How Do COVID-19 Vaccine Policies Affect the Young Working Class in the Philippines?

Abstract

1. Background

2. Philippine Context

2.1. Employment Disruption: High Unemployment among the Young Informal Workers

2.2. Two Major Vaccine Policies: Neglecting Young Informal Workers

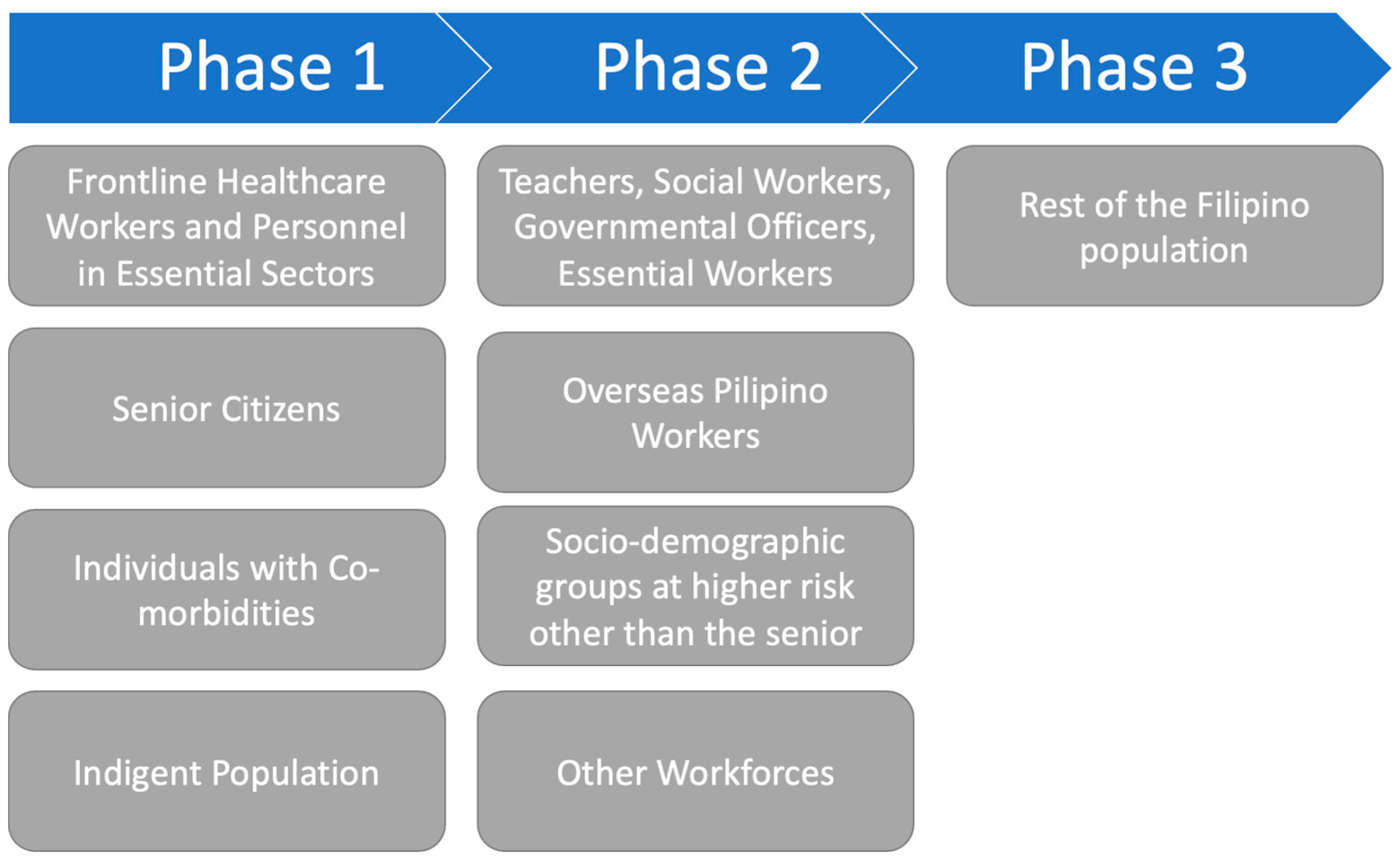

2.2.1. Prioritization Framework

2.2.2. Mandatory Vaccine Policy

3. COVID-19 Vaccine Policies and Inequity: The Unemployed and Unprioritized

4. Outlook: Sink or Swim?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, X.; Joyce, R. Sector Shutdowns During the Coronavirus Crisis: Which Workers Are Most Exposed. Institute for Fiscal Studies. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/538124 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Allam, M.; Ader, M.; Lgrioglu, G. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development Policy Response to Coronavirus. Youth and COVID-19: Response, Recovery and Resilience. 2020. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=134_134356-ud5kox3g26&title=Youth-and-COVID-19-Response-Recovery-and-Resilience (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Gabrijelčič Blenkus, M.; Costongs, C. Intergenerational Inequalities In COVID-19. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, ckab164.296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Saptarshi, M.; et al. A Global Panel Database of Pandemic Policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav 2021, 5, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amit, A.; Pepito, V.; Dayrit, M. Early Response to COVID-19 in the Philippines. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. 2021, 12, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigno, J. Bayanihan to Heal as One Act of 2020 26 Questions: A Primer. Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines Diliman. Available online: https://polisci.upd.edu.ph/resources/bayanihan-primer/ (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Cho, Y.; Johnson, D.; Kawasoe, Y.; Avalos, J.; Rodriquez, R. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Low Income Households in the Philippines: Impending Human Capital Crisis. World Bank, Washington, DC, USA). 2021. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35260 (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- 8. International Labor Organization, Country Office for the Philippines. COVID-19 Labour Market Impact in the Philippines: Assessment and National Policy Responses. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/manila/publications/WCMS_762209/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- National Economic and Development Authority. Report On Labor Force Survey (June 2021). 2021. Available online: https://neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Report-on-LFS-June-2021.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Kabagani, L.J. PH Hits 77% Target Population For COVID-19 Vax Program. Philippine News Agency. 2022. Available online: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1175239 (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Savulescu, J.; Persson, I.; Wilkinson, D. Utilitarianism and the pandemic. Bioethics 2020, 34, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parfit, D. Equality and priority. In Ratio; Blackwell Publisher: Oxford, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of the Philippines Department of Health. Information for Specific Groups. 2021. Available online: https://doh.gov.ph/vaccines/info-for-specific-groups (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Interagency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases. Resolution No. 148-B Series Of 2021. 2021. Available online: https://doh.gov.ph/COVID-19/IATF-Resolutions (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Philippine News Agency. ‘No Vax No Ride’ Policy Lifted By Feb. 1 Under Alert Level 2. 2021. Available online: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1166782 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Marcelo, E. Groups Want IATF’S Mandatory Vaccination Policy Nullified. Philippine Star. 13 May 2022. Availble online: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2022/05/13/2180748/groups-want-iatfs-mandatory-vaccination-policy-nullified (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Giubilini, A. Vaccination Ethics. Br. Med. Bull. 2020, 137, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giubilini, A.; Douglas, T.; Savulescu, J. The Moral Obligation To Be Vaccinated: Utilitarianism, Contractualism, And Collective Easy Rescue. Med. Health Care Philos. 2018, 21, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierik, R. Mandatory Vaccination: An Unqualified Defence. J. Appl. Philos. 2016, 35, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidential Communications Operations Office. More Than 10-M Vaccine Doses Expected in June, As A4 Vaccination Kicks-Off. 2021. Available online: https://mirror.pcoo.gov.ph/OPS-content/more-than-10-m-vaccine-doses-expected-in-june-as-a4-vaccination-kicks-off/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- ASEAN Biodiaspora Virtual Center. COVID-19 Situational Report in the ASEAN Region as of 7 June 2021. 2021. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/COVID-19_Situational-Report_ASEAN-BioDiaspora-Regional-Virtual-Center_7June2021.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Preliminary Results of the 2019 Annual Estimates Of Labor Force Survey (LFS). 2019. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/preliminary-results-2019-annual-estimates-labor-force-survey-lfs (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Unemployment Rate in June 2021 Is Estimated At 7.7 Percent. 2021. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/unemployment-rate-june-2021-estimated-77-percent (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Ortiz, D.; Abrigo, M.; The Triple Burden of Disease. Philippine Institute for Development Studies Economic Issue of the Day 2017, 17. Available online: https://www.pids.gov.ph/publication/economic-issue-of-the-day/the-triple-burden-of-disease (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Bayani, D.; Tan, S. Health Systems Impact of COVID-19 in the Philippines; CGD Working Paper 569; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nemenzo, J. Corona Chronicles: Voices from the Field. Vaccine Inequality in the Philippines: How the Pandemic and Vaccination Schemes have Exacerbated Inequality. 2022. Available online: https://covid-19chronicles.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/post-066-html/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Patag, K.; Royandoyan, R. Balisacan To Return to NEDA as Marcos’ Chief Socioeconomic Planner. Philippine Star. 3 May 2022. Available online: https://www.philstar.com/business/2022/05/23/2181707/balisacan-return-neda-marcos-chief-socioeconomic-planner (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Rivas, R. DOF Urges Marcos: Postpone Income Tax Cuts, Slap New Taxes, Slash VAT Exemptions. Rappler. 5 May 2022. Available online: https://www.rappler.com/business/department-finance-proposals-marcos-jr-new-taxes-slash-vat-exemptions/ (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Inquirer.net. Incoming Finance Chief Ben Diokno Does Not Favor Tax Hikes To Tackle Debt, 2022. 27 May 2022. Available online: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1603362/finance-chief-designate-ben-diokno-does-not-favor-tax-hikes-to-tackle-debt (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Bird, K.; Lozano, C.; Mendoza, T. Philippines’ COVID-19 Employment Challenge: Labor Market Programs to The Rescue. Asian Development Blog. 2022. Available online: https://blogs.adb.org/blog/philippines-covid-19-employment-challenge-labor-market-programs-to-rescue (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Business World. More Cybersecurity Professionals Needed Amid Increased Threats. 2 December 2021. Available online: https://www.bworldonline.com/technology/2021/12/02/414592/more-cybersecurity-professionals-needed-amid-increased-threats/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Gutteres, A. Tackling Inequality: A New Social Contract For A New Era. United Nations: COVID-19 Response. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/tackling-inequality-new-social-contract-new-era (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Department of Health. The New Normal For Health. 2021. Available online: https://doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/The-New-Normal-for-Health.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2022).

| Timeline | Event(s) |

|---|---|

| 30 January 2020 | Index Patient arrives in the Philippines A 30-year-old female Chinese national who visited the country for leisure |

| 7 March 2020 | The first local transmission of COVID-19 was confirmed |

| 9 March 2020 | President Rodrigo Duterte issued Proclamation No. 922, declaring the country under a state of public health emergency |

| 12 March 2020 | Metro Manila was placed under partial lockdown to prevent a nationwide spread of the virus |

| 16 March 2020 | The entire Luzon was put under “enhanced community quarantine” |

| 17 March 2020 | State of Calamity throughout the Philippines and an imposed Enhanced Community Quarantine throughout Luzon |

| 25 March 2020 | Bayanihan Heal as One Act was enacted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estoce, R.H.Y.; Ngan, O.M.Y.; Calderon, P.E.E. How Do COVID-19 Vaccine Policies Affect the Young Working Class in the Philippines? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032593

Estoce RHY, Ngan OMY, Calderon PEE. How Do COVID-19 Vaccine Policies Affect the Young Working Class in the Philippines? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032593

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstoce, Rey Hikaru Y., Olivia M. Y. Ngan, and Pacifico Eric E. Calderon. 2023. "How Do COVID-19 Vaccine Policies Affect the Young Working Class in the Philippines?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032593

APA StyleEstoce, R. H. Y., Ngan, O. M. Y., & Calderon, P. E. E. (2023). How Do COVID-19 Vaccine Policies Affect the Young Working Class in the Philippines? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032593