Excessive Food Buying in Saudi Arabia Amid COVID-19: Examining the Effects of Perceived Severity, Religiosity, Consumption Culture and Attitude toward Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

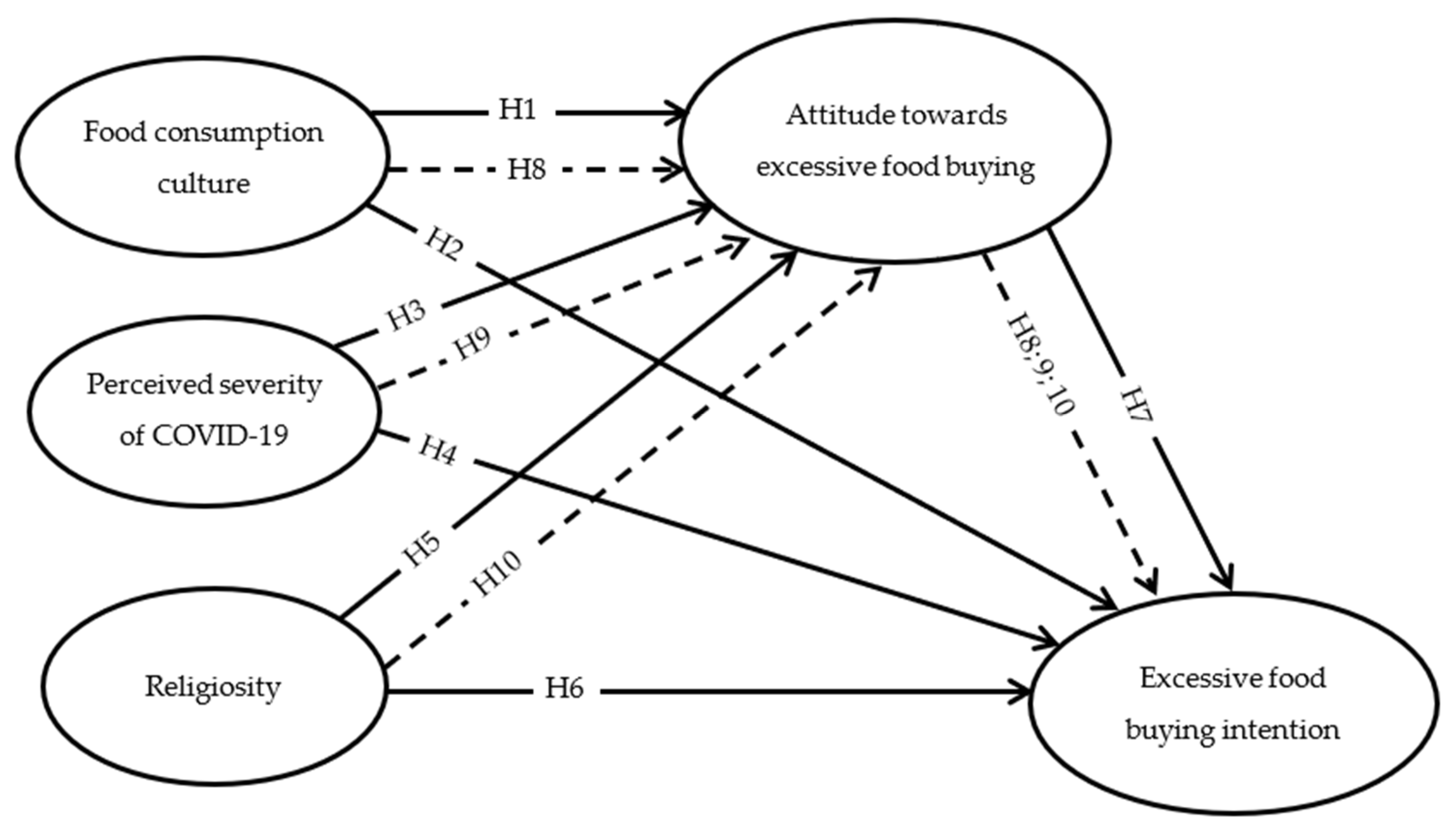

2. Hypotheses Building

2.1. Food Consumption Culture, Attitudes toward Behavior, and Excessive Food Buying

2.2. Perceived Severity, Attitudes toward Behavior, and Excessive Food Buying

2.3. Religiosity, Attitudes toward Behavior, and Excessive Food Buying

2.4. The Relationship between Attitude toward Behavior and Excessive Buying Intention

2.5. The Mediating Effect of Attitude toward Behavior on the Link between Food Consumption Culture, Perceived Severity, Religiously, and Excessive Food-Buying Intention

3. Methods

3.1. The Research Instrument

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection Process

3.3. Data Analysis Technique

4. Results

4.1. Respondets’ Demographics

4.2. The Measurement Model

4.3. The Research Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Implications of the Study

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Religiosity | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| R_1 | I believe in God | Minton et al. [46] |

| R_2 | I have no doubts that God lives and is real | |

| R_3 | There is life after death | |

| R_4 | The scripture for my religious affiliation is the word of God | |

| Food consumption culture | Aktas et al. [45] | |

| FCC_1 | It is my culture to serve a lot of food to show my hospitality | |

| FCC_2 | I have a tendency to buy a few more food products than I need at the restaurant | |

| FCC_3 | I serve more food than can be eaten to show my hospitality | |

| Excessive food-buying intention | Neff et al. [47] | |

| EFB_1 | I intend to purchase larger quantities of food than we currently require, when there are quantity discounts, | |

| EFB_2 | I intend to purchase food items that we already had at home | |

| EFB_3 | I intend to purchase items that were not on our shopping list | |

| Perceived Severity | Omar et al. [10] | |

| PS_1 | COVID-19 pandemic is a serious threat | |

| PS_2 | COVID-19 pandemic is critical | |

| PS_3 | COVID-19 pandemic is a life-threatening | |

| Attitude toward behavior | Ajzen [38] | |

| A_1 | I feel good when I buy more food than needed | |

| A_2 | I was raised to believe that I should have more food at home | |

| A_3 | I think I should buy as much food as I can | |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO. Food Loss and Food Waste. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- United Nations Development Program UNDP. Food Waste Index Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- United Nations Development Program UNDP. Food For Thought: Why Is Food Waste a Challenge in Saudi Arabia? Available online: https://www.undp.org/saudi-arabia/blog/food-thought-why-food-waste-challenge-saudi-arabia (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- SAGO. Saudi FLW Baseline: Food Loss and Waste Index in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; Saudi Grains Organization Riyadh: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AlFadley, A.A.A. Food Waste Costs Saudi Arabia SR40 Billion Annually. Available online: https://mewa.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News242020.aspx (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Baig, M.B.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Alzahrani, K.; Pearson, D.; Alshammari, G.M.; Shah, A.A. Food Waste in Saudi Arabia: Causes, Consequences, and Combating Measures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.B.; Al-Zahrani, K.H.; Schneider, F.; Straquadine, G.S.; Mourad, M. Food waste posing a serious threat to sustainability in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A systematic review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azazz, A.M.S.; Elshaer, I.A. Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic, Social Media Usage and Food Waste Intention: The Role of Excessive Buying Behavior and Religiosity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Zhu, G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.A.; Nazri, M.A.; Ali, M.H.; Alam, S.S. The panic buying behavior of consumers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining the influences of uncertainty, perceptions of severity, perceptions of scarcity, and anxiety. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Farooq, A.; Dhir, A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Moustafa, F. Panic Food Purchasing amid COVID-19 Pandemic: Does the Impact of Perceived Severity, Anxiety and Self-Isolation Really Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Li, K.X. The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotzke, P.; Starcke, K.; Müller, A.; Brand, M. Pathological buying online as a specific form of internet addiction: A model-based experimental investigation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshaer, I.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Alyahya, M.; Abu Elnasr, A. The Impact of Religiosity and Food Consumption Culture on Food Waste Intention in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioural Control, Self-efficacy, Locus of Control and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourst, L. Food Culture: Tradition and Modernity in Conflict. Food: Work and Culture; SIFO Delrapport 4 Mat: Arbeid og Kultur [Food: Work and Culture]; National Institute for Consumer Research: Lysaker, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrios, M.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Ali, K.; Maclean, B.; Moulding, R. Predicting the severity of excessive buying using the excessive buying rating scale and compulsive buying scale. J. Obs. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2020, 25, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasha, L.; Molelekwa, G.F.; Mokgobu, M.I.; Morodi, T.J.; Mokoena, M.M.; Mudau, L.S. Influence of cultural practices on food waste in South Africa—A review. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaiger, A.O. Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting food consumption patterns in the Arab countries. J. R. Soc. Health 1993, 113, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, P.; Misnad, S. Sustainable Development: An Appraisal Focusing on the Gulf Region; Berghan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vitell, S.; Ramos-Hidalgo, E.; Rodríguez-Rad, C. A Spanish perspective on the impact on religiosity and spirituality on consumer ethics. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayat, I. Arab Countries Face Problem of Food Waste during Ramadan. The Arab Weekly 2017. Available online: https://thearabweekly.com/arab-countries-face-problem-food-waste-during-ramadan (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Sneath, J.Z.; Lacey, R.; Kennett-Hensel, P.A. Coping with a natural disaster: Losses, emotions, and impulsive and compulsive buying. Mark. Lett. 2009, 20, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennett-Hensel, P.A.; Sneath, J.Z.; Lacey, R. Liminality and consumption in the aftermath of a natural disaster. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngunjiri, F. The challenge of inclusion in the ethics classroom. Intersections 2020, 2020, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Miri, S.M.; Roozbeh, F.; Omranirad, A.; Alavian, S.M. Panic of buying toilet papers: A historical memory or a horrible truth? Systematic review of gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19. Hepat. Mon. 2020, 20, e102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, B.; Xiong, H.; Shen, X. Consumer panic buying and quota policy under supply disruptions. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xin, L.; Li, D.; Yu, J.; Guo, J. How does scarcity promotion lead to impulse purchase in the online market? A field experiment. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani, M.H.; Kazemi, A.; Ranjbarian, B. Religion, Peculiar Beliefs and Luxury Cars’ Consumer Behavior in Iran. J. Islamic Mark. 2019, 10, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakrachakarn, V.; Moschis, P.; Ong, S.; Shannon, R. Materialism and life satisfaction: The role of religion. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ansari, S. Improving solid waste management in gulf co-operation council states: Developing integrated plans to achieve reduction in greenhouse gases. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2012, 62, 376–387. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.; Shahbaz, S. The Relationship between Religiosity and New Product Adoption. J. Islam. Mark. 2010, 1, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysseldyk, R.; Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion from a Social IdentityPerspective. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, A.; Johnson, A.; Liu, L. Religiosity and special food consumption: The explanatory effects of moral priorities. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, S.; Morwitz, V.G. Effects of participative pricing on consumers’ cognitions and actions: A goal theoretic perspective. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis): New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Talwar, M.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Tripathy, N.; Dhir, A. Has financial attitude impacted the trading activity of retail investors during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Sadiq, M.; Talwar, S.; Sakashita, M.; Kaur, P. Why do retail consumers buy green apparel? A knowledge-attitude-behaviour-context perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.C.; Bateman, C.R. Consumer religious commitment’s influence on ecocentric attitudes and behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, M.; Mutum, S.; Ariswibowo, N. Impact of religious values and habit on an extended green purchase behavior model. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, E.; Sahin, H.; Topaloglu, Z.; Oledinma, A.; Huda, S.; Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M.; van’t Wout, T.; Kamrava, M. A consumer behavioural approach to food waste. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.A.; Xie, H.J.; Gurel-Atay, E.; Kahle, L.R. Greening up because of god: The relations among religion, sustainable consumption and subjective well-being. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.L.; Truant, P.L. Wasted Food: U.S. Consumers’ Reported Awareness, Attitudes, and Behaviors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Mathur, A. The value of online surveys. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method. Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Aldaco, R.; Hoehn, D.; Laso, J.; Margallo, M.; Ruiz-Salmón, J.; Cristobal, J.; Kahhat, R.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; Bala, A.; Batlle-Bayer, L.; et al. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: A holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, M.; Verneau, F.; Coppola, A.; La Barbera, F. Domestic food waste and Covid-19 concern: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Ogarca, R.F.; Barbu, C.M.; Craciun, L.; Baloi, I.C.; Mihai, L.S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food waste behaviour of young people. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Franko, D.L.; Omori, M.; Linardon, J.; Guillaume, S.; Fischer, L.; Tyszkiewicz, M.F. “Waste not and stay at home” evidence of decreased food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic from the US and Italy. Appetite 2021, 160, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dimensions/Variables | Loadings | a Value | C.R | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.703 | 0.701 | 0.605 | |

| A_1 | 0.798 | |||

| A_2 | 0.825 | |||

| A_3 | 0.707 | |||

| Excessive Buying Intention | 0.883 | 0.889 | 0.811 | |

| EFB_2 | 0.933 | |||

| EFB_3 | 0.884 | |||

| EFB_2 | 0.884 | |||

| Food Consumption Culture | 0.702 | 0.708 | 0.618 | |

| FCC_1 | 0.823 | |||

| FCC_2 | 0.818 | |||

| FCC_3 | 0.712 | |||

| Perceived Severity | 0.924 | 0.937 | 0.869 | |

| PS_1 | 0.935 | |||

| PS_2 | 0.900 | |||

| PS_3 | 0.960 | |||

| Religiosity | 0.937 | 0.938 | 0.842 | |

| R_1 | 0.922 | |||

| R_2 | 0.893 | |||

| R_3 | 0.897 | |||

| R_4 | 0.956 |

| Attitude | Excessive Buying Intention | Food Consumption Culture | Perceived Severity | Religiosity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_1 | 0.798 | 0.486 | 0.684 | 0.349 | 0.436 |

| A_2 | 0.825 | 0.396 | 0.690 | 0.238 | 0.263 |

| A_3 | 0.707 | 0.379 | 0.583 | 0.288 | 0.231 |

| EFB_1 | 0.546 | 0.933 | 0.474 | 0.409 | 0.292 |

| EFB_2 | 0.478 | 0.884 | 0.376 | 0.349 | 0.261 |

| EFB_3 | 0.440 | 0.884 | 0.335 | 0.323 | 0.442 |

| FCC_1 | 0.714 | 0.401 | 0.823 | 0.288 | 0.309 |

| FCC_2 | 0.656 | 0.317 | 0.818 | 0.187 | 0.224 |

| FCC_3 | 0.607 | 0.316 | 0.712 | 0.174 | 0.243 |

| PS_1 | 0.393 | 0.402 | 0.240 | 0.935 | 0.362 |

| PS_2 | 0.300 | 0.331 | 0.250 | 0.900 | 0.150 |

| PS_3 | 0.351 | 0.384 | 0.293 | 0.960 | 0.237 |

| R_1 | 0.388 | 0.298 | 0.350 | 0.189 | 0.922 |

| R_2 | 0.340 | 0.348 | 0.299 | 0.132 | 0.893 |

| R_3 | 0.396 | 0.343 | 0.301 | 0.354 | 0.897 |

| R_4 | 0.367 | 0.354 | 0.268 | 0.327 | 0.956 |

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | Heterotrait/Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)—Matrix | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1-Attitude | 0.778 | |||||||||

| 2-Excessive Buying Intention | 0.544 | 0.901 | 0.699 | |||||||

| 3-Food Consumption Culture | 0.541 | 0.442 | 0.786 | 0.232 | 0.560 | |||||

| 4-Perceived Severity | 0.377 | 0.402 | 0.280 | 0.932 | 0.472 | 0.440 | 0.346 | |||

| 5-Religiosity | 0.407 | 0.367 | 0.331 | 0.276 | 0.917 | 0.502 | 0.405 | 0.411 | 0.285 | |

| Endogenous Variables | (R2) | (Q2) |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.741 | 0.722 |

| Excessive Buying Intention | 0.358 | 0.286 |

| Model Fit | SRMR | NFI |

| 0.044 | 0.902 |

| Relationships | Beta (β) | (t-Value) | p Values | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Food Consumption Culture -> Attitude | 0.766 | 17.318 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | Food Consumption Culture -> Excessive Buying Intention | −0.021 | 0.242 | 0.809 | Not Accepted |

| H3 | Perceived Severity -> Attitude | 0.130 | 2.971 | 0.003 | Accepted |

| H4 | Perceived Severity -> Excessive Buying Intention | 0.208 | 4.450 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5 | Religiosity -> Attitude | 0.117 | 2.807 | 0.005 | Not Accepted |

| H6 | Religiosity -> Excessive Buying Intention | 0.143 | 2.245 | 0.025 | Not Accepted |

| H7 | Attitude -> Excessive Buying Intention | 0.425 | 4.686 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H8 | Food Consumption Culture -> Attitude -> Excessive Buying Intention | 0.326 | 4.432 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H9 | Perceived Severity -> Attitude -> Excessive Buying Intention | 0.055 | 2.941 | 0.003 | Accepted |

| H10 | Religiosity -> Attitude -> Excessive Buying Intention | 0.050 | 2.430 | 0.015 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sobaih, A.E.E. Excessive Food Buying in Saudi Arabia Amid COVID-19: Examining the Effects of Perceived Severity, Religiosity, Consumption Culture and Attitude toward Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043126

Sobaih AEE. Excessive Food Buying in Saudi Arabia Amid COVID-19: Examining the Effects of Perceived Severity, Religiosity, Consumption Culture and Attitude toward Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043126

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobaih, Abu Elnasr E. 2023. "Excessive Food Buying in Saudi Arabia Amid COVID-19: Examining the Effects of Perceived Severity, Religiosity, Consumption Culture and Attitude toward Behavior" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043126

APA StyleSobaih, A. E. E. (2023). Excessive Food Buying in Saudi Arabia Amid COVID-19: Examining the Effects of Perceived Severity, Religiosity, Consumption Culture and Attitude toward Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043126