Are College Students Interested in Family Health History Education? A Large Needs Assessment Survey Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Instrument

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Interest in Receiving FHH Education

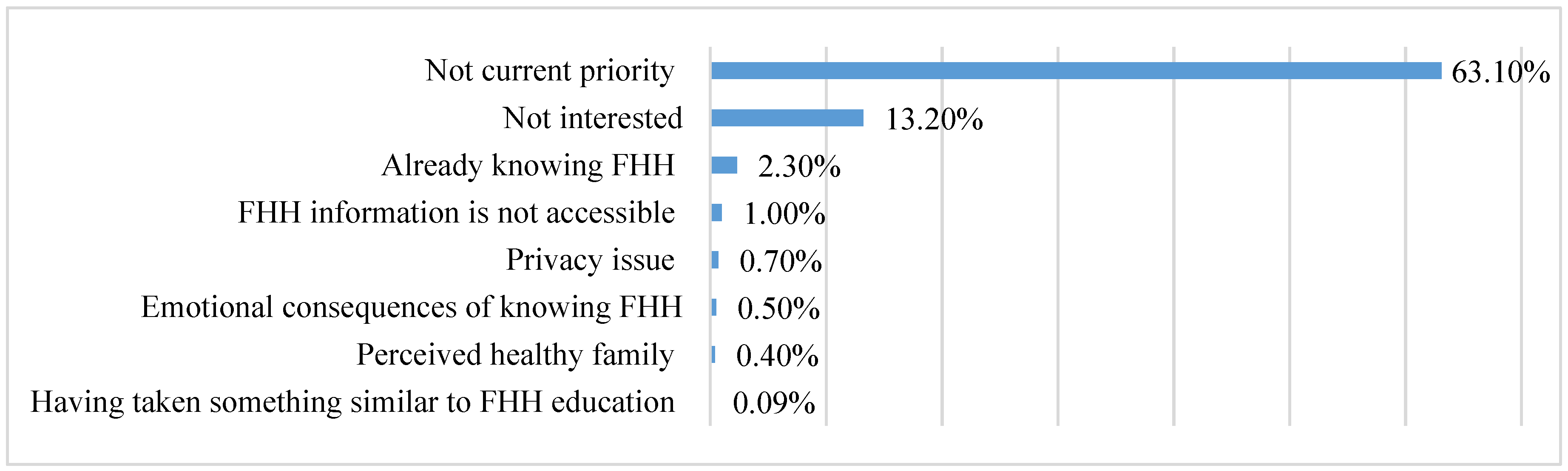

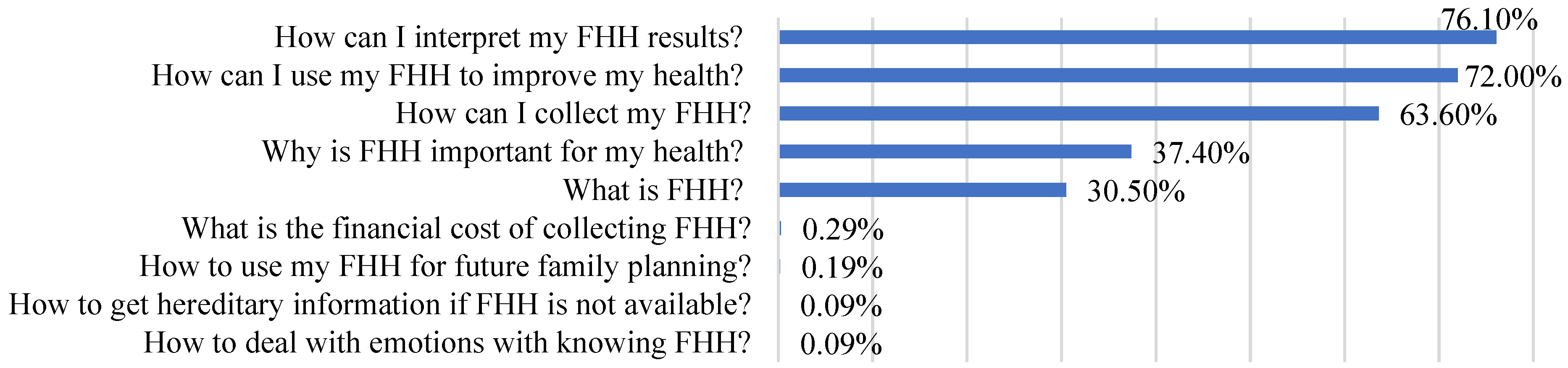

3.3. Desired FHH Educational Topics

3.4. Preferred FHH Educational Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valdez, R.; Yoon, P.W.; Qureshi, N.; Green, R.F.; Khoury, M.J. Family history in public health practice: A genomic tool for disease prevention and health promotion. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, V.C.; Orlando, L.A. Family health history: An essential starting point for personalized risk assessment and disease prevention. Pers. Med. 2016, 13, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttmacher, A.E.; Collins, F.S.; Carmona, R.H. The family history—more important than ever. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2333–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C.; Carthron, D.L.; Duren-Winfield, V.; Lawrence, W. An experiential cardiovascular health education program for African American college students. ABNF J. 2014, 25, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Giles, R.T.; Larsen, L.; Ware, J.; Adams, T.; Hunt, S.C. Utah’s family high risk program: Bridging the gap between genomics and public health. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2005, 2, A24. [Google Scholar]

- Butty, J.-A.M.; Richardson, F.; Mouton, C.P.; Royal, C.D.M.; Green, R.D.; Munroe, K.-A. Evaluation findings from genetics and family health history community-based workshops for African Americans. J. Community Genet. 2012, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.J.; Gratzer, W.; Lieber, C.; Edelson, V.; O’Leary, J.; Terry, S.F. Iona college community centered family health history project: Lessons learned from student focus groups. J. Genet. Couns. 2012, 21, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd-Martin, G.; Martinez, M.C.; Rayens, M.K.; Gokun, Y.; Meininger, J.C. Sociocultural tailoring of a healthy lifestyle intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes risk among Latinos. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, E200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijl, M.; Timmermans, D.R.; Claassen, L.; Janssens, A.C.J.; Nijpels, G.; Dekker, J.M.; Marteau, T.M.; Henneman, L. Impact of communicating familial risk of diabetes on illness perceptions and self-reported behavioral outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffin, M.T.; Nease, D.E.J.; Sen, A.; Pace, W.D.; Wang, C.; Acheson, L.S.; Rubinstein, W.S.; O’Neill, S.; Gramling, R.U.; Family Healthware Impact Trial Group. Effect of preventive messages tailored to family history on health behaviors: The Family Healthware Impact Trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2011, 9, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, S.; Young, C.M.; Foster, M.; Wang, J.H.-Y.; Tseng, T.-S.; Kwok, O.-M.; Chen, L.-S. Family health history–based interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Li, M.; Ma, P.; Kwok, O.-M.; Chen, L.-S. Effects of family health history-based colorectal cancer prevention education among non-adherent Chinese Americans to colorectal cancer screening guidelines. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, I.; Lee, A.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Wilson, C. Familial risk for lifestyle-related chronic diseases: Can family health history be used as a motivational tool to promote health behaviour in young adults? Health Promot. J. Aust. 2015, 26, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.M.; Shedlosky-Shoemaker, R.; Atkins, E.; Tworek, C.; Porter, K.U. Improving family history collection. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imes, C.C.; Dougherty, C.M.; Lewis, F.M.; Austin, M.A. Outcomes of a pilot intervention study for young adults at risk for cardiovascular disease based on their family history. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.L.; Beaudoin, C.E.; Sosa, E.T.; Pulczinski, J.C.; Ory, M.G.; McKyer, E.L.J. Motivations, barriers, and behaviors related to obtaining and discussing family health history: A sex-based comparison among young adults. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikoff, R.C.; Costigan, S.A.; Williams, R.L.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Kennedy, S.G.; Robards, S.L.; Allen, J.; Collins, C.E.; Callister, R.; Germov, J. Effectiveness of interventions targeting physical activity, nutrition and healthy weight for university and college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, J. A review of exercise as intervention for sedentary hazardous drinking college students: Rationale and issues. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 58, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.E. Assessment of Dietary Behaviors of College Students Participating in the Health Promotion Program BUCS: Live Well. Ph.D. Thesis, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goergen, A.F.; Ashida, S.; Skapinsky, K.; De Heer, H.D.; Wilkinson, A.V.; Koehly, L.M. What You Don’t Know: Improving Family Health History Knowledge among Multigenerational Families of Mexican Origin. Public Health Genom. 2016, 19, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.P.; Blondin, S.A.; Korn, A.R.; Bakun, P.J.; Tucker, K.L.; Economos, C.D. Behavioral correlates of empirically-derived dietary patterns among university students. Nutrients 2018, 10, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Velez-Argumedo, C.; Gómez, M.I.; Mora, C. College students and eating habits: A study using an ecological model for healthy behavior. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, T.L.; Drumheller, K.; Mallard, J.; McKee, C.; Schlegel, P. Cell phones, text messaging, and facebook: Competing time demands of today’s college students. Coll. Teach. 2010, 59, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, S.; Hsiao, Y.-Y.; Kwok, O.-M.; Tseng, T.-S.; Chen, L.-S. Factors influencing family health history collection among young adults: A structural equation modeling. Genes 2022, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovick, S.R. Understanding family health information seeking: A test of the theory of motivated information management. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauscher, E.A.; Hesse, C. Investigating uncertainty and emotions in conversations about family health history: A test of the theory of motivated information management. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaphingst, K.A.; Lachance, C.R.; Gepp, A.; D’Anna, L.H.; Rios-Ellis, B.U. Educating underserved Latino communities about family health history using lay health advisors. Public Health Genom. 2011, 14, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christianson, C.A.; Powell, K.P.; Hahn, S.E.; Bartz, D.; Roxbury, T.; Blanton, S.H.; Vance, J.M.; Pericak-Vance, M.; Telfair, J.; Henrich, V.C. Findings from a community education needs assessment to facilitate the integration of genomic medicine into primary care. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, A.; Groarke, A. Can risk and illness perceptions predict breast cancer worry in healthy women? J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2052–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussner, K.M.; Jandorf, L.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B. Educational needs about cancer family history and genetic counseling for cancer risk among frontline healthcare clinicians in New York City. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Information National Trends Survey Cycle 1. Available online: https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/Instruments/HINTS5_Cycle1_Annotated_Instrument_English.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Family Health History: The Basics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/famhistory/famhist_basics.htm (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Hoffman, E.W.; Pinkleton, B.E.; Weintraub Austin, E.; Reyes-Velázquez, W. Exploring college students’ use of general and alcohol-related social media and their associations with alcohol-related behaviors. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.J.; Cosby, R.; Boyko, S.; Hatton-Bauer, J.; Turnbull, G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: A systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 26, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Human Genome Research Institute. My Family History Portrait. Available online: http://kahuna.clayton.edu/jqu/FHH/html/index.html (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Amuta, A.O.; Barry, A.E. Influence of family history of cancer on engagement in protective health behaviors. Am. J. Health Educ. 2015, 46, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yeh, Y.L.; Sun, H.; Chang, B.; Chen, L.S. Community-based participatory research: A family health history-based colorectal cancer prevention program among Chinese Americans. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 35, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.W.; Goodson, P.; Goltz, H.H. Exploring genetic numeracy skills in a sample of U.S. university students. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McColl, K.; Debin, M.; Souty, C.; Guerrisi, C.; Turbelin, C.; Falchi, A.; Bonmarin, I.; Paolotti, D.; Obi, C.; Duggan, J.; et al. Are people optimistically biased about the risk of COVID-19 infection? Lessons from the first wave of the pandemic in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. J. Behav. Med. 1982, 5, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.; Ju, I.; Ohs, J.E.; Hinsley, A. Optimistic bias and preventive behavioral engagement in the context of COVID-19. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noar, S.M. Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change in Health and Risk Messaging; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehly, L.M.; Peters, J.A.; Kenen, R.; Hoskins, L.M.; Ersig, A.L.; Kuhn, N.R.; Loud, J.T.; Greene, M.H. Characteristics of health information gatherers, disseminators, and blockers within families at risk of hereditary cancer: Implications for family health communication interventions. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 2203–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashida, S.; Kaphingst, K.A.; Goodman, M.; Schafer, E.J. Family health history communication networks of older adults: Importance of social relationships and disease perceptions. Health Educ. Behav. 2013, 40, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, S.; Bullis, E.; Myers, R.; Zhou, C.J.; Cai, E.M.; Sharma, A.; Bhatia, S.; Orlando, L.A.; Haga, S.B. Awareness of family health history in a predominantly young adult population. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prom-Wormley, E.C.; Clifford, J.S.; Bourdon, J.L.; Barr, P.; Blondino, C.; Ball, K.M.; Montgomery, J.; Davis, J.K.; Real, J.E.; Edwards, A.C.; et al. Developing community-based health education strategies with family history: Assessing the association between community resident family history and interest in health education. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 271, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, S.M. Enhancing cultural considerations in networks and health: A commentary on racial differences in family health history knowledge and interpersonal mechanisms. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, P.; Scheuner, M.T.; Gwinn, M.; Khoury, M.J.; Jorgensen, C. Awareness of family health history as a risk factor for disease. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2004, 53, 1044–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Sundström, C.; Blankers, M.; Khadjesari, Z. Computer-based interventions for problematic alcohol use: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poddar, K.H.; Hosig, K.W.; Anderson, E.S.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M.; Duncan, S.E. Web-based nutrition education intervention improves self-efficacy and self-regulation related to increased dairy intake in college students. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age: Mean (SD 1) | 21.0 (3.4) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 772 (34.0) |

| Female | 1498 (66.0) |

| Birthplace | |

| Born outside of the U.S. | 480 (21.1) |

| Born in the U.S. | 1796 (78.9) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1032 (45.5) |

| Other | 1238 (54.5) |

| Race | |

| African American | 91 (4.0%) |

| Alaska Native or American Indian | 21 (0.9%) |

| White or Caucasian | 1423 (62.7%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 496 (21.9%) |

| Multiple races | 158 (7.0%) |

| Others | 81 (3.6%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/living as married | 138 (6.1) |

| Others | 2138 (93.9) |

| Religion | |

| Christian (including Catholic, Protestant, and all other Christian denominations) | 1462 (64.3) |

| Unaffiliated/none | 528 (23.2) |

| Other | 285 (12.5) |

| Have taken a course in genetics or genomics in college | |

| No | 1921 (84.4) |

| Yes | 355 (15.6) |

| Have taken a course containing genetics/genomics-related information in college | |

| No | 1508 (66.3) |

| Yes | 768 (33.7) |

| Variable | β | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 0.269 | 6.83 | |

| Age (in years) ** | 0.021 | 0.008 | 2.61 |

| Gender (male/female) *** | 0.206 | 0.508 | 4.05 |

| Birthplace (born outside of the U.S./born in the U.S.) | −0.114 | 0.065 | −1.76 |

| Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white/other) * | 0.105 | 0.049 | 2.13 |

| Marital status (married or living as married/others) | −0.059 | 0.109 | −0.54 |

| Have taken a course in genetics or genomics in college (no/yes) | 0.030 | 0.078 | 0.39 |

| Have taken a course containing genetics/genomics-related information in college (no/yes) | 0.114 | 0.059 | 1.94 |

| Fruit consumption | 0.030 | 0.015 | 1.94 |

| Red meat consumption | −0.003 | 0.004 | −0.87 |

| FHH of major diseases in first-degree relatives (no or not sure/yes) * | 0.185 | 0.061 | 3.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Kwok, O.-M.; Ma, P.; Tseng, T.-S.; Chen, L.-S. Are College Students Interested in Family Health History Education? A Large Needs Assessment Survey Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032596

Li M, Kwok O-M, Ma P, Tseng T-S, Chen L-S. Are College Students Interested in Family Health History Education? A Large Needs Assessment Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032596

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ming, Oi-Man Kwok, Ping Ma, Tung-Sung Tseng, and Lei-Shih Chen. 2023. "Are College Students Interested in Family Health History Education? A Large Needs Assessment Survey Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032596

APA StyleLi, M., Kwok, O.-M., Ma, P., Tseng, T.-S., & Chen, L.-S. (2023). Are College Students Interested in Family Health History Education? A Large Needs Assessment Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032596