Exploring and Mapping Screening Tools for Cognitive Impairment and Traumatic Brain Injury in the Homelessness Context: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Unrestricted in terms of qualifications of the person administering the screening tool.

- Economical in terms of cost and time resources required.

- Considerations of acceptability to assessors and those being assessed.

- Sensitive and specific to identifying a brain injury or cognitive impairment amongst people accessing homelessness services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of the Research Questions

- What tools or strategies have been employed in the literature for identifying cognitive impairment or brain injury amongst people who are experiencing homelessness?

- Who are the populations being assessed in the literature, and under what circumstances?

- Are there tools that can be administered in non-clinical homelessness service environments, by non-specialist staff, that are sensitive to identifying a likely cognitive impairment or brain injury?

2.2. Identification of Relevant Literature

2.2.1. Search Terms

- Population: people experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

- Concept: identifying cognitive impairment or brain injury.

- Context: assessment, screening, or measurement.

2.2.2. Database Search

2.2.3. Hand Search

2.3. Selection of Studies

2.3.1. Title and Abstract Screening

2.3.2. Full Text Screening

2.4. Data Mapping

2.5. Collation, Summary, and Report of Results

3. Results

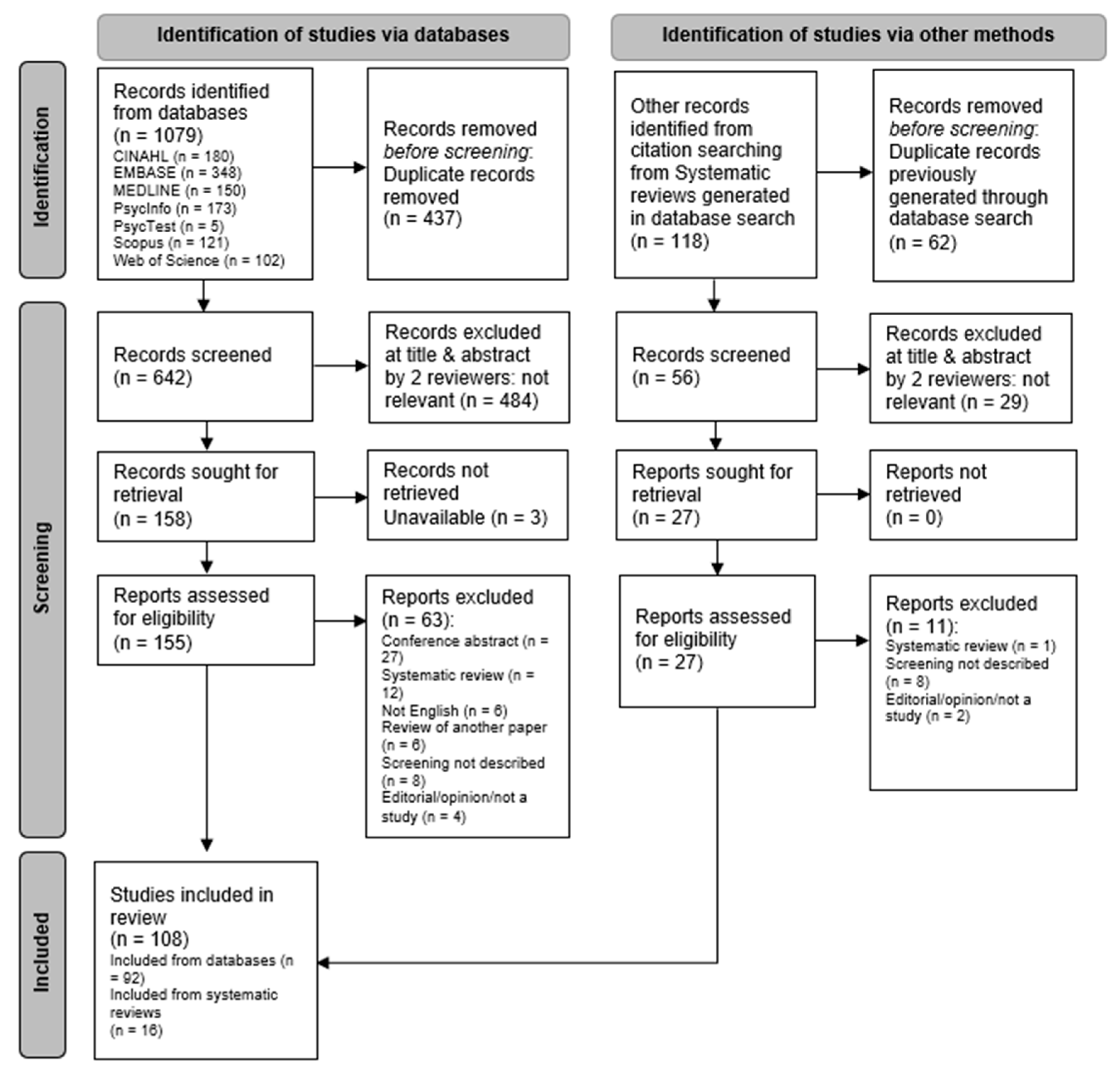

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Extracting and Charting

3.2.1. Populations and Contexts

3.2.2. Screening Instruments

3.2.3. Instruments Unrestricted by Qualification

3.2.4. Acceptability of Instrument to Assessors and Consumers

3.2.5. Sensitivity and Specificity

Cognitive Screens

TBI Screens

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cognitive Impairment or ABI | Screening, Interview or Assessment | People Who Are Homeless |

|---|---|---|

| Keyword search terms | Keyword search terms | Keyword search terms |

| (1) brain damage * | (18) screen * | (42) homeless * |

| (2) brain disease * | (19) health screen * | (43) rough sleep * |

| (3) brain disorder * | (20) screen * tool * | (44) sleep * rough * |

| (4) brain injur * | (21) dementia screen * | (45) unsheltered |

| (5) acquire * brain injur * | (22) assessment * | (46) vulnerabl * hous * |

| (6) traumatic brain injur * | (23) health assessment * | (47) crisis hous * |

| (7) head injur * | (24) assessment tool * | (48) crisis accommodation * |

| (8) brain tumor * | (25) dementia assessment * | (49) transition * hous * |

| (9) cogniti * impair * | (26) cogniti * function * assessment * | (50) transition * accommodat * |

| (10) cogniti * dysfunction * | (27) neuropsych * assessment * | (51) halfway hous * |

| (11) cogniti * disorder * | (28) executive function * assessment * | (52) homeless patient * |

| (12) cogniti * disabilit * | (29) case manage * assessment * | (53) marginal * hous * |

| (13) dementia | (30) intake assessment * | (54) homeless * program * |

| (14) cogniti * defici * | (31) cogniti * function * test * | (55) homeless * service * |

| (15) cogniti * defect * | (32) executive function * test * | (56) homeless * support * |

| (16) alcohol related brain injur * | (33) neuropsych * test * | (57) specialist homeless * service * |

| (17) COMBINE WITH OR | (34) dementia test * | (58) going home staying home |

| (35) interview tool * | (59) Supported Accommodation Assistance Program | |

| (36) intake interview * | (60) COMBINE WITH OR | |

| (37) case manage * interview * | ||

| (38) dementia interview * | ||

| (39) instrument * | ||

| (40) assessment instrument * | ||

| (41) COMBINE WITH OR | ||

| (61) COMBINE (17), (41) & (60) WITH AND | ||

Appendix B

| Publications Included in Study | Sample Size | Mean Age | % Male | Population Focus | Setting | Country | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams, C. E., Pantelis, C., Duke, P. J., & Barnes, T. R. (1996). Psychopathology, social and cognitive functioning in a hostel for homeless women. British Journal of Psychiatry, 168(1), 82–86. [87] | 64 | 44 | 0.0% | women only | Crisis/shelter | UK |

|

| Adams, S. M. (2009). Neuropsychological functioning and attrition rates in outpatient substance dependence treatment ProQuest Dissertations Publishing]. [55] | 68 | 45 | 100.0% | SUD | Crisis/shelter | USA |

|

| Adshead, C. D., Norman, A., & Holloway, M. (2019). The inter-relationship between acquired brain injury, substance use and homelessness; the impact of adverse childhood experiences: an interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Disability and rehabilitation, 1–13. [50] | 8 | 41 | 50.0% | co-/multi-morbidity | Health service for homeless people—homeless/A & D service | UK |

|

| Andersen, J., Kot, N., Ennis, N., Colantonio, A., Ouchterlony, D., Cusimano, M. D., & Topolovec-Vranic, J. (2014). Traumatic brain injury and cognitive impairment in men who are homeless. Disability and rehabilitation, 36(26), 2210–2215. [7] | 34 | 58.8 | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| Bacciardi. S., Maremmani, A. G. I., Nikoo, N., Cambioli, L., Shutz, C., Jang, K., Krausz, M. (2017). Is bipolar disorder associated with tramautic brain injury in the homeless? Riv Psichiatr 52(1), 40–46. [88] | 416 | 39.93 | 94.5% | co-/multi-morbidity | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless | Canada |

|

| Barak, Y., & Cohen, A. (2003). Characterizing the elderly homeless: a 10-year study in Israel. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 37(2), 147–155. [89] | 98 | 71.7 | 95.9% | older people | Homeless support without accommodation—homelessness street outreach | Israel |

|

| Barnes, S. M., Russell, L. M., Hostetter, T. A., Forster, J. E., Devore, M. D., & Brenner, L. A. (2015). Characteristics of Traumatic Brain Injuries Sustained Among Veterans Seeking Homeless Services. Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved, 26(1), 92–105. [12] | 229 | 51.8 | 96.1% | Vets | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—homeless service (veterans) | USA |

|

| Barone, C., Yamamoto, A., Richardson, C. G., Zivanovic, R., Lin, D., & Mathias, S. (2019). Examining patterns of cognitive impairment among homeless and precariously housed urban youth. Journal of Adolescence, 72, 64–69. [9] | 44 | 21.5 | 62.8% | young people | Health service for homeless people—homeless + MH | Canada |

|

| Benda, B. B. (2004). Gender Differences in the Rehospitalization of Substance Abusers Among Homeless Military Veterans. Journal of Drug Issues. Vol.34(4), 2004, pp. 723–750. [90] | 625 | 41.2 | 50.4% | Vets MH/SUD | Other health service—health service (veterans) | USA |

|

| Bousman, C. A., Twamley, E. W., Vella, L., Gale, M., Norman, S. B., Judd, P., … Heaton, R. K. (2010). Homelessness and neuropsychological impairment: preliminary analysis of adults entering outpatient psychiatric treatment. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 198(11), 790–794. [91] | 50 | 43 | 56.0% | MH | Mental Health/SUD Treatment Service—Health service (A & D/Psych) | USA |

|

| Bremner, A. J., Duke, P. J., Nelson, H. E., Pantelis, C., & Barnes, T. R. E. (1996). Cognitive function and duration of rooflessness in entrants to a hostel for homeless men. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169(OCT.), 434–439. [92] | 62 | not stated | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | UK |

|

| Brenner, L. A., Hostetter, T. A., Barnes, S. M., Stearns-Yoder, K. A., Soberay, K. A., & Forster, J. E. (2017). Traumatic brain injury, psychiatric diagnoses, and suicide risk among Veterans seeking services related to homelessness. Brain Injury, 31(13/14), 1731–1735. [85] | 309 | 52.3 | 96.1% | Vets MH/SUD | Other health service—Health service (veterans) | USA |

|

| Brocht, C., Sheldon, P., & Synovec, C. (2020). A clinical description of strategies to address traumatic brain injury experienced by homeless patients at Baltimore’s medical respite program. [References]. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation. Vol.65(2), 2020, pp. 311–320. [51] | NA | NA | NA | adults | Health service for homeless people | USA |

|

| Brown, R. T., Kiely, D. K., Bharel, M. & Mitchell, S. L. (2012). Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(1), 16–22. [93] | 247 | 56 | 80.2% | older people | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Brown, R. T., Hemati, K., Riley, E. D., Lee, C. T., Ponath, C., Tieu, L., … Kushel, M. B. (2017). Geriatric Conditions in a Population-Based Sample of Older Homeless Adults. Gerontologist, 57(4), 757–766. [94] | 350 | 58 | 77.1% | older people | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Buhrich, N., Hodder, T., & Teesson, M. (2000). Prevalence of cognitive impairment among homeless people in inner Sydney. Psychiatric Services, 51(4), 520–521. [95] | 204 | 42.6 | 76.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | Australia |

|

| Bymaster, A., Chung, J., Banke, A., Choi, H. J., & Laird, C. (2017). A Pediatric Profile of a Homeless Patient in San Jose, California. Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved, 28(1), 582–595. [13] | 127 | 48 | 68.5% | adults | Health service for homeless people—Homeless medical clinic | USA |

|

| Caplan, B., Schutt, R. K., Turner, W. M., Goldfinger, S. M., & Seidman, L. J. (2006). Change in neurocognition by housing type and substance abuse among formerly homeless seriously mentally ill persons. [References]. Schizophrenia Research. Vol.83(1), 2006, pp. 77–86. [39] | 112 | not stated | 71.2% | MH | Health service for homeless people—homeless health service | USA |

|

| Castaneda, R., Lifshutz, H., Galanter, M., & Franco, H. (1993). Age at onset of alcoholism as a predictor of homelessness and drinking severity. Journal of Addictive Diseases. Vol.12(1), 1993, 65–77. [96] | 50 | 43 | 100.0% | SUD | Mental Health/SUD Treatment Service—Health service (A & D/Psych) | USA |

|

| Chang, F. H., Helfrich, C. A., Coster, W. J., & Rogers, E. S. (2015). Factors associated with community participation among individuals who have experienced homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(9), 11364–11378. [35] | 120 | 48.76 | 61.7% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | USA |

|

| Cotman, A., & Sandman, C. (1997). Cognitive deficits and their remediation in the homeless. Journal of Cognitive Rehabilitation, 15(1), 16–23. [97] | 24 | 30.6 | 54.2% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation—homelessness transitional accomm program | USA |

|

| Dams-O’Connor, K., Cantor, J. B., Brown, M., Dijkers, M. P., Spielman, L. A., & Gordon, W. A. (2014). Screening for Traumatic Brain Injury: Findings and Public Health Implications. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 29(6), 479–489. [52] | 111 | not stated | not stated | adults | other—diverse community settings | USA |

|

| Davidson, D. (2007). Prefrontal cortical function in the adult chronically homeless. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol.68(6-B), 2007, 4170. [98] | 30 | 42 | 50.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Davidson, D., Chrosniak, L., Wanschura, P., & Flinn, J. (2014). Indications of Reduced Prefrontal Cortical Function in Chronically Homeless Adults. Community Mental Health Journal, 50(5), 548–552. [30] | 46 | 42 | 50.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Distefano, R. (2020). Autonomy support in parents and young children experiencing homelessness: A mixed method approach. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. Vol.81(9-A), 2020. [99] | 28 | 37.9 | 100.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Duerksen, C. L. (1994). Differences between domiciled and undomiciled men on measures of executive functioning [ProQuest Dissertations Publishing]. [100] | 100 | 28.77 | 6.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Durbin, A., Lunsky, Y., Nisenbaum, R., Hwang, S. W., O’Campo, P., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2018). Borderline Intellectual Functioning and Lifetime Duration of Homelessness among Homeless Adults with Mental Illness. Healthcare Policy, 14(2), 40–46. [101] | 172 | not stated | 65.7% | co-/multi-morbidity | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless | Canada |

|

| Fichter, M. M., & Quadflieg, N. (2005). Three-year course and outcome of mental illness in homeless men—A prospective longitudinal study based on a representative sample. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 255(2), 111–120. [102] | 185 | 45.3 | 100.0% | men only | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—Street outreach | Germany |

|

| Foulks, E. F., McCown, W. G., Duckworth, M., & Sutker, P. B. (1990). Neuropsychological Testing of Homeless Mentally Ill Veterans. Psychiatric Services, 41(6), 672–674. [103] | 30 | 42.2 | 100.0% | MH | Homeless support without accommodation—homeless outreach | USA |

|

| Gabrielian, S., Bromley, E., Hellemann, G. S., Kern, R. S., Goldenson, N. I., Danley, M. E., & Young, A. S. (2015). Factors affecting exits from homelessness among persons with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(4), e469–e476. [31] | 36 | 52.6 | 100.0% | Vets MH/SUD | Homeless service with accommodation—Residential rehabilitation program for homeless adults | USA |

|

| Gabrielian, S., Bromley, E., Hamilton, A. B., Vu, V. T., Alexandrino, A., Jr., Koosis, E., & Young, A. S. (2019). Problem solving skills and deficits among homeless veterans with serious mental illness.. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. Vol.89(2), 2019, pp. 287–295. [33] | 40 | 52.3 | 87.5% | co-/multi-morbidity | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—Housing support (VA) | USA |

|

| Gargaro, J., Gerber, G. J., & Nir, P. (2016). Brain Injury in Persons With Serious Mental Illness Who Have a History of Chronic Homelessness: Could This Impact How Services Are Delivered? Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 35(2), 69–77. [14] | 48 | 43.4 | 69.0% | MH | Health service for homeless people—MH Assertive Community Treatment Team servicing people who are homeless | Canada |

|

| Gash, J. (2010). Examining the relationship between spiritual resources, self-efficacy, life attitudes, cognition, and personal characteristics of homeless African American women Wayne State University]. ccm. [73] | 159 | 45.18 | 0.0% | women only | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Gicas, K. M., Vila-Rodriguez, F., Paquet, K., Barr, A. M., Procyshyn, R. M., Lang, D. J., … Thornton, A. E. (2014). Neurocognitive profiles of marginally housed persons with comorbid substance dependence, viral infection, and psychiatric illness. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 36(10), 1009–1022. [104] | 249 | 43.5% | ? | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—Hotel Study (observational study of people homeless and marginally housed) | Canada |

|

| Gicas, K. M., Jones, A. A., Panenka, W. J., Giesbrecht, C., Lang, D. J., Vila-Rodriguez, F., … Honer, W. G. (2019). Cognitive profiles and associated structural brain networks in a multimorbid sample of marginalized adults. PLoS ONE. Vol.14(6), 2019, ArtID e0218201. [104] | 208 | 42.6% | 82.4% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | Canada |

|

| Gicas, K. M., Thornton, A. E., Waclawik, K., Wang, N., Jones, A. A., Panenka, W. J., … Honer, W. G. (2019). Volumes of the Hippocampal Formation Differentiate Component Processes of Memory in a Community Sample of Homeless and Marginally Housed Persons. Archives of clinical neuropsychology: the official journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 34(4), 548–562. [105] | 227 | 40.9 | 79.0% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—Hotel Study (observational study of people homeless and marginally housed) | Canada |

|

| Gilchrist, G., & Morrison, D. S. (2005). Prevalence of alcohol related brain damage among homeless hostel dwellers in Glasgow. European Journal of Public Health, 15(6), 587–588. [10] | 266 | 53 | 89.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | UK (Scotland) |

|

| Gonzalez, E. A., Dieter, J. N., Natale, R. A., & Tanner, S. L. (2001). Neuropsychological evaluation of higher functioning homeless persons: a comparison of an abbreviated test battery to the mini-mental state exam. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 189(3), 176–181. [54] | 60 | 39.8 | 60.0% | adults | Health service for homeless people—medical service for homeless people | USA |

|

| Gouveia, L., Massanganhe, H., Mandlate, F., Mabunda, D., Fumo, W., Mocumbi, A. O., & de Jesus Mari, J. (2017). Family reintegration of homeless in Maputo and Matola: a descriptive study. Int J Ment Health Syst, 11, 25. [106] | 71 | 37.83 | 93.0% | MH | Mental Health/SUD Treatment Service—psychiatric hospital | Mozambique |

|

| Heckert, U., Andrade, L., Alves, M. J. M. & Martins, C. (1999). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in a southeast city in Brazil. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 249: 150–155. [107] | 83 | 44 | 85.5% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | Brazil |

|

| Hegerty, S. M. (2010). The neuropsychological functioning of men residing in a homeless shelter. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol.70(8-B), 2010, 5197. [15] | 51 | 45 | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Henwood, B. F., Lahey, J., Rhoades, H., Pitts, D. B., Pynoos, J., & Brown, R. T. (2019). Geriatric Conditions Among Formerly Homeless Older Adults Living in Permanent Supportive Housing. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(6), 802–803. [79] | 237 | 41 | 87.0% | older people | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—permanent supportive housing agencies | USA |

|

| Hurstak, E., Johnson, J. K., Tieu, L., Guzman, D., Ponath, C., Lee, C. T., … Kushel, M. (2017). Factors associated with cognitive impairment in a cohort of older homeless adults: Results from the HOPE HOME study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 562–570. [108] | 350 | 58.8 | 76.7% | older people | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | USA |

|

| Hux, K., Schneider, T., & Bennett, K. (2009). Screening for traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 23(1), 8–14. [109] | 240 | 39.93 | 14.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Hwang, S. W., Colantonio, A., Chiu, S., Tolomiczenko, G., Kiss, A., Cowan, L., … Levinson, W. (2008). The effect of traumatic brain injury on the health of homeless people. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 179(8), 779–784. [16] | 904 | 71.7 | 66.5% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| Joyce, D. P., & Limbos, M. (2009). Identification of cognitive impairment and mental illness in elderly homeless men: Before and after access to primary health care. Canadian Family Physician, 55(11), 1110–1111.e1116. [110] | 29 | 51.8 | 100.0% | older people | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| Keigher, S. M., & Greenblatt, S. (1992). Housing emergencies and the etiology of homelessness among the urban elderly. Gerontologist, 32(4), 457–465. [111] | 115 | 21.5 | 57.63% | older people | General, mixed homelessness— | USA |

|

| Keyser, D. R., Mathiesen, S. G. (2010). Co-occurring Disorders and Learning Difficulties: Client Perspectives From Two Community-Based Programs. Psychiatric Services, 61(8), 841–844. [112] | 37 | 41.2 | 52.5% | MH | Mental Health/SUD Treatment Service—mental health community services recovery centre/clubhouse | USA |

|

| Lafferty, B. (2014). Suicide risk in homeless veterans with traumatic brain injury University of Pennsylvania]. ccm. [17] | 122 | 43 | Not stated | vets | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—National Center for Homelessness Among Veterans & 3x VAs | USA |

|

| Llerena, K., Gabrielian, S., & Green, M. F. (2018). Clinical and cognitive correlates of unsheltered status in homeless persons with psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Research, 197, 421–427. [113] | 76 | not stated | 94.7% | MH | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—supported housing waitlist | USA |

|

| Lo, P. C. (2001). Cognitive functioning in a homeless population: The relationship of multiple traumatic brain injuries to neuropsychological test scores. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol.62(3-B), 2001, 1586. [18] | 128 | 52.3 | 64.1% | MH | Other health service—neuropsychology clinic | USA |

|

| Lovisi, G. M., Mann, A. H., Coutinho, E., & Morgado, A. F. (2003). Mental illness in an adult sample admitted to public hostels in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area, Brazil. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38(9), 493–498. [114] | 319 | NA | 75.8% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | Brazil |

|

| Mackelprang, J. L., Harpin, S. B., Grubenhoff, J. A., & Rivara, F. P. (2014). Adverse Outcomes Among Homeless Adolescents and Young Adults Who Report a History of Traumatic Brain Injury. American Journal of Public Health, 104(10), 1986–1992. [115] | 2732 | 56 | 36.7% | young people | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | USA |

|

| Mahmood, Z., Vella, L., Maye, J. E., Keller, A. V., Van Patten, R., Clark, J. M. R., & Twamley, E. W. (2021). Rates of Cognitive and Functional Impairments Among Sheltered Adults Experiencing Homelessness. Psychiatric Services, appips202000065. [49] | 100 | 58 | 81.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Manthorpe, J., Samsi, K., Joly, L., Crane, M., Gage, H., Bowling, A., & Nilforooshan, R. (2019). Service provision for older homeless people with memory problems: a mixed-methods study. NIHR Journals Library. Health Services and Delivery Research, 2, 2. [42] | 42 | 42.6 | 87.1% | Older people | Homeless service with accommodation | UK |

|

| Medalia, A., Herlands, T., & Baginsky, C. (2003). Rehab Rounds: Cognitive Remediation in the Supportive Housing Setting. Psychiatric Services, 54(9), 1219–1220. [116] | 12 | 48 | not stated | adults | General, mixed homelessness—learning centre/supportive housing facility for people who are homeless and have mental illness | USA |

|

| Medalia, A., Saperstein, A. M., Huang, Y., Lee, S., & Ronan, E. J. (2017). Cognitive Skills Training for Homeless Transition-Age Youth: Feasibility and Pilot Efficacy of a Community Based Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 205(11), 859–866. [117] | 91 | not stated | 46.5% | young people | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—youth | USA |

|

| Mejia-Lancheros, C., Lachaud, J., Stergiopoulos, V., Matheson, F. I., Nisenbaum, R., O’Campo, P., & Hwang, S. W. (2020). Effect of Housing First on violence-related traumatic brain injury in adults with experiences of homelessness and mental illness: findings from the at Home/Chez Soi randomised trial, Toronto site. BMJ Open, 10(12), Article e038443. [118] | 381 | 43 | 68.0% | MH | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—housing first support program | Canada |

|

| Monn, A. R. (2016). Intergenerational processess in homeless families linking parent executive function, parenting quality, and child executive function. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol.77(6-B(E)), 2016. [119] | 105 | 48.76 | 5.5% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Munoz, M., Vazquez, C., Koegel, P., Sanz, J., & Burnam, M. A. (1998). Differential patterns of mental disorders among the homeless in Madrid (Spain) and Los Angeles (USA). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 33(10), 514–520. [120] | 1825 | 30.6 | 80.0% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | Spain/USA |

|

| Nikoo, N., Motamed, M., Nikoo, M. A., Strehlau, V., Neilson, E., Saddicha, S. & Krausz, M. (2011). Chronic Physical Health Conditions among Homeless. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 8(1), 81–97. [121] | 500 | not stated | 59.8% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| Nikoo, M., Gadermann, A., To, M. J., Krausz, M., Hwang, S. W., & Palepu, A. (2017). Incidence and Associated Risk Factors of Traumatic Brain Injury in a Cohort of Homeless and Vulnerably Housed Adults in 3 Canadian Cities. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 32(4), E19–E26. [122] | 825 | 42 | 67.6% | adults | General, mixed or General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support (HHiT study—homeless and vulnerably housed (recently homeless) people) | Canada |

|

| Nishio, A., Yamamoto, M., Horita, R., Sado, T., Ueki, H., Watanabe, T., … Shioiri, T. (2015). Prevalence of mental illness, cognitive disability, and their overlap among the homeless in Nagoya, Japan. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 10(9), Article 0138052. [123] | 114 | 42 | 93.0% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | Japan |

|

| Nishio, A., Horita, R., Sado, T., Mizutani, S., Watanabe, T., Uehara, R., & Yamamoto, M. (2017). Causes of homelessness prevalence: Relationship between homelessness and disability. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 71(3), 180–188. [124] | 114 | 37.9 | 93.0% | adults | Other—social welfare agency | Japan |

|

| Oakes, P. D. & R. C. (2008). Intellectual disability in homeless adults: A prevalence study. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 12(4), 325–334. [125] | 50 | 28.77 | 66.0% | adults | Other health service—PCT-run general practice | UK |

|

| Oddy, M., Moir, J. F., Fortescue, D., & Chadwick, S. (2012). The prevalence of traumatic brain injury in the homeless community in a UK city [Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Brain Injury, 26(9), 1058–1064. [126] | 100 | not stated | 75.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | UK |

|

| Okamura, T., Awata, S., Ito, K., Takiwaki, K., Matoba, Y., Niikawa, H., … Takeshima, T. (2017). Elderly men in Tokyo homeless shelters who are suspected of having cognitive impairment. Psychogeriatrics: The Official Journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, 17(3), 206–207. [127] | 51 | 45.3 | 100.0% | older people | Homeless service with accommodation | Japan |

|

| Palladino, B., Montgomery, A. E., Sommers, M., & Fargo, J. D. (2017). Risk of Suicide Among Veterans with Traumatic Brain Injury Experiencing Homelessness. Journal of Military & Veterans’ Health, 25(1), 34–38. [128] | 103 | 42.2 | 100.0% | vets | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—Homeless Support (VA) | USA |

|

| Pluck, G., Kwang-Hyuk, L., David, R., Macleod, D. C., Spence, S. A., & Parks, R. W. (2011). Neurobehavioural and cognitive function is linked to childhood trauma in homeless adults. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466510X490253 [27] | 55 | 52.6 | 80.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | UK |

|

| Pluck, G., Lee, K. H., David, R., Spence, S. A., & Parks, R. W. (2012). Neuropsychological and Cognitive Performance of Homeless Adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science-Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 44(1), 9–15. [129] | 80 | 52.3 | 83.8% | MH | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | UK |

|

| Pluck, G., Nakakarumai, M., & Sato, Y. (2015). Homelessness and cognitive impairment: An exploratory study in Tokyo, Japan [Article]. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 25(3), 122–127. [130] | 16 | 43.4 | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation—homeless service (skills development) | Japan |

|

| Pluck, G., Barajas, B. M., Hernandez-Rodriguez, J. L., & Martínez, M. A. (2020). Language ability and adult homelessness. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(3), 332–344. [131] | 17 | 45.18 | 94.1% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—homeless service | Ecuador |

|

| Raphael-Greenfield, E. (2012). Assessing Executive and Community Functioning Among Homeless Persons with Substance Use Disorders Using the Executive Function Performance Test. Occupational Therapy International, 19(3), 135–143. [132] | 60 | 43.5% | 91.5% | SUD | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—housing first support program | USA |

|

| Rogans-Watson, R., Shulman, C., Lewer, D., Armstrong, M., & Hudson, B. (2020). Premature frailty, geriatric conditions and multimorbidity among people experiencing homelessness: a cross-sectional observational study in a London hostel. Housing Care and Support, 23(3–4), 77–91. [133] | 33 | 42.6% | 91.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation—homeless hotel | UK |

|

| Rogoz, A., & Burke, D. (2016). Older people experiencing homelessness show marked impairment on tests of frontal lobe function. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(3), 240–246. [134] | 171 | 40.9 | 84.2% | older people | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | Australia |

|

| Rohde, P., Noell, J., & Ochs, L. (1999). IQ scores among homeless older adolescents: characteristics of intellectual performance and associations with psychosocial functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 22(3), 319–328. [135] | 50 | 53 | 50.0% | young people | Homeless support without accommodation—homeless outreach program | USA |

|

| Roy, S., Svoboda, T., Issacs, B., Budin, R., Sidhu, A., Biss, R. K., … Connelly, J. O. (2020). Examining the Cognitive and Mental Health Related Disability Rates Among the Homeless: Policy Implications of Changing the Definition of Disability in Ontario. Canadian Psychology, 61(2), 118–126. [136] | 1872 | 39.8 | 69.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| Russell, L. M., Devore, M. D., Barnes, S. M., Forster, J. E., Hostetter, T. A., Montgomery, A. E., … Brenner, L. A. (2013). Challenges associated with screening for traumatic brain injury among US veterans seeking homeless services. American Journal of Public Health, 103 Suppl 2, S211–212. [19] | 678 | 37.83 | 94.7% | vets | Other health service—Health service (veterans) | USA |

|

| San Agustin, M., Cohen, P., Rubin, D., Cleary, S. D., Erickson, C. J. & Allen, J. K. (1999). The Montefiore Community Children’s Project: A controlled study of cognitive and emotional problems of homeless mothers and children. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 76(1), 39–50. [137] | 82 | 44 | 0.0% | women only | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Saperstein, A. M., Lee, S., Ronan, E. J., Seeman, R. S., & Medalia, A. (2014). Cognitive deficit and mental health in homeless transition-age youth. Pediatrics, 134(1), e138–145. [34] | 67 | 45 | 51.5% | young people | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—Homeless service (youth) | USA |

|

| Schmitt, T., Thornton, A. E., Rawtaer, I., Barr, A. M., Gicas, K. M., Lang, D. J., … Panenka, W. J. (2017). Traumatic Brain Injury in a Community-Based Cohort of Homeless and Vulnerably Housed Individuals. Journal of Neurotrauma, 34(23), 3301–3310. [138] | 283 | 41 | 77.1% | adults | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—single room occupancy housing | Canada |

|

| Schutt, R. K., Seidman, L. J., Caplan, B., Martsinkiv, A., & Goldfinger, S. M. (2007). The role of neurocognition and social context in predicting community functioning among formerly homeless seriously mentally ill persons. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33(6), 1388–1396. [139] | 112 | 58.8 | 71.2% | MH | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Seidman, L. J., Caplan, B. B., Tolomiczenko, G. S., Turner, W., Penk, W., Schutt, R. K., & Goldfinger, S. M. (1997). Neuropsychological Function in Homeless Mentally Ill Individuals. The Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 185(1), 3–12. [140] | 116 | 39.93 | 72.4% | MH | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Seidman, L. J., Schutt, R. K., Caplan, B., Tolomiczenko, G. S., Turner, W. M., & Goldfinger, S. M. (2003). The Effect of Housing Interventions on Neuropsychological Functioning Among Homeless Persons With Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. Vol.54(6), 2003, 905–908. [38] | 112 | 71.7 | 71.2% | MH | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Soar, K., Papaioannou, G., & Dawkins, L. (2016). Alcohol Gel Ingestion Among Homeless Eastern and Central Europeans in London: Assessing the Effects on Cognitive Functioning and Psychological Health. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(10), 1274–1282. [141] | 45 | 51.8 | 100.0% | CALD/BME | Homeless support without accommodation—homelessness resource centre | UK |

|

| Solliday-McRoy, C. L. (2002). Neuropsychological functioning of homeless men in shelter: An exploratory study. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol.63(4-B), 2002, 2087. [142] | 75 | 21.5 | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Solliday-McRoy, C., Campbell, T. C., Melchert, T. P., Young, T. J., & Cisler, R. A. (2004). Neuropsychological functioning of homeless men. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 192(7), 471–478. [29] | 90 | 41.2 | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Song, M. J., Nikoo, M., Choi, F., Schutz, C. G., Jang, K., & Krausz, R. M. (2018). Childhood Trauma and Lifetime Traumatic Brain Injury Among Individuals Who Are Homeless. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 33(3), 185–190. [20] | 487 | 43 | 57.7% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support (British Columbia Health of the Homeless Survey) | Canada |

|

| Souza, A. M., Tsai, J. H. C., Pike, K. C., Martin, F., & McCurry, S. M. (2020). Cognition, Health, and Social Support of Formerly Homeless Older Adults in Permanent Supportive Housing. Innovation in Aging, 4(1), 1–9. [143] | 53 | not stated | 86.8% | older people | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—permanent supportive housing agencies | USA |

|

| Stergiopoulos, V., Cusi, A., Bekele, T., Skosireva, A., Latimer, E., Schutz, C., … Rourke, S. B. (2015). Neurocognitive impairment in a large sample of homeless adults with mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 131(4), 256–268. [32] | 1500 | 52.3 | 67.0% | MH | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—housing first support program | Canada |

|

| Synovec, C. E. (2018). Occupational Therapy in Health Care Agencies Serving Adults Experiencing Homelessness: Outcomes of a Pilot Model. Occupational Therapy in Health Care Agencies Serving Adults Experiencing Homelessness: Outcomes of a Pilot Model, 1–1. [144] | 172 | NA | 73.0% | adults | Health service for homeless people | USA |

|

| Synovec, C. E. (2020). Evaluating Cognitive Impairment and Its Relation to Function in a Population of Individuals Who Are Homeless. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 36(4), 330–352. [11] | 172 | 56 | 73.0% | adults | Health service for homeless people | USA |

|

| Synovec, C. E., & Berry, S. (2020). Addressing brain injury in health care for the homeless settings: A pilot model for provider training. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation. Vol.65(2), 2020, pp. 285–296. [21] | 172 | 58 | 73.0% | adults | Health service for homeless people | USA |

|

| Teesson, M., & Buhrich, N. (1993). Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment Among Homeless Men in a Shelter in Australia. Psychiatric Services, 44(12), 1187–1189. [145] | 56 | 42.6 | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | Australia |

|

| Thompson, A., Richardson, P., Pirmohamed, M., & Owens, L. (2020). Alcohol-related brain injury: An unrecognized problem in acute medicine. Alcohol, 88, 49–53. [146] | 1276 | 48 | 69.4% | SUD | Other health service—hospital | UK |

|

| To, M. J., O’Brien, K., Palepu, A., Hubley, A. M., Farrell, S., Aubry, T., … Hwang, S. W. (2015). Healthcare Utilization, Legal Incidents, and Victimization Following Traumatic Brain Injury in Homeless and Vulnerably Housed Individuals: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 30(4), 270–276. [22] | 1181 | not stated | 66.2% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| Topolovec-Vranic, J., Ennis, N., Howatt, M., Ouchterlony, D., Michalak, A., Masanic, C., … Cusimano, M. D. (2014). Traumatic brain injury among men in an urban homeless shelter: observational study of rates and mechanisms of injury. CMAJ open, 2(2), E69–76. [147] | 111 | 43 | 100.0% | men only | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| Topolovec-Vranic, J., Schuler, A., Gozdzik, A., Somers, J., Bourque, P. E., Frankish, C. J., … Hwang, S. W. (2017). The high burden of traumatic brain injury and comorbidities amongst homeless adults with mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 87, 53–60. [23] | 2088 | 48.76 | 67.6% | MH | Housing support program to people at risk/formerly homeless—Homelessness program (At Home/Chez Soi) | Canada |

|

| Twamley, E. W., Hays, C. C., Van Patten, R., Seewald, P. M., Orff, H. J., Depp, C. A., … Jak, A. J. (2019). Neurocognition, psychiatric symptoms, and lifetime homelessness among veterans with a history of traumatic brain injury. Psychiatry Research, 271, 167–170. [148] | 32 | 30.6 | 100.0% | vets | Other health service—medical records from veterans referred for neuropsych testing following TBI | USA |

|

| Valera, E. M., & Berenbaum, H. (2003). Brain injury in battered women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Vol.71(4), 2003, 797–804. [24] | 99 | not stated | 0.0% | women only | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—programs targeting women leaving or experiencing violence | USA |

|

| Van Straaten, B., Rodenburg, G., Van der Laan, J., Boersma, S. N., Wolf, J. R., & Van de Mheen, D. (2017). Self-reported care needs of Dutch homeless people with and without a suspected intellectual disability: a 1.5-year follow-up study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(1), 123–136. [40] | 336 | 42 | 84.6% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support | Netherlands |

|

| Vella, L. (2015). Cognitive assessment of the sheltered homeless. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol.75(12-B(E)), 2015. [41] | 100 | 42 | 81.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation | USA |

|

| Vila-Rodriguez, F., Panenka, W. J., Lang, D. J., Thornton, A. E., Vertinsky, T., Wong, H., … Honer, W. G. (2013). The hotel study: Multimorbidity in a community sample living in marginal housing. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(12), 1413–1422. [149] | 293 | 37.9 | 76.8% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—Hotel Study (observational study of people homeless and marginally housed) | Canada |

|

| Waclawik, K., Jones, A. A., Barbic, S. P., Gicas, K. M., O’Connor, T. A., Smith, G. N., … Thornton, A. E. (2019). Cognitive Impairment in Marginally Housed Youth: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 270. [150] | 101 | 28.77 | 75.0% | young people | Homeless service with accommodation | Canada |

|

| White, P., Townsend, C., Lakhani, A., Cullen, J., Bishara, J., & White, A. (2019). The Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment among People Attending a Homeless Service in Far North Queensland with a Majority Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander People. Australian Psychologist, 54(3), 193–201. [36] | 60 | not stated | 67.0% | indigenous | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—homeless service (veterans) | Australia |

|

| Yim, L. C., Leung, H. C., Chan, W. C., Lam, M. H., & Lim, V. W. (2015). Prevalence of Mental Illness among Homeless People in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 10(10), e0140940. [151] | 79 | 45.3 | 93.7% | adults | General, mixed or unspecified homelessness support—NGO Homelessness services | Hong Kong |

|

| Zhou, L. W., Panenka, W. J., Jones, A. A., Gicas, K. M., Thornton, A. E., Heran, M. K. S., … Field, T. S. (2019). Prevalence and Risk Factors of Brain Infarcts and Associations With Cognitive Performance in Tenants of Marginal Housing. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8(13), 1–11. [152] | 228 | 42.2 | 77.0% | adults | Homeless service with accommodation (Crisis/shelter)—Homelessness service (SRO Hotels) | Canada |

|

| Zlotnick, C., Fischer, P. J., & Agnew, J. (1995). Perceptuomotor function of homeless males in alcohol rehabilitation. Journal of Substance Abuse, 7(2), 235–244. [153] | 76 | 52.6 | 100.0% | SUD | Mental Health/SUD Treatment Service—Health service (A & D/Psych) | USA |

|

Appendix C

| Individual Instruments (Including Each Version) | Times Described |

|---|---|

| Cognitive Screens | |

| Action Fluency (verbs) | 1 |

| Adaptive Behaviour Assessment Scale (ABAS) | 1 |

| Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE) | 1 |

| Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III) | 1 |

| Adult memory and Information Processing battery (Information Processing Task B) | 1 |

| Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) | 2 |

| Allen Cognitive Level Screen-2000 (ACLS) | 1 |

| Allen Cognitive Level Screen (ACLS-5) | 3 |

| Aphasia Screening test (AST) | 1 |

| Bender Visual Motor Gestalt Test | 1 |

| Benton Line Orientation | 2 |

| Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT) administration A | 1 |

| Boston Naming Test (BNT) | 2 |

| The Burglar’s Story | 2 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) long delay free recall | 1 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) trials 1–5 | 2 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) | 1 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT-II) trials 1–5 | 1 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT-II) immediate free recall | 2 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT-II) long delay free recall | 3 |

| Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) Intra-Dimensional Extra-Dimensional subtest | 7 |

| Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) A-prime score from the Rapid Visual Information Processing subtest | 7 |

| Category Fluency (animals) | 2 |

| Clock Drawing test | 1 |

| Cognitive Stability Index | 1 |

| Colour Trails Test | 1 |

| Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; version 1.1) | 1 |

| Cookie Card Theft Test (CCTT) | 1 |

| Connors’ Continuous Performance Test (CPT-II) | 2 |

| Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) (FAS) | 6 |

| auditory Continuous Performance Test (CPT) | 4 |

| Dean–Woodcock Sensory Motor Battery (D-WSMB) Motor Functioning (Gait and Station, Romberg, Finger Tapping, Grip Strength) | 1 |

| Dean–Woodcock Sensory Motor Battery (D-WSMB) Sensory Functioning (Object Identification, Finger Identification) | 1 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Colour Word Inhibition Test | 2 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Verbal Fluency | 1 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Tower | 1 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Trail Making | 4 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Trail Making motor speed (test #5) | 1 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Trail Making Number-Letter Switching | 4 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Verbal Fluency-Category Fluency | 2 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Verbal Fluency-Category Switching | 2 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Verbal Fluency-Letter Fluency | 4 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Trail Making Visual Scanning | 3 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Trail Making Number Sequencing | 3 |

| Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Trail Making Letter Sequencing | 3 |

| Executive Function Performance Test (EFPT) | 3 |

| Finger Tapping Test | 3 |

| Frontal Systems Behaviour Scale (FrSBe) | 2 |

| Go-NoGo | 1 |

| Grooved Pegboard Test | 2 |

| Hayes Ability Screening Index (HASI) | 1 |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-R (HVLT-R) | 12 |

| Iowa Gambling Test | 8 |

| Japanese Adult Reading Test | 1 |

| Kimberley Indigenous Cognitive Assessment | 1 |

| Learning Needs Screening Tool (LNST) | 1 |

| Letter-Number Span (LNS) | 1 |

| Line Tracing Test | 1 |

| The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) | 1 |

| Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | 1 |

| Mini-Cog | 1 |

| Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) | 20 |

| Minnesota Executive Function Scale (MEFS; Carlson & Zelatzp, 2014) | 1 |

| Modified Mini Mental State (3MS) Examination | 2 |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | 7 |

| Motor Sequencing (non-preferred hand)—Luria Manual Hand Positions Test | 2 |

| Motor Sequencing (preferred hand)—Luria Manual Hand Positions Test | 2 |

| Multiple-Problem Screening Inventory (MPSI) subscales (of consideration—(l) confused thinking, (n) memory loss) | 1 |

| NART/NART-R | 2 |

| Neurobehavioural cognitive Status Examination (Cognistat) | 2 |

| Neuropsychological Assessment Questionnaire | 1 |

| NIH Toolbox Picture Vocabulary (PVT) | 1 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Revised (PVT-R) | 1 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th Ed (PVT-IV) | 1 |

| Patient Reported Outcomes Measure Information System (PROMIS) measure: Cognition | 1 |

| Porteus Maze Test | 4 |

| Purdue Pegboard | 1 |

| Prospective and Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ) | 1 |

| Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices | 3 |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) | 2 |

| Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT) copy trial | 2 |

| Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT) immediate recall | 1 |

| Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT) delayed recall | 2 |

| Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Design | 1 |

| Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT) | 3 |

| Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) | 2 |

| Rowland universal dementia assessment scale (RUDAS) | 1 |

| Ruff Figural Fluency Test | 1 |

| Self-Report of cognitive function and memory—interview only, no formal tool | 2 |

| Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) | 1 |

| Simple Visual Reaction Time (SVRT) | 1 |

| Six-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT) | 1 |

| Stroop Colour Word Test | 10 |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) | 2 |

| Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA) | 1 |

| Tinkertoy Test | 1 |

| Tower of Hanoi | 1 |

| Tower of London task (TOL) | 1 |

| Trail Making Test-Part A | 8 |

| Trail Making Test-Part B | 11 |

| University of California, San Diego, Performance-Based Skills Assessment–Brief (UPSA-B) | 1 |

| Visual Verbal Total Misses | 2 |

| Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) | 6 |

| Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) Matrix Reasoning subtest | 1 |

| Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) Vocabulary subtest | 3 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Ed (WAIS-III) | 1 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Ed (WAIS-III) Arithmetic | 1 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Ed (WAIS-III) Block design | 1 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Ed (WAIS-III) Digit Span | 7 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Ed (WAIS-III) Digit Symbol-Coding | 4 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Ed (WAIS-III) Letter-Number Sequencing | 1 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Ed (WAIS-III) Matrix Reasoning | 1 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rdEd (WAIS-III) Symbol Search | 2 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rdEd (WAIS-III) Digit Symbol | 1 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rdEd (WAIS-III) Picture completion | 2 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rdEd (WAIS-III) Information | 2 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 4thEd (WAIS-IV) | 1 |

| WAIS-IV Digit Span | 2 |

| WAIS-IV Coding | 3 |

| WAIS-IV Symbol Search | 1 |

| WAIS-IV Arithmetic | 1 |

| WAIS-R Digit Span | 3 |

| WAIS-R Block design | 3 |

| WAIS-R Digit Symbol | 5 |

| WAIS-R Vocabulary | 3 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale -Revised (WAIS-R) | 3 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised Spatial Span Subtest as a neurological instrument (WAIS-RNI) | 1 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale 3rdEd (WMS-III) | 1 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale 4thEd (WMS-IV) | 2 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale 4thEd (WMS-IV) Logical Memory I | 2 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale 4thEd (WMS-IV) Logical Memory II | 2 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised (WMS-R) Logical Memory Immediate Recall | 2 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised (WMS-R) Logical Memory Delayed Recall | 5 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised (WMS-R) Verbal Memory | 3 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised (WMS-R) Visual Memory | 1 |

| Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) | 10 |

| WHODAS | 1 |

| Wide Range Achievement Test 4thEd (WRAT-R)—Spelling | 1 |

| Wide Range Achievement Test 4thEd (WRAT-R)—Reading | 1 |

| Wide Range Achievement Test 4thEd (WRAT-R)—Arithmetic | 1 |

| Wide Range Achievement Test 4thEd (WRAT-IV) | 5 |

| Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning—2nd Ed (WRAML2) Verbal Memory | 1 |

| Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning—2nd Ed (WRAML2) Visual Memory | 1 |

| Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning—2nd Ed (WRAML2) Screening Memory | 1 |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) | 8 |

| Woodcock Johnson Psychoeducational Battery-Revised: Tests of Achievement (WJ-R ACH) (Letter-Word Identification and Passage Comprehension Subtests) | 2 |

| Word Accentuation Test (Spanish) | 1 |

| National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC)—Health Chapter (Self Report) | 1 |

| CASE MANAGER ASSESSMENT: Rapid Assessment of Residential Support (RARS) | 1 |

| CASE MANAGER ASSESSMENT: Interview with case manager/key worker/support staff re whether they believe the person has memory problems/can live independently | 2 |

| Combination: Identified High Risk for ARBI (through YES to either 3x hosp in 12 months; 2x hosp in 30 days; family concern re cognition) Plus MoCA < 23 | 1 |

| Brain Injury Screens | |

| Brain Injury Screening Index (BISI) | 2 |

| Brain Injury Screening Questionnaire (BISQ) | 2 |

| HELPS | 2 |

| OSU TBI-ID | 10 |

| TBI-4 | 3 |

| Single or series of questions, e.g., “Have you ever had a blow to the head?” | 14 |

| National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC)—Health Chapter (Self-report Head injury with Knock out, dizziness, confusion, or disorientation) | 1 |

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 58th Session of the Commission for Social Development; Conference Room 4; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, B.; Dowling, S.; Cameron, A. Cognitive impairment and homelessness: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, e125–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burra, T.A.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Rourke, S.B. A systematic review of cognitive deficits in homeless adults: Implications for service delivery. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, N.; Roy, S.; Topolovec-Vranic, J. Memory impairment among people who are homeless: A systematic review. Memory 2015, 23, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depp, C.A.; Vella, L.; Orff, H.J.; Twamley, E.W. A quantitative review of cognitive functioning in homeless adults. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backer, T.E.; Howard, E.A. Cognitive impairments and the prevention of homelessness: Research and practice review. J. Prim. Prev. 2007, 28, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, J.; Kot, N.; Ennis, N.; Colantonio, A.; Ouchterlony, D.; Cusimano, M.D.; Topolovec-Vranic, J. Traumatic brain injury and cognitive impairment in men who are homeless. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 2210–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, R.W.; Stevens, R.J.; Spence, S.A. A systematic review of cognition in homeless children and adolescents. J. R. Soc. Med. 2007, 100, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, C.; Yamamoto, A.; Richardson, C.G.; Zivanovic, R.; Lin, D.; Mathias, S. Examining patterns of cognitive impairment among homeless and precariously housed urban youth. J. Adolesc. 2019, 72, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, G.; Morrison, D.S. Prevalence of alcohol related brain damage among homeless hostel dwellers in Glasgow. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 15, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synovec, C.E. Evaluating Cognitive Impairment and Its Relation to Function in a Population of Individuals Who Are Homeless. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2020, 36, 330–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.M.; Russell, L.M.; Hostetter, T.A.; Forster, J.E.; Devore, M.D.; Brenner, L.A. Characteristics of Traumatic Brain Injuries Sustained Among Veterans Seeking Homeless Services. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2015, 26, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bymaster, A.; Chung, J.; Banke, A.; Choi, H.J.; Laird, C. A Pediatric Profile of a Homeless Patient in San Jose, California. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2017, 28, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargaro, J.; Gerber, G.J.; Nir, P. Brain Injury in Persons With Serious Mental Illness Who Have a History of Chronic Homelessness: Could This Impact How Services Are Delivered? Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2016, 35, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerty, S.M. The Neuropsychological Functioning of Men Residing in a Homeless Shelter; Marquette University: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.W.; Colantonio, A.; Chiu, S.; Tolomiczenko, G.; Kiss, A.; Cowan, L.; Redelmeier, D.A.; Levinson, W. The effect of traumatic brain injury on the health of homeless people. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 179, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, B. Suicide Risk in Homeless Veterans with Traumatic Brain Injury; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, P.C. Cognitive Functioning in a Homeless Population: The Relationship of Multiple Traumatic Brain Injuries to Neuropsychological Test Scores; Fuller Theological Seminary–School of Psychololgy: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pluck, G.; Kwang-Hyuk, L.; David, R.; Macleod, D.C.; Spence, S.A.; Parks, R.W. Neurobehavioural and cognitive function is linked to childhood trauma in homeless adults. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 50, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.M.; Devore, M.D.; Barnes, S.M.; Forster, J.E.; Hostetter, T.A.; Montgomery, A.E.; Casey, R.; Kane, V.; Brenner, L.A. Challenges associated with screening for traumatic brain injury among US veterans seeking homeless services. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, S211–S212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.J.; Nikoo, M.; Choi, F.; Schutz, C.G.; Jang, K.; Krausz, R.M. Childhood Trauma and Lifetime Traumatic Brain Injury Among Individuals Who Are Homeless. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018, 33, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synovec, C.E.; Berry, S. Addressing brain injury in health care for the homeless settings: A pilot model for provider training. Work. J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2020, 65, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, M.J.; O’Brien, K.; Palepu, A.; Hubley, A.M.; Farrell, S.; Aubry, T.; Gogosis, E.; Muckle, W.; Hwang, S.W. Healthcare Utilization, Legal Incidents, and Victimization Following Traumatic Brain Injury in Homeless and Vulnerably Housed Individuals: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015, 30, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolovec-Vranic, J.; Schuler, A.; Gozdzik, A.; Somers, J.; Bourque, P.E.; Frankish, C.J.; Jbilou, J.; Pakzad, S.; Palma Lazgare, L.I.; Hwang, S.W. The high burden of traumatic brain injury and comorbidities amongst homeless adults with mental illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 87, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, E.M.; Berenbaum, H. Brain injury in battered women. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, J.L.; Thornton, A.E.; Sevick, J.M.; Silverberg, N.D.; Barr, A.M.; Honer, W.G.; Panenka, W.J. Traumatic brain injury in homeless and marginally housed individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e19–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topolovec-Vranic, J.; Ennis, N.; Colantonio, A.; Cusimano, M.D.; Hwang, S.W.; Kontos, P.; Ouchterlony, D.; Stergiopoulos, V. Traumatic brain injury among people who are homeless: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gicas, K.M.; Jones, A.A.; Panenka, W.J.; Giesbrecht, C.; Lang, D.J.; Vila-Rodriguez, F.; Leonova, O.; Barr, A.M.; Procyshyn, R.M.; Su, W.; et al. Cognitive profiles and associated structural brain networks in a multimorbid sample of marginalized adults. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solliday-McRoy, C.; Campbell, T.C.; Melchert, T.P.; Young, T.J.; Cisler, R.A. Neuropsychological functioning of homeless men. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004, 192, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.; Chrosniak, L.; Wanschura, P.; Flinn, J. Indications of Reduced Prefrontal Cortical Function in Chronically Homeless Adults. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielian, S.; Bromley, E.; Hellemann, G.S.; Kern, R.S.; Goldenson, N.I.; Danley, M.E.; Young, A.S. Factors affecting exits from homelessness among persons with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, e469–e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiopoulos, V.; Cusi, A.; Bekele, T.; Skosireva, A.; Latimer, E.; Schutz, C.; Fernando, I.; Rourke, S.B. Neurocognitive impairment in a large sample of homeless adults with mental illness. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015, 131, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielian, S.; Bromley, E.; Hamilton, A.B.; Vu, V.T.; Alexandrino, A., Jr.; Koosis, E.; Young, A.S. Problem solving skills and deficits among homeless veterans with serious mental illness. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saperstein, A.M.; Lee, S.; Ronan, E.J.; Seeman, R.S.; Medalia, A. Cognitive deficit and mental health in homeless transition-age youth. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e138–e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.H.; Helfrich, C.A.; Coster, W.J.; Rogers, E.S. Factors associated with community participation among individuals who have experienced homelessness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 11364–11378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.; Townsend, C.; Lakhani, A.; Cullen, J.; Bishara, J.; White, A. The Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment among People Attending a Homeless Service in Far North Queensland with a Majority Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander People. Aust. Psychol. 2019, 54, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, T.P.; Johnson, E.E.; Redihan, S.; Borgia, M.; Rose, J. Needing Primary Care But Not Getting It: The Role of Trust, Stigma and Organizational Obstacles reported by Homeless Veterans. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2015, 26, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, L.J.; Schutt, R.K.; Caplan, B.; Tolomiczenko, G.S.; Turner, W.M.; Goldfinger, S.M. The Effect of Housing Interventions on Neuropsychological Functioning Among Homeless Persons with Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003, 54, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, B.; Schutt, R.K.; Turner, W.M.; Goldfinger, S.M.; Seidman, L.J. Change in neurocognition by housing type and substance abuse among formerly homeless seriously mentally ill persons. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 83, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Straaten, B.; Rodenburg, G.; Van der Laan, J.; Boersma, S.N.; Wolf, J.R.; Van de Mheen, D. Self-reported care needs of Dutch homeless people with and without a suspected intellectual disability: A 1.5-year follow-up study. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, L. Cognitive Assessment of the Sheltered Homeless; San Diego State University: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Manthorpe, J.; Samsi, K.; Joly, L.; Crane, M.; Gage, H.; Bowling, A.; Nilforooshan, R. Service provision for older homeless people with memory problems: A mixed-methods study. NIHR J. Library. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2019, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Garcia, I. Why Do Homeless Families Exit and Return the Homeless Shelter? Factors Affecting the Risk of Family Homelessness in Salt Lake County (Utah, United States) as a Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, A.T.; Rothwell, D.W. What leads to homeless shelter re-entry? An exploration of the psychosocial, health, contextual and demographic factors. Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e94–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Specialist Homelessness Services Annual Report 2020–21; Australian Government, AIHW: Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia, 2021.

- Kushel, M.B.; Perry, S.; Bangsberg, D.; Clark, R.; Moss, A.R. Emergency Department Use Among the Homeless and Marginally Housed: Results From a Community-Based Study. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Government. Pathways to Homelessness: Final Report—December 2021; Department of Communities and Justice, NSW Government: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2021.

- Tierney, M.C.; Charles, J.; Jaglal, S.; Snow, W.G.; Szalai, J.P.; Spizzirri, F.; Fisher, R.H. Identification of Those at Greatest Risk of Harm Among Cognitively Impaired People Who Live Alone. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2001, 8, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Z.; Vella, L.; Maye, J.E.; Keller, A.V.; Van Patten, R.; Clark, J.M.R.; Twamley, E.W. Rates of Cognitive and Functional Impairments Among Sheltered Adults Experiencing Homelessness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adshead, C.D.; Norman, A.; Holloway, M. The inter-relationship between acquired brain injury, substance use and homelessness; the impact of adverse childhood experiences: An interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 3411–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocht, C.; Sheldon, P.; Synovec, C. A clinical description of strategies to address traumatic brain injury experienced by homeless patients at Baltimore’s medical respite program. Work. J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2020, 65, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dams-O’Connor, K.; Cantor, J.B.; Brown, M.; Dijkers, M.P.; Spielman, L.A.; Gordon, W.A. Screening for Traumatic Brain Injury: Findings and Public Health Implications. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014, 29, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.J.; Grimmer, K.; Bradley, A.; Direen, T.; Baker, N.; Marin, T.; Kelly, M.T.; Gardner, S.; Steffens, M.; Burgess, T.; et al. Health assessments and screening tools for adults experiencing homelessness: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E.A.; Dieter, J.N.; Natale, R.A.; Tanner, S.L. Neuropsychological evaluation of higher functioning homeless persons: A comparison of an abbreviated test battery to the mini-mental state exam. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001, 189, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.M. Neuropsychological Functioning and Attrition Rates in Outpatient Substance Dependence Treatment; Marquette University: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mackelprang, J.; Hartanto, S.; Thielking, M. Traumatic Brain Injury and Homelessness; Swinburne University of Technology: Hawthorn, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Homelessness Assistance Programs. 2022. Available online: https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Department for Communities and Local Government. Addressing Complex Needs: Improving Services for Vulnerable Homeless People; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2015.

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. Report on Government Services 2021: PART G, SECTION 19: Homelessness Services; Australian Government Productivity Commission: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021.

- Government of Canada. Canada’s National Housing Strategy—A Place to Call Home; Government of Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019.

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: North Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; The Joanna Briggs Institute: North Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Assessments, P. Pearson Assessments. 2022. Available online: https://www.pearsonassessments.com/professional-assessments.html (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Psychological Assessment Resources Inc. 2022. Available online: https://www.parinc.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an Indicator of Organic Brain Damage. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Screening for TBI Using the OSU TBI-ID Method. 2022. Available online: https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/neurological-institute/neuroscience-research-institute/research-centers/ohio-valley-center-for-brain-injury-prevention-and-rehabilitation/for-professionals/screening-for-tbi (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Brenner, L.A.; Homaifar, B.Y.; Olson-Madden, J.H.; Nagamoto, H.T.; Huggins, J.; Schneider, A.L.; Forster, J.E.; Matarazzo, B.; Corrigan, J.D. Prevalence and screening of traumatic brain injury among veterans seeking mental health services. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2013, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, J. Examining the relationship between spiritual resources, self-efficacy, life attitudes, cognition, and personal characteristics of homeless African American women. In Nursing; Wayne State University: Detroit, MI, USA, 2010; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, J.D.; Bogner, J. Initial Reliability and Validity of the Ohio State University TBI Identification Method. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007, 22, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, N.; Gorgens, K.; Lehto, M.; Meyer, L.; Dettmer, J.; Gafford, J. Sensitivity and Specificity of the Ohio State University Traumatic Brain Injury Identification Method to Neuropsychological Impairment. Crim. Justice Behav. 2018, 45, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo-Rodriguez, I.; Smailagic, N.; i Figuls, M.R.; Ciapponi, A.; Sanchez-Perez, E.; Giannakou, A.; Pedraza, O.L.; Bonfill Cosp, X.; Cullum, S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, D.A. A Quantitative Review of Intellectual Functioning in the Ranges of Intellectual Disability and Borderline Intelligence for Adults Who Are Homeless: Implications for Identification, Service, and Prevention; Wheaton College Graduate School: Wheaton, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ashendorf, L.; Jefferson, A.; Oconnor, M.; Chaisson, C.; Green, R.; Stern, R. Trail Making Test errors in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2008, 23, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henwood, B.F.; Lahey, J.; Rhoades, H.; Pitts, D.B.; Pynoos, J.; Brown, R.T. Geriatric Conditions Among Formerly Homeless Older Adults Living in Permanent Supportive Housing. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 802–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuthnott, K.; Frank, J. Trail Making Test, Part B as a Measure of Executive Control: Validation Using a Set-Switching Paradigm. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2000, 22, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortte, K.B.; Horner, M.D.; Windham, W.K. The Trail Making Test, Part B: Cognitive Flexibility or Ability to Maintain Set? Appl. Neuropsychol. 2002, 9, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeare, C.; Sabelli, A.; Taylor, B.; Holcomb, M.; Dumitrescu, C.; Kirsch, N.; Erdodi, L. The Importance of Demographically Adjusted Cutoffs: Age and Education Bias in Raw Score Cutoffs Within the Trail Making Test. Psychol. Inj. Law 2019, 12, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, J.; Cook, D.; Fellows, R.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. An analysis of a digital variant of the Trail Making Test using machine learning techniques. Technol. Health Care 2017, 25, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson-Madden, J.H.; Homaifar, B.Y.; Hostetter, T.A.; Matarazzo, B.B.; Huggins, J.; Forster, J.E.; Schneider, A.L.; Nagamoto, H.T.; Corrigan, J.D.; Brenner, L.A. Validating the traumatic brain injury-4 screening measure for veterans seeking mental health treatment with psychiatric inpatient and outpatient service utilization data. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, L.A.; Hostetter, T.A.; Barnes, S.M.; Stearns-Yoder, K.A.; Soberay, K.A.; Forster, J.E. Traumatic brain injury, psychiatric diagnoses, and suicide risk among Veterans seeking services related to homelessness. Brain Inj. 2017, 31, 1731–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, J.; Corrigan, J.D. Reliability and Predictive Validity of the Ohio State University TBI Identification Method With Prisoners. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009, 24, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.E.; Pantelis, C.; Duke, P.J.; Barnes, T.R. Psychopathology, social and cognitive functioning in a hostel for homeless women. Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 168, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacciardi, S.; Maremmani, A.G.I.; Nikoo, N.; Cambioli, L.; Schütz, C.; Jang, K.; Krausz, M. Is bipolar disorder associated with tramautic brain injury in the homeless? Riv. Psichiatr. 2017, 52, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Barak, Y.; Cohen, A. Characterizing the elderly homeless: A 10-year study in Israel. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2003, 37, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, B.B. Gender Differences in the Rehospitalization of Substance Abusers Among Homeless Military Veterans. J. Drug Issues 2004, 34, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousman, C.A.; Twamley, E.W.; Vella, L.; Gale, M.; Norman, S.B.; Judd, P.; Everall, I.P.; Heaton, R.K. Homelessness and neuropsychological impairment: Preliminary analysis of adults entering outpatient psychiatric treatment. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, A.J.; Duke, P.J.; Nelson, H.E.; Pantelis, C.; Barnes, T.R.E. Cognitive function and duration of rooflessness in entrants to a hostel for homeless men. Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 169, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.T.; Kiely, D.K.; Bharel, M.; Mitchell, S.L. Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.T.; Hemati, K.; Riley, E.D.; Lee, C.T.; Ponath, C.; Tieu, L.; Guzman, D.; Kushel, M.B. Geriatric Conditions in a Population-Based Sample of Older Homeless Adults. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrich, N.; Hodder, T.; Teesson, M. Prevalence of cognitive impairment among homeless people in inner Sydney. Psychiatr. Serv. 2000, 51, 520–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaneda, R.; Lifshutz, H.; Galanter, M.; Franco, H. Age at onset of alcoholism as a predictor of homelessness and drinking severity. J. Addict. Dis. 1993, 12, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotman, A.; Sandman, C. Cognitive deficits and their remediation in the homeless. J. Cogn. Rehabil. 1997, 15, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, D. Prefrontal Cortical Function in the Adult Chronically Homeless. Ph.D. Thesis, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Distefano, R. Autonomy Support in Parents and Young Children Experiencing Homelessness: A Mixed Method Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duerksen, C.L. Differences between Domiciled and Undomiciled Men on Measures of Executive Functioning. Ph.D. Thesis, California School of Professional Psychology, Los Angels, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin, A.; Lunsky, Y.; Nisenbaum, R.; Hwang, S.W.; O’Campo, P.; Stergiopoulos, V. Borderline Intellectual Functioning and Lifetime Duration of Homelessness among Homeless Adults with Mental Illness. Healthcare Policy 2018, 14, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, M.M.; Quadflieg, N. Three year course and outcome of mental illness in homeless men—A prospective longitudinal study based on a representative sample. Eur. Arch. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 2005, 255, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulks, E.F.; McCown, W.G.; Duckworth, M.; Sutker, P.B. Neuropsychological Testing of Homeless Mentally Ill Veterans. Psychiatr. Serv. 1990, 41, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gicas, K.M.; Vila-Rodriguez, F.; Paquet, K.; Barr, A.M.; Procyshyn, R.M.; Lang, D.J.; Smith, G.N.; Baitz, H.A.; Giesbrecht, C.J.; Montaner, J.S.; et al. Neurocognitive profiles of marginally housed persons with comorbid substance dependence, viral infection, and psychiatric illness. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2014, 36, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gicas, K.M.; Thornton, A.E.; Waclawik, K.; Wang, N.; Jones, A.A.; Panenka, W.J.; Lang, D.J.; Smith, G.N.; Vila-Rodriguez, F.; Leonova, O.; et al. Volumes of the Hippocampal Formation Differentiate Component Processes of Memory in a Community Sample of Homeless and Marginally Housed Persons. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. Off. J. Natl. Acad. Neuropsychol. 2019, 34, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, L.; Massanganhe, H.; Mandlate, F.; Mabunda, D.; Fumo, W.; Mocumbi, A.O.; de Jesus Mari, J. Family reintegration of homeless in Maputo and Matola: A descriptive study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2017, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckert, U.; Andrade, L.; Alves, M.J.; Martins, C. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in a southeast city in Brazil. Eur. Arch. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 249, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurstak, E.; Johnson, J.K.; Tieu, L.; Guzman, D.; Ponath, C.; Lee, C.T.; Jamora, C.W.; Kushel, M. Factors associated with cognitive impairment in a cohort of older homeless adults: Results from the HOPE HOME study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 178, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hux, K.; Schneider, T.; Bennett, K. Screening for traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2009, 23, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, D.P.; Limbos, M. Identification of cognitive impairment and mental illness in elderly homeless men: Before and after access to primary health care. Can. Fam. Physician 2009, 55, 1110–1111.e6. [Google Scholar]

- Keigher, S.M.; Greenblatt, S. Housing emergencies and the etiology of homelessness among the urban elderly. Gerontologist 1992, 32, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, D.R.; Mathiesen, S.G. Co-occurring Disorders and Learning Difficulties: Client Perspectives From Two Community-Based Programs. Psychiatr. Serv. 2010, 61, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena, K.; Gabrielian, S.; Green, M.F. Clinical and cognitive correlates of unsheltered status in homeless persons with psychotic disorders. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 197, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovisi, G.M.; Mann, A.H.; Coutinho, E.; Morgado, A.F. Mental illness in an adult sample admitted to public hostels in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area, Brazil. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003, 38, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]