The Impact of Digital Coaching Intervention for Improving Healthy Ageing Dimensions among Older Adults during Their Transition from Work to Retirement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

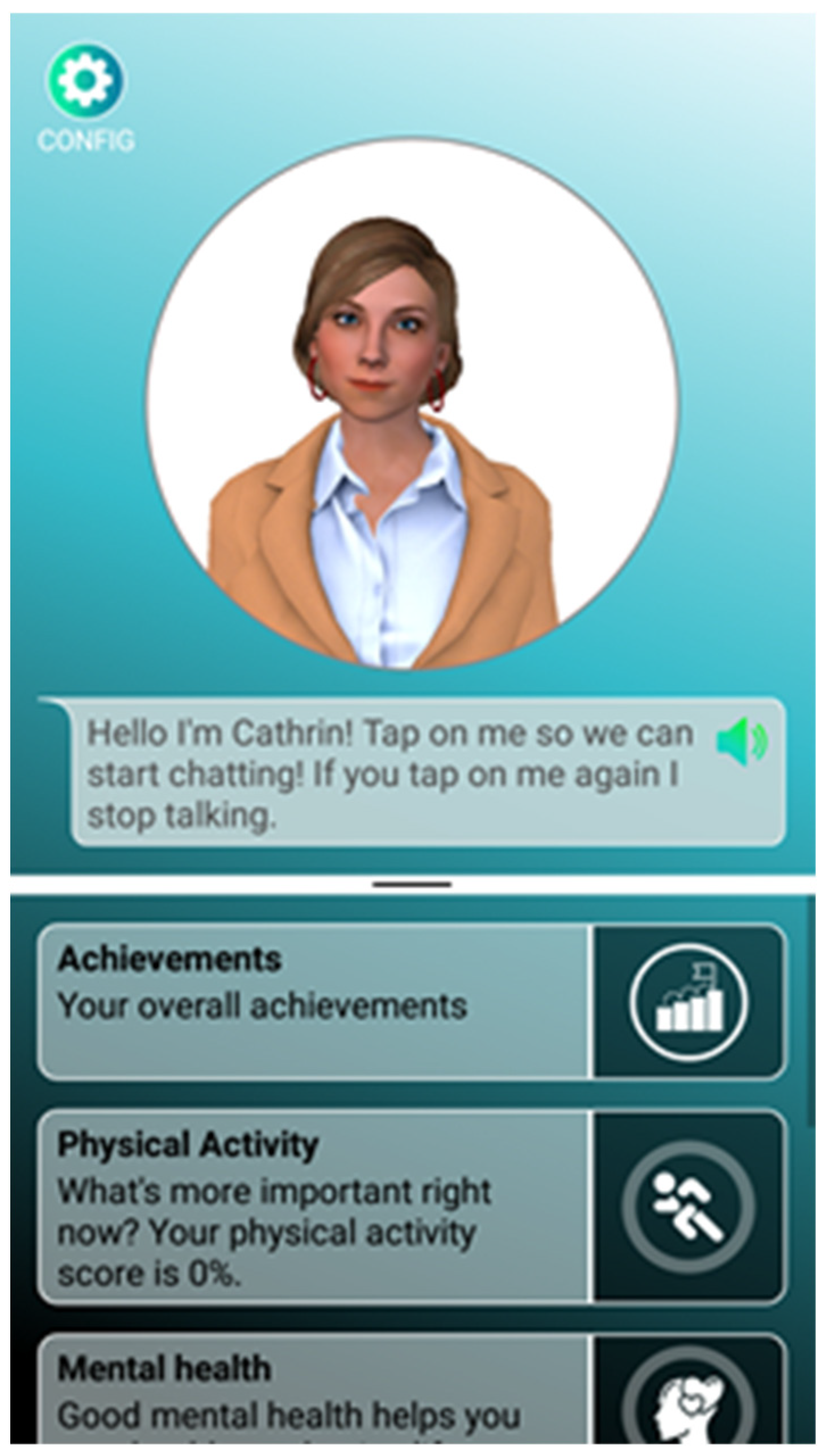

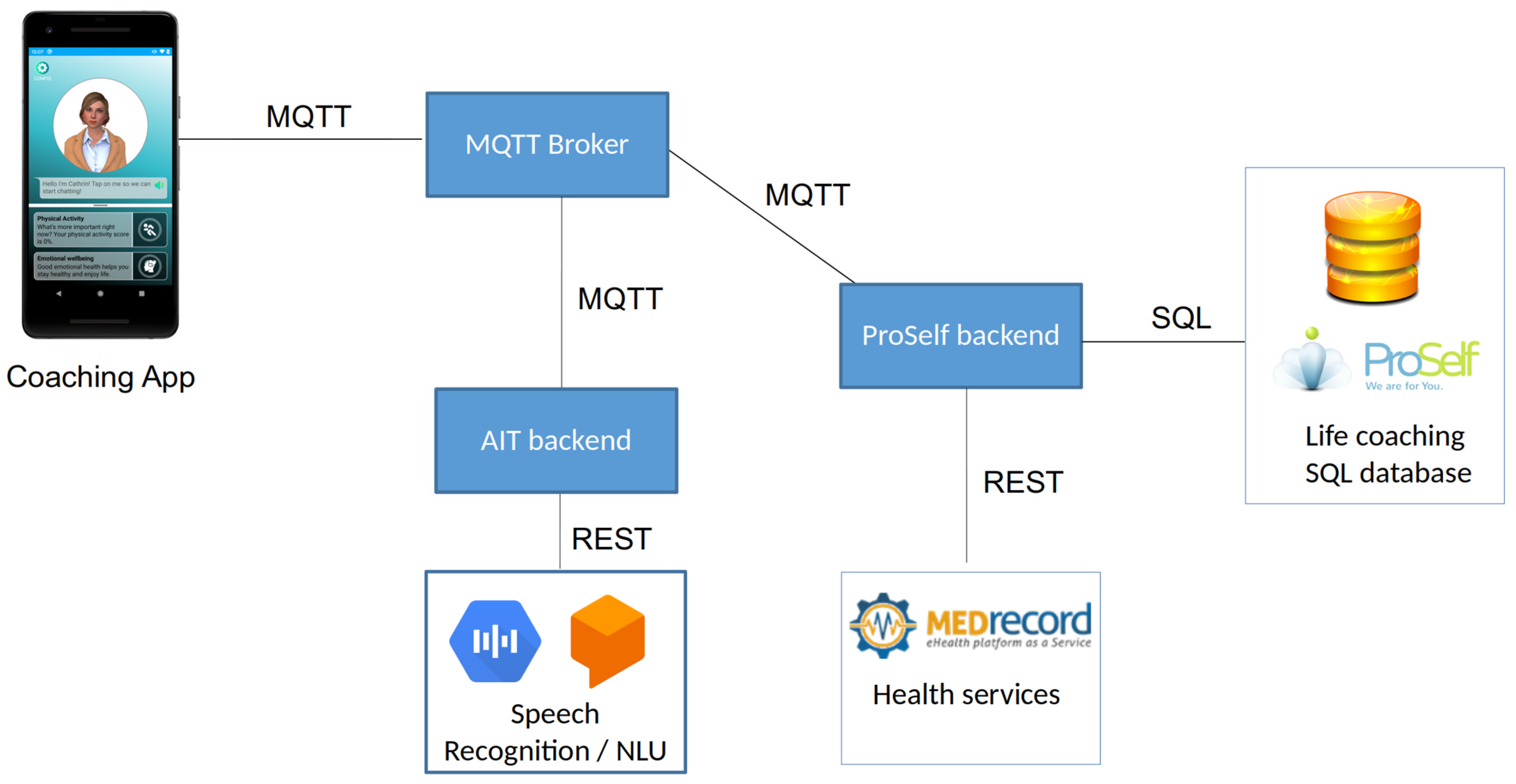

2.1. The System

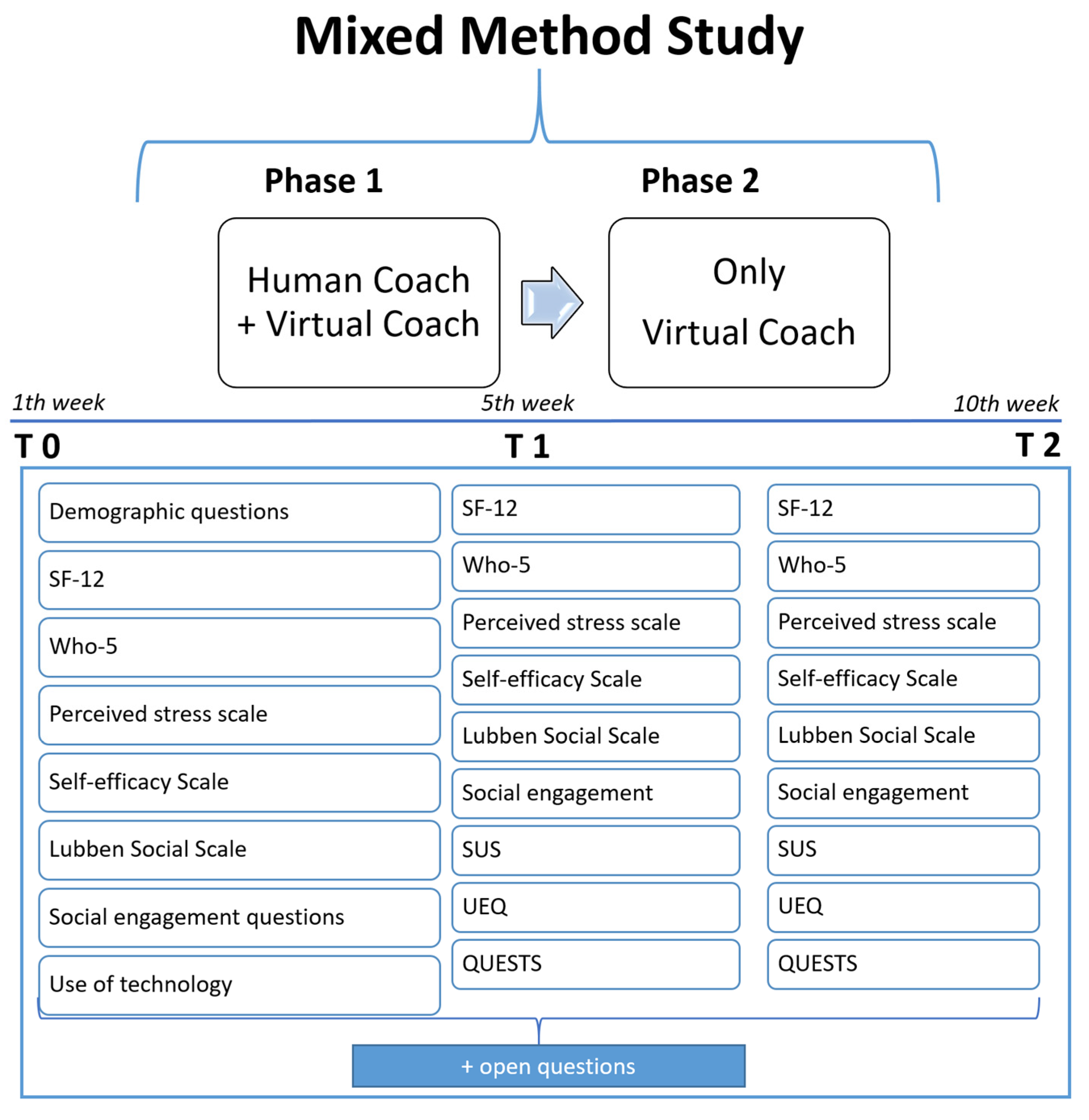

2.2. Study Design

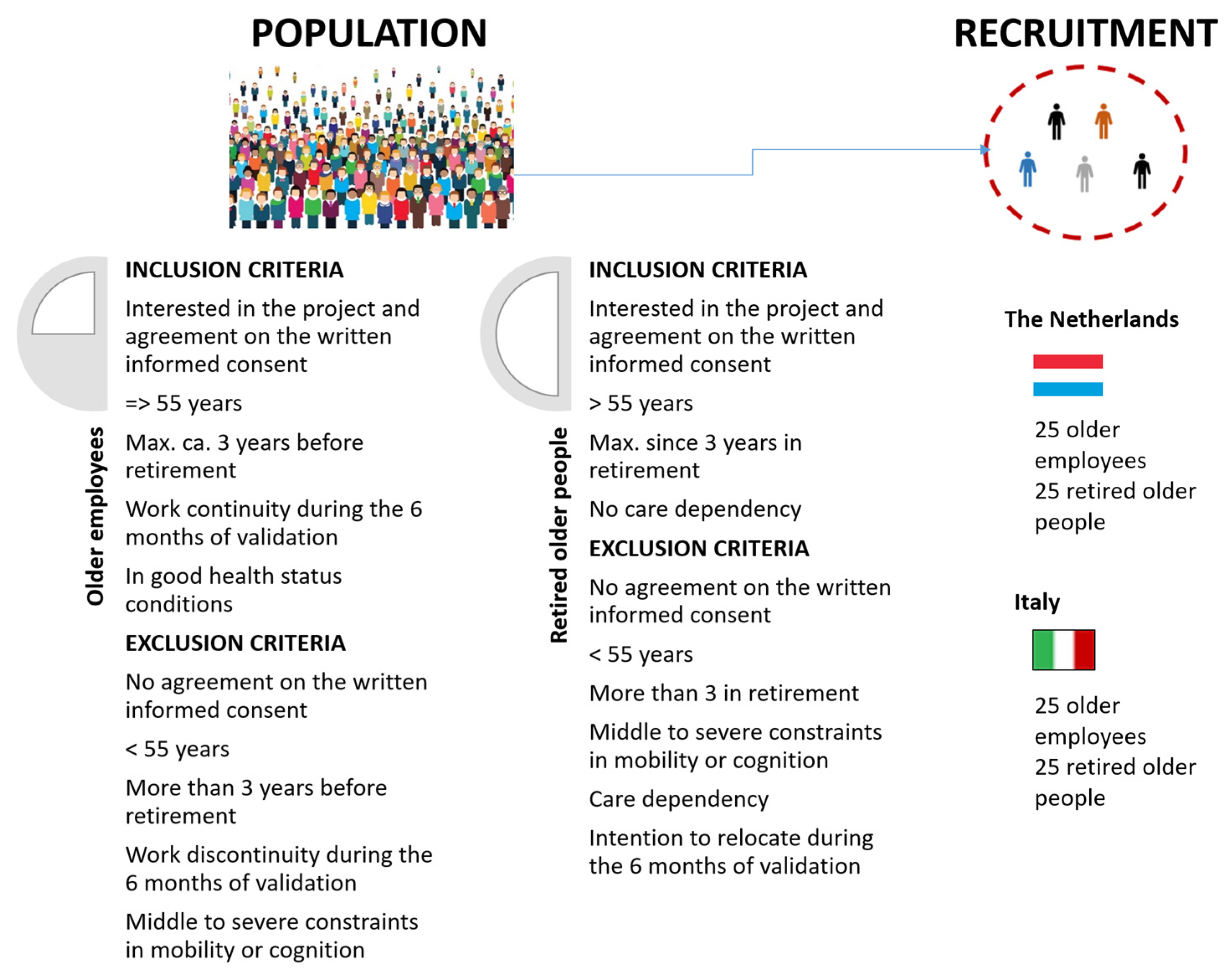

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Recruitment Procedure

2.2.2. QUANT and QUAL Data Collection Tools

2.2.3. QUANT and QUAL Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. The Impact of the AgeWell DC in Improving Healthy Ageing Dimensions

3.3. Users’ Experience with the AgeWell Digital Coach

3.4. Strengths and Weaknesses of the System

- Motivating users to increase their physical activity frequency and regularity: “I have had some benefits, for example from walking. Doing it for an hour a day at a steady pace is good for your health and the app makes me fulfill this commitment” (IT1, M, 65, retiree);

- Reminding them to perform activities: “I’m mainly using it as a reminder: it reminds me when I have to do something, some things I honestly do when the app reminds me” (IT3, M, 70, retiree);

- Helping users focus on their own needs (physical, psychological and social): “I have found the app very useful in helping me to focus a little on myself. In fact, I have a tendency to be focused on the needs of others, so someone reminding me “What do you do for yourself?” seems useful” (IT4, F, 65, retiree);

- Stimulating the activities proposed under the realms of mental well-being; some of them thought that several activities were really inspiring, e.g., activities about memories, photographs, yoga and relaxation exercises, or writing down their own qualities: “The app gave me inspiration to call my aunt and ask her to fix and rewrite her recipes. There are so many things that can be taken into account, maybe different from what we do every day” (IT7, M, 69, retiree). This opinion was common, especially among Italian respondents, while Dutch participants mentioned that they liked the proposed activities, but with great variety in the different healthy ageing realms, not only related to emotional well-being but with a wider perspective on the system empowerment capability: “I liked the assignment of being happy with things you have in your home, sending a card to family/friends, the reminder to do some volunteer work, plants” (NL32); “It fits well into my discipline, gives me inspiration and motivation” (NL5);

- Promoting a good retirement process: “It might be helpful for people in danger of falling into a void after retiring” (NL5) and “The digital coach managed to give me the motivation during the day or week to organize myself with new ideas, because a person who suddenly finds himself without work commitments can feel overwhelmed. The app helps you get organized and above all keeps you physically but also psychologically active, because it helps you organize your day, so for me it is useful by readying me for retirement” (IT10, F, 55, older worker).

- Some physical activities proposed by the system were too physically demanding and not fully appropriate for elderly people, and users could not give reasons for not doing the suggested activities, thereby penalizing the overall rate at the end of the week: “On the other hand, the physical activity part that marks the day is not suitable for us. It is not that we do not move around but, for example, on Sunday we usually go for an excursion because we like to walk, but we have done 2 days of heavy gardening, so yesterday we did not feel like walking” (IT43, F, 59, older worker);

- The system was quite rigid, not customizable and not flexible: “What bothers me is the daily activity that is automatically inserted and that I cannot remove” (IT4, F, 65; retiree) and “Planning is tricky, also because I work part-time. (I would prefer not to have a) split between working and not working (retirement). I am not able to fill the day because of work, and my activities like walking dogs and dog training do not fit in (the app)” (NL038);

- The constant pressure the DC put on users by asking them to report the performance was unpleasant: “I would prefer it to be an inspiration tool, not an administration tool” (NL4).

- Problems in registering/changing the activities they had done. Dutch participants also complained about the long time the platform took to load and the pop-up that mentioned “attempts”;

- Problems with the daily plan, finding it annoying, and preferring a weekly and personalized plan: “I thought it would also be easier and more intuitive to record the activities carried out so that the activity icons in the various sections would be colored. You have to go and click on “I have done it”, but there was one time when it did not record it and I had to go back to it” (IT03, M, 70, retiree);

- The lack of intuitiveness and flexibility: “The logic of the app is not good. It is unpleasant to work with, not user friendly. (This is an) important downside” (NL027);

- The unclearness of graphs reporting daily activity rates: “Overview of notifications is missing in the app. It is tricky that you cannot fill in anything for the day before. Planning something extra on the day itself is not possible” (NL035);

- The avatar was annoying and boring (especially for Italian users), and it had no added value, especially for Dutch users. The latter found the way it looked and sounded not fun and very negative because the avatar repeated messages many times, and it was not interactive. The voice of the avatar was deemed unpleasant and sometimes boring: “Remarks like ‘doing the dishes and cleaning up works well for me’, reminders and specifically derogatory comments like ‘keep it up’ were fake” (NL014).

- Personalize activities as much as possible, including by adding other activities such as reading, volunteering and nutrition: “The reading activity does not seem so much specified by the app, maybe less in summer, but in winter it would be better to add it and maybe the app should be diversified on a seasonal basis, in my opinion” (IT9, M, 61, retiree), and “To add other activities”, e.g., volunteering (NL10), nutrition (NL04), gym (NL036);

- Plan periodical meetings with the human coach: “I suggest that every now and then there is a confrontation with the coach, that is, a contact or a video call or a physical meeting (…) I believe that a tool of this kind can be useful, but it must be interspersed with personal relationships, not even with videoconferencing, rather private talk, once with a psychologist, once with a trainer, another time with an expert of any another thing, because it is the relationship that gives us the opportunity to grow, to improve, in my opinion, in terms of both physical and psychological well-being” (IT52,F, 69, retiree);

- Explaining what every proposed activity is useful for in order to further motivate the user to do it: “I could not lend myself to really doing those categories or activities, when I do not know what it is useful for. What does it bring me?” (NL11).

- Make the app more intuitive: “If there was some more automatic and intuitive function, it would be better, because you always have to go there, see if it works, wait for it to turn and load” (IT03, M, 70, retiree);

- Launch activities with movies and videos to motivate people to perform the activities: “It would be a good idea to start with a movie clip (that) begins with explaining why I should do this activity” (NL11);

- Connect the app activity plan to the smartphone agenda: “The app should link to the agenda on your phone” (ID4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Towards Tailored and Attractive Digital Coach Systems

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marmot, M.; Wilkinson, R.G. Health and the Psychosocial Environment at Work. In Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Strasbourg, France, 2006; ISBN 13: 9780198565895. [Google Scholar]

- Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Brzyski, P. Psychosocial work conditions as predictors of quality of life at the beginning of older age. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2005, 18, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, A.R.; Daniel, F.; Guadalupe, S.; Massano-Cardoso, I.; Vicente, H. Time spent in retirement, health and well-being. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, 339–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Aging and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9789240694811. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Farré, C.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Bonmatí-Tomàs, A.; Malagón-Aguilera, M.C.; Gelabert-Vilella, S.; Fuentes-Pumarola, C.; Juvinyà-Canal, D. Prevalence and related factors of Active and Healthy Aging in Europe according to two models: Results from the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Green Paper on Aging. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/1_en_act_part1_v8_0.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Atchley, R.C. A continuity theory of normal ageing. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atchley, R.C. Social Forces and Aging, 9th ed.; Wadsworth Publishing: Belmont, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 9780534043384. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, G.; Stenling, A.; Bielak, A.A.; Bjälkebring, P.A.; Gow, J.; Kivi, M.; Muniz-Terrera, G.; Boo, J.B.; Lindwall, M. Towards an active and happy retirement? Changes in leisure activity and depressive symptoms during the retirement transition. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; O’Brien, N.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F.F. Changes in physical activity during the retirement transition: A theory-based, qualitative interview study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Longitudinal changes in physical activity and sedentary time in adults around retirement age: What is the moderating role of retirement status, gender and educational level? BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socci, M.; Santini, S.; Dury, S.; Perek-Białas, J.; D’Amen, B.; Principi, A. Physical Activity during the Retirement Transition of Men and Women: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 30, 2720885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziej, I.W.K.; García-Gómez, P. Saved by retirement: Beyond the mean effect on mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 225, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolever, R.Q.; Simmons, L.A.; Sforzo, G.A.; Dill, D.; Kaye, M.; Bechard, E.M.; Southard, M.E.; Kennedy, M.; Vosloo, J.; Yang, N. A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: Defining a key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner-Jehle, S.; Schmid, M.; Grüninger, U. The “Health Coaching” programme: A new patient-centred and visually supported approach for health behaviour change in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Willard-Grace, R.; Ghorob, A. Expanding the roles of medical assistants: Who does what in primary care? JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1025–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, A.; Cameron, P.; Flicker, L.; Arendts, G.; Brand, C.; Etherton-Beer, C.; Forbes, A.; Haines, T.; Hill, A.; Hunter, P.; et al. Evaluation of RESPOND, a patient-centred program to prevent falls in older people presenting to the emergency department with a fall: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.; Gilburt, H. Supporting People to Manage Their Health: An Introduction to Patient Activation London; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/supporting-people-manage-health-patient-activation-may14.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Stara, V.; Santini, S.; Kropf, J.; D’Amen, B. Digital Health Coaching Programs Among Older Employees in Transition to Retirement: Systematic Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e25065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, R.; Casaccia, S.; Cortellessa, G.; Astell, A.; Lattanzio, F.; Corsonello, A.; D’Ascoli, P.; Paolini, S.; Di Rosa, M.; Rossi, L.; et al. Coaching Through Technology: A Systematic Review into Efficacy and Effectiveness for the Ageing Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTear, M. Conversational AI: Dialogue systems, conversational agents, and chatbots. In Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 13, pp. 1–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, E.; Kari, T.; Frank, L. Digital Coaching Motivating Young Elderly People towards Physical Activity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nurs. Res. 1991, 40, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Niehaus, L. Mixed Method Design: Principles and Procedures, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.C. Preserving Distinctions within the Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Merger; Hesse-Biber, S., Burke Johnson, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schoonenboom, J.; Johnson, R.B. How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design. Koln. Z. Fur Soziologie Und Soz. 2017, 69, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe—Statistics on Working and Moving into Retirement. Eurostat Statistics Explained. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_working_and_moving_into_retirement#Older_people_moving_into_retirement (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Ware, J., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Wellbeing Measures in Primary Health Care/The Depcare Project; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/349766 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Rompell, M.; Herrmann, C.; Wachter, R.; Edelmann, F.; Pieske, B.; Grande, G. A short form of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE-6): Development, psychometric properties and validity in an intercultural non-clinical sample and a sample of patients at risk for heart failure. Psychosoc. Med. 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubben, J. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam. Community Health J. Health Promot. Maint. 1988, 11, 42–52. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44953053 (accessed on 2 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lubben, J.; Blozik, E.; Gillmann, G.; IIiffe, S.; von Renteln Kruse, W.; Beck, J.C.; Stuck, A.E. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European Community–dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Summary Scales, 2nd ed.; The Health Institute, New England Medical Center: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. Usability Evaluation in Industry, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz, B.; Schrepp, M.; Held, T. Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In HCI and Usability for Education and Work; Symposium of the Austrian HCI and Usability Engineering Group: Walldorf, Germany, 2008; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, L.; Ugarriza, D.N. The Concept of Theme as Used in Qualitative Nursing Research. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2000, 22, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Bondas, T.; Turunen, H. Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis: Implications for Conducting a Qualitative Descriptive Study. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plat, S. Thematic Analysis Software: How It Works & Why You Need It. Available online: https://getthematic.com/insights/thematic-analysis-software/ (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Moretti, F.; van Vliet, L.; Benzing, J.; Deledda, G.; Mazzi, M.; Rimondini, M.; Zimmermann, C.; Fletcher, I. A standardized approach to qualitative analysis of focus group discussions from different countries. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 82, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing paradigm in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevin, E.; Sines, D. Enhancing the truthfulness, consistency, and transferability of a qualitative study: Using a manifold of approaches. Nurse Res. 2000, 7, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.; Greenhalgh, T. Coping with complexity: Educating for capability. BMJ 2001, 323, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Rigor or rigor mortis: The problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1993, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornbluh, M. Combatting challenges to establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2015, 12, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culley, J.; Herman, J.; Smith, D.; Tavakoli, A. Effects of technology and connectedness on community-dwelling older adults. Online J. Nurs. Inform. 2013, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Quan-Haase, A.; Mo, G.Y.; Wellman, B. Connected seniors: How older adults in East York exchange social support online and offline. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.S.; Shillair, R.; Cotton, S.R.; Winstead, V.; Yost, E. Getting grandma online: Are tablets the answer for increasing inclusion for older adults inthe U.S.? Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, S.; Galassi, F.; Kropf, J.; Stara, V. A digital coach promoting healthy aging among older adults in transition to retirement: Results from a qualitative study in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanvatkar, S.; Kankanhalli, A.; Rajan, V. User models for personalized physical activity interventions: Scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Poole, M.S. What is personalization? Perspectives on the design and implementation of personalization in information systems. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2006, 16, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocaballi, A.B.; Berkovsky, S.; Quiroz, J.C.; Laranjo, L.; Tong, H.L.; Rezazadegan, D.; Briatore, A.; Coiera, E. The personalization of conversational agents in health care: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e15360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.L.; Yabroff, K.R.; Meekins, A.; Topor, M.; Lamont, E.B.; Brown, M.L. Evaluation of Trends in the Cost of Initial Cancer Treatment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viviani, C.A.; Bravo, G.; Lavallière, M.; Arezes, P.M.; Martínez, M.; Dianat, I.; Bragança, S.; Castellucci, H.I. Productivity in older versus younger workers: A systematic literature review. Work 2021, 68, 577–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faramarzi, A.; Javan-Noughabi, J.; Tabatabaee, S.S.; Najafpoor, A.A.; Rezapour, A. The lost productivity cost of absenteeism due to COVID-19 in health care workers in Iran: A case study in the hospitals of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021, 21, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Goštautaitė, B.; Wang, M.; Ng, T.W.H. Age and sickness absence: Testing physical health issues and work engagement as countervailing mechanisms in a cross-national context. Pers. Psychol. 2021, 75, 895–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The 2021 Ageing Report. Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Recruited Participants | Drop-Out Pre-Trial | Drop-Out during the Trial | Total Drop-Outs | Invalid Questionnaires | Total Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 53 | 7 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 34 |

| The Netherlands | 38 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 28 |

| Total | 91 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 6 | 62 |

| All (n = 62) | Italy (n = 34) | The Netherlands (n = 28) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 22 (35.5) | 19 (55.9) | 3 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Male | 40 (64.5) | 15 (44.1) | 25 (89.3) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/in couple | 47 (75.8) | 23 (67.6) | 24 (85.7) | 0.342 |

| Single | 5 (8.1) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (7.1) | |

| Divorced/separated | 6 (9.7) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (3.6) | |

| Widowed | 4 (6.5) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (3.6) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary school (1–5 years of education) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Secondary school (6–8 years of education) | 5 (8.1) | 5 (14.7) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| High school (9–13 years of education) | 28 (45.2) | 21 (61.8) | 7 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Bachelor’s degree (more than 13 years of education) | 29 (46.8) | 8 (23.5) | 21 (75.0) | <0.001 |

| Working condition | ||||

| Older workers | 23 (36.1) | 12 (33.3) | 11 (39.3) | 0.629 |

| Retirees | 39 (63.9) | 22 (66.7) | 17 (60.7) |

| Healthy Ageing Dimensions | T0 (N = 62) | T1 (N = 52) | T2 (N = 49) | p (T0 vs. T1) | p (T0 vs. T2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| SF-12v2 | |||||

| PCS ≤ 50, n (%) | 11 (19.6) | 12 (23.1) | 15 (30.6) | 0.002 | 0.055 |

| MCS < 42, n (%) | 8 (14.3) | 6 (11.5) | 7 (14.3) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Level of physical activity (IPAQ-SF) | 0.012 | 0.142 | |||

| Low | 5 (8.2) | 3 (6.0) | 4 (8.3) | ||

| Medium | 25 (41.0) | 19 (38.0) | 17 (35.4) | ||

| High | 31 (50.8) | 28 (56.0) | 27 (56.3) | ||

| Mental well-being (WHO-5) | 13.4 ± 4.6 | 13.5 ± 4.5 | 12.9 ± 3.9 | 0.545 | 0.897 |

| Self-efficacy (GSE-6) | 15.0 ± 3.4 | 15.4 ± 2.8 | 14.8 ± 3.1 | 0.561 | 0.473 |

| Lubben < 12, n (%) | 13 (22.0) | 13 (25.0) | 12 (24.5) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Outcome Variables | T1 At 5 Weeks of System Usage July 2021 (N = 52) | T2 At 10 Weeks of System Usage September (N = 49) |

|---|---|---|

| (±SD) | (±SD) | |

| User experience (UEQ) | ||

| Attractiveness | 0.58 ± 1.17 | 0.54 ± 1.18 |

| Perspicuity | 0.91 ± 1.29 | 1.22 ± 1.02 |

| Efficiency | 0.31 ± 1.25 | 0.50 ± 1.22 |

| Dependability | 0.73 ± 0.82 | 0.48 ± 0.95 |

| Stimulation | 0.40 ± 1.25 | 0.34 ± 1.22 |

| Novelty | 0.43 ± 1.27 | 0.43 ± 1.29 |

| Usability of the virtual coach (SUS) | 59.0 ± 14.5 | 59.6 ± 14.1 |

| N(%) | N(%) | |

| Impact of the virtual coach in the following activities “Moderately/very/extremely useful” | ||

| Advice on physical exercise to practice at home | 34 (65.4) | 26 (54.2) |

| Motivating to get in nature and practice physical activity | 36 (69.2) | 28 (58.3) |

| Suggestions for mental well-being | 33 (63.5) | 25 (52.1) |

| Suggestions for leisure | 31 (59.6) | 24 (50.0) |

| Triggering curiosity and interests | 34 (65.4) | 27 (56.3) |

| Suggestions for keeping in contact with friends and relatives | 27 (51.9) | 22 (45.8) |

| Suggestions for approaching retirement smoothly | 26 (50.0) | 26 (54.2) |

| Enriching my free time | 35 (67.3) | 26 (54.2) |

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| 1. Digital coach’s contents’ strengths | (a) Improving physical activity |

| (b) Reminding | |

| (c) Helping self to self-focus | |

| (d) Improving psychological/social well-being | |

| (e) Enhancing healthy ageing (especially during the transition to retirement) | |

| 2. Digital coach’s contents’ weaknesses | (a) Some physical activities are not appropriate for older people |

| (b) No flexible/personalized activities | |

| (c) Too much pressure from the digital coach | |

| 3. Human coach’s role | (a) Useful periodical meetings |

| 4. Digital coach’s technical strengths | (a) Video tutorials |

| 5. Digital coach’s technical weaknesses | (a) Problems in registering/changing new activities done |

| (b) Planning timeframe | |

| (c) Lack of intuitiveness and flexibility | |

| (d) Unclearness of graphs reporting daily activity rates | |

| (e) The avatar | |

| 6. Suggestions on contents | (a) Function/activity personalization |

| (b) Periodical meetings with a human coach | |

| (c) Explaining the objective of the proposed activities | |

| 7. Suggestions on technical aspects | (a) Making more intuitive |

| (b) Launching activities with movies | |

| (c) Connecting app activities agenda to smartphone agenda |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santini, S.; Fabbietti, P.; Galassi, F.; Merizzi, A.; Kropf, J.; Hungerländer, N.; Stara, V. The Impact of Digital Coaching Intervention for Improving Healthy Ageing Dimensions among Older Adults during Their Transition from Work to Retirement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054034

Santini S, Fabbietti P, Galassi F, Merizzi A, Kropf J, Hungerländer N, Stara V. The Impact of Digital Coaching Intervention for Improving Healthy Ageing Dimensions among Older Adults during Their Transition from Work to Retirement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054034

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantini, Sara, Paolo Fabbietti, Flavia Galassi, Alessandra Merizzi, Johannes Kropf, Niklas Hungerländer, and Vera Stara. 2023. "The Impact of Digital Coaching Intervention for Improving Healthy Ageing Dimensions among Older Adults during Their Transition from Work to Retirement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054034

APA StyleSantini, S., Fabbietti, P., Galassi, F., Merizzi, A., Kropf, J., Hungerländer, N., & Stara, V. (2023). The Impact of Digital Coaching Intervention for Improving Healthy Ageing Dimensions among Older Adults during Their Transition from Work to Retirement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054034