Nursing Interventions against Bullying: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

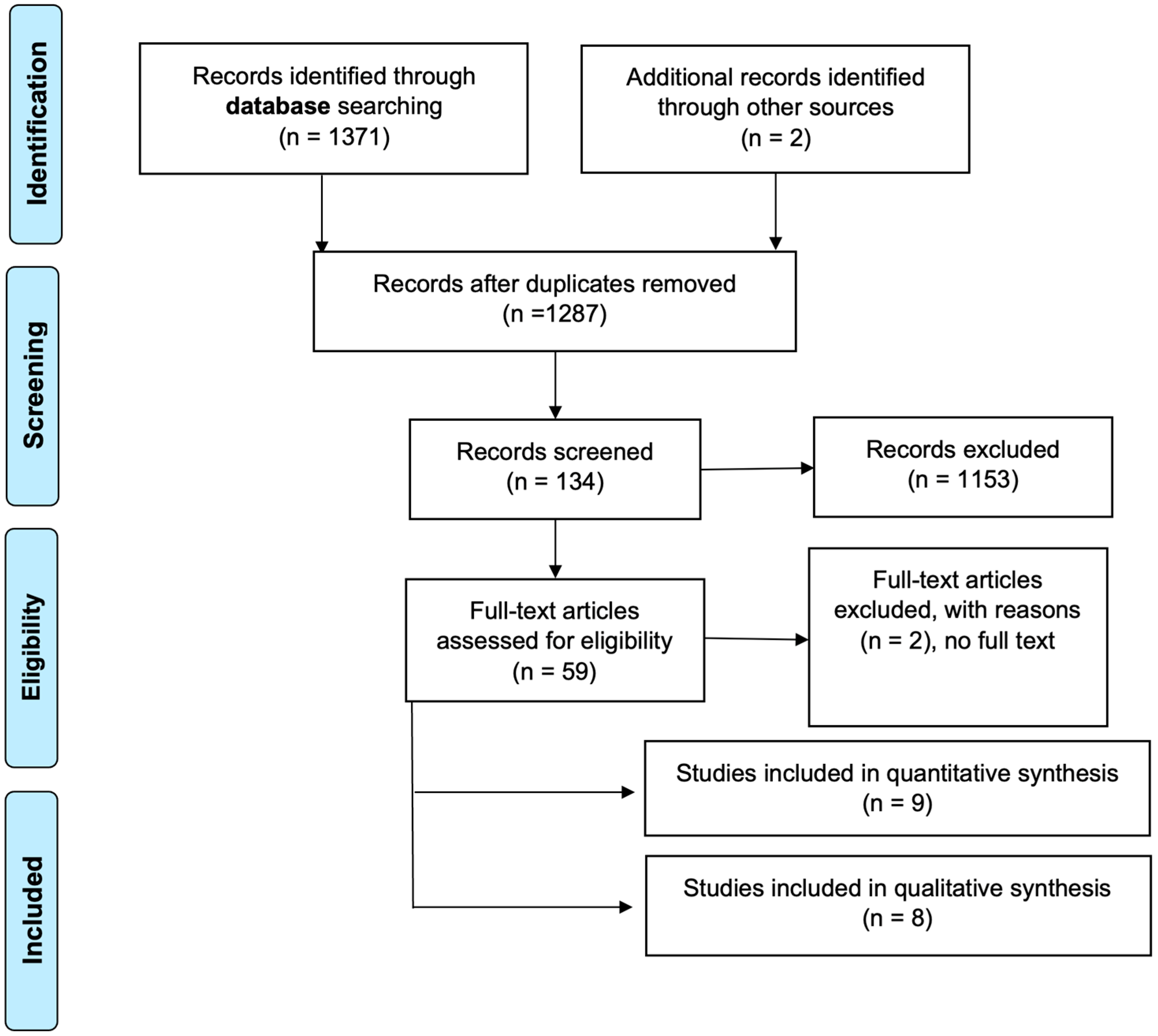

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Risk of Bias Analysis

2.5. Tabulation and Data Analysis

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Summary of Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Primary Prevention: Awareness Raising

4.2. Secondary Prevention: Coping Mechanisms

4.3. Tertiary Prevention: Approach/Care

4.4. Nursing Skills in Dealing with Bullying

4.5. Role of the Family in Dealing with Bullying

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kvarme, L.G.; Misvær, N.; Valla, L.; Myhre, M.C.; Holen, S.; Sagatun, Å. Bullying in School: Importance of and Challenges Involved in Talking to the School Nurse. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020, 36, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evgin, D.; Bayat, M. Department of Pediatrics Nursing, Erciyes University Faculty of Health Sciences, Kayseri, Turkey. The Effect of Behavioral System Model Based Nursing Intervention on Adolescent Bullying. Florence Nightingale J. Nurs. 2020, 28, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.L.d.; Oliveira, W.A.d.; Carlos, D.M.; Lizzi, E.A.d.S.; Rosário, R.; Silva, M.A.I. Intervention in Social Skills and Bullying. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão Neto, W.; Silva, C.O.d.; Amorim, R.R.T.d.; Aquino, J.M.d.; Almeida Filho, A.J.d.; Gomes, B.d.M.R.; Monteiro, E.M.L.M. Formation of Protagonist Adolescents to Prevent Bullying in School Contexts. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73 (Suppl 1), e20190418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Grunin, L.; Guetterman, T. School Nurses’ Perspectives of Bullying Involvement of Adolescents with Chronic Health Conditions. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2022, 9, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencastro, L.C.d.S.; Silva, J.L.d.; Komatsu, A.V.; Bernardino, F.B.S.; Mello, F.C.M.d.; Silva, M.A.I. Theater of the Oppressed and Bullying: Nursing Performance in School Adolescent Health. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20170910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk Çopur, E.; Kubilay, G. The Effect of Solution-focused Approaches on Adolescents’ Peer Bullying Skills: A Quasi-experimental Study. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 35, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, E.; Melnyk, B.; Hensley, V.; Sinnott, L.T. Childhood Bullying: Screening and Intervening Practices of Pediatric Primary Care Providers. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2019, 33, e39–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, L.D.P.d.; Torres, R.A.M.; Veras, K.d.C.B.B.; Araújo, A.F.d.; Costa, I.G.; Oliveira, G.R. Web Radio: Educational nursing care technology addressing cyberbullying students’ statements. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20180872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Sánchez, I.; Gómez Vallejo, E.I.; Goig Martínez, R. El acoso escolar en educación secundaria: Prevalencia y abordaje a través de un estudio de caso. Comunitania Rev. Int. Trab. Soc. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, A.J.; Valla, L.; Albertini Früh, E.; Kvarme, L.G. A Path to Inclusiveness—Peer Support Groups as a Resource for Change. J. Sch. Nurs. 2022, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cabrera, J.; Machimbarrena, J.M.; Ortega-Barón, J.; Álvarez-Bardón, A. Joint Association of Bullying and Cyberbullying in Health-Related Quality of Life in a Sample of Adolescents. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo General de Enfermería de España. Código Deontológico de La Enfermería Española. 1989. Available online: https://www.consejogeneralenfermeria.org/component/jdownloads/send/128-etica-y-deontologia/2313-codigo-deontologico-de-la-enfermeria-espanola (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Kub, J.; Feldman, M.A. Bullying prevention: A call for collaborative efforts between school nurses and school psychologists: Bullying Prevention. Psychol. Sch. 2015, 52, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Santos, A.-E.; Tizón Bouza, E.; Fernández-Morante, C.; Casal Otero, L.; Cebreiro, B. La Enfermería escolar: Contenidos y percepciones sobre su pertinencia en las escuelas inclusivas. Enferm. Glob. 2019, 18, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una Propuesta Para Mejorar La Publicación de Revisiones Sistemáticas y Metaanálisis. Med. Clínica 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies: A Typology of Reviews. Maria J. Grant Andrew Booth. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Asenjo-Lobos, C.; Otzen, T. Jerarquización de la evidencia: Niveles de evidencia y grados de recomendación de uso actual. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2014, 31, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Romero, H.R.; Norella Córdoba, D.; López, M.J.; Villarraga, D.; Ayala, J.; Pinzón, J.; Rodríguez, L.; Mondragón, E.C. Conocimiento de los niños, niñas y adolescentes del acoso escolar en una institución educativa de la localidad de Ciudad Bolívar (Colombia). Un aporte desde enfermería para la reconciliación y reconstrucción de la paz. Horiz. Enfermeria 2021, 32, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Menino, D.D.; Sava, L.M.; Perrotti, J.; Barnes, T.N.; Humphrey, D.L.; Reisner, S.L. LGBTQ Bullying: A Qualitative Investigation of Student and School Health Professional Perspectives. J. LGBT Youth 2020, 17, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soimah; Hamid, A.Y.S.; Daulima, N.H.C. Family’s Support for Adolescent Victims of Bullying. Enferm. Clínica 2019, 29, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsar, F.; Ayaz Alkaya, S. Turkish Validity and Reliability Study of the Student-Advocates Pre- and Post-Scale. J. Educ. Res. Nurs. 2022, 18, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, R.A.; Flatø, M.; Bru, L.E.; Midthassel, U.V.; Helleve, A.; Rønsen, E. Can School Nurses Improve the School Environment in Norwegian Primary Schools? A Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 96, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, H.; Ozturk, C. Examining the Effect of a Program Developed to Address Bullying in Primary Schools. J. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 7, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burk, J.; Park, M.; Saewyc, E. A Media-Based School Intervention to Reduce Sexual Orientation Prejudice and Its Relationship to Discrimination, Bullying, and the Mental Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents in Western Canada: A Population-Based Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, E.; Vessey, J.A.; Pfeifer, L. Cyberbullying and Social Media: Information and Interventions for School Nurses Working With Victims, Students, and Families. J. Sch. Nurs. 2018, 34, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNike, M.; Gordon, H. Solution Team: Outcomes of a Target-Centered Approach to Resolving School Bullying. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 24, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, D.; Özgür, G. Effect of a Solution-Focused Approach on Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem in Turkish Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2019, 57, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedjat-Haiem, F.R.; Cadet, T.J.; Amatya, A.; Mishra, S.I. Healthcare Providers’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Practice Behaviors for Educating Patients About Advance Directives: A National Survey. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2019, 36, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.M.; Hamdan, K.M.; Albqoor, M.; Othman, A.K.; Amre, H.M.; Hazeem, M.N.A. Perceived Social Support from Family and Friends and Bullying Victimization among Adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 107, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosep, I.; Hikmat, R.; Mardhiyah, A. School-Based Nursing Interventions for Preventing Bullying and Reducing Its Incidence on Students: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosep, I.; Hikmat, R.; Mardhiyah, A.; Hazmi, H.; Hernawaty, T. Method of Nursing Interventions to Reduce the Incidence of Bullying and Its Impact on Students in School: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authorship/Year/Country | Target Group/Performed by/Duration | Procedure/Outcome/Type of Intervention | SIGN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brandão-Neto W et al. (2020), Brazil [4] | Students aged 13–16 Researchers (nurses) in collaboration with teaching staff 1 year (June 2017–May 2018) | Anti-bullying Health Education Programme (PATES). Selection/training of influential pupils with high social status, leadership, and conflict resolution skills. Culture circles, with themes:

- Primary Prevention: Awareness raising | 3 |

| Abreu LDP et al. (2020), Brazil [9] | Young people aged 14–15 Researchers (nurses), teaching staff, a nurse specialist, and radio personnel 1 h | Web radio “In Tune with Health” programme, interview with a nurse specialising in cyberbullying. Discussion based on the anchor question “What do you understand by cyberbullying?”, via social media, the radio programme’s web board, Whatsapp, and Facebook, leading to:

| 3 |

| Alvarado Romero HR et al. (2021), Colombia [19] | Adolescents aged 12–17 Researchers (nurses) Not specified | Analysis of participants’ knowledge of bullying via a survey and focus group discussion. Results:

| 3 |

| Heitmann AJ, Valla L, Kvarme LG, (2022), Norway [11] | Young people aged 11–13 Researchers (nurses), school nurses and teachers 4 months (January–April 2021) | Support groups (60 min) for victims of bullying based on the solution-focused approach. Three teachers and one school nurse received four days of training in group management and solution-focused approach techniques. The groups and interviews were structured using ad hoc guides. Results: Following the intervention, 40-min interviews were conducted with four participants who had experienced bullying. In addition, weekly 30 min follow-up sessions were held in which they expressed how effective their participation in the support groups had been in coping with their bullying situation. There was some improvement among bullying victims. - Tertiary Prevention: Approach/Care | 3 |

| Kvarme LG, Misvaer N, Valla L, Myhre MC, Holen S. (2019) Norway [1] | Students aged 13–14 Researchers (nurses) and 4 school nurses 1 month (December 2017) | Pilot project “School Health” which included a web-based questionnaire completed before a consultation with the school nurse, who, after analysing the information from the questionnaires, decided who would take part in the individual interviews and focus groups. A guide was available for both processes. Results:

| 3 |

| Cohen SS, Grunin L, Guetterman TC. (2022) USA [5] | School nurses Researchers (nurses) 10 months (January–October 2019) | 45 min telephone interviews with school nurses about their role in dealing with bullying. Results:

| 3 |

| Earnshaw VA et al. (2021) USA [20] | Students aged 13–24 and school nurses Researchers (nurses) Not specified | Five online asynchronous focus groups were held to find out how nurses engage with and perceive the detection and management of bullying of LGBTQ students, compared to the experience of LGBTQ students. Rapid qualitative inquiry methodology was followed. Results: There is a disconnect between students’ perceptions of LGBTQ bullying and those of school nurses. - Nursing skills in dealing with bullying | |

| Soimah AYS, Hamidÿ NCD (2019) Indonesia [21] | Parents of bullying victims, aged 38–56 Researchers (nurses) 6 months (January–June 2017) | Personal interviews at the participants’ homes, with data obtained using the Colaizzi method. Results:

| 3 |

| Authorship/Year/Country | Target Group/Performed by/Duration | Procedure/Outcome/Type of Intervention | SIGN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avşar F, Alkaya S, (2019), Turkey [22] | Children aged 10–11 Researchers (nurses) Not specified | Validation of the Student-Advocates scale, which is based on four useful strategies to support bystanders in bullying situations. Results:

| 2++ |

| Alencastro LCS et al. (2020), Brazil [6] | Pupils aged 15–16 Researchers (nurses) 2 months (October–November 2016) | Anti-bullying intervention based on the “Theatre of the Oppressed”, divided into 16 sessions, 4 team meetings, 10 rehearsals, and 2 theatre performances. Results: Comparison of the difference in victimisation in the intervention group (IG) and control group (CG). In the IG, there was a reduction in the incidence of any of the types of aggression, compared to the CG. - Primary Prevention: Awareness raising | 2++ |

| Öztürk Çopur E, Kubilay G, (2021) Turkey [7] | Adolescents aged 13–14 Researchers (nurses) 6 weeks | This applies the solution-focused approach as a method of social skills training for dealing with bullying, with its impact being measured using the Personal Information Form and the Adolescent Peer Relationship Instrument (APRI) scale, with weekly 50 min sessions around themes:

- Secondary Prevention: Coping mechanisms | 2+ |

| Federici RA et al. (2020) Norway [23] | School nurses, school principals, and the municipal authority Researchers (teachers and psychiatrists) 5 years: 3 interventions, 2 follow-ups | Increase the presence of school nurses by 50%, to six and a half hours (three and a quarter hours for student care and three and a quarter hours for administrative and training tasks) in 5th, 6th, and 7th grades, reducing ratios (maximum two students per nurse) and attending to the students’ psychosocial environment, in order to reduce bullying. Beforehand, the researchers organised a two-day briefing session for the school health service, school nurses, school headteachers, and the municipal authority. Expected results: improvement in the psychosocial environment and academic results. - Nursing skills in dealing with bullying | 1+ |

| Karataş H, Öztürk C (2019) Turkey [24] | 113 pupils and 26 parents Researchers (nurses) 1 year 7 weeks | Three-tiered anti-bullying training:

- Secondary Prevention: Coping mechanisms | 2+ |

| Evgin, D., Bayat, M, (2020) Turkey [2] | Adolescents aged 12–14 Researchers (nurses) 5 months (May–September 2014) | Three-stage nursing care process, adopting Johnson’s Behavioural System educational model:

- Secondary Prevention: Coping mechanisms | 2+ |

| Silva JL et al. (2018), Brazil [3] | Students with an average age of 11.2 years 4 months (March–June 2015) | Social skills training over eight weekly 50 min sessions, based on cognitive-behavioural techniques: role-playing, dramatizations, positive reinforcement, modelling, feedback, videos, and homework. Sessions were structured into three sections: 1: explanation of the task, 2: performance of the task, 3: feedback on the task. Included content and activities on good manners, making friends, empathy, self-control, emotional expressiveness, assertiveness, and interpersonal problem solving. Results: a reduction in victimisation was observed in the intervention group. - Tertiary Prevention: Approach/Care | 2− |

| Hutson E, Melnyk B, Hensley V, Sinnott LT, (2019) USA [8] | Paediatric primary care nurses Researchers (nurses) 1 month (May 2017) | Description of paediatric primary care nurses’ practices, knowledge, and attitudes using the modified Health Care Provider’s Practices, Attitudes, Self-Confidence and Knowledge Regarding Bullying (HCP-PACK) questionnaire. Results:

| 2++ |

| Burk J, Park M, Saewyc EM. (2018), Canada [25] | Adolescents aged 13–18 Researchers (nurses) 6 months (January–June 2013) | “Out in Schools” programme of short films featuring different sexual orientations, aiming to reduce homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia, leading to a lower rate of bullying and suicidal tendencies and an increase in support from the school environment. Sessions of one–two hours. Data were acquired from the British Columbia Adolescent Health Survey (BCAHS). Results: programme linked to an improvement in the well-being of LGBTQ students. - Primary Prevention: Awareness raising | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Celdrán-Navarro, M.d.C.; Leal-Costa, C.; Suárez-Cortés, M.; Molina-Rodríguez, A.; Jiménez-Ruiz, I. Nursing Interventions against Bullying: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042914

Celdrán-Navarro MdC, Leal-Costa C, Suárez-Cortés M, Molina-Rodríguez A, Jiménez-Ruiz I. Nursing Interventions against Bullying: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042914

Chicago/Turabian StyleCeldrán-Navarro, María del Carmen, César Leal-Costa, María Suárez-Cortés, Alonso Molina-Rodríguez, and Ismael Jiménez-Ruiz. 2023. "Nursing Interventions against Bullying: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042914

APA StyleCeldrán-Navarro, M. d. C., Leal-Costa, C., Suárez-Cortés, M., Molina-Rodríguez, A., & Jiménez-Ruiz, I. (2023). Nursing Interventions against Bullying: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042914