Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Caregivers of People with an Intellectual Disability, in Comparison to Carers of Those with Other Disabilities and with Mental Health Issues: A Multicountry Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

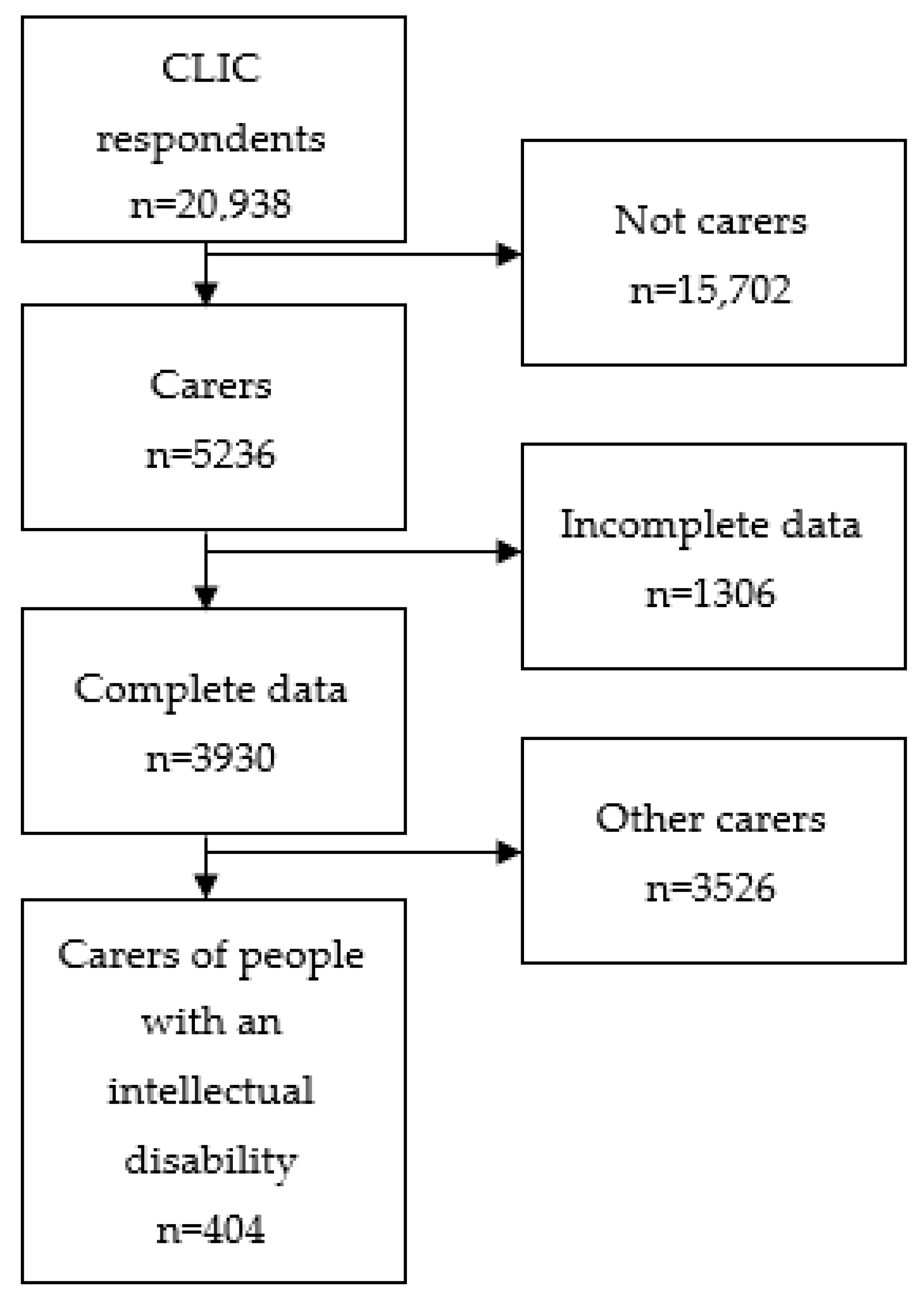

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Research Tools

2.3.1. Sociodemographic

2.3.2. Loneliness

2.3.3. Caregiver/Carer Burden

2.3.4. Isolation

2.3.5. Changes during COVID-19

2.4. Ethical Approval

2.5. Analysis

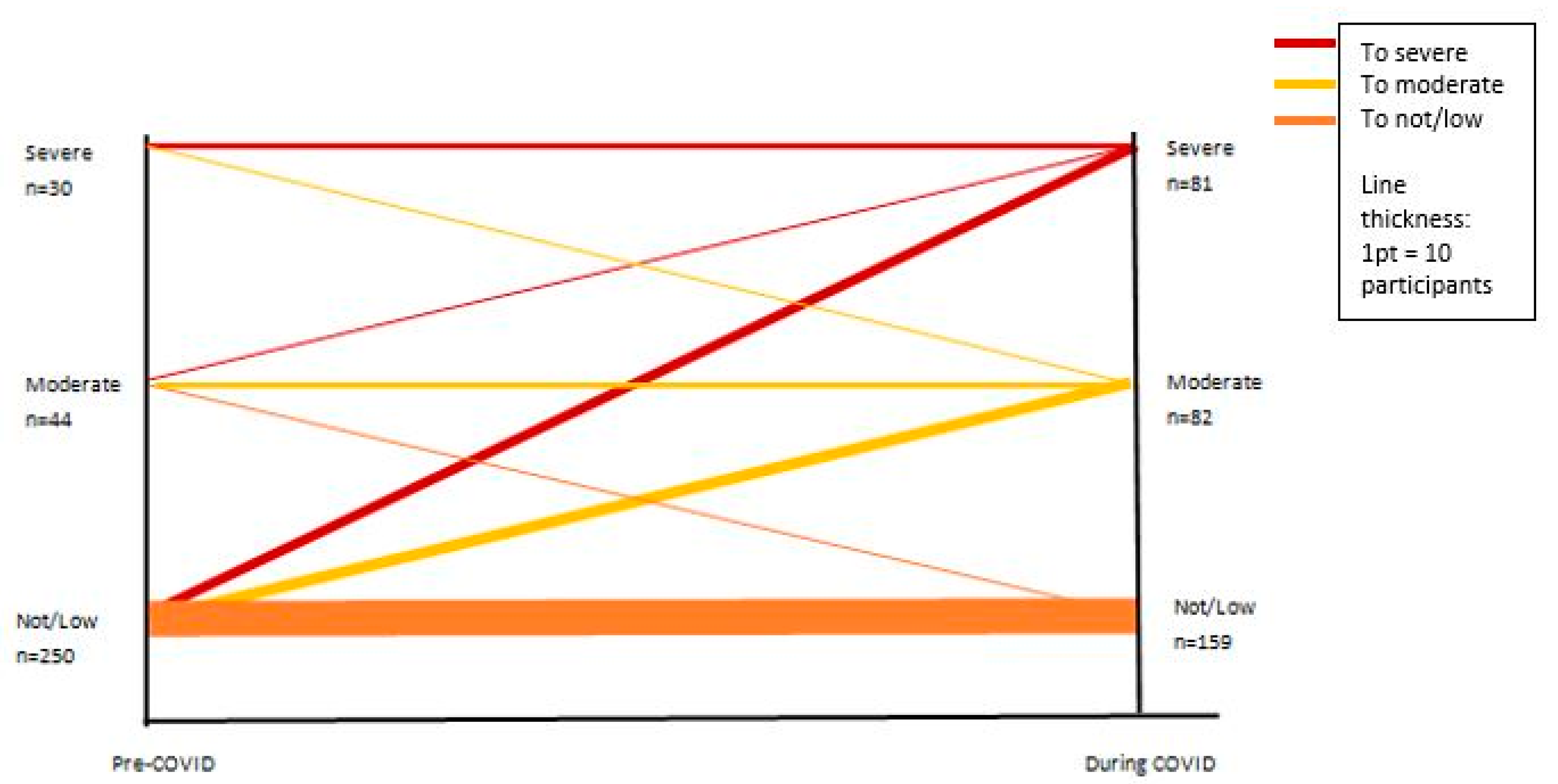

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy and Practice

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Intellectual Disability | Dementia | Mental Health | Physical Health | Intellectual Disability Multimorbid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | |

| 0: least Lonely | 90 | 27 | 864 | 245 | 202 | 69 | 518 | 181 | 62 | 23 |

| 53.6% | 16.1% | 55.4% | 15.7% | 51.9% | 17.9% | 54.5% | 19.2% | 44.6% | 16.5% | |

| 1 | 35 | 43 | 364 | 475 | 80 | 122 | 189 | 303 | 30 | 41 |

| 20.8% | 25.6% | 23.3% | 30.4% | 20.6% | 31.7% | 19.9% | 32.1% | 21.6% | 29.5% | |

| 2 | 26 | 52 | 203 | 490 | 54 | 93 | 130 | 234 | 21 | 39 |

| 15.5% | 31.0% | 13.0% | 31.4% | 13.9% | 24.2% | 13.7% | 24.8% | 15.1% | 28.1% | |

| 3: most Lonely | 17 | 46 | 128 | 351 | 53 | 101 | 113 | 226 | 26 | 36 |

| 10.1% | 27.4% | 8.2% | 22.5% | 13.6% | 26.2% | 11.9% | 23.9% | 18.7% | 25.9% | |

| Intellectual Disability | Dementia | Mental Health | Physical Health | Intellectual Disability Multimorbid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | |

| 0: least Lonely | 55 | 38 | 566 | 406 | 114 | 89 | 306 | 241 | 48 | 31 |

| 32.70% | 22.60% | 36.30% | 26.00% | 29.30% | 23.10% | 32.30% | 25.50% | 34.5% | 22.1% | |

| 1 | 14 | 15 | 110 | 172 | 39 | 31 | 72 | 77 | 11 | 10 |

| 8.30% | 8.90% | 7.10% | 11.00% | 10.00% | 8.10% | 7.60% | 8.20% | 7.90% | 7.1% | |

| 2 | 18 | 5 | 163 | 104 | 36 | 29 | 114 | 59 | 9 | 6 |

| 10.70% | 3.00% | 10.50% | 6.70% | 9.30% | 7.50% | 12.10% | 6.30% | 6.50% | 4.3% | |

| 3: most Lonely | 81 | 110 | 720 | 877 | 200 | 236 | 454 | 567 | 71 | 93 |

| 48.20% | 65.50% | 46.20% | 56.30% | 51.40% | 61.30% | 48.00% | 60.10% | 51.1% | 66.4% | |

References

- Grycuk, E.; Chen, Y.; Almirall-Sanchez, A.; Higgins, D.; Galvin, M.; Kane, J.; Kinchin, I.; Lawlor, B.; Rogan, C.; Russell, G.; et al. Care burden, loneliness, and social isolation in caregivers of people with physical and brain health conditions in English-speaking regions: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, D.; Peplau, L.A. Loneliness. In Encyclopedia of Mental Health; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.; Paul, G.; Fahy, M.; Dowling-Hetherington, L.; Kroll, T.; Moloney, B.; Duffy, C.; Fealy, G.; Lafferty, A. The invisible workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: Family carers at the frontline. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, M.; Czwikla, J.; Tsiasioti, C.; Schwinger, A.; Gand, D.; Schmiemann, G.; Schmidt, A.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Kloep, S.; Heinze, F. Differences in medical specialist utilization among older people in need of long-term care–results from German health claims data. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, S. Home alone revisited: Family caregivers providing complex care. Innov. Aging 2019, 3 (Suppl. S1), S747–S748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toljamo, M.; Perälä, M.-L.; Laukkala, H. Impact of caregiving on Finnish family caregivers. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 26, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.H. Emotional labor and organized emotional care: Conceptualizing nursing home care work. Work. Occup. 2006, 33, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Informal caregiving, loneliness and social isolation: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristol, A.A.; Chaudhry, S.; Assis, D.; Wright, R.; Moriyama, D.; Harwood, K.; Brody, A.A.; Charytan, D.M.; Chodosh, J.; Scherer, J.S. An exploratory qualitative study of patient and caregiver perspectives of ambulatory kidney palliative care. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 38, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindt, N.; van Berkel, J.; Mulder, B.C. Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, R.D.; Tmanova, L.L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, D.; Murphy, R.; McCallion, P.; Griffiths, M.M.; McCarron, M. Final Report September 2016; The University of Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, M.; Hatton, C.; Stansfield, J.; Cockayne, G. An audit of the well-being of staff working in intellectual disability settings in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2020, 25, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, L.; Truesdale-Kennedy, M.; Ryan, A.; McConkey, R. Examining the support needs of ageing family carers in developing future plans for a relative with an intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2012, 16, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsack-Topolewski, C.N.; Graves, J.M. “I worry about his future!” Challenges to future planning for adult children with ASD. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2020, 23, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumbusch, J.; Mayer, S.; Phinney, A.; Baumbusch, S. Aging together: Caring relations in families of adults with intellectual disabilities. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 57, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, D.; Murphy, R.; McCallion, P.; McCarron, M. “What’s going to happen when we’re gone?” Family caregiving capacity for older people with an intellectual disability in Ireland. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, A.; McCabe, L.; Watchman, K. Caring for older people with an intellectual disability: A systematic review. Maturitas 2012, 72, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.E.; Burke, M.M.; Perkins, E.A. Compound Caregiving: Toward a Research Agenda. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 60, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeste, S.; Hyde, C.; Distefano, C.; Halladay, A.; Ray, S.; Porath, M.; Wilson, R.B.; Thurm, A. Changes in access to educational and healthcare services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during COVID-19 restrictions. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020, 64, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, M.; Forbes, T.; Brown, M.; Marsh, L.; Truesdale, M.; McCann, E.; Todd, S.; Hughes, N. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family carers of those with profound and multiple intellectual disabilities: Perspectives from UK and Irish Non-Governmental Organisations. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2095. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, P.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Martínez, S.; Amor, A.M.; Crespo, M.; Deliu, M.M. Impact of COVID-19 on the burden of care of families of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 35, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, N.; Wiseman, P.; Watson, N.; Brunner, R.; Cullingworth, J.; Hameed, S.; Pearson, C.; Shakespeare, T. ‘Do they ever think about people like us?’: The experiences of people with learning disabilities in England and Scotland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Crit. Soc. Policy 2022, 02610183221109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M. The concept of care: Insights, challenges and research avenues in COVID-19 times. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2021, 31, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur-Sinai, A.; Bentur, N.; Fabbietti, P.; Lamura, G. Impact of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic on formal and informal care of community-dwelling older adults: Cross-national clustering of empirical evidence from 23 countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić, L.; Brkljačić, T.; Brajša-Žganec, A. Effects of COVID-19 related restrictive measures on parents of children with developmental difficulties. J. Child. Serv. 2020, 15, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintz, H.; Monette, P.; Epstein-Lubow, G.; Smith, L.; Rowlett, S.; Forester, B.P. Emerging collaborative care models for dementia care in the primary care setting: A narrative review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggleby, W.; Lee, H.; Nekolaichuk, C.; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D. Systematic review of factors associated with hope in family carers of persons living with chronic illness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3343–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, A.; Phillips, D.; Dowling-Hetherington, L.; Fahy, M.; Moloney, B.; Duffy, C.; Paul, G.; Fealy, G.; Kroll, T. Colliding worlds: Family carers’ experiences of balancing work and care in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 30, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yghemonos, S. Multidisciplinary policies and practices to support and empower informal carers in Europe. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Amati, R.; Albanese, E.; Fiordelli, M. Help-Seeking in Informal Family Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Qualitative Study with iSupport as a Case in Point. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doody, O.; Keenan, P.M. The reported effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with intellectual disability and their carers: A scoping review. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Noh, G.O.; Kim, K. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and family caregiver burden: A path analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Perez-Olivas, G.; Kroese, B.S.; Rogers, G.; Rose, J.; Murphy, G.; Cooper, V.; Langdon, P.E.; Hiles, S.; Clifford, C.; et al. The Experiences of Carers of Adults with Intellectual Disabilities During the First COVID-19 Lockdown Period. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 18, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willner, P.; Rose, J.; Stenfert Kroese, B.; Murphy, G.H.; Langdon, P.E.; Clifford, C.; Hutchings, H.; Watkins, A.; Hiles, S.; Cooper, V. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of carers of people with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, R.; Burns, A.; Leavey, G.; Leroi, I.; Burholt, V.; Lubben, J.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Victor, C.; Lawlor, B.; Vilar-Compte, M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Loneliness and Social Isolation: A Multi-Country Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer Society of Ireland. COVID-19: Impact & Need for People with Dementia and Family Carers; ASI: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gierveld, J.D.J.; Tilburg, T.V. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: Confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Aging 2006, 28, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging 2004, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Back-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubben, J.; Blozik, E.; Gillmann, G.; Iliffe, S.; von Renteln Kruse, W.; Beck, J.C.; Stuck, A.E. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurocarers/IRCCS-INRCA. Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Informal Carers Across Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Ancona, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, N.; Soto-Hernaez, J.; Williams, F.; Zhang, N.; Levy, R.; Scott, B.; Smailes, D.; Fox, J.; Jones, S. 975 A Thematic Analysis of the Experiences of Parents and Carers of Children in Hospital; BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, D.D.; Mannan, H.; Garcia Iriarte, E.; McConkey, R.; O’Brien, P.; Finlay, F.; Lawlor, A.; Harrington, G. Family voices: Life for family carers of people with intellectual disabilities in Ireland. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2013, 26, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, C.; Birkbeck, G.; Araten-Bergman, T.; Baumbusch, J.; Beadle-Brown, J.; Bigby, C.; Bradley, V.; Brown, M.; Bredewold, F.; Chirwa, M. COVID-19 IDD: Findings from a global survey exploring family members’ and paid staff’s perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and their caregivers. HRB Open Res. 2022, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, C.; Dalton, C.T. An exploration of care-burden experienced by older caregivers of adults with intellectual disabilities in Ireland. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2019, 47, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroi, I.; McDonald, K.; Pantula, H.; Harbishettar, V. Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson Disease: Impact on Quality of Life, Disability, and Caregiver Burden. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2012, 25, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, M.; Bhatia, S.; Gautam, P.; Saha, R.; Kaur, J. Burden assessment, psychiatric morbidity, and their correlates in caregivers of patients with intellectual disability. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 25, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chou, Y.; Pu, C.Y.; Fu, L.Y.; Kröger, T. Depressive symptoms in older female carers of adults with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-J.; Park, E.-Y. Relationship between caregiving burden and depression in caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities in Korea. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Peters, T.J. Caring for elderly dependants: Effects on the carers’ quality of life. Age Ageing 1992, 21, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intellectual Disability n = 227 | Dementia n = 1888 | Physical Disability n = 1147 | Mental Health n = 491 | Intellectual Disability Multimorbid n = 177 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 82.4% | 77.0% | 80.4% | 77.4% | 80.2% |

| Age 55+ | † 47.3% | * 67.2% | 53.5% | † 41.7% | 50.3% |

| Marital status (married/cohabiting) | 67.7% | * 74.8% | 67.7% | † 59.4% | 65.9% |

| Religion very important | 28.8% | 30.7% | 31.2% | 29.7% | 30.7% |

| Third Level education | 64.4% | 70.5% | 73.8% | 74.8% | 70.4% |

| Poor physical health | 21.6% | 17.6% | 16.1% | 20.5% | * 27.2% |

| Poor mental health | * 28.4% | 21.0% | 19.4% | 22.7% | * 32.1% |

| Finances meet needs poorly | * 16% | 11.0% | 12.4% | 16.0% | * 21.7% |

| Care for child | * 31.3% | † 0.0% | 6.3% | * 12.0% | * 24.9% |

| Burdened by caring role quite frequently | 37.8% | * 42.2% | † 25.2% | † 26.4% | 41.7% |

| Covid burden change more than usual | * 65.1% | * 60.1% | † 47.9% | † 44.4% | 62.8% |

| Intellectual Disability n = 175 | Dementia n = 1644 | Mental Health n = 404 | Physical Health n = 988 | Intellectual Disability Multimorbid n = 149 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | Pre | During | |

| 1: None/low | 81.1% | 52.9% | 78.3% | 48.2% | 76.7% | 52.7% | 79.7% | 54.0% | 72.5% | 45.3% |

| 2: Moderate | 12.6% | 31.0% | 14.7% | 24.7% | 15.1% | 28.4% | 15.0% | 25.2% | 14.8% | 18.9% |

| 3: Severe | 6.3% | 16.1% | 7.1% | 27.1% | 8.2% | 18.9% | 5.4% | 20.9% | 12.8% | 35.8% |

| B | AOR | Std. Error | p | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender Female (reference) | ||||||

| Gender Male | −0.087 | 0.917 | 0.499 | 0.848 | −1.183 | 0.787 |

| Age 18–34 (reference) | ||||||

| Age 35–44 | 0.463 | 1.589 | 2.479 | 0.500 | −0.897 | 2.505 |

| Age 45–54 | −0.772 | 0.462 | 2.652 | 0.294 | −2.473 | 1.323 |

| Age 55–69 | 0.008 | 1.008 | 2.457 | 0.974 | −1.211 | 1.865 |

| Age 70 and over | 0.500 | 1.649 | 2.481 | 0.460 | −0.938 | 2.441 |

| Physical Health Good/Excellent (reference) | ||||||

| Physical Health Fair/Poor | −0.272 | 0.762 | 0.466 | 0.525 | −1.269 | 0.552 |

| Mental Health Good/Excellent (reference) | ||||||

| Mental Health Fair/Poor | 0.785 | 2.192 | 0.415 | 0.034 * | 0.007 | 1.626 |

| Work Status Not Working (reference) | ||||||

| Work Status Working | −0.501 | 0.606 | 0.424 | 0.205 | −1.43 | 0.254 |

| Burdened Never (reference) | ||||||

| Burdened Rarely | 1.482 | 4.401 | 8.775 | 0.084 | −0.229 | 20.027 |

| Burdened Sometimes | 0.655 | 1.925 | 8.814 | 0.279 | −1.109 | 19.183 |

| Burdened Frequently | 1.896 | 6.661 | 8.808 | 0.049 * | 0.266 | 20.508 |

| Burdened Always | 2.766 | 15.897 | 8.808 | 0.012 ** | 0.967 | 21.648 |

| Constant | −3.032 | 0.048 | 9.016 | 0.002 | −21.906 | −1.578 |

| B | AOR | Std. Error | p | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Food consumption About the same (reference) | ||||||

| Food consumption Less than before | −0.201 | 0.818 | 0.688 | 0.737 | −1.692 | 0.991 |

| Food consumption More than before | 0.107 | 1.112 | 0.416 | 0.787 | −0.706 | 0.918 |

| Sleep patterns About the same (reference) | ||||||

| Sleep patterns Less than before | 0.846 | 2.330 | 2.799 | 0.238 | −1.371 | 2.477 |

| Sleep patterns More than before | 0.754 | 2.125 | 0.448 | 0.064 | −0.022 | 1.76 |

| Physical activity About the same (reference) | ||||||

| Physical activity Less than before | 0.797 | 2.218 | 0.521 | 0.085 | −0.099 | 1.992 |

| Physical activity More than before | 1.054 | 2.869 | 0.729 | 0.071 | −0.186 | 2.483 |

| Mental health About the same (reference) | ||||||

| Mental health Better than before | −17.921 | 0.000 | 1.817 | 0.999 | −19.292 | −15.09 |

| Mental health Worse than before | 2.322 | 10.192 | 1.607 | 0.000 ** | 1.514 | 4.099 |

| Cultural activities About the same (reference) | ||||||

| Cultural activities Less than before | −0.004 | 0.996 | 0.419 | 0.989 | −0.868 | 0.785 |

| Cultural activities More than before | −0.319 | 0.727 | 0.697 | 0.530 | −1.629 | 0.685 |

| Constant | −4.487 | 0.011 | 1.654 | 0.000 | −6.698 | −3.575 |

| B | AOR | Std. Error | p | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender Female (reference) | ||||||

| Gender Male | 0.329 | 1.39 | 0.414 | 0.393 | −0.456 | 1.163 |

| Age 18 to 34 (reference) | ||||||

| Age 35 to 44 | 0.027 | 1.027 | 0.665 | 0.962 | −1.218 | 1.391 |

| Age 45 to 54 | 1.032 | 2.806 | 0.612 | 0.060 | −0.02 | 2.377 |

| Age 55 to 69 | 0.986 | 2.681 | 0.583 | 0.056 | −0.005 | 2.276 |

| Age 70+ | 0.445 | 1.561 | 0.691 | 0.483 | −0.82 | 1.901 |

| Never Burdened (reference) | ||||||

| Rarely Burdened | −0.437 | 0.646 | 0.821 | 0.467 | −1.87 | 0.76 |

| Sometimes Burdened | −1.097 | 0.334 | 0.77 | 0.029 | −2.489 | −0.117 |

| Frequently Burdened | −1.856 | 0.156 | 0.803 | 0.001 ** | −3.351 | −0.849 |

| Always Burdened | −1.602 | 0.202 | 1.081 | 0.015 * | −3.385 | −0.33 |

| Poor Physical Health (reference) | ||||||

| Excellent Physical Health | 0.541 | 1.718 | 0.44 | 0.182 | −0.266 | 1.465 |

| Poor Mental Health (reference) | ||||||

| Excellent Mental Health | 1.13 | 3.096 | 0.437 | 0.004 ** | 0.409 | 2.111 |

| Isolated (reference) | ||||||

| Not Isolated | 0.566 | 1.761 | 0.389 | 0.116 | −0.178 | 1.353 |

| Constant | −1.443 | 0.236 | 0.997 | 0.054 | −3.238 | 0.163 |

| AOR | Std. Error | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender Male (reference) | ||||||

| Gender Female | 0.630 | 1.878 | 0.438 | 0.114 | −0.141 | 1.597 |

| Age: 18–34 (reference) | ||||||

| Age: 35–44 | 1.443 | 4.235 | 1.553 | 0.012 * | 0.261 | 3.157 |

| Age: 45–54 | 1.420 | 4.136 | 1.539 | 0.010 * | 0.333 | 3.138 |

| Age 55–69 | 1.145 | 3.141 | 1.523 | 0.036 * | 0.117 | 2.852 |

| Age: 70 and over | 0.739 | 2.094 | 1.566 | 0.279 | −0.599 | 2.471 |

| Mental Health good/excellent | ||||||

| Mental Health fair/poor | 1.255 | 3.508 | 0.349 | 0.000 ** | 0.66 | 2.013 |

| Lubben Social Network: Not Isolated (reference) | ||||||

| Lubben Social Network: Isolated | −0.206 | 0.814 | 0.368 | 0.549 | −0.959 | 0.468 |

| UCLA pre-COVID-19: Low | ||||||

| UCLA pre-COVID-19: Moderate | −0.062 | 0.940 | 0.505 | 0.897 | −1.141 | 0.877 |

| UCLA pre-COVID-19: Severe | 0.914 | 2.494 | 0.505 | 0.040 * | 0.022 | 2.000 |

| Constant | −2.627 | 0.072 | 1.525 | 0.000 | −4.412 | −1.629 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wormald, A.; McGlinchey, E.; D’Eath, M.; Leroi, I.; Lawlor, B.; McCallion, P.; McCarron, M.; O’Sullivan, R.; Chen, Y. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Caregivers of People with an Intellectual Disability, in Comparison to Carers of Those with Other Disabilities and with Mental Health Issues: A Multicountry Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043256

Wormald A, McGlinchey E, D’Eath M, Leroi I, Lawlor B, McCallion P, McCarron M, O’Sullivan R, Chen Y. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Caregivers of People with an Intellectual Disability, in Comparison to Carers of Those with Other Disabilities and with Mental Health Issues: A Multicountry Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043256

Chicago/Turabian StyleWormald, Andrew, Eimear McGlinchey, Maureen D’Eath, Iracema Leroi, Brian Lawlor, Philip McCallion, Mary McCarron, Roger O’Sullivan, and Yaohua Chen. 2023. "Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Caregivers of People with an Intellectual Disability, in Comparison to Carers of Those with Other Disabilities and with Mental Health Issues: A Multicountry Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043256

APA StyleWormald, A., McGlinchey, E., D’Eath, M., Leroi, I., Lawlor, B., McCallion, P., McCarron, M., O’Sullivan, R., & Chen, Y. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Caregivers of People with an Intellectual Disability, in Comparison to Carers of Those with Other Disabilities and with Mental Health Issues: A Multicountry Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043256