk, P. Adolescent-to-parent abuse: A qualitative overview of common themes. J. Fam. Issues 2004, 25, 1072–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M.; McEwan, T.E.; Purcell, R.; Ogloff, J.R. Sixty years of child-to-parent abuse research: What we know and where to go. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 38, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, N. “It’s Like Living in a House with Constant Tremors, and Every So Often, There’s an Earthquake” A Glaserian Grounded Theory Study into Harm to Parents, Caused by the Explosive and Controlling Impulses of Their Pre-Adolescent Children. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Condry, R.; Miles, C. Adolescent to parent violence: Framing and mapping a hidden problem. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2014, 14, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A. ‘The terrorist in my home’: Teenagers’ violence towards parents–constructions of parent experiences in public online message boards. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2011, 16, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloud, E.J. Adolescent-to-Parent Violence and Abuse (APVA): An Investigation into Prevalence, Associations and Predictors in a Community Sample. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moulds, L.; Day, A.; Mayshak, R.; Mildred, H.; Miller, P. Adolescent violence towards parents—Prevalence and characteristics using Australian Police Data. Aust. N. Z. J. Criminol. 2019, 52, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, C.W.; Fischer, J.L.; Kidwell, J.S. Teenage violence toward parents: A neglected dimension of family violence. J. Marriage Fam. 1985, 47, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, R.; Calvete, E.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Orue, I. Child-to-Parent Aggression in adolescents: Prevalence and reasons. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Developmental Psychology, International Proceedings Division, Lausanne, Switzerland, 3–7 September 2013; pp. 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, M.L.; McEwan, T.E.; Purcell, R.; Huynh, M. The Abusive Behaviour by Children-Indices (ABC-I): A measure to discriminate between normative and abusive child behaviour. J. Fam. Violence 2019, 34, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lewis, G.; Evans, L. Understanding aggressive behaviour across the lifespan. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. The passing of the Oedipus complex. Int. J. Psycho-Anal. 1924, 5, 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, A. Notes on aggression. Bull. Menn. Clin. 1949, 13, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Some pathological processes set in train by early mother-child separation. J. Ment. Sci. 1953, 99, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waffenschmidt, S.; Knelangen, M.; Sieben, W.; Bühn, S.; Pieper, D. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: A methodological systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, N. Holidays for children and families in need: An exploration of the research and policy context for social tourism in the UK. Child. Soc. 2005, 19, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I. A systematic review of youth-to-parent aggression: Conceptualization, typologies, and instruments. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easson, W.M.; Steinhilber, R.M. Murderous aggression by children and adolescents. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.A.; Krienert, J.L. A decade of child-instigated family violence: Comparative analysis of child—Parent violence and parricide examining offender, victim, and event characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents, 1995–2005. J. Interpers. Violence 2009, 24, 1450–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.B.; McGuire, S.N.; Meadan, H.; Martin, M.R.; Terol, A.K.; Haidar, B.; Fanta, A.S. Impact of Challenging Behaviour on Marginalised and Minoritised Caregivers of Children with Disabilities. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar]

- Ament, A. The boy who did not cry. Child Welf. 1972, 51, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley, K. Adopting children with high therapeutic needs: Staying committed over the long haul. Adopt. Foster. 2017, 41, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinson, V.; Quinlan, C. De-criminalising adolescent to parent violence under s 76 Serious Crime Act 2015 (c. 9). J. Crim. Law 2020, 84, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Bertino, L.; Gonzalez, Z.; Montes, Y.; Padilla, P.; Pereira, R. Child-to-parent violence in adolescents: The perspectives of the parents, children, and professionals in a sample of Spanish focus group participants. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R. Violence in adolescence. J. Anal. Psychol. 1967, 12, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desir, M.P.; Karatekin, C. Parent-and sibling-directed aggression in children of domestic violence victims. Violence Vict. 2018, 33, 886–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubet, S.L.; Ostrosky, M.M. The impact of challenging behaviour on families: I don’t know what to do. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2015, 34, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubet, S.L.; Ostrosky, M.M. Parents’ experiences when seeking assistance for their children with challenging behaviours. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2016, 36, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, H.; Walsh, T. Adolescent family violence: What is the role for legal responses? Syd. Law Rev. 2018, 40, 499–526. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G.K. An 11-year-old boy with Asperger’s disorder presenting with aggression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helin, D.; Chevalier, V.; Born, M. Ces adolescents qui agressent leur mère! Neuropsychiatr. Enfance Adolesc. 2004, 52, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, T. Le «crying boy». Imagin. Inconsc. 2009, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A.; Lewis, S. Constituting child-to-parent violence: Lessons from England and Wales. Br. J. Criminol. 2021, 61, 792–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, M.; Ott, N.; Hopkins, L. Responding to Adolescent Violence in the Home–A Community Mental Health Approach. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2021, 41, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A.; Derry, A. Violence of French adolescents toward their parents: Characteristics and contexts. J. Adolesc. Health 1999, 25, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, K.; Brady, N.C.; Warren, S.F.; Fleming, K.K. Mothers’ perspectives on challenging behaviours in their children with fragile X syndrome. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 44, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruche, U.M.; Draucker, C.B.; Al-Khattab, H.; Cravens, H.A.; Lowry, B.; Lindsey, L.M. The challenges for primary caregivers of adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorders. J. Fam. Nurs. 2015, 21, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.; Kuczynski, L. Deconstructing noncompliance: Parental experiences of children’s challenging behaviours in a clinical sample. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being 2018, 13, 1563432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, N. “I’m meant to be his comfort blanket, not a punching bag”–Ethnomimesis as an exploration of maternal child to parent violence in pre-adolescents. Qual. Soc. Work 2021, 20, 1317–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporer, K. Aggressive children with mental illness: A conceptual model of family-level outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 447–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Tuffin, K.; Niland, P. “It’s like he just goes off, BOOM!”: Mothers and grandmothers make sense of child-to-parent violence. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worcester, J.A.; Nesman, T.M.; Mendez, L.M.R.; Keller, H.R. Giving voice to parents of young children with challenging behavior. Except. Child. 2008, 74, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.S.; Muftic, L.R.; Bouffard, L.A. Factors Influencing Law Enforcement Responses to Child to Parent Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 4979–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, H.; Martín, A.M. The behavioural specificity of child or adolescent-to-parent violence and abuse.Explores frequency of different forms. An. Psicol. 2020, 36, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, M.H.; Fawzi, M.M.; Fouad, A.A. Parent abuse by adolescents with first-episode psychosis in Egypt. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyo-Bilbao, D.; Orue, I.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Calvete, E. Multivariate models of child-to-mother violence and child-to-father violence among adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2020, 12, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I.; Jaureguizar, J. Child-to-parent violence: Profile of abusive adolescents and their families. J. Crim. Justice 2010, 38, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I.; Arnoso, A.; Elgorriaga, E. The clinical profile of adolescent offenders of child or adolescent-to-parent violence and abuse. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 131, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, P.; Pérez, B.; Contreras, L.; Cano-Lozano, M.C. Analysing child or adolescent-to-parent violence and abuse in Chilean adolescents: Prevalence and reasons. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 11, 604956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, T.D.; Edmonds, W.A.; Dann, K.T.; Burnett, K.F. The clinical and adaptive features of young offenders with histories of child-parent violence. J. Fam. Violence 2010, 25, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, B.D.; Rueter, M.A. Contributions of parent–adolescent negative emotionality, adolescent conflict, and adoption status to adolescent externalising behaviours. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2011, 40, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratcoski, P.C. Youth violence directed toward significant others. J. Adolesc. 1985, 8, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.O.; Shanok, S.S.; Grant, M.; Ritvo, E. Homicidally aggressive young children: Neuropsychiatric and experiential correlates. Am. J. Psychiatry 1983, 140, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- López-Martínez, P.; Montero-Montero, D.; Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Martínez-Ferrer, B. The Role of Parental Communication and Emotional Intelligence in Child-to-Parent Violence. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.F.; Del Vecchio, T.; Slep, A.M.S. Infant externalising behaviour as a self-organising construct. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.F.; Del Vecchio, T.; Slep, A.M.S. The emergence and evolution of infant externalising behaviour. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Romero-Abrio, A.; León-Moreno, C.; Villarreal-González, M.E.; Musitu-Ferrer, D. Suicidal ideation, psychological distress and child-to-parent violence: A gender analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3273–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, S.D.; Calhoun, S.L.; Aggarwal, R.; Baker, C.; Mathapati, S.; Anderson, R.; Petersen, C. Explosive, oppositional, and aggressive behaviour in children with autism compared to other clinical disorders and typical children. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Kazdin, A.E. Parent-directed physical aggression by clinic-referred youths. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2002, 31, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski-Sims, E.; Rowe, A. The relationship between childhood adversity, attachment, and internalising behaviours in a diversion program for child-to-mother violence. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 72, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L.; Larocque, D.; Vitaro, F.; Tremblay, R.E. Verbal and physical abuse toward mothers: The role of family configuration, environment, and coping strategies. J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, D.; Vázquez, M.J.; Gallego, R.; Gancedo, Y.; Novo, M. Adolescent-to-parent violence: Psychological and family adjustment. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3221–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecina, M.L.; Chacón, J.C.; Piñuela, R. Child-to-parent violence and dating violence through the moral foundations theory: Same or different moral roots? Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 597679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cai, C.; Wang, Z.; Tao, M.; Liu, X.; Craig, W. Adolescent-to-Mother psychological aggression: The role of father violence and maternal parenting style. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 98, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.D.; Bednar, L.M. Foster parent perceptions of placement breakdown. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2006, 28, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.V. Physically abused parents. J. Fam. Violence 1986, 1, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaunay, E.; Purper-Ouakil, D.; Mouren, M.C. Troubles oppositionnels de l’enfant et tyrannie intrafamiliale: Vers l’individualisation de types cliniques. Ann. Med. Psychol. 2008, 5, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desir, M.P.; Karatekin, C. Parental reactions to parent-and sibling-directed aggression within a domestic violence context. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, C.; Condry, R. Adolescent to parent violence: The police response to parents reporting violence from their children. Polic. Soc. 2016, 26, 804–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.; McCrory, E.; Joffe, H.; De Lima, N.; Viding, E. Living with conduct problem youth: Family functioning and parental perceptions of their child. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, J.; Meakings, S. Adolescent-to-parent violence in adoptive families. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 1224–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Howard, J.A.; Monroe, A.D. Issues underlying behaviour problems in at-risk adopted children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2000, 22, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H.; Ford, T.; Goodman, R.; Vostanis, P. The burden of caring for children with emotional or conduct disorders. Int. J. Fam. Med. 2011, 2011, 801203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boxall, H.; Sabol, B. Adolescent family violence: Findings from a group-based analysis. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A.; Birchall, J. ‘Their Mum Messed Up and Gran Can’t Afford to’: Violence towards Grandparent Kinship Carers and the Implications for Social Work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 1231–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, S.E.; Tsermentseli, S.; Papastergiou, A.; Monks, C.P. A Qualitative Exploration of Practitioners’ Understanding of and Response to Child-to-Parent Aggression. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP8274–NP8296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervais, C.; DeCarlo-Slobodnik, D.; Romano, E. Parental Perspectives on Upholding Children’s Rights in the Context of Aggression toward Family/Caregivers in Childhood & Adolescence (AFCCA) in Canada. Can. J. Child. Rights Rev. Can. Droits Enfants 2022, 9, 50–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lyttle, E.; McCafferty, P.; Taylor, B.J. Experiences of adoption disruption: Parents’ perspectives. Child Care Pract. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichail, A.; Bates, E.A. “I want my mum to know that I am a good guy…”: A thematic analysis of the accounts of adolescents who exhibit child-to-parent violence in the United Kingdom. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP6135–NP6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laflamme, E.; Matte-Gagné, C.; Baribeau-Lambert, A. Paternal mind-mindedness and infant-toddler social-emotional problems. Infant Behav. Dev. 2022, 69, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole-Anstey, C.; Townsend, M.L.; Keevers, L. ‘He’s out of control, I’m out of control, it’s just–I’ve got to do something’: A narrative inquiry of child to parent violence. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condry, R.; Miles, C. Children who perpetrate family violence are still children: Understanding and responding to adolescent to parent violence. In Young People Using Family Violence: International Perspectives on Research, Responses and Reforms; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abbaspour, Z.; Vasel, G.; Khojastehmehr, R. Investigating the Lived Experiences of Abused Mothers: A Phenomenological Study. J. Qual. Res. Health Sci. 2021, 10, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, S.; Reeves, E.; Fitz-Gibbon, K. The intergenerational transmission of family violence: Mothers’ perceptions of children’s experiences and use of violence in the home. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2021, 26, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, K. A deeper understanding of child to parent violence (CPV): Personal traits, family context, and parenting. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2021, 0306624X211065588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navas-Martínez, M.J.; Cano-Lozano, M.C. Differential profile of specialist aggressor versus generalist aggressor in child-to-parent violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeza, P.A.I.; Fiscella, J.M.G. Adolescents who are violent toward their parents: An approach to the situation in Chile. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP5678–NP5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Articles | Field | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Badly behaved | [34] | Psychiatry | Fostered child in a therapeutic clinic |

| Behavioural manifestations | [79] | Psychiatry | Clinic case examples |

| Coping or survival behaviours | [85] | Social Work | Adopted children |

| Challenging behaviour | [33,35,40,41,49,51,55,83,84] | Education; Social work; Speech, language and hearing sciences; Psychology | Disabled children and their parents; Parents of adopted children; Parents of preschool children; Community sample of adolescents; Families seeking support for their children’s behaviour |

| Tyrannical behaviour | [80] | Psychiatry | Parents of children with oppositional defiance |

| Disruptive behaviours | [34,50,83] | Psychiatry; Psychiatric nursing; Psychology | Fostered child in therapeutic clinic; Adolescents in treatment for behavioural issues; Community sample of 101 boys and their parents |

| Tantrum-hit sequences | [68] | Clinical psychology | Infants under 2 |

| Psychiatric difficulties | [78] | Psychology | Foster parents |

| Externalising behaviours | [64,68,69,85] | Social work; Clinical psychology | Families with adopted children; Infants under 2 |

| Emotional and behavioural difficulties | [35,78,79,85] | Social work; Psychology; Psychiatry | Parents of adopted children; Foster parents; Child outpatients in a mental health clinic |

| Emotional or behavioural challenges | [55,78] | Psychology | Families seeking support for their children’s behaviour; Foster parents |

| Problem behaviours | [49,64] | Social work; Speech, language and hearing sciences | Families with adopted children; Parents of disabled children |

| Problematic behaviours | [50] | Psychiatric nursing | Families of adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorders |

| Conduct problems | [83] | Psychology | Community sample of 101 boys and their parents |

| Behavioural problems | [53,71,85] | Psychiatry; Social work; Criminology | Parents of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities; Adopted children; Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Behavioural issues | [53] | Criminology | Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Deviant behaviours | [44] | Youth Justice | Youth at a public protection centre |

| Rage | [45,48,85] | Psychiatry; Social work | 9-year-old boy with disability; Records of children hospitalised with mental health issues; Parents of adopted children |

| Anger | [69] | Clinical psychology | Infants under 2 |

| Acts of resistance | [51] | Psychotherapy | Mothers accessing support for their child’s challenging behaviours |

| Adolescent conflict | [64] | Social work | Parents of adopted adolescents |

| Defiance | [68] | Clinical psychology | Infants under 2 |

| Altercations | [50] | Psychiatric nursing | Families of adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorders |

| Aggression | [40,45,51,60,67,72,74,81] | Education; Psychology, Psychotherapy; Psychiatry; Social work; Social psychology | Parents of pre-schoolers; Parents of adopted children; Mothers of 15-year-old adolescents; Mothers in a domestic abuse refuge; Mothers accessing support for their child’s challenging behaviours; 9-year-old boy with disability; Children in mental health outpatient settings; Youth justice settings; Adolescents in secondary school |

| Presenting with aggression | [43] | Psychiatry | 11-year-old autistic boy |

| Children who are aggressive | [84] | Social Work | Parents of adopted children |

| Psychological aggression | [57] | Psychology | School sample |

| Verbal aggression | [41,49,57,72,84,85] | Psychology; Education; Speech, language and hearing sciences; Social work | School sample; Parents of pre-schoolers; Mothers of children with developmental disability (Fragile X); Parents of adopted children; Child mental health outpatients |

| Physical and verbal aggression | [39] | Psychology | Mothers in a domestic abuse refuge |

| Verbal, psychological, and emotional aggression | [46] | Criminal psychology | Practitioners |

| Aggression from children toward parents | [74] | Psychiatry | Mothers of 15-year-old children |

| Verbal, physical, psychological, emotional or financial harm to parents | [54] | Psychology | Families with lived experience |

| Verbal and physical aggression toward mothers | [50,74] | Psychiatry; Psychiatric nursing | Families of adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorders; Mothers of 15-year-old children |

| Physical aggression toward parents and caregivers | [72] | Psychology | Child mental health outpatients |

| Physical altercations with adults | [50] | Psychiatric nursing | Families of adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorders |

| Physical aggression | [41,49,51,68,69,84,85] | Education; Clinical psychology; Speech, language and hearing sciences; Psychotherapy; Social work | Parents of children under 2; Mothers of children with developmental disability (Fragile X); Mothers seeking support for their child’s challenging behaviour; Parents of adopted children |

| Aggressive children | [34,66] | Psychiatry; Criminology | Children in a psychiatric service; 10 individuals from four families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Aggressive behaviour | [43,50,53,66,74,80,84] | Psychiatry; Psychiatric nursing; Social work; Criminology | Parents of children with behavioural ‘disorders’; Mothers of 15-year-old children; Parents of adopted children; Autistic children; Children in a psychiatric service; Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Aggressive outbursts | [43] | Psychiatry | 11-year-old autistic boy |

| Violent outbursts | [53] | Criminology | Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Outbreaks of violence | [48] | Psychiatry | Hospital records of children hospitalised with mental health issues |

| Violent episodes | [48] | Psychiatry | Hospital records of children hospitalised with mental health issues |

| Explosive, irritable or angry | [71] | Psychiatry | Parents of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities |

| Property destruction and abuse | [41] | Education | Parents of pre-schoolers |

| Destructive | [71] | Psychiatry | Parents of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities |

| Explosive, oppositional, and aggressive | [71] | Psychiatry | Parents of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities |

| Explosive, oppositional, and aggressive behaviour | [71] | Psychiatry | Parents of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities |

| Aggressive behaviour toward parents | [48] | Psychiatry | Hospital records of children hospitalised with mental health issues |

| Aggression towards parents | [59,70,73,77,81] | Psychology; Psychosocial; Social work | Mothers in a domestic abuse refuge; Community sample of adolescents; Youth arrested for domestic battery against their mothers |

| Aggression towards others | [40] | Education | Parents of pre-schoolers |

| Aggression towards mothers | [60] | Psychology | Policing data |

| Parent-directed aggression | [39,81] | Psychology | Mothers in a domestic abuse refuge |

| Parent-directed physical aggression | [72] | Psychology | Child mental health outpatients |

| Violence directed against parents | [44] | Youth Justice | Youth at a public protection centre |

| Youth violence directed toward significant others | [65] | Sociology | High school youth and youth referred to a youth justice centre |

| Perpetrates violent acts against their parents | [42] | Law | Practitioner focus groups |

| Crimes against a caregiver | [63] | Psychology | Children and adolescents referred to the Juvenile Court Assessment Centre |

| Youth offenders who use violence against their parents | [76] | Social psychology | Youth involved in youth justice due to violence against parents |

| Violence by adolescents towards their parents | [61] | Psychology | Policing data and community sample of youth |

| Violence against the parent | [48] | Psychiatry | Hospital records of children hospitalised with mental health issues |

| Violence against one’s own parents | [48] | Psychiatry | Hospital records of children hospitalised with mental health issues |

| Violence against parents | [38,65,76] | Psychology; Social psychology; Sociology | Adolescent; High school students; Youth involved in youth justice due to violence against parents |

| Violence towards parents; | [14] | Criminal psychology | Parents experiencing violence |

| Violence directed at parents | [70] | Psychology | Youth in schools |

| Violence towards a parent | [63] | Psychology | Children and adolescents referred to the Juvenile Court Assessment Centre |

| Violence towards their parents | [13] | Criminology | Police data |

| Filial violence | [46] | Criminal psychology | Practitioners |

| Violence | [66] | Psychiatry | Children in psychiatric services |

| Sons’ violence | [60] | Psychology | Police data |

| Violent child | [53] | Criminology | Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Violence from children | [13] | Criminology | Police data |

| Violence from children to parents | [62] | Psychology | Adolescents in secondary school |

| Violence of adolescents toward their parents | [48] | Psychiatry | Medical records of child mental health inpatients |

| Violent behaviour towards parents | [63] | Sociology | High school youth and youth referred to a youth justice centre |

| Violent behaviours against parents | [60] | Psychology | Police data |

| violent behaviour directed by juveniles against members of their own family | [65] | Sociology | High school youth and youth referred to a youth justice centre |

| Violent behaviour | [53,66] | Psychiatry; Criminology | Children in a psychiatric service; Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Violence and destructiveness | [38] | Psychology | Adolescents |

| Adolescent-to-parent violence | [13,36,46,52,75,82,84] | Law; Criminology; Criminal psychology; Social psychology; Social work | Case examples; Police data; Practitioners; Mothers of pre-adolescent children; Parents of adopted children; Community sample |

| Adolescents who are violent towards their family members | [42] | Law | Practitioners |

| Adolescents who are violent towards their parents | [47] | Occupational therapy | Parents and practitioners |

| Adolescent violence to parents | [47] | Occupational therapy | Parents and practitioners |

| Adolescent violence in the home | [47] | Occupational therapy | Parents and practitioners |

| Youth who are violent in the family | [73] | Social Work | Youth arrested for domestic battery against their parent |

| Adolescent-to-parent physical aggression | [77] | Psychology | Adolescents in school |

| Physical and psychological aggressions perpetrated against the mother | [62] | Psychology | Adolescents in school |

| Adolescent-to-mother psychological aggression | [77] | Psychology | Adolescents in school |

| Child-to-mother violence | [47,59,73] | Psychology; Occupational therapy; Social work | Adolescents from a community sample; Parents and practitioners; Youth arrested for domestic battery against their mother |

| Child-to-father violence | [59] | Psychology | Adolescents from a community sample |

| Child-to-parent violence | [13,14,37,46,47,52,54,56,57,60,61,62,63,65,67,70,73,75,76,82,84] | Social work; Sociology; Criminology; Psychology; Social psychology; Criminal psychology; Occupational therapy | Police data; Parent and professional focus groups; Children and adolescent school samples; Parents of children and adolescents instigating this harm; Parents of adopted children; Children and adolescents referred to the Juvenile Court Assessment Centre; Practitioners; Youth arrested for domestic battery against their mothers; Community sample |

| Child-to-parent aggression | [77] | Psychology | Adolescents in school |

| Child-to-parent aggression and violence | [14] | Criminal psychology | Parents of children and adolescents instigating this harm |

| Child-to-parent violence or abuse | [14] | Criminal psychology | Parents of children and adolescents instigating this harm |

| Child-to-parent abuse | [58] | Psychiatry | Adolescent mental health outpatients |

| Parents who are abused by their adolescent children | [74] | Psychiatry | Mothers of 15-year-old children |

| Parent abuse | [39,46,47,58,60,61,72,79,81,82] | Psychiatry; Psychology; Criminal psychology; Criminology; Occupational therapy | Clinic case examples; Child and adolescent mental health outpatients; Mothers in a domestic abuse refuge; Parents; Practitioners; Policing data |

| Mother abuse | [47,84] | Occupational therapy; Social work | Parents and practitioners; Parents of adopted children |

| Adolescent abuse towards parents | [47] | Occupational therapy | Parents and practitioners |

| Adolescents who assaulted their parents | [37] | Psychology | Parent and professional focus groups |

| Juveniles who assault their parents | [61] | Psychology | Policing data and community sample of youth |

| Parental maltreatment | [74] | Psychiatry | Mothers of 15-year-old children |

| Abused parents | [79] | Psychiatry | Clinic case examples |

| Abuse of parents | [37] | Psychology | Focus group of parents and practitioners |

| Abuse | [14,36,42,54,57,60,78] | Law; Psychology; Criminal psychology | Case examples; Foster parents; School sample; Professional focus groups; Parents of children and adolescents instigating this harm; Policing data |

| Abusing | [42] | Law | Practitioners |

| Verbal and Physical Abuse Toward Mothers | [74] | Psychiatry | Mothers of 15-year-old children |

| Physical abuse | [53,79,80] | Psychiatry; Criminology | Clinic case examples; Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Verbal abuse | [53,79] | Psychiatry; Criminology | Clinic case examples; Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Abusive children | [79] | Psychiatry | Clinic case examples |

| Abusive behaviour | [53] | Criminology | Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Abusive behaviour towards mothers | [74] | Psychiatry | Mothers of 15-year-old children |

| Abusive actions perpetrated by children and adolescents towards their parents | [54] | Psychology | Families with lived experience |

| Violent abusers | [42] | Law | Practitioners |

| Youth who perpetrate violence against a parent | [73] | Social Work | Youth arrested for domestic battery against their mother |

| Violence perpetrated by children against their parents | [48] | Psychiatry | Medical records of child mental health inpatients |

| Violence and abuse perpetrated against parents | [82] | Criminology | Policing data |

| Adolescent family violence | [42,47] | Law; Occupational therapy | Parents; Practitioners |

| Family Violence | [44,59] | Youth Justice; Psychology | Youth at a public protection centre; Adolescents |

| Intrafamily violence | [48,59] | Psychology; Psychiatry | Adolescents; Medical records of child mental health inpatients |

| Domestic violence incident | [56] | Criminology | Policing data |

| Physical violence | [75] | Social psychology | Community sample of adolescents |

| Psychological violence | [75] | Social psychology | Community sample of adolescents |

| Coercive behaviour | [64] | Social work | Parents of adopted adolescents |

| Violent, controlling and coercive behaviours | [84] | Social Work | Parents of adopted children |

| Controlling behaviours | [84] | Social Work | Parents of adopted children |

| Psychological control | [80] | Psychiatry | Parents of children with oppositional defiance |

| Violence | [53,84] | Social Work; Criminology | Parents of adopted children; Families who self-reported living with a child with mental illness |

| Harm | [46] | Criminal psychology | Practitioners |

| Harmful act by an adolescent against a parent | [73] | Social Work | Youth arrested for domestic battery against their mother |

| Non-homicidal physical attacks | [79] | Psychiatry | Clinic examples |

| Physically assaulting parents | [57] | Psychology | School sample |

| Parent battering | [48] | Psychiatry | Medical records of child mental health inpatients |

| Children who batter their parents | [74] | Psychiatry | Mothers of 15-year-old children |

| Battered parent syndrome | [48,80,82] | Psychiatry; Criminology | Parents of children with oppositional defiance; Medical records of child mental health inpatients; Police data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rutter, N. “My [Search Strategies] Keep Missing You”: A Scoping Review to Map Child-to-Parent Violence in Childhood Aggression Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054176

Rutter N. “My [Search Strategies] Keep Missing You”: A Scoping Review to Map Child-to-Parent Violence in Childhood Aggression Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054176

Chicago/Turabian StyleRutter, Nikki. 2023. "“My [Search Strategies] Keep Missing You”: A Scoping Review to Map Child-to-Parent Violence in Childhood Aggression Literature" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054176

APA StyleRutter, N. (2023). “My [Search Strategies] Keep Missing You”: A Scoping Review to Map Child-to-Parent Violence in Childhood Aggression Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054176