Investigating the Role of Friendship Interventions on the Mental Health Outcomes of Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Range and a Systematic Review of Effectiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

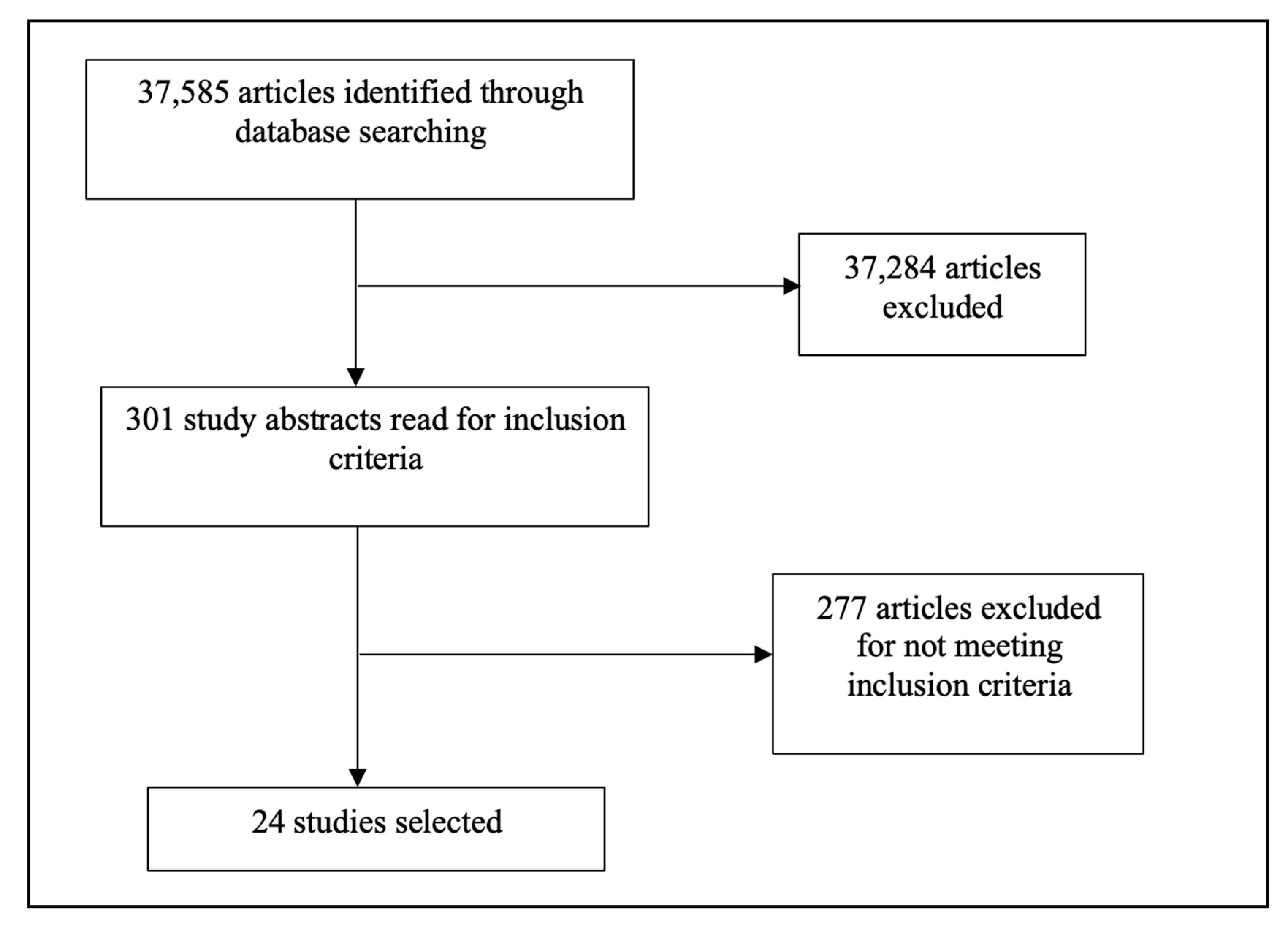

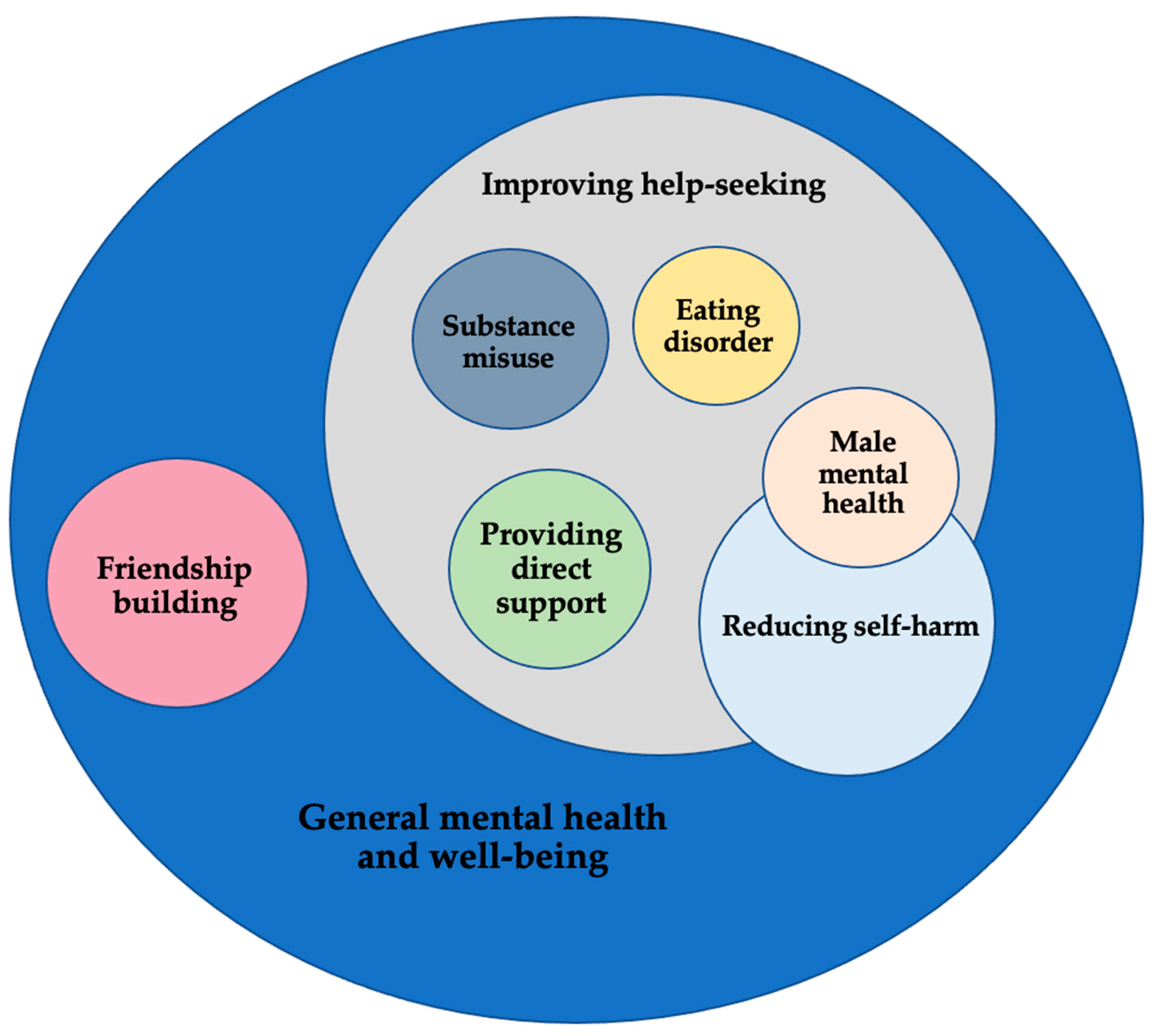

3. Scoping Review

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Scoping Review Results

3.2.1. General Mental Health and Well-Being

3.2.2. Improving Help-Seeking

3.2.3. Friendship-Building/Combating Isolation

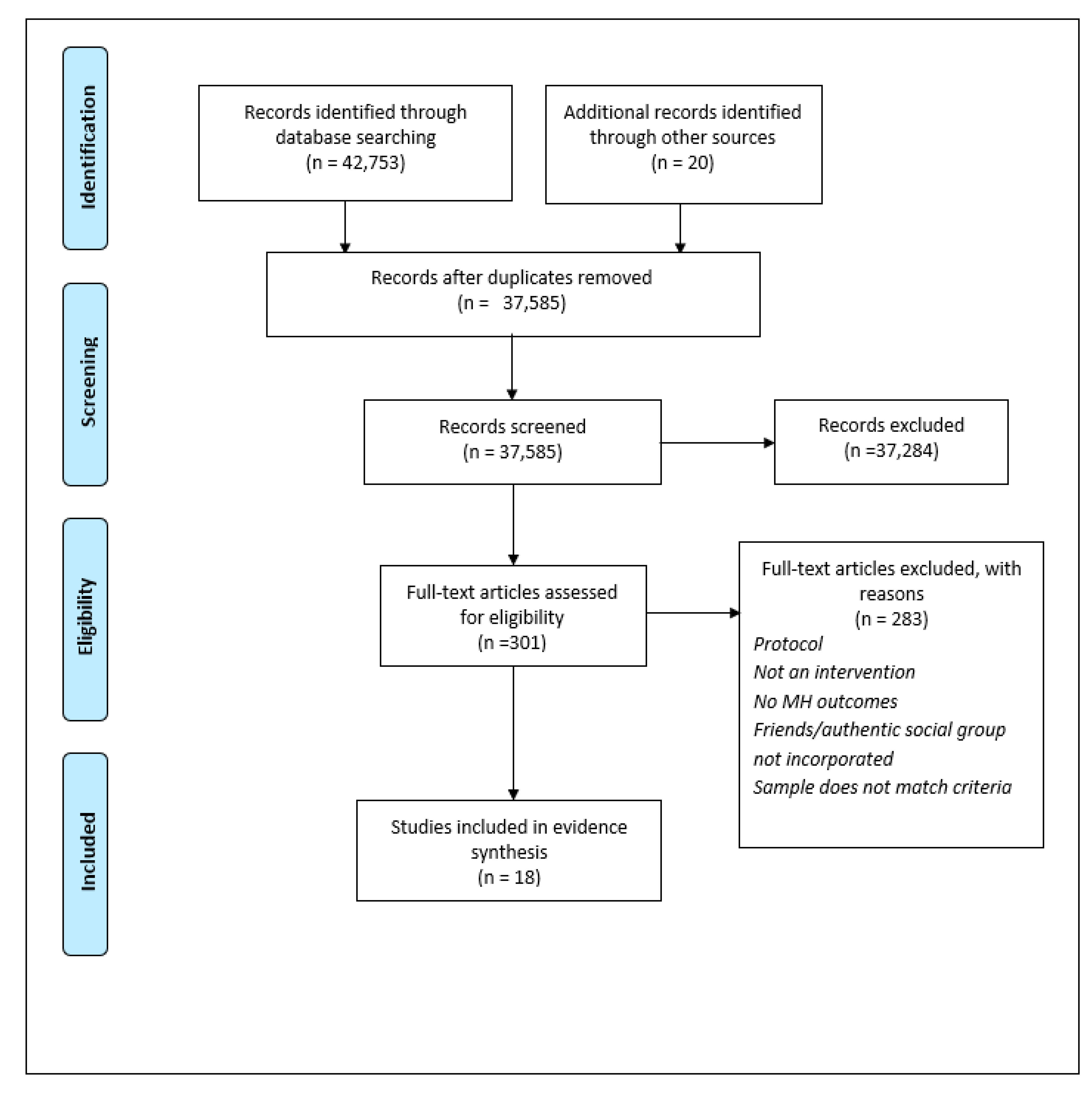

4. Systematic Review

4.1. Methodology

4.2. Inclusion Criteria

4.3. Quality of Included Studies

4.4. Systematic Review Results

4.4.1. Description of Studies

4.4.2. Intervention Outcomes

4.4.3. Inferred Outcomes of Intervention on FR

4.4.4. Outcomes of Intervention on FT

4.5. Mental Health Literacy

4.5.1. Improving Help-Seeking

4.5.2. Friendship Building

5. Discussion

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J.; Burnett, S.; Dahl, R.E. The role of puberty in the developing adolescent brain. Human Brain Mapp. 2010, 31, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedd, J.N.; Blumenthal, J.; Jeffries, N.O.; Castellanos, F.; Liu, H.; Zijdenbos, A.; Paus, T.; Evans, A.C.; Rapoport, J.L. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nat. Neurosci. 1999, 2, 861–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, E.A.; Dahl, R.E. Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.; Ciarrochi, J. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust. e-J. Adv. Ment. Health 2005, 4 (Suppl. S2), 218–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Newcomb, A.F.; Hartup, W.W. The Company They Keep: Friendships in Childhood and Adolescence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup, W.W.; Stevens, N. Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, A.M.; Prinstein, M.J. Peer group. In Developmental Issues in the Clinical Treatment of Children; Allyn Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 171–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup, W.W. The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, W.; Buhrmester, D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, R.; Richards, M.H. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: Changing developmental contexts. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayborne, Z.M.; Varin, M.; Colman, I. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Adolescent Depression and Long-Term Psychosocial Outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geulayov, G.; Borschmann, R.; Mansfield, K.L.; Hawton, K.; Moran, P.; Fazel, M. Utilization and Acceptability of Formal and Informal Support for Adolescents Following Self-Harm before and during the First COVID-19 Lockdown: Results from a Large-Scale English Schools Survey. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 881248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camara, M.; Bacigalupe, G.; Padilla, P. The role of social support in adolescents: Are you helping me or stressing me out? Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2007, 22, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Hoza, B.; Boivin, M. Measuring Friendship Quality During Pre- and Early Adolescence: The Development and Psychometric Properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1994, 11, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Thomson, K.C. Understanding the Link between Social and Emotional Well-Being and Peer Relations in Early Adolescence: Gender-Specific Predictors of Peer Acceptance. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 1330–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güroğlu, B. Adolescent brain in a social world: Unravelling the positive power of peers from a neurobehavioral perspective. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 18, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Laursen, B.; Hoza, B. The snowball effect: Friendship moderates escalations in depressed affect among avoidant and excluded children. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, C.L.; Eisenberger, N.I.; Pfeifer, J.H.; Dapretto, M. Witnessing peer rejection during early adolescence: Neural correlates of empathy for experiences of social exclusion. Soc. Neurosci. 2010, 5, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, M.; Baumgartner, T.; Kirschbaum, C.; Ehlert, U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colarossi, L.; Eccles, J. Differential effects of support providers on adolescent mental health. Soc. Work. Res. 2003, 27, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uink, B.; Modecki, K.; Barber, B. Disadvantaged youth report less negative emotion to minor stressors when with peers: An experience sampling study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 43, NP1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.; Bellamy, C.; Guy, K.; Miller, R. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: A review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalan, G.; Lee, S.J.; Harris, R.; Acri, M.C.; Munson, M.R. Utilization of peers in services for youth with emotional and behavioral challenges: A scoping review. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, E.L. Self-Help and Serious Mental Illness. Medscape Gen. Med. 2006, 8, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, L.; Chinman, M.; Kloos, B.; Weingarten, R.; Stayner, D.; Tebes, J.K. Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1999, 6, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Fazel, M. Examining the mental health outcomes of school-based peer-led interventions on young people: A scoping review of range and a systematic review of effectiveness. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, T.; Stein, A.; Fazel, M. A Scoping Review Investigating the Role of Friendship Interventions on the Mental Health Outcomes of Adolescents. The OxWell School Survey on Mental Health and Wellbeing. Available online: https://osf.io/mnvt4 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Morgan, A.J.; Fischer, J.A.; Hart, L.M.; Kelly, C.M.; Kitchener, B.A.; Reavley, N.J.; Yap, M.; Jorm, A.F. Long-term effects of Youth Mental Health First Aid training: Randomized controlled trial with 3-year follow-up. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig Rushing, S.; Kelley, A.; Bull, S.; Stephens, D.; Wrobel, J.; Silvasstar, J.; Peterson, R.; Begay, C.; Ghost Dog, T.; McCray, C.; et al. Efficacy of an mHealth Intervention (BRAVE) to Promote Mental Wellness for American Indian and Alaska Native Teenagers and Young Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e26158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, E.B.; Beever, E.; Glazebrook, C. A pilot randomised controlled study of the mental health first aid eLearning course with UK medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavarini, G.; Reardon, T.; Hollowell, A.; Bennett, V.; Lawrance, E.; Pinfold, V.; Singh, I. Online peer support training to promote adolescents’ emotional support skills, mental health and agency during COVID-19: Randomised controlled trial and qualitative evaluation. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BeyondBlue. The Check-In App—Apple Store. Available online: https://www.beyondblue.org.au/about-us/about-our-work/young-people/the-check-in-app (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- ConNetica. Chats for Life—Apple Store. ReachOut. Available online: https://au.reachout.com/tools-and-apps/chats-for-life (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Ashoorian, D.; Albrecht, K.L.; Baxter, C.; Giftakis, E.; Clifford, R.; Greenwell-Barnden, J.; Wylde, T. Evaluation of Mental Health First Aid skills in an Australian university population. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Ojio, Y.; Foo, J.C.; Michigami, E.; Usami, S.; Fuyama, T.; Onuma, K.; Oshima, N.; Ando, S.; Togo, F.; et al. A quasi-cluster randomised controlled trial of a classroom-based mental health literacy educational intervention to promote knowledge and help-seeking/helping behaviour in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2020, 82, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrell, L.; Furneaux-Bate, A.; Debenham, J.; Spallek, S.; Newton, N.; Chapman, C. Development of a Peer Support Mobile App and Web-Based Lesson for Adolescent Mental Health (Mind Your Mate): User-Centered Design Approach. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, S.K.; Deane, F.P.; Batterham, M.; Vella, S.A. A Brief Sports-Based Mental Health Literacy Program for Male Adolescents: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2021, 33, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A.L.; Morse, A.R.; Batterham, P.J.; Forbes, O.; Banfield, M. Silence is Deadly: A controlled trial of a public health intervention to promote help-seeking in adolescent males. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2021, 51, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, B.J.; Hall, K.; Dillon, P.; Hides, L.; Lubman, D.I. Makingthelink: A school-based health promotion programme to increase help-seeking for cannabis and mental health issues among adolescents. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2011, 5, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubman, D.I.; Cheetham, A.; Jorm, A.F.; Berridge, B.J.; Wilson, C.; Blee, F.; Mckay-Brown, L.; Allen, N.; Proimos, J. Australian adolescents’ beliefs and help-seeking intentions towards peers experiencing symptoms of depression and alcohol misuse. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseltine RH and DeMartino R An outcome evaluation of the SOS suicide prevention program. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 446–451. [CrossRef]

- McGillivray, L.; Shand, F.; Calear, A.; Batterham, P.; Rheinberger, D.; Chen, N.; Burnett, A.; Torok, M. The Youth Aware of Mental Health program in Australian Secondary Schools: 3- and 6-month outcomes. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, L.M.; Morgan, A.J.; Rossetto, A.; Kelly, C.M.; Gregg, K.; Gross, M.; Johnson, C.; Jorm, A.F. teen Mental Health First Aid: 12-month outcomes from a cluster crossover randomized controlled trial evaluation of a universal program to help adolescents better support peers with a mental health problem. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; Black, N.; Ng, J.; Blumenthal, E. Kognito’s Avatar-Based Suicide Prevention Training for College Students: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial and a Naturalistic Evaluation. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyman, P.A.; Brown, C.H.; LoMurray, M.; Schmeelk-Cone, K.; Petrova, M.; Yu, Q.; Walsh, E.; Tu, X.; Wang, W. An outcome evaluation of the Sources of Strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damour, L.K.; Cordiano, T.S.; Anderson-Fye, E.P. My sister’s keeper: Identifying eating pathology through peer networks. Eat. Disord. 2015, 23, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernecker, S.L.; Williams, J.J.; Caporale-Berkowitz, N.A.; Wasil, A.R.; Constantino, M.J. Nonprofessional Peer Support to Improve Mental Health: Randomized Trial of a Scalable Web-Based Peer Counseling Course. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, P.; Pendley, J.S.; McDonell, K.; Reeves, G. A Peer Group Intervention for Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes and Their Best Friends. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2001, 26, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boda, Z.; Elmer, T.; Vörös, A.; Stadtfeld, C. Short-term and long-term effects of a social network intervention on friendships among university students. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devassy, S.M.; Allagh, K.P.; Benny, A.M.; Scaria, L.; Cheguvera, N.; Sunirose, I.P. Resiliency Engagement and Care in Health (REaCH): A telephone befriending intervention for upskilled rural youth in the context of COVID-19 pandemic-study protocol for a multi-centre cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.; Hawes, D.J.; Hunt, C.J. Randomized controlled trial of a friendship skills intervention on adolescent depressive symptoms. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; Cruwys, T.; Haslam, S.A.; Dingle, G.; Chang, M.X.-L. Groups 4 Health: Evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 194, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing Review Questions and Planning the Systematic Review; NICE: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS ONE 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, A.; Bellissimo, A.; Norman, G.; Lange, P. Adolescent depression in a school-based community sample: Preliminary findings on contributing social factors. J. Youth Adolesc. 1994, 23, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Harmelen, A.L.; Gibson, J.L.; St Clair, M.C.; Owens, M.; Brodbeck, J.; Dunn, V.; Lewis, G.; Croudace, T.; Jones, P.B.; Kievit, R.A.; et al. Friendships and Family Support Reduce Subsequent Depressive Symptoms in At-Risk Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N. Generation Z’s smartphone and social media usage: A survey. J. Mass Commun. 2019, 9, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittmann, G.; Woodcock, K.; Dörfler, S.; Krammer, I.; Pollak, I.; Schrank, B. “TikTok Is My Life and Snapchat Is My Ventricle”: A Mixed-Methods Study on the Role of Online Communication Tools for Friendships in Early Adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2022, 42, 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniel-Nissim, M.; van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Furstova, J.; Marino, C.; Lahti, H.; Inchley, J.; Smigelskas, K.; Vieno, A.; Badura, P. International perspectives on social media use among adolescents: Implications for mental and social well-being and substance use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, J.; Thieleman, K.; Fretts, R.; Jackson, L.B. What is good grief support? Exploring the actors and actions in social support after traumatic grief. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergersen, E.B.; Larsson, M.; Olsson, C. Children and adolescents’ preferences for support when living with a dying parent—An integrative review. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 1536–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, L.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Mcmillan, D.; Wright, B.; Hewitt, C.; Gascoyne, S. Is behavioural activation effective in the treatment of depression in young people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2017, 90, 770–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, F.; Westbrook, J.; Gee, B.; Clarke, T.; Allan, S.; Pass, L. Self-evaluation as an active ingredient in the experience and treatment of adolescent depression; an integrated scoping review with expert advisory input. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M. A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Friendship Research. ISSBD Newsl. 2004, 46, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Harrop, C.; Ellett, L.; Brand, R.; Lobban, F. Friends interventions in psychosis: A narrative review and call to action. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2015, 9, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Year | Location | Average Age | In-Person (IPR) or Remote (RMT) | Intervention Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder | ||||

| Damour et al. (2015) | United States of America | 13.9–14.9 | IPR | Eighth and ninth-grade class lessons to females on identifying a potential eating disorder in themselves or their friends. The intervention aimed to teach them to approach an adult if they suspect a friend has an eating disorder and how to support them. |

| Friendship-building/Social Connectedness | ||||

| Boda et al. (2020) | Switzerland | First year undergraduates | IPR | First-year undergraduate engineering students were randomly assigned to groups for a few hours on a student information day to facilitate friendships, especially mixed-gender friendships, to combat feelings of isolation and increase well-being and support. |

| Devassy et al. (2021) | India | 18–35 | RMT | A telephone-based intervention to encourage participants to seek support from their social circle (friends, family, significant others) to combat depressive symptoms, anxiety, etc. |

| Haslam et al. (2016) | Australia | 20.2 | IPR | Pilot study of an intervention for university students to improve students’ well-being, mental health, and social connectedness by helping participants build a social support network of friends and social group identity through a group-based intervention. |

| Rose et al. (2014) | Australia | 12.22 | IPR | Whole classrooms of adolescents were taught skills to make friendships in the first intervention, followed by a second intervention in conjunction to reduce depressive symptoms and increase general well-being, while promoting support skills for friends. |

| General mental health and well-being | ||||

| Ashoorian et al. (2018) | Australia | 24 | IPR | Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) intervention for university student groups that are well-placed to provide early intervention to their peers (ex. student representatives, student leaders, etc.) by teaching them skills to recognize signs of mental distress/illness. Students were trained to apply MHFA skills to their friends. |

| Birrell et al. (2022) | Australia | 15.9 | IPR and RMT | A smartphone peer support app and introductory classroom lesson aimed at empowering adolescents to access evidence-based information and tools to better support peers regarding anxiety, depression, and substance use-related issues. The programme contains external links for adolescents to access if they are concerned about a friend or themselves. |

| The Check-In App. BeyondBlue (mHealth App) | Australia | Young people | RMT | A smartphone app co-produced by young people to facilitate talking to a friend who might be struggling with mental illness. The app provides the user with advice for how to help their friend, while also looking after their own mental health. The interface also provides online and phone resources. |

| ConNetica. Chats for life (mHealth App) | Australia | Young people | RMT | A smartphone app co-designed with young people to help them plan a conversation with a friend who may be struggling with a mental health issue. The app provides video guides for users for how they can support their friends’ mental health and well-being. |

| Craig Rushing et al. (2021) | United States of America | 15–24 | RMT | BRAVE is a text message-based intervention for Native youth to promote mental well-being and help-seeking skills. Text messages and role-model videos are sent to Native youth participating in the study in an effort to increase social support, help-seeking, mental health literacy, and well-being. |

| Davies et al. (2018) | United Kingdom | 19.9 | RMT | Mental health literacy and first aid training using MHFA intervention for medical students to teach them how to recognize signs of mental illness, and increase confidence in providing mental health support to friends. |

| Pavarini et al. (2022) | United Kingdom | 16–18 | RMT | A training programme with the aim of teaching adolescents how to best support their friends’ mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. The programme was delivered to adolescents by a trained team of Youth Era peer support experts over five consecutive days. |

| Yamaguchi et al. (2020) | Japan | 15–16 | IPR | Short Mental Health Program (SMHLP) is a 50 min teacher-led intervention to teach adolescents about mental health symptoms, improve help-seeking behaviours and increase intentions to support a friend displaying signs of mental distress. |

| Male mental health | ||||

| Calear et al. (2021) | Australia | 16–18 | IPR | An intervention to promote help-seeking for emotional distress and self-harm amongst adolescent males. The intervention aimed to encourage adolescent males to seek help from and provide support to friends in times of distress or suicide risk. |

| Liddle et al. (2021) | Australia | 14.3 | IPR | A 45 min workshop, Help Out a Mate (HOAM), designed to educate male adolescents on mental health, support skills, and how to access appropriate resources for themselves or a friend. The intervention was delivered in a sports setting and included a PowerPoint presentation, facilitated discussions between participants and presenters, and brief role-plays. |

| Psychotherapy/Peer Counselling | ||||

| Bernecker et al. (2020) | United States of America | 24.6 | RMT | An intervention called “Crowdsourcing mental health (CMH)”, a self-guided web-based course, teaches reciprocal supportive psychotherapy skills to pairs of friends. Dyads alternate between helper and receiver role. |

| Reduction of self-harm | ||||

| Aseltine and DeMartino (2004) | United States of America | Grades 9–12 | IPR | Signs of Suicide (SOS) school-based prevention programme to teach adolescents how to recognize the signs of depression and/or self-harm and empower them to support and intervene when a friend may be exhibiting these signs. |

| Coleman et al. (2019) | United States of America | 20.5 | RMT | An online suicide-prevention gatekeeper training intervention called “Kognito Face2Face” was given to enhance adolescents’ help-seeking attitudes and peer-help attitudes. The trainee adolescent is put in a simulated college social environment in Kognito and interacts with virtual peers. The trainee has to identify peers who may be at risk by engaging in dialogue, deciding if a professional referral is needed, and referring their peer to a professional for help. |

| Hart et al. (2022) | Australia | 15.87 | IPR | Teen Mental Health First Aid (tMHFA) is a mental health literacy programme implemented in secondary schools in a classroom setting by trained professionals to teach adolescents how to respond to a friend at risk of self-harm. Students are trained to recognize signs of mental distress and suicidality in their peers. Training involves vignettes of virtual peers in distress. Changes in providing support are measured through a survey administered before training and a survey administered 12 months after training. |

| McGillivray et al. (2021) | Australia | 14.4 | IPR | Implementation of a universal mental health programme, Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) to reduce suicidal ideation and depression, and increase help-seeking. YAM includes discussions and role-plays based on the following topics: What is mental health, self-help advice, stress and crisis, depression and suicidal thoughts, helping a friend in need, and getting advice: who to contact. |

| Wyman et al. (2010) | United States of America | 15–16 | IPR and RMT | Schoolwide suicide prevention intervention (Sources of Strength) delivered through trained peer leaders to encourage their friends to seek help for themselves and their friends at risk of suicide. |

| Substance misuse | ||||

| Berridge et al. (2011) | Australia | 15 | IPR | A school-based health promotion programme (MakingTheLink) that promotes help-seeking behaviour for mental health issues and cannabis use among young people. Scenarios are used to train students in how to respond if a friend shows similar signs. |

| Lubman et al. (2017) | Australia | 14.9 | IPR | A school-based health promotion programme (MakingTheLink) where secondary school students were presented with two vignettes of peers, Sarah and Samuel, depicting depression and alcohol misuse to improve help-seeking intentions and encourage adolescents to support their friends. |

| Well-being related to other illnesses | ||||

| Greco et al. (2001) | United States of America | 13.1–13.6 | IPR | Diabetic adolescents and one of their friends participated in an intervention to improve knowledge about diabetes, social support, and social functioning. The intervention aimed to increase positive peer involvement and emotional support for friends with diabetes. |

| Author, Year, and Location | Research Design | N | Approximate Average Participant Age | Intervention Type | Frequency/Duration of Programme | Participant and Peer Selection Process | Training | Intervention Outcomes and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aseltine and DeMartino (2004), USA [47] | RCT | 2100 | 14–18 * | Mental illness prevention intervention | 2 days | Whole classes recruited from secondary schools. | Signs of Suicide (SOS) is a school-based prevention programme delivered in a classroom to help students identify markers of suicide in themselves and their friends. Schools receive a kit of materials containing the DVD of informational videos, discussion guide, screening forms, and other educational and promotional items. They also receive the procedure manual that describes how to implement the programme. | Short-term effects on students’ behaviours were observed with more adaptive attitudes towards depression and suicide. Students were more likely to provide support to friends showing signs of distress. Discussions conducted in classes several months after exposure to the programme revealed that students were unlikely to seek out school staff for MH concerns, primarily because of confidentiality. Instead, students reported that friends were the first people they would turn to when feeling depressed. |

| Bernecker et al. (2020), USA [53] | RCT | 60 | 24.6 | MH literacy and support skills intervention | Course taken over four weeks. | Recruited participants asked to recruit a friend from their existing social circle. | Participants were brought into the laboratory to first talk about their stressors before the course. Then, participants completed an online training course and had to use skills learned to go through helper and talker role in vignettes. | Participants in the intervention group changed some behaviours to better support peers (e.g., talking less about themselves and listening more when a friend shares a problem). No change in feelings of supportiveness or closeness with their friends was reported. |

| Berridge et al. (2011), Australia [45] | Pre-post | 182 | 15 | MH literacy and help-seeking intervention | Two class lessons. | Students recruited from Year 10 (aged 15) classes. | A school-based intervention where facilitators with backgrounds in teaching and mental health deliver the programme in classrooms. | Students and teachers reported feeling better informed about mental health and substance abuse disorders. Students who completed the programme reported increased confidence to seek help for themselves or a friend. |

| Boda et al. (2020), Switzerland [55] | RCT | 226 | 18–19 * | Friendship building and MH support | Range | An incoming cohort of engineering students recruited | Students were randomly assigned to groups during their orientation week and completed activities to facilitate friendship. | Students in the intervention group developed more friendships and had more individuals they could turn to for emotional support. A 12-month follow up revealed that friendships did not last. |

| Calear et al. (2021), Australia [44] | Two-arm controlled trial | 594 (males only) | 16–18 | MH help-seeking (male targeted) | 45–60 min presentation | Government colleges and private secondary schools invited to participate. | Menslink ‘Silence is Deadly’ programme is a psychoeducational intervention including key statistics about mental health presented alongside personal experiences of the presenters. It includes a presentation, supporting website, videos, and wristband. | Intervention significantly increased help-seeking intentions of participants from friends for emotional problems and mental distress. No difference was found for confidence to support their friends or reduce MH stigma. |

| Coleman et al. (2019), USA [50] | RCT | 69 | 20.5 | Suicide prevention and gate-keeper training | Range | Recruited from two large undergraduate lecture courses. | Participants were given avatar-based online training where they were trained in identifying and clarifying risk and then in encouraging an at-risk friend to seek help. | The intervention was successful in increasing participants’ intention to provide support to a friend with mental illness and increased chances of referring a friend to professional services (i.e., counselling centre). |

| Craig Rushing et al. (2021), USA [35] | RCT | 833 | 15–24 | MH literacy and help-seeking | 8 weeks | Social media and SMS recruitment of Native American and Alaska Native teenagers from the community. | SMS text messages about wellness, MH, help-seeking, etc., were sent out to participants three times per week for eight weeks. | Participants reported using the informative SMS text messages to help family and friends. Follow up after 3 months revealed 22.4% of participants reported using skills learned from SMS messages to offer help and by 8 months there was an increase to 54.6% of participants. |

| Davies et al. (2018), UK [36] | RCT | 55 | 19.9 | MH literacy and support skills | 6 weeks | Medical students recruited. | MHFA E-learning course | Intentions and confidence to help a friend with mental illness increased and stigma towards mental illness decreased. An increase in MH first aid skills was also found. |

| Greco et al. (2001), USA [54] | Pre-post | 42 | 13.1–13.6 | Integrating friends into care | 4 weeks | Diabetic adolescents asked to bring a ‘best friend’. | Four 2 h education and support group sessions led by licensed psychologists. | Friend support increased following the intervention. Trained ‘friends’ were more educated on their friend’s condition and learned how to help support the well-being of a diabetic friend. |

| Hart et al. (2022), Australia [49] | Cluster randomised crossover trial | 1605 | 15.87 | MH literacy and peer support training for suicide prevention | Training for the tMHFA, three 75 min classroom sessions | Students recruited from high schools. | MH literacy intervention provided to adolescents, with activities and vignettes led by an external instructor. | Students receiving tMHFA training more likely to report improved recognition of suicidality and appropriately respond to and provide first aid intentions towards a peer at risk of self-harm than students in active control arm. |

| Haslam et al. (2016), Australia [58] | Non-randomized control trial | 51 | 20.2–20.95 | Friendship building and isolation | Modules of 60–75 min once a week over four weeks. Last module delivered a month after the 4th. | University undergraduates and students from a concurrent study (control). All participants screened, and only those with some kind of psychological distress or social isolation included. | Five-module psychological intervention targeting the development and maintenance of social group relationships to improve psychological distress arising from social isolation. | Groups 4 Health (G4H) intervention was successful in increasing mental health outcomes, well-being, and social connectedness, both on programme completion and 6-month follow up. Participants also had improved social connectedness with peers and increased group-identification. |

| Liddle et al. (2021), Australia [43] | Cluster randomised controlled trial | 102 (males only) | 14.3 | MH literacy and help-seeking intervention | 45 min session. | Recruited from a male community football club. | Presentation, facilitated discussions and brief role-plays delivered in a sports context. Adolescents were provided with a card listing support and resource options. Volunteer student facilitators with lived experience of mental illness led the workshop. | Compared to the control group, the adolescents receiving the intervention showed improvements in mental health literacy for anxiety and depression, along with intentions to provide help to a friend. Further, improvements in attitudes that promote help-seeking and reduce stigma were also observed. |

| Lubman et al. (2017), Australia [46] | RCT | 2456 | 14.9 | MH literacy and help-seeking intervention | Range | Participants recruited from secondary schools. | MakingTheLink is a school-based intervention where participants are presented with vignettes (depression and alcohol misuse) and asked to respond to scenarios to provide help. | Pre-post survey results revealed that, after the intervention, adolescents were more likely to seek help for friends showing signs of depression or alcohol misuse. They were also more likely to seek help for themselves. |

| McGillivray et al. (2021), Australia [48] | Pre-post | 556 | 14.4 | MH literacy and suicide prevention | Five classroom lessons over three weeks. | Secondary schools invited to participate. | The Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) programme is a school-based programme delivered by trained facilitators and includes booklets, discussions, and role-play activities which allow adolescents to discuss mental health and improve problem-solving and emotional functioning in difficult real-life situations. | There was a reduction in depression severity and suicidal ideation, and an increase in help-seeking intentions at 3 months post-intervention and 6 months follow-up. |

| Pavarini et al. (2022), UK [37] | RCT | 100 | 16–18 | MH literacy and support skills intervention | 5 days | Poster/advert community recruitment. | Uplift peer support training course delivered online (Zoom). Interactive sessions including sharing and hands-on activities were delivered through breakout rooms or WhatsApp. | All participants reported an increase in MH knowledge and reported using the learned skills to support at least one friend/peer in their social circle with mental health difficulties. |

| Rose et al. (2014), Australia [57] | RCT | 210 | 12.22 | Friendship building | 9–11 weekly sessions lasting 40–50 min each. | Cluster randomization of 14 classes across four schools. | Combination of two interventions (RAP and PIR) implemented together in a school during class time by trained facilitators, where one targets social network building and the other targets depression prevention. | Students reported significantly higher levels of peer interpersonal relatedness when reassessed 12 months after the intervention. Significant increases in social functioning with peers was also noted. |

| Wyman et al. (2010), USA [51] | RCT | 2675 | 15–16 | Suicide prevention and gate-keeper training | Three phases: (1) school and community preparation, (2) peer leader training, and (3) schoolwide messaging. Phases 1 and 3 ranged in time and phase 2 was 4 h long. | Students recruited from high school. Peer leaders chosen to reflect a diverse range of friendship groups. | Certified trainers focused training on coping skills and available resources such as friends. Trained students (peer leaders) encouraged their friends to reach out to trusted adults and disseminated messages about the intervention through PSAs and social media. | Trained peer leaders were more likely to refer a suicidal friend to an adult and the intervention increased perceptions of adult support in students with a history of suicidal ideation. The intervention was also found to increase the acceptability of seeking help and the confidence to seek and provide support. |

| Yamaguchi et al. (2020), Japan [41] | Quasi-experimental | 899 | 15–16 | MH literacy and support skills intervention | 50 min | Participants recruited from a high school. | Teacher-delivered intervention through films, discussions, and role-play. | The intervention showed short-term and long-term (2 months) effects. Students’ intention to seek help and intention to help a peer with signs of mental illness increased. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manchanda, T.; Stein, A.; Fazel, M. Investigating the Role of Friendship Interventions on the Mental Health Outcomes of Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Range and a Systematic Review of Effectiveness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032160

Manchanda T, Stein A, Fazel M. Investigating the Role of Friendship Interventions on the Mental Health Outcomes of Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Range and a Systematic Review of Effectiveness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032160

Chicago/Turabian StyleManchanda, Tanya, Alan Stein, and Mina Fazel. 2023. "Investigating the Role of Friendship Interventions on the Mental Health Outcomes of Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Range and a Systematic Review of Effectiveness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032160

APA StyleManchanda, T., Stein, A., & Fazel, M. (2023). Investigating the Role of Friendship Interventions on the Mental Health Outcomes of Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Range and a Systematic Review of Effectiveness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032160