The Impact of Women’s Agency on Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Focused Question

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

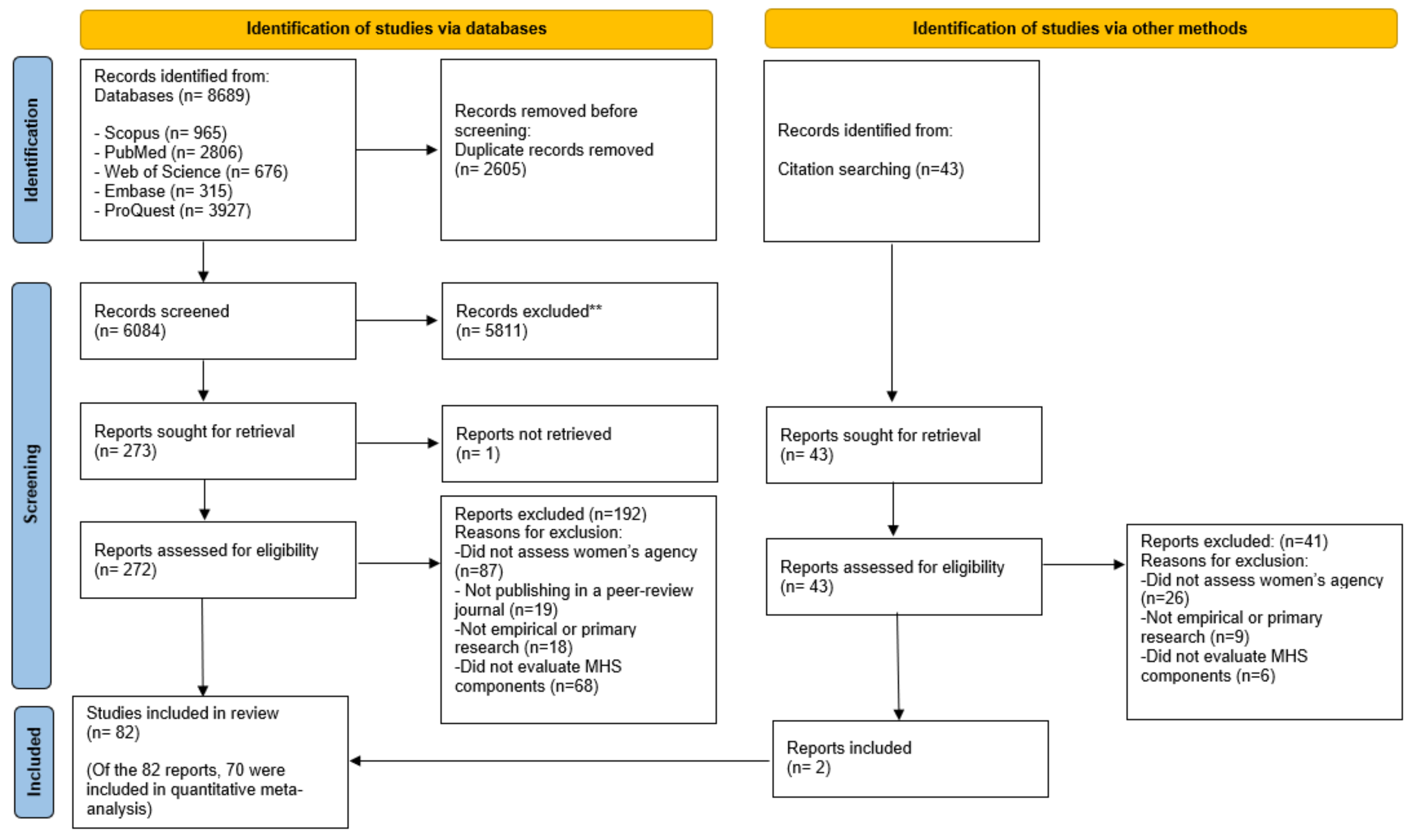

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Dimensions and Domains of Indicators of Women’s Agency

3.3. Quantitative Meta-Analysis

3.4. Synthesis: The Associations between Indicators of Women’s Agency and MHS Outcomes

- Skilled ANC: receiving any antenatal care from a skilled healthcare provider including a midwife, doctor, nurse, or from all three.

- Timing of the first ANC visit: receiving the first antenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy.

- Receiving at least one ANC visit: receiving at least one antenatal visit during the most recent pregnancy.

- Receiving more than four ANC visits: receiving more than four antenatal visits during the most recent pregnancy.

- Receiving more than eight ANC visits: receiving more than eight antenatal visits during the most recent pregnancy.

- Facility-based delivery: giving birth at any health center, includ-ing a hospital, health clinic, or maternity clinic.

- Skill birth attendant: having a skilled healthcare provider for the most recent childbirth, including a midwife, doctor, or nurse, who has been trained in the skills needed to manage pregnancy and childbirth for the most recent childbirth.

- Receiving postnatal care: utilization of postnatal care by a skilled healthcare provider within the first 42 days after delivery for the most recent childbirth.

3.4.1. Women’s Agency and Accessing Skilled ANC

3.4.2. Women’s Agency and Initiating the First ANC Visit during the First Trimester of Pregnancy

3.4.3. Women’s Agency and Receiving at Least One ANC Visit

3.4.4. Women’s Agency and Receiving More Than Four ANC Visits

3.4.5. Women’s Agency and Receiving More Than Eight ANC Visits

3.4.6. Women’s Agency and FBD

3.4.7. Women’s Agency and Having SBA

3.4.8. Women’s Agency and Received PNC

3.4.9. Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Indicators and Indexes Used to Measure Women’s Agency

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Oraganization. Maternal Mortality 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- World Health Oraganization. Maternal Morbidity and Well-Being 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/maternal-health/maternal-morbidity-and-well-being (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Addisu, D.; Mekie, M.; Melkie, A.; Abie, H.; Dagnew, E.; Bezie, M.; Degu, A.; Biru, S.; Chanie, E.S. Continuum of maternal healthcare services utilization and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Womens Health 2022, 18, 17455057221091732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkema, L.; Chou, D.; Hogan, D.; Zhang, S.; Moller, A.-B.; Gemmill, A.; Fat, D.M.; Boerma, T.; Temmerman, M.; Mathers, C.; et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: A systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet 2016, 387, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, D.; Daelmans, B.; Jolivet, R.R.; Kinney, M.; Say, L. Ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirths. BMJ 2015, 351, h4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience: Summary 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259947/WHO-RHR-18.02-eng.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Tunçalp, Ö.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Lawrie, T.; Bucagu, M.; Oladapo, O.T.; Portela, A.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience-going beyond survival. Bjog 2017, 124, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benova, L.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moran, A.C.; Campbell, O.M.R. Not just a number: Examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Oraganization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Carefor a Positive Pregnancy Experience 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241549912 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Kyei-Nimakoh, M.; Carolan-Olah, M.; McCann, T.V. Access barriers to obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa-a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality: Fact Sheet: To Improve Maternal Health, Barriers that Limit Access to Quality Maternal Health Services Must Be Identified and Addressed at All Levels of the Health System. 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112318?show=full (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Finlayson, K.; Downe, S. Why Do Women Not Use Antenatal Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathalla, M.F. Human rights aspects of safe motherhood. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 20, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajedinejad, S.; Majdzadeh, R.; Vedadhir, A.; Tabatabaei, M.G.; Mohammad, K. Maternal mortality: A cross-sectional study in global health. Glob. Health 2015, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.E.; Rahman, M.; Mostofa, M.G.; Zahan, M.S. Reproductive health care utilization among young mothers in Bangladesh: Does autonomy matter? Womens Health Issues 2012, 22, e171–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibre, G.; Zegeye, B.; Yeboah, H.; Bisjawit, G.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Yaya, S. Women empowerment and uptake of antenatal care services: A meta-analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys from 33 Sub-Saharan African countries. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, M.; Hameed, W.; Saleem, S. Do empowered women receive better quality antenatal care in Pakistan? An analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkianti, A.; Afifah, T.; Saptarini, I.; Rakhmadi, M.F. Women’s decision-making autonomy in the household and the use of maternal health services: An Indonesian case study. Midwifery 2020, 90, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, M.; Gubhaju, B. Women’s status, household structure and the utilization of maternal health services in Nepal. Asia-Pac. Popul. J. 2001, 16, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James-Hawkins, L.; Peters, C.; VanderEnde, K.; Bardin, L.; Yount, K.M. Women’s agency and its relationship to current contraceptive use in lower-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the literature. Glob. Public Health 2018, 13, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, Z.; Salway, S. ‘I never go anywhere’: Extricating the links between women’s mobility and uptake of reproductive health services in Pakistan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1751–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokharel, A.; Pokharel, S.D. Women’s involvement in decision-making and receiving husbands’ support for their reproductive healthcare: A cross-sectional study in Lalitpur, Nepal. Int. Health 2022, 15, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obasohan, P.E.; Gana, P.; Mustapha, M.A.; Umar, A.E.; Makada, A.; Obasohan, D.N. Decision Making Autonomy and Maternal Healthcare Utilization among Nigerian Women. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2019, 8, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corroon, M.; Speizer, I.S.; Fotso, J.-C.; Akiode, A.; Saad, A.; Calhoun, L.; Irani, L. The role of gender empowerment on reproductive health outcomes in urban Nigeria. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmed, F. Women’s empowerment and practice of maternal healthcare facilities in Bangladesh: A trend analysis. J. Health Res. 2021, 36, 1104–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatiwada, J.; Muzembo, B.A.; Wada, K.; Ikeda, S. Dimensions of women’s empowerment on access to skilled delivery services in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrysch, S.; McMahon, S.A.; Siling, K.; Kenward, M.G.; Campbell, O.M.R. Autonomy dimensions and care seeking for delivery in Zambia; The prevailing importance of cluster-level measurement. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, S.S.; Wypij, D.; Das Gupta, M. Dimensions of women’s autonomy and the influence on maternal health care utilization in a North Indian City. Demography 2001, 38, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.; Muralidharan, A.; Pappa, S. A review of measures of women’s empowerment and related gender constructs in family planning and maternal health program evaluations in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratley, P. Associations between quantitative measures of women’s empowerment and access to care and health status for mothers and their children: A systematic review of evidence from the developing world. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassahun, A.; Zewdie, A. Decision-making autonomy in maternal health service use and associated factors among women in Mettu District, Southwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.-B.; Daniels, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Temmerman, M.; Alkema, L. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, A.B.; Petzold, M.; Chou, D.; Say, L. Early antenatal care visit: A systematic analysis of regional and global levels and trends of coverage from 1990 to 2013. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e977–e983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schünemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ. Int. 2018, 121 Pt 1, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane, L.; Thomas, T.; Ye, C.; Paul, J. Posing the research question: Not so simple. Can. J. Anaesth. 2009, 56, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.; Shah, K.; Phillips, A.W.; Hartman, N.; Love, J.; Gottlieb, M. Use of the “Step-back” Method for Education Research Consultation at the National Level: A Pilot Study. AEM Educ. Train. 2019, 3, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, M.; Dehon, E.; Jordan, J.; Bentley, S.; Ranney, M.L.; Lee, S.; Khandelwal, S.; Santen, S.A. Getting Published in Medical Education: Overcoming Barriers to Scholarly Production. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018: User Guide; Department of Family Medicine, McGuill Univertiy: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.J.; Zwahlen, M.; Egger, M.; Higgins, J.P. Meta-Analysis in Stata. In Systematic Reviews in Health Research: Meta-Analysis in Context; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 481–509. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Chu, H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2018, 74, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins JPT GSe. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0, [updated March 2011]; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, F.O.; Musoke, P.; Kwena, Z.; Owino, G.O.; Bukusi, E.A.; Darbes, L.; Turan, J.M. The role of women’s empowerment and male engagement in pregnancy healthcare seeking behaviors in western Kenya. Women Health 2019, 59, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, A.I.; Ghose, B.; Rahman, M.M. Relationship between maternal healthcare utilisation and empowerment among women in Bangladesh: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e049167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, T.R.; Kutty, V.R.; Sarma, P.S.; Dangal, G. Safe delivery care practices in western Nepal: Does women’s autonomy influence the utilization of skilled care at birth? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemicael, G. Do women with higher autonomy seek more maternal health care? Evidence from Eritrea and Ethiopia. Health Care Women Int. 2010, 31, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, M.; Salway, S. Women’s position within the household as a determinant of maternal health care use in Nepal. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 2006, 32, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sado, L.; Spaho, A.; Hotchkiss, D.R. The influence of women’s empowerment on maternal health care utilization: Evidence from Albania. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 114, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Lama, G.; Lee, H. Effect of women’s empowerment on their utilization of health services: A case of Nepal. Int. Soc. Work 2012, 55, 554–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamoto, K.; Gipson, J.D. Examining the mechanisms by which women’s status and empowerment affect skilled birth attendant use in Senegal: A Structural Equation Modeling approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, N.; Hamid, A.; Akram, M. Role of women empowerment in utilization of materna lhealthcare services: Evidence from Pakistan. Pak. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2019, 57, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuru, R.R. The influence of women empowerment on maternal and childcare use in Nigeria. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 14, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Sahni, B.; Jena, P.K. Education, employment, economic status and empowerment: Implications for maternal health care services utilization in India. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, W.T.; Burgard, S.A. Couples’ reports of household decision-making and the utilization of maternal health services in Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2403–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Jeong, H.-S. The role of women’s autonomy and experience of intimate partner violence as a predictor of maternal healthcare service utilization in Nepal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagu, D.; Sudhinaraset, M.; Diamond-Smith, N.; Campbell, O.; Gabrysch, S.; Freedman, L.; E Kruk, M.; Donnay, F. Where women go to deliver: Understanding the changing landscape of childbirth in Africa and Asia. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripad, P.; Warren, C.E.; Hindin, M.J.; Karra, M. Assessing the role of women’s autonomy and acceptability of intimate-partner violence in maternal health-care utilization in 63 low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1580–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Ma, N. The effect of women’s decision-making power on maternal health services uptake: Evidence from Pakistan. Health Policy Plan. 2013, 28, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, L.M.P.; Khan, S.; Moore, J.E.; Timmings, C.; van Lettow, M.; Vogel, J.P.; Khan, D.N.; Mbaruku, G.; Mrisho, M.; Mugerwa, K.; et al. Low-and middle-income countries face many common barriers to implementation of maternal health evidence products. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 76, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Creanga, A.A.; Gillespie, D.G.; Tsui, A.O. Economic status, education and empowerment: Implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokam, B.; Zamo Akono, C. The association between women’s empowerment and reproductive health care utilization in Cameroon. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2022, 34, mzac032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, F.; Oni, F.A.; Sharafat Hossen, S. Does gender inequality matter for access to and utilization of maternal healthcare services in Bangladesh? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chol, C.; Negin, J.; Agho, K.E.; Cumming, R.G. Women’s autonomy and utilisation of maternal healthcare services in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries: Results from the demographic and health surveys, 2010–2016. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, M.V.; Kerr, R.B.; Hoddinott, J.; Garigipati, P.; Olmos, S.; Young, S.L. Role of women’s Empowerment in child nutrition outcomes: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 1138–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.-H.; Hoang, V.; Nguyen, K.T.-B. Are empowered women more likely to deliver in facilities? An explorative study using the Nepal demographic and health survey 2011. Int. J. Matern. Child Health 2014, 2, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamor, P.E.; Grady, C. Women’s autonomy in health care decision-making in developing countries: A synthesis of the literature. Int. J. Women’s Health 2016, 8, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmeades, J.; Hinson, L.; Sebany, M.; Murithi, L. A Conceptual Framework for Reproductive Empowerment: Empowering Individuals and Couples to Improve Their Health; International Center for Research on Women: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, A.; Pratley, P.; Alkire, S. Measuring women’s autonomy in Chad using the relative autonomy index. Fem. Econ. 2016, 22, 264–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yount, K.M.; Peterman, A.; Cheong, Y.F. Measuring women’s empowerment: A need for context and caution. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizheh, M.; Muhidin, S.; Behboodi Moghadam, Z.; Zareiyan, A. Women empowerment in reproductive health: A systematic review of measurement properties. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, J.; Rafail, P. Measurement models of women’s autonomy using the 1998/1999 India DHS. J. Popul. Res. 2013, 30, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darteh, E.K.M.; Dickson, K.S.; Doku, D.T. Women’s reproductive health decision-making: A multi-country analysis of demographic and health surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstone, S.R. Women’s empowerment, household status and contraception use in Ghana. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2017, 49, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, A.A.; Ruark, A.; Tan, J.Y. Re-conceptualising gender and power relations for sexual and reproductive health: Contrasting narratives of tradition, unity, and rights. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 22 (Suppl. S1), 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Mishra, A.; Prakash, A.; Singh, C.; Qaisrani, A.; Poonacha, P.; Vincent, K.; Bedelian, C. A qualitative comparative analysis of women’s agency and adaptive capacity in climate change hotspots in Asia and Africa. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mganga, A.E.; Renju, J.; Todd, J.; Mahande, M.J.; Vyas, S. Development of a women’s empowerment index for Tanzania from the demographic and health surveys of 2004-05, 2010, and 2015-16. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2021, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | |

|---|---|

| Is the research question feasible? |

|

| Is it interesting? |

|

| Is it novel? |

|

| Is it ethical? |

|

| Is it relevant? |

|

| Population | women OR female OR girl OR gender |

| AND | |

| Exposure | agency OR empowerment OR autonomy OR decision-making OR “healthcare decision making” OR “household decision making” OR “financial decision making” OR “freedom of movement” OR mobility OR “gender equality” OR “gender equity” OR “gender-based violence” OR status OR negotiation OR negotiating OR power OR coercion OR choice OR “bargaining power” |

| AND | |

| Outcome | pregnant OR pregnancy OR maternity OR mothers OR “preconception care” OR “maternal health service” OR “maternal care service” OR maternal OR “maternal health” OR “maternal care” OR “maternal healthcare utilisation” OR “prenatal care” OR “prenatal health” OR childbearing OR obstetrics OR perinatal OR “perinatal health” OR “perinatal care” OR “perinatal health services” OR “perinatal health outcomes” OR “perinatal health indicators” OR “perinatal health status” OR “antenatal care” OR ANC OR “ANC initiation” OR “quality of ANC” OR “antenatal care utilisation” OR “antepartum care” OR “antenatal period” OR “antenatal service” OR “antenatal care visit” OR “antenatal attendance” OR “professional delivery care” OR intrapartum OR birth OR parturition OR delivery OR “delivery care” OR “institutional birth” OR “delivery at health facility” OR “skilled birth attendant” OR “skilled delivery” OR “birth attendance” OR “childbirth” OR “postpartum” OR “postpartum care” OR “postpartum health” OR “postpartum period” OR “postnatal care” OR PNC OR “PNC visit” OR “reproductive health outcomes” OR “reproductive health indicators” OR “health services” OR “health care” OR “health services utilisation” OR “health access” OR “health outcomes” OR “health indicators” OR “health status” OR “quality care” OR “health care quality” |

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Quantitative or mixed methods with a stand-alone quantitative portion | Qualitative or mixed methods without a stand-alone quantitative portion | This allows the comparability of findings across the studies |

| Study setting | Without limitation | N/A | Confining research to specific settings would restrict our knowledge of the available evidence |

| Study population | Women and girls | N/A | Women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who gave birth |

| Language | English | Non-English | The authors speak English |

| Document type | Peer reviewed | Non-peer reviewed; grey literature; posters; conference proceedings; editorials, opinions, theses and dissertations | Excluding grey literature and including peer-reviewed articles ensure high-quality and comparable research |

| Types of research | Primary empirical research or secondary analyses of data | Systematic reviews; protocols | This ensures the comparability of findings across studies and reasonable combining of the data |

| Exposure measure | Assessing at least one component of women’s agency, including decision-making power, freedom of movement, and gender-equitable attitudes | Articles measured other proxies of women’s agency, such as education, socioeconomic status, and demographic characteristics, without assessing any of the three components of women’s agency | Women’s agency may include three components: decision-making power, freedom of movement, and gender equitable attitudes |

| Outcome measure | Examining access to and use of at least one component of MHS according to WHO recommendations | Any healthcare service utilization outcomes except MHS | This systematic review explores the impact of women’s agency on accessing and using MHS |

| Study results | Without limitation | N/A | No restriction was imposed by type of results. Studies with negative, positive, or null associations between women’s agency and access to and use of MHS were included |

| Study Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Study Settings | Number of Studies (Percentage) |

| Bangladesh | 11 (13.4%) |

| Nepal | 10 (12.2%) |

| Pakistan | 8 (9.8%) |

| Nigeria | 8 (9.8%) |

| Ethiopia | 4 (4.9%) |

| Kenya | 4 (4.9%) |

| India | 4 (4.9%) |

| Cameroon | 3 (3.7%) |

| Egypt | 3 (3.7%) |

| Ghana | 3 (3.7%) |

| Tajikistan | 3 (3.7%) |

| Uganda | 3 (3.7%) |

| Guatemala | 1 (1.2%) |

| Indonesia | 1 (1.2%) |

| Guinea | 1 (1.2%) |

| Zambia | 1 (1.2%) |

| Albania | 1 (1.2%) |

| Senegal | 1 (1.2%) |

| Multi-country | 12 (14.6%) |

| Total | 82 (100%) |

| Regions of conducted studies | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 36 (43.9%) |

| South Asia | 32 (39%) |

| Europe and Central Asia | 4 (4.9%) |

| Middle East and North Africa | 3 (3.7%) |

| East Asia and Pacific | 1 (1.2%) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 1 (1.2%) |

| Multi-region | 5 (6.1%) |

| Total | 82 (100%) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional | 82(100%) |

| Data source | |

| Primary data | 18 (22%) |

| Secondary data (DHS) * | 64 (78%) |

| Publication year | |

| ≤1997 | 0 (0) |

| 1998–2002 | 2 (2.4%) |

| 2003–2007 | 3 (3.7%) |

| 2008–2012 | 12 (14.6%) |

| 2013–2017 | 22 (26.8%) |

| 2018–2022 | 43 (52.4%) |

| Measurement Characteristics of Included Studies | |

|---|---|

| Aggregated Measures or Not? | Number (Percentage) |

| Aggregated | 61 (74.4%) |

| Not aggregated | 21 (25.6%) |

| Method of aggregation | |

| Summative index | 39 (47.6%) |

| Exploratory factor analysis | 4 (4.9%) |

| Confirmatory factor analysis | 2 (2.4%) |

| Principal component analysis | 12 (14.6%) |

| Not stated | 4 (4.9%) |

| Type of measures | |

| Single index | 26 (31.7%) |

| Multiple indices/dimensions | 32 (39%) |

| Mixed aggregated and separate indicators | 3 (3.7%) |

| Not aggregated | 21 (25.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vizheh, M.; Rapport, F.; Braithwaite, J.; Zurynski, Y. The Impact of Women’s Agency on Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053966

Vizheh M, Rapport F, Braithwaite J, Zurynski Y. The Impact of Women’s Agency on Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053966

Chicago/Turabian StyleVizheh, Maryam, Frances Rapport, Jeffrey Braithwaite, and Yvonne Zurynski. 2023. "The Impact of Women’s Agency on Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053966

APA StyleVizheh, M., Rapport, F., Braithwaite, J., & Zurynski, Y. (2023). The Impact of Women’s Agency on Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053966