Partnerships at the Interface of Education and Mental Health Services: The Utilisation and Acceptability of the Provision of Specialist Liaison and Teacher Skills Training

Abstract

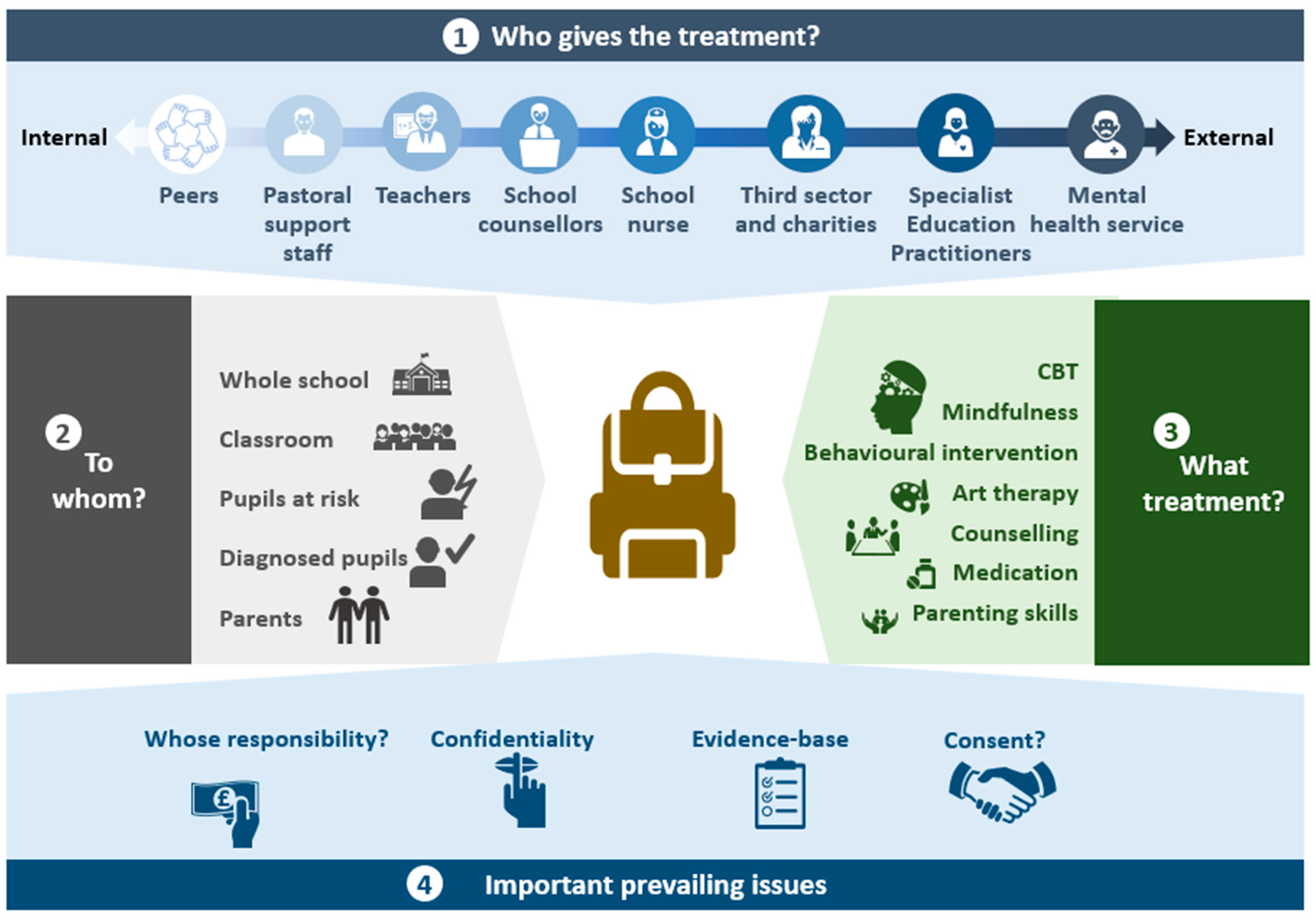

1. Introduction

2. Project 1: Mental Health Service Liaison to School Staff—The InReach Programme

2.1. Intervention Description

2.2. Participating Schools

2.3. Outcome Assessment

2.4. Key Learning

2.5. Implications for Practice

- The liaison service was most commonly used as a consultation and advice service for school staff members, followed by individual and group work with students.

- Emotional difficulties, particularly anxiety, was the most common area of need discussed with the mental health professionals.

- The mental health professionals perceived several potential benefits of the service, most notably in terms of providing timely advice, giving needed support in how to manage students within the school setting, assisting with safeguarding concerns, and improving communication with formal mental health services.

3. Project 2: Mental Health Skills Training for School Staff—The School Mental Health Toolbox (SMHT)

3.1. Intervention Description

- Sleep hygiene: teaching the principles of good sleep in relation to the environment, the awareness of activities and food that can act as stimulants interfering with sleep, and the importance of maintaining a regular circadian rhythm.

- Behavioural change to address mood and/or anxiety difficulties: identifying and supporting behaviour changes in students who are becoming withdrawn from usual activities.

- Relaxation techniques: three different relaxation techniques described, namely, deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and the ‘peaceful scene’.

- Addressing potential social isolation by better understanding students’ current networks of support using a ‘map’. This aims to help students appreciate that there can be a number of different individuals whom they may call upon when they become distressed and that they might not be as isolated as they perceive themselves to be. The map can also highlight areas where it may be useful to build additional support.

- A ‘treasure box’ of how students can help themselves in difficult situations. This is tailored to each specific individual and their problems, but it has the general aim of showing them that they have the capacity to help themselves when they are in distress or difficulty.

- How to approach students who have experienced traumatic events: this focuses on psychoeducation and learning about the importance of referral to specialist services and how to support students in that process.

- Problem-solving techniques (time permitting): this draws upon collaborative problem-solving approaches and follows a number of pre-defined steps with an emphasis on identifying solutions.

3.2. Participating Schools

3.3. Outcome Assessment

3.4. Key Learning

3.5. Implications for Practice

- Three months after participating in a mental health skills training programme, 85% reported having used the skills learned during the training with a student.

- The most ‘popular’ skills in terms of post-training use were the relaxation techniques and sleep advice.

- Skills were most commonly used to support students with emotional and behavioural difficulties, though many staff also found them useful for their own mental health and wellbeing.

- Nearly all staff found the training at least moderately helpful, and most would recommend it to their colleagues.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Partnership Working—A Feasible Solution for a Well-Documented Need

4.3. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

- How do school staff perceive mental health liaison services? Although we had originally planned to interview school staff regarding their experiences of the InReach programme, this was not possible due to the disruptions of the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst the InReach workers perceived many possible benefits of their work, it is critical to know how the service was viewed by school staff.

- What were school staff’s experiences of using the SMHT tools, and what were students’ experiences of them? Understanding the implementation drivers associated with the training goes beyond whether school staff used the tools; in addition, it is important to understand the perceived and actual mental health impact of the tools from the point of view of those delivering them (school staff) and receiving them (students).

- What do CAMHS workers and school staff members perceive as the barriers and facilitators of partnership working? Further qualitative research can help better understand how best to design, implement, and evaluate the impact of partnership working.

- Does partnership working improve school staff members’ confidence and preparedness for addressing student mental health difficulties? As the main aim of these services was to support school staff, it is important to understand the impact on staff attitudes and self-efficacy towards student mental health. Gathering data on the existing skills of the staff prior to training would help to understand any differential impacts of additional training.

- Is partnership working associated with improved mental health outcomes for students? As we designed these studies as pilot projects, we did not include any mental health outcomes for students. Well-designed, adequately powered studies are needed to understand the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of these strategies.

- Is partnership working associated with improved school climate and home environment? It would be important to find ways to measure the broader systemic impacts of work conducted in schools and how this might impact the general experience of children within both the classroom and other school activities, as well as if there are impacts on families, including on parents and siblings.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fazel, M.; Hoagwood, K.; Stephan, S.; Ford, T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, J.R.; Southam-Gerow, M.A.; Gordis, E.B.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Chu, B.C.; Langer, D.A.; McLeod, B.D.; Jensen-Doss, A.; Updegraff, A.; Weiss, B. Cognitive–behavioral therapy versus usual clinical care for youth depression: An initial test of transportability to community clinics and clinicians. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallard, P.; Skryabina, E.; Taylor, G.; Phillips, R.; Daniels, H.; Anderson, R.; Simpson, N. Classroom-based cognitive behaviour therapy (FRIENDS): A cluster randomised controlled trial to Prevent Anxiety in Children through Education in Schools (PACES). Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geulayov, G.; Borschmann, R.; Mansfield, K.L.; Hawton, K.; Moran, P.; Fazel, M. Utilization and acceptability of formal and informal support for adolescents following self-harm before and during the first COVID-19 lockdown: Results from a large-scale English schools survey. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 881248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, T.; Hamilton, H.; Meltzer, H.; Goodman, R. Child mental health is everybody’s business: The prevalence of contact with public sector services by type of disorder among British school children in a three-year period. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2007, 12, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner-Seidler, A.; Spanos, S.; Calear, A.L.; Perry, Y.; Torok, M.; O’Dea, B.; Christensen, H.; Newby, J.M. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 89, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Lopez, J.A.; Kwong, A.S.F.; Washbrook, E.; Pearson, R.M.; Tilling, K.; Fazel, M.S.; Kidger, J.; Hammerton, G. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and adult educational and employment outcomes. BJPsych Open 2019, 6, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N.; Wigelsworth, M. Making the case for universal school-based mental health screening. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2016, 21, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y. School mental health: A necessary component of youth mental health policy and plans. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.T.; Abenavoli, R. Universal interventions: Fully exploring their impacts and potential to produce population-level impacts. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2017, 10, 40–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, A.; Demkowicz, O.; Pert, K.; Ashworth, E.; Deighton, J.; Mason, C.; Bray, L. Children and Young People’s Perceptions of Social, Emotional, and Mental Wellbeing Provision and Processes in Primary and Secondary Education: A Qualitative Exploration to Inform NICE Guidance. 2022. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ng10125/documents/supporting-documentation-2 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Murphy, J.M.; Abel, M.R.; Hoover, S.; Jellinek, M.; Fazel, M. Scope, Scale, and Dose of the World’s Largest School-Based Mental Health Programs. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilar, L.; Štiglic, G.; Kmetec, S.; Barr, O.; Pajnkihar, M. Effectiveness of school-based mental well-being interventions among adolescents: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2023–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada-Gallardo, C.; Blasco-Belled, A.; Torrelles-Nadal, C.; Alsinet, C. Effects of School-based Multicomponent Positive Psychology Interventions on Well-being and Distress in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1943–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh-Jones, S.; Beckett, S.; Tumelty, E.; Mallikarjun, P. Indicated prevention interventions for anxiety in children and adolescents: A review and meta-analysis of school-based programs. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, M.L.; Renshaw, T.L.; Caramanico, J.; Greeson, J.M.; MacKenzie, E.; Atkinson-Diaz, Z.; Doppelt, N.; Tai, H.; Mandell, D.S.; Nuske, H.J. Mindfulness-based school interventions: A systematic review of outcome evidence quality by study design. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 1591–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D.; Tudor, K.; Radley, L.; Dalrymple, N.; Funk, J.; Vainre, M.; Ford, T.; Montero-Marin, J.; Kuyken, W.; Dalgleish, T. Do mindfulness-based programmes improve the cognitive skills, behaviour and mental health of children and adolescents? An updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Guz, S.; Zhang, A.; Beretvas, S.N.; Franklin, C.; Kim, J.S. Characteristics of Effective School-Based, Teacher-Delivered Mental Health Services for Children. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2019, 30, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldabbagh, R.; Glazebrook, C.; Sayal, K.; Daley, D. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Teacher Delivered Interventions for Externalizing Behaviors. J. Behav. Educ. 2022, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocks, S.; Stepney, M.; Glogowska, M.; Fazel, M.; Tsiachristas, A. Introducing a Single Point of Access to child and adolescent mental health services in England: A mixed-methods observational study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.; Bates, T.; Birchwood, M. Designing youth mental health services for the 21st century: Examples from Australia, Ireland and the UK. BJ Psychiatry 2013, 202, s30–s35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaglio, M.; O’Donnell, R.; Hatzikiriakidis, K.; Vicary, D.; Skouteris, H. The Impact of Community Mental Health Programs for Australian Youth: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soneson, E.; Howarth, E.; Ford, T.; Humphrey, A.; Jones, P.B.; Thompson Coon, J.; Rogers, M.; Anderson, J.K. Feasibility of school-based identification of children and adolescents experiencing, or at-risk of developing, mental health difficulties: A systematic review. Prev. Sci. 2020, 21, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, B.; Wilson, J.; Clarke, T.; Farthing, S.; Carroll, B.; Jackson, C.; King, K.; Murdoch, J.; Fonagy, P.; Notley, C. Delivering mental health support within schools and colleges—A thematic synthesis of barriers and facilitators to implementation of indicated psychological interventions for adolescents. Child Adolesc. Mental Health 2021, 26, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.R.; Lyon, A.R.; Locke, J.; Waltz, T.; Powell, B.J. Adapting a Compilation of Implementation Strategies to Advance School-Based Implementation Research and Practice. Prev. Sci. 2019, 20, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C.; Clarke, B. Relational matters: A review of the impact of school experience on mental health in early adolescence. Educ. Child Psychol. 2010, 27, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Education Union: State of Education. Mental Health of Young People and Pandemic Recovery. 2022. Available online: https://neu.org.uk/media/21296/view (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Day, L.; Blades, R.; Spence, C.; Ronicle, J. Mental Health Services and Schools Link Pilots: Evaluation. Department for Education. 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/590242/Evaluation_of_the_MH_services_and_schools_link_pilots-RR.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Rothì, D.M.; Leavey, G.; Best, R. On the front-line: Teachers as active observers of pupils’ mental health. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 1217–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Adams, S.; Whiteman, N.; Hughes, J.; Reilly, P.; Dogra, N. Whose responsibility is adolescent’s mental health in the UK? Perspectives of key stakeholders. Sch. Ment. Health 2018, 10, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzer, K.R.; Rickwood, D.J. Teachers’ role breadth and perceived efficacy in supporting student mental health. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2015, 8, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelemy, L.; Harvey, K.; Waite, P. Supporting students’ mental health in schools: What do teachers want and need? Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2019, 24, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Social Care; Department for Education. Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A Green Paper; Department of Health and Department for Education: London, UK, 2017.

- Fazel, M.; Rocks, S.; Glogowska, M.; Stepney, M.; Tsiachristas, A. How does reorganisation in child and adolescent mental health services affect access to services? An observational study of two services in England. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, T.J.; Powell, B.J.; Fernández, M.E.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L.J. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, E.; Long, R.; Bate, A. Children and Young People’s Mental Health: Policy, Services, Funding and Education. Briefing Paper 07196; House of Commons. 2017. Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/30819/1/CBP-7196%20_Redacted.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Ellins, J.; Hockings, L.; Al-Haboubi, M.; Newbould, J.; Fenton, S.-J.; Daniel, K.; Stockwell, S.; Leach, B.; Sidhu, M.; Bousfield, J.; et al. Early Evaluation of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Trailblazer Programme; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/brace/trailblazer.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Lyon, A.A.; Dopp, A.R.; Brewer, S.K.; Kientz, J.A.; Munson, S.A. Designing the future of children’s mental health services. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2020, 47, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorpita, B.F.; Daleiden, E.L.; Weisz, J.R. Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunden S, Rigney G: Lessons learned from sleep education in schools: A review of dos and don’ts. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 671–680. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tindall, L.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; McMillan, D.; Wright, B.; Hewitt, C.; Gascoyne, S. Is behavioural activation effective in the treatment of depression in young people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 90, 770–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.A. A systemic framework for trauma-informed schooling: Complex but necessary! J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2019, 28, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, D.; Hodgson, E.; Bernstein, A.; Chorpita, B.F.; Patel, V. Problem Solving as an Active Ingredient in Indicated Prevention and Treatment of Youth Depression and Anxiety: An Integrative Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, G.; Schlösser, A.; Nash, P.; Glover, L. Targeted group-based interventions in schools to promote emotional well-being: A systematic review. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 412–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neil, A.L.; Christensen, H. Efficacy and effectiveness of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.J.; Chiu, A.W.; Hwang, W.-C.; Jacobs, J.; Ifekwunigwe, M. Adapting cognitive-behavioral therapy for Mexican American students with anxiety disorders: Recommendations for school psychologists. Sch. Psychol. Q 2008, 23, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, M.; Humphrey, N.; Belsky, J.; Deighton, J. Embedding mental health support in schools: Learning from the Targeted Mental Health in Schools (TaMHS) national evaluation. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2013, 18, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.P.; Flynn, D.; Johnson, A.; Maniatopoulos, G.; Newham, J.J.; Perkins, N.; Wood, M.; Woodley, H.; Henderson, E.J. The Implementation of Whole-School Approaches to Transform Mental Health in UK Schools: A Realist Evaluation Protocol. Int. J. Qual Methods 2022, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area of Need in Student/s | 2015–2017 Responses | 2018 Responses | Total for Each Area of Need (% of Logs in Which the Area Was Recorded) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional difficulties | 369 | 363 (anxiety 224; low mood 70; self-harm 69) | 732 (59%) |

| Behavioural problems | 232 | 82 (anger and aggressive behaviour 62; bullying 20) | 314 (25%) |

| Planning with the school | 121 | 154 | 275 (22%) |

| School management | 138 | 91 (broader school management issues 70; safeguarding 21) | 229 (18%) |

| Social difficulties | 159 | 49 (peer problems) | 208 (17%) |

| Parenting issues | 74 | 79 | 153 (12%) |

| Total | 1093 | 818 | 1911 |

| SMHT Tool | Number of Responses (% of Respondents) |

|---|---|

| Relaxation techniques | 44 (42) |

| Sleep hygiene advice | 44 (42) |

| Active listening | 37 (35) |

| Treasure box to prepare for difficult situations | 33 (31) |

| Ice-breakers | 20 (19) |

| Problem solving | 20 (19) |

| Behavioural change | 16 (15) |

| Pleasurable experiences | 15 (14) |

| Map of social networks | 13 (12) |

| How to help a student who has experienced trauma | 12 (11) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fazel, M.; Soneson, E.; Sellars, E.; Butler, G.; Stein, A. Partnerships at the Interface of Education and Mental Health Services: The Utilisation and Acceptability of the Provision of Specialist Liaison and Teacher Skills Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054066

Fazel M, Soneson E, Sellars E, Butler G, Stein A. Partnerships at the Interface of Education and Mental Health Services: The Utilisation and Acceptability of the Provision of Specialist Liaison and Teacher Skills Training. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054066

Chicago/Turabian StyleFazel, Mina, Emma Soneson, Elise Sellars, Gillian Butler, and Alan Stein. 2023. "Partnerships at the Interface of Education and Mental Health Services: The Utilisation and Acceptability of the Provision of Specialist Liaison and Teacher Skills Training" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054066

APA StyleFazel, M., Soneson, E., Sellars, E., Butler, G., & Stein, A. (2023). Partnerships at the Interface of Education and Mental Health Services: The Utilisation and Acceptability of the Provision of Specialist Liaison and Teacher Skills Training. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054066