Stressors, Barriers and Facilitators Faced by Australian Farmers When Transitioning to Retirement: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What stressors do Australian farmers face when considering or transitioning to retirement?

- What barriers and facilitators may hinder or help Australian farmers during this transition?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

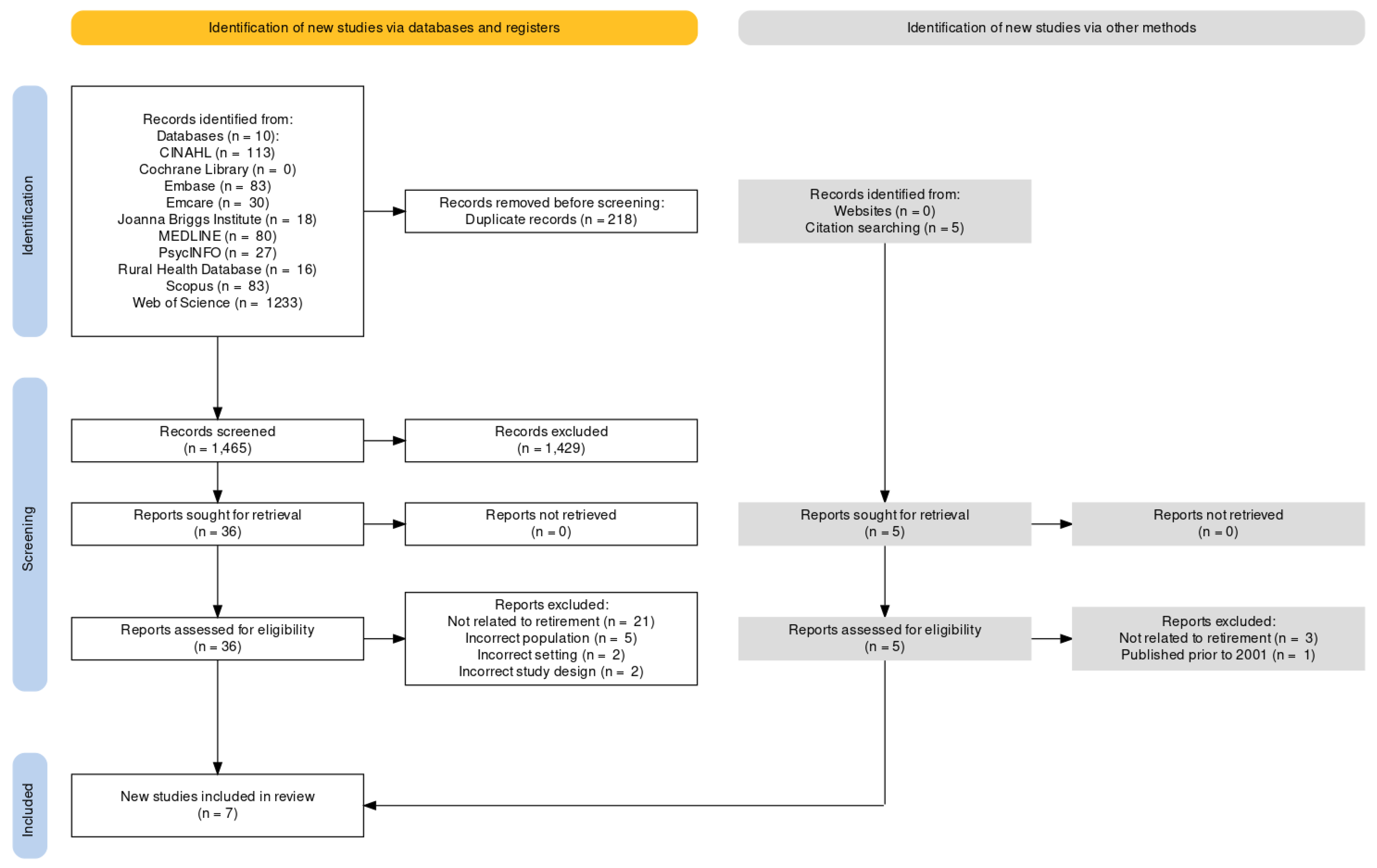

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Participant Characteristics

3.4. Sources of Stress When Transitioning to Retirement

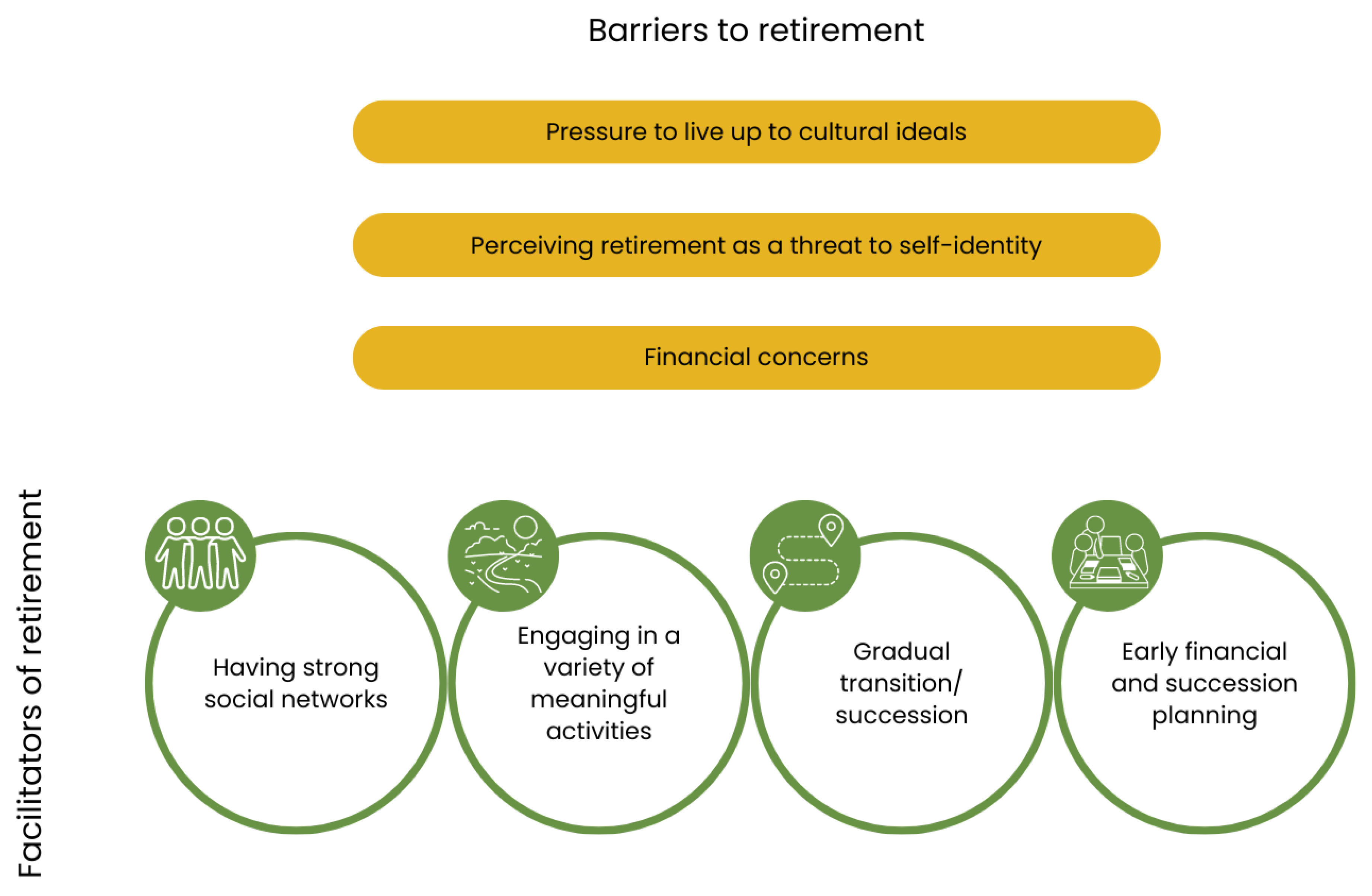

3.5. Barriers to Retirement

3.5.1. Pressure to Live Up to Farming Ideals

3.5.2. Perceiving Retirement as a Threat to Self-Identity

3.5.3. Financial Concerns

3.6. Facilitators of Reitrement

3.6.1. Having Strong Social Networks

3.6.2. Engaging in a Variety of Meaningful Interests and Activities

3.6.3. Gradual Transition/Succession

3.6.4. Early Financial and Succession Planning

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Handley, T.E.; Lewin, T.J.; Butterworth, P.; Kelly, B.J. Employment and retirement impacts on health and wellbeing among a sample of rural Australians. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, A.; Howie, L.; Feldman, S. Retirement: What will you do? A narrative inquiry of occupation-based planning for retirement: Implications for practice. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2010, 57, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagers, J.; Franklin, R.C.; Broome, K.; Yau, M.K. The influence of work on the transition to retirement: A qualitative study. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 81, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H.J.L. Attitudes to work and retirement: Generalization or diversity? Scand J. Occup. Ther. 1999, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retirement and Retirement Intentions, Australia. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/retirement-and-retirement-intentions-australia/latest-release (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing. Available online: https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au/industries/industry-details?industryCode=A (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Downey, H.; Threlkeld, G.; Warburton, J. What is the role of place identity in older farming couples’ retirement considerations? J. Rural Stud. 2017, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, B.; Stenekes, N.; Kruger, H.; Kancans, R. ABARES Insights: Snapshot of Australia’s Agricultural Workforce; Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Forney, J.; Sutherland, L.-A. Identities on the family farm: Agrarianism, materiality and the ‘good farmer’. In Handbook on the Human Impact of Agriculture; James, Jr., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wythes, A.J.; Lyons, M. Leaving the land: An exploratory study of retirement for a small group of Australian men. Rural Remote Health 2006, 6, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, E.; Foskey, R.; Reeve, I. Farm Succession and Inheritance-Comparing Australian and International Trends; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Falkiner, O.; Steen, A.; Hicks, J.; Keogh, D. Current practices in Australian farm succession planning: Surveying the issues. Financ. Plan. Res. J. 2017, 3, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sappey, R.; Hicks, J.; Parikshit, B.; Keogh, D.; Rakesh, G. Succession Planning in Australian Farming. Australas. Acc. Bus. Financ. J. 2012, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, M.; Whittenbury, K. Social impacts of reduced water availability in Australia’s Murray Darling Basin: Adaptation or maladaptation. Int. J. Water 2014, 8, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.; Barr, N.; O’Callaghan, Z.; Brumby, S.; Warburton, J. Healthy ageing: Farming into the twilight. Rural Soc. 2013, 22, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.K.; Handley, T.; Kiem, A.S.; Rich, J.L.; Lewin, T.J.; Askland, H.H.; Askarimarnani, S.S.; Perkins, D.A.; Kelly, B.J. Drought-related stress among farmers: Findings from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorthouse, M.; Stone, L. Inequity amplified: Climate change, the Australian farmer, and mental health. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, H.G.; Threlkeld, G.; Warburton, J. How do older Australian farming couples construct generativity across the life course?: A narrative exploration. J. Aging Stud. 2016, 38, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, N. The House on the Hill: The Transformation of Australia’s Farming Communities; Halstead Press: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, P. It’s about people: Changing perspective. In A Report to Government by an Expert Social Panel on Dryness; Drought Policy Review Expert Social Panel: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Winterton, R.; Warburton, J. Ageing in the bush: The role of rural places in maintaining identity for long term rural residents and retirement migrants in north-east Victoria, Australia. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M. Still being the ‘good farmer’: (Non-)retirement and the preservation of farming identities in older age. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnham, B.; Bryant, L. Problematising the suicides of older male farmers: Subjective, social and cultural considerations. Sociol. Rural. 2014, 54, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.; Fragar, L.; Pollock, K. Health and Safety of Older Farmers in Australia—The Facts; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Farmsafe Australia. Safer Farms 2021: Agricultural Injury and Fatality-Trend Report; Farmsafe Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brumby, S.; Chandrasekara, A.; McCoombe, S.; Kremer, P.; Lewandowski, P. Farming fit? Dispelling the Australian agrarian myth. BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumby, S.; Chandrasekara, A.; Kremer, P.; Torres, S.; McCoombe, S.; Lewandowski, P. The effect of physical activity on psychological distress, cortisol and obesity: Results of the farming fit intervention program. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, M. Rural male suicide in Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnek-Georgeson, K.T.; Wilson, L.A.; Page, A. Factors influencing suicide in older rural males: A review of Australian studies. Rural Remote Health 2017, 17, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterton, R.; Warburton, J. Does place matter? Reviewing the experience of disadvantage for older people in rural Australia. Rural Soc. 2011, 20, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, C. Aged care in rural Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2021, 29, 483–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackberry, I.; Wilding, C.; Chisholm, M.; Wishart, D.; Keeton, W.; Chan, C.; Fraser, M.; Boak, J.; Knight, K.; Horsfall, L. Empowering Older People in Accessing Aged Care Services in a Consumer Market; John Richards Centre for Rural Ageing Research, La Trobe University: Wodonga, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vayro, C.; Brownlow, C.; Ireland, M.; March, S. ‘Farming is not just an occupation [but] a whole lifestyle’: A qualitative examination of lifestyle and cultural factors affecting mental health help-seeking in Australian farmers. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, Z.; Warburton, J. No one to fill my shoes: Narrative practices of three ageing Australian male farmers. Ageing Soc. 2017, 37, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifer, J.; Thompson, A.P. Subjective realities of older male farmers: Self-perceptions of ageing and work. Rural Soc. 2006, 16, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; 2020 Version; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 12 Farmers and Farm Managers. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/classifications/anzsco-australian-and-new-zealand-standard-classification-occupations/2022/browse-classification/1/12 (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Littlewood, A.; Marshall, C.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Rader, T.; Shokraneh, F.; Thomas, J.; et al. Technical Supplement to Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Cochrane: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, L.; Whiteford, G. Understanding occupational transitions: A study of older rural men’s retirement experiences. J. Occup. Sci. 2009, 16, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foskey, R. Older Farmers and Retirement; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society; W W Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, K.M.; Kettler, L.J.; Skaczkowski, G.; Turnbull, D.A. Farmers’ stress and coping in a time of drought. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Larder, N. Good farming as surviving well in rural Australia. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, K.M.; Hull, M.; Jones, M.; Dollman, J. A comparison of barriers to accessing services for mental and physical health conditions in a sample of rural Australian adults. Rural Remote Health 2018, 18, 4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, M.J.; Gunn, K.M.; Smith, A.E.; Jones, M.; Dollman, J. “We’re lucky to have doctors at all”; A qualitative exploration of Australian farmers’ barriers and facilitators to health-related help-seeking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, M.J.; Fennel, K.M.; Vallury, K.; Jones, M.; Dollman, J. A comparison of barriers to mental health support-seeking among farming and non-farming adults in rural South Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2017, 25, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, K.M.; Martin, K.; Wilson, C.J.; Trenerry, C.; Sharplin, G.; Dollman, J. Barriers to seeking help for skin cancer detection in rural Australia. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, K.M.; Turnbull, D.A.; Dollman, J.; Kettler, L.; Bamford, L.; Vincent, A.D. Why are some drought-affected farmers less distressed than others? The association between stress, psychological distress, acceptance, behavioural disengagement and neuroticism. Aust. J. Rural Health 2021, 29, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, R.; Alabakis, J.; Bowles, K.-A.; Smith, K. Suicide Prevention in High-Risk Occupations: An Evidence Check Rapid Review Brokered by the Sax Institute for the NSW Ministry of Health. 2020. Available online: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Lobley, M.; Baker, J.R.; Whitehead, I. Farm succession and retirement: Some international comparisons. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2010, 1, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contzen, S.; Zbinden, K.; Neuenschwander, C.; Métrailler, M. Retirement as a discrete life-stage of farming men and women’s biography? Sociol. Rural. 2017, 57, 730–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, S.F.; Farrell, M.; McDonagh, J.; Kinsella, A. ‘Farmers don’t retire’: Re-evaluating how we engage with and understand the ‘older’ farmer’s perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, S.F.; McDonagh, J.; Farrell, M.; Kinsella, A. Till death do us part: Exploring the Irish farmer-farm relationship in later life through the lens of ‘Insideness’. Int. Farm Manag. Assoc. Inst. Agric. Manag. 2018, 7, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, M. ‘Moving on’? Exploring the geographies of retirement adjustment amongst farming couples. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2012, 13, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, A.; McKenzie, F.H. Revisiting Missed Opportunities–Growing Women’s Contribution to Agriculture; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, M. Women in agriculture: The ‘new entrepreneurs’. Aust. Fem. Stud. 2003, 18, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancian, F.M.; Oliker, S.J. Caring and Gender; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J.; Groves, D. (Eds.) A Labour of Love: Women, Work and Caring; Routledge: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences. ABARES Insights: Snapshot of Australian Agriculture 2022; Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences: Canberra, Australia, 2022.

| Author | Aim | Study Design | Methods | Sample Size | Participant Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downey et. al. [7] | To examine the role of place identity in older farming couples’ retirement considerations. | Social constructivist narrative inquiry | 60–90-min semi-structured interviews with couples | N = 6 couples |

|

| Downey et. al. [18] | To explore how older farming couples construct generativity throughout the life course. | Narrative study | 60–90-min semi-structured, interviews with couples | N = 6 couples |

|

| Foskey [41] | To understand how farmers define and experience retirement and ageing and the factors likely to influence their retirement actions. | Government report, involving literature review, mixed methods study and development, pilot and evaluation of peer support program | Literature review, individual semi-structured interviews, short survey, focus groups, follow-up focus group | N = 71 (service providers, n = 11; active and retired farmers, n = 60) N = 9 retired and semi-retired farmers participated in peer support program |

|

| O’Callaghan & Warburton [34] | To examine the impact of ageing and possible loss of the family farm on how farmers construct their situations and their self-identity. | Narrative ethnographic study | Individual interviews, observation, follow-up interview | N = 3 |

|

| Rogers et. al. [15] | To report on the outcomes of a policy and research forum on the demographic, economic, cultural, identity and health dimensions of ageing farmers. | Report on forum | Report on forum about ‘ageing farmers’, including summary of keynote presentations from three researchers and panel discussion with policymakers and rural service providers | - |

|

| Wiseman & Whiteford [40] | To report findings from a life history study exploring the retirement experiences of rural men. | Qualitative interpretivist study | Focus group, 60–90-min individual interviews | N = 8 |

|

| Wythes & Lyons [10] | To explore the retirement experiences of rural men who have left the land. | Phenomenological study | 60–90-min semi-structured, individual interviews | N = 7 |

|

| Main Theme | Subtheme | Examples from Included Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure to live up to farming ideals | Family farming continuity | |

| Independence |

| |

| Productivity |

| |

| Rural masculinity and stoicism |

| |

| Perceiving retirement as a threat to self-identity | Neglected social networks |

|

| Connection to place and work |

| |

| Underdeveloped interests and activities external to farming |

| |

| Connotations of retirement as end of life |

| |

| Financial concerns | Debt burden | |

| Selling the farm | ||

| Access to Government Age Pension |

|

| Main Theme | Subtheme | Examples from Included Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Having strong social networks | Family networks |

|

| Involvement in community |

| |

| Industry networks |

| |

| New friendships in retirement |

| |

| Engaging in a variety of meaningful interests and activities | Continuity of farming interests and meaningful external interests and activities |

|

| Planning a lifestyle beyond farming |

| |

| Gradual transition/succession | Winding down personal farming tasks |

|

| Downsizing the farm over time | ||

| Handing over management to the next generation over time |

| |

| Early financial and succession planning | Preparing for retirement throughout farming career |

|

| Involving family in retirement planning |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fletcher, C.M.E.; Stewart, L.; Gunn, K.M. Stressors, Barriers and Facilitators Faced by Australian Farmers When Transitioning to Retirement: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032588

Fletcher CME, Stewart L, Gunn KM. Stressors, Barriers and Facilitators Faced by Australian Farmers When Transitioning to Retirement: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032588

Chicago/Turabian StyleFletcher, Chloe M. E., Louise Stewart, and Kate M. Gunn. 2023. "Stressors, Barriers and Facilitators Faced by Australian Farmers When Transitioning to Retirement: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032588

APA StyleFletcher, C. M. E., Stewart, L., & Gunn, K. M. (2023). Stressors, Barriers and Facilitators Faced by Australian Farmers When Transitioning to Retirement: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032588