Nonresponsive Parenting Feeding Styles and Practices and Risk of Overweight and Obesity among Chinese Children Living Outside Mainland China: An Integrative Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Data Synthesis

2.4. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

3. Results

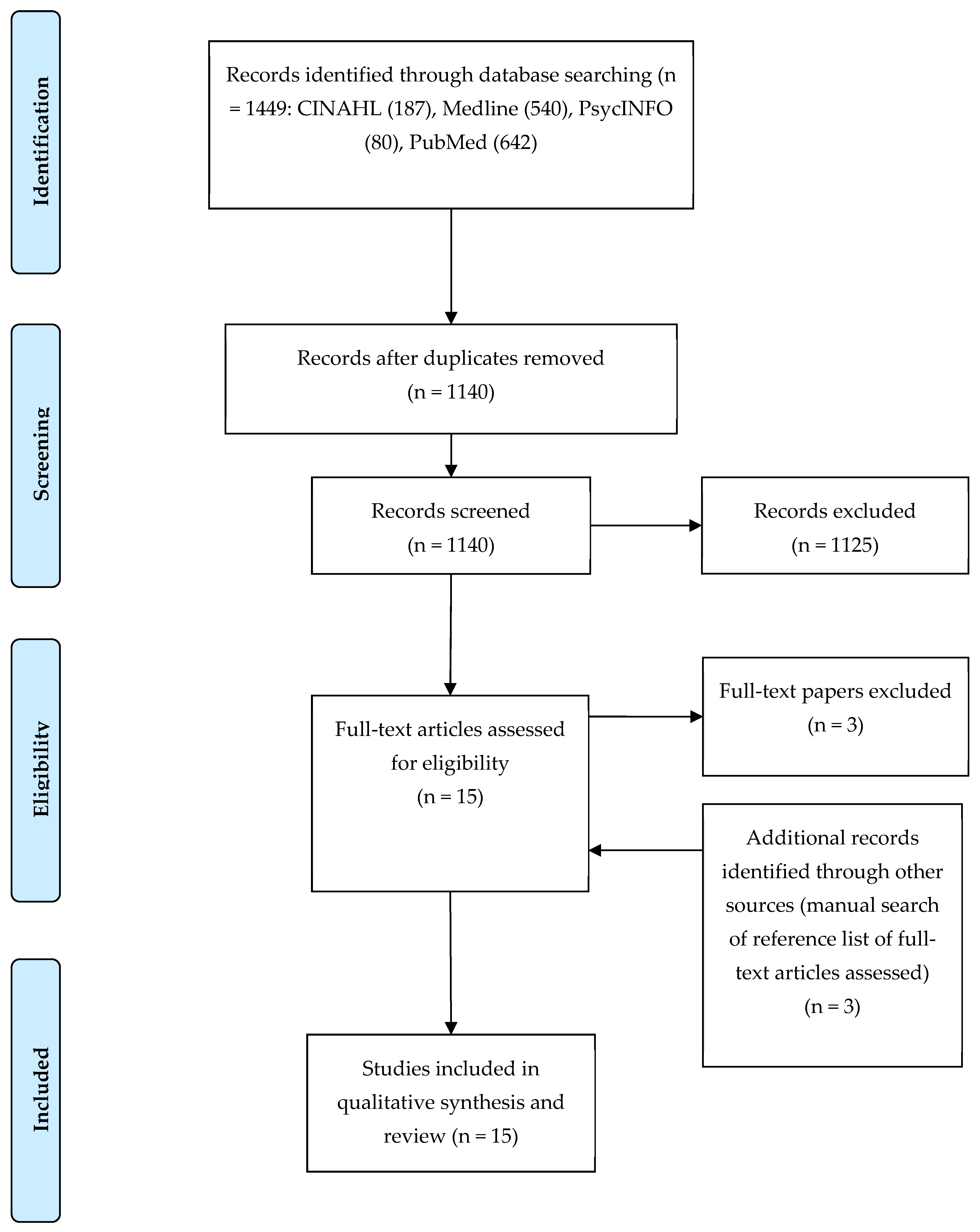

3.1. Search

3.2. Summary of Included Studies

3.3. Studies of Pre-School-Age Children Only

3.3.1. Parenting Feeding Styles

3.3.2. Parenting Feeding Practices

3.4. Studies with School-Age Children Only

3.4.1. Parenting Feeding Styles

3.4.2. Parenting Feeding Practices

3.5. Studies including Both Pre-School and School-Age Children

Parenting Feeding Practices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoeffel, E.; Porter, S.; Kim, M.; Shahid, H. The Asian Population: 2010: 2010 Census Briefs. 2018. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2012/dec/c2010br-11.html (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Lv, N.; Brown, J.L. Chinese American Family Food Systems: Impact of Western Influences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, S.Y.; Beasley, J.M.; Kwon, S.C.; Huang, K.-Y.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Acculturation and activity behaviors in Chinese American immigrants in New York City. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 404–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Curtin, L.R.; McDowell, M.A.; Tabak, C.J.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006, 295, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantino, R. Addressing childhood and adolescent overweight. In Proceedings of the the NICOS Meeting of the Chinese Health Coalition, San Francisco, CA, USA, September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Monteiro, C.; Popkin, B.M. Trends of obesity and underweight in older children and adolescents in the United States, Brazil, China, and Russia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.S.; Wang, J.; Thornton, J.C.; Mei, Z.; Pierson, R.N.; Dietz, W.H.; Horlick, M. Racial/ethnic Differences in Body Fatness Among Children and Adolescents. Obesity 2008, 16, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navder, K.P.; He, Q.; Zhang, X.; He, S.; Gong, L.; Sun, Y.; Deckelbaum, R.J.; Thornton, J.; Gallagher, D. Relationship between body mass index and adiposity in prepubertal children: Ethnic and geographic comparisons between New York City and Jinan City (China). J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.P.; David Cheng, T.Y.; Tsai, S.P.; Chan, H.T.; Hsu, H.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Eriksen, M.P. Are Asians at greater mortality risks for being overweight than Caucasians? Redefining obesity for Asians. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, F.; Anand, S.S.; Shannon, H.; Vuksan, V.; Davis, B.; Jacobs, R.; Teo, K.K.; McQueen, M.; Yusuf, S. Defining obesity cut points in a multiethnic population. Circulation 2007, 115, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Sussner, K.M.; Kim, J.; Gortmaker, S. The Role of Parents in Preventing Childhood Obesity. Future Child. 2006, 16, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleddens, E.F.C.; Gerards, S.M.P.L.; Thijs, C.; de Vries, N.K.; Kremers, S.P.J. General parenting, childhood overweight and obesity-inducing behaviors: A review. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, e12–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, A.K.; Birch, L.L. Does parenting affect children’s eating and weight status? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, L.; Cooke, L.; Hill, C.; Wardle, J. Child adiposity and maternal feeding practices: A longitudinal analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. Handb. Child Psychol. 1983, 4, 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Blissett, J. Relationships between parenting style, feeding style and feeding practices and fruit and vegetable consumption in early childhood. Appetite 2011, 57, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, S.O.; Power, T.G.; Orlet Fisher, J.; Mueller, S.; Nicklas, T.A. Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite 2005, 44, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.O.; Grimm-Thomas, K.; Markey, C.N.; Sawyer, R.; Johnson, S.L. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 2001, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiese, B.H.; Foley, K.P.; Spagnola, M. Routine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: Contexts for child well-being and family identity. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2006, 2006, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.; Marwaha, R. Developmental Stages of Social Emotional Development in Children; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Hughes, S.O.; Watson, K.B.; Baranowski, T.; Nicklas, T.A.; Fisher, J.O.; Beltran, A.; Baranowski, J.C.; Qu, H.; Shewchuk, R.M. Parenting practices are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.; Nicklas, T.A.; Hughes, S.O.; Morales, M. The benefits of authoritative feeding style: Caregiver feeding styles and children’s food consumption patterns. Appetite 2005, 44, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevers, D.W.M.; Kremers, S.P.J.; de Vries, N.K.; van Assema, P. Clarifying concepts of food parenting practices. A Delphi study with an application to snacking behavior. Appetite 2014, 79, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shloim, N.; Edelson, L.R.; Martin, N.; Hetherington, M.M. Parenting styles, feeding styles, feeding practices, and weight status in 4–12 year-old children: A systematic review of the literature. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; He, Y.; Fang, Y. Status of parents’ feeding behavior and influencing factors in 3–5 years old children in 5 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities) of China in 2018. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2020, 49, 208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-L.; Yang, J.; Wang, D.; Wu, P.-P.; Xian, Y.-J. Current status of parental feeding behaviors in Urumqi, China, and its association with body mass index of children. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2018, 20, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Ma, Y.; Hu, J.; Lin, W.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, D. Predicting weight status in Chinese pre-school children: Independent and interactive effects of caregiver types and feeding styles. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xu, T.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Z.; Yu, L.; Jiang, X.; Shang, L. Correlation between Children’s eating behaviors and caregivers’ feeding behaviors among preschool children in China. Appetite 2019, 138, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Wang, G.; Tan, T.X. Mothers’ feeding profiles among overweight, normal weight and underweight Chinese preschoolers. Appetite 2020, 152, 104726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Rosenqvist, U.; Wang, H.; Greiner, T.; Ma, Y.; Michael Toschke, A. Risk factors for overweight in 2- to 6-year-old children in Beijing, China. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2006, 1, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-L.; Kennedy, C. Factors associated with obesity in Chinese-American children. Pediatr. Nurs. 2005, 31, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.H.; Parks, E.P.; Kumanyika, S.K.; Grier, S.A.; Shults, J.; Stallings, V.A.; Stettler, N. Child-feeding practices among Chinese-American and non-Hispanic white caregivers. Appetite 2012, 58, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, D.; Bauer, K.D. Exploratory Investigation of Obesity Risk and Prevention in Chinese Americans. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2007, 39, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, H.-L.; Contento, I. Parental perceptions, feeding practices, feeding styles, and level of acculturation of Chinese Americans in relation to their school-age child’s weight status. Appetite 2014, 80, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Benton, L. The association of acculturation and complementary infant and young child feeding practices among new chinese immigrant mothers in England: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, e78–e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy: The Matrix Method, 3rd ed.; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (CASP), C.A.S.P. Qualitative Research: Appraisal Tool Public Health Resource Unit; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Korani, M.; Rea, D.M.; King, P.F.; Brown, A.E. Significant differences in maternal child--feeding style between ethnic groups in the UK: The role of deprivation and parenting styles. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.S.L.; Van Hook, J. Chinese and Korean immigrants’ early life deprivation: An important factor for child feeding practices and children’s body weight in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomitz, V.R.; Brown, A.; Lee, V.; Must, A.; Chui, K.K.H. Healthy Living Behaviors Among Chinese–American Preschool-Age Children: Results of a Parent Survey. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 20, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.Y.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Fierman, A.H.; Au, L.Y.; Messito, M.J. Perception of Child Weight and Feeding Styles in Parents of Chinese-American Preschoolers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Warkentin, S.; Jansen, E.; Carnell, S. Acculturation, food-related and general parenting, and body weight in Chinese-American children. Appetite 2022, 168, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-H.; Mallan, K.M.; Mihrshahi, S.; Daniels, L.A. Feeding beliefs and practices of Chinese immigrant mothers. Validation of a modified version of the Child Feeding Questionnaire. Appetite 2014, 80, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, K.; Cheung, C.; Lee, A.; Tam, W.W.S.; Keung, V. Associations between parental feeding styles and Childhood eating habits: A survey of Hong Kong pre-school children. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, K.T.T.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Sun, S.; Zhou, N.; Xue, X. Adaptation and assessment of the Child Feeding Questionnaire for Chinese immigrant families of young children in the United States. Child Care Health Dev. 2020, 46, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.; Tsang, S.; Lo, S.K.; Chan, R. Family mealtime environment and child behavior outcomes in Chinese preschool children. Int. J. Child Health Hum. Dev. 2018, 11, 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Sobko, T.; Jia, Z.; Kaplan, M.; Lee, A.; Tseng, C.-H. Promoting healthy eating and active playtime by connecting to nature families with preschool children: Evaluation of pilot study “play&Grow”. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 81, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.-J.; Yeh, M.-C. Parenting style and child-feeding behaviour in predicting children’s weight status change in Taiwan. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 17, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Van Hook, J.; Thompson, D.A.; Jones, S.S. A cultural understanding of Chinese immigrant mothers’ feeding practices. A qualitative study. Appetite 2015, 87, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, L.A.; O’Connor, T.M.; Chen, T.-A.; Nicklas, T.; Power, T.G.; Hughes, S.O. Parents’ perceptions of preschool children’s ability to regulate eating. Feeding style differences. Appetite 2014, 76, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.O.; Power, T.G.; Papaioannou, M.A.; Cross, M.B.; Nicklas, T.A.; Hall, S.K.; Shewchuk, R.M. Emotional climate, feeding practices, and feeding styles: An observational analysis of the dinner meal in Head Start families. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, E.; Hughes, S.O.; Goldberg, J.P.; Hyatt, R.R.; Economos, C.D. Parent behavior and child weight status among a diverse group of underserved rural families. Appetite 2010, 54, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, G.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Oenema, A.; van de Mheen, D. Psychological control by parents is associated with a higher child weight. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, K.; Andrianopoulos, N.; Hesketh, K.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Brennan, L.; Corsini, N.; Timperio, A. Parental use of restrictive feeding practices and child BMI z-score. A 3-year prospective cohort study. Appetite 2010, 55, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.C.; Kolko, R.P.; Stein, R.I.; Welch, R.R.; Perri, M.G.; Schechtman, K.B.; Saelens, B.E.; Epstein, L.H.; Wilfley, D.E. Modifications in parent feeding practices and child diet during family--based behavioral treatment improve child zBMI. Obesity 2014, 22, E119–E126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Sutin, A.R. Parental perception of weight status and weight gain across childhood. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, L.M.; Galuska, D.A.; Blanck, H.M.; Serdula, M.K. Maternal perceptions of weight status of children. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, L.; Hill, C.; Cooke, L.; Carnell, S.; Wardle, J. Associations between child weight and maternal feeding styles are mediated by maternal perceptions and concerns. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Chen, Y.; Kellow, N.J.; Choi, T.S.T. Exploring the Determinants of Food Choice in Chinese Mainlanders and Chinese Immigrants: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items: | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1. Is the study longitudinal? | ||||||||||

| #2. Does the paper describe the participants’ eligibility criteria? | ||||||||||

| #3. Were study participants randomly selected (or representative of the study population)? | ||||||||||

| #4. Did the paper report information about the measures, including references used to assess parental feeding practices? | ||||||||||

| #5. Did the study include information on instrument or scale used to assess parental feeding practices that have acceptable reliability? | ||||||||||

| #6. Did the study provide information power calculation to detect hypothesized relationships? | ||||||||||

| #7. Did the study report the number of individuals who completed each of the different measures? | ||||||||||

| #8. Did the participants/respondents complete at least 80% of measures? | ||||||||||

| #9. Did analyses take into account confounding factors? | ||||||||||

| Items | ||||||||||

| Studies | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 | #6 | #7 | #8 | #9 | Total |

| Korani et al. [41] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Cheah et al. [42] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Chen et al. [31] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Chomitz et al. [43] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Huang et al. [32] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Pai et al. [34] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Chang et al. [44] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Gu et al. [45] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Liu et al. [46] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Lo et al. [47] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Vu et al. [48] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Leung et al. [49] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Sobko et al. [50] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Tung et al. [51] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Qualitative Evaluation Criteria | Zhou et al. 2014 [52] |

|---|---|

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Yes |

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Yes |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? (e.g., How were participants selected? e.g., purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball?; How were participants approached? e.g., face-to-face, telephone, mail, email?) | Yes |

| Were data collected in a way appropriate to address the research questions? (e.g., Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? Was data saturation discussed?) | Yes |

| Was the relationship between researcher and participants considered? | No |

| Were ethical issues taken into consideration? | Yes |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes |

| Is there a clear statement of findings? | Yes |

| Is the research valuable? | Yes |

| Characteristics | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| Eligible studies | 15 |

| Publication dates | |

| 2000–2007 | 1 |

| 2008–2014 | 5 |

| 2015–2022 | 9 |

| Research methods (study design) | |

| Qualitative | 1 |

| Quantitative (cross-sectional) | 11 |

| Quantitative (longitudinal) | 3 |

| Countries/Regions represented | |

| United States | 9 |

| Hong Kong | 3 |

| Australia | 1 |

| Taiwan | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 1 |

| Focus | |

| Feeding practices | 8 |

| Feeding practices and styles | 5 |

| Feeding styles | 2 |

| Authors, Year Country | Sample Characteristics and Study Design | Study Aim (s) | Measures | Main Findings Related to Parenting Feeding Styles and Practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Study | ||||

| Zhou et al. [52], 2015 U.S. | n = 22 Immigrant mothers. Mothers’ age range: 34–49 years. Children’s age range: 3–5 years. Qualitative design. | To identify whether parental feeding practices among Chinese mothers are similar to those identified in studies of European-origin families, as well as feeding practices that appear to be culturally emphasized or unique. | Focus group discussions. Open-ended questions with prompts designed to explore parental feeding practices regarding: (a) the important issues in their feeding, (b) how mothers made sure their children ate the types of foods they wanted them to eat, and (c) how mothers got their child to eat the right amount of food. | Thirteen key themes: nine known feeding practices and four culturally emphasized practices were identified. Pre-existing feeding practices included control, pressuring, restriction, use of food as reward and punishment, monitoring food intake (type and amount), and encouraging healthy eating. Culturally emphasized feeding practices included regulating healthy routines and food intake, spoon-feeding, using social comparison to pressure the child to eat, and making an effort to prepare/cook specific foods. |

| Quantitative Studies | ||||

| Study Sample Limited to Parents of Pre-school-age Children Only | ||||

| Liu et al. [46], 2014 Australia | n = 254 Chinese immigrant mothers who had lived in in Australia for less than 10 years. Mothers’ age range: 24–47 years. Children’s age range: 1–4 years. Cross-sectional. | To evaluate: (1) the psychometric properties and factor structure of a modified version of the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) and (2) the association between the CFQ factors in the ‘best-fitting’ model and children’s weight status. | Modified CFQ | The use of food rewards and restrictions appeared to have different influences on child health outcomes. Mothers’ feeding beliefs and perceptions of feeding responsibility were positively associated with feeding practices such as restriction, pressuring children to eat, monitoring children’s food intake, and using food rewards. Mothers’ concern about children becoming overweight was not associated with any assessed feeding practices. Mothers had high levels of perceived feeding responsibility and low levels of concern; however, these were associated with their children’s weight status. Restriction and use of food rewards were not associated with children’s weight status reported by parents. Pressuring children to eat was negatively associated with children’s weight status. Mothers who perceived their children as ‘thin’ were more likely to pressure them to eat. |

| Lo et al. [47], (2015) Hong Kong | n = 4553 Chinse immigrant mothers and fathers. Parents’ age is unclear. Children’s age range: 2–5 years. Cross-sectional. | To investigate the association between parental feeding styles and dietary intake among pre-school students in Hong Kong. | Parental Feeding Style Questionnaire (PFSQ) | Instrumental and emotional feeding styles were associated with unhealthy dietary patterns such as inadequate consumption of fruit, vegetables, and breakfast. They also was positively correlated with the intake of high-energy-density food. Encouraging children to eat was associated with more frequent consumption of fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and breakfast. ‘Control over child eating’ correlated with children more frequently consuming fruits, vegetables and breakfast, as well as less consumption of dairy products and high-energy-density food. |

| Chang et al. [44], (2017) U.S. | n = 253 Chinese immigrant mothers and fathers. Parents’ mean age: 32.7 ± 5.4 years. Children’s age range: 24–59 months. Cross-sectional. | To examine the associations between controlling feeding style, parent perception of child’s weight, and gender in Chinese families with young children. | Parent feeding style was assessed using the restriction factor (eight questions) and the pressuring factor (four questions) derived from the CFQ. Parent’s perception of child weight was assessed using a question adapted from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Child height and weight were obtained through review of the medical record. | Parents’ underperception of child weight was common but more likely in boys than girls. The mean pressuring and restriction scores were high, suggesting an endorsement of both styles for the overall sample. Parents were more likely to pressure boys than girls to eat. Parents’ pressure to eat did not vary significantly with their perception of their children’s weight status. However, pressure to eat was lower for girls perceived as overweight than those perceived as normal or underweight. Restrictive feeding style was not associated with parents’ perception of children’s weight, gender, or actual weight status. |

| Chomitz et al. [43], (2017) U.S. | n = 132 Chinese immigrant mothers and fathers. Parents’ age unclear. Children’s age range: 3.5–6.0 years. Cross-sectional. | To describe results from a community-initiated needs assessment of the eating and active living behaviors of pre-school-age Asian children in Chinatown-based early education and care programs, as well as the parenting styles of the parents/caregivers who completed the survey. | Thirteen adapted items were used to characterize three parenting practices associated with healthy eating and obesity, such as appropriate attention to hunger and satiety cues and authoritative, indulgent, or permissive styles. | Parenting practices such as control and restriction known to be associated with the risk of obesity were apparent. Although healthy-living behavioral outcomes were less prevalent among less acculturated parents, multivariable adjustment attenuated the observed significant differences. |

| Sobko et al. [50] (2017) Hong Kong | n = 38 Chinese immigrant mothers and their female domestic helpers. Mothers’ mean age: 36.76 ± 4.00 years. Domestic helpers’ mean age: 35.84 ± 7.26 years. Children’s age range: 2–4 years. Pilot intervention. | To test if intervention activities promote positive changes in caregivers’ feeding practices and eating habits in pre-school children. | PFSQ Hong Kong Children’s Dietary Habit Questionnaire (HKCDHQ). | Feeding practices, particularly promoting and encouraging children to eat and instrumental feeding improved after the intervention. Domestic helpers’ responsibility for children’s cooking and instrumental feeding practices predicted children’s picky eating. |

| Leung et al. [49] (2018) Hong Kong | n = 470 Chinese immigrant mothers and fathers. Mothers’ mean age: 34.5 ± 5.27 years. Fathers’ mean age: 38.5 ± 6.82 years. Children’s age range: 3–6 years. Longitudinal. | To examine the influence of family mealtime environment, parenting styles, and family functioning on children’s behavior. | Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ). Chinese Family Assessment Instrument (C-FAI). HKPFQ. | A higher frequency of child behavioral problems was associated with more authoritarian and permissive parenting styles, less healthy feeding practices, and the child being male. Family feeding practice was a mediator between permissive/authoritarian parenting and frequency of child behavior problems. |

| Pre-school and School-Age Children | ||||

| Cheah et al. [42] (2012) United States | n = 81 Chinese immigrant parents. Mothers and fathers. Mothers’ age range: 32–51 years. Fathers’ age range: 28–52 years. Children’s age range: 3–8 years. Cross-sectional. | To explore the relationships between Chinese immigrant and non-White Hispanic parents’ early life material and food deprivation and (1) concern about their child’s diet or weight; (2) preferences for plumpness; and (3) weight-promoting diet and outcomes. | CFQ | Parents’ early life food insecurity was associated with the evaluation that their child should weigh more than they do and children’s greater consumption of soda and sweets among the least acculturated parents. Parental material deprivation was associated with more laissez-faire child feeding practices: less monitoring, less concern about the child’s weight or diet, and less perceived responsibility for the child’s diet, but only among less acculturated parents. Immigrant parents’ child feeding practices and body size evaluations were shaped by material hardship in childhood, but these influences may fade as acculturation occurs. |

| Huang et al. [32] (2012) United States | n = 50 Chinese immigrant and Chinese-American mothers. Mothers only. Mothers’ age: unclear. Children’s age range: 2–12 years. Cross-sectional. | To gain a better understanding of attitudes, beliefs, and child feeding practices in Chinese-Americans and to explore these practices in relation to obesity risk. | CFQ | Findings determined that Chinese-American mothers had higher mean scores of concerns and restriction in all age groups and monitoring than non-Hispanic white mothers. No feeding practices were associated with child BMI in Chinese-Americanss. |

| Vu et al. [48], (2020) United States | n = 216 Mothers only. Mothers’ mean age: 38.31 ± 4.34 years. Children’s age range: 2.40–9.54 years. Cross-sectional. | To examine the underlying factor structure of the original CFQ (7-factor model) and the modified CFQ with additional Asian cultural-specific feeding items (eight- and nine-factor model). The validity if the CFQ among U.S. Chinese immigrant mothers also was examined. | CFQ | The nine-factor model, which included cultural-specific feeding items, was the most optimal model to represent the factor structure of feeding beliefs and practices among Chinese immigrant mothers of young children in the U.S. Mothers’ feeding beliefs and practices were associated with children’s and mothers’ BMI and mothers’ perceptions of their children’s body size. |

| Study Sample Limited to Parents of School-Age Children Only | ||||

| Chen et al. [31], (2005) United States | n = 68 Chinese immigrant mothers. Mothers’ mean age: 42.09 ± 3.81 years. Children’s age range: 8–10 years. Cross-sectional. | To examine factors associated with obesity in Chinese-American children. | Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). | Three variables predicted children’s BMI, older age, a more democratic parenting style, and poor communication. Children whose mothers had a low level of acculturation were more likely to be overweight than children whose mothers were highly acculturated. |

| Pai et al. [34], (2014) United States | n = 712 Chinese immigrant mothers. Mothers’ age range: 25–56 years. Children’s age range: 5–10 years. Cross-sectional. | To explore the relationships between parental perceptions, feeding practices, feeding styles, parental acculturation, and child weight status. | CFQ and the Caregiver’s Feeding Styles Questionnaire (CFSQ). | Level of maternal acculturation was not directly predictive of child overweight. Chinese-American mothers tended to use indulgent (33.2%) and authoritarian (27.9%) feeding styles, with the former increasing with greater acculturation and the latter decreasing. Indulgent mothers were more likely to have more overweight and obese children, and authoritarian and authoritative parents fewer. Level of maternal acculturation was negatively predictive of pressure to eat healthy foods, which was negatively correlated with child weight status. Level of maternal acculturation was positively correlated with responsiveness to child needs, monitoring of child intake, and perceived responsibility for child feeding. |

| Tung et al. [51], (2014) Taiwan | n = 465 mother-child dyad. Mothers’ mean age: 37.05 ± 4.19 years for boys, 37.03 ± 4.95 years for girls. Children’s mean age: 8.45 ± 1.03 years for boys, 8.35 ± 1.02 years for girls at baseline. Longitudinal. | To examine the associations between child feeding practices and weight status changes over 1 year among a sample of school-age children in Taiwan. | PSDQ CFQ | Controlling for baseline weight status revealed moderating effects of parenting style on the relationship between child feeding practices and child weight status. Two feeding practices, concerning child weight and monitoring, were significant predictors of child overweight status among children with authoritative mothers. Mothers with a stronger perceived responsibility for child feeding also scored higher on pressure to eat and monitor. Mothers who were concerned about their daughter’s weight status employes feeding practices involving more restriction of food and less pressure to eat. Parents’ perpetion of their children’s weight and concern about child weight increased from children’s underweight to obesity. Parents with underweight children used more pressure to eat than those with overweight children. |

| Korani et al. [41], (2018) United Kingdom | n = 84 Chinese immigrant mothers. Mothers only. Mother’s age range: 23–54 years. Children’s age range: 5–11 years. Cross-sectional. | To explore variations in maternal child-feeding style between ethnic groups in the U.K., considering associated factors such as deprivation and parenting style. | CFQ PFSQ PSDQ | Significant differences in perceived responsibility, restriction, pressure to eat, instrumental feeding, and emotional feeding were found between the groups. Mothers from Chinese backgrounds reported greater perceived responsibility and use of restriction. Maternal child-feeding style was associated with deprivation and parenting style. |

| Gu et al. [45], (2022) United States | n = 233 Chinese-American parents. Mothers and fathers. Parents’ mean age: 42.4 ± 5.5 years. Children’s age range: 5–12 years. Cross-sectional. | To investigate associations of acculturation with parents’ food-related parenting and general parenting behaviors in a sample of predominantly first-generation immigrant Chinese-American parents of school-age children. To test associations of parent feeding and general parenting behaviors with child body mass index z-score in this sample, based on parent-report data of child height and weight. | CFQ PFSQ CFSQ PSDQ | Acculturation was associated with higher scores on responsiveness in feeding, lower scores on subscales assessing controlling feeding behaviors, lower scores on nonnutritive feeding behaviors, and a greater likelihood of indulgent feeding styles. Acculturation was associated with lower scores on subscales assessing authoritarian parenting. Parental prompting/encouragement to eat was associated with a lower child BMI z-score, while authoritarian parenting subscales were associated with a higher BMI z-score. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, Q.; Greaney, M.L.; Lindsay, A.C. Nonresponsive Parenting Feeding Styles and Practices and Risk of Overweight and Obesity among Chinese Children Living Outside Mainland China: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054090

Le Q, Greaney ML, Lindsay AC. Nonresponsive Parenting Feeding Styles and Practices and Risk of Overweight and Obesity among Chinese Children Living Outside Mainland China: An Integrative Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054090

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Qun, Mary L. Greaney, and Ana Cristina Lindsay. 2023. "Nonresponsive Parenting Feeding Styles and Practices and Risk of Overweight and Obesity among Chinese Children Living Outside Mainland China: An Integrative Review of the Literature" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054090

APA StyleLe, Q., Greaney, M. L., & Lindsay, A. C. (2023). Nonresponsive Parenting Feeding Styles and Practices and Risk of Overweight and Obesity among Chinese Children Living Outside Mainland China: An Integrative Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054090