A Structural Validation of the Brief COPE Scale among Outpatients with Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Citation | Country | N and Sample | Type of Analysis | Factorial Structure, and Items/Subscales Removed a Priori |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Richard’s and et al., 2021) [20] | Argentina | 504 elderly | EFA/CFA | 02 factor model |

| (Tang et al., 2021) [21] | China | 217 caregivers, cared for children with chronic illnesses | EFA | 03 factor model |

| (Power et al., 2021) [22] | Canada | 377 federally incarcerated inmates | PCA/CFA | 08 factor model 5 items excluded |

| (Mackay et al, 2021) [23] | Canada | 174 melanoma patients | EFA | 08 factor model |

| (Azale et al., 2018) [24] | Ethiopia | 385 women with symptoms of postpartum depression | CFA | 03 factor model |

| (Muller et al., 2003) [25] | France | 3846 French adults | CFA | 14 factor model |

| (Radat et al., 2009) [26] | France | 1534 adult migraine sufferers | PCA | 06 factor model |

| (Doron et al., 2014) [27] | France | 2771 university students | CFA | 05 factor model |

| (Baumstarck and et al., 2017) [28] | France | 398 cancer patients and their caregivers | PCA/CFA | 04 factor model |

| (Pozzi et al., 2015) [29] | Italy | 148 adults with an anxiety disorder | PCA | 09 factor model |

| (Nunes et al., 2021) [30] | Portugal | 269 at-risk parents. | CFA | 14 factor model |

| (Alghamdi, M., 2020) [31] | Saudi Arabia | 302 adults | PCA | 03 factor model |

| (Peters et al., 2020) [32] | USA | 189 pregnant women | CFA | 13 factor model Exclusions of substance use items |

| (Cramer et al., 2020) [33] | USA | 576 college students | CFA | 04 factor model Self-blame and self-distraction removed |

| (Abdul Rahman et al., 2021) [34] | United Arab Emirates | 423 female nurses | CFA/EFA | 02 factor model Exclusions of 06 items (1, 4, 11, 18, 19, and 28) |

| (Matsumoto et al., 2020) [35] | Vietnam | 1164 HIV-infected patients | CFA/EFA | 06 factor model Two items removed on EFA |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Coping Strategies

2.2.2. Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.3.2. Construct Validity

2.3.3. Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Sample

3.2. Factorial Analysis

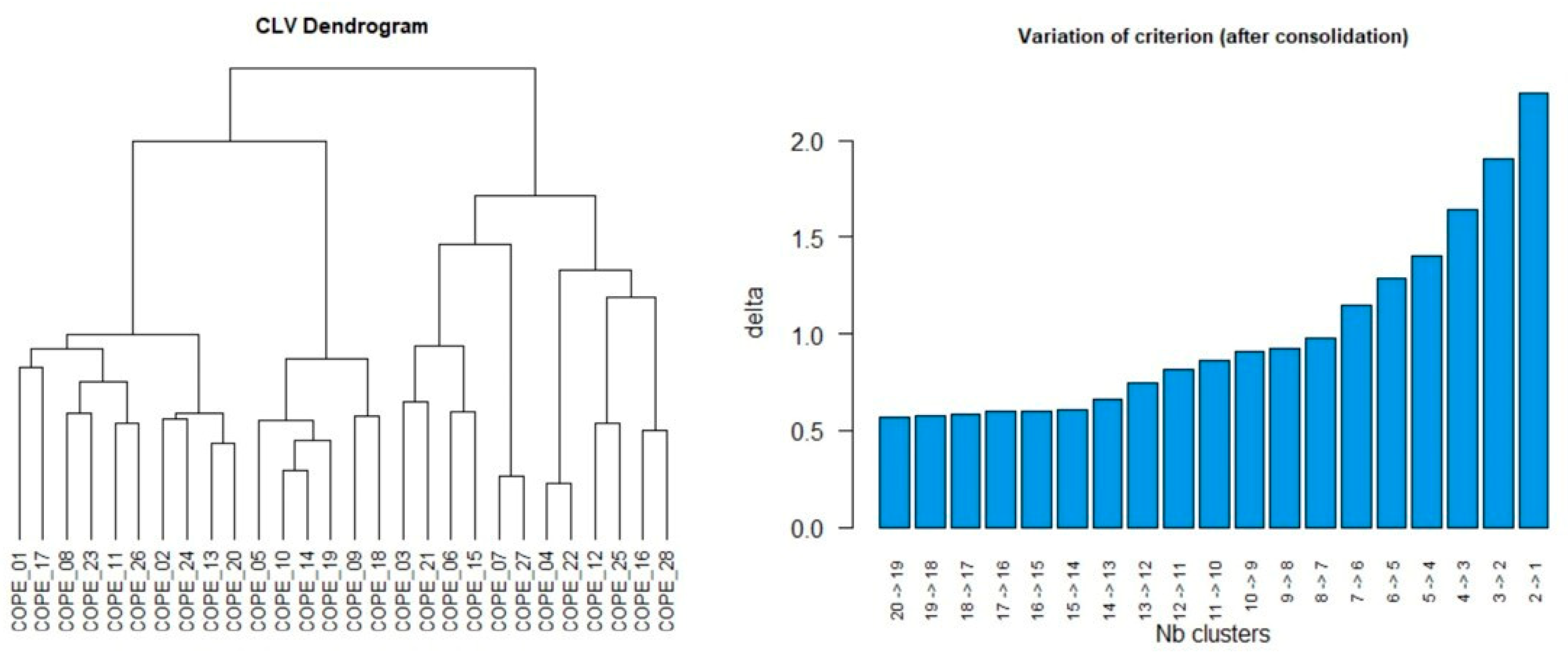

3.2.1. Clustering around Latent Variable

3.2.2. Selection of Fit Models: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2.3. Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLV | Clustering Analysis on Latent Variables |

| SUDs | Substance Use Disorders |

| FC | Factor Complexity |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| PCA | Principal Components Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| SAS | Statistical Analysis System |

Appendix A

| I Haven’t Been Doing This at All | A Little Bit | A Medium Amount | I’ve Been Doing This a Lot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

| I Haven’t Been Doing This at All | A Little Bit | A Medium Amount | I’ve Been Doing This a Lot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

General Rules for Use

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Blithikioti, C.; Nuño, L.; Paniello, B.; Gual, A.; Miquel, L. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on individuals under treatment for substance use disorders: Risk factors for adverse mental health outcomes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 139, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Janmohamed, K.; Nyhan, K.; Martins, S.S.; Cerda, M.; Hasin, D.; Scott, J.; Pates, R.; Ghandour, L.; Wazaify, M.; et al. Substance use and substance use disorder, in relation to COVID-19: Protocol for a scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinotti, G.; Alessi, M.C.; Di Natale, C.; Sociali, A.; Ceci, F.; Lucidi, L.; Picutti, E.; Di Carlo, F.; Corbo, M.; Vellante, F.; et al. Psychopathological Burden and Quality of Life in Substance Users During the COVID-19 Lockdown Period in Italy. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 572245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Rogers, J.; Mason, R.; Siriwardena, A.N.; Hogue, T.; Whitley, G.A.; Law, G.R. Alcohol and other substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 229 Pt A, 109150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.-G.P.; Stringfellow, E.J.; DiGennaro, C.; Poellinger, N.; Wood, J.; Wakeman, S.; Jalali, M.S. Opioid overdose decedent characteristics during COVID-19. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeyre-Mestre, M.; Boucher, A.; Daveluy, A.; Gibaja, V.; Jouanjus, E.; Mallaret, M.; Peyrière, H.; Micallef, J. French Addictovigilance Network. Addictovigilance contribution during COVID-19 epidemic and lockdown in France. Therapies 2020, 75, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, B. Supplying synthetic opioids during a pandemic: An early look at North America. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 93, 102833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Products-Vital Statistics Rapid Release-Provisional Drug Overdose Data. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Flaudias, V.; Zerhouni, O.; Pereira, B.; Cherpitel, C.J.; Boudesseul, J.; de Chazeron, I.; Romo, L.; Guillaume, S.; Samalin, L.; Cabe, J.; et al. The Early Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Stress and Addictive Behaviors in an Alcohol-Consuming Student Population in France. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 628631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabelo-Roche, J.R.; Iglesias-Moré, S.; Gómez-García, A.M. Persons with Substance Abuse Disorders and Other Addictions: Coping with the COVID-19 Pandemic. MEDICC Rev. 2021, 23, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. The Role of Coping in the Emotions and How Coping Changes over the Life Course. In Handbook of Emotion, Adult Development, and Aging; Magai, C., McFadden, S.H., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996; Chapter 16; pp. 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, A.; Antúnez, J.M.; Navarro, J.F. Coping strategies related to treatment in substance use disorder patients with and without comorbid depression. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 251, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, M.D.; Kadden, R.M.; Tennen, H. The nature of coping in treatment for marijuana dependence: Latent structure and validation of the Coping Strategies Scale. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012, 26, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, M.A.; Gridley, M.K.; Peters, R.M. The Factor Structure of the Brief Cope: A Systematic Review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 44, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Lara, S.A. Exploratory factorial analysis and factorial complexity: Beyond rotations. Enferm. Clin. 2016, 26, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H.W.; Morin, A.J.; Parker, P.D.; Kaur, G. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling: An Integration of the Best Features of Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard’S, M.M.; Krzemien, D.; Comesaña, A.; Zamora, E.V.; Cupani, M. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Spanish version of the brief-COPE in Argentine elderly people. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 41, 8550–8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.P.Y.; Chan, C.W.; Choi, K. Factor Structure of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory in Chinese (Brief-COPE-C) in Caregivers of Children with Chronic Illnesses. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 59, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.; Smith, H.; Brown, S.L. The brief COPE: A factorial structure for incarcerated adults. Crim. Justice Stud. 2021, 34, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, S.; Burdayron, R.; Körner, A. Factor structure of the Brief COPE in patients with melanoma. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2021, 53, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azale, T.; Fekadu, A.; Medhin, G.; Hanlon, C. Coping strategies of women with postpartum depression symptoms in rural Ethiopia: A cross-sectional community study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, L.; Spitz, E. Multidimensional assessment of coping: Validation of the Brief COPE among French population. Encephale 2003, 29, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radat, F.; Lanteri-Minet, M.; Nachit-Ouinekh, F.; Massiou, H.; Lucas, C.; Pradalier, A.; Mercier, F.; El Hasnaoui, A. The GRIM2005 Study of Migraine Consultation in France. III: Psychological Features of Subjects with Migraine. Cephalalgia 2009, 29, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, J.; Trouillet, R.; Gana, K.; Boiché, J.; Neveu, R.; Ninot, G. Examination of the Hierarchical Structure of the Brief COPE in a French Sample: Empirical and Theoretical Convergences. J. Pers. Assess. 2014, 96, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumstarck, K.; Alessandrini, M.; Hamidou, Z.; Auquier, P.; Leroy, T.; Boyer, L. Assessment of coping: A new french four-factor structure of the brief COPE inventory. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, G.; Frustaci, A.; Tedeschi, D.; Solaroli, S.; Grandinetti, P.; Di Nicola, M.; Janiri, L. Coping strategies in a sample of anxiety patients: Factorial analysis and associations with psychopathology. Brain Behav. 2015, 5, e00351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Pérez-Padilla, J.; Martins, C.; Pechorro, P.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Ferreira, L. The Brief COPE: Measurement Invariance and Psychometric Properties among Community and At-Risk Portuguese Parents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, M. Cross-Cultural Validation and Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Brief COPE in Saudi Population. Med. J. Malaysia 2020, 75, 502–509. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, R.M.; Solberg, M.A.; Templin, T.N.; Cassidy-Bushrow, A.E. Psychometric Properties of the Brief COPE Among Pregnant African American Women. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 42, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, R.J.; Braitman, A.; Bryson, C.N.; Long, M.M.; La Guardia, A.C. The Brief COPE: Factor Structure and Associations With Self- and Other-Directed Aggression Among Emerging Adults. Eval. Health Prof. 2020, 43, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, H.; Issa, W.B.; Naing, L. Psychometric properties of brief-COPE inventory among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S.; Yamaoka, K.; Nguyen, H.D.T.; Nguyen, D.T.; Nagai, M.; Tanuma, J.; Mizushima, D.; Van Nguyen, K.; Pham, T.N.; Oka, S. Validation of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problem Experienced (Brief COPE) inventory in people living with HIV/AIDS in Vietnam. Glob. Health Med. 2020, 2, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2000; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigneau, E.; Chen, M.; Qannari, E.M. ClustVarLV: An R Package for the Clustering of Variables Around Latent Variables. R J. 2015, 7, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E. Neither Cronbach’s Alpha nor McDonald’s Omega: A Commentary on Sijtsma and Pfadt. Psychometrika 2021, 86, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Full Sample 1 | Alcohol-Dependent Outpatients 1 | Opioid-Dependent Outpatients 1 | p Value 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (n = 318) | (n = 157) | (n = 161) | ||

| Age | 38.4 (10.5) | 42.0 (12.3) | 34.7 (8) | <10−3 ** | |

| Gender | 0.61 | ||||

| Male | 78 | 78 | 78 | ||

| Female | 22 | 22 | 22 | ||

| Marital status | 0.002 * | ||||

| Never married | 47 | 39 | 55 | ||

| Married/living with a partner | 34 | 34 | 34 | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 19 | 27 | 11 | ||

| Educational level | <10−3 ** | ||||

| Primary school | 02 | 04 | 02 | ||

| Middle/High school | 73 | 59 | 86 | ||

| University | 25 | 37 | 12 | ||

| Living arrangements | <10−3 ** | ||||

| Alone | 78 | 46 | 62 | ||

| With family | 5.1 | 12 | 8.8 | ||

| With friends | 11 | 25 | 18 | ||

| Homeless | 5.9 | 17 | 11.2 | ||

| Occupational status | 0.01 * | ||||

| Full-time work | 56 | 64 | 48 | ||

| Part-time work | 24 | 18 | 30 | ||

| Unemployed/student | 17 | 15 | 20 | ||

| Retired | 03 | 03 | 02 | ||

| Duration of addiction (years) | 14.68 (10.4) | 20.42 (11.87) | 10.14 (7.11) | <10−3 ** | |

| Dimensions | Items | χ2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 14 | 28 | 433.532 ** | 0.938 | 0.909 | 0.044 | 0.046 | 24,076.722 | 24,986.930 |

| Model 2 | 07 | 28 | 715.074 ** | 0.862 | 0.841 | 0.058 | 0.069 | 24,218.264 | 24,515.982 |

| Model 3 | 09 | 28 | 599.150 ** | 0.898 | 0.877 | 0.051 | 0.060 | 24,132.340 | 24,488.055 |

| Model 4 | 09 | 24 | 300.922 ** | 0.962 | 0.950 | 0.034 | 0.042 | 20,931.234 | 21,273.211 |

| Items | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12. I’ve been trying to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 24. I’ve been learning to live with it. | 0.72 | ||||||||

| 17. I’ve been looking for something good in what is happening. | 0.86 | ||||||||

| 1. I’ve been turning to work or other activities to take my mind off things. | 0.49 | ||||||||

| 2. I’ve been concentrating my efforts on doing something about the situation I’m in. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 25. I’ve been thinking hard about what steps to take. | 0.86 | ||||||||

| 7. I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better. | 0.84 | ||||||||

| 14. I’ve been trying to come up with a strategy about what to do. | 0.94 | ||||||||

| 8. I’ve been refusing to believe that it has happened. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. I’ve been saying to myself “this isn’t real”. | 0.91 | ||||||||

| 11. I’ve been using alcohol or other drugs to help me get through it. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4. I’ve been using alcohol or other drugs to make myself feel better. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 10. I’ve been getting help and advice from other people. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 23. I’ve been trying to get advice or help from other people about what to do. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 15. I’ve been getting comfort and understanding from someone. | 0.94 | ||||||||

| 21. I’ve been expressing my negative feelings. | 0.50 | ||||||||

| 16. I’ve been giving up the attempt to cope. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6. I’ve been giving up trying to deal with it. | 0.79 | ||||||||

| 22. I’ve been trying to find comfort in my religion or spiritual beliefs. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 27. I’ve been praying or meditating. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 26. I’ve been blaming myself for things that happened. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 13. I’ve been criticizing myself. | 0.92 | ||||||||

| 18. I’ve been making jokes about it. | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 28. I’ve been making fun of the situation. | 0.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kadi, M.; Bourion-Bédès, S.; Bisch, M.; Baumann, C. A Structural Validation of the Brief COPE Scale among Outpatients with Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032695

Kadi M, Bourion-Bédès S, Bisch M, Baumann C. A Structural Validation of the Brief COPE Scale among Outpatients with Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032695

Chicago/Turabian StyleKadi, Melissa, Stéphanie Bourion-Bédès, Michael Bisch, and Cédric Baumann. 2023. "A Structural Validation of the Brief COPE Scale among Outpatients with Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032695

APA StyleKadi, M., Bourion-Bédès, S., Bisch, M., & Baumann, C. (2023). A Structural Validation of the Brief COPE Scale among Outpatients with Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032695