Superheroes or Super Spreaders? The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Attitudes towards Nurses: A Qualitative Study from Poland †

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What social reactions did nurses face during the pandemic?

- Has the pandemic changed the social perception of nurses?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Issues

2.4. Data Analysis

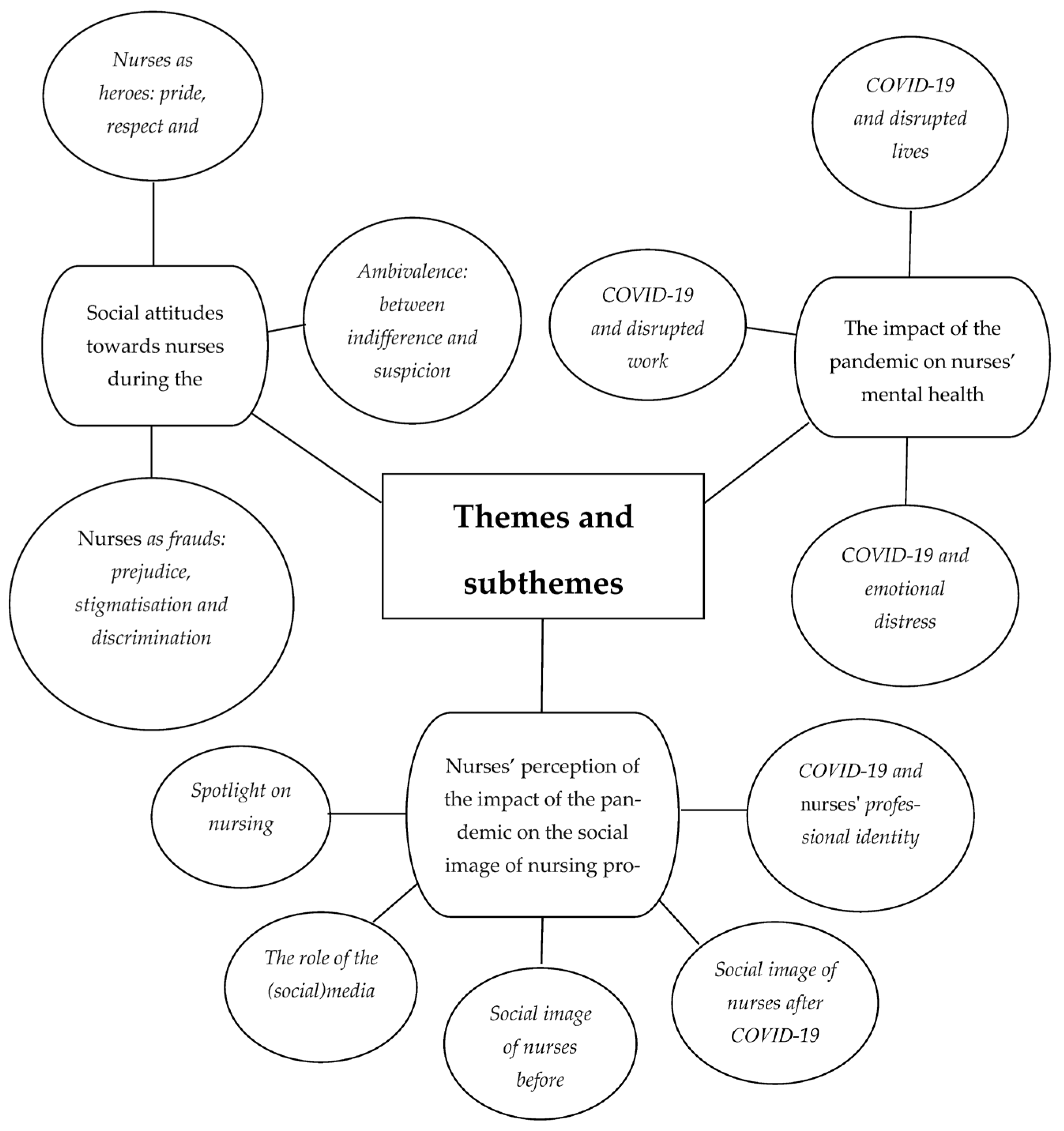

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Findings

3.2.1. Social Attitudes towards Nurses during the Pandemic

Nurses as Heroes: Pride, Respect and Admiration

I will never forget the moment an older woman, the same age as my grandmother, thanked me for every word, every gesture toward her. When she recovered and was discharged, she gave me her address and invited me for a delicious dessert because she wanted to thank me. I felt such gratitude and appreciation, and it has helped me to manage all these emotions and all the hard work.(N8)

It was nice when my neighbour, an older lady, came to me with a cake and said that without us there would be nothing. I was really moved by that.(N10)

I was working in a temporary hospital at Poznań International Fair. Once an older patient who was in a really bad state grabbed my hand and said, “My child, thank you from the bottom of my heart. If not for you, I would be long gone”. Such words gave me strength, even though there were moments when I wanted to leave it all and just rest.(N15)

Ambivalence: Between Indifference and Suspicion

My grandmother was constantly saying, “My child, let it go, you are young, you have your whole life ahead of you. They will manage without you. You have a family, a child, a husband”.(N6)

At the beginning my relatives were more afraid of me than the pandemic itself [laughs]. They avoided contact with me. We even spent Easter apart. And the higher the number of infections, the greater their fear.(N7)

Nurses as Frauds: Prejudice, Stigmatisation and Discrimination

I felt very sad when I heard in a shop that medics and pensioners are privileged because we could do our shopping without queueing. One lady called us “parasites”. I did not even enter into a discussion because I was afraid that those people would point at me.(N7)

From the very beginning my uncle was very sceptical. He sniffed out a conspiracy and argued that the medics are frauds, not heroes. That hurt a lot, especially when I came home from twenty-four hour shifts, filled with the chaos of people dying in our arms, and others seeking out a conspiracy.(N3)

When my sister-in-law found out that I had been vaccinated, she told me that we couldn’t meet, as the vaccinations could affect her, as they contained heavy metals that would be deposited in the brain.(N12)

The worst thing I have ever heard was that I was doing it all for the money!.(N2)

One thing stuck in my memory: “How are you doing with the double salary paid from my taxes? There are more important expenditures! You should not get a penny for it. It’s all a scam!”.(N9)

There were many disparaging comments about us on Facebook, especially under daily reports on the infection rate published by the Ministry of Health. It could be depressing, as people were very cruel, even heartless toward nurses, doctors and paramedics.(N5)

Some did not believe that people were really dying in the hospitals. Others thought that the image was created for TV. (…) I remember one such terse comment. One man wrote under the article: “They did not save my mother, I wish them the same”. Since then I have stopped reading comments.(N13)

3.2.2. Nurses’ Perception of the Impact of the Pandemic on the Social Image of the Nursing Profession

Spotlight on Nursing

Yes, during that time we were in the public eye. Our every move was commented on, and every stumble was pointed out.(N13)

The Role of (Social) Media

Nurses are not nuns! Those times are long gone. Neither are we “piguła” [Polish for pill, a pejorative term for nurses]. I hate that term.(N5)

TV series have a huge influence on social respect towards nurses. I have often seen nurses depicted in skimpy outfits. Does it help? Of course not! We really have expertise, a great deal of responsibility, and the last thing we think of is parading about in short skirts, as some people seem to think.(N6)

Social Image of Nurses before COVID-19

POZ [Basic Health Care] is bad for our image, as patients often think that a nurse is simply a person who works in registration.(N11)

People do not know that in order to become a nurse you have to graduate from university. Once, when I was doing my practical training on a ward I was asked by a lady what I was doing there. When I told her that I was doing my practical training because I was studying nursing, she was very surprised. “Do you have to study for that? I thought that a regular course was enough”, she said.(N14)

Social Image of Nurses after COVID-19

For the very first time, after 25 years, I have heard somebody acknowledge my work. Just thinking about it brings tears to my eyes, as I hope that it [the pandemic] will finally change the image of Polish nurses.(N5)

When I was working on the COVID ward, during one shift a man of 36 thanked me for everything. He said that nurses were doing a great job and should be lauded for that. I talked with him for a moment and he admitted that his previous experiences were poor, but now he realised what it was like and he appreciated our work.(N12)

People have finally realised that nursing is an independent and responsible profession, and not only one of “pass it; bring it” to a doctor”.(N7)

Thanks to the pandemic our profession has become more independent (…). During one shift I heard a conversation between a nurse and a patient, who told her that the pandemic had made him realise how much work we have, how much we know and how little we are acknowledged.(N11)

COVID-19 and Nurses’ Professional Identity

In my opinion, it [COVID-19] had a beneficial influence on us. It has strengthened our belief that what we do is good, necessary and that without us the entire system would collapse.(N3)

It was hard to enter the profession at such a difficult time. It made tough and inured me a great deal. Now I simply do my thing.(N13)

3.2.3. The Impact of the Pandemic on Nurses’ Mental Health

COIVD-19 and Disrupted Lives

I have not known anxiety disorder before (…). I have never experienced it before. Me? No way. Such a strong woman! All my strength disappeared when COVID emerged around me, and then came death. How can you accept the death of a person who was the picture of health just few days before (…) That’s why I began to see a psychiatrist.(N13)

My mental health deteriorated, but I am no longer afraid to talk about it. However, in the beginning I didn’t want to admit that this whole situation overwhelmed me completely; and yes, I felt in danger, like I was standing next to a bomb that could explode at any second.(N1)

COIVD-19 and Disrupted Work

Apart from the fear about the health of my relatives I was burdened by the awareness that I was the head of the family and have to bring in the money (…) My wife was pregnant back then and I felt a great responsibility.(N2)

Do you know the feeling that you have the weight of the world on your shoulders? There was a moment on my ward, when, except for me, only two nurses were healthy and not quarantined. It was a nightmare. I thought that I would soon be next. We were alone during the shifts, working 24 h. And back then it was my first job. What is even worse, I had just been working for five months. I always brought a big bag full of things with me, as you didn’t know what would happen that day.(N14)

I work in the emergency unit and it affected us a lot. They called us to literally everything, but people would not tell us when they were infected.(N9)

Why did they want to protect doctors and nurses working in Primary Healthcare (POZ), but not us?.(N13)

COIVD-19 and Emotional Distress

Eight months of constant stress, watching all the news. The wave of distressing information pounded us. I could not sit still and grew nervous more easily. I felt like a ticking bomb. And this stress infected my children.(N6)

I was seriously stressed by constantly watching the news: how many people were infected every day; how many had died, etc. As these numbers increased my anxiety grew proportionally.(N12)

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Policy and Practice

- While the COVID-19 outbreak has helped raise social awareness of the role of nurses in the healthcare system, there is an urgent need for public communication and the promotion of a more truthful image of nursing in society.

- As working during the outbreak was physically and emotionally challenging, special attention must be paid to HCPs’ safety, and they must be provided with both the necessary personal protective equipment and mental health support.

- Nurses and HCPs in general should be better prepared for future global health crises and medical disasters, emergency decision making, coping and leadership during a crisis by medical curricula.

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Haldane, V.; De Foo, C.; Abdalla, S.M.; Jung, A.S.; Tan, M.; Wu, S.; Chua, A.; Verma, M.; Shrestha, P.; Singh, S.; et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from 28 countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawaz, M.; Anshasi, H.; Samaha, A. Nurses at the front line of COVID-19: Roles, responsibilities, risks, and rights. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1341–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kako, J.; Kajiwara, K. Scoping review: What is the role of nurses in the era of the global COVID-19 pandemic? J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 1566–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemali, S.; Mari-Sáez, A.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Weishaar, H. Health care workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Health 2022, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerstwo Zdrowia. Pierwszy Przypadek Koronawirusa w Polsce. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/pierwszy-przypadek-koronawirusa-w-polsce (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Ustawa z Dnia 18 Kwietnia 2002 r. o Stanie Klęski Żywiołowej. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20020620558 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Puls Medycyny. Pierwszy Zgon z Powodu Koronawirusa w Polsce. 2020. Available online: https://pulsmedycyny.pl/pierwszy-zgon-z-powodu-koronawirusa-w-polsce-984842 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Ministerstwo Zdrowia. Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 20 marca 2020 r. w Sprawie Ogłoszenia na Obszarze Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Stanu Epidemii. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rpa/rozporzadzenie-ministra-zdrowia-z-dnia-20-marca-2020-r-w-sprawie-ogloszenia-na-obszarze-rzeczypospolitej-polskiej-stanu-epidemii (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Gniadek, A. Polska pielęgniarka w czasie pandemii zakażeń SARS-CoV-2. Zdr. Publ. Zarz. 2020, 18, 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska-Lipień, I.; Wadas, T.; Gabryś, T.; Kózka, M.; Gniadek, A.; Brzostek, T.; Squires, A. Evaluating Polish nurses’ working conditions and patient safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2022, 69, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naczelna Izba Pielęgniarek i Położnych. Informacja Ministerstwa Zdrowia Dotycząca Liczby Zakażonych Oraz Zgonów Pielęgniarek i Położnych z Powodu COVID-19 od Początku Pandemii. 2022. Available online: https://nipip.pl/informacja-ministerstwa-zdrowia-dotyczaca-liczby-zakazonych-oraz-zgonow-pielegniarek-i-poloznych-z-powodu-covid-19-od-poczatku-pandemii/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Taghinezhad, F.; Mohammadi, E.; Khademi, M. The role of the coronavirus pandemic on social attitudes towards the human aspects of the nursing profession. Iran J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2020, 25, 539. [Google Scholar]

- Zamanzadeh, V.; Purabdollah, M.; Ghasempour, M. Social acceptance of nursing during the coronavirus pandemic: COVID-19 an opportunity to reform the public image of nursing. Nurs. Open. 2022, 9, 2525–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.L.; James, A.H.; Kelly, D. Beyond tropes: Towards a new image of nursing in the wake of COVID-19. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa o Zawodach Pielęgniarki i Położnej. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19960910410/U/D19960410Lj.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Senat, R.P. Zawody Zaufania Publicznego, Zawody Regulowane Oraz Wolne Zawody. Geneza, Funkcjonowanie i Aktualne Problemy. Available online: http://paluchja-zajecia.home.amu.edu.pl/etyka/Zawody%20zaufania%20publicznego.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Stachoń, K.; Rybka, M. Pielęgniarstwo jako zawód zaufania publicznego w opinii pacjentów. Innow. Piel. Nauk. Zdr. 2016, 4, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bączyk-Rozwadowska, K. Samodzielność zawodowa pielęgniarki, położnej i ratownika medycznego. Stud. Iurid. Toruniensia 2019, 22, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2021_ae3016b9-en (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Naczelna Izba Pielęgniarek i Położnych. Raport. Katastrofa Kadrowa Pielęgniarek i Położnych—Raport Naczelnej Izby Pielęgniarek i Położnych. Available online: https://nipip.pl/raport2021/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Crisp, N.; Iro, E. Nursing Now campaign: Raising the status of nurses. Lancet 2018, 391, 920–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W.; Bakowska, G.; Kwiecień-Jaguś, K.; Gaworska-Krzemińska, A. Postrzeganie zawodu pielęgniarki przez młodzież szkół ponadgimnazjalnych jako wybór przyszłego zawodu—doniesienia wstępne. Probl. Pielęg. 2012, 20, 192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Siwek, M.; Nowak-Starz, G. Współczesny wizerunek pielęgniarstwa w opinii społeczeństwa. Piel. Pol. 2017, 3, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, E.; Wilson, T.D.; Akert, R.M. Social Psychology, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kluczyńska, U. (Nie)obecność mężczyzn w pielęgniarstwie—funkcjonujące stereotypy i ich konsekwencje. Now. Lekarskie. 2012, 81, 564–568. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S.; Peter, E.; Killackey, T.; Maciver, J. The “nurse as hero” discourse in the COVID-19 pandemic: A poststructural discourse analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 117, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej, A. Czynniki określające status społeczny pielęgniarek. Hygeia Public Health 2014, 49, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kluczyńska, U. Motives for choosing and resigning from nursing by men and the definition of masculinity: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralewicz, D.; Kuriata-Kościelniak, E.; Mróz, S. Opinia studentów pielęgniarstwa na temat wizerunku zawodowego pielęgniarek w Polsce. Piel. Zdr. Publ. 2017, 7, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvin, J.; Jackson, D.; Hutchinson, M. Contemporary public perceptions of nursing: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the international research evidence. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glerean, N.; Hupli, M.; Talman, K.; Haavisto, E. Young peoples’ perceptions of the nursing profession: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 57, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teresa-Morales, C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; Araujo-Hernández, M.; Feria-Ramírez, C. Current stereotypes associated with nursing and nursing professionals: An integrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glerean, N.; Hupli, M.; Talman, K.; Haavisto, E. Perception of nursing profession—Focus group interview among applicants to nursing education. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clow, K.A.; Ricciardelli, R.; Bartfay, W.J. Attitudes and stereotypes of male and female nurses: The influence of social roles and ambivalent sexism. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2014, 46, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, E.; Filar-Mierzwa, K. Prestiż wybranych zawodów medycznych w opinii reprezentantów tych zawodów. Med. Pr. 2019, 70, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Które Zawody Poważamy? 2019. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2019/K_157_19.PDF (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Radosz, Z.; Gniadek, A.; Kulik, H.; Paplaczyk, M. Social reception of nursing in selected countries of the European Union. Probl. Pielęg. 2021, 29, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, A.; Nowak–Starz, G. Subiektywna ocena pacjentów dotycząca postawy personelu medycznego podstawowej opieki zdrowotnej w świetle satysfakcji z usług medycznych. Piel. Pol. 2015, 3, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machul, M.; Chrzan-Rodak, A.; Bieniak, M.; Bąk, J.; Chadłaś-Majdańska, J.; Dobrowolska, B. Wizerunek pielęgniarek i pielęgniarstwa w Polsce w mediach oraz w opinii różnych grup społecznych. Systematyczny przegląd piśmiennictwa naukowego z lat 2010–2017. Piel. XXI Wieku. 2018, 1, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk, D.; Tobolska, B. Wizerunek zawodu pielęgniarki z perspektywy lekarzy, pacjentów i pielęgniarek. Med. Pr. 2011, 3, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Porth, C. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, S.; Ironside, P.; Spence, D.; Smythe, L. Crafting stories in hermeneutic, phenomenology research: A methodological device. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peat, G.; Rodriguez, A.; Smith, J. Interpretive phenomenological analysis applied to healthcare research. Evid. Based Nurs. 2019, 22, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, C. Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCosker, H.; Barnard, A.; Gerber, R. Undertaking sensitive research: Issues and strategies for meeting the safety needs of all participants. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2001, 2, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E.C. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldermann, S.K.; Hiebl, M.R. Using quotations from non-English interviews in accounting research. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2019, 17, 229–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Nistal, M.M.; Tortajada-Soler, M.; Rodriguez-Puente, Z.; Puente-Martínez, M.T.; Méndez-Martínez, C.; Fernández-Fernández, J.A. Patient perception of nursing care in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Enferm. Glob. 2021, 20, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Jung, S.; Park, H.; Lee, Y.; Son, Y. Perceptions related to nursing and nursing staff in long-term care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic era: Using social networking service. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fu, W.; Tian, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, B.; Mao, J.; Saligan, L.N. Professional identity of Chinese nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: A nation-wide cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 52, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, C.M. The social impact of COVID-19 as perceived by the employees of a UK mental health service. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalky, H.F.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Amarneh, B.H.; AlAzzam, R.N.M.; Yacoub, N.R.; Khalifeh, A.H.; Aldalaykeh, M.; Dalky, A.F.; Rawashdeh, R.A.; Yehia, D.B.; et al. Social discrimination perception of health-care workers and ordinary people toward individuals with COVID-19. Soc. Influ. 2020, 15, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Subedi, M. COVID-19 and stigma: Social discrimination towards frontline healthcare providers and COVID-19 recovered patients in Nepal. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 53, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzymski, P.; Mamzer, H.; Nowicki, M. The main sources and potential effects of COVID-19-related discrimination. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1318, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schubert, M.; Ludwig, J.; Freiberg, A.; Hahne, T.M.; Romero Starke, K.; Girbig, M.; Faller, G.; Apfelbacher, C.; von dem Knesebeck, O.; Seidler, A. Stigmatization from work-related COVID-19 exposure: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yufika, A.; Pratama, R.; Anwar, S.; Winardi, W.; Librianty, N.; Prashanti, N.A.P.; Sari, T.N.W.; Utomo, P.S.; Dwiamelia, T.; Natha, P.P.C.; et al. Stigma associated with COVID-19 among health care workers in Indonesia. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1942–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanini, R.; Visintini, E.; Rossettini, G.; Caruzzo, D.; Longhini, J.; Palese, A. Italian nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis of internet posts. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela Banai, I.; Banai, B.; Mikloušić, I. Beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories, compliance with the preventive measures, and trust in government medical officials. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 7448–7458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes-Parish, J.; Elliott, R.; Rolls, K.; Massey, D. Angels and Heroes: The Unintended Consequence of the Hero Narrative. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020, 52, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Cosentino, C.; Bettinaglio, G.C.; Giovanelli, F.; Prandi, C.; Pedrotti, P.; Preda, D.; D’Ercole, A.; Sarli, L.; Artioli, G. Nurse’s identity role during COVID-19. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021036. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes-Parish, J.; Massey, D.; Rolls, K.; Elliott, R. The angels and heroes of health care: Justified and appropriate, or harmful and destructive? J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 17, 847–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes-Parish, J.; Barrett, D.; Elliott, R.; Massey, D.; Rolls, K.; Credland, N. Fallen angels and forgotten heroes: A descriptive qualitative study exploring the impact of the angel and hero narrative on critical care nurses. Aust. Crit. Care. 2022, 36, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, J. ‘Heroes in healthcare; what’s wrong with that?’. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2020, 32, 567–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipworth, W. Beyond duty: Medical “heroes” and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bioeth. Inq. 2020, 17, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.L. ‘Healthcare Heroes’: Problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 46, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domaradzki, J. ‘Who else if not we’. Medical students’ perception and experiences with volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis in Poznan, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nes, F.; Abma, T.; Jonsson, H.; Deeg, D. Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? Eur. J. Ageing 2010, 7, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Gender | Age Range | Education | Specialisation | Seniority (in Years) | Hospital | Type of Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Female | 35–39 | Master’s | Surgical | 17 | Private | 60 h weeks |

| N2 | Male | 30–34 | Master’s | - | 5 | Public | 80 h weeks |

| N3 | Female | 25–29 | Master’s | - | 6 | Public | 40 h weeks |

| N4 | Female | 65–69 | Medical high school | - | 45 | Public | 40 h weeks |

| N5 | Female | 45–49 | PhD | Diabetes | 25 | Public | 20 h weeks |

| N6 | Female | 45–49 | Fedical high school | - | 27 | Public | 60 h weeks |

| N7 | Female | 55–59 | PhD | Oncology | 34 | Public | 40 h weeks |

| N8 | Female | 18–24 | Master’s | - | 2 | Public | 80 h weeks |

| N9 | Male | 55–59 | Master’s | Oncology | 34 | Public | 40 h weeks |

| N10 | Female | 50–54 | Bachelor’s | Conservative medicine | 31 | Public | 40 h weeks |

| N11 | Female | 55–59 | Medical high school | - | 37 | Public | 80 h weeks |

| N12 | Female | 45–49 | Master’s | Internal medicine | 22 | Public | 20 h weeks |

| N13 | Female | 45–49 | Bachelor’s | Diabetes | 22 | Public | 40 h weeks |

| N14 | Female | 18–24 | Master’s | - | 2 | Public | 80 h weeks |

| N15 | Female | 18–24 | Master’s | - | 3 | Public | 80 h weeks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wałowska, K.; Domaradzki, J. Superheroes or Super Spreaders? The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Attitudes towards Nurses: A Qualitative Study from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042912

Wałowska K, Domaradzki J. Superheroes or Super Spreaders? The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Attitudes towards Nurses: A Qualitative Study from Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042912

Chicago/Turabian StyleWałowska, Katarzyna, and Jan Domaradzki. 2023. "Superheroes or Super Spreaders? The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Attitudes towards Nurses: A Qualitative Study from Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042912

APA StyleWałowska, K., & Domaradzki, J. (2023). Superheroes or Super Spreaders? The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Attitudes towards Nurses: A Qualitative Study from Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042912